Abstract

Dysnatremia is common in donors and recipients of liver transplantation (LT). However, the influence of dysnatremia on LT prognosis remains controversial. This study aimed to investigate effects of donors’ and recipients’ serum sodium on LT prognosis. We retrospectively reviewed 248 recipients who underwent orthotopic LT at our center between January 2016 and December 2018. Donors and recipients perioperative and 3-year postoperative clinical data were included. Delta serum sodium was defined as the donors’ serum sodium minus the paired recipients’ serum sodium. Donors with serum sodium > 145 mmol/L had significantly higher preoperative blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (P < 0.01) and creatinine (Cr) (P < 0.01) than others. Preoperative total bilirubin (TBIL) (P < 0.01), direct bilirubin (DBIL) (P < 0.01), BUN (P < 0.01), Cr (P < 0.01) were significantly higher in the hyponatremia group of recipients than the other groups, but both of donors’ and recipients’ serum sodium had no effect on the LT prognosis. In the delta serum sodium < 0 mmol/L group, TBIL (P < 0.01) and DBIL (P < 0.01) were significantly higher in postoperative 1 week than the other groups, but delta serum sodium had no effect on the postoperative survival rates. Dysnatremia in donors and recipients of LT have no effect on postoperative survival rates, hepatic and renal function, but recipients with higher serum sodium than donors have significantly higher TBIL and DBIL at 1 week postoperatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Donors shortage limits LT, and using marginal donor livers can expand the donors pool 1. Hypernatremia donors are one kind of marginal donors2, donors’ hypernatremia is mainly associated with increased secretion of antidiuretic hormone and excessive infusion of fluids containing sodium3,4. The effect of donors’ hypernatremia on LT prognosis remains controversial. Some studies have reported that hypernatremia in donors leads to hepatic dysfunction in early postoperative period5,6,7, possibly mechanism is that hypernatremia leads to dehydration of donor hepatocytes, the osmotic pressure of hepatocytes suddenly decreases when donor livers are transplanted into recipients, which terminally leads to hepatocytes swelling and increased ischemia–reperfusion injury7. However, other studies have reported that hypernatremia has no effect on postoperative hepatic function8,9,10.

Dysnatremia is also common in recipients of LT. The universally used diagnostic criterion for hypernatremia in recipients is serum sodium > 145 mmol/L, hyponatremia is serum sodium < 135 mmol/L11,12. Recipients on the waiting list often have hyponatremia due to preoperative hypoproteinaemia, diuretic use, and renal insufficiency13,14. It has been widely reported that recipients’ hyponatremia has a negative impact on postoperative survival rates and increases postoperative neurological complications15. It is contradictory that some researches showed neither hyponatremia nor hypernatremia in recipients affects the postoperative 90-day survival rates16, correcting serum sodium by ≥ 8 mEq/L in 24 h significantly increases the risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome15,17.

We speculated that variation of serum sodium between donors and recipients causes a change in the osmotic pressure to which the hepatocytes are exposed, which may have an impact on the prognosis of LT. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of serum sodium in donors and recipients on the prognosis of LT.

Materials and methods

Study population

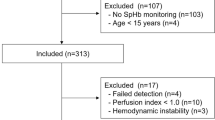

Between January 2016 and December 2018, a total of 259 recipients underwent orthotopic LT at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, 10 pediatric donors and one pediatric recipient were excluded, finally 248 recipients were included in the study, and the follow-up period of this study was 3 years. Consent was obtained from the donors’ relatives for organ donation in all cases. Because the study was retrospective and noninterventional, the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Data collection

Donors’ preoperative clinical data and recipients’ perioperative and postoperative 3-year clinical data were collected. Donors’ serum sodium was defined as the last serum sodium before organ acquisition, 28 donors lacked preoperative serum sodium, and recipients’ serum sodium was defined as the last serum sodium before LT. Preoperative donors’ data included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), cause of death, serum sodium, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), TBIL, DBIL, Cr, and BUN. Recipients’ preoperative data included age, sex, primary disease, Child–Pugh score, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, MELD-Na score, ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, Cr, and BUN, albumin (ALB), international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). Intraoperative data included cold ischemia time (CIT), warm ischemia time (WIT), anhepatic phase, blood loss, urine volume, red blood cell (RBC) count and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion volume. Postoperative data included length of hospital stays, ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, Cr, and BUN, postoperative recipient survival rates at 1 week, 1 month, 1 year, and 3 years.

Immunosuppressive protocol

The induction regimen was intravenous injection methylprednisolone 5 mg/kg and baliximab 20 mg on intraoperative period and postoperative day 4. The immunosuppressive regimen included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids. Oral tacrolimus 0.06–0.08 mg/kg/d was started 48 h postoperatively in two oral doses to maintain the blood tacrolimus concentrations < 5 μg/L without increasing rejection, sirolimus or mycophenolate mofetil was added if the hepatic function became abnormal, glucocorticoids were generally discontinued approximately one week postoperatively.

Analysis of outcomes

Donors and recipients were classified according to their serum sodium. Serum sodium > 145 mmol/L was defined as hypernatremia, serum sodium < 135 mmol/L and 135–145 mmol/L were defined as hyponatremia and normonatremia, respectively. Delta serum sodium was calculated by subtracting the recipient’s serum sodium from the donors’ serum sodium, and recipients were divided into three groups according to delta serum sodium (< 0 mmol/L, 0–10 mmol/L, > 10 mmol/L). We evaluated the relationship between donors’ serum sodium and donors’ preoperative health status, the relationship between recipients’ serum sodium and recipients’ preoperative health status, effects of donors’, recipients’, and delta serum sodium on intraoperative and postoperative outcomes of LT.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages, analyzed using the chi-squared test and fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables according to their distribution were expressed as the mean (standard error) or median (interquartile range) and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, LSD-t test, or Kruskal–Wallis test. Kaplan‒Meier curves were used to estimate the postoperative survival rates, the log-rank test was used to analyze the differences in the curves. Statistical significance was defined as P less than 0.05 in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 27.0.1.

Results

Preoperative characteristics of donors

There were 26 patients with hyponatremia, 104 patients with normonatremia and 90 patients with hypernatremia in donors, respectively. The BUN (P < 0.01) and Cr (P < 0.01) were significantly different in three groups, the BUN was 9.23 ± 0.65 mmoI/L and Cr was 129.57 ± 9.99 μmol/L in hypernatremia group, which were higher than those in the other groups. Age, gender, BMI, cause of death, ALT, AST, ALB, PT, INR, TBIL, and DBIL in the donor groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Perioperative characteristics of recipients

There were 176 recipients with normonatremia, 55 recipients with hyponatremia and 17 recipients with hypernatremia, respectively. In hyponatremia group, preoperative TBIL was 238.94 ± 28.13 μmol/L (P < 0.01), DBIL was 158.23 ± 20.34 μmol/L (P < 0.01), BUN was 8.25 ± 0.72 mmoI/L (P < 0.01), and Cr was 84.04 ± 5.17 μmoI/L (P < 0.01), all of them were significantly higher than those in the hypernatremia and normonatremia groups. Hence, the MELD scores (P < 0.01) and MELD-Na scores (P < 0.01) were significantly higher in the hyponatremia group. There was no significant difference in terms of age, gender, BMI, disease, ALT, AST, ALB, PT, and INR in the recipients (Table 2). The overall 1-year survival rate of recipients was 87.9%, the 2-year and 3-year survival rates were 82.2% and 80.9%, respectively.

Effects of donors’ serum sodium on prognosis

There was no significant difference in CIT, WIT and intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative transfusion and urine volume, postoperative hospital stays, or postoperative hepatic and renal function (Table S1). The survival rates within 3 years of the recipients classified according to donors’ serum sodium has no remarkable difference (P = 0.37) (Fig. 1).

Effects of recipients’ serum sodium on prognosis

Intraoperative blood loss was 1220.09 ± 226.04 ml in the hyponatremia group, which was higher than that in the other groups, but didn’t have significant difference (P = 0.26). Transfusion volume of RBC (P < 0.01) was 5.31 ± 0.80 U in hyponatremia group, which was higher than the other groups. There was no significant difference in intraoperative urine volume, hospital stay, survival rates within postoperative 3 years (P = 0.40) (Fig. 2), postoperative hepatic and renal function in the recipients classified by recipients’ preoperative serum sodium (Table S2).

Effects of delta serum sodium on prognosis

We divided the recipients into three groups according to delta serum sodium: 69 patients with delta sodium < 0 mmol/L, 70 patients with delta sodium 0–10 mmol/L, and 81 patients with delta sodium > 10 mmol/L. TBIL at 1 week postoperatively was significantly higher in the delta sodium < 0 mmol/L group (81.67 ± 10.54 μmol/L) than that in the other two groups (43.14 ± 4.55 μmol/L, 63.40 ± 7.49 μmol/L) (P < 0.01). Similarly, DBIL at 1 week postoperatively was observably higher in the delta sodium < 0 mmol/L group (60.71 ± 7.61 μmol/L) than that in the other two groups (31.87 ± 3.82 μmol/L, 49.35 ± 6.22 μmol/L) (P < 0.01). There was no difference in intraoperative urine volume, blood loss, postoperative renal function (Table 3), postoperative coagulation indicators, or survival rates within 3 years postoperatively among the three groups (P = 0.58) (Fig. 3).

Pairwise comparisons between the delta sodium groups showed that TBIL (P < 0.01) and DBIL (P < 0.01) at 1 week postoperatively were markedly different between the delta sodium < 0 mmol/L group and the 0–10 mmol/L group, but the delta sodium > 10 mmol/L group has no obvious different from the other groups (Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that dysnatremia in donors and recipients of LT have no effect on postoperative survival rates, hepatic and renal function, but recipients with higher serum sodium than donors have significantly higher TBIL and DBIL at 1 week postoperatively.

A systematic review including 25 cohort studies of 19,389 patients indicated that donor dysnatremia was related to liver graft dysfunction in the postoperative early stage, but not to recipients’ survival7. However, a study that included 212 patients showed that donors’ hypernatremia was a poor prognostic factor for LT survival rates in donors aged ≥ 70 years18. The prognostic impact of donor hypernatremia was related to the duration of elevated serum sodium, with no effect on postoperative 1-year survival rates of graft and recipient when the duration was < 36 h, but with a significant adverse effect on prognosis when the duration was ≥ 36 h8. Our finding that donor serum sodium had no effect on the prognosis of LT was consistent with the results of some previous clinical studies8,10. Inconsistent criteria for defining hypernatremia may account for the differences of the results. The immunosuppressive regimen after LT plays an important role in preventing postoperative rejection, both too little and too much anti-rejection drugs been used can lead to abnormal liver function. At present, the immunosuppressive regimen of each transplantation center is different, our center's immunosuppressive regimen is described in detail in the method section. However, we are not sure that our regimen is better than others, but we think it may be one of the reasons for the differences in the results of the study.

Approximately 22% of patients with cirrhosis develop to hyponatremia, which mainly due to dilutional hyponatremia, and then hypoproteinaemia and inappropriate diuretic administration17,19. Hyponatremia is an independent risk factor for death in patients on the LT waiting list11, the MELD-Na score, after adding serum sodium to the MELD score, can better predict the risk of death in recipients waiting for transplantation14,20. Our study showed that preoperative hyponatremia in recipients was associated with preoperative poor hepatic and renal function, but didn’t have effect on the prognosis, which is consistent with the findings of many studies21. However, some studies have also reported that elevated preoperative serum sodium increases mortality in recipients awaiting LT22, and hypernatremia is associated with preoperative renal insufficiency23. The inconsistent criteria for the classification of serum sodium and the different duration of abnormal serum sodium may be part of the reasons for the differences in research results.

Many studies have reported that preoperative donors’ hypernatremia has adverse effects on postoperative hepatic function, and similarly, preoperative recipients’ hyponatremia is one of the factors indicating poor prognosis. Therefore, we speculated that transplantation of hypernatremia donor livers to hyponatremia recipients may have more adverse effects on prognosis, however, the results were contrary to our speculation. In this study, we analyzed the effect of delta serum sodium on LT for the first time by combining preoperative donors’ and recipients’ serum sodium, found that transplantation of donor livers to recipients with higher serum sodium had significantly higher TBIL and DBIL at 1 week postoperatively, but delta serum sodium had no effect on long-term prognosis. A study including 54,311 LT patients showed that preoperative hypernatremia in the recipients resulted in significantly decreased patient and graft survival rates at postoperative 90 days, whereas preoperative hyponatremia in the recipients had no effect on postoperative patient or graft survival12, which was related to our findings that increased serum sodium after LT produced an adverse prognosis. A further pairwise comparison of TBIL and DBIL at 1 week postoperatively between the delta sodium groups showed that the < 0 mmol/L group and the 0–10 mmol/L group showed significant differences. Although TBIL and DBIL in the delta sodium > 10 mmol/L group were not significantly different from those in the other groups, the mean values were higher than those in the 0–10 mmol/L group, which may because the large difference in serum sodium between donors and recipients can also have an adverse effect on postoperative hepatic function.

The mechanism of elevated serum sodium leading to impaired liver function has not been reported. A possible molecular mechanism is increased serum sodium aggravates hepatic inflammation and apoptosis, it has been found that elevated serum sodium can activate epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs), which promote to sodium enter into cells24,25,26. Compared with rats fed with normal water, rats fed with high sodium water had more severe renal ischemia–reperfusion injury, and the expression of ENaCs in kidney was significantly higher. The application of ENaCs inhibitor, amiloride, could effectively reduce the renal injury aggravated by hypernatremia25. In cystic fibrosis, excessive activation of ENaCs leads to an increase of intracellular sodium in airway epithelial cells, which in turn elevates the levels of NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-18, and IL-1β, and aggravates airway inflammation24. Hypernatremia promotes the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β in vascular endothelial cells, leading to hypertension and cardiovascular disease, and its effect is achieved by activating ENaCs and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX)26. NCX is a channel that mediates the exchange of calcium and sodium in cell membrane, after cardiac ischemia–reperfusion, the expression of NCX in cardiomyocytes was significantly increased, and the application of NCX inhibitors could observably reduce cardiac ischemia–reperfusion injury27. The possible mechanism is that when the liver is transplanted to a recipient with higher serum sodium than the donor, the concentration of sodium in the environment of hepatic cells is increased, resulting in the activation of ENaCs, and extracellular sodium entering the cells through ENaCs is elevated. The elevated intracellular sodium will increase intracellular calcium through NCX, intracellular calcium overload will activate apoptotic and inflammatory signaling pathways, resulting in aggravated hepatic inflammation and increased hepatocytes death.

At the same time, the increase of extracellular sodium may enter the cell through other sodium channels, such as sodium-hydrogen exchanger-128 and sodium-glucose cotransporter-229, resulting in the increase of intracellular sodium. Sodium is of great significance for maintaining cell morphology and material exchange30,31, the increase of intracellular sodium will lead to imbalance of ion homeostasis and cell metabolic disorders, which may be one of the mechanisms of aggravated liver damage.

As this was a single-center study, the number of included cases was limited, which may lead to bias. This study did not further research postoperative complications, which may need to be improved. There are no international unified classification criteria for donors’ and recipients’ serum sodium, which may lead to confusion to some extent. This study on delta serum sodium of paired donors and recipients is suggestive, and further studies on delta serum sodium in large samples are needed.

In conclusion, this study indicated that recipients whose serum sodium concentration is higher than the donors have significantly elevated TBIL and DBIL in the early postoperative period, which may provide some guidance on how donor livers should be allocated.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. For further inquiries can contact the corresponding author by fccguowz@zzu.edu.cn.

References

Sousa Da Silva, R. X., Weber, A., Dutkowski, P. & Clavien, P. A. Machine perfusion in liver transplantation. Hepatology 76, 1531–1549. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32546 (2022).

Cywinski, J. B. et al. Association between donor-recipient serum sodium differences and orthotopic liver transplant graft function. Liver Transpl. 14, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.21305 (2008).

Seay, N. W., Lehrich, R. W. & Greenberg, A. Diagnosis and management of disorders of body tonicity-hyponatremia and hypernatremia: Core curriculum 2020. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75, 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.014 (2020).

Bernardi, M. & Zaccherini, G. Approach and management of dysnatremias in cirrhosis. Hepatol. Int. 12, 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-018-9894-6 (2018).

Bastos-Neves, D., Salvalaggio, P. R. O. & Almeida, M. D. Risk factors, surgical complications and graft survival in liver transplant recipients with early allograft dysfunction. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 18, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.02.005 (2019).

Leise, M. D. et al. Effect of the pretransplant serum sodium concentration on outcomes following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 20, 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23860 (2014).

Basmaji, J., Hornby, L., Rochwerg, B., Luke, P. & Ball, I. M. Impact of donor sodium levels on clinical outcomes in liver transplant recipients: A systematic review. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 32, 1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001776 (2020).

Zhou, Z. J. et al. Prognostic factors influencing outcome in adult liver transplantation using hypernatremic organ donation after brain death. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 19, 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbpd.2020.06.003 (2020).

Mangus, R. S. et al. Severe hypernatremia in deceased liver donors does not impact early transplant outcome. Transplantation 90, 438–443. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e764c0 (2010).

Kaseje, N., McLin, V., Toso, C., Poncet, A. & Wildhaber, B. E. Donor hypernatremia before procurement and early outcomes following pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 21, 1076–1081. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.24145 (2015).

Nagai, S. et al. Effects of allocating livers for transplantation based on model for end-stage liver disease-sodium scores on patient outcomes. Gastroenterology 155, 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.025 (2018).

McDonald, M. F. et al. Elevated serum sodium in recipients of liver transplantation has a substantial impact on outcomes. Transpl. Int. 34, 1971–1983. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.13968 (2021).

Rondon-Berrios, H. & Velez, J. C. Q. Hyponatremia in cirrhosis. Clin. Liver. Dis. 26, 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2022.01.001 (2022).

Goudsmit, B. F. J. et al. Validation of the model for end-stage liver disease sodium (MELD-Na) score in the Eurotransplant region. Am. J. Transplant 21, 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16142 (2021).

Berry, K., Copeland, T., Ku, E. & Lai, J. C. Perioperative delta sodium and post-liver transplant neurological complications in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 106, 1609–1614. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000004102 (2022).

Mihaylov, P. et al. Prognostic impact of peritransplant serum sodium concentrations in liver transplantation. Ann Transplant 24, 418–425. https://doi.org/10.12659/AOT.914951 (2019).

Leise, M. & Cardenas, A. Hyponatremia in cirrhosis: Implications for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 24, 1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25327 (2018).

Caso-Maestro, O. et al. Analyzing predictors of graft survival in patients undergoing liver transplantation with donors aged 70 years and over. World J. Gastroenterol. 24, 5391–5402. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5391 (2018).

Adrogue, H. J., Tucker, B. M. & Madias, N. E. Diagnosis and management of hyponatremia: A review. JAMA 328, 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.11176 (2022).

Ruf, A. E. et al. Addition of serum sodium into the MELD score predicts waiting list mortality better than MELD alone. Liver Transpl. 11, 336–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20329 (2005).

Bossen, L., Gines, P., Vilstrup, H., Watson, H. & Jepsen, P. Serum sodium as a risk factor for hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34, 914–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14558 (2019).

Rana, A. et al. No child left behind: Liver transplantation in critically Ill children. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 224, 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.025 (2017).

van IJzendoorn, M. et al. Renal function is a major determinant of ICU-acquired hypernatremia: A balance study on sodium handling. J. Transl. Int. Med. 8, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.2478/jtim-2020-0026 (2020).

Scambler, T. et al. ENaC-mediated sodium influx exacerbates NLRP3-dependent inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Elife 8, E49248. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49248 (2019).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Upregulation of mineralocorticoid receptor contributes to development of salt-sensitive hypertension after ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147831 (2022).

Pitzer, A. et al. DC ENaC-dependent inflammasome activation contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension. Circ. Res. 131, 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.320818 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Kdm6A protects against hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via H3K27me3 demethylation of Ncx gene. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 12, 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-019-09882-5 (2019).

Kang, B. S. et al. An inhibitor of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger-1 (NHE-1), amiloride, reduced zinc accumulation and hippocampal neuronal death after ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124232 (2020).

Yu, Y. W. et al. Sodium-glucose Co-transporter-2 inhibitor of dapagliflozin attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by limiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and modulating autophagy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 768214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.768214 (2021).

Jiang, D. et al. Structure of the cardiac sodium channel. Cell 180, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.041 (2020).

Han, X. et al. Mechanism analysis of toxicity of sodium sulfite to human hepatocytes L02. Mol. Cell Biochem. 473, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03805-8 (2020).

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (82170648, 81971881, 82170670), Leading Talents of Zhongyuan Science and Technology Innovation (214200510027), Medical Science and Technology Program of Henan Province (SB201901045), Funding for Scientific Research and Innovation Team of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (ZYCXTD2023007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the idea and designed the study (W.G.), data collection and analysis (Y.C., H.L., M.Z., Z.W., H.F.), manuscript writing and revision (P.W., J.Z.), manuscript grammar revision (Y.C.). All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Ref: 2023-KY-0006), and this study was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Li, H., Zhang, M. et al. Effects of donors’ and recipients’ preoperative serum sodium on the prognosis of liver transplantation. Sci Rep 14, 20304 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71218-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71218-4