Abstract

Women with a history of Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) have a high risk of developing Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in their future life. Lifestyle interventions are known to reduce this progression. The success of a lifestyle intervention mainly depends on its feasibility. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of a lifestyle intervention programme aimed to attenuate the development of T2DM in mothers with a history of GDM. This qualitative phenomenological study was carried out in selected Medical offices of Health (MOH) areas in Sri Lanka. Postpartum mothers with a history of GDM who have undergone a comprehensive, supervised lifestyle intervention program for 1 year, their family members, and public health midwives (PHM) were recruited for this study. Focus group discussions (FGD) were carried out with mothers and PHM while In-depth interviews (IDI) were conducted with family members. Framework analysis was used for the analysis of data. A total of 94 participants (45 mothers, 40 healthcare workers, and 9 family members) participated in FGDs and IDIs to provide feedback regarding the lifestyle intervention. Sixteen sub-themes emerged under the following four domains; (1) Feelings and experiences about the lifestyle intervention programme for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM (2) Facilitating factors (3) Barriers to implementation and (4) Suggestions for improvement. Spouse support and continued follow-up were major facilitating factors. The negative influence of healthcare workers was identified as a major barrier to appropriate implementation. All participants suggested introducing continuing education programmes to healthcare workers to update their knowledge. The spouse’s support and follow-ups played a pivotal role in terms of the success of the programme. Enhancing awareness of the healthcare workers is also essential to enhance the effectiveness of the programme. It is imperative to introduce a formal intervention programme for the postpartum management of mothers with a history of GDM. It is recommended that the GDM mothers should be followed up in the postpartum period and this should be included in the national postpartum care guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a global health concern. It is defined as a carbohydrate intolerance resulting in hyperglycemia, with onset or first recognition during pregnancy1. A recent meta-analysis suggested that women with a previous history of GDM have a 7.43-fold relative risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), 2 to 5-fold relative risk of metabolic syndrome, and a 1.7-fold risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those with a history of normoglycemic pregnancy2.

Lifestyle interventions are reported to delay or prevent the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by one-sixth time3 in women with a history of GDM. Diabetes Prevention Programme Research Group reported that the incidence of diabetes was reduced by 34% in 10 years with lifestyle interventions4. There are no reported national estimates of the prevalence of GDM in Sri Lanka. However, a recent Sri Lankan study has found that the prevalence of GDM in Gampaha district is 13.9%5 which is a 65.5% increase compared to the prevalence of GDM (8.4%) in Homagama MOH area Colombo district in 20046. Change in lifestyle during the postpartum period also prevents the recurrence of GDM, lower blood pressure, and triglyceride levels7, has positive effects on glycemic disturbances, and influences anthropometry by reducing weight8, Body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference of mothers9. Xiang et al.10 have confirmed that reducing insulin resistance either by a lifestyle-style intervention programme or by a pharmacological intervention will delay or prevent the development of T2DM in women with a history of GDM.

Early and effective postpartum lifestyle interventions are considered essential for preventing T2DM in women with a history of GDM11. Although women with GDM are considered high risk in terms of GDM recurrence and the risk of future diabetes, changing their lifestyle is challenging for most of them12. The majority of the women with GDM are found to understand the association between GDM and postpartum diabetes but do not perceive themselves as having an increased risk of developing diabetes13. Hence, the perception of risk is an important factor to motivate women to take up lifestyle modifications14. Further, the intervention programs should be intensive12 and culturally acceptable15.

Based on above knowledge we developed a intervention programme to attenuate the development of GDM to T2DM. During the intervention period of postnatal mothers16 we noticed that there were two groups of subjects according to their behavior. Firstly; the ‘dropout group’ included the subjects who completely left the program after some time. Second, the ‘adherence group’ who followed the program properly to fulfill the stipulated requirements and who as a result fared well than their counterparts. A previous study14 has also concluded that advice from healthcare providers alone is insufficient for women to achieve improvements in activity or diet.

Thus, stakeholders’ ideas and feedback on their experiences are vital to enhance compliance and reduce dropouts and drawbacks which will determine the success of a lifestyle intervention programme. Therefore, the general objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of the lifestyle intervention programme aimed to attenuate the development of T2DM in mothers with a history of GDM. The findings of this study will be a prime basis for healthcare policymakers to develop an effective and feasible lifestyle modification protocol for mothers with a history of GDM to attenuate their future risk.

Methods

Study design and setting

The study used a phenomenological qualitative research design to evaluate the feasibility of a lifestyle modification programme (summarized in Fig. 1) aimed at attenuating the development of T2DM in women with a history of GDM in three selected districts (Gampaha, Colombo, and Galle) of Sri Lanka.

The intervention was a tailored and culturally acceptable lifestyle modification programme for women with a history of GDM. The programme was designed based on literature and the findings of focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with stakeholders17,18 and had been validated by a panel of experts. The intervention protocols consisted mainly of two parts i.e. dietary and physical activity guidelines. The intervention was implemented in selected Medical Officer of Health (MOH) areas in selected districts in Sri Lanka. Individual counseling was provided for all the participating mothers (N = 50) at 6 weeks postpartum according to their BMI, health status, and mode of delivery. The mothers were followed up over the phone every 2 weeks and researchers visited their homes with area public health midwives at least once a month to supervise their progress. Blood investigations and anthropometric parameters were checked at baseline, at 6 months, and after 1 year of follow-up16.

Participants

Following categories of participants were selected for the study, using purposive sampling.

-

1.

Postpartum women with a history of GDM who have been recruited to undergo a lifestyle intervention programme for a period of 1 year. It was ensured that both the subjects who had completed the programme and those who dropped out due to various reasons were included.

-

2.

The family members of the above-mentioned postpartum women who had completed the programme and who dropped out due to various reasons.

-

3.

The healthcare workers [Public Health Midwives (PHM)] who have provided regular domiciliary care for the above-mentioned postpartum women

Data collection

Data were collected through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and In-depth interviews (IDIs) using semi-structured guides. The research team prepared three separate semi-structured guides to facilitate the FGDs and IDIs (Supplementary file 1). These guides were developed based on the findings of a literature review conducted under four domains namely, feelings about the lifestyle intervention, facilitating factors, barriers, and suggestions.

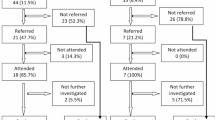

FGDs were carried out with the mothers and PHMs. Large samples from each group (mothers: n = 45, PHMs: n = 40) were used to ensure the diversity of the sample. A group of 10–15 purposefully selected mothers and PHMs from each district were invited for FGDs. FGDs were carried out in a comfortable room arranged especially for group discussions in the office of the PHMs' in the relevant MOH areas. They were conducted during evening hours without disturbing the clinic activities. A moderator facilitated the discussions, which lasted for 30 to 60 min with 6 -10 participants in one FGD. Data saturation was achieved after eight FGDs with mothers (two in Colombo, four in Gampaha, and two in Galle districts) and eight FGDs with healthcare workers (three in Colombo, three in Gampaha, and two in Galle districts). New information explored during initial discussions was further explored in-depth in subsequent FGDs to uncover hidden information and produce rich data.

In this study, IDIs were used to explore the perceptions and experiences of family members of both ‘adherence’ and ‘dropout’ groups regarding the lifestyle modification program. IDIs were used to ensure privacy and confidentiality as they may feel uncomfortable expressing their negative attitudes and feelings in front of others, and on the other hand free expression of ideas could cause data contamination19. IDIs were held between the moderator and the family members at their homes at a time convenient to them. The moderator facilitated all the interviews while the note-taker took notes. All interviews were double-recorded. Each IDI was conducted for 60–90 min. Altogether, nine IDIs were carried out with family members till the saturation point was achieved (three IDIs from each district). The new ideas generated by these interviews were added to the interviewer guide and explored further in subsequent interviews.

Data analysis

The framework approach was used for data analysis. Transcripts were prepared based on recorded data and notes of the note taker. Twenty-five transcripts were prepared (FGDs-16 and IDIs-9). Interesting segments of the transcripts were highlighted and the content of each passage was described in the left margin with a code. TDS and CJW independently coded the data of the 25 transcripts to minimize potential biases and discussed the common and uncommon code categories. Codes were compared and the differences were reviewed and resolved. The process of refining and applying was repeated until no new codes were generated. A working analytical framework was developed. A set of codes were prepared, each with a brief definition which formed the initial analytical framework. Four analytical frameworks were prepared separately based on the four domains. Then TDS and CJW re-coded all transcripts independently using the initial framework to identify similar codes which could be grouped. The final framework consisted of nine codes for the domain ‘feelings and experiences about the lifestyle intervention program’, twelve codes for the domain, ‘facilitating factors’, ten codes for the domain ‘barriers’, and eight codes for the domain ‘suggestions for improvement’. Themes were articulated and developed from the data set by reviewing the code.

In this study, a mixed method was used to develop the themes. Using the deductive approach, themes and codes were selected based on previous literature while in the inductive approach, themes were generated from the data set through open coding as suggested by Gale et al.20. Clusters of categories were gathered to develop a theme. Finally, the matrix was reviewed intensely to clarify the accuracy of the themes.

Ethical aspects

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura (Ref. No.04/17). Participants were invited and informed written consent was obtained, giving them the freedom to withdraw from the study at any point in time. They were ensured that their withdrawal from the study would not affect the usual care or any other benefits received by them. All the discussions were conducted in comfortable rooms at convenient times for them without disturbing personal or clinical activities. Administrative approval was taken from the MOH before conducting FGDs with PHMs.

Results

Summary of the socio-demographic data

Study subjects: A total of 94 subjects (45 mothers in eight FGDs, 40 healthcare workers in eight FGDs, and nine family members in nine IDIs) participated in the study. A group of mothers who adhered to the lifestyle intervention programme (n = 34) and another group who dropped out (n = 11) were purposefully recruited for the FGDs. The majority (n = 32) of the mothers were educated up to General Certificate of Education—Ordinary Level.

All 40 healthcare workers who participated in the study had a field experience of more than 10 years as PHMs. These PHMs visited the mothers during the entire study period.

The nine family members who participated in in-depth interviews included husbands (n = 3), mothers (n = 3), and mothers-in-law (n = 3) who lived with the postpartum mothers during the entire study period. Data obtained from all 94 subjects were taken for analysis.

Framework analysis

During framework analysis, altogether 16 themes emerged from the FGDs and IDIs conducted under four domains; namely, (1) Feelings and experiences about the lifestyle intervention programme for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM (2) facilitating factors (3) barriers and (4) suggestions for improvement.

Domain 1: Feelings and experiences about the lifestyle intervention programme for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM.

Three themes related to domain 1 emerged from semi-structured FGDs and IDIs. Three themes; namely, ‘practicality’, ‘essentiality’, and ‘effectiveness’ emerged from all three groups.

Theme 1: Practicality

In general, almost all mothers perceived the lifestyle modification programme positively. Mothers in the adherence group emphasized the importance of engaging in a lifestyle modification programme to ensure their future health.

In the words of a mother regarding the practicality of the program; "It is very easy to adhere to the programme. I did not need any additional effort, time or cost to carry it out properly”. “I had to do only minor alterations to my daily routine. Because I had to eat six small meals instead of three large meals, I didn’t feel hungry but felt comfortable. We learned how to convert our day-to-day activities into meaningful exercises. Everything was easy to carry out”.

Surprisingly, the mothers who dropped out also agreed that the programme was practical. “Though I was unable to do it properly due to my issues, this programme was practical. During the first few days, I engaged in it happily but I was unable to continue due to negative influences from my family”.

The PHMs also confirmed the ideas of the mothers. One PHM stated; “When I saw these guidelines, I felt that it is an easy programme to carry out since it suggests very few alterations to the usual lifestyle of mothers”. "Well, it is easy to do since it doesn’t need much time or money for it. When I visited the mothers I observed how they enjoy it".

The majority of family members reaffirmed the mothers’ views on practicality and stated below is how a husband expressed it in his own words; "I read the guide completely and clarified the queries from the researchers. I was surprised to know that there is nothing much to change. I encouraged her to adhere to it”.

However, some family members did not agree that the programme is practical. As one mother-in-law stated; "It is not enough to eat small meals when you breastfeed the baby. A Mother after childbirth should have meals like a king".

Agreeing with the above, the others’ views were, “It is not easy to prepare food when they have children. They have to give priority to the child and eat what they have to fill the stomach". “It is not good to involve in strenuous activities after childbirth as it can affect the future health of both the mother and the baby".

Theme 2: Essentiality

Mothers in the adherence group believed that this programme is essential to protect them from the risk of diabetes. As one mother stated; "It is very important to introduce a programme like this. We learned a lot of things about our present health and the future risk of diabetes. This is an essential programme that should be taught to all mothers after childbirth. I am going to educate my friends also about this".

Healthcare workers also agreed with these statements. One PHM said; "It is vital to introduce a programme like this to all mothers with GDM. Otherwise most of them will end up having diabetes".

Family members also agreed with this view. As one husband stated; "Actually, if simple programs like this can reduce the future risk of diabetes in these mothers, the government should introduce these in a more organized manner".

Theme 3: Effectiveness

Mothers in the adherence group expressed their happiness regarding the outcomes they achieved by following the programme. One mother stated; "Look at me, and then you can understand how effective the programme is. I have reduced by eight kilograms and achieved my pre-pregnancy weight within 1 year because of this programme. In my previous pregnancy, I struggled to reduce my weight. But this time, my weight was reduced without much effort". "The programme has helped me to get into shape quickly. My husband is also happy with the way I look now. This makes me happy".

Some mothers in the dropout group expressed their regret for not continuing the programme. "I feel so foolish. I didn't take the programme seriously and I didn't adhere to it. My sugar level is increased now and I am advised to meet a specialist doctor".

Healthcare workers agreed with these statements. "Yes, I think it is very effective. I can see the changes in the mothers who adhered to it properly". "This programme is like magic. Simple things have given huge results".

Family members also confirmed these ideas; especially some husbands had very optimistic feelings about this programme. In the words of a husband regarding the effectiveness of the programme: "Previous time I sent my wife to a gym to reduce her weight but it didn’t work out for us. This time she reduced weight within a year without much effort. I am really happy about it".

Domain 2: Facilitating factors

Six themes related to domain 2 emerged from the FGDs and IDIs. Two themes namely, ‘being monitored’ and ‘spouse’s support’ emerged from all three groups. ‘Desire for being healthy and beautiful’ emerged from healthcare workers and family members while ‘knowing the risk of future diabetes’ emerged from mothers and healthcare workers. The themes, ‘self-responsibility’ and ‘decision-making ability’ surfaced solely from FGDs with mothers.

Theme 1: Being monitored

Mothers stated that regular follow-up visits and telephone calls were the major facilitating factors for the success of this programme. Those visits and calls motivated them to continue with the programme. In the own words of mothers; "Sometimes I felt lazy to eat and engage in physical activities as instructed. But when you called me to remind, I felt obliged to carry on as recommended”. "Your visit is like an alarm. I have times that I wanted to withdraw from the programme but your visits and calls encouraged me to continue with it”.

PHMs also agreed with the ideas of the mothers and they confirmed that they observed changes in mothers’ attitudes and behaviors due to this regular, dedicated follow-up. "When the mothers attend the well-baby clinic, we ask them about the progress of the programme. We felt that they didn't dare to give it up because of the close monitoring and follow-up".

All family members also believed that monitoring is very important. In the own words of a mother’s mother; "My daughter was very enthusiastic to engage in this programme and waits for a call from you to discuss her concerns”.

Theme 2: Spouse’s support

All mothers in the adherence group emphasized the importance of their husbands' support to carry on the programme properly. As mothers stated, the interest and concern of the husband regarding the wife's health is very important. One mother noted; "My husband always encouraged me to engage in the programme properly. He visited the PHM to clarify my concerns regarding it. Every evening he used to ask me about my progress".

Another mother stated; "My husband always supports me mentally and physically and looks after my little one when I do my exercises".

PHMs confirmed that the spouse’s support was the major facilitator among all others as the husband is the closest to a woman after marriage. PHMs were happy that a majority of the husbands had positive feelings about this programme and visited their offices to improve their awareness about the programme. In PHM's own words; "Some fathers come to our office and ask a lot of questions about the programme. It is hard to believe the amount of interest they have in it".

Family members, especially the mother’s mother confirmed this statement. "My son-in-law was very interested in this programme. He did not allow us to give high-carb foods to my daughter although we believed that it was not possible to produce milk without high-carb food. He also gave up his favorite sweetmeats to protect my daughter's health".

Theme 3: Desire for being healthy and beautiful

Another idea expressed by healthcare workers was that mothers desired to be healthy and beautiful. Since the majority of mothers are young, they like to be attractive. As one PHM expressed it; "The programme helps them to maintain their body weight without interfering with breastfeeding. These days women are keen to maintain shape”.

Family members also confirmed this idea. In the own words of a mother’s mother; "After the delivery of her first baby, my daughter was not happy as she was overweight and had a large tummy even after 1 year. But this time, she was lucky to be selected for this programme as she managed to reduce her weight and get into shape soon”.

Theme 4: Knowing the risk of future diabetes

Education played a major role in motivating the mothers to adhere to the lifestyle intervention programme. The mothers in the adherence group indicated how this knowledge helped them to carry out the programme meaningfully. As one mother indicated; "Knowing about the risk of me being a diabetic made me anxious and this feeling encouraged me to adhere to the programme. It is better to prevent it rather than staying till you get it”.

Healthcare workers also confirmed the importance of enhancing the awareness of mothers about their future risk of T2DM to increase their motivation to adhere to the programme. "After knowing their risk, mothers got highly motivated to continue with this programme actively".

Theme 5: Self-responsibility

The majority of mothers in the adherence group believed that they are responsible for their destiny and it can be changed according to their will. Therefore, they think they should take charge of their future health. In the words of mothers; "This programme is very good. It adds value to me and I feel responsible about my health". "I am the person who should take responsibility for what happens tomorrow. Neither my husband nor my family can be accountable for my life. So, I decided to follow this programme with passion on behalf of my family". "In my point of view if I can control my mind, I can control my mouth. If both the mind and mouth are mine, why can't I control them properly?".

Theme 6: Decision-making ability (Self-autonomy)

Mothers indicated that the programme has given them authority to make decisions about their food and activities without much interference from others in the family. One mother said; "Nobody in my family forces me to eat anything because they know about the programme. Since I cook for my family, I decide what to prepare".

Another mother stated; "In my previous pregnancy, my mother and grandmother used to tell me to eat a lot of starchy food to increase the amount of milk production. As a result, I was very fat even 1 year after the delivery. But now, after getting to know about this programme, they allow me to decide on what I eat. Although I limited my calories, I had enough milk for the baby”.

Domain 3: Barriers

Five themes related to domain three emerged from the FGDs and IDIs. Three themes; namely, 'negative influences from healthcare workers', 'social influence', and 'prioritizing competing demands over one's own health' emerged from all three groups, whereas 'lack of self-interest' emerged from mothers.' Uncertainty about the future was identified from FGDs with PHMs.

Theme 1: Negative influences from healthcare workers

The family doctor was the closest healthcare worker of some mothers and they tend to believe only the advice coming from him. In the own words of mothers in the dropout group, "I met my family doctor with my husband because I had less milk for the baby. When I told about the change in my lifestyle, he advised me to discontinue the programme. He didn’t have much faith in it’’. "My family doctor has advised me to get adequate rest because I am breastfeeding. Therefore, I did not want to engage in this programme as it involved physical activity”. "My PHM told me that I don't have diabetes now and therefore I am completely healthy. So why should I spend time in changing my lifestyle?”.

Healthcare workers also confirmed this idea during FGDs. "Although we made the mothers aware of this programme, we have noticed that some mothers just listen to their doctors, disregarding any other advice. Some doctors have even advised them to eat high-carb food to increase milk production”.

The majority of family members also supported this idea. They feel their family doctor is the most accurate. In a husband's own words; "Family doctor is the person we knew from our childhood. So, what he tells us is for our good. These lifestyle changes are not good for the baby’s health".

Theme 2: Social influence

Most mothers indicated that negative influences from peers, workplace, neighbors, and environment affect their inner motivation and demoralize them to adhere to the programme. Yet, interestingly, the mothers in the ‘adherence group’ have tried to overcome these feelings by discussing them with relevant groups. One mother in the adherence group stated; "I work as a management assistant in an office. When I go to the office, I have lunch with my friends. Because I can't refuse the food they share, I reduce my portion size during dinner and try to balance my daily calorie requirement as recommended. Because I feel very tired to engage in exercises when I come home, I get down one bus halt ahead and walk that distance to get my required exercises”.

But unfortunately, the mothers in the ‘dropout’ group were not able to overcome these barriers. "My friends in the office who have children think they know everything about postpartum care by their previous experiences. Although I have tried explaining to them about this programme, it's very difficult to convince them. They do not allow me to reduce the amount I eat, especially the amount of rice in the meal”. "When I try to do exercises, my mother-in-law thinks I am crazy. She thinks that only teenagers should engage in exercises”.

PHMs also confirmed their ideas and thought that these women are in a helpless state. "That is true. One day when I visited a mother at her home, her mother-in-law blamed me as well. She told me that in those days they ate properly after the delivery of a baby without thinking about the body weight or shape”.

Theme 3: Prioritizing competing demands over one's own health

All mothers in the ‘adherence group’ as well as in the ‘drop-out group’ believed that nothing is more important than the well-being of their children. They think they have to fulfill all the requirements of their family before thinking about themselves.

As one mother stated; "Though I like this programme very much and want to engage in it properly, I have no time to spare when my child becomes sick. I don't have time or peace of mind to think about myself". Other statements made by mothers are; "My mother-in-law is bedridden and I have two children to care for. Although I am interested in this programme, how can I find time for it? I have to fulfill their requirements first before I think of myself".

Healthcare workers also confirmed these ideas. "Some mothers were extremely willing to be a part of this programme but they had to look into so many family needs. Once they get involved in all these, they don’t have the time or the energy to do something for them".

Family members looked at this situation differently. One husband stated; "Our baby is small. He is the most important member of our family. My wife is healthy now and I don’t think we should waste time on her exercises". One mother-in-law expressed; "I am also a mother. Mothers cannot think selfishly about themselves. Her duty is towards her family. There’s nothing wrong in making sacrifices on behalf of the family. Is there anything wrong in it"?

Theme 4: Lack of self-interest

Mothers in the ‘dropout group’ highlighted their lack of interest in the programme. One mother stated; "When the baby was inside, we felt it is essential to listen to you as we need healthy babies. I can remember doing some exercises, taught by my PHM to make the delivery easy. But now, I am not worried about these things and I don’t have any interest to do things extra".

Theme 5: Uncertainty about the future

This theme emerged exclusively from PHMs. They perceived that the young generation does not have a plan for the future. They only think about today but not about tomorrow.

In the own words of PHMs; "Some mothers don’t think about their future. They ask ‘What is the use of doing all these things, when we do not know what happens to us even tomorrow? Hence, they think it is better to enjoy their lives today without thinking about the future risks".

Domain 4: Suggestions for improvement

Four themes related to domain 4 emerged from the FGDs and IDIs. Three themes; namely, 'compulsory continuous follow up of postpartum mothers', 'awareness through television and social media', and 'continuous professional development of healthcare workers' emerged from all three groups. 'Awareness starting at the school level' surfaced only from FGDs with mothers and healthcare workers.

Theme 1: Compulsory continuous follow-up of postpartum mothers

All mothers, healthcare workers, and family members stressed the importance of continuing the follow-up of these mothers after the delivery for an extended period.

One mother expressed it in her own words; "After the baby is delivered, we don't have time to think about ourselves but if you are behind us like in this programme, we automatically start allocating some time for us. It is better if you can continue this type of programme for at least 5 years after the delivery”. "I suggest that mothers should be enrolled in a programme like this during the latter part of pregnancy so that they will be prepared to start it as soon as possible when they are fit".

PHMs also agreed to the ideas of the mothers but they highlighted some special problems regarding the practicality. "This program was successful because of the close monitoring and follow up. But the current staff is not enough if the government introduces such programmes for all mothers”.

Family members confirmed the idea further. One husband reported; "My wife did it because of your continuous support. If you just introduced it and left it to us to continue, I am sure we would have forgotten it in a few days and got back to our previous routine”.

Theme 2: Awareness through television and social media

Social media is a major factor influencing the lives of people currently. The mothers believed that this influence can be used in a better way to enhance the awareness of health risks, complications, and prevention of diseases. They feel that the entire family can benefit from this.

One mother stated; "We all watch television during our leisure. So, if these health messages can come as small alerts, it will be more effective than all other methods". "Social media, especially ‘Facebook’ is very popular among us. It is good if you can carry these health tips through Facebook”.

Healthcare workers also refined the ideas of the mothers and expressed; "Mothers are more likely to believe what appears on television than us telling them. It is better if you can display these ideas as health alerts during prime time, like just before news".

Family members believed that whatever information shared through social media should come regularly to make a change in anybody. Increasing the awareness of other family members along with the mothers was highlighted as an added advantage of this mode of communication.

One husband expressed it in his own words; "Look, now the government has used the radio and television to increase awareness in people about the consequences of tobacco use. It is better if you also can display an inspiring message during news time".

Theme 3: Continuous professional development of healthcare workers

The knowledge of healthcare workers should be regularly updated to achieve the maximum benefits of a healthcare programme. Varying inputs from healthcare workers cause confusion among mothers and hinder the success of the programme.

As stated in the own words of mothers; "It is not easy to understand what is correct and what is wrong as each of you tell us things that are slightly different. If all of you tell us the same thing, we will listen to you and learn from you”.

PHMs confirmed the ideas of the mothers; "Actually, we also didn’t know the relationship between GDM and DM till we got involved with this programme. It’s very pathetic that most of us don’t know to answer some of the questions patients ask. So, it is very important to have regular programmes to update our knowledge”.

The family members approved these statements and one husband stated; "Not only this. We face a lot of confusion even when we take our baby to the hospital. The doctors and nurses tell us one thing and the midwife who visits us tells us something different. I feel there is a lack of education somewhere. It is good if authorities take this seriously and plan some corrective measures”.

Theme 4: Awareness starting at the school level

Both mothers and healthcare workers expressed the importance of introducing some awareness regarding these health issues at a young age. They thought that teenage girls who are going to be mothers someday would grasp these ideas more effectively.

One mother stated; "We get a lot of ideas and opinions from our relations, friends, and neighbors in addition to what we get from you. Sometimes we get confused and we do not know what to believe. If we had a clear idea based on scientific information from the beginning, we would have faced this with ease".

A PHM also endorsed this idea strongly. In her own words; "It is so hard to change mature minds. It would have been easy if these things are introduced to them when they were young. If we can have programmes to educate late teens, they will take these health messages for their future".

Discussion

This qualitative phenomenological study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of the newly introduced lifestyle intervention programme for mothers who had a history of GDM. The perceptions of mothers, healthcare workers, and family members were explored through FGDs and IDIs under four domains to upgrade the robustness of the programme. The domains included ‘feelings and experiences about the introduced lifestyle intervention programme for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM’, ‘facilitating factors’, ‘barriers’, and ‘suggestions for improvement’. The framework method, which is considered the best method to analyze data that covers similar topics20, was used to analyze the data.

Feelings and experiences about the introduced lifestyle intervention programme for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM.

In general, all mothers in both adherence and dropout groups, PHMs, and family members highlighted the essentiality and effectiveness of the introduced programme. The mothers in the adherence group entertained the positive consequences that they experienced by following this programme appropriately, while the dropouts regretted their failure. PHMs highlighted the observed positive mental and physical changes of these mothers. Interestingly, husbands and family members also had positive feelings about this programme and they have shown a growing interest and trust in the programme due to these visible changes in mothers. As per the views of PHMs and family members, mothers enjoyed this program mainly because they are generally young and they have a liking to be attractive. It appears that mothers' inner interest has become a strong facilitating factor in terms of success. Based on the noticeable changes they experienced, all the participants emphasized the essentiality of the program for all postpartum mothers who have had GDM in their index pregnancies. Meanwhile, healthcare practitioners highlighted the essentiality of a similar programme to reduce the future burden of T2DM.

The mothers in the adherence group accepted the practicality of the programme in the same way as healthcare workers. They acknowledged that the programme included specific, personalized guidelines. In agreement with this, in a qualitative study conducted among white women in UK, Lie, and co-researchers21 have also noted that mothers abide by a lifestyle intervention programme if it is feasible, individualized, and addresses the childcare demands. Interestingly, mothers in the dropout group also acknowledged the practicality of the programme, though they were unable to continue it due to various internal and external factors. However, some family members, especially the elderly women in the family, strongly disagreed with its practicality due to certain personal beliefs and norms. It may be attributable to the unwillingness of some individuals to accept novel concepts based on scientific grounds.

Facilitating factors

In this study, spouse’s support was identified as the major facilitating factor by all three study groups. This support has been described by previous literature as emotional22 and instrumental (such as physical, material, or financial) support23. Hence, it acts as one of the major motivating factors for mothers24. In this study, the husband's interest has been enhanced with the knowledge gained and visible results of the programme. Lie et al.21 have also proven that husbands' attitudes and awareness of the diabetes risk are the major influential tools in diabetes prevention among GDM mothers. Husbands in our study looked after the children while their wives engaged in exercises and sometimes they accompanied the wife during exercises. Companionship is a very important motivating factor because women withdraw from the exercises due to loss of companionship23. In the present study, as in a previous study in France25, the spouse as well has changed their food choices in some instances and consumed food according to dietary guidelines provided to their wives during the intervention. Due to this dedication, mothers have overcome the household taste preference barrier which is reported in the literature14.

Continued follow-up was another facilitator which surfaced from all three groups. Our findings are in steady agreement with studies worldwide. Individual counseling24,26, close monitoring, reminders through phone27, and easy access to educators were more beneficial than an unaccompanied health education session. In addition, ongoing support21,24, continuous visits, and clinics28 have in turn been shown as hidden facilitators in other settings. Similar to this study, in another study carried out among postpartum mothers in Canada29, the continued and systematic follow-up was identified as a facilitator because it was shown to motivate the mothers to adhere firmly and freely to the programme.

In contrast, Wennberg and colleagues30 have concluded that continued monitoring by a midwife has created stress and pressure among twenty-three mid-pregnancy participants in Sweden and these women perceived it as a negative influence on their success. The observed difference may have occurred due to the timing of the studies.

As suggested by Lie et al.21, during the entire study period of the present study, the mothers were provided with constant external motivation through follow-up phone calls, home visits, and other forms of continued support. In this study, the fact that healthcare workers reached the mothers to provide routine domiciliary care was an added advantage since traveling to seek health care during the early postpartum period is a hassle to the mother27. As evidenced by previous studies27, this would have enhanced the compliance of the mothers.

According to the views of the mothers, they have gained knowledge regarding their future risk of T2DM and strategies for prevention through this programme, which they have never learned earlier during the antenatal period or any other time throughout their life. It is reported that adequate knowledge about GDM and T2DM may help to overcome barriers and enhance mothers’ health behaviors31. Risk awareness has become one of the major facilitating factors in this study. As reported in previous literature, risk awareness directed towards anxiety may be the strongest reason to increase interest in lifestyle modification21,29 which might create a strong intention to adopt a healthy lifestyle14. Furthermore, Collier et al.24 reported that low-risk perception is associated with a lack of intention to change behaviours. A previous study suggests that after gaining knowledge, mothers have understood that they are the only responsible person for their future health30. It has given them value and enhanced their passion and self-discipline. Hence, it seems that gaining knowledge has become an inner motivating factor and a hidden facilitator for success.

The lifestyle intervention programme was able to enhance the self-autonomy and decision-making ability of the mothers. Decision-making ability gives mothers a sense of control in taking decisions that would support their healthy future32. However, Kelsey et al.33 have found through FGDs that the decision-making ability itself is not enough to change their bahaviour, especially if they have a lack of interest.

Barriers

A major barrier identified in this study was the negative influence of healthcare workers. In the Sri Lankan setting, people believe in their closest healthcare worker for guidance on health matters. Beliefs about GDM or T2DM in healthcare workers influence the health beliefs of the patient and the family34. Mothers claimed that sometimes they were confused due to varying advice coming from their family doctor, the area midwife, and the research team. Contradictory information from various sources is known to confuse patients30. Family members of the study participants mainly believed in the guidance provided by the healthcare worker closest to them.

In general, the healthcare workers in the present study were aware that women with GDM are at high risk of developing T2DM, however, their knowledge on effective postpartum follow-up was inadequate. Other studies also have shown that the majority of healthcare practitioners did not have specific and updated knowledge about postpartum practices in GDM28,30 due to a lack of clear guidance, protocols, or national policy and continuing education programmes to update their knowledge3. PHMs in this study did not have much knowledge about the postpartum management of mothers with GDM to attenuate the progression of GDM to T2DM until they became a part of this programme. They expressed their situation honestly and showed a keen interest to keep their knowledge up-to-date. Hence, as Morrison and co-researchers28 suggested, it is a timely requirement to introduce a compulsory continuing education programme to all healthcare workers, which was confirmed by our FGD and IDI findings.

Inputs from the immediate surroundings exert an important impact on individuals, facilitating or hindering health behaviors and it is proven that support from family21, especially from female members23 is very important for the success of a programme. However, in this study, it was evident that the mothers did not get the fullest support from the family in their lifestyle changes, although it was readily available for child care. As per the Sri Lankan cultural norms, mothers stay in their ancestral homes for a period of 3 months after childbirth. Therefore, they generally abide by their elders' practices and beliefs, especially the guidance that comes from the elderly females of the family. A qualitative study with Latino women has identified the influence coming from the mother-in-law during pregnancy and the postpartum period as a barrier to implementing a proper nutrition and exercise programme23.

It is proven that a holistic approach is important to overcome social barriers and get the optimal benefits of a programme. After careful exploration, it was understood that in addition to family members, the peers, and neighbors had also influenced the mothers regarding the intervention based on their cultural and social beliefs. Thornton and colleagues in 200623 also observed that neighbors influenced women’s activities based on cultural and social norms. Thornton et al.23 recommend considering friends and peers together as one of the most inspiring close networks of a mother, despite their cultural and geographical differences. However, mothers in the adherence group have positively taken these influences and shared their knowledge with them. Increasing awareness of mothers helps them to overcome social barriers.

It is very important to get the support of society for the success of intervention because it is a known positive motivator for women24. The present study and a previous qualitative study in Australia with pregnant mothers28 revealed the importance of introducing community education programmes to fight against the fatalism of society and to enhance optimistic feelings towards lifestyle interventions. Sadly, in the present study, even mothers with a strong family history of diabetes were not concerned about their future risk of the disease. It was found that they have only a vague idea about the disease. As reported in previous literature, not only mothers with a family history of T2DM but also mothers with the experience of previous GDM do not have any sense of future risk21. It seems like diabetes has become generalized among them and their social groups. Hence, it is very important to plan strong community education programmes to increase awareness.

Previous research has also shown that mothers tend to prioritize the needs of the baby and the others in the family over their health21,24 and this, in turn, becomes a barrier to the success of an intervention programme. In the current study, though some mothers were willing to adhere to the interventions properly, they were unable to continue due to unavoidable family commitments as in other settings29.

It is reported that mothers have a powerful motivation regarding their health during the antenatal period to optimize the health of the unborn baby16,21. Hence, they adhere to guidelines provided to them during the antenatal period till the baby is born. This problem becomes more serious as there are no strict guidelines and intense support systems for postpartum mothers. The literature reveals that once these mothers get their blood glucose values back to normal, they believe that they are healthy enough to drop out from the postpartum follow-up programmes28 as they need to be considered normal17. Hence, it appears as if they have completely forgotten their GDM history till they face consequences in later life.

Suggestions for improvement

In general, all three groups participating in the present study suggested continuing follow-up and ensuring closer monitoring of mothers during the first postpartum year. Several quantitative studies35,36 which introduced lifestyle interventions to postpartum mothers with a history of GDM, including the subsequent components of this study, have proven the effectiveness of continuous follow-up and intense support in attenuating the progression of GDM to T2DM during the postpartum period. A study conducted in Canada using semi-structured interviews with postpartum mothers also identified that continuous support and education were important to keep the mothers in line with a healthy lifestyle29. We suggest that continued follow-up and regular monitoring of mothers with a history of GDM should be introduced in an organized manner to the national healthcare system to reduce the future health burden of diabetes and its complications. However, the healthcare workers in this study agreed with what is emphasized in a study done in the UK37 regarding the difficulties in implementing such programmes and continued follow-up due to the shortage of community health workers. This is a common problem in many other countries including India38. Hence, the authorities should take the initiative to search for alternative ways to overcome this issue. One major suggestion which surfaced during discussions and interviews was to use social media such as TV commercials, display boards, videos, and social media such as Facebook, etc. to enhance public awareness. Social media reaches mothers easily, overcoming the barriers of geographical and physical nature39. Telecasting video clips or small dramas in antenatal clinics would be helpful to convey these messages to the mothers and their family members easily.

Unawareness of the health care workers is considered a main constraint to implementing intervention programmes in the Sri Lankan setting. Furthermore, a recent Sri Lankan study found that the unawareness of clinicians and other healthcare workers about long-term complications of GDM may have jeopardized the screening and follow-up of GDM mothers40. It seems that continuing education programmes are vital to all healthcare workers to eliminate the future diabetes risk in Sri Lanka. Another suggestion that surfaced during discussions and interviews was to start an awareness programme for school children. As revealed by this study, school is the best place to provide a holistic view of health. It might be easy to discuss physical, social, cultural, mental, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions of health with school children with open minds.

This study has many strengths such as the high response rate and active participation of all stakeholders. This has helped the investigators to realize the actual situation holistically. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the results may have been influenced by subject bias. Women and healthcare workers who participated in this part of the study have had associations with the study team for 1 year during the prospective component. Hence their perceptions may have been influenced by this relationship. However, we believe that our semi-structured script for interviews and discussions would have minimized this negative effect and bias. As our sample of healthcare workers was recruited from three districts in Sri Lanka, these findings might not reflect the opinions and experiences of healthcare workers from other parts of the country.

Conclusion

Spouse’s support and continued follow-up played a pivotal role in terms of the success of the lifestyle intervention programme. Furthermore, awareness of the future T2DM risk, self-responsibility, the decision-making ability of mothers, and the desire to be healthy and attractive facilitated adherence to the programme. Negative reinforcement of the healthcare workers who are in close contact with the mothers was identified as one of the major barriers. Social influence, prioritizing childcare demands over one's health, lack of self-interest, and uncertainty about the future were identified as other barriers. The healthcare workers should be updated regarding the risk of T2DM in mothers with a history of GDM and postpartum management to attenuate the progression of GDM to T2DM. Further, it is recommended that the GDM mothers should be followed up in the postpartum period and this to be included in the national GDM care guidelines.

Implementations

The findings of this study are expected to enhance the quality of future lifestyle intervention protocols and facilitate the development of other preventive strategies for postpartum mothers with a history of GDM.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- FGDs:

-

Focus group discussion

- Fig.:

-

Figure

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- IDI:

-

In depth interviews

- MOH:

-

Medical officer of health

- PHM:

-

Public health midwife

- T2DM:

-

Type two diabetes mellitus

References

Metzger, B. E., Coustan, D. R., Organizing Committee. Summary and recommendations of the fourth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 21, 161 (1998).

Verier-Mine, O. Outcomes in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Literature review. Diabetes Metab. 6, 595–616 (2010).

Stuebe, A. et al. Barriers to follow-up for women with a history of gestational diabetes. Am. J. Perinatol. 27(09), 705–710 (2010).

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 374, 1677–1686 (2009).

Sudasinghe, B. H., Ginige, P. S. & Wijeyaratne, C. N. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in a Suburban District in Sri Lanka: A population based study. Ceylon Med. J. 61, 4 (2016).

Ginege, P. S. Prevalence and pregnancy outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in Homagama DDHS area and validation of selected screening methods to detect GDM. (2004).

Moon, J. H., Kwak, S. H. & Jang, H. C. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Korean J. Intern. Med. 32, 26 (2017).

Ferrara, A. et al. The comparative effectiveness of diabetes prevention strategies to reduce postpartum weight retention in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: The Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 1(39), 65–74 (2016).

Goveia, P. et al. Lifestyle intervention for the prevention of diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 5(9), 583 (2018).

Xiang, A. H. et al. Longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and beta cell function between women with and without a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 56, 2753–2760 (2013).

Ehrlich, S. F. et al. Post-partum weight loss and glucose metabolism in women with gestational diabetes: The DEBI Study. Diabet. Med. 31(7), 862–867 (2014).

Stage, E., Ronneby, H. & Damm, P. Lifestyle change after gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 63(1), 67–72 (2004).

Nielsen, J. H., Olesen, C. R., Kristiansen, T. M., Bak, C. K. & Overgaard, C. Reasons for women’s non-participation in follow-up screening after gestational diabetes. Women Birth. 28(4), e157–e163 (2015).

Kim, C. et al. Risk perception for diabetes among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 30(9), 2281–2286 (2007).

Carolan, M., Gill, G. K. & Steele, C. Women’s experiences of factors that facilitate or inhibit gestational diabetes self-management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 12, 1–2 (2012).

Sundarapperuma, T. D., Katulanda, P., Wijesinghe, C. J., Hettiarachchi, P. & Wasalathanthri, S. The impact of a culturally adapted lifestyle intervention on the glycaemic profile of mothers with GDM one year after delivery—a community-based, cluster randomized trial in Sri Lanka. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24(1), 104 (2024).

Sundarapperuma, T. D., Wijesinghe, C. J., Hettiarachchi, P. & Wasalathanthri, S. Perceptions on diet and dietary modifications during postpartum period aiming at attenuating progression of GDM to DM: A qualitative study of mothers and health care workers. J. Diabetes Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6459364 (2018).

Sundarapperuma, T. D., Wijesinghe, C. J., Hettiarachchi, P. & Wasalathanthri, S. Perceptions of mothers with gestational diabetes and their healthcare workers on postpartum physical activity to attenuate progression of gestational diabetes to diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study. Natl. Med. J. India 37(1), 5–8 (2024).

DiCicco-Bloom, B. & Crabtree, B. F. The qualitative research interview. Med. Educ. 40(4), 314–321 (2006).

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S. & Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13(1), 1–8 (2013).

Lie, M. L. et al. Preventing type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: Women’s experiences and implications for diabetes prevention interventions. Diabet. Med. 30(8), 986–993 (2013).

Symons Downs, D. & Ulbrecht, J. Gestational diabetes and exercise beliefs: An elicitation study. Diabetes Care 29(2), 236–240 (2006).

Thornton, P. L. et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: The role of social support. Matern. Child Health J. 10, 95–104 (2006).

Collier, S. A. et al. A qualitative study of perceived barriers to management of diabetes among women with a history of diabetes during pregnancy. J. Women’s Health. 20(9), 1333–1339 (2011).

Krompa, K., Sebbah, S., Baudry, C., Cosson, E. & Bihan, H. Postpartum lifestyle modifications for women with gestational diabetes: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1(252), 105–111 (2020).

Kim, C. et al. Preventive counseling among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 30(10), 2489–2495 (2007).

Zehle, K. et al. Psychosocial factors related to diet among women with recent gestational diabetes opportunities for intervention. Diabetes Educ. 34(5), 807–814 (2008).

Morrison, M. K., Lowe, J. M. & Collins, C. E. Australian women’s experiences of living with gestational diabetes. Women Birth. 27(1), 52–57 (2014).

Evans, M. K., Patrick, L. J. & Wellington, C. M. Health behaviours of postpartum women with a history of gestational diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes. 34(3), 227–232 (2010).

Wennberg, A. L., Lundqvist, A., Högberg, U., Sandström, H. & Hamberg, K. Women’s experiences of dietary advice and dietary changes during pregnancy. Midwifery. 29(9), 1027–1034 (2013).

Tang, J. W. et al. Perspectives on prevention of type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: A qualitative study of Hispanic, African-American and White women. Matern. Child Health J. 19, 1526–1534 (2015).

Harrison, M. J., Kushner, K. E., Benzies, K., Rempel, G. & Kimak, C. Women’s satisfaction with their involvement in health care decisions during a high-risk pregnancy. Birth. 30(2), 109–115 (2003).

Kelsey, K. S. et al. Social support as a predictor of dietary change in a low-income population. Health Educ. Res. 11(3), 383–395 (1996).

Hjelm, K., Bard, K. & Apelqvist, J. Gestational diabetes: Prospective interview-study of the developing beliefs about health, illness and health care in migrant women. J. Clin. Nurs. 21(21–22), 3244–3256 (2012).

O’Reilly, S. L. et al. Mothers after Gestational Diabetes in Australia (MAGDA): A randomised controlled trial of a postnatal diabetes prevention program. PLoS Med. 13(7), e1002092 (2016).

Huvinen, E. et al. Effects of a lifestyle intervention during pregnancy and first postpartum year: Findings from the RADIEL study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103(4), 1669–1677 (2018).

Moore, A. P., D’Amico, M. I., Cooper, N. A. & Thangaratinam, S. Designing a lifestyle intervention to reduce risk of type 2 diabetes in postpartum mothers following gestational diabetes: An online survey with mothers and health professionals. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1(220), 106–112 (2018).

Nielsen, K. K., de Courten, M. & Kapur, A. Health system and societal barriers for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) services-lessons from World Diabetes Foundation supported GDM projects. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights. 12, 1 (2012).

Welch, V., Petkovic, J., Pardo, J. P., Rader, T. & Tugwell, P. Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: An overview of reviews. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Canada Res. Policy Pract. 36(4), 63 (2016).

Herath, H., Herath, R. & Wickremasinghe, R. Gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of type 2 diabetes 10 years after the index pregnancy in Sri Lankan women—A community based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 12(6), e0179647 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful to all the participants of the study.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka (ASP/06/RE/MED/2015/44).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TDS contributed to conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript drafting and revision. PH guided manuscript drafting. SW contributed to the conceptualization and manuscript drafting and CJW also contributed to the conceptualization, guided qualitative data analysis, and manuscript drafting. All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura (ERC No.04/17), Sri Lanka. All methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed written consent was obtained from the selected subjects for the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sundarapperuma, T.D., Hettiarachchi, P., Wasalathanthri, S. et al. Perspectives of stakeholders on the implementation of a dietary and exercise intervention for postpartum mothers with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): a community-based qualitative study. Sci Rep 14, 20780 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71587-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71587-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

“To be honest, no one cares”: an ethnographic study of postpartum perceptions and practices after gestational diabetes in Vietnam

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2025)