Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the related factors linked to the development and infectivity of tuberculosis. This was achieved by comparing the clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) who tested positive in smear Mycobacterium tuberculosis tests with this who tested negative in smear mycobacterium tests but positive in sputum Gene Xpert tests. We gathered clinical data of 1612 recently hospitalized patients diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis who tested positive either in sputum Gene-Xpert test or sputum smear Mycobacterium tuberculosis tests. The data was collected from January 1, 2018 to August 5, 2023, at Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital. We conducted separately analyzes and comparisons of the clinical characteristics between the two groups of patients, aiming to discussed the related factors influencing the development and infectivity of tuberculosis. In comparison to the GeneXpert positive group, the sputum smear positive group exhibited a higher proportion of elderly patients (aged 75–89) and individuals classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2). Furthermore, this group was more prone to experiencing symptoms such as weight loss, coughing and sputum production, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, and difficulty breathing. Moreover, they are also more likely to develop extrapulmonary tuberculosis, such as tuberculous meningitis, tuberculous pleurisy, and tuberculous peritonitis. These clinical features, when present, not only increase the likelihood of a positive result in sputum smear tests but also suggest a high infectivity of pulmonary tuberculosis. Elderly individuals (aged 75 to 89) who are underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), display symptom of cough, expectoration, hemoptysis and dyspnea-particularly cough and expectoration-and those with extra pulmonary tuberculosis serve as indicators of highly infectious pulmonary tuberculosis patients. These patients may present with more severe condition, carrying a higher bacteria, and being more prone to bacterial elimination. Identification of these patients is crucial, and prompt actions such as timely and rapid isolation measures, cutting off transmission routes, and early empirical treatment of tuberculosis are essential to control the development of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease. In 2022, tuberculosis stands as the second leading cause of death from a single source of infection, surpassing only by coronavirus (COVID-19). The estimated number of individuals affected by tuberculosis in 2022 is 20.6 million, surpassing the figures of 10.3 million in 2021 and 10 million in 2020. Additionally, about 7.5 million new diagnoses are anticipated in 2022, surpassing the figures of 5.8 million in 2020 and 6.4 million in 2021. The global incidence rate of tuberculosis is expected to increase by 3.9% between 2020 and 2022, reversing the trend of an annual decline of about 2% observed over the past 20 years1,2.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), which spreads when patients release bacteria into the air, such as during coughing. It is estimated that approximately a quarter of the world’s population, nearly 2 billion people, are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis3.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Stop tuberculosis Strategy mandates a yearly reduction of 10% in the tuberculosis incidence rate by 2025. An integral aspect of this strategy is the attainment of swift detection and early diagnosis of tuberculosis. Currently, the conventional methods for detecting tuberculosis include microscopic smear examination, culture, drug sensitivity test and chest X-ray examination. Among these methods, the culture and drug sensitivity test for tuberculosis bacteria are the gold standard for diagnosing tuberculosis, with microscopic examination of sputum smear being a crucial diagnostic method. While a positive result in sputum smear indicates high infectiousness, its sensitivity is low4. Gene Xpert, a rapid detection method for Mycobacterium tuberculosis recommended by the WHO, is based on real-time PCR detection and molecular technology. This method boasts high sensitivity, accuracy and speed (results obtainable within 2 h). Importantly, it can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis even when the sputum smear results are negative. This capability aids in the early intervention of tuberculosis patients, preventing severe consequences and delaying the optimal treatment of patients5.

While some literatures reported on the clinical characteristics of patients with positive Gene Xpert test and positive sputum smear test6,7,8,9,10,11, few articles have conducted a comparative analysis of these characteristics. This scarcity of comparative studies limits the understanding of the clinical features and associated factors related to the development and infectivity of tuberculosis in patients who tested positive in smear Mycobacterium tuberculosis tests compared with those who tested negative in smear mycobacterium tests but positive in sputum Gene Xpert tests. To address this, we analyzed the data of hospitalized patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis to understand the clinical characteristics of Gene Xpert positive and sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients. As with smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients can directly discharge Mycobacterium tuberculosis into the air through coughing, leading to the potential infection of others and further spread, they are considered highly infectious12.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study on hospitalized patients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis at Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital from January 1, 2018 to August 5, 2023. Data for this study were collected from patients’ hospitalization medical records and anonymized for analysis. All methods were carried out comply with the ethical standards of Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, as well as the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All clinical data and laboratory results, as well as the waiver of patient informed consent has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Sichuan Provincial Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Protocol 20220-254).

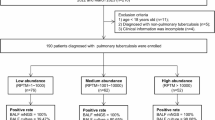

In accordance with the diagnostic criteria for pulmonary tuberculosis outlined in the Health Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China (ws 288-2017), the inclusion criteria are as follows: (a) confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis through bacteriology (sputum smear); (b) Confirmation of Pulmonary tuberculosis through polymerase chain reaction in respiratory specimens (sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid). The exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) previous diagnosis or treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis; (b) presence of human immunodeficiency virus infection, undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, potential malignant tumors, or concurrent lung diseases (including lung cancer, pneumoconiosis, or other lung infections). Details of the inclusion and exclusion data are presented in Fig. 1.

Parameter collection

Clinical information for all patients encompasses gender, age, nationality, BMI, smoking history, drinking history, and clinical symptoms (cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, night sweats, fever, tightness of breath, dyspnea, etc.). Additionally, extrapulmonary tuberculosis status (tuberculous pleurisy, tuberculous peritonitis, intestinal tuberculosis, joint tuberculosis, urinary tuberculosis, etc.). And other concurrent disease conditions (diabetes, hypertension, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, malnutrition, etc.) are also included in the data collection.

Patients grouping

-

Based on their body mass index (BMI): underweight:BMI below 18.5; normal weight:BMI between 18.5 and 24.9; overweight: BMI great than or equal to 2513.

-

Age groups: Minors: 0–17 years old; Young adults: 18–44 years old; Middle-aged individuals:45–59 years old; Young and elderly individuals: 60–74 years old; Elderly individuals:75–89 years old; Individuals over 90 years old.

-

According to the diagnostic criteria of pulmonary tuberculosis: “Smear negative but geneXpert positive” groups; “Sputum smear positive” group.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted on the clinical data collected from all GeneXpert positive and sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis inpatients. Frequencies and percentages were calculated, and odds ratios (OR) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined to elucidate the correlation between variables. The independent sample T test was employed to assess differences in the distribution of demographic characteristics between the two groups. The chi-square test was used for comparing categorical variables, and univariate and multivariable binary logistic regression (reverse stepwise logistic regression) were employed to identify important variables affecting the incidence and infectivity of tuberculosis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26 software, with a P-value threshold set at 0.05.

Results

Baseline feature comparison

The study reviewed data from 2514 hospitalized patients suspected of pulmonary tuberculosis. A total of 1612 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis were included, with 1180 in the “sputum smear negative but GeneXpert positive” group and 432 in the “sputum smear positive” group. Table 1 and Fig. 2 summarize the clinical characteristics of the two groups of patients.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of gender, ethnicity, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, blood lipids, etc. (P > 0.05). However, a statistically significant difference was observed in age stratification (p < 0.001) and BMI stratification (P < 0.01). The sputum smear positive group exhibited symptoms such as cough, sputum (72.5% vs. 56.4%, P < 0.001), hemoptysis (13.2% vs. 9.5%, P < 0.05), shortness of breath, difficulty breathing (26.2% vs. 21.4%, P < 0.05), and weight loss (37.5% vs. 32.6%, P < 0.05).

The proportion of tuberculosis meningitis (3.7% vs. 1.3%, P < 0.05), tuberculous pleurisy (8.1% vs. 2.7%, P < 0.001), and tuberculous peritonitis (4.4% vs. 0.9%, P < 0.001) was higher in the sputum smear positive group. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed according to the Health Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China—Guidelines for the Classification of Tuberculosis issued by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the two groups of patients in terms of other clinical symptoms, other pulmonary tuberculosis, and other diseases, except for those mentioned above.

Characteristics of related factors in sputum smear positive patients

Patients with positive sputum smear are associated with higher infectivity. We included important variables in the binary regression model and summarized the risk of TB infectivity for these variables (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Compared with patients in other age groups, elderly patients aged 75–89 (multivariate analysis: OR 2.199; 95% CI 1.087–4.446; p < 0.05) are more likely to develop infectivity. Patients with weight loss (p < 0.05), compared with those of normal weight and obese patients, have a higher risk of infectivity. Patients with cough and sputum symptoms (multivariate analysis: OR 1.943; 95% CI 1.513–2.494; p < 0.001) or concomitant tuberculous pleurisy (multivariate analysis: OR 2.968; 95% CI 1.388–6.349; p < 0.01) have an increased risk of infectivity. These factors are significant in both univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

Hemoptysis (univariate analysis: OR 1.449; 95% CI 1.032–2.036; p < 0.05), shortness of breath, difficulty breathing (univariate analysis: OR 1.394; 95% CI 1.010–1.685; p < 0.05), concomitant tuberculous meningitis (univariate analysis: OR 2.987; 95% CI 1.464–6.096; p < 0.05), and concomitant tuberculous peritonitis (univariate analysis: OR 5.107; 95% CI 2.355–11.073; p < 0.05) also increase the risk of infectivity. Tuberculous peritonitis is significant in univariate logistic regression but not in multivariate logistic regression.

Discussion

In our study, elderly patients aged 75 to 89, when compared with patients in other age groups (multivariate analysis: OR 2.199; 95% CI 1.087–4.446; p < 0.05), were found to be more likely to excrete bacteria and develop infectivity. This association may be attributed to factors such as decreased lung function, immune aging, inflammation, lack of appropriate diagnostic/intervention measures, and age-related comorbidities. In most elderly cases, the reactivation of latent pulmonary tuberculosis is prevalent, primarily caused by declining immunity associated with aging. Age-related complications often mask the disease, extending the time to diagnosis. The symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis in the elderly are generally atypical, making early identification challenging14. By the time of diagnosis, the disease may have advanced, leading to a significant increase in sputum bacteria and higher likelihood of infectivity. Moreover, as the only approved tuberculosis vaccine, the BCG vaccine, its effectiveness tends to decrease with age15, which could be another contributing factor to the elevated risk of infectivity in the 75 to 89 year-old group. Therefore, in clinical practice, it is essential to pay attention to pulmonary tuberculosis patients aged 75 to 89 with atypical clinical symptoms to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, ultimately preventing high infectivity.

Our study reveals that the sputum smear positive group exhibits a lower average BMI, is more susceptible to symptoms of weight loss, and has a higher prevalence of individuals classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m)2). Compared to the high sensitivity of GeneXpert detection, the positive rate of sputum smear detection for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is lower16. Generally, patients who test positive on sputum smear are highly infectious, and their condition is often severe. Mild cases may have a lower bacterial count, resulting in negative sputum smear results. As tuberculosis is a chronic wasting disease, severe patients commonly experience weight loss and emaciation. Additionally, various diseases associated with low weight (malnutrition, late HIV) are also more susceptible for tuberculosis17,18,19. Our research indicates that being underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m)2 is helpful for identifying highly infectious pulmonary tuberculosis patients early, enabling timely and rapid isolation measures and the interruption of transmission routes.

However, the correlation between BMI and the prognosis of pulmonary tuberculosis patients is currently unclear, and our future research will delve into these aspects. In clinical practice, when dealing with symptomatic pulmonary tuberculosis patients and awaiting final bacteriological test results, doctors often initiate empirical treatment. Therefore, when clinicians need to make empirical treatment decisions for high-risk tuberculosis patients, considering routine BMI assessment initially, awaiting bacteriological test results, and implementing isolation measures could be a prudent approach.

In our study, individuals with positive sputum smears exhibited a higher likelihood of coughing, coughing (p < 0.001), shortness of breath, difficulty breathing (p < 0.05), and hemoptysis (p < 0.05). Coughing and expectoration are early prominent symptoms of respiratory tract infections, physiologically aiding in clearing and protecting the respiratory tract. However, in patients with tuberculosis, coughing can expel TB bacilli from cavities, consolidation areas and airway mucus, making it easier to detect TB bacilli in sputum smears20. Some studies have reported that compared with smear-negative TB, the proportion of patients with cough is higher among smear-positive patients, and the frequency of sputum cough is also higher21,22,23. Studies have shown that smear-negative patients may have no respiratory symptoms or mild respiratory symptoms24.

When pulmonary tuberculosis patients experience difficulty in breathing, it often indicates that their tuberculosis infection is severe or that corresponding complications have occurred, such as caseous necrosis, scar repair, chronic pulmonary heart disease, etc. Additionally, if concurrent with tuberculous pleurisy, it can cause a large amount of pleural effusion to compress lung tissue, leading to atelectasis and respiratory distress25. At this time, the condition is severe, with a significant increase in tuberculosis bacteria in the body and noticeable respiratory symptoms. A large quantity of bacteria is excreted from the respiratory tract, increasing infectivity. In tuberculosis patients, hemoptysis happens mainly because severe inflammation caused by active disease and bacterial growth. This can damage blood vessels and lead to bleeding24. A recent study shows that the best predictors of high PTB infectivity (AFB +) are hemoptysis (OR = 4.33), cough (OR = 3.00), dyspnea (OR = 2.89)26. Consistent with this, our study also demonstrates that cough, expectoration, tightness of breath, dyspnea, and hemoptysis are factors predicting the high infectivity of tuberculosis.

Our study reveals that individuals with positive sputum smears are more likely to develop tuberculous meningitis (p < 0.01), tuberculous pleurisy (p < 0.001), and tuberculous peritonitis (p < 0.001) compared to the GeneXpert positive group. A large-scale multicenter observational study on the epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis demonstrated that the most common type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is tuberculous pleurisy, and the most common complication of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is tuberculous pleurisy combined with tuberculous peritonitis2. Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most severe manifestation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, with a high patient mortality rate and a high incidence of survivor sequelae27.

In most cases, tuberculosis originates in the lungs and spreads through the respiratory tract. When the body’s immunity is weakened, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can disseminate in lymph or blood, invading organs other than the lungs (except teeth, hair, and nails), leading to extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis may spread outside the lungs through three transmission mechanisms: (1) Mycobacterium tuberculosis initially infects a large number of alveolar macrophages, which are transported and disseminated as these macrophages enter and exit the lymphatic and circulatory systems. (2) Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly infects the epithelial cells that make up the lung barrier, translocating between these cells without damaging the epithelium, or inducing cell death to cause barrier rupture. Dendritic cells that sample antigens in alveoli can transport Mycobacterium tuberculosis to lymph nodes28. Therefore, patients with weakened physical resistance are usually accompanied by extrapulmonary tuberculosis, which is more severe, carries more bacteria, and is easier to excrete bacteria, resulting in high infectivity.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, being a cross-sectional study, while sputum smears have assisted in diagnosing infectious pulmonary tuberculosis compared to Gene X-pert, we cannot establish a causal relationship between age, BMI, and TB contagiousness. Secondly, it is a small sample size, single-center study, emphasizing the need for larger samples and multicenter studies in the future. Additionally, being an observational study, potential selection bias in the research queue may be unavoidable. Thirdly, as the study focuses on tuberculosis patients in southwest China, the generalizability of our results beyond this region may be limited. Last but not the least, although findings demonstrated association between smear/Xpert status and symptoms, the symptoms may be due to comorbidities of TB or increased age.

Conclusions

Our study underscores the heightened susceptibility of elderly individuals with pulmonary tuberculosis aged 75 to 89 to bacterial discharge and contagion, attributable to aging-related factors. A pivotal focus on this demographic in clinical practice is imperative to curb disease progression and enhance contagion control measures. Early identification of underweight individuals (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) proves crucial for promptly recognizing highly infectious pulmonary tuberculosis patients, facilitating swift isolation measures, interrupting transmission routes, and initiating early empirical treatment to curtail disease advancement. Clinical factors like cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, and dyspnea emerge as reliable indicators of heightened tuberculosis infectivity. Furthermore, individuals with compromised physical resistance exhibit a greater propensity for developing extrapulmonary tuberculosis, encompassing tuberculous meningitis, tuberculous pleurisy, and tuberculous peritonitis. In these instances, the condition manifests with increased severity, higher bacterial loads, and a proclivity for bacterial elimination, collectively contributing to elevated infectivity levels.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available concerning students’ privacy and their own or guardian’s willingness but are available from the corresponding author Lan Shang (shanglan8282@163.com) on reasonable request.

References:

Bagcchi, S. WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe 4(1), e20 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in China: A national survey. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 69–77 (2023).

Pagaduan, J. V. & Altawallbeh, G. Chapter Two - Advances in TB testing. In Advances in Clinical Chemistry (ed. Makowski, G. S.) (Elsevier, 2023).

Park, M. & Kon, O. M. Use of Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert ultra in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Expert Rev. Anti Infe. 19(1), 65–77 (2021).

Khadka, P. et al. Diagnosis of tuberculosis from smear-negative presumptive TB cases using Xpert MTB/Rif assay: A cross-sectional study from Nepal. BMC Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4728-2 (2019).

Courtney, H. et al. Prompt recognition of infectious pulmonary tuberculosis is critical to achieving elimination goals: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 7(1), e521 (2020).

Gül ^, Akalın Karaca, E. S., Özgün Niksarlıoğlu, E. Y., Çınarka, H. & Uysal, M. A. Coexistence of tuberculosis and COVID-19 pneumonia: A presentation of 16 patients from Turkey with their clinical features. Tuberk Torak 70(1), 8–14 (2022).

Selmane, S. & L’Hadj, M. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of tuberculosis in leon bernard tuberculosis unit in algeria. Int. J. Mycobact. 9(3), 254 (2020).

Makambwa, E. et al. Clinical characteristics that portend a positive xpert ultra test result in patients with pleural tuberculosis. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 25(2), 42 (2019).

Mantefardo, B., Sisay, G. & Awlachew, E. Assessment of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis and associated factors among patients visiting health facilities of Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2023, 1–7 (2023).

Metaferia, Y., Seid, A., Fenta, G. M. & Gebretsadik, D. Assessment of extrapulmonary tuberculosis using gene xpert MTB/RIF assay and fluorescent microscopy and its risk factors at dessie referral hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 1–10 (2018).

Fennelly, K. P. What is in a cough?. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 5, S51 (2016).

Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995(854):1–452.

Coffman, J. et al. Tuberculosis among older adults in Zambia: Burden and characteristics among a neglected group. Bmc Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4836-0 (2017).

Shahrear, S. & Abmm, I. Modeling of MT. P495, an mRNA-based vaccine against the phosphate-binding protein PstS1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Divers. 27(4), 1613–1632 (2023).

Lee, H. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay as a substitute for smear microscopy in an intermediate-burden setting. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care 199(6), 784–794 (2019).

Ockenga, J. et al. Tuberculosis and malnutrition: The European perspective. Clin. Nutr. 42(4), 486–492 (2023).

Menon, S. et al. Convergence of a diabetes mellitus, protein energy malnutrition, and TB epidemic: The neglected elderly population. BMC Infect. Dis https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1718-5 (2016).

Park, J. et al. Association of duration of undernutrition with occurrence of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14876-1 (2022).

Turner, R. D. Cough in pulmonary tuberculosis: Existing knowledge and general insights. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 55, 89–94 (2019).

Campos, L. C., Rocha, M. V. V., Willers, D. M. C. & Silva, D. R. Characteristics of patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in a region with high TB and HIV prevalence. PLoS ONE. 11(1), e147933 (2016).

Acuña-Villaorduña, C. et al. Host determinants of infectiousness in smear-positive patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Open Forum Infect. Dis https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz184 (2019).

Jones-López, E. C. et al. Importance of cough and M. tuberculosis strain type as risks for increased transmission within households. PLoS ONE. 9(7), e100984 (2014).

Kabilan, K. et al. Myriad faces of active tuberculosis: Intrapulmonary bronchial artery Pseudoaneurysm. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 56(2), 212–215 (2022).

Shaw, J. A., Diacon, A. H. & Koegelenberg, C. F. N. Tuberculous pleural effusion. Respirology 24(10), 962–971 (2019).

Unnewehr, M., Meyer-Oschatz, F., Friederichs, H., Windisch, W. & Schaaf, B. Clinical and imaging factors that can predict contagiousness of pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Pulm. Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-023-02617-y (2023).

Méchaï, F. & Bouchaud, O. Tuberculous meningitis: Challenges in diagnosis and management. Rev. Neurol.France. 175(7–8), 451–457 (2019).

Moule, M. G. & Cirillo, J. D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis dissemination plays a critical role in pathogenesis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00065 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank teachers and parents for their support, as well as all of the students who participated in the project.

Funding

The Sichuan Provincial Cadre Health Research Project, Grant No. 2021 − 230. The National Natural ScienceFoundation of China, No.82202147. Sichuan Science and Technology Program, Grant No.2022YFS0075. Liangshan Science and Technology Bureau, Grant No. 21ZDY0069.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(1) Conception and design:Lan Shang and Weifang Kong (2) Provision of study materials or patients: Yan Gao and Junzhu Lu, (3) Collection and assembly of data: Junzhu Lu and Shiqing Yu, (4) Data analysis and interpretation: Rongping Zhang, Guojin Zhang and Weifang Kong and Xinyue Chen, (5) Manuscript writing: Shiqing Yu and Yan Gao, (6) Final approval of manuscript: Lan Shang and Weifang Kong. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All clinical data and laboratory results, as well as the waiver of patient informed consent has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Sichuan Provincial Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Protocol 20220–254).

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Gao, Y., Lu, J. et al. Clinical profiles and related factors in tuberculosis patients with positive sputum smear mycobacterium tuberculosis tests. Sci Rep 14, 20376 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71403-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71403-5