Abstract

Current studies have mainly focused on the effect of specific steel fibers on the shear performance of steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) slender beams. However, there has been a lack of in-depth research evaluating the effectiveness of different steel fibers through a statistically comparative analysis of experimental data from various researchers. Existing design methods do not fully account for the impact of all types of steel fibers on the shear capacity of SFRC slender beams, providing very limited guidance on selecting appropriate steel fibers. This highlights the need for research to verify the strengthening effectiveness of different steel fibers. This paper establishes databases comprising 232 shear-failed reinforced SFRC beams with four other types of steel fibers straight wire, deformed wire, deformed cut-sheet and ingot mill, based on a comprehensive review of published literature. These databases complement an existing database of 280 reinforced SFRC beams using hook-end wire steel fibers as shear reinforcement. The databases are used to evaluate the validity of several well-known existing formulas for predicting the shear capacity of beams and to determine the fiber bond factor values that reflect the diverse strengthening effects of different steel fibers. Utilizing a simi-empirical synergetic prediction model for the shear strength of reinforced SFRC slender beams with hook-end wire steel fibers, the shear resistances of test beams in databases with the other four types of steel fiber are analyzed. The primary contributors to shear capacity are identified as the uncracked shear-compression SFRC and the dowel action of longitudinal tensile steel bars. The contribution of steel fibers is linked to the shear resistance of uncracked shear-compression SFRC. From a practical design perspective, a conservative prediction formula is verified, aligning with the lower boundary of the tested shear strength obtained from the database of beams. Finally, suitable steel fibers for s enhancing the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars are suggested based on their effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is widely applied in structural engineering due to its high strength under compression, good fire resistance with poor heat conduction, good formability to different geometries, easy fabrication with local raw materials, and lower construction costs. However, it has weaknesses, including heavy self-weight, lower tensile strength, and poor durability in severe environmental conditions1. Therefore, there has been an ongoing exploration of methods to enhance concrete performance, one of which involves incorporating shorter and thinner steel fibers to create high-performance concrete. Since 1963, Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) has been researched to improve early-age cracking resistance, tensile strength and flexural toughness, as well as to get related performances such as crack control, fatigue resistance, impact resistance, explosion proofing, and high durability2,3,4. The research is still ongoing in pursuit of better results for use in infrastructure engineering.

Distinguished from PE, PP, and PVA fibers, steel fibers possess the advantages of high elastic modulus and toughness5,6. This allows steel fibers to effectively ameliorate early-age cracking issues in concrete, enhancing its flexural strength, impact resistance, and residual strength7,8,9. Additionally, unlike steel rebars, steel fibers, even at lower volume fractions, exhibit no difference in conductivity compared to concrete and do not impact the concrete's durability4. In the process of development, different steel fibers have been produced from carbon steel using the methods such as wire-cut, thin-plate cut, thick plate or ingot mill, and molten steel wire-drawn5. Nowadays, the most commonly applied methods to produce steel fibers wire-cut, thin-plate cut, and ingot mill6,10,11. Steel fibers produced by the wire-cut method use cold-drawn steel bars with diameters ranging from 0.4 to 0.8 mm, possessing tensile strengths exceeding 1000 MPa. To overcome the deficiency of lower bond to the concrete matrix due to the smooth surface, these fibers are often manufactured with a hook-end or crimped shape12,13. Steel fibers produced by the cut sheet method use thin plates with a tensile strength of less than 1000 MPa. With different manufacturing techniques, these steel fibers can be made in various shapes, such as dumbbells, indented, and crimped6,11,13. Steel fibers produced by the ingot mill method use steel with tensile strength lower than 600 MPa and have a longitudinal distorted shape with a crescent section. These fibers, manufactured by special techniques, are half smooth and half rough longitudinally, with enlarged ends14,15.

With the research of SFRC, its application has expanded into various engineering fields, such as building structures, industrial building grounds, urban roads and bridges, tunnels, slope supporting, and repairing and strengthening projects16. Additionally, SFRC is used in pervious frames for river revetment17. A typical application of SFRC is enhancing the load-bearing performance of the structural members, including columns under eccentric or axial compression18,19, beams subjected to bending, shear, or torsion20,21,22, and beam-column joints in bending and shear23. In the context of SFRC slender beams subjected to bending, steel fibers can effectively improve serviceability by improving the cracking resistance, reducing crack width, and enhancing flexural stiffness, particularly post-cracking residual stiffness. However, they only provide a modest increase in bending strength24,25,26,27. Meanwhile, the shear strength of slender beams can be remarkably strengthened due to the corresponding contributions of steel fibers28,29,30,31. The presence of steel fibers effectively mitigates shear cracking in slender beams32,33, prompting ongoing research into the shear performance, especially the shear strength of reinforced SFRC slender beams34,35,36.

However, due to the complex mechanisms governing the shear strength of reinforced concrete beams, even in the absence of web rebars, a unified theoretical approach has not yet been established, resulting in a disparity in current worldwide codes37,38,39,40. The presence of steel fibers further complicates this by affecting almost all aspects that influence the shear strength, including the uncracked shear-compression SFRC, the dowel action between longitudinal rebars and SFRC, the aggregate interlock along sides of shear cracks, and the bridging effect of steel fibers across shear cracks41,42,43,44,45,46. This has led to an important research direction in the area of establishing empirical prediction formulas for the practical design of SFRC beams31,47,48,49,50,51. In this aspect, the reliability of empirical prediction formulas depends on the rational compositions of influencing factors and the comprehensiveness of experimental data. Therefore, the authors of this paper conducted a semi-empirical synergistic analysis specifically on longitudinally reinforced beams incorporating hook-end steel fiber produced by the wire-cut method36. A database was established for 280 reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars that failed in shear accompanied by 37 reinforced SFRC slender beams that failed in flexure and 71 reinforced conventional concrete beams that failed in shear. An effective prediction formula has been proposed, encompassing contributions from uncracked shear-compression SFRC, dowel action of longitudinal tensile steel bars, aggregate interlock between sides of the critical shear crack, and shear resistance of steel fibers bridging shear cracks as well as the size effect of sectional depth. This serves as a foundational framework for exploring the shear capacity of longitudinally reinforced SFRC slender beams employing other types of steel fibers.

Through an extensive review of relevant literature, in addition to the predominant use of hook-end steel fibers for enhancing the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars, studies have also been conducted on shear strengthening using wire-cut steel fibers in the shape of straight24,28,52,53,54, indented55 and crimped31,56,57,58,59, the deformed cut sheet steel fibers in the shape of dumbbell60, indented28,56,61,62 and crimped62,63,64,65, and the ingot mill steel fibers66,67. Generally, the inclusion of steel fibers, irrespective of their types, benefits to the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars. Steel fibers enhance post-cracking tension resistance, limit the propagation of diagonal cracks, thereby improving aggregate interlock between shear crack surfaces, and augment the dowel action of longitudinal tensile rebars28,31,36,47,48,49,50. Moreover, the presence of sufficient steel fibers notably enhances shear ductility in these beams, effectively transferring shear failure to flexural failure28,48,52,68, while the sectional size effect on shear strength could be mitigated or even eliminated69,70,71.

Research significance

Current studies have primarily focused on the effects of specific types of steel fibers on the shear performance of SFRC slender beams. However, there has been a lack of in-depth research evaluating the effectiveness of different steel fibers through a statistically comparative analysis of experimental datasets published by various researchers. While the effectiveness of steel fibers in enhancing the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams is acknowledged in design codes16,34, existing design methods fail to encompass all types of steel fibers, lacking a consensus-driven approach. This limitation hinders the practical application of different steel fibers, and cannot provide guidance of choosing reasonable steel fiber. Hence, it critically needs further research to recognize the contributions of various steel fibers towards enhancing the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams.

Therefore, this paper first establishes experimental databases by collecting and reanalyzing test data from literature studies that investigated the shear strength of longitudinally reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars. Given the intricate nature of the shear performance in reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars, databases of test beams are comprehensively established with different types of steel fiber. Corresponding to a database of 280 reinforced SFRC beams utilizing hook-end wire steel fibers as shear reinforcement36, this study includes databases comprising 232 shear-collapsed reinforced SFRC beams with various types of steel fibers, including straight wire, deformed wire, deformed cut-sheet or ingot mill. This provides a foundation for further research into the effectiveness of different steel fibers on the shear strength of longitudinally reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars, through comparison with results determined for hook-end steel fibers36. Initially, a comparative analysis assesses the applicability of widely recognized existing formulas used for predicting the shear capacity of the beams within the databases. Concurrently, considering the bond-slip mechanisms inherent to various steel fibers in the concrete matrix, values for the fiber bond factor are determined, which correspond to the strengthening impact of different steel fibers on the shear capacity of these beams. A systematic and integrated analysis then employing a multi-action shear model primarily proposed for reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars using hook-end steel fibers for shear reinforcement36, is conducted to evaluate how different steel fibers influence the various multi-action contributions to the shear capacity of these beams. Finally, conservative formulas are also examined to ensure dependable shear capacity in the design of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web reinforcement.

Databases of test beams

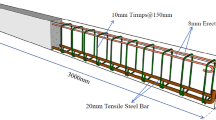

Based on the surface morphology, geometry and production method of steel fibers, they are divided into five types for shear reinforcement in reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars: hook-end, straight wire, deformed (crimped/indented) wire, deformed cut sheet and ingot mill6,10. The database of test beams using hook-end steel fiber was built in a previous study36, and is detailed in Appendix 1 of this paper. This study establishes the databases for test beams using the other four types of steel fibers, detailed in Appendices 2 and 3. Similarly, test beams are limited to slender beams, defined as having a span at least five times their sectional depth, primarily deforming in flexure39,42. The test data, drawn from published literature, adheres to specific dimensional criteria10,16,67. The beams' width and depth must be at least three times the maximum fiber length to ensure proper fiber dispersion and orientation within the concrete matrix, accounting for the 'wall effect' caused by the formwork during beam fabrication8,14,34. To standardize results and negate geometric size differences, the self-weight of the test beams is factored into the shear capacity calculations using an assumed unit weight of 24.5 kN/m3 for SFRC. Additionally, because the standard specimen size for SFRC compressive strength testing is Φ150 mm × 300 mm cylinders5,72,73, test results from the literature24,31,51,56,59,60,62,63,64,65,66 using 150 mm cubic specimens are adjusted with a reduction factor of 0.85.

Table 1 details the foundational attributes of the database encompassing 232 reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars that experienced shear failure. The distribution of steel fibers used in these beams is as follows: 61 beams utilized straight wire steel fiber, 65 beams employed deformed wire steel fiber (16 with indented wire 55, and 49 with crimped wire), 93 beams utilized deformed cut sheet steel fiber (6 with dumbbell60), and 13 beams utilized ingot mill steel fiber. The beams' sectional depth-to-width ratio (h/b) spanned from 1.0 to 3.93, with an exception of three one-way slabs having a ratio of 0.555. The longitudinal tensile steel bars' reinforcement ratio (ρ) varied between 1.16% and 5.72%. The shear-span-to-depth ratio (λ) fluctuated between 1.0 and 5.0. The volume fraction (vf) of steel fiber ranged from 0.22 to 2.5%, with corresponding aspect ratios (lf/df) varying from 25.8 to 191. Additionally, the cylinder compressive strength (fcˊ) of SFRC ranged from 20.3 to 93.3 MPa. Meanwhile, the table also includes parameters such as the diameter of longitudinal tensile steel bars (ds) and the length of steel fibers (lf).

In order to facilitate direct referencing in future studies, the details of test data in the databases are included in the appendices of this paper. The database used for a semi-empirical synergistic analysis of longitudinally reinforced beams, specifically incorporating hook-end steel fiber24,30,47,49,58,60,68,69,70,71,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111, is also provided in an Appendix of this paper, which was not published previously 36.

Comparison to existing shear strength formulas

After studying various well-known existing formulas and verifying them using test results from reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars but employing cold-drawn wire hook-end steel fiber36, it was observed that several formulas provided comparatively higher accuracy in predicting the shear capacity of reinforced SFRC beams without stirrups. Notably, Narayanan & Darwish31, Ashour et al.47, Kwak et al.49, Li et al.50, and Arslan et al.51 proposed formulas that demonstrated enhanced predictive accuracy in this context.

Therefore, these five models of existing formulas, as presented in Table 2, are used for the comparison of test results in databases. To facilitate expression consistency across different literature sources, the symbols and terms representing the same parameters have been standardized. In Table 2, the symbols correspond to specific parameters: Vuc represents the shear capacity of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars, fcˊ denotes the compressive strength of SFRC tested by using a standard cylinder of ϕ150 mm × 300 mm, fspt stands for the splitting tensile strength of SFRC, fft stands for the tensile strength of SFRC, b and d signify the sectional width and effective depth of beam, ρ denotes the reinforcement ratio of longitudinal tensile steel bars, λ represents the shear-span (a) to depth (d) ratio, c denotes the depth of the shear-compression zone above the tip of diagonal crack on shear-span of beam, F signifies the fiber factor and vb stands for the tensile strength of steel fiber bridging shear crack.

The fiber factor F is expressed as,

The tensile strength vb of steel fiber bridging shear crack is expressed as,

Unlike the use of a constant τf = 0.415 MPa31,47,49, the fiber-concrete adhesion strength τf is calculated in this study as follows based on the bond property of steel fiber in the concrete matrix12,

Due to the lack of experimental data on the tensile strength of SFRC determined along with the test beams at the same condition, the splitting tensile strength fspt of SFRC is transferred from the formula proposed in previous studies31,49, that is,

Meanwhile, based on the composite mechanism of steel fibers with concrete matrix and the relationship between tensile strength and compressive strength of conventional concrete6,7, the tensile strength fft of SFRC can be calculated as follows,

Comparison results and discussion

Overviewing the formulas listed above, the fiber bond factor ηf in formula (8) is a key parameter that reflects the bond characteristic of steel fiber to the concrete matrix, which is dependent on the interface behavior between fiber and concrete matrix12,13. With the same concrete matrix, the surface roughness of steel fiber controls the chemical adhesion and physical friction at the initial bond-slip performance, and the deformed geometry of steel fiber provides the mechanical anchorage to resist the slip of fiber opposite to the concrete matrix. Therefore, the fiber with a rough surface is better than that with a smooth surface, and the deformed steel fiber has superior bond performance than the straight steel fiber. Narayanan and Darwish31 proposed ηf = 0.5 for round fibers, 0.75 for crimped fibers and 1.0 for indented fibers. Imam et al.48 proposed ηf = 0.5 for smooth fibers, 0.9 for deformed fibers and 1.0 for hook-end fibers. According to the tensile strength of SFRC specifications outlined in China codes JG/T472 and JGJ/T46510,16, the fiber bond factor can be converted as follows: ηf = 1.0 for hook-end fibers, 0.55 for straight fibers, 0.75 for deformed fibers and 0.9 for ingot mill fibers.

In this study, a base value of ηf = 1.0 is set for cold-drawn wire hook-end steel fiber, drawing from its excellent bond behavior. Subsequently, the values of ηf for other steel fibers are determined according to the statistical analyses of the shear capacity of examined beams in the database to facilitate accurate prediction, utilizing the same formula outlined in Table 2. The established values are as follows: ηf = 0.55 for straight wire steel fibers, ηf = 0.75 for deformed (crimped/indented) wire steel fibers, ηf = 0.90 for deformed cut sheet steel fibers, and ηf = 1.0 for ingot mill steel fibers.

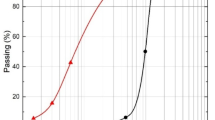

The statistical results of the test versus predicted shear strength ratios for the beams in the database are summarized in Table 3 and presented in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

As exhibited in Fig. 1, the formulas (2) and (3) proposed by Ashour et al.47 and the formulas (6) and (7) proposed by Arslan et al.51 tend to provide relatively lower prediction with an average ratio over 1.0. The latter exhibits more significant variability in predictions, particularly for beams employing straight wire, deformed cut sheet, and ingot mill steel fibers. It notably shows a tendency to underestimate the shear capacity, especially for beams with lower shear-span-to-depth ratios, particularly at λ ≤ 1.5.

As exhibited in Fig. 2, the formula (5) proposed by Li et al.50 conversely offers higher prediction, notably overestimating the shear capacity of beams with lower shear-span to depth ratios, especially at λ ≤ 1.5. Simultaneously, the formula (4) proposed by Kwak et al.49 tends to produce higher predictions for beams, except for those using straight wire steel fibers. Consequently, the formula (1) proposed by Narayanan and Darwish31 yields comparatively better prediction for the beams, exhibiting test versus predicted shear strength ratios close to 1.0 on average with smaller variations.

The comparative analysis overall highlights increased variability in predicting the shear strength of beams utilizing straight wire or deformed cut sheet steel fibers. This variability primarily hinges on the bonding characteristics specific to these types of steel fibers. The bonding strength of straight wire steel fibers heavily relies on fiber surface roughness to attain bond strength in concrete. The containment of straight wire steel fiber within the shear crack predominantly relies on the fiber length to establish adequate bond strength before potential pullout from the concrete28,54. Given its lower fiber bond factor, the use of straight wire steel fiber as shear reinforcement for reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars may not yield significant benefits. On the other hand, for deformed cut sheet steel fiber, the bonding characteristic involves various factors, including the deformed geometry and sectional size. The containment of fibers within the shear crack also relies on fiber length, as shorter fibers might pull out from the concrete due to insufficient bond strength63,65. Moreover, the cut-sheet production method is difficult to be standard, and the waste steel belts are always used for the mother sheet. This emphasizes the need to address the reliable bonding of deformed cut sheet steel fibers when determining production techniques.

Analysis of the steel fiber contribution to shear strength

Based on a simplified critical shear crack model, the shear capacity of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars contains four parts contributed by the uncracked shear-compression SFRC (Vc), the dowel action of longitudinal tensile steel bars (Vd), the aggregate interlock between sides of critical shear crack (Va), and the steel fibers across the critical shear crack (Vf). The formulas for predicting the shear strength of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars are introduced as follows36,

Figure 3 illustrates the comparison of the shear capacity of test beams in the databases to the predicted results using formula (13). It also includes the results for beams with hook-end steel fibers published in36 for convenience of comparison. The statistical results of the shear strength ratios for test beams with different types of steel fibers are summarized in Table 4. Notably, apart from test beams with straight wire steel fibers, formula (13) demonstrates accurate predictions for beams with hook-end wire, crimped/indented wire, deformed cut sheet or ingot mill steel fibers. This once again highlights the greater variability of straight wire steel fibers in enhancing the shear strength of beams, due to the larger variation of bond caused by their uncontrollable surface conditions 24,52,53,54. Meanwhile, due to a lack of standardization for the geometrical and deformed sizes of cut sheet steel fibers63,64,65, there is a significant difference in the morphology features, including surface and deformed shape, leading to a noticeable variation in the shear strength of test beams.

Comparisons of the shear capacity of test beams in databases to the predicted results using formula (13).

Contribution of steel fibers to each constituent of the shear strength

Utilizing the semi-empirical prediction formulas (13) in conjunction with the databases, the proportional contribution of each constituent to the shear capacity is estimated. The outcomes, depicted in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7, exhibit variations linked to the shear-span to depth ratio (λ) and the reinforcement ratio (ρ).

From Fig. 4, it's evident that the contribution of uncracked shear-compression SFRC diminishes from 61 to 18% with λ increasing from 1.5 to 5.0, displaying minimal influence from changes in ρ. This aligns with the shift in shear failure, transitioning from shear-compression to diagonal tension even to flexure, predominantly dictated by the ratio of moment to shear force47,55,74,85,89. Consequently, the depth of the shear-compression zone decreases, leading to a reduction in its shear resistance47,59,93. The presence of SFRC in the tension zone can enhance the bending capacity of the shear section, which benefits the shear resistance provided by uncracked shear-compression SFRC112,113. It is noticed that the variation of shear resistance provided by uncracked shear-compression SFRC with shear-span to depth ratio is consistent for the beams with different types of steel fibers. Meanwhile, the primary role of longitudinal tensile steel bars is to provide tensile force counteracting the compressive stress of uncracked shear-compression SFRC, demonstrating minimal impact on the beam's shear-induced failures. This leads to an unclear relationship between the Vc and ρ.

From Fig. 5, the contribution of the dowel action to the shear resistance escalates from 25 to 55% as λ rises from 1.0 to 3.0 and ρ increases from 0.75 to 3.0%. This underscores the pivotal role of the dowel action when the shear failure mode transitions from shear compression to diagonal tension114,115. Because the shear resistance of longitudinal tensile rebars is significantly enhanced with the high-tensile strength SFRC, the initiation and propagation of bonding cracks along the longitudinal tensile steel bars is delayed or prevented, mitigating splitting cracks along the bars, especially in diagonal tension conditions28,55,86,97,102. However, in scenarios dominated by diagonal tension as λ climbs from 3.0 to 5.0, the dowel action exhibits a slight increase since bonding failure along the steel bars is largely dependent on the prevention of the splitting of SFRC58,73,84. With rising ρ, the shear capability of longitudinal tensile rebars increases to counter transverse deformation at the section intersecting the critical shear crack and eliminate bond slip between SFRC and the bars. This creates an increase of shear resistance provided by the dowel action. Exceeding ρ beyond 3.0%, any further increase only marginally boosts the dowel action, owing to excessive reinforcement used in the beam tests intended to induce shear rather than flexural failure, particularly under conditions that the beams with λ ≥ 3.528,31,54,58.

From Fig. 6, the contribution of aggregate interlock increases from 10 to 25% as λ ascends from 1.0 to 5.0. This results from heightened sliding between the sides of shear cracks during diagonal tension failure. Conversely, there's a decrease observed with rising ρ. This decrease corresponds to greater confinement exerted by longitudinal tensile steel bars on the widening of shear cracks, while often amalgamating multiple critical shear cracks at the point of failure109,115.

From Fig. 7, the contribution of steel fibers bridging shear cracks typically remains below 5%. Aside from the quantity of steel fibers, this contribution is directly linked to the specific type of steel fiber. It's evident that straight wire steel fiber performs the least effectively. This reaffirms that not every type of steel fiber is suitable for serving as shear reinforcement in reinforced SFRC slender beams lacking web rebars.

In general, the contribution of each continent of the shear capacity expresses a similar variation linked to the shear-span to depth ratio and the reinforcement ratio, whatever the types of steel fibers. This indicates that the steel fibers strengthen the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars in the same mechanism. Therefore, the difference in the strengthening effectiveness of steel fibers on the shear strength of beams comes from the bonding characteristics of steel fibers in the concrete matrix. Therefore, the primary contributors to shear capacity are identified as the uncracked shear-compression SFRC and the dowel action of longitudinal tensile steel bars, the contribution of steel fibers related to the shear resistance of uncracked shear-compression SFRC.

Shear strength prediction using simplified semi-empirical formula

The above comprehensive analysis notably identifies that the uncracked shear-compression SFRC and the dowel action of longitudinal tensile steel bars are pivotal factors dictating the shear capacity of the beams. This means that formula (13) can be streamlined to form a conservative estimate for the shear capacity of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars, as follows,

With a similar treatment to obtain sufficient reliability of designed shear strength for reinforced SFRC or conventional concrete beams in specifications of Chinese code JGJ/T 45616 and GB 50,01032, for the convenience of the application in design process, the formula (20) can be further simplified as36,

where λ = 1.2 for λ < 1.2, and λ = 4.5 for λ > 4.5.

Let \(\beta_{\rho } = 1 + 5\sqrt \rho\) and \(\beta _{{\text{f}}} = 0.22f_{c}^{{\prime \,0.55}} \left( {{\text{1 + 1}}{\text{.05}}F} \right)\), the comparison of test versus predicted results are presented in Fig. 8. The statistical results shear capacity ratios for test beams with different types of steel fibers are summarized in Table 5. As discussed in the previous study of beams with hook-end steel fibers, formula (21) predicts the shear strength of test beams at a lower boundary, and the strengthening effectiveness of steel fiber is identified using the different fiber factor F36. However, it should be noted that larger variations are presented in the predicted shear strength using formula (21) for the beams with straight wire and deformed cut sheet steel fibers.

Comparisons of the shear capacity of test beams in databases to the predicted results using formula (21).

Conclusions

To evaluate the strengthening effectiveness of different steel fibers on the shear strength of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars, statistical analyses were conducted using established databases comprising 280 reinforced SFRC beams utilizing hook-end wire steel fibers as shear reinforcement from previous studies, and 232 beams from this study: 61 with straight wire steel fibers, 65 with indented/crimped wire steel fibers, 93 with deformed cut sheet steel fiber, and 13 with ingot mill steel fiber.

Test results of the beams in the databases are comprehensively discussed through the comparison to predicted shear capacities using well-known existing formulas. With a premise of higher prediction accuracy and considering the bond characteristics of steel fibers in the concrete matrix, fiber bond factor values were determined to represent the strengthening effects of steel fibers on both the tensile strength of SFRC and the shear capacity of the beams. As a result, a fiber bond factor value of 1.0 is obtained for cold-drawn wire hook-end and ingot mill steel fibers, 0.90 for deformed cut sheet steel fibers, 0.75 for deformed (crimped/indented) wire steel fibers, and 0.55 for straight wire steel fibers. This order reflects the strengthening effectiveness of different steel fibers on the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars.

A semi-empirical synergetic prediction model that considers multiple actions was employed to evaluate the contributions of steel fibers to the constituents of shear capacity, including the uncracked shear-compression SFRC, dowel action, aggregate interlock, and steel fibers bridging the shear crack. It is observed that the uncracked shear-compression SFRC and dowel action collectively constitute over 80% of the total shear strength. The aggregate interlock and steel fibers bridging the shear crack contribute to the shear strength of the beam to a certain extent. Since the shear strength contributed by the uncracked shear-compression SFRC directly depends on the tensile strength of SFRC, the effect of steel fiber on shear strength is reflected in this constituent of the shear strength of the beams.

The adaptability of a conservative prediction formula proposed in a previous study was verified to facilitate its practical application in design. This formula accounts for the variations in shear-span to depth ratio, longitudinal tensile reinforcement ratio, and the strengthening effect of steel fiber, providing valuable insights for the rational design of beams, aiding in the arrangement of longitudinal tensile rebars and the selection of suitable steel fibers for shear reinforcement.

It is worth noting that while different steel fibers strengthen the shear strength of reinforced SFRC beams without web rebars, their effectiveness varies. Hook-end and ingot mill steel fibers offer the highest strengthening effectiveness, followed by cut-sheet steel fibers and deformed wire steel fibers, with the straight wire steel fibers being the least effective. However, using cut-sheet steel fibers leads to a considerable variation in the shear strength of the beams.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- b :

-

Width of normal-cross section for beam

- h :

-

Depth of normal-cross section for beam

- d :

-

Effective depth of normal-cross section for beam

- c :

-

Depth of the shear-compression zone above the tip of diagonal crack on shear-span of beam

- d s :

-

Diameter of longitudinal tensile steel bar

- a :

-

Shear-span from the load-plate center to the support center

- λ :

-

Shear-span to depth ratio, λ = a/d

- ρ :

-

Reinforcement ratio of longitudinal tensile rebars for a beam

- l f :

-

Fiber length

- d f :

-

Fiber diameter

- l f/d f :

-

Aspect ratio of steel fiber

- v f :

-

Volume fraction of steel fiber

- η f :

-

Fiber bond factor

- τ f :

-

Fiber-concrete adhesion strength

- F :

-

Fiber factor

- f cu :

-

Cubic compressive strength of SFRC tested using standard cube with a dimension of 150 mm

- f cˊ:

-

Compressive strength of SFRC tested using standard cylinder of ϕ150 mm × 300 mm

- f spt :

-

Splitting tensile strength of SFRC

- f ft :

-

Tensile strength of SFRC

- v b :

-

Tensile strength of steel fibers across critical shear crack

- V uc :

-

Shear capacity of beam without web rebars

- V uc,t :

-

Tested shear capacity of beam without web rebars

- V c :

-

Shear resistance provided by the shear-compression SFRC of a beam without web rebars

- V d :

-

Shear resistance of the dowel action of a beam without web rebars

- V a :

-

Shear resistance of the aggregate interlock of a beam without web rebars

- V f :

-

Shear resistance of steel fiber bridging critical shear cracks of a beam without web rebars

- θ :

-

Average slant angle of the critical shear crack to longitudinal axis of a beam without web rebars

- ϕ d :

-

Size effect factor considering the sectional depth of a beam without web rebars

References

Zhao, G. & Zhou, D. Advanced Reinforced Concrete Structures (China Machine Press, 2005).

Edgington, J. & Hannant, D. J. Steel fiber reinforced concrete. The effect on fiber orientation of compaction by vibration. Matér. Constr. 5(1), 41–44 (1972).

Swamy, R. N. & Mangat, P. S. Influence of fiber-aggregate interaction on some properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Matér. Constr. 7(5), 307–314 (1974).

Zhao, G., Peng, S. & Huang, C. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Structure (China Building Industry Press, 1999).

CECS13:2009. Standard Test Methods for Fiber Reinforced Concrete (China Plan Press, 2009).

ASTM A820–01, Standard Specification for Steel Fiber for Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (ASTM Committee A01, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, USA, 2001).

Zhao, M., Li, J. & Law, D. Effects of flowability on SFRC fiber distribution and properties. Magaz. Concr. Res. 69(20), 1043–1054 (2017).

Ding, X., Li, C., Han, B., Lu, Y. & Zhao, S. Effects of different deformed steel-fibers on preparation and properties of self-compacting SFRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 168, 471–481 (2018).

Ding, X. et al. Prediction of the complete flexural load-deflection curve of self-compacting concrete reinforced with hook-end steel fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134003 (2023).

JG/T472. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (China Standard Press, 2015).

Zhao, M. Study on Shear Behaviours of Reinforced High-Performance SFRC Beams (RMIT University, 2023).

Ding, X., Zhao, M., Li, C., Li, J. & Zhao, X. A multi-index synthetical evaluation of bond behaviors of hooked-end steel fiber embedded in mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 276, 122219 (2021).

Ding, X., Geng, H., Zhao, M., Chen, Z. & Li, J. Synergistic bond behaviors of different deformed steel fibers embedded in mortars wet-sieved from self-compacting SFRC with manufactured sand by using pull-out test. Appl. Sci. 11(21), 10144 (2021).

Zhao, M., Li, J. & Xie, Y. M. Effect of vibration time on steel fiber distribution and flexural properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete with different flowability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01114 (2022).

Zhao, M., Li, J., Xie, Y. M., Shen, J. & Li, C. Experimental study of the bond behavior of 400MPa hot-rolled ribbed steel bars to high-flowability steel fiber reinforced concrete. Sci. Rep. 14, 4066 (2024).

JGJ/T465-2019. Design Code for Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Structures (China Building Industry Press, 2019).

Geng, H. et al. Application of self-compacting steel fiber reinforced concrete for pervious frames used for river revetment. Appl. Sci. 15(20), 10457 (2022).

Li, C., Geng, H., Deng, C., Li, B. & Zhao, S. Experimental investigation on columns of steel fiber reinforced concrete with recycled aggregates under large eccentric compression load. Materials 12(3), 445 (2019).

Liu, S., Ding, X., Li, X., Liu, Y. & Zhao, S. Behavior of rectangular-sectional steel tubular columns filled with high-strength steel fiber-reinforced concrete in axial compression. Materials 12(17), 2716 (2019).

Mpalaskas, A. C., Matikas, T. E., Aggelis, D. G. & Alver, N. Acoustic emission for evaluating the reinforcement effectiveness in steel fiber reinforced concrete. Appl. Sci. 11, 3850 (2021).

Kachouh, N., El-Maaddawy, T., El-Hassan, H. & El-Ariss, B. Shear response of recycled aggregates concrete deep beams containing steel fibers and web openings. Sustainability 14, 945 (2022).

Deifalla, A. F., Zapris, A. G. & Chalioris, C. E. Multivariable regression strength model for steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams under torsion. Materials 14, 3889 (2021).

Gao, D., Shi, K. & Zhao, S. Calculation method for bearing capacity of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete beam-column joints. J. Build. Struct. 35(2), 71–79 (2014).

Noghabai, K. Beams of fibrous concrete in shear and bending: experiment and model. J. Struct. Eng. 126(2), 243–251 (2000).

Li, C., Li, Q., Li, X., Zhang, X. & Zhao, S. Elasto-plastic bending behaviors of reinforced SFRELC beams analyzed by nonlinear finite-element method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 13, e00372 (2020).

Li, X., Pei, S., Fan, K., Geng, H. & Li, F. Bending performance of SFRC beams based on composite-recycled aggregate and matched with 500MPa rebars. Materials 13(4), 930 (2020).

Kytinou, V. K., Chalioris, C. E. & Karayannis, C. G. Analysis of residual flexural stiffness of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams with steel reinforcement. Materials 13, 2698 (2020).

Batson, G., Jenkins, E. & Spatney, R. Steel fibers as shear reinforcement in beams. ACI J. Proc. 69(10), 640–644 (1972).

Swamy, R. N. & Bahia, H. M. Influence of fiber reinforcement on the dowel resistance to shear. ACI J. 76(2), 327–356 (1979).

Sharma, A. K. Shear strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 83(4), 624–628 (1986).

Narayanan, R. & Darwish, Y. S. Use of steel fibers as shear reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 84(3), 216–227 (1987).

Li, C. et al. Effect of steel fiber content on shear performance of reinforced expanded-shale lightweight concrete beams with stirrups. Materials 14(5), 1107 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Shear performance of steel fiber reinforced expanded-shale lightweight concrete beams with varying of shear-span to depth ratio and stirrups. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 14, e00550 (2021).

ACI 544.4R-2009, Design Considerations for Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (ACI Committee 544, ACI: Farmington Hill, MI, USA, 2009).

Lantsoght, E. O. L. How do steel fibers improve the shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams without stirrups?. Compos. Part B 175, 107079 (2019).

Zhao, M., Li, J., Xie, Y. M. & Shen, J. Semi-empirical synergetic analysis of the shear capacity of steel fiber reinforced concrete slender beams of rectangular-sections without stirrups. Eng. Struct. 285, 116035 (2023).

Eurocode 2. Design of Concrete Structures: Part 1–1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings (British Standards Institution, London, 2004).

International Federation for Structural Concrete (fib), fib model Code for Concrete Structures 2010 (Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Rotherstraße 21, 10245 Berlin, Germany, 2013).

GB 50010–2010, Code for Design of Concrete Structures (China Building Industry Press, 2010).

ACI 318–19. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete; ACI Committee 318, ACI: Farmington Hill, MI, USA, 2019.

Vecchio, F. J. & Collins, M. P. The modified compression-field theory for reinforced-concrete elements subjected to shear. ACI J. 83(2), 219–231 (1986).

Dinh, H. H., Montesinos, G. J. P. & Wight, J. K. Shear strength model for steel fiber reinforced concrete beams without stirrup reinforcement. J. Struct. Eng. 137(10), 1039–1051 (2011).

Kim, K. S., Lee, D. H., Hwang, J. & Kuchma, D. A. Shear behavior model for steel fiber-reinforced concrete members without transverse reinforcements. Compos. Part B 43, 2324–2334 (2012).

Barros, J. A. O. & Foster, S. J. An integrated approach for predicting the shear capacity of fiber reinforced concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 174, 346–357 (2018).

Bernat, A. M., Spinella, N., Recupero, A. & Cladera, A. Mechanical model for the shear strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) beams without stirrups. Mater. Struct. 53, 28 (2020).

Tung, N. D. & Tue, N. V. Shear resistance of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams without conventional shear reinforcement on the basis of the critical shear band concept. Eng. Struct. 168, 698–707 (2018).

Ashour, S. A., Hasanain, G. S. & Wafa, F. F. Shear behavior of high-strength fiber reinforced concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 89(2), 176–184 (1992).

Imam, M., Vandewalle, L., Mortelmans, F. & Gemert, D. V. Shear domain of fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 19(9), 738–747 (1997).

Kwak, Y. K., Eberhard, M. O. & Kim, W. S. Shear strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. ACI Struct. J. 99(4), 530–538 (2002).

Li, F., Zhao, S. & Huang, C. Design method of shear resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. Ind. Constr. 33(10), 66–68 (2003).

Arslan, G. Shear strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) slender beams. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 18(2), 587–594 (2014).

Cheriyan, A., Krishnan, S. Contribution of fibers in SFRC beams failing in shear, in: Fiber Reinforced Cement and Concrete, Proc. RILEM Symposium, Sheffield: Rilem Technical Committee 49-TFR. 541–553 (1992).

Lim, D. H. & Oh, B. H. Experimental and theoretical investigation on the shear of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 21, 937–944 (1999).

Zhang, W., Cheng, T., Wang, W. Study on shear property of reinforced SFRC beams, Proc. of Third Conference on Basic Principle and Application of Concrete Structures, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 461–468 (1990).

Uomoto, T., Weeraratne, R.K.W., Furukoshi, H., Fujino, H. Shear strength on reinforced concrete beams with fiber reinforcement. Proc. Third International Symposium on Developments in Fiber Reinforced Cement and Concrete. RILEM Symposium, 2, 13–17 (1986).

Swamy, R. N. & Bahia, H. M. The effectiveness of steel fibers as shear reinforcement. Concr. Int. 7(3), 35–40 (1985).

Furlan, S. & de Hanai, J. B. Shear behaviour of fiber reinforced concrete beams. Cem. Concr. Compos. 19(4), 359–366 (1997).

Singh, B. & Jain, K. An appraisal of steel fibers as minimum shear reinforcement in concrete beams (with Appendix). ACI Struct. J. 111(5), 1191–1202 (2014).

Kannam, P., Sarella, V. R. & Kumar, P. R. A study on the influence of a/d ratio and stirrup spacing on shear behaviour of steel fiber reinforced SCC. Cem. Wapno Beton 13(6), 405–422 (2016).

Greenough, T. & Nehdi, M. Shear behavior of fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete slender beams. ACI Mater. J. 105(5), 468–477 (2008).

Zhang, H. Experimental Study on Shear Resistance Properties of Steel Fiber Reinforced High-strength Concrete Members. Doctoral Dissertation, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, (2005).

Nzambi, A. K. L. L., Oliveira, D. R. C., Monteiro, M. V. S. & Silva, L. F. A. Experimental analysis of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams in shear. IBRACON Struct. Mater. J. 15(3), e15301 (2022).

Gao, D., Zhao, J., Zhu, H. & Zhang, Q. The experimental research on the shear behavior of partial steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. J. Hydraulic Eng. 2, 28–32 (1999).

Zhao, S. Study on the Design Method of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete and Prestressed Concrete Structural Members. Doctoral Dissertation, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, (1996).

Li, F. Study on Calculation Method of Reinforced SFRC beams under shear. Master Dissertation, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, (2002).

Jiang, P. Experimental Study on Shear Behaviors of Steel Fiber Reinforced High-strength Concrete Beams. Master Dissertation, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2005.

Zhao, J., Liang, J., Chu, L. & Shen, F. Experimental study on shear behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams with high-strength reinforcement. Materials 11(9), 1682 (2018).

Minelli, F. & Plizzari, G. A. On the effectiveness of steel fibers as shear reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 110(3), 379–390 (2013).

Minelli, F., Conforti, A., Cuenca, E. & Plizzari, G. Are steel fibers able to mitigate or eliminate size effect in shear. Mater. Struct. 47, 459–473 (2014).

Zarrinpour, M. R. & Chao, S. Shear strength enhancement mechanisms of steel fiber-reinforced concrete slender beams. ACI Struct. J. 114(3), 729–742 (2017).

Dinh, H. H., Montesinos, G. J. P. & Wight, J. K. Shear behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams without stirrup reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 107(5), 597–606 (2010).

ASTM C1609/C1609M-12. Standard Test Method for Flexural Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (Using Beam with Third-point Loading) (ASTM Committee C09, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, USA, 2012).

GB50081-2019. Standard for Test Method of Mechanical properties on Concrete (China Building Industry Press, 2019).

Mansur, M. A., Ong, K. C. G. & Paramasivam, P. Shear strength of fibrous concrete beams without stirrups. J. Struct. Eng. 112(9), 2066–2079 (1986).

Folino, P., Ripani, M., Xargay, H. & Rocca, N. Comprehensive analysis of fiber reinforced concrete beams with conventional reinforcement. Eng. Struct. 202, 109862 (2020).

Tan, K. H., Murugappan, K. & Paramasivam, P. Shear behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 89(6), 3–11 (1992).

Shoaib, A., Lubell, A.S., Bindiganavile, V.S. Shear in Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Members without Stirrups. Structural Engineering Report No. 294, University of Alberta, Canada. 2012.

Yoo, D. & Yang, J. Effects of stirrup, steel fiber, and beam size on shear behavior of high-strength concrete beams. Cem. Concr. Compos. 87, 137–148 (2018).

Li, V. C., Ward, R. & Hmaza, A. M. Steel and synthetic dibers as shear deinforcement. ACI Mater. J. 89(5), 499–508 (1992).

Casanova, P., Rossi, P. & Schaller, I. Can steel fibers replace transverse reinforcements in reinforced concrete beams?. ACI Mater. J. 94(5), 341–354 (1997).

Adebar, P., Mindess, S., Pierre, D. S. & Olund, B. Shear tests of fiber concrete beams without stirrups. ACI Struct. J. 94(1), 68–76 (1997).

Rosenbusch, J., Teutsch, M. Brite/Euram Project 97-4163 Final Report Sub Task 4.2; Technical University of Braunschweig: Braunschweig, Germany, 105–117 (2003).

Amin, A. & Foster, S. J. Shear strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams with stirrups. Eng. Struct. 111, 323–332 (2016).

Navarro-Gregori, J., Navas, F.O., Herdocia, G.L., Serna, P., Cuenca, E. Experimental reexamination of classic shear-critical concrete beams tests including fibers. Proc.: 9th RILEM International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Concrete, Vancouver, Canada (2016).

Lim, T. Y., Paramasivam, P. & Lee, S. L. Shear and moment capacity of reinforced steel-fiber-concrete beams. Magaz. Concr. Res. 39(140), 148–160 (1987).

Ding, Y., You, Z. & Jalali, S. The composite effect of steel fibers and stirrups on the shear behaviour of beams using self-consolidating concrete. Eng. Struct. 33, 107–117 (2011).

Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, S. & Liu, H. Study on shear resistance of steel fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete beams. J. Hydraul. Eng. 42(4), 461–468 (2011).

Zhang, F., Shi, Y., Ni, K., Zhang, Y., Liu, W. Influence of steel fibers and stirrups on the shear behavior of self-consolidating concrete beams, Proc. The Eleven Symposium on High-performance Concrete, Harbin, China (2015).

Arslan, G., Keskin, R. S. O. & Ulusoy, S. An experimental study on the shear strength of SFRC beams without stirrups. J. Theore. Appl. Mechan. 55(4), 1205–1217 (2017).

Gali, S. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. Efficiency of steel fibers in shear resistance of reinforced concrete beams without stirrups at different moment-to-shear ratios. Eng. Struct. 188, 249–260 (2019).

Zhang, J., Zhang, D., Feng, C. & Cao, W. Experimental research on shear performance of HRB steel and high-strength concrete beams without web reinforcement. Eng Mech. 37, 275–281 (2020).

Dancygier, A. N. & Savir, Z. Effects of steel fibers on shear behavior of high-strength reinforced concrete beams. Adv. Struct. Eng. 14(5), 745–761 (2011).

Imam, M., Vandewalle, L. & Mortelmans, F. Shear-moment analysis of reinforced high strength concrete beams containing steel fibers. Cana. J. Civ. Eng. 22, 462–470 (1995).

Jiang, L. The experimental study of steel fiber as shear reinforcement. J. Guangxi Inst. Technol. 5(4), 20–26 (1994).

Dupont, D. & Vandewalle, L. Shear capacity of concrete beams containing longitudinal reinforcement and steel fibers. In Innovations in Fiber Reinforced Concrete for Value, SP-216 (eds Banthia, N. et al.) 79–94 (American Concrete Institute, 2003).

Cucchiara, C., Mendola, L. & Papia, M. Effectiveness of stirrups and steel fibers as shear reinforcement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 26, 777–786 (2004).

Kargh-Poulsen, J., Hoang, L. C. & Goltermann, P. Shear capacity of steel and polymer fiber reinforced concrete beams. Mater. Struct. 44, 1079–1091 (2011).

Aoude, H., Belghiti, M., Cook, W. D. & Mitchell, D. Response of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams with and without stirrups. ACI Struct. J. 109(3), 359–367 (2012).

Kang, T.-K., Kim, W., Massone, L. M. & Galleguillos, T. A. Shear-flexure coupling behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 109(4), 435–444 (2012).

Spinella, N., Colajanni, P. & Mendola, L. L. Nonlinear analysis of beams reinforced in shear with stirrups and steel fibers. ACI Struct. J. 109(1), 53–64 (2012).

Chalioris, C. E. & Sfiri, E. F. Shear performance of steel fibrous concrete beams. Proc. Eng. 14, 2064–2068 (2011).

Hwang, J.-H., Lee, D. H., Kim, K. S., Ju, H. & Seo, S.-Y. Evaluation of shear performance of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams using a modified smeared-truss model. Magaz. Concr. Res. 65, 283–296 (2013).

de Araújo, D. L., Nunes, F. G. T., Filho, T. R. D. & de Andrade, M. A. S. Shear strength of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Acta Scientiarum Technol. 36(3), 389–397 (2014).

Sahoo, D. R. & Sharma, A. Effect of steel fiber content on behavior of concrete beams with and without stirrups. ACI Struct. J. 111(5), 1157–1166 (2014).

Aoude, H. & Cohen, M. Shear response of SFRC beams constructed with SCC and steel fibers. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 14, 71–83 (2014).

Sahoo, D. R., Bhagat, S. & Reddy, T. C. V. Experimental study on shear-span to effective-depth ratio of steel fiber reinforced concrete T-beams. Mater. Struct. 49, 3815–3830 (2016).

Kim, C., Lee, H., Park, H.-G., Hong, G.-H. & Kang, S. Effect of steel fibers on minimum shear reinforcement of high-strength concrete beams. ACI Struct. J. 114(5), 1109–1119 (2017).

Anand, R. M., Sathya, S. & Sylviya, B. Shear strength of high-strength steel fiber reinforced concrete rectangular beams In. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 8(1716), 1729 (2017).

Yuan, T., Yoo, D., Yang, J. & Yoon, Y. Shear capacity contribution of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete compared with and without stirrup. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 14, 21 (2020).

Hemstapat, N., Okubo, K. & Niwa, J. Prediction of shear capacity of slender reinforced concrete beams with steel fiber. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 18, 179–191 (2020).

Lantsoght, E. O. L. Database of shear experiments on steel fiber reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. Materials 12(6), 917 (2019).

Guo, Y., Liu, J. & Li, Z. Study on compression-shear failure of steel fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Mater. 11(2), 152–156 (2008).

Gao, D., Zhu, H. & Tang, J. Shear strength of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete. J. Chin. Ceram. Soci. 33(1), 82–86 (2005).

de Resende, T. L., Cardoso, D. C. T. & Shehata, L. C. D. Influence of steel fibers on the dowel action of RC beams without stirrups. Eng. Struct. 221, 111044 (2020).

Ruiz, M. F., Muttoni, A. & Sagaseta, J. Shear strength of concrete members without transverse reinforcement: A mechanical approach to consistently account for size and strain effects. Eng. Struct. 99, 360–372 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Introduced International Intelligence Project of Henan, China (GJRC2018HS02).

Funding

Introduced International Intelligence Project of Henan, China, GJRC2018HS02, GJRC2018HS02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. built the databases and wrote the main manuscript text, J.S. revised the manuscript, C.L. proposed the methodology of research, J.L. supervised the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, M., Li, J., Li, C. et al. Effectiveness evaluation of different steel fibers on the shear strength of reinforced SFRC slender beams without web rebars. Sci Rep 14, 21249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71574-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71574-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advancing shear behavior prediction in SFRC beams: a comparative study of machine learning techniques

Discover Civil Engineering (2026)