Abstract

Brachial artery access for coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures is associated with a greater risk of vascular complications. To determine whether 3D printing of a novel elbow joint fixation device could reduce postoperative complications after percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures through the brachial artery. Patients who underwent percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures by brachial access were randomly assigned to receive either a 3D-printed elbow joint fixation device (brace group) or traditional compression (control group) from March 2023 to December 2023. The severity of puncture site-related discomfort at 24 h postsurgery was significantly lower in the brace group (P = 0.014). Similarly, the upper arm calibration rate at 24 h postsurgery was significantly lower in the brace group [0.024 (0.019–0.046) vs. 0.077 (0.038–0.103), P < 0.001], as was the forearm calibration rate [0.026 (0.024–0.049) vs. 0.050 (0.023–0.091), P = 0.007]. The brace group had a significantly lower area of subcutaneous hemorrhage at 24 h postsurgery [0.255 (0–1.00) vs. 1 (0.25–1.75) cm2]. In patients who underwent percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures by brachial access after manual compression hemostasis, the novel elbow joint fixation device was effective at reducing puncture site-related discomfort, alleviating the degree of swelling, and minimizing the subcutaneous bleeding area. Additionally, no significant complications were observed.

Trial registration: China Clinical Trial Registration on 01/03/2023 (ChiCTR2300068791).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinically, radial access is the preferred puncture approach for percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures due to its low risk of bleeding and vascular-related complications1. However, the radial artery can lead to puncture failure due to vasospasm, hypoplasia, occlusion or anatomical variation2,3. At present, the femoral approach is a common alternative for removing radial artery puncture failure, but when there are contraindications or when the patient refuses, brachial access plays an essential role in percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures3,4. The first percutaneous coronary diagnostic procedure in the world was performed via brachial access5. Transbrachial artery puncture has a higher success rate than does femoral access due to its larger vessel diameter, shorter compression time postsurgery, and lower rate of postoperative complications6.

However, there are several puncture site-related complications, such as local hematomas, moderate to severe pain, brachial thrombosis, limb ischemia, and increased postoperative compression time7. At present, traditional manual compression (MC) is still the simplest and most commonly used hemostasis method after artery puncture and is regarded as the gold standard8,9. However, after manual hemostasis is established, gauze is used to wrap and fix the arm. This method cannot effectively restrict arm movement, leading to an increased risk of subsequent complications9. Additionally, there is still high puncture site-related discomfort, which is due to the lack of effective solutions.

Puncture site-related discomfort is related mainly to passive compression, ineffective compression, and other factors. 3D printing technology is on the rise, and it has characteristics that are more in line with the physiological structure of patients. Theoretically, a 3D-printed external fixation brace can better fit the patient’s elbow joint and enable effective immobilization, thereby reducing the discomfort associated with the puncture point10,11,12. Although previous studies have suggested that 3D printing, an emerging technology, can be used to reduce complications during brachial artery puncture, there is currently a lack of relevant research confirming its effectiveness.

The objective of this randomized controlled trial was to investigate whether the application of a 3D-printed elbow external fixation device combined with manual compression provides superior outcomes compared to simple manual compression in alleviating discomfort and preventing vascular complications following brachial artery puncture for percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. We posited that these devices would improve patient comfort and reduce brachial artery puncture complications.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Deyang People’s Hospital on January 16, 2023 (No. 2021–04-099-K01), this study was registered with the China Clinical Trial Registration on 01/03/2023 (ChiCTR2300068791). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participation.

The inclusion criteria were age > 18 years; underwent percutaneous coronary diagnostic (coronary angiography) or therapeutic procedures (percutaneous coronary intervention) via brachial artery access (with radial artery puncture failure because of vasospasm, hypoplasia, occlusion and anatomical variation rate; and femoral approach contraindications or refusal); postoperative manual compression hemostasis; and voluntary participation in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: high bleeding risk (platelet count < 100,000/ml, hepatic disease, and estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 ml/min/m2); limb malformation on the preoperative puncture side; pain in the limb during the preoperative puncture; swelling of the limbs on the preoperative puncture side; cardiogenic shock; end-stage renal disease; and renal replacement therapy and scleroderma.

Randomization and blinding

Patients were randomly divided into a control group and a brace group at a 1:1 ratio according to a computer-generated random number table. The randomization codes were enclosed in sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed envelopes. The envelope was concealed by the first blinded investigator and delivered to the second investigator. The second investigator prepared 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices and labeled them with the patients’ names and registration numbers. The third investigator was in charge of wearing 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices. The fourth investigator assessed the outcomes of the study. The statisticians were also blinded to the treatment assignments.

Study protocol

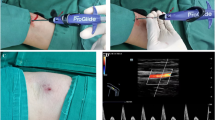

All patients underwent puncture of the common brachial artery via the modified Seldinger technique. Patients undergoing brachial artery intervention surgery received heparin based on their body weight (diagnostic: standard initial dose of 50 IU/kg for average weight of 60 kg; therapeutic procedures: standard initial dose of 100 IU/kg) with continuous administration every hour following placement of the interventional sheath, and manual compression was performed after the procedure by applying compression for at least 15 min until leakage had stopped. Closure device was not used on any patient. Brace group: after successful artificial compression hemostasis, the patient’s puncture arm was placed into the 3D-printed elbow external fixation brace, and the tightness of the brace was adjusted according to the patient’s arm circumference (Fig. 1). The 3D-printed elbow external fixation device is composed of one device fabricated by 3D printing and two fixation bands (Fig. 2). Control group: after hemostasis was established, “a figure of 8 elastic” pressure dressing with voluminous gauze “dolly” was applied, along with an arm extension immobilizer. The saturation of pulse oxygen was checked, and the fixation belt was adjusted so that the saturation of pulse oxygen was ≥ 95% and there was no bleeding at the puncture site. The nurse assessed the absence of bleeding risk and proceeded to remove all devices.

Assessments

The patients’ characteristics that were assessed were age, sex, sheath size, type of operation, duration of operation, intraoperative heparin, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulant medications consumption taken in the perioperative period. Data were recorded by researchers who were blinded to the purpose of the study.

The primary endpoints of the study were as follows:

-

Puncture site-related discomfort was assessed using a numeric rating scale (0 = no discomfort to 10 = worst imaginable discomfort). The severity of puncture site-related discomfort was considered “mild” when the NRS score was 0–3 (defined as reported by patients only on questioning), “moderate” when the NRS score was 4–6 (defined as mildly affecting sleep or being tolerable), and “severe” when the NRS score was 7–10 (defined as severely affecting sleep or being intolerable).

The second endpoints included the following:

-

The degree of swelling, including the upper arm calibration rate and forearm calibration rate, was calculated as the difference between the preoperative and postdevice removal arm circumferences at 10 cm above the elbow divided by the preoperative arm circumference at 10 cm above the elbow; the forearm calibration rate was defined as the difference between the preoperative and postdevice removal arm circumferences at 10 cm under the elbow divided by the preoperative arm circumference at 10 cm under the elbow;

-

The braking time was measured in minutes. The braking time was the time from removing the vascular sheath to removing all devices;

-

Bleeding classification and access-site bleeding according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) score;

-

The area of subcutaneous hemorrhage was measured by an uninformed nurse 24 h after the procedures;

-

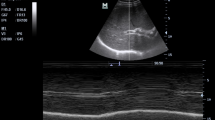

For any other complications, such as hematoma, bleeding, or thrombus, 24 h after the procedure, color duplex ultrasound was performed on all patients the day following the procedure by physicians who were blinded to the method of hemostasis applied.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

Sample size calculations were performed using PASS 15.0 (NCSS LLC., Kaysville, U.T., USA). Based on our unpublished data, 60% of patients experienced puncture site-related discomfort above a moderate grade at 24 h after undergoing diagnostic or interventional coronary procedures via brachial access. We assumed that a 3D-printed elbow external fixation device might decrease the incidence of puncture site-related discomfort above a moderate grade by 35%. Based on this assumption, our calculations showed that 62 patients in each group were needed to reach statistical significance, with two-sided α = 0.05 and β = 0.20. Considering a 15% dropout rate, 72 patients were included in each group.

The trial data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range, IQR), or number (priority). Continuous data were checked for normality using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Continuous normally distributed variables were compared using student’s t test, whereas the Mann‒Whitney and Wilcoxon tests were used for nonnormally distributed variables. Two or more proportions were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The per-protocol principle was applied when incomplete information was available, and a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

A total of 162 patients were assessed for eligibility before intervention. Among them, 16 patients were excluded, and 150 were randomized (Fig. 3). After randomization, one patient in the brace group was lost to follow-up because they were discharged within 24 h after intervention, while three patients in the control group were lost to follow-up for the same reasons.

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the brace group and the control group, indicating that the clinical data were comparable (Table 1).

The incidence of puncture site-related discomfort in the control group was different from that in the brace group at postoperative 24 h (mild: 36.1% vs. 59.5%, moderate: 56.9% vs. 37.8%, severe: 6.9% vs. 2.7%, P = 0.014) (Table 2). The puncture site-related NRS score at 24 h postsurgery was significantly lower in the brace group than in the control group [3(3-4) vs. 4(3-5), P = 0.006] (Fig. 3). Similarly, the upper arm calibration rate at 24 h postsurgery was significantly lower in the brace group than in the control group [0.024 (0.019–0.046) vs. 0.077 (0.038–0.103), P < 0.001], 12[24%] vs. 43[80%], as was the forearm calibration rate [0.026 (0.024–0.049) vs. 0.050 (0.023–0.091), P = 0.007] (Fig. 4). The time to hemostasis, bleeding classification, hematoma and thrombus at 24 h postsurgery was not significantly different between the brace and control groups. The brace group exhibited a significantly lower area of subcutaneous hemorrhage at 24 h postsurgery than did the control group [0.255 (0–1.00) vs. 1 (0.25–1.75) cm2, P = 0.003].

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, compared with simple manual compression, the 3D-printed elbow external fixation device combined with manual compression was associated with a lower incidence of puncture site-related discomfort, a lower degree of swelling in the arm, and a reduced area of subcutaneous hemorrhage in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures via brachial access. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first new 3D-printed device reported for use in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures via brachial access, and patient-reported comfort was used as an evaluation metric.

A systematic review encompassing five studies showed that brachial artery puncture is an excellent alternative strategy after radial artery puncture fails. This is because there is no difference in vascular complications, and the risk of bleeding at the brachial artery puncture site is lower than that at the femoral artery puncture site6. According to statistics, the incidence of coronary interventional surgery through the brachial artery in China is approximately 500/100,000, and in the United Kingdom, it is approximately 130/100,00013,14. At present, manual compression is the most commonly used method for hemostasis, followed by dressing and fixation with gauze. However, this method cannot effectively control bleeding, which can lead to pain, swelling, bleeding, and local vascular complications at the puncture site15. In recent years, the use of vascular closure devices (VCDs) after brachial artery puncture has increased, and a large number of studies have shown that there is no significant difference in adverse events between VCDs and manual compression in the brachial artery; however, VCDs may present risks of stenosis or occlusion due to local suturing of the punctured artery, potentially increasing the risk of hematoma and pseudoaneurysm8,16,17. Our study showed that the incidence of hematoma after diagnostic or interventional coronary procedures via brachial access was 1.4%, which was lower than the 9% hematoma incidence in previous studies8. In addition, we did not observe pseudoaneurysms, local neurological adverse events, or other adverse events in our study. Patient puncture site pain severity was not investigated in other studies. Our research showed that the moderate to severe puncture site pain in patients wearing 3D-printed braces after diagnostic or interventional coronary procedures via brachial access was significantly lower than that in the control group (40.5% vs. 63.8%).

After undergoing diagnostic or interventional coronary procedures, postoperative patients must adhere to strict immobilization requirements. This is because the brachial artery area has an abundance of muscles and soft tissues. When the elbow joint moves and the forearm rotates forward, the braking effect can be compromised, leading to insufficient immobilization and potential complications such as hemorrhage or pseudoaneurysm. In addition, excessive compression may lead to ischemia, numbness, swelling, and pain in the limb. These issues can cause discomfort at the puncture site. The better performance of the 3D-printed elbow external fixation device for preventing puncture site-related discomfort shown in this study may be explained in three ways. First, the greater comfort of 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices than traditional devices is probably related to the greater suitability of 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices because they are custom-made based on the patient's specific skeletal structure and needs. Second, the fixed brace can not only restrict the movement of the elbow joint but also limit the pronation of the forearm caused by the contraction of the pronator teres muscle originating from the lower segment of the humerus. Third, after the use of braces, patients feel a sense of security that the surgical site is being protected, resulting in a more relaxed physical and mental state. This helps to avoid discomfort caused by excessive tension and anxiety.

In this clinical study, we used more objective endpoints (upper arm and forearm calibration rate and area of subcutaneous hemorrhage) to evaluate the effectiveness of 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices. It is clear that 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices are superior to the control group in reducing arm swelling and subcutaneous hemorrhage, which we believe is mainly due to the reduced movement of the affected arm and the more suitable adjustment of the hemostatic device.

Previous studies have shown that the use of VCDs in the brachial artery following an endovascular procedure is equivalent to manual compression8,9. We found that, relative to traditional manual compression, the 3D-printed device showed no significant difference in terms of bleeding complication classification, hematoma or thrombus. As a result, we conclude that the safety of 3D-printed elbow external fixation devices is comparable to that of traditional external fixation devices. When the radial artery is not suitable, if the patient has contraindications for femoral artery puncture or refuses to undergo femoral artery puncture, brachial artery puncture can be selected. After surgery, patients can use a new type of elbow external fixation brace to improve comfort and reduce postoperative complications.

Nevertheless, as a single-center prospective trial, the current study has several limitations. First, because of the relatively small sample size of a clinical trial study, differences, such as bleeding, hematoma, and nerve damage, were not found between the two groups. However, the detection of these complications at a low incidence depends on observations with a larger sample size. Second, the follow-up time in this study was short, and our research excluded individuals at high risk of bleeding, cardiogenic shock, or severe kidney disease. Therefore, the applicability of this study to such patients remains to be determined. Third, 3D-printed elbow external fixation brace can be costly, but patients can choose according to their preferences, but all patients in this study received the 3D-printed devices free of charge. Additionally, the researchers assigning the wear braces could not be blinded to the group allocation, which may have biased the results. In later large-sample, multicenter clinical studies, we should also consider refining the design protocol to compensate for these inadequacies to obtain complete and accurate trial results.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures by brachial access, the novel elbow joint fixation device combined with manual compression is superior to simple manual compression for reducing puncture site-related discomfort, alleviating the degree of swelling, and minimizing the subcutaneous bleeding area. Additionally, no significant complications were observed.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author if there is a reasonable request.

References

Dehmer, G. J. et al. 2023 AHA/ACC clinical performance and quality measures for coronary artery revascularization: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on performance measures. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 16(9), e00121 (2023).

Goel, S. et al. Left main percutaneous coronary intervention-radial versus femoral access: A systematic analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 95(7), E201–E213 (2020).

Riangwiwat, T., Mumtaz, T. & Blankenship, J. C. Barriers to use of radial access for percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 96(2), 268–273 (2020).

Lawton, J. S. et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 145(3), e18–e114 (2022).

Mueller, R. L. & Sanborn, T. A. The history of interventional cardiology: Cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and related interventions. Am. Heart J. 129(1), 146–172 (1995).

Mele, M. et al. How brachial access compares to femoral access for invasive cardiac angiography when radial access is not feasible: A meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Access 27, 11297298221145752 (2022).

Kaluski, E., Shah, A. & Bianco, M. Brachial artery access: Easy way in…But cautious way out. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 21(10), 1274–1275 (2020).

Koziarz, A. et al. The use of vascular closure devices for brachial artery access: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 34(4), 677–684 (2023).

Koreny, M. et al. Arterial puncture closing devices compared with standard manual compression after cardiac catheterization: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 291(3), 350–357 (2004).

Claire, Y. et al. Photopolymerizable biomaterials and light-based 3D printing strategies for biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 120(19), 10695–10743 (2020).

Pavan Kalyan, B. G. & Lalit, K. 3D printing: Applications in tissue engineering, medical devices, and drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 23(4), 92–92 (2022).

Ho, K. L. et al. Personalized assistive device manufactured by 3D modelling and printing techniques. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 14(5), 526–531 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Trends in percutaneous coronary intervention in China: Analysis of China PCI registry data from 2010 to 2018. Cardiol. Plus 7, 118–124 (2022).

Protty, M. et al. Brachial arterial access for PCI: An analysis of the British cardiovascular intervention society database. EuroIntervention 17(13), 1100–1103 (2022).

Mantripragada, K., Abadi, K., Echeverry, N., Shah, S. & Snelling, B. Transbrachial access site complications in endovascular interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Cureus 14(6), e25894 (2022).

Yi, H. et al. A novel femoral artery compression device (butterfly compress) versus manual compression for hemostasis after femoral artery puncture: A randomized comparison. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 31(1), 50–57 (2022).

Kennedy, S. A. et al. Complication rates associated with antegrade use of vascular closure devices: A systematic review and pooled analysis. J. Vasc. Surg. 73(2), 722–730 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology, 2023JDKP0051. Deyang City Science and technology plan project, 2022SZ081. Deyang City Science and technology plan project, 2023SZZ003. Sichuan Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Name: Yue Zhang. Contribution: this author helped design and conduct the study, collect and analyze the data, and prepare and approve the final manuscript. Name: Qianlan Tao. Contribution: this author helped conduct the study. Name: Xia Xiao. Contribution: this author helped conduct the study. Name: Furong He. This author helped conduct the study. Name: Mengmeng Wang. Contribution: this author helped conduct the study and prepare and approve the final manuscript. Name: Dingxiu He. Contribution: this author helped design and conduct the study. Name: Yangyun Han. Contribution: this author helped prepare and approve the final manuscript. Name: Kaisen Huang. Contribution: this author helped design and conduct the study, collect and analyze the data, and prepare and approve the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Yang, M., Tao, Q. et al. Randomized study for a novel elbow joint fixation device on postoperative complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures through the brachial artery. Sci Rep 14, 20535 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71241-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71241-5