Abstract

Risk cascading propagation research mostly focuses on complex theoretical networks. Recently, the vulnerability of international chip supply has increased notably, and it is strategically important to explore how shortage risk affects the emergence dynamics of the real chip trade systems. This study abstracts the global chip trade relationship data for 2009–2021 into multiple asymmetrically weighted networks. Using macro-network and micro-node indicators, we explore the topological traits of international chip trade networks and their evolutionary laws. Accordingly, we propose risk cascading propagation models driven by node failure and edge restraint and further innovate to open up the research paradigm of focused-edge networks. Furthermore, a community infection-driven risk cascading propagation mechanism that incorporates community risk absorption capacity is introduced, considering both the propagation attenuation effects and the trade dependency degree. A multi-dimensional dynamic perspective reveals the hidden systemic risks in international chip trade. The main results are as follows: first, international chip trade networks are highly connected and cohesive, consistent with small-world characteristics. Second, the proportion of economies that collapse because of supply shortage risk shocks increases with the impact coefficient \(\alpha /\beta\). The dominant power in chip crisis propagation has shifted from Europe and America to Asia, and mainland China’s risk penetration capacity has enhanced significantly. Third, focused-edge networks conform to a multi-hub radiation pattern. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the degree of control and spillover effects of chip supply shortages in hub economies on the international trade was increasing progressively. Fourth, an increase in absorption capacity \(\lambda\) or attenuation factor \(\gamma\) consistently leads to a decline in avalanche scale, with \(\lambda\) exhibiting critical thresholds. These findings will help policymakers pursue efficient management strategies for chip trade, thereby improving supply stability and security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a power engine for optimizing production structures in the digital era, the chip industry is crucial for realizing a high level of science and technology, completing a modernized economic system, and guaranteeing national security. The development of the chip industry requires nations to make long-term investments in R &D expenses and steadily accumulate chip manufacturing technologies. Each country has advanced considerably differently in the chip industry, owing to uneven resource endowment and production levels1. Most countries remain in the catch-up stage, which makes it challenging to meet the rising demand for chips through self-sufficiency alone. Thus, the international chip trade naturally functions as a potent tool for regulating the equilibrium of supply and demand. In 2021, global chip exports and imports totaled USD 1.4 trillion2. Intricate transaction relationships between countries form tightly connected and mutually influential international chip trade networks. Exploring the evolutionary characteristics of complex chip networks from global and temporal perspectives can assist decision-makers in responding to future changes with sufficient prior information and constructing a scientific and reasonable allocation mechanism to guarantee a stable supply of chip resources.

The chip industry serves as an essential driving force for national and world economic expansion, making it the primary battleground for key technology games and competition in high-tech fields. In 2019, Japan imposed export restrictions on South Korea for three core materials necessary for semiconductor manufacturing: hydrogen fluoride, fluorinated polyimide, and photoresist3. In 2022, the Sino-US trade war continued to ferment: the US ‘Entity List’ expanded on a large scale. In the same year, the US government signed the CHIPS and Science Act and attempted to establish a semiconductor alliance with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The aim is to impose constraints on mainland China’s advanced chip cooperation4,5. These trade frictions have disrupted resource allocation in the original chip industry and supply chains. Moreover, the regional blockade and restrictive non-tariff measures triggered during the rapid spread of COVID-19 have affected the international logistics system6; uncertainties in the cooperation of the global chip production chain have increased, lowering the overall supply efficiency. However, prevention and control measures, such as home offices and online education, have spawned a surge in demand for chips in downstream industries7, including mobile phones, tablet PCs, and computers. Recently, under the combined effect of multiple factors, the aggravating contradiction between supply and demand has intensified the global shortage of chips8, causing a noticeable increase in the vulnerability of international chip supply. Therefore, it is strategically important to explore the penetration mechanisms of shortage risks in chip trade systems.

Current studies have discussed the aforementioned context. First, most of the literature on the chip trade focuses on the deconstruction of policy strategies4,9 or insights into implications in frictional environments4,10 and seldom employs complex network theory to examine the changing patterns in the structural characteristics of the international chip trade. Well-established complex network analyses11,12,13 have been widely applied to the quantitative investigation of trade relations in various strategic industries. Based on product structure, network structure, and influencing factors, Duan et al. explored the spatial evolutionary pattern of the global trade system for high-tech products. They explained the trading features of China’s high-tech products in detail12. There are also studies from the perspective of the industry chain. Ren et al. concentrated on the structural differences of the key semiconductor production links in global trade while revealing the dynamic evolutionary laws of asymmetric dependence between countries13. The literature primarily focuses on studying changing trends in the trade structure. Although the fields differ, they can also provide a series of inspirations and statistical indicators for mining international chip trade network characteristics. Second, previous literature has predominantly focused on the causes, impacts, and mitigation measures of the chip shortage10,14. Mohammad et al. provided an overview of the semiconductor supply chain, focusing on its vulnerabilities and the principal causes of shortages. They found that establishing a resilient supply chain is essential for mitigating or eliminating the impact of such disruptions15. Contrary to previous static risk analyses, clarifying the risk diffusion pattern of international chip trade and evaluating the impact intensity at each stage are novel research perspectives and important issues that must be urgently investigated. In a shortage scenario, export restrictions between two countries can have a knock-on effect as the tightness of the trade network increases, and negative impacts may spread throughout the network. For this intricate cascade phenomenon triggered by interconnectivity, most scholars often use collective dynamics theory to construct a dynamic network model for simulation and analysis16,17,18. For real networks, Chen et al. developed a natural gas trade crisis propagation model with observable potential trading risks based on an improved bootstrap percolation network model19. Additionally, some studies use variations of the classic SI epidemic model, such as that of Wang et.al., to analyze the potential threat of COVID-19 to global trade in photovoltaic cells20. Literature on cascade failure simulation modeling has recently emerged, covering fields such as mineral21, multimodal transportation22, power23, metabolic24, and food networks25; nonetheless, it has not focused on the chip trade level.

In theoretical networks, some studies have focused on epidemic spread patterns within complex networks with community structures26,27. However, these studies have not accounted for the community’s capacity to digest and absorb risks. In economic discussions on risk management, existing research has underscored the critical role of communities in crisis response28,29. Paveglio et al. observed that communities serve as interactive spheres where members can enhance overall resilience through collaboration and resource mobilization when facing shared risks28. Fowler et al. highlighted that community support and assistance are vital resources for crisis management. Mutual help among community members can alleviate some immediate challenges29. Furthermore, the attenuation effects of propagation and the degree of trade dependency between economies are critical factors that should not be overlooked in the study of supply risk propagation. In response to supply risks, governments and relevant institutions typically implement a series of proactive measures, such as seeking alternative supply solutions and establishing strategic reserves, which drive the adjustment and evolution of risks towards mitigation30,31. According to resource dependence theory, if a country becomes reliant on a particular resource, policy changes and other fluctuations in the resource-supplying country will impact the dependent country’s import and trade structure32. However, existing research has yet to incorporate these factors into the design of cascading propagation mechanisms for supply risk.

This study aims to address research gaps in three critical areas. The primary research objectives are as follows: First, we abstract global chip trade relationship data from 2009 to 2021 into multiple asymmetrically directed weighted networks, thoroughly analyzing the evolution of international chip trade, including its trends and driving factors. By employing macro-network and micro-node indicators such as network density, reciprocity, and less commonly used in/out-eigenvector centrality, we precisely unearth the structural characteristics of the international chip trade networks and their evolutionary trajectories. Second, based on the linear threshold model, we propose two improved risk cascading propagation models driven by node failure and edge restraint, further innovatively opening the research paradigm of focused-edge networks. Third, by incorporating the community’s capacity to digest and absorb risks, we introduce a community infection-driven cascading risk propagation mechanism, which accounts for the effects of propagation attenuation and the degree of trade dependency. These multi-dimensional dynamic perspectives provide insights into network structure changes and propagation abilities of priority countries, thereby identifying potential time-varying risks in the chip trade. Finally, based on the main conclusions, scientific decision-making bases are provided to develop the global chip industry and prevent trade risks. We also discuss some prospects for future research.

Methods

Data sources

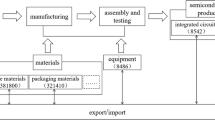

The Centre for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), a US think tank, released a policy brief in 2021 titled ‘Securing the Semiconductor Supply Chain’1. The global chip trade data used in this report are derived from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade), HS code 8542. Based on authoritative data, this study sequentially constructs international chip trade networks from 2009 to 2021. To standardize the range of the selected targets, this study screens only countries and regions with ISO codes involving 232 research objects. The scale of trade exchanges among the four economies of mainland China, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR, and Taiwan are counted individually to distinguish their relative importance. Trade volume is measured as a value (USD). Additionally, the same trade flows recorded by UN Comtrade may have asymmetric numerical discrepancies owing to different import and export perspectives, and larger values are retained here to minimize the impact of statistical omission errors.

Network construction

Based on the complex network analysis method, international chip trade flows are abstracted as asymmetric weighted complex networks with the vector \({V_e} = [{v_e}](e = 1,2,...,n)\), which donates chip export countries (or regions), and vector \({V_i} = [{v_i}](i = 1,2,...,m)\), which indicates chip import counties (or regions). The adjacency matrix \(A = [{a_{ei}}](e = 1,2,...,n;i = 1,2,...,m)\) represents the trade relationships between countries (or regions). \({a_{ei}}(t) = 1\) implies that a chip export transaction existed between nodes \(v_e\) and \(v_i\) in year t. Otherwise, \({a_{ei}}(t) = 0\). \(W = [{w_{ei}}](e = 1,2,...,n;i = 1,2,...,m)\) is the chip trade volume matrix between countries (or regions), where element \({w_{ei}}(t)\) represents the sum of the value of chips exported from node \(v_e\) to node \(v_i\) in year t. Therefore, \({a_{ei}}(t) = 1\) when \({w_{ei}}(t) > 0\). The nodes and connected edges form an international chip bilateral trade network, which is \(G = ({V_e},{V_i},A,W)\).

Statistical indicators for analyzing the topological characteristics of international chip trade networks

To further investigate the structural characteristics of the international chip trade networks and their evolutionary laws, this study introduces a complex network topology identification system. The interpretations, significance, and metric formulas are detailed in Table 1.

Risk cascading propagation models driven by node failure, edge restraint and community infection

Independent cascade (LC) and linear threshold (LT) models42 are commonly used to explain risk propagation phenomena in diverse fields from the viewpoint of complex networks. The chip manufacturing industry is capital-, technology-, and talent-intensive, and most countries (or regions) lack the capacity for chip production, relying heavily on trade imports for chip supply and demand. In international chip trade, economies are often influenced by the cumulative impact of multiple import channels. When a shortage shock exceeds their maximum tolerance, it triggers a state change, propagating risks to other export markets. This propagation characteristic aligns closely with the “cumulative impact mechanism, threshold failure criteria, and influence transmission nature” of the linear threshold model42. This paper draws on the LT model’s concepts, defining the influence of trade partners as a reduction in chip supply (\(\alpha \times \text {export value}\)) and introduces the critical indicator of weighted in-degree to measure whether the actual import volume can meet an economy’s basic chip demand (\(\beta \times \text {weighted in-degree}\)), where \(\alpha , \beta \in [0, 1]\). On this basis, this study constructs plausible scenarios better aligned with the reality of the international chip trade. The model assumptions are as follows:

Hypothesis 1: All nodes within the international chip trade network can be assigned two states: normal (N) and abnormal (A). The normal state denotes that the chip trade between countries (or regions) is completed at the rated scale. The abnormal state indicates that a country (or region) being undersupplied with exports owing to the weakened utility of the import channel.

The technological barriers in chip manufacturing are extremely significant, primarily reflected in three aspects: high technical complexity43, substantial capital and long-term investments10, and a highly concentrated and globally dependent supply chain44. These characteristics limit the rate of capacity expansion in the chip industry, making it difficult to swiftly respond to short-term market demand fluctuations. Furthermore, the concentration and dependency determine the complexity and fragility of the supply chain, making reconstruction and recovery exceptionally difficult after disruption. In recent years, the prolonged escalation of trade frictions has impacted the chip industry in various ways, including obstructed cross-border movements45, increased production and operational costs46, challenges of industry and supply chain restructuring47, constraints on technological innovation48, and the unpredictability of market supply and demand14. These factors collectively make the recovery of the chip supply shortages particularly challenging and unlikely to change in a short term (see Supplementary Information S1 for specific impact mechanisms). Based on this, Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: Owing to the high technical barriers to chip manufacturing and festering trade friction, the chip supply shortage is difficult to recover in a short period. Therefore, it is assumed that a country (or region) is in a constant state of abnormality once it becomes a source of risk propagation.

Initially, all nodes in the chip trade network are in a normal state, and the maximum load each node can support is its initial demand, \(S^{in}\).

The following is the specific cascading dynamic model.

(1) Risk cascading propagation driven by node failure

Owing to various unstable factors in the existing international situation, node i is the initial risk source. As shown in Fig. 1, when the trade flows from i to j, k experiences a shock, the trade volumes corresponding to these export links will decrease by a proportion of \(\alpha\). For normal nodes j and k, if the loss of chip imports exceeds their ability to withstand crisis, the state of these nodes also changes, and the change condition depends on Eq. (1).

Here, \(\alpha\) denotes the shock coefficient, \(\beta\) represents the risk resistance coefficient, and t signifies the year of study.

After node j is infected, the risk shock continues to spread to other import markets k and l through the export channels of i and j. Under dual influences, the reduction in the import value of node k continues to grow until the discriminant condition 2 is satisfied.

The scope of the propagation will expand further. Therefore, the cascade terminates when no more failed nodes are added to the trade network. The percentage of abnormal nodes determines the avalanche ratio when node i is the initial risk source.

(2) Risk cascading propagation driven by edge restraint

In recent years, trade sanctions targeting the chip sector have become increasingly frequent, such as the United States’ repeated export controls on Chinese chip companies and its restrictions on advanced chip exports to Russia45,48. Against this background, this paper designs an edge-restraint-driven risk propagation model to investigate how the reduction in unilateral chip trade volume affects system stability. As in Fig. 1, node m is directed against a single link in the initial phase: the trade flow to node n is reduced by \(\alpha\). For a normal node n, if the change in imports exceeds the maximum it can endure, node n becomes a new source of risk propagation.

The risk will continue to spread to \(n's\) export partners, and the subsequent propagation process is similar to the node failure driven risk cascading propagation scenario. where the export value of node n to nodes m , o and p is updated to \((1 - \alpha ){w_{nm}}(t)\), \((1 - \alpha ){w_{no}}(t)\),\((1 - \alpha ){w_{np}}(t)\), respectively. Subsequently, node p becomes anomalous.

Superimposed infected node o:

Until the avalanche is saturated with the number of nodes, the process ends.

(3) Risk cascading propagation driven by community infection

Scenario 1. Considering the effects of propagation attenuation

This study employs the Louvain algorithm49, based on modularity optimization, for community detection, revealing stable clustering structures in international chip trade (see Supplementary Information S1 for further details).

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the specific cascading process is as follows.

Step 1. Upon examination, Community 1 comprises nodes a, b, and c; Community 2 includes nodes d, g, and h; Community 3 consists of nodes e and f.

Step 2. When a community is exposed to risk, the initial spread is confined within the community. The trade volumes from the initial risk source a to b and c are proportionally reduced by a factor of \(\alpha\). For normal nodes b and c, if the loss in chip imports exceeds their risk tolerance ability, the state of these nodes will change, as determined by Eq. (6).

At this point, node c transitions to an abnormal state.

Step 3. A community typically possesses the capacity to coordinate and recover following a shock. However, when the risk carried within the community reaches the limit of its risk absorption capacity, the risk will breach the boundary and begin to spread externally. This critical point is defined as follows:

where c represents the community where the risk source is located. \(N_{\text{ failure } }^c\) denotes the total number of failed nodes within community c, and \(N_{\text{ total } }^c\) represents the total number of nodes within community c. The parameter \(\lambda\) measures the community’s risk absorption capacity, \(\lambda \in [0,1]\).

Upon evaluation, Community 1 satisfies the conditions for outward propagation.

Step 4. The risk will cascade both within and outside of Community 1 simultaneously. Internally, the trade volumes from risk sources a and c to b decrease; externally, the supply from risk sources a and c to e, d, and g also diminishes. Notably, this scenario takes into account the attenuation effects of propagation: as iterations progress, the impact of the risk gradually weakens, expressed as \((\alpha -\gamma n) w(t)\). The parameter \(\gamma\) is the attenuation factor, \(\gamma \in [0,0.01 \alpha ]\), and n is the number of iterations. Taking node d as an example:

Upon evaluation, nodes b, d, e, and g are all determined to be in an abnormal state. Community 2 also acquire the capability for outward propagation.

Step 5. By iterating in this manner, the cascade ceases when no further nodes fail within the trade network.

Scenario 2. Considering the degree of trade dependency

According to Emerson’s definition of dependency50, and drawing on the measurement method of trade dependency based on the “third-party effect” proposed by Liu et al.51, this paper calculates the chip trade dependency of economy i on economy j , denoted as \(T D_{i j}\) (see Supplementary Information S1 for detailed calculation procedures).

The distinction from Scenario 1 lies in this scenario’s methodology: the supply reduction is calculated based on the trade dependency between the risk source and its trade partners, incorporating the amplifying effect of trade dependency on the impact of shocks. The specific calculation formula is:

Here, \(T D_{i j} \in [0,1]\) after interval quantization processing. When there is no trade dependency between economies, the supply reduction is primarily determined by shock coefficient. When trade dependency exists, the supply reduction is positively correlated with the degree of trade dependency between the economies.

Results

Between 2009 and 2021, the boom iteration in information technology has led to a significant increase in the total volume of international chip trade, from USD 448.903 billion to USD 1422.95 billion2, with an average annual growth rate of 16.69%. Three periods can be identified for overall evolutionary patterns (Fig. 2). First, from 2009 to 2012, a low-speed expansion period; second, from 2013 to 2016, a steady development period; third, from 2017 to 2021, a rapid-paced growth period. The global economic (GDP) trend is a crucial factor influencing the semiconductor market’s development. Therefore, the drivers of change during these three periods can be found in the corresponding macroeconomic contexts. The rapid spread of the 2008 financial crisis dealt a severe blow to the world’s economy, and the international chip trade struggled to survive the waves of shocks, with the scale of trade expanding sluggishly. Since 2013, the global economic situation has gradually recovered, and the semiconductor industry has entered a new stage of stabilizing progression after meeting the trend of leaping forward, and the trade environment has improved. Until 2017, the world economic growth rate exceeded 3%, and the semiconductor industry’s total revenue increased by 21.6% year-over-year52. Since then, the chip trade has experienced explosive expansion. In addition, other crucial factors also propelled the evolution of the trade pattern. The primary evolutionary mechanisms at different periods are provided in the Supplementary Information S1.

Evolutionary analysis of topological characteristics in international chip trade networks

Network density and reciprocity

The international chip trade network density and reciprocity values in 2009-2021 are within the ranges of [0.153, 0.168] and [0.610, 0.646], respectively (Fig. 3). Many peripheral economies maintain relatively sparse chip trade links, diminishing their abilities to flow trade products at an aggregate level. Further, to share development opportunities, most economies have aggressively cultivated trading modes conducive to facilitating bilateral cooperation, with a gradual deepening of reciprocal inclinations. Specifically, two distinct phases can be identified in the evolution of network density. First, from 2009 to 2017, denser network connections are typical. In 2017, the recovery of the world economy gained momentum, with numerous countries (or regions) signing free trade agreements, such as the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the ASEAN-Hong Kong Free Trade Agreement. These initiatives aimed to reduce both tariff and non-tariff barriers. While major economies activated endogenous growth drivers, regional cooperation trends intensified, the development potential of foreign chip trade accelerated its release, and network density reached its peak. Second, the broken line indicates a V-shaped trend between 2018 and 2021. The development of network reciprocity can also be divided into two stages. The first is from 2009 to 2015, which fluctuates at a relatively low level. The second is from 2016 to 2021, the values increase noticeably in an N-shaped pattern. The second phase of the development of the two indicators is similar at the time points of 2020 and 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was in its most severe stage, and the efficiency of the logistics system on which the chip production chain relies drastically decreased. A higher degree of risk exposure caused the chip industry to experience cold winters. To reduce external dependencies, enterprises have begun to reconsider their strategies in the chip industry, progressively shifting their strategic focus towards the localization of the industry chain and diversification of the supply chain, thereby diminishing the extent of multinational trade cooperation to a certain degree. In 2021, with the improvement of the pandemic situation, the introduction of incentive semiconductor production policies in many countries encouraged major chip manufacturers to strive to support the chip production chain. Additionally, digital transformation fueled a surge in demand for chips. All these factors have facilitated international trade and economic cooperation.

Average path length and clustering coefficient

From 2009 to 2021, the average path length and clustering coefficient of the international chip trade networks are located in the intervals [1.801, 1.890] and [0.764, 0.808], respectively (Table 2). The number of nodes and links in trade networks has constantly contracted and expanded owing to the alternating recession and recovery of the world business cycle, and the shortest distances between economies have been updated accordingly. Consequently, the average path length tends to oscillate cyclically under the influence of macro situations. Throughout the study period, the indicator generally fluctuated at a low level: exports could readily reach the trade destination through 1.9 pathways, with a maximum of one transit. This ease of access fostered intimate, reciprocal trading relationships. Despite the complicated changes in the external situation, an increase in the network’s overall cohesion was challenging to stop. Comparing the clustering coefficients and average path lengths of the international chip trade networks with the equivalent randomized networks (possessing the same degree distribution), respectively, we obtain the coefficients \(\sigma\)53,

C(L) and \(C_r(L_r)\) are the clustering coefficients (average path lengths) of the chip trade networks and the equivalent randomized networks, respectively. To avoid error, 20 equivalent randomized networks satisfying the real network properties of the same year are generated, and \(\sigma\) is calculated separately to determine the mean \(\bar{\sigma }\). The value of \(\bar{\sigma }\) in 2017 is 2.12-the smallest value of \(\bar{\sigma }\) across all years. The judgment standards are as follows:

Therefore, the international chip trade networks conform to the traits of highly connected and compact small-world networks.

Degree centrality and betweenness centrality

From a holistic viewpoint, this study discusses the evolutionary patterns of the statistical indicators in the top seven core economies in terms of degree centrality and betweenness centrality from 2009 to 2021. The substantial overlap of the research objects in Fig. 4a,b (to ensure a concise presentation of information, the names of the economies shown in following Figs are presented using ISO 3166 codes) implies that economies with influential advantages are more likely to have the radiation function of trade pivots. Mainland China and the US, which dominate in terms of degree centrality, are balanced in power and alternate at the top of the list. China unswervingly promotes reform and opening up in the new era and proposes the Belt and Road Initiative, which opens up a high-quality development path for the comprehensive upgrading of the global semiconductor industry chain. Under favorable policies, China has actively cultivated chip trading ties with ASEAN nations. The expansion of the foreign trade area ranked mainland China’s chip import and export links first globally from 2013 to 2018. In the fields of semiconductor R &D and development, as well as chip design, as the origin of the supply chain of numerous multinational enterprises, the US (the frontrunner) maintains a strong core-technology competence that is difficult to replace. In its most recent annual report, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) disclosed that US manufacturers accounted for approximately 50% of total sales in the global chip market, with exports to 194 countries (or regions)54.

The evolution of degree centrality in some economies has special time points. In 2009, the world’s second-largest DRAM company, Qimonda (Germany), declared bankruptcy owing to a capital chain rupture, resulting in an abrupt decline in German degree centrality in 2010. In 2013, with the prevalence of mobile devices, ARM (UK) seized growth opportunities in the global mobile chip market and exceeded the ceiling on its number of trading partners. The pinnacle of Dutch degree centrality in 2015 was related to the acquisition of Freescale in the US by the Netherlands’ NXP. NXP has since become the world’s largest supplier of automotive semiconductors. Further, some economies’ degree centrality has not been affected by extreme occurrences, such as France, where variations are slight, and Singapore, where it has increased steadily. The trend change in the betweenness centrality and degree centrality of the core economies has a certain homogeneity. The main difference is that the US, because of its superior geographical conditions, plays the role of a sea and land transportation hub and possesses the strongest flow control capability for chip resources. Canada, which fails to reach the top seven in the degree centrality rankings, manages to achieve a relatively efficient transportation junction function.

Weighted degree, eigenvector centrality, and closeness centrality

Using weighted degree is a trustworthy manner of gauging a country’s (or region’s) status in the international chip trade. Asia, the focus area of the global electronics industry and supply chain, possesses tremendous semiconductor foreign trade capacity. The first seven rows of economies presented in Table 3 represent over 85% of the Asian geographic distribution. Over time, mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore have consistently emerged as the top three nations in purchasing chip resources, upholding the tripartite confrontation. When we compare outflow cases, Taiwan has consistently been at the top, while Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea frequently alternate between second and third places. The following explains why mainland China (in-strength) and Taiwan (out-strength) maintain their absolute predominance: China’s manufacturing industry’s high-end intelligent transformation pull-chip demand has witnessed explosive growth. According to IC Insight statistics, mainland China’s chip market reached approximately USD 186.5 billion in 2021. However, the self-sufficiency rate was only 16.7%55, with strong external dependence. In the same year, Taiwan’s chip industry contributed significantly to the export trade, accounting for 34.8% of its total export value56. Two of the world’s largest foundries are located in this region: TSMC and UMC. TSMC manufacturing can satisfy 54% of global market demand.

In a chip trade network, an extremely strong correlation exists between the eigenvector centrality and the weighted degree of trading economies. The top three economies in both rankings are the same for 2009-2021. Moreover, eigenvector centrality is closely related to the significance of trading partners. The major import sources and export markets of the dominant economies are mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, and Vietnam, crucial trading countries (or regions) with powerful import or export strength. The inference is that cooperation among economies with chip foreign trade leadership in Asia has generated a high-level regional trade collaboration pattern. Similarly, the closeness centrality and degree centrality values are relevant. From a cross-sectional perspective, Table 3 lists mainland China, the US, Germany, France, and the UK as the top five economies in terms of in/out-closeness centrality, which have overwhelming superiority in acquiring and delivering chips. This corresponds to the core economies discussed in Fig. 4’s explanation of degree centrality. Regarding the longitudinal view, the distribution of continents on which economies are located reveals that Europe has the most countries at any given time. This suggests that Europe is at the center of the chip trade networks, with the highest trade efficiency compared to other continents.

Evolutionary analysis of risk cascading propagation in international chip trade networks

Dynamic evolution of risk cascading propagation driven by node failure

The critical years for the evolution of international chip trade network patterns are 2009, 2013, 2017, and 2021. Under the node failure scenario, the risk propagation avalanche ratios of these trade networks are provided (Fig. 5). We present only the evolution of the top 30 influential economies because of the limited impact of most risk sources. Typically, the proportion of economies collapsing because of shocks to supply-shortage risk increases progressively with the value of \(\alpha /\beta\). Except for a few economies that can cause near-total failure of the international chip trade, most economies have avalanche ratios of less than 50%. The difference is that, first, when \(\alpha /\beta\) takes the smaller value of three, in 2009 and 2013, the upper limit of the impact scale is less than 30%; in 2017 and 2021, the range of cascading failures can be up to 99% when Taiwan and mainland China are the initial sources of propagation, respectively. Second, when \(\alpha /\beta\) takes the maximum value, the proliferation of chip supply anomalies in the top 20 economies can cause a devastating collapse of the system in 2009, 2013, and 2021, while other risk sources will have a substantially lower probability of continued risk cascading propagation even if they cut off the export channel. In 2017, only 16 economies dominate significantly, and the avalanche ratio falls to approximately zero, with the lowest ranking; consequently, 2017 witnesses the network’s greatest resistance to risk. Third, regarding the inflection point location and the other points’ distribution, in 2013, \(\alpha /\beta\) = 6, 10, and 15 have an evident rightward trend shift. Furthermore, avalanche ratios of at least 0.95 arise the most-the number of risk sources capable of collapsing practically all economies is the largest in any year. In 2021, the avalanche size extremum occurs the least frequently. This happens when the risk sources have a moderate effect on the whole system. In summary, when confronting the dilemma of chip supply shortfalls, the most stable year for the overall trade structure is 2017, followed by 2009, 2021, and 2013. This is consistent with the evolutionary results of the topological characteristics in international chip trade networks.

With a fixed infection threshold of \(\beta = 0.05\), we explore the influence of the increasing percentage of chip export curtailment in key micro-economies on the macro-network cascading failure scale under different time cross-sections (That is, \(\alpha =0.5\). Unless otherwise stated, the following research is based on this set of parameters). Observe Fig. 6, when the avalanche ratio varies with the chosen \(\alpha\) value, the two admit a positive correlation. In all the years, if the initial risk sources supply the chip at half the total value, the trade system can reach the collapse threshold. A striking feature of the evolution over time is the increase in the longest distance between the corresponding X values when all broken lines in the second row of the graphs are first maximized. This phenomenon is caused by the expanding influence of the first two economies and the waning impact of the last three economies. From 2009 to 2021, the major economies with an occurrence frequency of no less than 75% includes ten. Classified according to the trend of ranking fluctuations, the categories of ranking upgrades are mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia. These risk sources have gradually developed into a steady five-polar distribution pattern. The US, the Netherlands, Germany, Singapore, and Japan are in decline. Among them, mainland China and the US have the most evident increases and decreases, respectively, with their positions swapping, representing a shift in the leading power in chip crisis propagation. The region where the major economies with dominant advantages are concentrated has shifted from Europe and America to Asia, with an overall pattern of ‘east rising and west falling’.

In analyzing risk cascading propagation driven by node failure, mainland China has consistently emerged as a prominent country with an unassailable competitive advantage. Therefore, risk propagation paths from 2009 to 2021 are investigated, with mainland China as the initial risk source (Fig. 7 displays the results for the first three iterations only). In 2009, if mainland China’s chip supply to its trading partners shrinks dramatically, the weakening weights of the export channel will transform several markets into anomalies. Among them, Algeria and Brazil, as typical intermediary countries, continue to spread the shortage crisis to another significant source of propagation, the US. These four countries can successively infect 92.14% of normal nodes in the chip trade network. As important hubs to promote the widespread diffusion of risks, major intermediary countries fulfil two essential propagation elements: they are the first to be affected by macroeconomic fluctuations and geopolitical conflicts, and multiple constraints make them more sensitive to chip shortages. Simultaneously, these countries have numerous vulnerable links, making it easy to transfer risk to other economies.

The initial risk sources and the key intermediary countries each have constructed strong ties with their trading partners, allowing the propagation networks to be categorized into three or four communities at all time cross-sections. In the order of iterations, the failure nodes within the different communities are named the first, second, and last rounds of risk sources. The second propagation cycle is driven by multiple risk sources other than the first and last rounds, which are separately dominated by a core intermediary country. The heterogeneity of risk propagation capacity in these intermediaries leads to differences in the scale of failure at different stages. In 2009, the last round of risk sources, the US, will have the strongest influence; therefore, the diffusion proportion of this round is the highest. In all remaining years, the categorized impact effect of the second round of risk sources is more advantageous. Finally, we observe that after the first three propagations, the avalanche ratio can reach more than 90%; this figure increases progressively each year, reaching a maximum of 98.71%. The propagation path diagram evolves toward a denser trend. This suggests that under constant shock and risk resistance coefficients, if mainland China is the initial source of the propagation, it would have an increasing ability to penetrate risk into the entire chip trade system.

Dynamic evolution of risk cascading propagation driven by edge restraint

Rising geopolitical conflict and resource inequality have stimulated many countries to enact chip restrictions45,48. To better understand the vulnerability transmission phenomenon caused by a sharp decline in the export efficiency of a unidirectional link, this study is designed around an edge-restraint-driven cascading propagation scenario. We derive four unweighted directed graphs from the simulation analysis of the international chip trade networks-the focused-edge networks. This is an innovative study. A crisis that reduces the weights on any of the edges in Fig. 8 ripples through the entire chip trade system and causes it to reach the threshold for a catastrophic collapse. The larger and darker nodes in the graph indicate higher outflow link scales for the economies.

In both risk-driven models discussed in this research, all nodes in the edge networks have a strong probability of globally diffusing shortage shocks through crucial trade links, either as an original outbreak or as an indirect transfer. The directed graphs conform to a multi-hub radiation pattern. When not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the average out-degree of the hubs has increased progressively. The involved economies tended to expand their key export channels-their degree of control and spillover effects on the international chip trade have become more pronounced. We define economies with a superior out-degree as critical hubs. The US has consistently maintained unshakable leadership and played a dominant role. Over time, mainland China’s power has been rising. In 2021, mainland China became the most pivotal hub source owing to its unrivaled important edge advantage. In addition to the above economies, the 5–7 sub-critical hubs with outflow links in the range of [15, 50] are significant components of the focused-edge networks, which are also vital for the risk propagation of international chip trade. The overall distribution pattern finally illustrates a ‘two-core dominant, multi-core secondary dominant’ trend. The intersection of all critical and sub-critical economies in these four years includes the US, mainland China, Germany, Singapore, Taiwan, the Netherlands, and Malaysia. Most are consistent with the major economies defined in weighted degree and eigenvector centrality studies.

Dynamic evolution of risk cascading propagation driven by community infection

Study on the impact of parameters \(\lambda\) and \(\gamma\) in the community infection-driven risk propagation model (considering propagation attenuation). Panels (a) and (c) investigate the effects of \(\lambda\) and \(\gamma\) on the network avalanche scale, while Panels (b) and (d) examine community infection status when key risk sources reduce chip exports under critical \(\lambda\) values (study years: 2009, 2021).

In the risk propagation driven by community infection-considering the effects of propagation attenuation mechanism-it involves two core parameters: the community’s risk absorption capacity (\(\lambda\)) and the attenuation factor (\(\gamma\)). Here, we explore the changing characteristics of avalanche scale in the network under different parameter combinations (see Fig. 9a,c). The total avalanche scale exhibits a stepwise decline as \(\lambda\) increases. This indicates that by enhancing internal coordination and response mechanisms, communities can digest and absorb the impact of chip shortages, preserving their inherent functions and structures while effectively reducing the spread and spillover of risks. Moreover, critical thresholds for \(\lambda\) exist. In 2009, when \(\lambda =0.8\), and in 2021, when \(\lambda =0.6\), the chip trade system abruptly transitions to a relatively stable state, demonstrating that appropriate risk management measures within the community can significantly enhance overall security. Consistent with practical patterns, the total avalanche scale decreases as \(\gamma\) increases; however, from \(\gamma =0.01\) onwards, the marginal effect diminishes, with a “saturation effect” evident: in 2009, when \(\gamma >0.03\), and in 2021, when \(\gamma >0.04\), the benefits of further enhancing the attenuation effects in propagation become negligible.

Next, the critical thresholds of two parameters for different years are selected (in 2009, \(\gamma =0.01\), \(\lambda =0.1, 0.8, 1\); in 2021, \(\gamma =0.01\), \(\lambda =0.1, 0.6, 1\)) to explore the infection status within communities when key risk sources reduce chip exports (Fig. 9b,d). In this study, the internal failure nodes at the point when a community first reaches the condition for outward propagation are termed the “initial risk cluster”, where the outer ring of the pie chart represents the final avalanche scale of the community, and the inner ring reflects the ratios of the initial risk cluster, other failure nodes, and the network avalanche scale. When \(\gamma =0.01\) and \(\lambda =0.1\), compared to other parameters, the initial risk cluster has the smallest size but the strongest infection capability, making the system exceptionally sensitive to the local disturbances caused by the initial risk cluster. Identify the communities where the key initial risk sources are located, it can be observed that in 2009, Communities 1 and 2, and in 2021, Communities 1 and 3, contain several core economies whose failures would trigger a systemic collapse in the international chip trade. Among the most notable examples are Malaysia within Community 2 in 2009, mainland China within Community 1 in 2021, and USA within Community 3 in 2021, which are not only significant risk sources within their communities but also, through trade links with important propagation sources in other communities, lead to the highest initial risk cluster scales across all communities, demonstrating a powerful cross-community impact.

Research exploring the dominant economies and risk propagation paths in the community infection-driven risk propagation model (considering trade dependency). Panels (a) and (c) depict the top ten economies by weighted degree in the chip trade dependency networks, while Panels (b) and (d) illustrate the risk propagation paths within and outside the community when mainland China is the initial risk source (study years: 2009, 2021; the sequence of node failures is color-coded as red, yellow, pink, green, and blue).

Construct the chip trade dependency networks, where the nodes represent the economies involved in trade and the edges represent the trade dependency relationships between these economies, with the edge weights reflecting the degree of trade dependency. In these dependency networks, the top ten economies by weighted degree are shown in Fig. 10a,c. In the simulation results of risk propagation driven by community infection-considering the degree of trade dependency-the top ten risk sources intersect with the aforementioned economies as follows: 2009: mainland China, France, South Korea, Netherlands, Philippines, USA; 2021: mainland China, Germany, Hong Kong, Israel, Singapore, USA. This indicates that economies with high chip trade dependency facilitate the rapid propagation of supply risks through their tight trade connections, and the impact intensity amplifies with the closeness degree of these connections, increasing the system’s vulnerability to external shocks. Figure 10b,d illustrate the risk propagation paths within and outside communities when mainland China serves as the initial risk source, with the parameter \(\lambda\) set at 0.1. Figure 10b corresponds sequentially to Communities 1, 2, and 3 from left to right, while Fig. 10d corresponds to Communities 1, 2, 3, and 4. Should mainland China reduce its chip supply, the risk initially propagates within the community. Once the community’s absorption capacity is exceeded, the risk diffuses both internally and externally. In the first two iterations, mainland China plays a pivotal role in driving the risk propagation, with the proportion of affected economies reaching 97.17% in 2009 and 95.04% in 2021. Notably, all communities, except for Community 1, reach their risk-carrying capacity thresholds by the second iteration, demonstrating their limited ability to digest and absorb risks, thereby rendering them ineffective in managing the internal accumulating risks. Furthermore, most economies within these communities collapse during the second or third iteration. For instance, in Community 2-the largest community-driven by key intermediary countries such as Austria, the avalanche scale during the third iteration exceeds half, reaching 53.93% in 2009 and 50.38% in 2021. This reveals that, under this mechanism, when mainland China is the initial risk source, the risk tends to escalate rapidly within a short period and spread with significant momentum.

Discussion

Amid the prosperity of the chip trade, the adjustment and restructuring of the global industry and supply chain under multiple shocks have increased the uncertainty factors that restrict stable development. In this context, this study addresses research gaps in three critical areas: First, it constructs international chip trade networks from 2009 to 2021 using a complex network approach, providing an in-depth analysis of the evolution mechanisms of chip trade. Based on this, four macro-network and eight micro-node indices are examined to understand the multi-dimensional dynamic evolution of the chip trade. Second, models of risk cascading propagation driven by node failure and edge restraint are proposed, innovatively opening the research paradigm of focused-edge networks. Third, it introduces a risk cascading propagation mechanism driven by community infection, incorporating community risk absorption capacity while considering both the attenuation effects of propagation and the degree of trade dependency. These approaches offer theoretical support for critical issues such as changes in network structure and the influence of key countries. Additionally, the study enhances the robustness of cascade failure analyses within theoretical networks when applied to real-world, complex multi-community structures and multi-dimensional risks. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Topological characteristics in international chip trade networks

Economies are more inclined to deepen their two-way trade flows to seek common developments in the chip industry. The global chip trade structure continues to be optimized, and the scale of foreign trade has surged to new highs. Generally, the international chip trade networks are highly connected and cohesive, consistent with their small-world characteristics. mainland China and the US alternately lead foreign trade. When the links are weighted, mainland China (in-strength) and Taiwan (out-strength) exhibit unparalleled dominance. From a regional perspective, the development of the chip trade in Asia, Europe and America has unique characteristics. In Asia, the leading economies in chip foreign trade have jointly opened up a high-level regional collaboration pattern with the goal of mutual benefit and a win-win situation. Mainland China, the US, Germany, France, and the UK, most of which are located in Europe and America, are less susceptible to control and are more efficient at acquiring and transferring chips.

(2) Risk cascading propagation in international chip trade networks

The structural stability of international chip trade for all years is ranked as \(\mathrm{{ 2017> 2009}} \approx \mathrm{{2021 > 2013}}\). When fixing the infection threshold, \(\beta\) , the percentage of chip shrinkage in key microeconomies is positively correlated with the avalanche ratio. Observing the developments in the magnitude of these economies’ effects on international trade, mainland China’s capacity for risk penetration has substantially increased, resulting in a switch in status between mainland China and the US. The dominant force in crisis propagation has gradually shifted from Europe and America to Asia, with the general trend of ‘east rising and west falling’. There is a universal feature in the development of focused-edge networks that conform to a multi-hub radiation pattern. The important hubs include the US, mainland China, Germany, Singapore, Taiwan, the Netherlands, and Malaysia. The evolutionary difference lies in the fact that, excluding the impact of COVID-19, the average out-degree of hubs has an upward trend, revealing that the degree of control and spillover effects of the focal risk sources on the international chip trade are increasing progressively. In risk propagation driven by community infection, an increase in absorption capacity \(\lambda\) or attenuation factor \(\gamma\) consistently leads to a decline in avalanche scale, with \(\lambda\) displaying critical thresholds. Economies highly dependent on chip trade facilitate the spread of supply shortage risks through close trade connections, while the amplification effects of dependence degree exacerbate the system’s vulnerability to external shocks.

Thus, the following policy recommendations are proposed for the high-quality development and risk prevention of the international chip trade: (1) Economies should positively enhance self-dependent innovation in digital core technology and strengthen chip R &D and production capabilities. Simultaneously, they can grasp favorable opportunities, explore new advantages in open economy development, and excavate potential and efficient business markets. (2) To promote development, economies should continue to provide financial and technical support for constructing infrastructure, such as railroad transportation systems and port logistics, within their borders, opening up channels for unimpeded trade in chips for economies with lower levels of cooperation to enhance the overall international chip trade transportation efficiency. (3) Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia-the key risk sources in the above node failure scenarios-must formulate sophisticated risk prevention measures to improve risk resistance capacity through real-time monitoring of changes in the international situation and chip trade patterns. They should also reserve resources in advance and expand purchasing channels to ensure the chip supply chain’s stable operation. (4) The US, mainland China, Germany, Singapore, Taiwan, the Netherlands, and Malaysia, the hub economies involved in these focused-edge networks, must emphasize optimizing the structure of their chip exports and should be even more deliberate in introducing chip restrictive policies for their important partners, ensuring that the outflow link weights do not fall below the market side demand thresholds; otherwise, the shortfall crisis may seriously threaten the stability of the trade system. (5) In international chip trade, economies within the same community should establish robust cooperative mechanisms to enhance internal information sharing and resource integration, effectively curbing the outward spread of supply risks and preventing broader systemic impacts. Additionally, economies should diversify their trade partners, reducing reliance on a single partner or market, thereby dispersing risks to ensure stable development amid global supply fluctuations.

Future research will concentrate on international chip supply networks at the micro-firm level. Firms can self-adaptively reconstruct their cooperation models in response to shocks, allowing us to gain insights into whether the adjustment reduces the impact of risks on the chip supply networks. Additionally, it is feasible to introduce an empirical econometric model to investigate the crucial factors affecting the progress of the international chip trade and further explore the linkage effects of changes in chip trade structure on other industries. Thus, research horizons can be continuously enriched.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed to support the outcomes of this study are available online at https://github.com/shilei65/Data-for-international-chip-trade-network-.git.

Change history

15 October 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75856-6

References

Khan, S. M., Mann, A. & Peterson, D. The semiconductor supply chain: Assessing national competitiveness. Center for Security and Emerging Technology 8 (2021).

Un comtrade database (2021). [Online; accessed 14-March-2022].

Hosoe, N. Impact of tighter controls on Japanese chemical exports to Korea. Econ. Model. 94, 631–648 (2021).

Luo, Y. & Van Assche, A. The rise of techno-geopolitical uncertainty: Implications of the united states chips and science act. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1, 1–18 (2023).

Cha, V. D. Collective resilience: Deterring china’s weaponization of economic interdependence. Int. Secur. 48, 91–124 (2023).

Hohenstein, N.-O. Supply chain risk management in the covid-19 pandemic: strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service providers’ performance. Int. J. Log. Manag. 33, 1336–1365 (2022).

Ochonogor, K. N., Osho, G. S., Anoka, C. O. & Ojumu, O. The covid-19 pandemic and supply chain disruption: An analysis of the semiconductor industry’s resilience. Int. J. Tech. Sci. Res. Eng. 6, 7–18 (2023).

Isik, O., Inadagbo, K., Bulbul, Y., Isik, M. & Dikmen, C. International chip crisis: Country approaches. In Proceedings of IConSES (2023).

Gereffi, G., Lim, H.-C. & Lee, J. Trade policies, firm strategies, and adaptive reconfigurations of global value chains. J. Int. Bus. Policy 1, 1–17 (2021).

Wu, X., Zhang, C. & Du, W. An analysis on the crisis of “chips shortage’’ in automobile industry—based on the double influence of covid-19 and trade friction. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 1971, 012100 (2021).

Moreno, Y. & Perc, M. Focus on multilayer networks. N. J. Phys. 22, 1 (2020).

Duan, D. & Du, D. Structural evolution of global high-tech trade system: Products, networks and influencing factors. Acta Geogr. Sin. 75, 227–244 (2020).

Ren, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, Y. & Liu, Y. Dynamics of the global semiconductor trade and its dependencies. J. Geog. Sci. 33, 1141–1160 (2023).

Ramani, V., Ghosh, D. & Sodhi, M. S. Understanding systemic disruption from the covid-19-induced semiconductor shortage for the auto industry. Omega 113, 102720 (2022).

Mohammad, W., Elomri, A. & Kerbache, L. The global semiconductor chip shortage: Causes, implications, and potential remedies. IFAC-PapersOnLine 55, 476–483 (2022).

Lee, K.-M. et al. Impact of the topology of global macroeconomic network on the spreading of economic crises. PloS one 6, e18443 (2011).

Lee, K.-M. & Goh, K.-I. Strength of weak layers in cascading failures on multiplex networks: Case of the international trade network. Sci. Rep. 6, 26346 (2016).

Perc, M. Diffusion dynamics and information spreading in multilayer networks: An overview. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 228, 2351–2355 (2019).

Chen, Z., An, H., An, F., Guan, Q. & Hao, X. Structural risk evaluation of global gas trade by a network-based dynamics simulation model. Energy 159, 457–471 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Trade characteristics, competition patterns and covid-19 related shock propagation in the global solar photovoltaic cell trade. Appl. Energy 290, 116744 (2021).

Sun, X., Shi, Q. & Hao, X. Supply crisis propagation in the global cobalt trade network. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 179, 106035 (2022).

He, Z., Guo, J.-N. & Xu, J.-X. Cascade failure model in multimodal transport network risk propagation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 1–7 (2019).

Guo, H., Yu, S. S., Iu, H. H., Fernando, T. & Zheng, C. A complex network theory analytical approach to power system cascading failure–from a cyber-physical perspective. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 29, 1 (2019).

Smart, A. G., Amaral, L. A. & Ottino, J. M. Cascading failure and robustness in metabolic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 13223–13228 (2008).

Zhou, X.-Y. et al. Influence of Russia-Ukraine war on the global energy and food security. Resour. Conserv. Recycling 188, 106657 (2023).

Zhu, P., Wang, X., Zhi, Q., Ma, J. & Guo, Y. Analysis of epidemic spreading process in multi-communities. Chaos Solitons Fract. 109, 231–237 (2018).

Gao, Z., Gu, Z. & Yang, L. Effects of community connectivity on the spreading process of epidemics. Entropy 25, 849 (2023).

Paveglio, T. B., Boyd, A. D. & Carroll, M. S. Re-conceptualizing community in risk research. J. Risk Res. 20, 931–951 (2017).

Fowler, K. & Etchegary, H. Economic crisis and social capital: The story of two rural fishing communities. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 81, 319–341 (2008).

Hammi, B., Zeadally, S. & Nebhen, J. Security threats, countermeasures, and challenges of digital supply chains. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–40 (2023).

Garnett, P., Doherty, B. & Heron, T. Vulnerability of the united kingdom’s food supply chains exposed by covid-19. Nature Food 1, 315–318 (2020).

Yiran, Z. et al. The impact of structural changes of trade dependence network on cobalt price from the perspective of industrial chain. Resour. Sci. 44, 1344–1357 (2022).

Fischer, C. S. & Shavit, Y. National differences in network density: Israel and the united states. Soc. Netw. 17, 129–145 (1995).

Chaney, T. The network structure of international trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 3600–3634 (2014).

Barrat, A., Barthelemy, M., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 3747–3752 (2004).

Fagiolo, G. Clustering in complex directed networks. Phys. Rev. E 76, 026107 (2007).

Freeman, L. C. et al. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social network: critical concepts in sociology. Londres: Routledge 1, 238–263 (2002).

Newman, M., Barabási, A.-L. & Watts, D. J. The structure and dynamics of networks (Princeton university press, 2011).

Freeman, L. C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 1, 35–41 (1977).

Müller, B., Reinhardt, J. & Strickland, M. T. Neural networks: An introduction (Springer Science & Business Media, 1995).

Wasserman, S. & Faust, K. Social network analysis: Methods and applications (Cambridge university press, 1994).

Kempe, D., Kleinberg, J. & Tardos, É. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network. In Proceedings of the ninth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, pp. 137–146 (2003).

Aboagye, A., Burkacky, O., Mahindroo, A. & Wiseman, B. When the chips are down: How the semiconductor industry is dealing with a worldwide shortage. In World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/semiconductor-chip-shortage-supply-chain (2022).

Woods, D. & Gajjar, D. Supply of semiconductor chips. POSTnote 721, Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (2024).

Shivakumar, S., Wessner, C. & Howell, T. Balancing the ledger: Export controls on us chip technology to china. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/balancing-ledger-export-controls-us-chip-technology-china (2024).

Xiao, Y. The impact of the us-china trade war on china’s semiconductor industry. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Financial Management and Economic Transition (FMET 2022), 665–677 (Atlantis Press, 2022).

Chakraborty, A. Global semiconductor shortage triggering obstructions and production delays. Glob. J. Bus. Integral Secur. (2016).

Kaur, D. Cisco ceo - global chip shortage to last for most of this year - techhq (2021). Accessed: 2024-06-03.

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R. & Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech: Theory Exp. 2008, P10008 (2008).

Emerson, R. M. Power-dependence relations. In Power in modern societies, pp. 48–58 (Routledge, 2019).

Liu, L.-Q., Yan, X.-F., Yang, L.-S. & Song, M. Research on the evolution and endogenous mechanism of the international trade dependence network. China Ind. Econ. 1:98–116. https://doi.org/10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2021.02.015 (2021).

Annual semiconductor sales increase 21.6 percent, top $400 billion for first time (2018). [Online; accessed 21-May-2022].

Humphries, M. D., Gurney, K. & Prescott, T. J. The brainstem reticular formation is a small-world, not scale-free, network. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 273, 503–511 (2006).

Sia factbook 2022 (2022). [Online; accessed 1-March-2023].

The 2022 mcclean report (2022). [Online; accessed 21-March-2023].

Taiwan ministry of finance (2022). [Online; accessed 21-May-2022].

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support provided to L.S. by the Major Program of the National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China (Grants Nos. 22 &ZD158 and 22VRCO49). L.S. also received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11931015 and 12271471).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.: conceptualization, software, formal analysis, writing—original draft. C.D.: conceptualization, data curation. L.S.: writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Lei Shi was incorrectly affiliated with ‘School of Economics, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian 116025, Liaoning, China.’ Their correct affiliations are listed in the correction notice.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Du, C. & Shi, L. Establishing the robustness of chip trade networks by dynamically considering topology and risk cascading propagation. Sci Rep 14, 20687 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71345-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71345-y