Abstract

As part of obtaining excellent properties that can be used as lead-free hybrid solar cells, the crystal growth, crystal structure, phase transition temperature, and thermal properties for [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 were discussed. The crystal structure at 300 K was determined to be monoclinic by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The phase transition temperatures were determined to be 447 and 473 K, and the results were consistent with the powder XRD patterns. Thermogravimetric analysis revealed thermal stability up to ~ 460 K. The continuous changes in the 1H and 13C chemical shifts and 14N static resonance frequency with increasing temperature are related to variations in the local environment and coordination geometry. The significant differences in activation energies obtained from the 1H and 13C spin–lattice relaxation times (t1ρ) at low and high temperatures were discussed. The activation energy results suggested that the energy barrier at low temperatures was related to the reorientation of the NH3 and CH2 groups around the three-fold symmetry axis, and the energy barrier at high temperatures was related to the reorientation of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3] cation. These physical properties will be provide important insights or potential applications of this crystal.Please check and confirm that the corresponding author and their respective corresponding affiliation have been correctly identified and amend if necessary.OK !

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, studies on improving the efficiency of solar cells based on organic–inorganic halide perovskites CH3NH3PbX3 (X = Cl, Br, and I) have considerably increased; however, these perovskites contain toxic Pb and easily decompose in humid air1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Therefore, upgrading it to a lead-free hybrid type that does not decompose even in humid air is essential. Research on improved functional materials is making significant progress in the development of several organic–inorganic materials. For the development and broad-scale application of lead-free alternatives to solar cells, the strategic use of Ag and Sb for fabricating lead-free bimetallic hybrid materials has recently been reported10. In addition, interest in a new organic–inorganic compound, [NH3(CH2)nNH3]BX4 (B = Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, and Cd, n = 2, 3 …), as an alternative to lead-free and moisture-resistant materials has considerably increased11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. The organic and inorganic components of the crystal structure are related to optical, structural flexibility, thermal, and mechanical properties24,25,26,27,28. The physical and chemical properties of the organic–inorganic compounds depend on the characteristics of the organic cations and the coordination geometry of the inorganic anions; (MX4)2⁻ or (MX6)2⁻29. The organic–inorganic type comprises organic substances and metal-halogen anions, namely [NH3(CH2)nNH3] and BX4, respectively. In [NH3(CH2)nNH3]BX4, the N–H···X hydrogen bonds are connected to NH3 at both ends of the organic chain. When the transition metal M = Mn, Cu, or Cd, the structure consists of alternating corner-shared octahedral (MX6)2⁻ units. The organic and inorganic layers form infinite 2D structures, connected by N − H∙∙∙Cl hydrogen bonds. These two-dimensional hybrid perovskites have diverse applications in electrochemical devices such as chemical sensors, batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells11,18,19,30. In the case of M = Co or Zn, the structure comprises tetrahedral (MX4)2⁻ units positioned between layers of organic cations. The organic and inorganic layers form infinite 1D structures, connected by N − H∙∙∙Cl hydrogen bonds. Moreover, these components of this class attract attention as predominantly luminescent and X-ray luminescent materials31,32,33,34.Please confirm the section headings are correctly identified.OK !

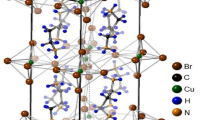

Among these materials, single crystals of [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 (n = 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) with B=Cu and X=Br have monoclinic structures regardless of the length of the alkyl group35,36,37,38. For n = 2, the lattice constants were reported as a = 7.511 Å, b = 7.803 Å, c = 8.334 Å, β = 92.12°, Z = 235. The crystal structure consists of inorganic CuBr4 anions and organic [NH3(CH2)2NH3] cations. The NH3 ions at both ends of the cation and the Br around Cu are made up of hydrogen bonds, forming N–H···Br. The organic chains are located along the crystallographic a-axis.

Further, theoretical analyses of the super-exchange of double halides for [NH3(CH2)3NH3]CuBr4 and [NH3(CH2)4NH3]CuBr4 have been discussed earlier39,40. Additionally, studies on the electronic paramagnetic resonances of these crystals (n=2, 3, and 4) have been reported41. Recently, our group grew single crystals of [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 (n=3, 4, and 6) and reported their single-crystal structures. In addition, we report the structural geometries and energy transfers of the crystals from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) chemical shifts and spin-lattice relaxation time experimental results36,38,42. However, no detailed studies have been reported on the case in which n = 2 is the shortest cation length. Therefore, we studied [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 crystals to understand the effect of cation length.

In this study, the structure and lattice constant of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 (ethanediammonium copper bromide) single crystals were determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD). The phase transition temperature (TC) and thermodynamic properties are discussed, and the structural geometries of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3] cations are determined from NMR chemical shifts. In addition, the energy transfer was considered by the NMR spin-lattice relaxation time (t1ρ), and the changes in the activation energy (Ea) in accordance with the structural geometry are discussed. We compared the structure, thermal properties, and spin-lattice relaxation times with various n in previously reported [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 (n = 3, 4, and 6) with those of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 examined in this study36,38,42. These results are prospective to provide valuable information for the development of orgain-inorganic material based solar cells.

Methods

Crystal growth

Single crystals of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 were prepared using molecular weights of NH2(CH2)2NH2·2HBr (Aldrich, 98%) and CuBr2 (Aldrich, 99.9%) at a ratio of 1:1 in aqueous solution. The mixture was stirred and heated to obtain a saturated solution. The resulting solution was filtered and single brown crystals were grown by slow evaporation for a few weeks in a thermostat at 300 K. The crystals grew into rectangular shapes with dimensions of 3 × 3 × 1 mm3.

Characterization

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves were obtained using a DSC instrument (25, TA Instruments) at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in the 200–570 K range under a dry nitrogen gas flow. The crystal morphology and melting phenomena with respect to the temperature change were observed using an optical polarizing microscope (Carl Zeiss) on a hot stage (Linkam THMS 600). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve was also obtained at 10 °C/min heating rate, in the temperature range of 300–873 K under nitrogen gas flow.

The structure and lattice parameters at 300 K were determined using SCXRD experiments at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI) of the Seoul Western Centre. The crystal was mounted on a diffractometer (Bruker D8 Venture PHOTON III M14) with a graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα target and a nitrogen cold stream (−50 °C). Data were collected using the SMART APEX3 and SAINT programs and corrected for absorption using the multi-scan method obtained from SADABS. The single-crystal structure was analyzed using direct methods and supplemented with the squares of the least squares of the entire matrix of F2 using SHELXTL43. All nonhydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined, and hydrogen atoms were included at geometrically ideal positions. Further, the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded at various temperatures using an XRD spectrometer with a Mo-Kα radiation source utilizing the SCXRD method. The experimental conditions were similar to those reported previously29.

The NMR spectra of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 crystals were recorded using a solid-state NMR spectrometer (Bruker 400 MHz Avance II+) at KBSI. The 1H magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR at the Larmor frequency of ωo/2π = 400.13 MHz and the 13C MAS NMR experiment at the Larmor frequency of ωo/2π = 100.61 MHz were measured as a function of temperature. To minimize the spinning sideband, the MAS speed was measured at 10 kHz. 1H and 13C chemical shifts were recorded using tetramethylsilane as the standard. The 1D NMR spectra of 1H and 13C were obtained with a delay time of 0.5 s. 1H and 13C spin-lattice relaxation time (t1ρ) values were measured with a delay time from 200 μs to 100 ms; a 90° pulse was used for 1H and 13C at 3.6–3.8 μs. The 13C t1ρ values were obtained by varying the 13C spin-locking pulse applied after cross-polarization (CP) preparation. In addition, the static 14N NMR resonance frequency at a Larmor frequency of 28.90 MHz was obtained with increasing temperature. The 14N NMR resonance frequency was obtained using NH4NO3 as the reference standard, and 14N NMR spectra were measured using a solid-state echo sequence. The NMR chemical shifts and t1ρ values were measured over a temperature of 180–430 K. The temperature was maintained within an error range of ± 0.5 K by adjusting the nitrogen gas flow and heater current.

Experimental results

Single-crystal XRD results

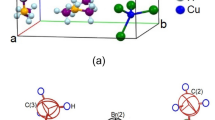

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 crystal at 300 K revealed that the crystal structure was monoclinic with space group P21/c. The lattice parameters are a = 8.3365 (2) Å, b = 7.8056 (2) Å, c = 7.5156 (2) Å, β = 92.062 (1)°, and Z = 2. The detailed SCXRD results are listed in Table 1, and the single-crystal structure is shown in Fig. 1a. This single crystal is composed of [NH3(CH2)2NH3] cations and CuBr6 anions, and the Cu atoms in CuBr6 are surrounded by six Br atoms (Fig. 1b). NH3 groups are located between the CuBr6 octahedra at both ends of the cation. The hydrogen bonding of N–H···Br was connected between the Cu–Br layer and the alkylammonium chain. The bond lengths for three types of N–H···Br are 2.500, 2.676, and 2.530 Å, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1b. The Cu–Br, N–C, and C–C bond lengths are listed in Table 2. The CIF file results obtained from the SCXRD experiment for the crystal structure at 300 K are deposited in the Cambridge Data Base (CCDC 2323282).

Phase transition temperature

DSC experiments on [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 crystals were performed at a heating rate of 10 °C/min with a sample amount of 4.5 mg. The two endothermic peaks at 447 and 473 K shown in Fig. 2 are substantially strong, and the corresponding enthalpies for the peaks are 3.67 and 3.66 kJ/mol, respectively. A weak endothermic peak was observed at 487 K with a smaller enthalpy of 1.63 kJ/mol.

To confirm whether the peaks at high temperatures in the DSC curve of Fig. 2 are phase transition temperatures, optical polarizing microscopy was performed according to the temperature change, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2. When the temperature was increased from 300 to 473 K (including 447 and 473 K), the morphology of the single crystals did not change. When the temperature reached 497 K, a significant amount of single crystals melted, and when 603 K was reached, most single crystals appeared to melt.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern

PXRD experiment was performed for each temperature change in the 2θ range of 8°–60° (Fig. 3). The PXRD patterns recorded below 400 K (gray) differ slightly from those recorded at 450 K (red); this difference is related to the phase transition temperature TC1 (=447 K). The PXRD pattern recorded at 450 K differed from that obtained at 480 K (blue), indicating a clear phase transition temperature, TC2 (=473 K). The pattern at 500 K is completely different from that at 480 K, and no crystallinity is observed, suggesting that it is the melting temperature. This result correlates well with the three endothermic peaks obtained from the DSC results. The simulated XRD pattern based on the CIF file at 300 K is shown in Fig. 3, and agrees well with the PXRD experimental pattern at 300 K. The PXRD peaks observed in this diffractogram are obtained using a Mercury program. Therefore, the DSC, PXRD, and optical polarizing microscopy results indicate that the phase transition temperatures are TC1 = 447 K, and TC2 = 473 K, whereas the melting temperature is Tm = 487 K.

Thermodynamic property

The TGA experiments were performed at temperatures ranging from 300 to 900 K with a sample amount of 9.39 mg. The thermograms are shown in Fig. 4. The TGA results reveal that this crystal is thermally stable up to 460 K. The initial weight loss of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 begins at 460 K, representing a partial decomposition temperature with a weight loss of 2%. The endothermic peak at 489 K in the DTA curve is consistent with the peak at 487 K in the DSC curve. The crystal exhibited melting almost at this temperature, as observed by optical polarizing microscopy. In the TGA curve, [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 exhibits a two-stage decomposition phenomenon at high temperatures. An initial weight loss of 18% occurred in the range of 500–600 K, which was due to the decomposition of HBr. A second-stage decomposition of 36% occurred at 600–650 K. The weight losses of 18% and 36% at approximately 540 and 610 K, respectively, are likely due to the decomposition of the HBr and 2HBr moieties. The amount remaining as a solid was calculated from the TGA results and the molecular weight, and weight loss of 55% were predominantly attributed to organic decomposition.

1H and 13C MAS NMR chemical shifts

Two 1H NMR signals of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 were expected due to NH3 and CH2, but only one signal was recorded in the NMR spectroscopic analysis. The 1H NMR signal at 300 K is shown inset of Fig. 5. The spinning sidebands of the protons are represented by asterisks. The signal with a wide linewidth resulted from the overlap of protons in NH3 and CH2, and the linewidth is temperature-independent at approximately 6.38 ppm. At 300 K, the 1H NMR chemical shift is observed at approximately δ = 10.74 ppm.

In addition, 1H NMR chemical shift moved continuously downfield without any anomalous changes as the temperature increased.

The temperature dependence of 13C NMR chemical shifts of [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 is shown in Fig. 6. The 13C MAS NMR spectrum at 300 K exhibited one resonance signal, and the 13C chemical shift was recorded at 107.42 ppm. 13C NMR chemical shifts shifted without an anomalous change from 135 to 90 ppm with an increase in temperature. The linewidth also tended to decrease as the temperature increased, similar to 13C chemical shift changes.

The NMR chemical shifts due to the local field around the 1H and 13C nuclei indicate changes in the crystallographic geometry. The chemical shift of 1H shifted downfield within a small range, while the chemical shift of 13C shifted downfield with a wider range than that of 1H. This implies that the source of the interaction between the atoms and ions around the 1H and 13C nuclei is the same. And the decrease in line width for 13C implies that the molecular motion of 13C becomes active as the temperature increases.

14N static NMR resonance frequency

The in situ 14N static NMR spectrum of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 single crystal was obtained for temperature changes in the range of 180–420 K using the solid-state echo method. The range of 14N resonance frequency exhibited a significantly wider span than that of 1H chemical shift, suggesting that it is valuable for considering the surrounding environment of 14N. An external magnetic field was applied to the single crystal in an arbitrary direction. The NMR spectrum, as the spin number of 14N is I = 1, predicts two resonance lines owing to the quadrupole interaction43. However, owing to the low Larmor frequency of 28.90 MHz required to obtain the 14N NMR spectrum, the intensity of the 14N signals is extremely low, consequently measuring it is difficult, (Fig. 7a). Despite the wiggling of the baseline is severe, low-intensity signals are visible, and these peaks are marked using circles. 14N NMR signals appearing on the left and right sides of the zero point of the resonance frequency are shown according to the temperature changes. The 14N resonance frequency, as shown in Fig. 7b, decreased as the temperature increased, showed only one signal at approximately 360 K, and then increased again. In other words, the symmetry of the structural geometry at approximately 14N improves at approximately 360 K. The continuous change in the 14N resonance frequency with increasing temperature indicated a variation in the coordination geometry and local environment of the 14N atoms.

1H and 13C NMR spin-lattice relaxation times

The intensity changes by changing the delay times for the 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at a given temperature, and the relationship of the decay rate of the magnetization was defined by the spin-lattice relaxation time, t1ρ:44,45,46

where W(τ) and W(0) are the signal intensities at time τ, and τ=0, respectively. 1H t1ρ values for [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 are obtained from the slope of the intensities vs. delay times as shown in Fig. 8 as a function of inverse temperature using Eq. (1). The 1H t1ρ values are of the order of a few ms, and the values marginally decrease with increasing temperature, and the t1ρ values exceeding 380 K rapidly decreased.

The intensity changes in the 13C NMR spectra were also assessed by increasing the delay time at a given temperature in the same approach as the 1H t1ρ measurement method. The 13C t1ρ values from the slope of their recovery traces can be obtained using Eq. (1); the t1ρ values for 13C are shown in Fig. 8. The 13C t1ρ value at 300 K is 68.58 ms, and the 13C t1ρ values are approximately 10 times higher than the 1H t1ρ values. The t1ρ values marginally decreased as the temperature increased, whereas the t1ρ values above 320 K abruptly decrease.

The experimental values of t1ρ can be expressed by the correlation time τC for reorientational motion, and the t1ρ value for molecular motion is given using Eq. (2):46,47

where R is a constant, ω1 is the spin-lock field, and ωC and ωH are the Larmor frequencies for 13C and 1H, respectively. Local field fluctuations are caused by thermal motion, which is activated by thermal energy.

The 1H and 13C t1ρ values exhibited similar variations due to similar molecular motions of the C–H bond. The 1H and 13C t1ρ values were attributed to the slow motions at all temperatures, and the slow motion is represented as ω1τC >> 1. Typically, the spin-lattice relaxation time is given as t1ρ−1 α exp(−Ea/kBT) from Eq. (2)47. τC or t1ρ is generally expressed as an Arrhenius-type equation based on the activation energy Ea for molecular motion and temperature. The magnitude of Ea depends on the molecular dynamics. The Ea for 1H obtained from the slope of t1ρ vs. 1000/temperature plot represented by red squares in Fig. 8 at low and high temperatures are 0.54 ± 0.08, and 5.57 ± 0.99 kJ/mol, respectively. In addition, the activation energy, Ea for 13C obtained from the slope of t1ρ vs. 1000/temperature represented by blue squares in Fig. 8 at low and high temperatures are 0.28 ± 0.14, and 27.53 ± 2.16 kJ/mol, respectively.

Conclusion

The structure of the lead-free organic–inorganic [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4 crystal was monoclinic at 300 K, and the determined phase transition temperatures were 447 and 474 K. These results were consistent with the powder XRD patterns. The continuous changes in the 1H and 13C chemical shifts and 14N static resonance frequency with increasing temperature were affected by variations in the coordination geometry and local environment. In addition, the fact that 1H t1ρ is shorter than 13C t1ρ indicates that the energy transfer of 1H is very easy. In addition, the activation energies of 1H and 13C show a significant difference. Activation barriers for the molecular reorientation of the cation in the low and high temperatures were determined based on temperature measurements of the relaxation time in the t1ρ rotational system for 1H and 13C. The activation barrier at low temperatures is approximately 10~100 times lower than that at high temperatures. The Ea results showed that at low temperatures, the energy barrier was associated with the reorientation of the NH3 and methylene groups around the three-fold symmetry axis, and at high temperatures, it was associated with the reorientation of the [NH3(CH2)2NH3] cation.

We compared the structure, space group, lattice constants, thermal properties, and spin-lattice relaxation times as a function of the length n of the CH2 groups in [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 (n = 2, 3, 4, and 6). Even though the methylene lengths of the cation were different, they all had the same monoclinic structure at room temperature as shown in Table 3. However, as the length of n increases, the length of lattice constants a remains almost constant, but the lengths of b and c become longer. Td shows a tendency to gradually decrease depending on the length, except for n = 2. In addition, the T1ρ of 1H had almost similar values of 1 to 9 ms, and the 13C T1ρ had a value of 2 to 70 ms. These values show short T1ρ values when paramagnetic ions are included. These detailed physical properties of the crystal will be immensely advantageous for its potential applications as eco-friendly materials.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available in the CCDC 2323282.

References

Zhang, M. et al. Selective valorization of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran using atmospheric O2 and MAPbBr3 perovskite under visible light. ACS Catal. 10, 14793 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. In situ synthesis of lead-free halide perovskite–COF nanocomposites as photocatalysts for photoinduced polymerization in both organic and aqueous phases. ACS Mater. 4, 464 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. Under the spotlight: The organic–inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic applications. Nano Today 10, 355 (2015).

Hermes, M. et al. Ferroelastic fingerprints in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. J. Phys. Chem. 120, 5724 (2016).

Strelcov, E. et al. CH3NH3PbI3 perovskites: Ferroelasticity revealed. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602165 (2017).

Abdel-Aal, S. K., Abdel-Rahman, A. S., Kocher Oberlehner, G. G., Ionov, A. & Mozhchil, R. Structure, optical studies of 2D hybrid perovskite for photovoltaic applications. Acta Crystallogr. A 70, C1116 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Chemical nature of ferroelastic twin domains in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite. Nat. Mater. 17, 1013 (2018).

Mauck, C. M. et al. Inorganic cage motion dominates excited-state dynamics in 2D-layered perovskites (CxH2x+1NH3)2PbI4 (x = 4–9). J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 27904 (2019).

Dahlman, C. J. et al. Dynamic motion of organic spacer cations in ruddlesden-popper lead iodide perovskites probed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Matter 33, 642 (2021).

Wang, C.-F. et al. Discovery of a 2D hybrid silver/antimony-based iodide double perovskite photoferroelectric with photostrictive effect and efficient X-ray response. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205918 (2022).

Rao, C. N. R., Cheetham, A. K. & Thirumurugan, A. Hybrid inorganic–organic materials: A new family in condensed matter physics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 83202 (2008).

Cheng, Z. & Lin, J. Layered organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites: structure, optical properties, film preparation, patterning and templating engineering. Cryst. Eng. Com. 12, 2646 (2010).

Mostafa, M. F. & El-khiyami, S. S. Crystal structure and electric properties of the organic–inorganic hybrid: [(CH2)6(NH3)2]ZnCl4. J. Solid State Chem. 209, 82 (2014).

Gonzalez-Carrero, S., Galian, R. E. & Perez-Prieto, J. Organometal halide perovskites: Bulk low-dimension materials and nanoparticles. Part. Syst. Charact. 32, 709 (2015).

Abdel-Adal, S. K., Kocher-Oberlehner, G., Ionov, A. & Mozhchil, R. N. Effect of organic chain length on structure, electronic composition, lattice potential energy, and optical properties of 2D hybrid perovskites [(NH3)(CH2)n(NH3)]CuCl4, n = 2–9. Appl. Phys. A 123, 531 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. Giant two-photon absorption and its saturation in 2D organic-inorganic perovskite. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1601045 (2017).

Mondal, P., Abdel-Aal, S. K., Das, D. & Manirul Islam, S. K. Catalytic activity of crystallographically characterized organic-inorganic hybrid containing 1,5-Di-amino-pentane tetrachloro manganate with perovskite type structure. Cat. Let. 147, 2332 (2017).

Elseman, M. et al. Copper-substituted lead perovskite materials constructed with different halides for working (CH3NH3)2CuX4-based perovskite solar cells from experimental and theoretical view. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 11699 (2018).

Aramburu, J. A., Garcia-Fernandez, P., Mathiesen, N. R., Garcia-Lastra, J. M. & Moreno, M. Changing the usual interpretation of the structure and ground state of Cu2+-layered perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 5071 (2018).

Staskiewicz, B., Czupinski, O. & Czapla, Z. On some spectroscopic properties of a layered 1,3-diammoniumpropylene tetrabromocadmate hybrid crystal. J. Mol. Struct. 1074, 723 (2014).

Staskiewicz, B., Turowska-Tyrk, I., Baran, J., Gorecki, C. & Czapla, Z. Structural characterization, thermal, vibrational properties and molecular motions in perovskite-type diaminopropanetetrachlorocadmate NH3(CH2)3NH3CdCl4 crystal. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 75, 1305 (2014).

Czapla, Z. et al. Structural phase transition in a perovskite-type NH3(CH2)3NH3CuCl4 crystal–X-ray and optical studies. Phase Transit. 90, 637 (2017).

Waskowska, A. Crystal structure of dimethylammonium tetrabromocadmate (II). Zeit. Kristallogr. 209, 752 (1994).

Xie, Y. et al. The soft molecular polycrystalline ferroelectric realized by the fluorination effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12486 (2020).

Fu, D.-W. et al. High-Tc enantiomeric ferroelectrics based on homochiral dabcoderivatives (Dabco = 1,4-Diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17477 (2020).

Zhang, W. & Xiong, R.-G. Ferroelectric metal–organic frameworks. Ferroelectric metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 1163 (2012).

Lim, A. R. & Joo, Y. L. Study on structural geometry and dynamic property of [NH3(CH2)5NH3]CdCl4 crystal at phases I, II, and III. Sci. Rep. 12, 4251 (2022).

Lim, A. R. Effect of methylene chain length of perovskite-type layered [NH3(CH2)nNH3]ZnCl4 (n=2, 3, and 4) crystals on thermodynamic properties, structural geometry, and molecular dynamics. RSC Adv. 11, 37824 (2021).

Czupinski, O., Ingram, A., Kostrzewa, M., Przeslawski, J. & Czapla, Z. On the structural phase transition in a perovskite-type diaminopropanetetrachlorocuprate(II) NH3(CH2)3NH3CuCl4 crystal. Acta Phys. Pol. A 131, 304 (2017).

Rong, S.-S., Faheem, M. B. & Li, Y.-B. Perovskite single crystals: Synthesis, properties, and applications. J. Electron. Sci. Tech. 19, 100081 (2021).

Kundu, J. & Das, K. Low dimensional, broadband, luminescent organic-inorganic hybrid materials for lighting applications. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 44, 4508 (2021).

Zhai, Y., Xie, H., Cai, P. & Seo, H. J. A luminescent inorganic-organic hybrid materials containing the europium(III) complex with high thermal stability. J. Luminescence 157, 201 (2015).

Meng, H. et al. High-efficiency luminescent organic-inorganic hybrid manganese(II) halides applied to X-ray imaging. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 12286 (2022).

Rhaiem, T. B., Elleuch, S., Boughzala, H. & Abid, Y. A new luminescent organic-inorganic hybrid material based on cadmium iodide. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 109, 107572 (2019).

Halvorson, K. & Willett, R. D. Structures of ethylenediammonium tetrabromocuprate(II) and propylenediammonium tetrabromocuprate(II). Acta Cryst. C44, 2071 (1988).

Lim, A. R. Dynamic motions of organic cation in organic–inorganic hybrid 1,4-butanediammonium tetrabromocuprate (II) crystal by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 1252, 132204 (2022).

Garland, J. K., Emerson, K. & Pressprich, M. R. Structures of four- and five-carbon alkyldiammonium tetrachlorocuprate(II) and tetrabromocuprate(II) salts. Acta Cryst. C46, 1603 (1990).

Lim, A. R. & Kwac, L. K. Advances in physicochemical characterization of lead-free hybrid perovskite [NH3(CH2)3NH3]CuBr4 crystals. Sci. Rep. 12, 8769 (2022).

Snively, L. O., Haines, D. N., Emerson, K. & Drumheller, J. E. Two-halide superexchange in [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 for n=3 and 4. Phys. Rev. B 26, 5245 (1982).

Straatman, P., Block, R. & Jansen, L. Theoretical analysis of double-halide superexchange in layered solids of the compounds [NH3(CH2)nNH3]CuBr4 with n=3 and 4. Phys. Rev. B 29, 1415 (1984).

Kite, T. M. & Drumheller, J. E. Electron paramagnetic resonance of the eclipsed layered compounds NH3(CH2)nNH3CuBr4 with n = 2, 3, 4. J. Mag. Reson. 54, 253 (1983).

Lim, A. R. Structural geometry and molecular dynamics by nuclear magnetic resonance of organic-inorganic perovskite [NH3(CH2)6NH3]CuBr4 crystal near phase transition temperature. Solid State Commun. 378, 115418 (2024).

SHELXTL v6.10 (Bruker AXS, Inc., 2000).

Abragam, A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism (Oxford University Press, 1961).

Koenig, J. L. Spectroscopy of Polymers (Elsevier, 1999).

Harris, R. K. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (Pitman Pub, 1983).

Lim, A. R. Investigation of the structure, phase transitions, molecular dynamics, and ferroelasticity of organic–inorganic hybrid NH(CH3)3CdCl3 crystals. RSC Adv. 13, 18538 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant, funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C2006333). The work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2016R1A6A1A03012069).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.L. designed the project, X-ray, NMR experiment, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, A.R. Single-crystal growth, crystal structure, and molecular dynamics of organic–inorganic [NH3(CH2)2NH3]CuBr4. Sci Rep 14, 20532 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71702-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71702-x