Abstract

To investigate the effects of high temperature and carbon fiber-bar reinforcement on the dynamic mechanical properties of concrete materials, a muffle furnace was used to treat two kinds of specimens, plain and carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete, at high temperatures of 25, 200, 400 and 600 °C. Impact compression tests were carried out on two specimens after high-temperature exposure using a Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test setup combined with a high-speed camera device to observe the crack extension process of the specimens. The effects of high temperature and carbon fiber-bar reinforcement on the peak stress, energy dissipation density, crack propagation and fractal dimension of the concrete were analyzed. The results showed that the corresponding peak strengths of the plain concrete specimens at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C were 88.37, 93.21, 68.85, and 54.90 MPa, respectively, and the peak strengths after the high-temperature exposure first increased slightly and then decreased rapidly. The mean peak strengths corresponding to the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens after high-temperature action at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C are 1.13, 1.13, 1.21, and 1.19 times that of plain concrete, respectively, and the mean crushing energy consumption densities are 1.27, 1.31, 1.73, and 1.59 times that of plain concrete, respectively. The addition of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement significantly enhanced the impact resistance and energy dissipation of the concrete structure, and the higher the temperature was, the more significant the increase. An increase in temperature increases the number of crack extensions and width, and the high tensile strength of the carbon fiber-bar reinforcement and the synergistic effect with the concrete material reduce the degree of crack extension in the specimen. The fractal dimension of the concrete ranged from 1.92 to 2.68, that of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens ranged from 1.61 to 2.42, and the mean values of the corresponding fractal dimensions of the plain concrete specimens after high-temperature effects at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C were 1.19, 1.21, 1.10, and 1.11 times those of the fiber-reinforced concrete specimens, respectively. The incorporation of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement reduces the degree of rupture and fragmentation of concrete under impact loading and improves the safety and stability of concrete structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is still widely used material today, and concrete buildings are used in a variety of complex environments. Due to the influence of the external environment, concrete buildings are often exposed to high-temperature conditions, such as hot areas, fires, geothermal heat, etc. The performance of concrete materials is affected by high temperatures, and many experts and scholars have carried out research in this field1,2,3,4,5,6. Miao et al.7 studied on the changes in the mechanical properties of concrete at different curing ages after high temperature exposure and reported that the compressive and tensile strengths at different ages exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing temperature and that the effect of high temperature on the strength of concrete at different curing ages was a deterioration phenomenon. Zhou et al.8 used XRD, thermal analysis and an electrohydraulic servo press to carry out research on the compressive strength of high-strength performance concrete after exposure to high-temperature effects and the mechanism of the high-temperature effect and reported that when high-strength high-performance concrete internally formed in a high-temperature autoclave environment, the compressive strength increased; additionally, at 500 °C and 800 °C high-temperature conditions, the high-strength high-performance concrete was added to the hydration products of the cement slurry as the temperature increased, resulting in a gradual decrease in the compressive strength of the concrete. Xie et al.9 explored the effect of temperature on the apparent characteristics, quality loss rate and mechanical properties of steel fiber mechanism sand concrete. They found that the high temperature affects the specimen quality loss; the temperature reaches 800 °C when the specimen quality loss rate reaches 9.6%. Similarly, the mechanical properties of specimens with 0.1% steel fiber doping are minimized by temperature. Zhou et al.10 explored the variation rule of the split tensile strength of C30 and C40 concrete under different high-temperature cooling modes through experiments. The results show that the quality decreases with increasing temperature, the degree of crack extension on the surface after high-temperature-water cooling is greater than that after high-temperature-natural cooling, the split tensile strength decreases, and the strength after high-temperature-water cooling decreases more than that after high-temperature-natural cooling. Dong et al.11 explored mixed-fiber concrete at different high temperatures after the compressive and tensile strength change rule. Their results showed that when the temperature reached 400 °C, the specimen compressive strength reached its peak, and the splitting tensile strength increased with increasing temperature and decreasing temperature. Ren et al.12 used an axial pulling test to explore the mechanism of high temperature after the action of the change rule of adhesion between sand concrete and steel and reported that high temperature decreases the strength and reinforcing steel materials by decreasing the adhesive strength and decreasing the rate of decrease with increasing temperature. Rong et al.13 analyzed the macromechanical properties of specimens by exploring the change in the internal pore structure after high temperature. They found that as the temperature of the specimen internal microporous ratio decreased, the proportion of medium pores and large pores increased, and when the temperature reached 800 °C, the specimen large pore proportion reached 72.26%. Moreover, the change in the pore structure and increase in the porosity decreased the specimen strength. Therefore, high temperatures degrade the pore structure of concrete materials, the bonding effect between concrete and steel bars and the mechanical properties, which greatly affects the safety of concrete buildings.

Due to the excellent compressive properties and weak tensile properties of concrete materials, adding reinforcement to concrete materials not only improves the mechanical properties but also enhances the ability of the specimen to resist external complex environments, such as high temperatures, low temperatures, corrosive environments, and loading effects14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In previous research on the change in reinforced concrete material properties, Li et al.21 explored the uniaxial compressive mechanical properties of specimens after high-temperature plain concrete columns and reinforced concrete columns through experiments and reported that the modulus of elasticity and the peak stress decreased after high-temperature action, the peak strain increased, the stress reduction in plain concrete was significantly greater than that in reinforced concrete, and the adhesion between the steel reinforcement and the concrete enhanced the ability to resist external loads. Hu et al.22 studied the dynamic properties of reinforced foam lightweight concrete in the transition section of roads and bridges. Their results showed that an appropriate amount of fiber admixture significantly enhanced the specimen strength and modulus of elasticity and that reinforced foam lightweight concrete could effectively reduce structural vibration and enhance the safety of roads, bridges and buildings. Pan et al.23 found that the addition of fibers can increase the base material cohesion, and the shear performance of the specimen significantly improved. Zhu et al.24 studied on the load carrying capacity of concrete beams reinforced by prestressed reinforced carbon fiber plates and found that prestressed reinforced carbon fiber plates can improve the amorphosis capacity of the structure and enhance the ductility of the specimen itself. Huang et al.25 explored the thermal conductivity and deformation law of reinforced concrete under temperature and stress through tests and found that the incorporation of steel fibers can effectively enhance the thermal conductivity of concrete and reduce the maximum strain. Therefore, adding reinforcement bars to concrete material can enhance the mechanical properties and deformation resistance of the material and enhance the safety performance of the structure.

Although reinforced concrete structures are widely used, reinforced materials are prone to rusting and corrosion, which accelerates corrosion in coastal and salt lake environments, and such reinforcements are prone to deformation at high temperatures26,27,28. Therefore, special reinforcement bars should be used to replace some special buildings. Carbon fibers have good tensile strength, elastic modulus, alkali resistance, heat resistance, corrosion resistance and other properties and can effectively improve the properties29,30; in some special environments, they can be good substitutes for reinforcements. At present, there are many studies of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete, but there are few studies of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete after exposure to high-temperatures. Moreover, the mechanical properties of concrete materials under dynamic loading are different from those under static loading31,32,33,34,35,36. Therefore, it is important to explore the dynamic mechanical properties of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens after exposure to high temperatures to outline the safety performance of concrete buildings in high temperature environments.

To further investigate the changes in the properties of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete materials under dynamic loading after high-temperature action, dynamic tests were carried out on plain concrete and carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete at different high temperatures (25, 200, 400, and 600 °C) by using an SHPB device, and the tests were carried out on carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete at different high temperatures (25, 200, 400, and 600 °C). Combined with the high-speed camera device used to determine the crack expansion process of the specimen, the influence of the carbon fiber-bar reinforcement, temperature on the specimen dynamic compression strength, energy consumption density, crack expansion process and fractal dimension of rupture and fragmentation was analyzed. The research results can provide a test basis for the safety and stability of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete building structures, and the test process is shown in Fig. 1.

Test

Specimen preparation

P·O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement was used as the raw material for concrete preparation, and some of its parameters are shown in Table 1. Natural river sand was selected as the fine aggregate, and its density was 2650 kg m−3. The coarse aggregate is made of granite with a particle size of 5–15 mm. The water used was laboratory tap water, an admixture of polycarboxylic acid superplasticizer, and a water reduction efficiency of 25%. The mix ratio of each material of concrete was cement:water:fine aggregate:coarse aggregate:water reducer = 3:1:3.3:7.5:0.06. The carbon fiber reinforcement bars were arranged according to the steel structure of the reinforced concrete structure. The physical performance parameters of the carbon fiber bars are shown in Table 2. All the materials were evenly stirred according to the mixture ratio and placed in a mold with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 50 mm. The carbon fiber reinforcement bar was fixed in the mold to produce a standard cylinder specimen. After pouring, the specimens were placed in a curing room with relative humidity ≥ 95% and temperature maintained at 20 ± 2 °C for standard curing for 28 days. After the end of curing, the two end faces of the specimen were polished and smooth, and the end face roughness was less than 0.02 mm37,38,39. The spatial structure of the reinforcement bars and the standard specimen are shown in Fig. 2.

Test programs and devices

After reaching the age of curing for high-temperature treatment of plain and reinforced concrete specimens, the numbered specimens were placed in muffle furnace for high-temperature heating. The rated power of the instrument is 6 kW, the maximum temperature reached was 1200 °C, the rate of temperature increase was 5 °C/min40, the temperature increased to a predetermined temperature for 6 h after the constant temperature treatment, and the temperatures were set to 25, 200, 400, 600, and 800 °C. The specimens were naturally cooled to room temperature at the end of the high-temperature treatment. After exposure to 800 °C, the integrity of some of the specimens could not be maintained, and thus, the specimens were damaged; therefore, the results for the 800 °C high-temperature specimens were excluded. After all the high-temperature specimens were processed, dynamic impact loading pretests were carried out, and the final selected impact air pressure was 0.2 MPa.

An impact compression test was carried out with a separate SHPB device with a diameter of 74 mm41. The test device is shown in Fig. 3. A high-speed camera device was used to observe the cracking and crushing process of the specimen under impact loading, in which the time interval of image acquisition was 10 µs. The stress, strain, strain rate and energy were calculated by the three-wave method, and the waveform and typical stress balance curve were obtained, as shown in Fig. 4. The calculation formula is as follows:

where \(\dot{\varepsilon }(t)\), \(\varepsilon (t)\), and \(\sigma (t)\) are the strain rate, strain and stress, respectively. \(\varepsilon_{{\text{i}}} (t)\), \(\varepsilon_{{\text{r}}} (t)\), and \(\varepsilon_{{\text{t}}} (t)\) are the incident strain, reflected strain, and transmitted strain, respectively. l is the height. C0 is the longitudinal wave velocity. E is the modulus of elasticity. A is the cross-sectional area, and As is the cross-sectional area of the specimen. \(W_{{\text{i}}}\), \(W_{{\text{r}}}\), \(W_{{\text{t}}}\), and \(W_{{\text{s}}}\) are the incident, reflected, transmitted, and dissipated energy. \(\varepsilon_{{\text{d}}}\) is the crushing energy dissipation density, and V is the volume.

Results

Stress change pattern

The stress changes in the plain concrete and carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens under impact loading were analyzed, and the changes in the stress‒strain curves atdifferent temperatures are shown in Fig. 5. The appearance of the plain concrete specimen treated at 600 °C is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 5 shows that the stress‒strain curves of the two concrete under impact loading exhibit the same trend. With increasing loading time, the specimen stress and strain increase, and the stress‒strain curve in the preloading period linearly increases. As the load continues to increase, the time required for the specimen stress to increase significantly decreases; this time, the slope of the stress‒strain curve decreases, the specimen strain increment becomes more significant. When the specimen reaches the peak stress, the strength is continuously reduced, the strain continues to increase, the specimen loses its load-bearing capacity, and the increase in deformation causes crack expansion and destruction. The peak stress of plain concrete specimens at 25, 200, 400 and 600 °C is 88.37, 93.32, 69.10 and 55.01 MPa respectively, and the peak strain is 0.0045, 0.004, 0.0067 and 0.0095 respectively. The corresponding peak stress of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens is 101.22, 103.36, 81.05, 70.15 MPa, and the peak strain is 0.011, 0.012, 0.016, 0.007. The peak stress increases first and then decreases, and the peak strain increases as a whole. Figure 5a shows that the corresponding peak strengths of the plain concrete at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C are 88.37, 93.21, 68.85, and 54.90 MPa, respectively. As the temperature increases, the peak stresses of both types of concrete decrease overall, and the peak strains increase. An increase in temperature causes the water inside the specimen to evaporate, the bonding effect between the aggregates to decrease, the number of cracks to increase, and internal damage to the specimen42. On the other hand, high temperature—cooling process will occur in the aggregate volume expansion and contraction of the specimen internal crack newborn and expansion, the specimen mechanical properties are reduced and the higher the temperature the greater the degree of damage. A comparison of the stress‒strain curves reveals that the peak strength of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens under the different high temperatures is significantly greater, indicating that the addition of carbon fiber-bar reinforcements substantially increases the resistance to dynamic loading. It can be seen from Fig. 6 that a small number of micro cracks spread on the surface of the specimen after the action at 600 °C, and these crack areas are also weak bearing areas of the specimen. Under the action of load, cracks are more likely to spread and the strength of the specimen decreases.

To further quantitatively analyze the change rule of the mechanical properties of the two kinds of concrete after exposure to different high temperatures, the specimen peak stress and strain were fitted. The changes in the peak stress and strain of the plain concrete with respect to temperature are shown in Fig. 7, and the changes in the peak stress and strain with respect to temperature are shown in Fig. 8.

Combined with Fig. 7, Fig. 8 shows that with increasing temperature, the peak stress of the two concrete specimens exhibited a small increase followed by a rapid decrease. The peak stress exhibited a quadratic negative correlation with temperature, and the temperature of the two specimens reached a maximum at 200 °C when the peak stress reached its maximum value. This is due to the increase in temperature between 25 and 200 °C so that water vapor forms within the specimen interior, thus causing the specimen to experience a “steam curing”, additional internal hydration of the cement paste, increased cement hydration to fill the specimen inside the primary cracks, and increased specimen density and integrity. On the other hand, water evaporation and escape cause hydrated calcium silicate to undergo a dehydration reaction, which further promotes tightening of the cement paste and enhances chemical bonding and adhesive strength, which leads to strength increase of post-high-temperature concrete and a consequent increase in the ability to resist external loads9. The strength of the specimens decreased significantly with a further increase in temperature. This is because the further increase in temperature makes the hydration product, Ca(OH)2, decompose and the C–S–H colloid loses water after the decomposition; the reduced amount of gelling material makes the aggregate cohesion lower2,6,43. Moreover, the free water produced by decomposition continues to transform into water vapor, the internal vapor pressure rises, and the volumetric contraction of cement paste and thermal expansion of aggregates under high temperature accompanied by the decomposition of hydration products accelerate the expansion of cracks to a certain extent so that macroscopic microcracks are visible to the naked eye and appear on the surface. When the temperature reaches 600 °C or more, due to the violent decomposition of the hydration products in the concrete cement paste C–S–H gel, the complex almost completely loses its binding water, leading to a large number of changes in the noncementing ability of C2S. Moreover, the specimen cannot maintain its own integrity and is fractured and crushed, such as during the 800 °C high-temperature treatment. With increasing temperature, the specimen peak strain overall tends to increase, and the reduction in interaggregate cohesion and the expansion of primary cracks increase the susceptibility of the specimen to deformation. Moreover, the specimen will experience a greater amount of deformation upon the arrival of the peak stress.

A comparison of the two concrete at high temperature after the action of strength changes can be seen in the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C high temperature after the action of the corresponding peak strength mean values of 100.63, 103.81, 83.27, and 67.74 MPa, respectively. Similarly, the average values of the peak strength of the concrete specimens were 89.16, 91.53, 68.93, and 57.03 MPa, respectively. The mean peak strengths corresponding to the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens after high-temperature action at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C were 1.13, 1.13, 1.21, and 1.19 times greater than those of plain concrete, respectively. The incorporation of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement significantly increased the impact resistance of the concrete structure, and the increase was more significant at higher temperatures. Due to the excellent compressive properties of concrete materials and low tensile strength, while carbon fiber-bar reinforcements have high tensile strength, the presence of carbon fiber reinforcing bars under the action of an external impact can support part of the tensile stress to reduce damage to the concrete material. On the other hand, the carbon fiber reinforcing bars form a bond with the concrete material, and the presence of a spatial mesh structure greatly enhances the internal integrity, so the strength of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimen is high. A comparison of the rate of strength loss under the action of high temperature shows that the strength reduction in plain concrete is more significant after the action of high temperature. This is because the high-temperature effects of carbon fiber-bar reinforcements and concrete materials on the coefficient of thermal expansion are not consistent, and the thermal expansion effect causes the carbon fiber-bar reinforcements and concrete materials to experience extrusion to a certain extent to enhance the reinforcing bar and the adhesion between the cementitious materials, which results in a reduced rate of stress loss in the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens.

Patterns of change in energy dissipation

The process of each energy change in the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete under impact loading at 25 °C is shown in Fig. 9. The relationship between the crushing energy dissipation density per unit volume and temperature under impact loading for both concrete specimens is shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 9 shows that the specimen under impact loading increases with time, and the trend of the growth of each form of energy is the same. From the energy time curve, the energy change can be roughly divided into three stages: in 0–50 μs, the growth of each form of energy is not obvious, the stress wave is on the rise in this stage, there are many primary cracks inside the concrete, and the internal cracks are compacted under the loading and the energy is stored. The energies steadily increase in 50–250 μs, and the reflected energy is greater than the transmitted and absorbed energies. This is due to the large difference in wave impedance between the incident bar and the concrete. Reflection occurs on the contact surface between the incident bar and the specimen, most of the energy in the form of waves is reflected back, a small portion of the energy can be propagated through the concrete specimen in the transmissive bar, and the rest of the energy is absorbed by the concrete specimen. This energy is stored in the way of elastic energy and acts on the specimen and causes plastic damage on the specimen; additionally, it is used for the expansion of specimen cracks and new cracks44. After 250 μs, the action of the stress wave ends, and the energies no longer increase and converge to a constant value.

Figure 10 shows that the crushing energy consumption density per unit volume of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete is significantly greater. The mean values of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens corresponding to the crushing energy consumption density per unit volume after high-temperature exposure at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C were 1.27, 1.31, 1.73, and 1.59 times greater than those of plain concrete, respectively. Compared with plain concrete, the addition of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement can form a spatial support structure inside the concrete specimen to enhance the integrity of the specimen; on the other hand, when the external energy input increases in addition to the cracks in the concrete itself, the carbon fiber-bar reinforcement of the high-strength performance concrete will absorb energy from the outside, and the high compressive strength and carbon fiber reinforcing bar will contribute to the formation of high tensile strength and the synergistic effect of the specimen to greatly enhance the effect of energy dissipation. There is a quadratic negative correlation between the crushing energy dissipation density of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete and temperature and a linear negative correlation for plain concrete, where an increase in temperature causes deterioration of the concrete material, which reduces the energy dissipation effect. The crushing energy consumption density of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete was always greater than that of plain concrete, and the incorporation of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement led to a significant increase in the mechanical properties and energy consumption of the specimens.

Crack expansion

The crack growth process of two kinds of concrete specimens under impact loading was assessed via a high-speed camera device. The crack growth processes of the 0 °C, 200 °C, 400 °C and 600 °C plain concrete specimens are shown in Fig. 11, and the crack growth processes of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens are shown in Fig. 12.

Figures 11 and 12 show that the specimen maintains its integrity during the preloading period. With the propagation of the stress wave inside the specimen, the original equilibrium state inside the specimen breaks, and the uneven distribution of the fine internal structure of the concrete itself forms an uneven stress field, which exacerbates the stress at the original defects during the propagation process of the stress wave. Under stress, the crack structure undergoes complex evolution, the aggregate particles are stripped from each other, a large number of new cracks are formed and developed, the cracks are interconnected, and the specimen is first damaged along the weak structural surface. Cracks were generated on the surface of all the specimens at 70 µs, and as the loading time increased, the crack extension of the specimens increased until it penetrated the whole specimen and was accompanied by the generation of new cracks and the separation of the aggregates. Combined with the one-dimensional stress wave propagation law and the damage form, it can be seen that the tensile strength is much lower than the compressive strength. Under the action of impact loading, tensile cracking first occurs in the specimen, and as the repeated propagation of the stress wave inside the tensile crack extension increases, the number of cracks increases, while the expansion of cracks in the specimen prevent the specimen from maintaining its own integrity, allowing damage to occur.

The degree of crack extension in both concrete specimens under impact loading increased with increasing temperature. At 25 °C, the plain concrete produced one main tensile crack along the middle part, and a large number of microcracks derived from the lower part were accompanied by a small amount of aggregate spalling. Carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete produced one main tensile crack along the middle part, accompanied by a small amount of particle separation in the lower part. At 400 °C, the plain concrete specimens produced one main crack along the middle part, many microcracks developed in the upper part of the specimen, and with the extension of the cracks, the upper part of the specimen was significantly crushed at 350 µs. The upper end of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete produced two main cracks that penetrated at 350 µs; these cracks ruptured and shattered significantly less than those in the plain concrete. At 600 °C, many cracks appear on the surface of the plain concrete specimen, and as the stress wave cracks continue to expand and penetrate, the specimen gradually loses its integrity, which is accompanied by the peeling of many fragments. The carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens also exhibited a large number of cracks. As the stress wave action time increased, the cracks continued to expand, but the overall degree of rupture was significantly lower. An increase in temperature resulted in an increase in the number of internal cracks and a decrease in the adhesion between the aggregates so that the degree of crack extension and rupture and fragmentation increased significantly under the same impact load. A comparison of the degree of crack expansion in the two different concrete specimens reveals that the degree of crack expansion in the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens after exposure to the same high temperature is significantly lower than that in the plain concrete specimens. The incorporation of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement can bear part of the tensile load, and the synergistic effect of the concrete material greatly enhances the resistance to the external load.

Rupture crushing pattern and fractal dimension of two concrete specimens

The rupture and crushing patterns of the two concrete under impact loading after high-temperature action are shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13 shows that the two concrete specimens exhibited the coexistence of split tensile damage and axial compression damage modes under impact loading. As the temperature increases, the specimen fragment size decreases, the number of fragments increases, and the degree of rupture and fragmentation increases. An increase in temperature causes the internal fracture scale of the specimen to increase, and the aggregate bonding effect decreases; thus, for the same impact load, the specimen rupture crushing degree increases significantly, and as the temperature increases, the specimen transitions from tensile damage to crushing damage. A comparison of the two kinds of concrete specimens at the same high temperature after specimen rupture revealed that the fragmentation of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens was greater, the number of specimens was lower, and the fragmentation of the 400 and 600 °C specimens could be clearly observed in the carbon fiber-bar reinforcing bars and in the aggregates due to good adhesion. Therefore, the high strength of carbon fiber-bar, carbon fiber-bar reinforcement and aggregate between the good bonding effect and concrete and carbon fiber-bar reinforcement skeleton between the “synergistic” effect of the joint influence of the specimen to resist the deformation of the external load under the destructive capacity of a significant increase.

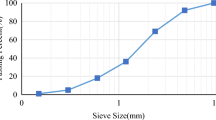

To further quantitatively investigate the degree of rupture and fragmentation of concrete under impact loading at two different high temperatures, the three-dimensional fractal dimension of concrete fragments is introduced. According to the existing research results, the crushed concrete that is obtained after impact at high temperature conforms to the G-G-S distribution, and the crushed specimens were screened using a set of standard screens45. The sieve aperture intervals ranged from 0.045 to 0.09 mm, 0.09 to 0.18 mm, 0.18 to 0.5 mm, 0.5 to 0.85 mm, 0.85 to 1.4 mm, 1.4 to 2.8 mm, 2.8 to 5.2 mm, 5.2 to 10 mm, 10 to 12 mm, 12 to 15 mm, and 15 to 20 mm, and the distribution equations were obtained from the mass‒frequency relationship:

where r is the particle size; rm is the maximum size; and b is the fragment distribution parameter, that is, the slope of the ln[mr/mT] − lnR curve.

According to the fractal dimension principle N = r−D (where N is the number with a particle size greater than r and D is the fractal dimension), which is also associated with the relationship between the increment in the number of fragments and the increment in the mass, the fractal dimension D was calculated from the mass-particle size relationship46. Among the two kinds of concrete after high-temperature treatment, the change in the mean fractal dimension is shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14 shows that the fracture fractal dimension of two concrete specimens under impact loading increases with temperature, and there is a positive linear correlation. The fractal dimensions of the plain concrete in the test range were between 1.92 and 2.68, those of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens were between 1.61 and 2.42, and the fractal dimension of the plain concrete specimens was always greater than that of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens. The mean values of the corresponding fractal dimension of the plain concrete specimens after high-temperature action at 25, 200, 400, and 600 °C were 1.19, 1.21, 1.10, and 1.11 times greater than those of the concrete specimens with carbon fiber-bar reinforcement. Despite the effect of high temperature on the degree of rupture and fragmentation, the incorporation of carbon fiber-bar reinforcement greatly enhances the deformation ability of the specimens to resist external loads so that the deformation and damage effects are significantly reduced under the same impact load, which greatly enhances the safety and stability of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete structures. Therefore, in high-temperature, highly corrosive environments where steel reinforcing materials are not suitable for reinforcing concrete structures, the incorporation of carbon fiber reinforcing bars can also greatly enhance the structural properties of concrete, including peak stress, crushing energy dissipation density, and resistance to crack expansion and deformation under external loads. This research provides new ideas for enhancing the dynamic load resistance, safety, and stability of concrete structures in special environments.

Conclusion

-

(i)

The peak strength of both the plain concrete and the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens decreases with increasing temperature. The average peak strengths of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens heated at high temperatures (25, 200, 400 and 600 °C) are 1.13, 1.13, 1.21 and 1.19 times greater than those of plain concrete, respectively. The presence of carbon fiber rod can improve the strength and high temperature resistance of concrete material.

-

(ii)

The average energy dissipation density per unit volume of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens at high temperatures of 25, 200, 400 and 600 °C is 1.27, 1.31, 1.73 and 1.59 times that of plain concrete, respectively. The high strength of carbon fiber reinforced concrete itself and the synergistic effect with concrete materials enhance the energy dissipation effect.

-

(iii)

Under an impact load, the crack propagation degree of the two concrete specimens increases with increasing temperature. At the same high temperature, the crack propagation degree of the carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens is significantly lower. The addition of carbon fiber reinforcement greatly enhances the deformation resistance of the specimen under external load, and significantly improves the resistance to crack propagation.

-

(iv)

The fracture tensile failure and axial compression failure modes coexist, and the fractal dimension is linearly positively correlated with temperature. The average fractal dimensions of plain concrete specimens subjected to high temperatures of 25, 200, 400 and 600 °C are 1.19, 1.21, 1.10 and 1.11 times greater than those of carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete specimens, respectively. The constrained reinforcement of the carbon fiber bars reduces the fracture degree. The addition of carbon fiber reinforcement can significantly improve the safety performance of concrete buildings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mahmoud, K. A. Overview of factors affecting the behavior of reinforced concrete columns with imperfections at high temperature. Fire Technol. 58(2), 1–37 (2021).

Yang, X. R. High-temperature performance of lining concrete for subsea tunnel. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. (English Edition) 12(3), 53–59 (2018).

Maziar, F. & Mahdi, N. Evaluation of post-fire pull-out behavior of steel rebars in high-strength concrete containing waste PET and steel fibers: Experimental and theoretical study. Constr. Build. Mater. 299, 123917 (2021).

Wu, D. P. et al. Study on the constitutive relationship between ordinary concrete and nano-titanium dioxide-modified concrete at high temperature. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 16(14), 4910 (2023).

Sahan, A. H. & Semsi, Y. Effect of different parameters on concrete-bar bond under high temperature. ACI Mater. J. 111(6), 633–639 (2014).

Chen, X. D. et al. Experimental investigation of the residual physical and mechanical properties of foamed concrete exposed to high temperatures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 33(7), 04021162 (2021).

Miao, L. A., Zhang, J. Y. & Yuan, G. L. Research on mechanical properties of concrete after high temperature at different ages. Fire Sci. Technol. 40(3), 330–333 (2021).

Zhou, N. N. Research on the mechanism of the effect of high temperature on the compressive strength of high-strength and high-performance concrete. New Build. Mater. 48(4), 14–17+21 (2021).

Xie, K. Z. et al. Experimental study on mechanical strength of steel fiber mechanism sand concrete after high temperature. Concrete 5, 1–5 (2022).

Zhou, J. C., Chen, H. B. & Wang, B. B. Experimental study on splitting tensile strength of concrete after high temperature. Fire Sci. Technol. 40(9), 1301–1304 (2021).

Dong, Y. J. et al. Study on mechanical properties of hybrid fiber concrete after high temperature. Compos. Sci. Eng. 5, 62–65+70 (2019).

Ren, X. Z., Han, Y. & Zhang, Y. Experimental study on bonding properties of machined sand concrete and steel bar after high temperature. Concrete 10, 51–54+58 (2020).

Rong, H. R. et al. Experimental study on the change of concrete strength and pore structure after high temperature. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 38(5), 1573–1578 (2019).

Yan, L. B. & Chouw, N. A comparative study of steel reinforced concrete and flax fibre reinforced polymer tube confined coconut fibre reinforced concrete beams. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 32(16), 1155–1164 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Comparison of the structural behavior of reinforced concrete tunnel segments with steel fiber and synthetic fiber addition. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 103, 04021162 (2021).

Kumar, M. R. et al. Modeling and simulation of mechanical performance in textile structural concrete composites reinforced with basalt fibers. Polymers 14(19), 4108–4108 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Comparative study of steel-FRP, FRP and steel-reinforced coral concrete beams in their flexural performance. Materials 13(9), 2097 (2020).

Gopinath, S. et al. Behaviour of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with basalt textile reinforced concrete. J. Ind. Text. 44(6), 924–933 (2015).

Li, W. W. et al. A proposed strengthening model considering interaction of concrete-stirrup-FRP system for RC beams shear-strengthened with EB-FRP sheets. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 37(10), 685–700 (2018).

Kara, I. F. et al. Deflection of concrete structures reinforced with FRP bars. Composites Part B 44(1), 375–384 (2013).

Li, M. T. et al. Experimental study on temperature effect of mechanical properties of plain concrete and reinforced concrete. Concrete 11, 68–73 (2017).

Hu, W. H. Study on dynamic characteristics of reinforced foamed lightweight concrete transition section of road bridge. Subgrade Eng. 2, 105–109 (2019).

Pan, B. et al. Study on shear strength of fiber-reinforced vegetated concrete under dry and wet cycle. J. China Three Gorges Univ. (Natural Sciences) 42(1), 63–67 (2020).

Zhu, W. X. et al. Experimental study and bearing capacity calculation of prestressed reinforced carbon fiber plate reinforced concrete beam. Build. Struct. 49(24), 102–106 (2019).

Huang, W. et al. Experimental study on deformation properties of reinforced concrete for energy pile body under temperature and stress. Rock Soil Mech. 39(7), 2491–2498 (2018).

Jiao, H. T. et al. Evaluation of corrosion fatigue life of reinforced concrete structures in chloride environment. Concrete 3, 48–53 (2023).

Yang, D. D., Liu, F. Q. & Yang, H. Analysis of fire resistance of reinforced concrete columns confined by square steel tubes with unequal constraints at both ends. J. Build. Struct. 44(2), 165–176 (2023).

Lu, C. G. et al. Durability life prediction of reinforced concrete in corrosion environment based on Weibull distribution. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 30(6), 1534–1544 (2022).

Patchen, A., Young, S. & Penumadu, D. An investigation of mechanical properties of recycled carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete. Materials 16(1), 314 (2022).

Kizilkanat, A. B. Experimental evaluation of mechanical properties and fracture behavior of carbon fiber reinforced high strength concrete. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 60(2), 289–296 (2016).

Zheng, D., Li, Q. B. & Wang, L. B. Rate effect of concrete strength under initial static loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 74(15), 2311–2319 (2006).

Ning, J. G., Liu, H. F. & Shang, L. Dynamic mechanical behavior and the constitutive model of concrete subjected to impact loadings. Sci. China Ser. G Phys. Mech. Astron. 51(11), 53–59 (2008).

Wang, Z. L. & Yang, D. Study on dynamic behavior and tensile strength of concrete using 1D wave propagation characteristics. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 22(3), 184–191 (2015).

Zhou, X. Q. & Hao, H. Mesoscale modelling of concrete tensile failure mechanism at high strain rates. Comput. Struct. 86(21), 2013–2026 (2008).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Dynamic splitting tensile behaviors of ceramic aggregate concrete: An experimental and mesoscopic study. Struct. Concrete 23(5), 3267–3283 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Dynamic and damage characteristics of mortar composite under impact load. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27(3), 1383–1395 (2023).

Qi, Z. et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of rape straw ash concrete under impact load. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Natural Sciences) 43(3), 336–339 (2017).

Li, Q. M. & Meng, H. About the dynamic strength enhancement of concrete-like materials in a split Hopkinson pressure bar test. Int. J. Solids Struct. 40(2), 343–360 (2003).

Wang, M. X., Wang, H. B. & Zong, Q. Analysis of dynamic mechanical properties and fracture characteristics of coal mine mudstone. J. Vib. Shock 38(4), 137–143 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Study on the dynamic impact mechanical properties of high-temperature resistant ultra-high performance concrete (HTRUHPC) after high temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109752 (2024).

Wei, J. H. et al. Effect of replacing freshwater river-sand with seawater sea-sand on dynamic compressive mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 419, 135473 (2024).

Arel, H. S. & Semsi, Y. Effect of different parameters on concrete-bar bond under high temperature. ACI Mater. J. 111(6), 633–639 (2014).

Mathew, G. & Paul, M. M. Mix design methodology for laterized self compacting concrete and its behaviour at elevated temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 36, 104–109 (2012).

Wang, M. X., Wang, H. B. & Zong, Q. Experimental study on energy dissipation of coal mine mudstone under impact load. J. China Coal Soc. 44(6), 1716–1725 (2019).

Yang, J., Jin, Q. K. & Huang, F. L. Theoretical model and numerical calculation of rock blasting (Science Press, 1999).

He, M. C. et al. Classification and research methods of rock burst experimental debris. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28(8), 1521–1529 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Educational Committee(2023AH051167) and Anhui University of Science and Technology high-level talent research start-up fund (2022yjrc78).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Hao Wang.; methodology, Hao Wang.; formal analysis, Hao Wang.; resources, Q.Z.; data curation, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Lv, N., Lu, Z. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties and breakage of high temperature carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete under impact load. Sci Rep 14, 20566 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71292-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71292-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Numerical simulation on residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Experimental investigation on structural behavior of composite slabs with steel decking, fiber-reinforced concrete, and lightweight aggregate concrete layers

Scientific Reports (2025)