Abstract

Immunodeficiency 11B with atopic dermatitis (IMD11B, OMIM:617638) is rare primary immunodeficiency disease caused by germline dominant negative (DN) mutations in the CARD11 gene. Affected patients present with immune dysfunction, recurrent infections and atopic dermatitis. In this study, we sought to identify and characterize the genetic variant in one patient with periodic fever, recurrent infections, and eczema. Trio whole-exome sequencing (WES) was employed in this patient and her parents, and Sanger sequencing validated the potential pathogenic variant. In vitro functional study was performed to evaluate the pathogenicity of genetic variant identified. A very rare missense mutation (c.2324C > T, p.S775L) in CARD11 gene (NM_032415) was identified by WES in the patient but not her parents. Luciferase reporter assays and co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated mutation exerts a dominant-interfering effect on wild-type CARD11, inhibiting the activity of NF-κB. RNA sequencing analysis also confirmed that mutant CARD11 inhibited down-stream transcriptional activity of NF-κB. A review of literature doesn’t found significant genotype–phenotype correlation. We identified a vary rare DN CARD11 mutation, expanding the genetic and phenotypic spectrum of CARD11.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 11(CARD11), also known as caspase recruitment domain membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein 1 (CARMA1), is a scaffolding protein and expressed in hematopoietic tissue and lymphocytes1. CARD11 interacts with BCL10 and MALT1 to assemble the CARD11-BCL10-MALT1 (CBM) complex and the assembly of CBM is an essential step in the activation of the IκB kinase (IκK)/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) through B-cell and T-cell receptors2,3,4.

Human CARD11 consists of 1154 amino asides and contains multiple functional domains, including a N-terminal CARD (1–110), LATCH (112–130), coiled-coil (130–449), autoinhibitory and a C-terminal MAGUK (667–1140) domains. MAGUK is comprised of PDZ, L3, SH3 and GUK subdomains5,6. Germline CARD11 mutations have been associated with three types of primary immune disorders, and different types of mutations lead to different phenotypes. Bi-allelic loss-of-function (LOF) mutations are linked to immunodeficiency 11A (IMD11A, OMIM 615206)7, whereas heterozygous gain of function (GOF) and dominant negative (DN) mutations cause B cell expansion with NF-κB and T cell Anergy (BENTA, OMIM 616452) and heterozygous dominant negative mutations causes immunodeficiency 11B with atopic dermatitis (IMD11B, OMIM 617638), respectively8,9. In addition, somatic mutations in CARD11 have been commonly found in some hematologic cancers, especially in diffuse larger B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)11.

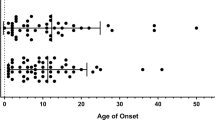

IMD11B is characterized by early onset of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and other allergic conditions in childhood, and patients may have recurrent infections and other immune abnormalities11. Laboratory studies revealed defects in T-cell activation and an elevated IgE levels12. Until now, only 17 different DN mutations from 62 patients have been reported, and most of them are located in the N-terminal CARD and CC domains of the CARD11 protein6,11,13,14,15,16,17.

In this study, we report a Chinese girl with periodic fever and recurrent infections, from whom a new-disease-causing variant (c.2324C > T, p.S775L) in the CARD11 gene (NM_032415) was identified using whole exome sequencing (WES). Further investigation revealed that this mutation led to decreased NF-κB activation and had a DN effect in vitro. In addition, the clinical phenotypes and genotypes of all patients with IMD11B were summarized.

Materials and methods

Genetic tests

Informed consent was procured from the patient's parents, and 2 ml peripheral blood samples were collected from the family members. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Wuhan Children's Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology (NO. 2021R060-E01).

Trio-WES was conducted and the identified variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing using self-designed primers (S775L-F: GCTATGAGCTCTAAGAGCAGC; S775L-R: CAGGTCATGGTCTGTGAAAGG). Conservation analysis of protein amino acid was conducted using MEGA software.

CARD11 plasmid construction and cell transfection

Wildtype CARD11 plasmid (WT-CARD11) was given by Xin Lin (http://n2t.net/addgene:44431) as a gift. S775L-CARD11 and R30W-CARD11 plasmids (a DN mutation, included as a positive control)13, were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. HCT116 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and transfected with 2 μg plasmids (pcDNA3.1, WT-CARD11, R30W-CARD11 and S775L-CARD11) in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Cells were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifugated at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Cell nucleoprotein was extracted using NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 20 μg of total protein was resolved using a 12% SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to PVDF membrane blocked in PBS with 5% milk. The membranes were then probed with the following antibodies: CARD11 (Proteintech, 21741-1-AP), NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, #8242), lamin A/B (Cell Signaling Technology, #12586S) and GAPDH (Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig). After washing, the membrane was incubated HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech) and imaged by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Luciferase reporter assays

After cultured for 12 h in 24-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well), HCT116 cells were co-transfected with 300 ng of pcDNA3.1 + , CARD11-expression vector (WT, R30W and S775L) as needed, 200 ng of pNFκB-luc (Bayotime, Shanghai, China) containing NF-κB binding motifs (GGGAATTTCC), and 100 ng of pRL-TK control plasmid (containing Renillareniformis luciferase gene, Promega, Madison, WI). After 36 h, the cells were lysed and analyzed for luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Three independent experiments were performed to assess luciferase activity.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Empty vectors (pcDNA3.1), Flag-tagged wild type, R30Wand S775L CARD11 variants, along with expression vectors for HA-BCL10 were co-transfected into 293 T cells using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer's protocols. After cells were lysed, anti-HA immunoprecipitation were performed according to the agarose beads instructions (Immunoprecipitation Kit with Protein A + G Agarose Gel). Briefly, the sample and HA-Tag Rabbit antibody were incubated at 4 °C with continuous mixing. Then the antibody-antigen complex was added and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with continuous mixing. After a total of 3 washes with PBS containing 0.1% Tween, samples were resuspended in elution buffer and prepared for electrophoresis.

RNA-seq analysis

The experimental protocol was carried out as described previously18. RNA for RNA-seq was isolated from WT-CARD11 and S775L-CARD11 cells using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One mg of total RNA from each sample was used for cDNA library construction. High-throughput Sequencing was carried out on an Illumina sequencer instrument, and a total of 20 million reads per sample were acquired (2 × 108 bp). The raw data were processed for differential gene expression analysis using transcripts per million (TPM) mapped reads using the TopHat alignment program, and the expression values of reads were normalized using Log2TPM.

Statistical analysis

Graphpad Prism 5 software was used for statistical analyses. Data was subjected to unpaired Student’s t-test to compare two groups or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare one variable among three or more groups. The statistical significance is indicated by a p-value (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). All experiments were performed in duplicates and repeated three times.

Results

Case presentation

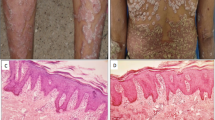

The patient was a 2-year-and-9-month-old girl and referred to the department of rheumatology and immunology with the chief complaints of periodic fever for 2 years and mouth ulcers for 4 months. Since the age of 8 months, the patient had a febrile episode every 2–3 weeks with the maximum temperature being 40.3 °C and 4–5 time of heat peak per day. The episode usually lasted 3–4 days, and the longest one lasted 42 days. The febrile episodes were accompanied by purulent tonsillitis and skin rash. There was no associated cough, sputum, joint pain and swelling, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and ocular signs. The fever was resolved spontaneously or by occasionally oral antipyretics and antibiotics. During the febrile episodes, the increased inflammatory indicators, such as the white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein, and inflammatory factors were increased. At the age of 18 months, she had severe eczema and was treated with hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1% cream, and the symptom was in remission after 2 years of age. She was the only child and her parents were non-consanguineous. Her familial history and birth history were unremarkable.

On physical exam, the child was afebrile, and had normal growth and development. Several painfless lymph nodes (1.2 × 1.0 cm) were palpated in the neck. There were numerous ulcers on the mucous membrane of the mouths, slight bilateral pharyngeal erythema and tonsil enlargment. Laboratory examination showed her white blood cell count (14.28 × 109/L) was increased. The proportion of lymphocytes (32.1%, normal range 23–69%) was normal (Table 1). The CD19 + B cell population was moderately high (1572 cells/mL, normal range 240–1317 cells/mL) and other lymphocytes were within the normal range. Serum IgM level was decreased (0.36 g/L, normal range 0.42–1.73 g/L), and IgG and IgE levels were normal. Inflammatory factors IL8 and TNFα increased significantly. Due to repeated fever and swollen lymph nodes, bone marrow aspiration was performed and no abnormality was observed. Abdominal CT scan was also normal (Fig. 1A). Based on the patient's phenotype, the clinical diagnosis of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome was considered by a rheumatologist.

Characterization of our patient with CARD11 gene mutation. (A) No abnormalities found on bone marrow smear. (B,C) Pedigrees of this family and sanger sequencing of CARD11 mutation. (D) Aligned amino acid sequence at this mutation among different species. The position at residue 775 is noted by a gray bar and highly conserved throughout all indicated species; (E) Scheme of the distribution of the CARD11mutations. Gain of function mutations are highlighted in red, dominant negative mutations are in blue, and loss of function mutations are in black. The mutation found in this study was marked in red box.

Identification of a very rare germline CARD11 mutation

A trio-WES was performed to determine the cause of the patient’s periodic fever and make a further definitive diagnosis. Bioinformatic analysis was conducted to screen possible pathogenic variants from the raw fastq sequencing data. A heterozygous missense mutation (c.2324C > T, p.S775L) was identified in the CARD11 gene (NM_032415), and Sanger sequencing analysis showed it was de novo and not found in her parents (Fig. 1B,C). The mutated site, located between the PDZ and SH3 domains, is conserved among different species (Fig. 1D). The germline variant has been found in the databases (rs2115038523) with no population frequency, while the somatic variant was not listed in the COSMIC database. This variant is interpreted as likely pathogenic according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines for variant classification. Based on the clinical presentations and genetic findings, the genetic diagnosis of IMD11B was made.

Dominant-interfering effect of S775L mutation

As mentioned earlier, IMD11B was caused by heterozygous DN mutations in CARD11, to further clarify the pathogenicity of the S775L variant, an in-vitro functional study was conducted in HCT116 cells. First, we examined the effects of S775L on the expressions of CARD11 gene and protein by transfecting plasmids containing WT-CARD11, S775L, R30W (DN control), and pcDNA3.1( +), respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A–C, S775L did not affect CARD11 mRNA but obviously decreased the expression of CARD11 protein, which indicated that S775L could suppress the expression of CARD11 or impair the stability of CARD11.

Expressions of CARD11-WT and S775L in HCT116 cells. Expressions of RNA and protein of mutant CARD11 and its controls (A,B); (C) Expression levels of mutant CARD11 at different plasmid concentrations. (D) The expression levels of The activity of NF-kB dependent luciferase of cell extracts from each sample with equivalent plasmid was measured and recorded as a fold increase compared to control cells with WT-CARD11 plasmid. (E) The activity of NF-kB dependent luciferase of cell extracts from each sample with equivalent protein was measured. (F) The levels nuclear fraction NF-kB p65 in HCT116 cells transfected with WT or mutant CARD11. GAPDH and Lamin B serve as a control. 2× and 3× indicates the amounts of plasmids used for transfection were double or triple, respectively. NC: normal control, cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 plasmid. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

As CARD11 functions in the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, to further investigate the effects of the S775L mutation, a pNF-κB-luc reporter system was used to evaluate NF-κB activation by transfecting plasmids containing pcDNA3.1(+), WT, S775L, R30W (DN control), and K344del (GOF control)18 to HCT116 cells, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2D, a significantly lower luciferase signaling was observed in cells with mutated S775L compared with that in cells with WT no matter expressing these plasmids alone or coexpressing them with equal WT to mimic heterozygous state of CARD11 mutant (Fig. 2D), suggesting S775L as a DN variant. As S775L was found to suppress the expression of CARD11, to reduce the influence of different protein expression levels on the NF-κB luciferase, we expressed equivalent levels of proteins of WT, S775L and R30W by adjusting the amounts of corresponding plasmid according to the expression level of proteins as shown in Fig. 2B. As expected, the luciferase activity of S775L, was significantly lower compared with WT (Fig. 2E), indicating that S775 has a DN suppression, similar to R30W. Due to both LOF and DN suppression, it is not surprising that the levels of NF-κB p65 in the nuclear fraction were significantly decreased in mutant CARD11 compared to WT CARD11(Fig. 2F).

Additionally, several target genes, such as LAMTOR5, VAV2, BCL2L1, SKP2, IGF1R, RPS6KA1, ATP6V1C1, and FOS in the NF-κB and mTOR signaling pathways had lower expressing levels in HCT116 cells with mutated CARD11 than that in the WT, as detected by RNA-seq (Fig. 3A,B), which further confirms the S775L variant having a LOF suppression.

Transcriptomic analysis in HCT cells transfected with plasmids WT-CARD11 and R30W-CARD11 in transcripts level and in gene level (A,B). Heat map of differentially expressed genes involved in NF-kB and mTOR pathways between WT and S775L by RNA-seq analysis in HCT116 cells. Color scales of heatmap refer to Log2TPM (C).

Immunoprecipitation experiments showed the interaction between CARD11 and BCL10, and mutated CARD11 was found to be involved in the formation of CBM complexes (Fig. 4A). Moreover, Flag-tagged CARD11 variants co-precipitated with wild-type HA-tagged CARD11 when co-expressed in HCT116 cells, showing that mutant CARD11 can directly associate with wild-type CARD11 proteins in CBM complexes (Fig. 4B) and exert dominant negative effect.

Anti-HA immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed in HCT116 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1, WT, R30W, S775L and HA-BCL10.Input lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies to confirm CARD11 expression. CARD11 mutants are still involved in the formation of CBM complexes (A). WT CARD11 can directly associate with mutant CARD11 proteins (B).

Literature review of cases of DN mutations in the CARD11 gene

Literature review of all cases with DN mutations in CARD11 was conducted by using the keywords “CARD11 gene” and “dominant negative mutation” in multiple databases including Pubmed, Medline, and Clinvar. We reviewed 7 articles including 62 cases6,11,13,14,15,16,17 and the clinical information of these patients were summarized in Table 2.

Among the 63 patients (from 26 families), including our patient (Table 2), there were 33 males and 30 females, ranging from 2 months to 77 years of age. The main clinical manifestations of the patients were atopic dermatitis (50/63), recurrent infections (43/63), asthma (33/63), and food allergies (21/63). More than half of the patients had low IgM levels (28/53). The overall clinical phenotypes were heterogeneous, where some patients have severe atopic dermatitis with or without comorbid infections, while others had mild symptoms with asthma or food allergies, and most patients improved over time. Furthermore, a DN mutation (I52T) in CARD11, was identified in a case of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease (VEO-IBD), thus, CARD11 was considered as one of VEO-IBD pathogenic genes, and this findings extends the clinical and immunologic phenotypes related to CARD11 gene deficiency17.

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 17 germline DN mutations have been reported. Fifteen of these mutations lie within the N-terminal CARD or CC domains; and two mutations were in the GUK domain. Seven patients carrying the c.183_196dup variant from two families had severe specific dermatitis, infections, and pneumonia, indicating that this mutation may lead to a more severe phenotype10,14, but this conclusion requires more cases for verification. Other than that, no obvious genotype–phenotype correlation was observed.

Discussion

The possible association of hypomorphic CARD11 activity with atopy was first reported by Goodnow and colleagues in the unmodulated mice being homozygous for a hypomorphic Card11 mutation (p.Leu298Gln)19. This correlation was confirmed by Milner et al. in patients with severe atopic dermatitis carrying heterozygous hypomorphic mutations in CARD1111.

In this work, we reported a 2-year-and 9-month-old patient with periodic fevers, recurrent infections, and eczema. WES revealed a very rare germline mutation c.2324C > T (p.S775L) in the CARD11 gene, which was associated with BENTA, IMD11B, and combined immunodeficiency (CID). Based on the patient’s clinical manifestations, laboratory test results and genetic findings, a genetic diagnosis of IMD11B was considered. Furthermore, we confirmed the DN effect of the S775L mutation through in vitro experiments. The results showed that at the same expression level as wild-type CARD11, S775L led to a downregulation of NF-κB signaling pathway activation, consistent with the previously reported DN R30W. As expected, the expression levels of several genes in the NF-κB and mTOR signaling pathways such as LAMTOR5, VAV2, BCL2L1, SKP2, IGF1R, RPS6KA1, ATP6V1C1, and FOS, were decreased in HCT116 cells with mutated CARD11 than that in the WT, which is consistent with the fact that CARD11 plays an important role in these pathways1,2.

To date, 17 germline DN mutations were identified. Interestingly, most DN mutations (11/17) are located in the CARD domain, a known hot spot for IMD11B; In addition, besides two (R975W and R974C) in the GUK domain, other DN mutations are located within the N-terminal < 200 AA range of the CARD and coiled-coil (CC) domains (which connect to CARD conformationally)20,21. No DN mutations was found between residues 200–970, which includes the C-terminal portion of the CC domain, flexible linker, and PDZ and SH3 domains. S775 is located in the Linker 3 (L3) region (AA753-778) between the PDZ and SH3 domains of CARD11, which is distinct from the locations of previously reported DN mutations, highlighting the uniqueness of the identified DN variant S775L in this study and potentially providing novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of the DN effect.

The CARD and LATCH domains of CARD11 are recognized to participate in the Opening Step of CARD11 signaling. The DN mutations at residues R30, E57, and R72 in the CARD, and H129 in the LATCH, could prevent the inducible association of BCL10 and HOIP with CARD11 downstream of T-cell receprot triggering9,22. As mentioned above, S775 is located in the L3, between the PDZ and SH3 domains of CARD11. L3, SH3, L4, and GUK domains are essential for physiological CARD11 signaling and interact with three of the four small inhibitory elements (RE1-3) in the inhibitory domain of the protein to maintain a spatially close, auto-inhibited conformation; upon CARD11 signaling activation, this conformation changes, separating L3, SH3, L4, and GUK from REs to accommodate the activated receptor20,21. Therefore, we speculate that S775L may lead to abnormally enhanced interactions between L3 and REs, preventing the protein chain from unfolding properly and resulting in downregulation of signaling activation. In order to understand the underlying mechanism, more functional study is needed.

To date, a total of 62 patients with CARD11 DN variants were identified, and their clinical manifestations were highly heterogeneous6,11,13,14,15,16,17. Their main clinical manifestations were atopic dermatitis (79.4%), recurrent infections (68.2%), asthma(52.4%), and food allergies (33.3%). There was no significant genotype–phenotype correlation. Due to the clinical features, including repeated fever at fixed intervals every 2–3 weeks, spontaneous remission resolution (although she was occasionally treated with oral antipyretics and antibiotics), associated tonsillitis, cervical adenitis and skin rash, our patient was considered first as PFAPA at the time of admission. After performing WES and Sanger sequencing, a rare primary immunodeficiency disease, IMD11B, caused by the DN mutation in CARD11, was considered. To our knowledge, this is the first case of a DN mutation in CARD11 to have periodic fever with tonsillitis and skin rash.

The heterogeneity of clinical presentations in patients with CARD DN mutations could be explained by the following reasons. First, the phenomena that atopy was mild or absent in a number of patients may be because these atopic symptoms improved with age6,23,24, which is consistent with the skin features of our patient, who had severe eczema before 18 months of age, but now she has no skin problem. Second, the inhibitory effects of NF-κB activation is different, and some mutants are strong dominant-negative CARD11 variants (R30W, R72Q,) while others are moderate, or weak(N25Y, K83M)9, which may also determine the extent of phenotypic heterogeneity. Last, in addition to atopy, other clinical manifestations, such as infections, mouth ulcers, neutropenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and lymphoma were observed in some patients, which suggests the complexity of pathways CARD11 involved, and more functional studies are needed.

Conclusions

We reported a de novo heterozygous variant in the CARD11 gene from a patient with repeated fever, recurrent infections, and atopic dermatitis. Our functional study provides evidence for the DN effect of this variant and expands the genetic spectrum of this gene. And also, we emphasize the value of WES for genetic diagnosis in rare diseases. Further, functional studies are equally important for a definitive diagnosis.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. RNA-seq data were deposited into the NCBI database under accession number PRJNA998565 and are available at following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA998565. Novel variant was deposited into the Clinvar database with accession number SCV004014849, which was hold until the article published. The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available in Jianguoyun with the identifier URL: https://www.jianguoyun.com/p/DRutwnUQ9pTKCRiY0M0FIAA.

Abbreviations

- DN:

-

Germline dominant negative

- IMD11B:

-

Immunodeficiency 11B with atopic dermatitis

- CARD11:

-

Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 11

- CARMA1:

-

Caspase recruitment domain membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein 1

- MAGUK:

-

Membrane-associated guanylate kinase domain

- IMD11A:

-

Immune disorders, including immunodeficiency 11A

- LOF:

-

Loss of function

- BENTA:

-

B cell expansion with NF-κB and T cell Anergy

- GOF:

-

Gain of function

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse larger B cell lymphoma

- ACMG:

-

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

References

Turvey, S. E. et al. The CARD11-BCL10-MALT1 (CBM) signalosome complex: Stepping into the limelight of human primary immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134(2), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.015 (2014).

Carter, N. M. & Pomerantz, J. L. CARD11 signaling in regulatory T cell development and function. Adv. Biol. Regul. 84, 100890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbior.2022.100890 (2022).

Knies, N. et al. Lymphomagenic CARD11/BCL10/MALT1 signaling drives malignant B-cell proliferation via cooperative NF-κB and JNK activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112(52), E7230–E7238. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1507459112 (2015).

Rawlings, D. J., Sommer, K. & Moreno-Garcia, M. E. Lymphomagenic CARD11/BCL10/MALT1 signaling drives malignant B-cell proliferation via cooperative NF-κB. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6(11), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1944 (2006).

Lenz, G. et al. Oncogenic CARD11 mutations in human diffuse large B celllymphoma. Science. 319(5870), 1676–1679. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153629 (2008).

Dorjbal, B. et al. Hypomorphic caspase activation and recruitment domain 11 (CARD11) mutations associated with diverse immunologic phenotypes with or without atopic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143(4), 1482–1495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.013 (2019).

Greil, J. et al. Whole-exome sequencing links caspase recruitment domain 11 (CARD11) inactivation to severe combined immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131(5), 1376–83.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.012 (2013).

Snow, A. L. et al. Congenital B cell lymphocytosis explained by novel germline CARD11 mutations. J. Exp. Med. 209(12), 2247–2261. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20120831 (2012).

Bedsaul, J. R., Shah, N., Hutcherson, S. M. & Pomerantz, J. L. Mechanistic impact of oligomer poisoning by dominant-negative CARD11 variants. iScience. 25(2), 103810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.103810 (2022).

Davis, R. E. et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 463(7277), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08638 (2010).

Ma, C. A. et al. Germline hypomorphic CARD11 mutations in severe atopic disease. Nat. Genet. 49(8), 1192–1201. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3898 (2017).

Pomerantz, J. L., Milner, J. D. & Snow, A. L. Elevated IgE from attenuated CARD11 signaling: Lessons from atopic mice and humans. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 79, 102255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2022.102255 (2022).

Dadi, H. et al. Combined immunodeficiency and atopy caused by adominant-negative mutation in caspase activation and recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141(5), 1818-1830.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.047 (2018).

Charvet, E. et al. Efficacy of dupilumab for controlling severe atopic dermatitis with dominant-negative CARD11 variant. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 46(7), 1334–1335. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14686 (2021).

Urdinez, L. et al. Expanding spectrum, intrafamilial diversity, and therapeutic challenges from 15 patients with heterozygous CARD11-associated diseases: A single center experience. Front. Immunol. 13, 1020927. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1020927 (2022).

Pietzsch, L. et al. Hyper-IgE and carcinoma in CADINS disease. Front. Immunol. 13, 878989. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.878989 (2022).

Hu, W., Ye, Z., Li, P., Wang, Y. & Huang, Y. Very early onset inflammatory bowel disease caused by a novel dominant-negative mutation of caspase recruitment domain 11 (CARD11). J. Clin. Immunol. 43(3), 528–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-022-01387-2 (2023).

Zhao, P. et al. A novel CARD11 germline mutation in a Chinese patient of B cell expansion with NF-κB and T cell anergy (BENTA) and literature review. Front. Immunol. 13, 943027. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.943027 (2022).

Jun, J. E. et al. Identifying the MAGUK protein Carma-1 as a central regulator of humoral immune responses and atopy by genome-wide mouse mutagenesis. Immunity. 18(6), 751–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00141-9 (2003).

McCully, R. R. & Pomerantz, J. L. The protein kinase C-responsive inhibitory domain of CARD11 functions in NF-kappaB activation to regulate the association of multiple signaling cofactors that differentially depend on Bcl10 and MALT1 for association. Mol. Cell Biol. 28(18), 5668–5686. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00418-08 (2008).

Bedsaul, J. R. et al. Mechanisms of regulated and dysregulated CARD11 signaling in adaptive immunity and disease. Front. Immunol. 9, 2105. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02105 (2018).

David, L. et al. Assembly mechanism of the CARMA1-BCL10-MALT1-TRAF6 signalosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115(7), 1499–1504. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721967115 (2018).

Ominant negative CARD11 mutations: Beyond atopy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143(4), 1345–1347 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.1006.

Lu, H. Y. et al. Germline CBM-opathies: From immunodeficiency to atopy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143(5), 1661–1673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.009 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the patient participating in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants of Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (No. WX19C19); Wuhan City Health and Family Planning Commission of clinical medical research major project (No.WX19M03); Hubei Province Health and Family Planning Commission of Scientific Research Project (No. WJ2019H313). The Construction Project of Clinical Medical Research Center for Neurodevelopment Disorders in Children in Hubei Province (No. HST2020-19) and the Wuhan Children’s Imaging Clinical Medical Research Center (No. WK2022-38).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H., Y.D., and X.L. provided study concepts P.Z., Q.M., and Y.W. designed the study. P.Z., L.Z., Q.M., and X.Z. performed the experiments and the literature research. Y.W., Y.D., and X.L. collected the clinical information. Y.W., X.Z., and L.T. analysed and interpreted data and prepared the figures. X.H., P.Z., and Y.D. prepared the manuscripts. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol was established, according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Wuhan Children's Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from individual or guardian participants.

Consent for publication

All authors approve of the manuscript's submission.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, P., Meng, Q., Wu, Y. et al. A new-disease-causing dominant-negative variant in CARD11 gene in a Chinese case with recurrent fever. Sci Rep 14, 24247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71673-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71673-z