Abstract

To study the resistance of rice husk ash-rubber-fiber reinforced concrete (RRFC) to dry–wet cycle/chloride erosion under a hygrothermal environment, the optimal combination was selected by an orthogonal test. The peak strain, residual strain, and fatigue damage strength of the optimal group of RRFC samples under cyclic loading and unloading after dry–wet cycle/chloride erosion under different environments and temperatures were compared and analyzed. After that, microscopic analysis and anti-erosion mechanism analysis were carried out. The results show that the axial peak and residual strain of RRFC specimens increase continuously during the repeated loading–unloading process, and the increase of axial peak and residual strain in the first five cycles is the most obvious. Among them, RRFC has the most significant increase in axial peak strain after 14 dry–wet cycles, which is 11.73%. The rice husk ash reacted with Ca(OH)2 in the specimen to precipitate C—S—H gel, which improved the specimen’s corrosion resistance and fatigue resistance. The rubber in the specimen has high elasticity, which reduces the fatigue damage of the specimen during cyclic loading and unloading, thus showing higher fatigue failure strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global warming and environmental pollution are becoming increasingly severe, with cement being one of the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. As population growth and urbanization accelerate, the issue of natural resource depletion has become more pronounced1,2,3. The Chinese government has proposed energy conservation and emission reduction goals, and various industries are responding to this call4,5. Rice husk, a type of biomass, plays a significant role in biomass energy development due to its high yield6,7,8. Most rice husks are utilized as fuel for power generation, but if the byproduct—rice husk ash—is not effectively used, it can lead to environmental pollution and resource wastage9. Therefore, finding ways to utilize rice husk ash has become an urgent concern in China’s biomass energy sector. Research teams have explored the potential of using rice husk ash in concrete production, where it has been shown to improve mechanical properties10,11,12. For instance, A.L.G. Gastaldini et al.13 found that as the amount of rice husk ash increases, the total shrinkage and compressive strength of concrete improve, but the chloride ion permeability after shrinkage also increases. When the replacement rate of rice husk ash is 5%, the cost-effectiveness of concrete is highest. Research by Zhi-hai He et al.14 indicated that adding rice husk ash to concrete can enhance its compressive strength and elastic modulus while reducing creep. Cheolwoo Park et al.15 discovered that incorporating acid-leached rice husk ash significantly improves the frost resistance of concrete, mainly due to the unique microstructural characteristics of the rice husk ash.

Crumb rubber concrete (CRC), as a new type of concrete material, is made by replacing fine aggregates with rubber particles. The accumulation of a large number of waste tires has caused “black pollution,” with only a small portion being recycled16,17,18. Rubber contains toxic vulcanization products, and long-term accumulation leads to environmental pollution19,20. Although adding rubber particles to concrete reduces its strength, it enhances the mechanical properties such as toughness, frost resistance, and fatigue resistance21,22,23. For example, research by Zhang Baifa et al.24 showed that when the rubber particle addition ratio is 10%, the strength and frost resistance of the concrete are optimal. Chiraz Kechkar et al.25 indicated that adding rubber particles can reduce the strength of concrete but improves its resistance to H2SO4, Na2SO4, and seawater corrosion, reduces shrinkage and microcracks, and enhances durability. Najib N. Gerges et al.26 found that concrete incorporating recycled rubber powder exhibits high rebound, low density, high toughness, and good impact resistance.

The addition of rubber particles inevitably weakens the static mechanical properties of concrete27,28. To address this, many experts have attempted to add fibers to enhance its mechanical properties29,30,31. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers are widely used in concrete construction due to their excellent crack resistance and chemical compatibility32,33,34. This study found that adding PVA fibers to rubber concrete effectively improved its elastic modulus and ductility, alleviating the adverse effects of rubber particles on the mechanical properties of concrete. Simultaneously, incorporating rubber particles, rice husk ash, and PVA fibers into concrete can achieve complementary and synergistic toughening mechanisms among the components, significantly enhancing the overall toughness and durability of the concrete. This multi-component composite material design not only improves the mechanical properties of concrete but also enhances its crack resistance and durability, thereby meeting the higher requirements of engineering applications.

Chloride salt corrosion is a primary factor in the durability degradation of concrete structures in service35,36. In tropical coastal areas, concrete road tunnels, for example, are not only subjected to long-term chloride salt corrosion but also affected by humid environments37 and cyclic loading38, resulting in serious damage to the mechanical properties of concrete39,40. To mitigate such damage, this paper incorporates waste materials and fibers into concrete to create a new type of green concrete41,42, providing new materials for the construction of tropical concrete road tunnels while also holding significant energy-saving and environmental protection implications.

Test

Raw materials

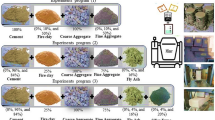

The test cement used in this study is P·O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement, produced by the Bagongshan Cement Plant in Huainan, China. Its chemical composition is detailed in (Table 1). Rice husk ash, sourced from the Hubei Huadian Xiangyang Power Generation Co., Ltd., is utilized in this research, and its chemical composition is presented in (Table 2). For the cube specimens, the coarse aggregate consists of crushed stone and pebbles with sizes ranging from 5 to 15 mm, while the cylindrical specimens utilize coarse aggregate ranging from 5 to 10 mm. The apparent density of the aggregates is 2750 kg/m3. Medium sand from the Huaihe River in China is selected as the fine aggregate, with a fineness modulus of 2.6. The rubber particles employed in the tests are derived from waste rubber tires, with average particle sizes of 0.4–0.6 mm, 1–2 mm, and 2–4 mm, as illustrated in (Fig. 1). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber, sourced from Shanghai Yingjia Industrial Development Co., Ltd., has a length of 12 mm, with its physical and microscopic characteristics shown in (Fig. 2). Additionally, the high-performance water-reducing agent HPWR, produced by Qinfen Building Materials Factory in Shanxi Province, China, was selected for this study.

Concrete mix design

According to the specification, the mix ratio of C30 ordinary concrete was designed. The test set three factors: rubber particle size (factor A), PVA fiber (factor B), and rice husk ash content (factor C), and each factor set three levels. Three factors and three levels of orthogonal test were carried out. The L9 (33) orthogonal test table was finally selected according to the factor level in the orthogonal test. A new type of rubber concrete was prepared by mixing rubber, PVA fiber, and rice husk ash into concrete. The mix ratio is shown in (Table 3) Ref.43,44,45,46.

According to the standard of concrete mechanical properties test method, the compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength of concrete with standard curing for 28 days were tested. The results are shown in (Table 4) Ref.47,48. The fifth group was selected as the best ratio in this experiment through visual analysis, range analysis, variance analysis, and efficacy coefficient analysis. The results of the efficacy coefficient method are shown in (Table 5). In order to analyze the influence of the shape of the specimen on the results, the experiment was repeated on the cylinder sample to measure its performance index, and the verification results were consistent with the cube test results. The optimal ratio was A2B2C3; that is, the particle size of rubber particles was 1–2 mm, the content of PVA fiber was 1.2 kg m3, and the content of rice husk ash was 15%.

Test scheme design

Based on the optimal mix ratio obtained from the orthogonal test, cylindrical test blocks of rice husk ash-rubber-fiber concrete (RRFC) were prepared with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm. The specimens were categorized into six groups and subjected to a constant temperature water bath at 20, 60, and 80 °C. Each temperature gradient was tested in two solutions: clear water and a 5% NaCl solution. To thoroughly investigate the effects of the hygrothermal environment on the fatigue performance of the RRFC specimens, dry–wet cycle tests were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. The testing procedure involved soaking the specimens in a constant temperature water tank for 16 h, followed by drying in an oven for 6 h and cooling for 2 h. The dry–wet cycles were applied for 0, 7, 14, 28, and 56 cycles, respectively. The methodology for the dry–wet cycle test is illustrated in (Fig. 3).

The uniaxial compressive failure load of the cylinder is measured. In the cyclic loading and unloading test, 500 N force is pre-loaded to the test block before the test to ensure the correct alignment and full contact between the test block and the test device. The test process adopts stress control, the loading and unloading rate is 30KN/min, and the loading frequency is 5Hz. The upper limit of the loading load is 60% of the uniaxial compressive failure load, and the lower limit of the unloading load is 100 N. A loading and unloading process is used as a cycle, and a total of 50 cycles are performed for cyclic loading and unloading tests.

Test results and analysis

When the RRFC test block reaches the corresponding dry–wet cycle times (0 time, 7 times, 14 times, 28 times and 56 times) in different hot and humid environments, the uniaxial compression test and cyclic loading and unloading test are carried out to analyze the fatigue damage law.

Figure 4 depicts the stress–strain curve of a single cycle for an RRFC specimen. Under cyclic loading, the specimen undergoes three main stages:

-

1. Compaction stage: The curve shows a concave shape, with stress remaining at a low level and increasing slowly as strain gradually rises. This is due to the initial irregularity of the specimen surface, which becomes gradually compacted and smoother during the initial loading phase, closing internal pores formed during specimen infusion and rubber hydrophobicity.

-

2. Approximate linear elastic stage: In this stage, the stress–strain curve mainly shows linear growth, with stress increasing rapidly and stably as strain increases. This is because the internal pores of the specimen are gradually compacted and tend to be in a dense state, and the specimen is uniformly compressed, so the overall structure appears stable.

-

3. Crack development stage: In this stage, the curve shows a convex shape, with stress increasing at a slower rate as strain increases. This is due to the increasing loading stress, which gradually causes internal pores of the specimen to rupture, resulting in pore penetration and microcrack formation, weakening specimen brittleness, and increasing ductility.

Peak strain and residual strain analysis

The test was conducted following a cyclic loading–unloading protocol. The strain recorded at the maximum axial stress during loading is termed the axial peak strain, while the strain value upon unloading to 100 N is referred to as the axial residual strain. Figure 5 and Fig. 6 Figures 5, 6 illustrate the variations in axial peak strain and axial residual strain of the RRFC specimens as the number of cyclic loading–unloading cycles increases, following different dry–wet cycles in a chloride environment at 80 °C.

The axial peak strain represents the maximum strain experienced by the concrete specimen in a single cycle, serving as a key parameter for assessing the specimen's capacity to endure maximum deformation. Conversely, the axial residual strain reflects the irreversible deformation that results from a single stress cycle, indicating the degree to which the concrete cannot recover. Given that concrete exhibits both brittleness and ductility, structural damage is primarily attributed to deformation. Strain is a crucial parameter for monitoring material deformation and is a fundamental index for evaluating the safety performance of concrete materials.

From Fig. 5, it is evident that despite variations in the number of dry–wet cycles, the trend of axial peak strain in RRFC specimens as loading–unloading cycles increase remains consistent. The axial peak strain increases continuously during the repeated loading–unloading process. The increase of axial peak strain is the most obvious in the first five cycles, and then gradually slows down and tends to be stable, reflecting the trend of the hysteresis curve from sparse to dense. After 0, 7, 14, 28 and 56 dry–wet cycles of RRFC specimens, the axial peak strain of the 50th loading–unloading cycle increased by 11.29, 6.48, 11.73, 10.77 and 8.39% respectively compared with the axial peak strain of the first loading–unloading cycle.At the same time, the axial peak strain of the specimen with 7 times of dry–wet cycle is the smallest, and the axial peak strain of the specimen with 56 times of dry–wet cycle is the largest. Under the same loading–unloading cycles, the axial peak strain of RRFC specimens decreases first and then increases with the number of dry–wet cycles. This indicates that the longer the dry–wet cycle/chloride erosion time, the greater the axial peak strain of the RRFC specimen.

Figure 6 shows that the axial residual strain also increases progressively during the cyclic loading–unloading process across each dry–wet cycle stage. The most substantial increase occurs in the first five loadings, after which the overall growth rate gradually stabilizes. The axial residual strains of RRFC specimens at the end of the first loading–unloading cycle were 1.79 × 10−3, 1.49 × 10−3, 1.81 × 10−3, 2.49 × 10−3 and 2.98 × 10−3 respectively after 0, 7, 14, 28 and 56 times of dry–wet cycles. This is because the more the dry–wet cycles, the more the internal pores of the specimen, the greater the axial residual strain. At the same time, on the whole, the axial residual strain of the specimen with 7 times of dry–wet cycle is the smallest, and the axial residual strain of the specimen with 56 times of dry–wet cycle is the largest. Under the same loading–unloading cycles, the axial residual strain of RRFC specimens decreases slightly and then increases with the number of dry–wet cycles. Taking the first cycle of each group of specimens as an example, the axial residual strain of RRFC specimens from small to large is 7 times < 0 time < 14 times < 28 times < 56 times. This is because at the beginning of the dry–wet cycle, the initial pores inside the RRFC specimen are filled with C—S—H gel and chloride crystals, so the volume that can be compressed is reduced, but this reduction only exists in the initial stage of the dry–wet cycle. In the first few dry–wet cycles, pores and tiny cracks will be generated inside the material. Through constant alternation of wetting and drying, these pores and cracks may partially heal or close, thereby reducing strain. In addition, the material is a composite material, and the interface between different phases will be strengthened during the dry–wet cycle, thereby improving the strain capacity of the overall material and reducing the residual strain. As the dry–wet cycle progresses, the crystals and reaction products inside the specimen accumulate, increasing pores, cracks penetrating, mechanical properties beginning to degrade, and the resistance to deformation decreasing. The axial residual strain increases rapidly with the number of dry–wet cycles.

Fatigue damage strength analysis

The peak stress obtained in the uniaxial compression test is recorded as the uniaxial compressive strength fc, and the corresponding peak strain is εfc. The stress at the specimen's failure time after cyclic loading and unloading is recorded as the fatigue failure strength fp, and the corresponding fatigue failure strain is recorded as εfp. The ratio of fatigue failure strength to uniaxial compressive strength of RRFC specimens under the same number of dry–wet cycles is defined as the fatigue resistance coefficient Kp. The expression formula is as follows:

In the formula: Kf is the fatigue resistance coefficient of concrete specimens; fp is the strength (MPa) when the specimen is damaged after cyclic loading and unloading; fc is the specimen’s failure strength (MPa) without cyclic loading–unloading.

The relationship between uniaxial compressive strength and fatigue failure strength ofRRFC specimens in clear water solution and chloride salt solution under different dry–wet cycles was drawn by origin software, as shown in Fig. 7.The drawing software version used is OriginPro 2019. URL: https://www.originlab.com.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the uniaxial compressive strength of RRFC specimens initially increased and then decreased with an increasing number of dry–wet cycles. The peak compressive strength was observed during the 7th dry–wet cycle. In contrast, the fatigue failure strength of the specimens did not exhibit a clear growth phase. During the first seven dry–wet cycles, fatigue failure strength remained relatively stable, followed by a rapid decline in the middle cycles, after which it gradually stabilized. Furthermore, when comparing RRFC specimens in clear water to those in a chloride salt solution, it was evident that the deterioration of fatigue failure strength was more severe in the chloride environment. The fatigue resistance coefficient showed a more significant change as the deterioration progressed. For example, compared with before the dry–wet cycle, when the number of dry–wet cycles was 14 times, 28 times and 56 times, and the temperature of the clear water solution was 20 °C, the fatigue failure strength of the RRFC specimens decreased by 9.06, 21.7 and 28.57%, respectively. When the temperature of the chloride solution was 20 °C, the fatigue failure strength of the RRFC specimens decreased by 10.48, 23.80 and 30.59%, respectively. This is because when the cyclic loading and unloading test was carried out on the RRFC specimens at the initial stage of the dry–wet cycle, the cement hydration reaction of the specimens was more thorough and complete. The internal pores of the specimens were filled with C—S—H gel and chloride salt crystals, enhancing their uniaxial compressive strength and fatigue resistance. The rubber incorporated in the specimens provides high elasticity, which mitigates damage during cyclic loading and unloading, ultimately improving fatigue failure strength. However, the concrete specimens experienced some damage in the middle to late stages of the dry–wet cycle, which compounded the effects of repeated loading and unloading during testing. This combination of stresses significantly reduced the fatigue damage strength of the RRFC specimens. In chloride salt solution environments, the effects of the dry–wet cycle—such as increased internal voids, crack propagation, and surface spalling of cement mortar—were more severe compared to specimens exposed to clear water. Consequently, the fatigue damage observed during cyclic loading and unloading was more pronounced, resulting in a lower fatigue failure strength for these specimens.

Under the same dry–wet cycle conditions, the fatigue failure strength of RRFC specimens is lower than their uniaxial compressive strength. Additionally, the fatigue resistance coefficient of these specimens decreases rapidly in the early stages of dry–wet cycling but gradually stabilizes as the number of cycles increases. Furthermore, higher temperatures correspond to a lower fatigue resistance coefficient for the RRFC specimens, making them more susceptible to internal fatigue damage from repeated loading and unloading. For example, when the number of dry–wet cycles is 0, 7, 14, 28 and 56 times, and the temperature is 20 °C in the clear water solution, the fatigue resistance coefficient of the RRFC specimen is 0.94, 0.91, 0.86, 0.85 and 0.87; the fatigue resistance coefficients of RRFC specimens were 0.94, 0.93, 0.84, 0.83 and 0.85 in clear water at 60 °C. The fatigue resistance coefficients of RRFC specimens were 0.89, 0.82, 0.86, 0.81 and 0.84 in the clear water solution at 80 °C.This is because the higher the solution temperature, the faster the thermal motion of water molecules and chloride ions, the faster the diffusion rate of chloride ions, the particles inside the RRFC specimen are easily brought into the solution, and the solubility of the hydration products increases, increasing internal osmotic pressure, an increase in pore gaps, and a greater damage to the internal structure. At the initial stage of cyclic loading and unloading, with the increase of loading stress, the holes and cracks existing in the concrete and generated by dry–wet cycle damage are compacted. Then the internal micro-cracks will continue to expand and induce new cracks. During the loading and unloading process of cyclic stress, the specimen experiences fatigue damage, ultimately resulting in a reduction of its fatigue failure strength. As the solution temperature increases, the internal fatigue damage within the specimen becomes more pronounced, leading to a further decrease in fatigue strength.

Study on the microscopic mechanism of RRFC

SEM scanning electron microscope and XRD diffraction test were carried out on the specimens after the test, and the internal mechanism of RRFC specimens after dry–wet cycle was observed and analyzed from a microscopic perspective.

The microstructure and analysis of RRFC specimens without dry–wet cycle

Figure 8a,b shows the microstructure of the RRFC specimens without undergoing wet-dry cycling damage. It can be observed that the bonding within the RRFC specimens is relatively tight at this stage; however, there are a certain number of pores and gaps present within the concrete that has not undergone wet-dry cycling damage. This is due to the existence of pores and gaps during the concrete pouring process, which causes initial damage and provides pathways for subsequent chloride solution erosion of the concrete samples. Additionally, it is noted that there are voids around the rubber particles. This is because rubber particles do not participate in the cement hydration reaction, resulting in a lack of strong chemical bonding. Instead, the interface transition zone between the rubber particles and the cement matrix relies on the physical bonding force generated by C—S—H gel. The voids present between the rubber particles and the cement matrix also provide space for the rubber particles to exert their high elasticity, alleviating the concentration of stress. Therefore, an appropriate and uniform distribution of rubber particles in the concrete can effectively mitigate the propagation of cracks in the cement matrix, thereby improving the toughness of the RRFC specimens. From Fig. 8c,-d, it can be seen that the fibrous and flocculent C—S—H gel significantly fills the pores and cracks within the concrete, enhancing its density.

The micro-morphology and analysis of RRFC specimens under dry–wet cycle erosion conditions

The internal microstructure of RRFC specimens after 56 dry–wet cycles in 20 °C chloride solution was selected for SEM scanning, which was more in line with the actual situation of concrete highway tunnels in coastal areas. At the same time, 56 dry–wet cycles can clearly understand the internal microstructure of RRFC after serious damage, and better understand the resistance of RRFC to chloride erosion. Figure 9 shows the internal micro-morphology of RRFC specimens under wet-dry cycles of 56 times in chloride solution at 20 °C. Compared with the RRFC without erosion and dry–wet damage in Fig. 8, the damage in Fig. 9 shows that more penetrating cracks and larger pores have been formed inside the specimen. The cement-based material originally bonded by C—S—H gel has been decomposed into regions, and the structure has become loose.

The deterioration of the concrete specimens is primarily due to the effects of wet-dry cycling, which causes moisture to continuously infiltrate and evaporate from within the specimens. This process leads to an increase in voids and cracks, reducing the cohesive and frictional forces between the internal particles. Consequently, particles begin to migrate within the pores, creating osmotic pressure that undermines the bonding strength of the concrete. Additionally, the specimens underwent wet-dry cycling in a chloride solution, which chemically erodes the concrete, damaging the bond between the cement mortar and rubber. In the later stages of the wet-dry cycle, the reaction between the specimens and chloride solution results in the formation of a substantial amount of C3A·CaCl2·10H2O (F salt) accumulating in the pores. This accumulation generates significant expansive forces, leading to the formation of new cracks within the concrete and accelerating the ingress of chloride ions. The presence of C3A·CaCl2·10H2O observed in Fig. 9 corroborates that the deterioration of the specimens under the combined effects of chloride and wet-dry cycling is due to the synergistic effects of repeated crystallization and chemical erosion by chlorides. At this point, the tensile strength provided by the cement matrix and PVA fibers is insufficient to mitigate the cumulative damage, resulting in increased internal porosity and crack development. However, it is noteworthy that the cracks observed near the rubber particles were effectively blocked in their propagation paths by the rubber itself. This phenomenon results in crack blunting and a reduction in stress concentration, thereby slowing down the penetration of chloride ions. As a result, the rubber component imparts enhanced resistance to chloride erosion in the RRFC specimens.

XRD diffraction test results and analysis

The XRD diffraction spectrum of the RRFC specimen subjected to wet-dry cycles in an 80 °C chloride salt solution is shown in (Fig. 10). Based on the SEM microscopic morphology analysis of the RRFC specimen, it can be observed that the hydration reaction of the cement has led to a significant presence of calcium ions in the analyzed area of the specimen, primarily in the forms of Ca(OH)2 and C—S—H. This is attributed to the high reactivity of the silica (SiO2) in the rice husk ash present in the specimen, which reacts with Ca(OH)2 generated during the hydration process to produce a substantial amount of C—S—H gel. This process promotes the complete hydration of the cement, resulting in a reduction of Ca(OH)2 content over time, thereby validating the changes in the amounts of Ca(OH)2 and C—S—H.

Furthermore, comparing the different stages of the wet–dry cycle, the mass percentages of Ca2+ and Si4+ within the RRFC specimen are found to be similar. In the initial stages, before and shortly after the onset of wet-dry cycling, there is a considerable amount of Ca(OH)2 present. As the wet-dry cycling continues, a transformation occurs where Ca(OH)2 is converted into C—S—H gel, which provides bonding strength at the interface between the rubber and the cement mortar, enhancing density.

This indicates that the presence of rice husk ash in the RRFC specimen facilitates the cement hydration reaction and continuously generates C—S—H gel during the hydration process. This gel fills the pores and cracks, ultimately forming a dense structure throughout the material.

Mechanism analysis of RRFC resistance to dry–wet cycle/chloride corrosion

Through the above comparative analysis of the test results, it can be concluded that although the mass, relative dynamic elastic modulus, and strength of RRFC specimens undergo two processes of increasing first and then decreasing with the increase of the number of dry–wet cycles under dry–wet cycles at different temperatures, the magnitude of change is different. The following is an analysis of the mechanism of this phenomenon from both physical and chemical aspects based on the micro-morphology changes of RRFC specimens during the dry–wet cycle process.

Chemical mechanism

The rice husk ash in the RRFC specimen contains a large amount of amorphous SiO2, which has high pozzolanic properties. After the cement hydration reaction produces Ca(OH)2, SiO2 reacts with Ca(OH)2 to form C—S—H gel. The liquid CaO concentration around the cement material is reduced at this time, thereby accelerating the cement hydration reaction. The specific reaction equation is as follows:

The C—S—H gel formed by this reaction improves the compactness of the RRFC specimen. It reduces the presence of Ca(OH)2, which is why the mass, relative dynamic elastic modulus, and strength of the specimen are increased at the beginning of the dry–wet cycle. At the same time, the rate of chloride ion erosion of concrete specimens is reduced, and the channel is reduced, which significantly improves the ability of RRFC specimens to resist chloride salt erosion. The incorporation of rice husk ash optimizes the gradation of RRFC specimens, in which the highly active SiO2 and the crystal of cement clinker further complete the reorganization of the secondary structure, and the increase of C—S—H gel makes the bonding of the interface transition zone closer. This shows that adding an appropriate amount of rice husk ash significantly enhances concrete specimens' mechanical properties, toughness, and corrosion resistance.

During the pouring and curing process of RRFC specimens, the hydration reaction of cement generates hydration products such as Ca(OH)2, C—S—H gel, and Aft, which fills the internal pores and cracks of the specimens, increases the compactness of the specimens, and slows down the rate of chloride ion erosion. In the dry–wet cycle, chloride salt will form crystallization erosion on concrete. A large amount of crystallization will form inside the specimen to fill its internal pores and cracks. At the end of the dry–wet cycle, the chloride salt and the specimen react to generate a large amount of C3A·CaCl2·10H2O (F salt) to generate expansion force, which causes the new crack of the specimen to create and develop, resulting in a decrease in the strength of the specimen.

Physical mechanism

The rubber particles in the RRFC specimen are an organic material with high elasticity, slight compressibility, and non-hydrophilicity. Compared with inorganic materials such as sand and gravel, the rubber particles in the RRFC specimen have smaller hardness and lighter weight, and the bonding force with cement mortar is smaller, so the strength of the RRFC specimen is smaller than that of ordinary concrete. Due to the non-hydrophilicity of rubber, the incorporation of rubber into the concrete test block will produce bubbles, increase defects, complicate the structure of the interface transition zone of the test piece, and reduce the mechanical properties of the test piece. It can be seen from the SEM electron microscope that the interfacial transition zone between rubber particles and cement mortar is pronounced. The cement hydrate and gel form a physical bond. This bonding force is lighter than the chemical bonding force. The formed interfacial transition zone becomes a relatively weak area in the specimen. More micropores and microcracks exist than in other places, resulting in defects. However, the rubber material improves the toughness, corrosion resistance, and impact resistance of RRFC specimens. In the dry–wet cycle erosion, the excellent flexibility of rubber particles effectively alleviates the damage caused by the immersion and drying of water molecules and the expansion force generated by chloride crystallization. In the process of cyclic loading and unloading, the high elasticity of rubber particles effectively alleviates the damage caused by repeated loading and unloading and adjusts the internal stress redistribution of the specimen through its volume change so that RRFC shows excellent fatigue resistance. The PVA fiber in the RRFC specimen constitutes a random three-dimensional spatial grid, which effectively hinders the migration channel of chloride ions and the development of cracks, alleviates the stress concentration phenomenon, disperses the tip stress of cracks, and prevents the floating of rubber particles. Rice husk ash with a large specific surface area provides a nucleation point for cement hydration reaction, plays the role of micro aggregate, fills the internal pores of the specimen, and optimizes the particle gradation of the specimen.

Conclusion

-

1. After different numbers of dry–wet cycles, the axial peak strain of RRFC specimens during the 50th load-unload cycle is generally higher than that of the 1st cycle. The axial peak strain increases the most after 14 dry–wet cycles, reaching an increase of 11.73%. Overall, specimens subjected to 7 dry–wet cycles exhibit the lowest axial peak strain, while those subjected to 56 cycles show the highest axial peak strain.

-

2. Under the same number of load-unload cycles, the axial residual strain of RRFC specimens initially decreases and then increases with the number of dry–wet cycles. This is because the more dry–wet cycles there are, the more internal pores develop within the specimen, leading to greater axial residual strain.

-

3. The fatigue failure strength of RRFC specimens decreases and gradually stabilizes as the number of dry–wet cycles increases. Compared to RRFC specimens in pure water, those in chloride salt solutions exhibit more severe deterioration in fatigue failure strength, a lower fatigue resistance coefficient, and greater variation. Higher temperatures result in a relatively lower fatigue resistance coefficient for RRFC specimens, making them more prone to internal fatigue damage.

-

4. At the initial stage of cyclic load-unload testing, the pre-existing pores and cracks, along with those induced by dry–wet cycle damage within the concrete, are compacted. Subsequently, microcracks continue to extend and induce new cracks. During the cyclic loading and unloading process, specimens develop fatigue damage, ultimately leading to a decrease in fatigue failure strength. The uniformly distributed rubber particles in the concrete effectively mitigate the damage caused by cyclic stress, enhancing the toughness of RRFC specimens. They also effectively block crack propagation paths, reduce stress concentration, and slow down the intrusion of chloride ions, providing RRFC specimens with good resistance to chloride salt erosion.

-

5. The incorporation of rice husk ash optimizes the gradation of RRFC specimens. The high-activity SiO2 further reconfigures the secondary structure of the cement clinker crystals, and the increased C—S—H gel tightens the bonding in the interfacial transition zone. The large specific surface area of the rice husk ash provides nucleation points for the cement hydration reaction, functioning as micro-aggregates to fill internal pores, optimize particle gradation, and enhance the erosion and fatigue resistance of RRFC specimens. PVA fibers form a random three-dimensional spatial network within the RRFC specimens, alleviating stress concentration, dispersing crack tip stress, and preventing the flotation of rubber particles, thus exhibiting excellent fatigue resistance.

Data availability

Data will be provided by corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sathsara, K., Castillo, R. & Louise, C. Evaluation of the optimal concrete mix design with coconut shell ash as a partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 401, 132978 (2023).

Guo, J., Liang, X., Wang, X., Fan, Y. & Liu, L. Potential bene fits of limiting global warming for the mitigation of temperature extremes in China. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00412-4 (2023).

Madinah, N. Population growth and economic development : Unemployment challenge for Uganda. World J. Soc. Sci. Res. 7, 8–25 (2020).

Du, Z. & Wang, Y. Does energy-saving and emission reduction policy affects carbon reduction performance ? A quasi-experimental evidence in China. Appl. Energy 324, 119758 (2022).

Shi, Q. & Xu, W. Low-Carbon Path Transformation for Different Types of Enterprises under the Dual-Carbon Target (Vide Leaf, 2023).

Gajera, Z. R., Verma, K., Tekade, S. P. & Sawarkar, A. N. Bioresource technology reports kinetics of co-gasification of rice husk biomass and high sulphur petroleum coke with oxygen as gasifying medium via TGA. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 11, 100479 (2020).

Wang, M., Li, T., Xiao, Y. & Wang, W. Study of chemical looping co-gasification of lignite and rice husk with Cu–Ni oxygen carrier. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 16, 1127–1134 (2021).

Choudhary, M. et al. Journal of the Indian chemical society thermal kinetics and morphological investigation of alkaline treated rice husk biomass. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 99, 100444 (2022).

Faried, A. S., Mostafa, S. A., Tayeh, B. A. & Tawfik, T. A. The effect of using nano rice husk ash of different burning degrees on ultra-high-performance concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 290, 123279 (2021).

Jittin, V., Minnu, S. N. & Bahurudeen, A. Potential of sugarcane bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material and comparison with currently used rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 273, 121679 (2021).

Abbass, M., Singh, D. & Singh, G. Materials today : Proceedings Properties of hybrid geopolymer concrete prepared using rice husk ash, fly ash and GGBS with coconut fiber. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 4964–4970 (2021).

Reddy, K. R., Harihanandh, M. & Murali, K. Materials today : Proceedings strength performance of high-grade concrete using rice husk ash ( RHA ) as cement replacement material. Mater. Today Proc. 46, 8822–8825 (2021).

Gastaldini, A. L. G., Silva, M. P., Zamberlan, F. B. & Neto, C. Z. M. Total shrinkage, chloride penetration, and compressive strength of concretes that contain clear-colored rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 54, 369–377 (2014).

He, Z., Li, L. & Du, S. Creep analysis of concrete containing rice husk ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 80, 190–199 (2017).

Park, C., Salas, A., Chung, C. & Lee, C. J. Freeze-thaw resistance of concrete using acid-leached rice husk ash. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 18, 1133–1139 (2014).

Pan, Y. et al. Pyrolytic transformation behavior of hydrocarbons and heteroatom compounds of scrap tire volatiles. Fuel 276, 118095 (2020).

Zia, A., Zhang, P. & Holly, I. Long-term performance of concrete reinforced with scrap tire steel fibers in hybrid and non-hybrid forms : Experimental behavior and practical applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134011 (2023).

Pongsopha, P., Sukontasukkul, P., Maho, B. & Intarabut, D. Sustainable rubberized concrete mixed with surface treated PCM lightweight aggregates subjected to high temperature cycle. Constr. Build. Mater. 303, 124535 (2021).

Jiang, Y. & Zhang, S. Experimental and analytical study on the mechanical properties of rubberized self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 329, 127177 (2022).

Valizadeh, A., Hamidi, F., Aslani, F., Uddin, F. & Shaikh, A. The effect of specimen geometry on the compressive and tensile strengths of self-compacting rubberised concrete containing waste rubber granules. Structures 27, 1646–1659 (2020).

Yang, G. et al. Creep behavior of self-compacting rubberized concrete at early age. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34, 1–11 (2022).

Chu, L., Wang, S., Li, D., Zhao, J. & Ma, X. Case studies in construction materials cyclic behaviour of beam-column joints made of crumb rubberised concrete ( CRC ) and traditional concrete ( TC ). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00867 (2022).

Jin, H., Tian, Q., Li, Z. & Wang, Z. Ability of vibration control using rubberized concrete for tunnel. Constr. Build. Mater. 317, 125932 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Rubberized geopolymer concrete : Dependence of mechanical properties and freeze-thaw resistance on replacement ratio of crumb rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 310, 125248 (2021).

Engin, E. & Reports, E. Contribution to the study of the durability of rubberized concrete in aggressive. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 30, 111–129 (2020).

Gerges, N. N., Issa, C. A. & Fawaz, S. A. Case studies in construction materials rubber concrete : Mechanical and dynamical properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 9, e00184 (2018).

Lin, Q., Liu, Z., Sun, J. & Yu, L. Comprehensive modification of emulsified asphalt on improving mechanical properties of crumb rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 369, 130555 (2023).

Valentin, J., Vasiliev, Y. E., Kowalski, K. J. & Zhang, J. Research on the properties of rubber concrete containing surface-modified rubber powders. J. Build. Eng. 35, 101991 (2021).

Youssf, O. et al. Influence of mixing procedures, rubber treatment, and fibre additives on rubcrete performance. J. Compos. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs3020041 (2019).

Chan, C. W., Yu, T., Zhang, S. S. & Xu, Q. F. Compressive behaviour of FRP-confined rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 211, 416–426 (2019).

Wang, J., Dai, Q., Si, R. & Guo, S. Investigation of properties and performances of polyvinyl alcohol ( PVA ) fiber-reinforced rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 193, 631–642 (2018).

Devi, M., Kannan, L., Ganeshkumar, M. & Venkatachalam, T. S. Flexural behavior of polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced concrete. SSRG Int. J. Civ. Eng. 4, 27–30 (2017).

Noushini, A., Samali, B. & Vessalas, K. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol ( PVA ) fibre on dynamic and material properties of fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Buid. Mater. 49, 374–383 (2013).

Du, E., Wang, Y., Sun, J. & Yang, S. Annales de chimie : Science des materiaux experimental analysis on ductility of polyvinyl alcohol fibre reinforced concrete frame joints. ACSM 43, 17–22 (2019).

Al-ayish, N., During, O., Malaga, K., Silva, N. & Gudmundsson, K. The influence of supplementary cementitious materials on climate impact of concrete bridges exposed to chlorides. Constr. Build. Mater. 188, 391–398 (2018).

Van Den Heede, P., De Keersmaecker, M., Elia, A., Adriaens, A. & De Belie, N. Service life and global warming potential of chloride exposed concrete with high volumes of fly ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 80, 210–223 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Zhang, H., Lv, W., Zhang, J. & Wang, N. Micro-structure characteristics of unsaturated polyester resin modified concrete under fatigue loads and hygrothermal environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 296, 123766 (2021).

Xu, Y., Yang, R., Chen, P., Ge, J. & Liu, J. Case studies in construction materials experimental study on energy and failure characteristics of rubber-cement composite short-column under cyclic loading. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00885 (2022).

Youssef, Z., Jacquemin, F., Gloaguen, D. & Guille, R. A multi-scale analysis of composite structures : Application to the design of accelerated hygrothermal cycles. Compos. Str 82, 302–309 (2008).

Zheng, X. H., Huang, P. Y., Chen, G. M. & Tan, X. M. Fatigue behavior of FRP—Concrete bond under hygrothermal environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 95, 898–909 (2015).

Song, Y. et al. Behaviour of treated rubberised fiber concretes at higher temperatures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/620/1/012080 (2019).

Maho, B., Sukontasukkul, P., Jamnam, S., Yamaguchi, E. & Fujikake, K. Effect of rubber insertion on impact behavior of multilayer steel fiber reinforced concrete bulletproof panel. Constr. Build. Mater. 216, 476–484 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. A robust mix design method for self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 352, 128927 (2022).

Oyebisi, S., Igba, T., Raheem, A. & Olutoge, F. Case studies in construction materials predicting the splitting tensile strength of concrete incorporating anacardium occidentale nut shell ash using reactivity index concepts and mix design proportions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 13, e00393 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. structural foamed concrete with lightweight aggregate and polypropylene fiber : Product design through orthogonal tests. Polym. Polym. Compos. 24, 173–178 (2016).

Sabarish, K. V. & Parvati, T. S. Materials today : Proceedings an experimental investigation on L9 orthogonal array with various concrete materials. Mater. Today Proc. 37, 3045–3050 (2021).

Irmukhametova, G. S., Bekbayeva, L., Bekbayeva, A. & Mun, G. A. The effect of poly vinyl chloride-co-vinyl acetate crosslinking agent on mechanical properties of acrylic primer for concrete substrate application. Orient J Chem., 0–5 (2018).

Liu, K. et al. Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of fiber reinforced metakaolin-based recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 294, 123554 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Anhui Key Laboratory of Mining Construction Engineering, Anhui University of Science and Technology, HuaiNan, Anhui, China, 232001 (No. GXZDSYS2022105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jianyong Pang: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Heng Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing-original draft. Yihua Xu: Software, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation. Jiuqun Zou: Resources, Visualization. Jihuan Han: Formal analysis, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Pang, J., Zou, J. et al. Erosion degradation analysis of rice husk ash-rubber-fiber concrete under hygrothermal environment. Sci Rep 14, 22700 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71939-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71939-6