Abstract

The adverse pregnancy outcomes, including recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA), are strongly correlated with water-soluble vitamins, but how to predict RSA occurrence using them remains unsatisfactory. This study aims to investigate the possibility of predicting RSA based on the baseline levels of water-soluble vitamins tested by ultra-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. A total of 918 pregnant women was consecutively enrolled in this cross-sectional study. According to the miscarriage numbers, they were divided into normal first pregnancy (NFP, n = 608), once spontaneous abortion (OSA, n = 167), and continuous spontaneous abortion (CSA, n = 143) groups. The Cox proportional-hazards regression model was employed to establish a risk model for predicting RSA. The RSA occurrence was 6.54% in overall pregnant women, with a prevalence of 12.57% in the OSA group and 27.27% in the CSA group. Significant differences were observed in baseline deficiencies of vitamin B3, B5, B6, and B9 among NFP, OSA, and CSA groups (χ2 = 12.191 ~ 37.561, all P < 0.001). Among these vitamins, B9 (HR = 0.89 and 0.88, all P < 0.001) and B6 (HR = 0.83 and 0.78, all P < 0.05) were identified as independent factors in both the OSA and CSA groups; whereas B5 was identified as an additional independent factor only in the CSA group (HR = 0.93, P = 0.005). The Cox proportional-hazards model established using these three vitamins exhibited poor or satisfactory predictive performance in the OSA (Sen = 95.2%, Spe = 39.0%) and CSA (Sen = 92.3%, Spe = 60.6%) groups, respectively. However, B5, B6, and B9 compensatory levels were not associated with RSA occurrence (all P > 0.05). Our study presents a highly sensitive model based on mass spectrometry assay of baseline levels in B vitamins to predict the RSA occurrence as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spontaneous abortion (SA), an accidental miscarriage occurring without external intervention prior to 20 ~ 24 weeks gestational age, affects more than 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies1. It can subdivide into threatened, inevitable, incomplete, missed, septic, and complete abortions1,2, and manifest imperceptible embryo loss even life-threatening shock during a pregnancy course2. When consecutive spontaneous pregnancy losses occur, it is referred to as recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA), which affects approximately 1 ~ 5% of reproductive women3,4. The definition of RSA in relation to the number of miscarriages varies among different countries. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine define RSA as two or more accidental miscarriages, while the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists defines it as three or more4,5. Additionally, recent epidemiological surveys provide evidence to suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has potentially accelerated the occurrence of RSA, with a prevalence rate reaching up to 6.5 ~ 9.5%6,7.

Although the etiology of RSA can often be attributed to fetal, maternal, or external factors, in many cases, the specific etiology remains never to be identified. Numerous studies have demonstrated a significant association between water-soluble vitamins and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including anemia, nausea and vomiting, and malnutrition in pregnant women, and/or fetal neural tube defects, other central system disorders, and poor embryonic development8,9,10. The water-soluble vitamins include nine compounds, that is, eight B vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, and B12) and one vitamin C11. Of them, B vitamins have been found to potentially induce chromosomal abnormalities12,13, as well as a broad spectrum of endocrine, immune, and metabolic disorders14,15, thereby impeding proper embryo development during pregnancy, potentially increasing abortion risk. The systematic review and Meta-analysis on vitamin and mineral Supplementation during pregnancy have demonstrated a significant impact of vitamin B9 supplementation on enhancing pregnancy outcomes16,17,18, while the role of other vitamin supplementation remains a subject of controversy19,20,21,22.

Up to now, the progress in predicting and preventing RSA is unencouraging, despite the relative simplicity of its diagnosis3. The lack of standardized definitions, the uncertainties surrounding pathogenesis, and the highly variable clinical presentation, as well as the compensatory vitamin levels, and the accuracy of the measurement technique, all contribute to challenges in predicting RSA. The isotope-dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry offers a highly sensitive, selective, and specific testing method for water-soluble vitamins23. Therefore, based on this technique for assessing the baseline levels of water-soluble vitamins in pregnant women, this study aims to investigate the potential for predicting RSA. According to the number of accidental miscarriages, we defined once SA (OSA) as only once occurrence, and continuous SA (CSA) as twice or more occurrences. Our OSA definition is consistent with the definition of RSA in most countries.

Methods

Participants

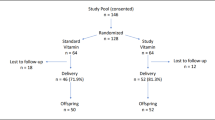

The study enrolled pregnant women with a SA history who underwent long-term follow-up at Mianyang Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China from Jan. 2021 to Dec. 2023. Inclusion criteria: (1) pregnant women with clinically recognized pregnancies at 4 and 6 gestational weeks; (2) their baseline levels of water-soluble vitamins were tested at 4–6 gestational weeks; (3) with well-documented pregnancy outcomes. Exclusion criteria: (1) pregnant women who had previously undergone an induced abortion or were deciding an artificial abortion based on personal choice; (2) pregnant women who had taken complex or individual B vitamins, excluding vitamin 9, prior to conception and prior to the examination of water-soluble vitamins; (3) pregnant women requiring termination of their pregnancies due to severe illness; (4) pregnant women who were lost to follow-up. During the same period, pregnant women with a first pregnancy further a successful delivery were consecutively enrolled referring to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for pregnant women with SA history.

Finally, a total of 918 pregnant women was enrolled in this study (See Supplementary Fig. 1). According to the SA experience, all participants were divided into three groups: normal first pregnancy (NFP, pregnant women with a first pregnancy further a successful delivery, n = 608), once spontaneous abortion (OSA, pregnant women with once SA history, n = 167), and continuous spontaneous abortion (CSA, pregnant women with two or more SA history, n = 143). After conducting baseline testing, the OSA and CSA groups were administered with a low dosage of B complex vitamin supplementation until 24 gestational weeks. The daily dosage of B complex vitamin supplementation was as follow: 1.4 mg of B1, 1.4 mg of B2, 36 mg of B3, 4 mg of B5, 7 mg of B6, 30 μg of B7, 360 μg of B9, and 6 μg of B12.

Sample collecting and processing

Aliquots of 3.0 ml fasting blood were collected in an SST-II vacuum tubes (BD, USA) during 4 ~ 6 gestational weeks and after 4 weeks of vitamin supplementation. Serum was separated within 30 min via centrifuging at approximately 1500 × g for 10 min, and used for the quantification of water-soluble vitamin levels within a timeframe of 3 days. Prior to quantification, the serum was stored at − 20 °C.

Before mass spectrometry, the thawed serum was preprocessed using a water-soluble vitamin assay kit (CAT.NO. YS20020009, Shandong Yingsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., CHN). The sample releaser III from the kit was mixed with the freshly dissolved internal standard concentrate at a volume ratio of 200:1. 60 μl of this mixture was combined with 60 μl of serum and vortexed for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 12000 × g for an additional 5 min. Subsequently, 70 μl of supernatant was transferred into a microplate, and sealed for chromatographic analysis.

Chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay of water-soluble vitamin

Nine water-soluble vitamins were measured on a EXT9050MD ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) (Shandong Yingsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., CHN). The chromatography conditions were as follows: C18 column at 40 °C, 30 μl injection volume, and density gradient elution with 0.5 ml/min flow rate by mobile phase A of 0.1% formic acid in deionized water and mobile phase B of 0.1% formic acid in methanol. The percentage of mobile phase B was 1% from 0 to 1 min, 98% from 1 to 2 min, 98% from 2 to 3.5 min, 1% from 3.5 to 4.5 min, 0% from 4.5 to 5.0 min.

The mass spectrometry conditions were as follows: positive ion mode of electrospray ion trap, electrospray voltage 3500 V, ionization temperature 350 °C, sheath gas (GS1) 50psi, aux gas 10psi. The cluster removal voltages and collision voltages were 30 V and 21 V for vitamin B1, 60 V and 31 V for vitamin B2, 45 V and 28 V for vitamin B3, 40 V and 21 V for vitamin B5, 48 V and 29 V for vitamin B6, 37 V and 23 V for vitamin B7, 46 V and 25 V for vitamin B9, 45 V and 55 V for vitamin B12, 25 V and 14 V for vitamin C, respectively. Mass spectrometry scan used a multiple reaction monitoring mode with the range from 150 to 500 m/z, and the rate of 1000 Da/s. Chromatograms and process data were analyzed using TraceFinder™ modern data visualization software (version 4.1, Thermo). Via monitoring the paired Q1/Q3 ion mass, vitamin B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12, and C were distinctly separated and identified with the retention time of 1.47 min, 5.14 min, 1.81 min, 3.70 min, 2.92 min, 5.22 min, 4.30 min, 5.26 min, and 0.81 min, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Cut-off definitions of B vitamins during early pregnancy

The water-soluble vitamin level was determined using the isotope-dilution internal standard method. The chromatographic peak area ratio was calculated between the sample (or standard) and the internal standard. For each water-soluble vitamin, five standards with gradient concentration were used to draw a “peak area ratio-concentration” curve, which was used to quantify the concentration in sample.

The cut-off values for vitamin B9 and B12 deficiencies during early pregnancy adopted the BOND project and WHO recommendation24,25,26,27, which were < 10 ng/mL and < 20 ng/dL respectively. While the cut-off values for vitamin B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, and B12, and C deficiencies adopted the lower reference limit provided by the kit, which were < 0.5 ng/mL, < 3 ng/mL, < 12 ng/mL, < 10 ng/mL, < 0.5 ng/mL, and < 6 μg/mL, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in the MedCalc software v20.1 (MedCalc, Belgium) and SPSS software v22.0 (SPSS, USA). The levels of water-soluble vitamins were presented as median (P25, P75) [min, max]. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to analyze the differences among groups, and POST-HOC analysis was conducted for pairwise comparisons using the adjusted P value (Padj) to determine statistical significance. The deficiency rates were presented as n (%), and χ2 test was used to compare the group difference. The Kaplan–Meier curves were used to depict the occurrence of miscarriage among the entire population of pregnant women, as well as within the OSA and CSA groups. The Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to examine the hazard ratio of each vitamin and establish a risk model. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used for a two-tailed test.

Results

The baseline levels of nine water-soluble vitamins in three pregnant groups

The median, P25, P75, min, and max of eight vitamin levels in the three pregnant groups were listed in Table 1. There were significant differences in vitamin B1, B5, B6, B9, and B12 levels among three pregnant groups (χ2 = 9.445 ~ 65.634, all P < 0.01). Pairwise comparisons found that vitamin B1, B5, B6, B9, and B12 levels were lower in the CSA group than in the NFP group (z = 2.915 ~ 8.008, all Padj < 0.05), while only vitamin B1, and B5 levels were lower in the CSA group than in the OSA group (z = 2.656 and 4.368, both Padj < 0.05). Additionally, vitamin B5, B6, and B9 levels were lower in the OSA group than in the NFP group (z = 2.680 ~ 3.355, all Padj < 0.05). Except for vitamin B7, the levels of the other eight vitamins ranged widely within each pregnant group, with the exceptionally high individual outliers.

The prevalence of nine water-soluble vitamins deficiencies

According to the lower reference limit provided by the kit, or the BOND project and WHO recommendation, we analyzed the prevalence of nine water-soluble vitamins deficiencies. Vitamin B12 (76.7%), B6 (26.8%), B3 (22.8%), C (18.6%), B2 (8.0%) and B9 (7.8%) deficiencies exceeded 5% among overall pregnant women, moreover vitamin B5 (7.7%) and B9 (17.5) deficiencies were also significant in CSA group (Table 2). Only vitamin B3, B5, B6 and B9 deficiencies were significantly different among the three groups (χ2 = 12.191 ~ 37.561, all P < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons found that B3 deficiency was higher in the CSA group than in the NFP and OSA groups (χ2 = 9.202 and 9.927, both P = 0.002), while B5 and B6 deficiencies were higher in the OSA and CSA groups than in the NFP group (χ2 = 13.637 ~ 41.669, all P < 0.001).

Univariate risk analysis of each water-soluble vitamin to RSA

The RSA occurrence in overall pregnant women was 6.54% (60/918), with a prevalence of 12.57% (21/167) in the OSA group and 27.27% (39/143) in the CSA group. Fetal survival curve showed that the RSA occurrence was higher in the CSA group than in the OSA group (χ2 = 10.627, P = 0.001) (Fig. 1). The risk analysis of each water-soluble vitamin demonstrated that vitamin B5, B6, and B9 were the risk factors to RSA occurrence among both overall pregnant women (HR = 0.95, 0.87, and 0.87, all P < 0.001) and the CSA group (HR = 0.87, 0.71, and 0.85, all P < 0.01), while vitamin B6 and B9 were the risk factors to RSA occurrence among the OSA group (HR = 0.82 and 0.91, all P < 0.05) (Table 3). These results suggest that the miscarriage rate in the CSA group significantly increased, which may be involved in more influencing factors including vitamin B5 deficiency.

The fetal survival curve in overall pregnant women, OSA and CSA groups. Note OSA, once spontaneous abortions; CSA, continuous spontaneous abortions. The default duration for fetal survival in any surviving fetus was set at 40 gestational weeks. The corresponding cumulative miscarriage rate in each group is highlighted using a dot.

Comprehensive risk assessment of water-soluble vitamin deficiency to RSA occurrence

Under the confounding effect of age and the interaction of each water-soluble vitamin (Table 4), vitamin B9 was an independent factor among overall pregnant women, OSA, and CSA groups (HR = 0.87, 0.89, and 0.88, all P < 0.001); B6 was an independent factor among OSA, and CSA groups (HR = 0.83 and 0.78, all P < 0.05); while B5 was an independent factor only among CSA group (HR = 0.93, P = 0.005). These results suggest that the risk of water-soluble vitamin deficiencies contributing to miscarriage varies among pregnant women with different SA history, indicating the need for tailored treatment approaches.

Predictive power of water-soluble vitamins on RSA occurrence

According to the above analysis, we utilized the data of overall pregnant women to establish a Cox proportional-hazards model for predicting the RSA occurrence based upon vitamin B5, B6, and B9 levels: Prognostic index (PI) = − 0.020 × B5 − 0.143 × B6 − 0.123 × B9 (χ2 = 71.327, P < 0.001; C-index = 0.777, 95% CI = 0.722 ~ 0.831) (See supplementary Table 1 for the details about the baseline cumulative hazard). The cumulative RSA risks at the average levels of vitamin B5 (29.92 ng/mL), B6 (3.45 ng/mL), and B9 (22.17 ng/mL) were observed to range from 0.1 ~ 3.5% (Fig. 2A). The performance of this model for predicting miscarriage in the OSA group was relatively low, with an AUC of 0.704, a sensitivity of 95.2%, and a specificity of 39.0% (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the model exhibited a relatively high performance for predicting miscarriage in the CSA group, with an AUC value of 0.825, a sensitivity of 92.3%, and a specificity of 60.6% (Fig. 2C). Overall, the model demonstrated quite high sensitivity in predicting RSA for both OSA and CSA groups, with no significant difference observed between the two groups (χ2 = 1.134, P = 0.287). However, the model was more suitable for predicting RSA occurrence in the CSA group, as it exhibited significantly higher AUC (z = 2.056, P = 0.040) and specificity (χ2 = 14.549, P < 0.001).

The Cox proportional-hazards model based on baseline levels of vitamin B5, B6, and B9 to predict miscarriage risk. Note (A) Survival curve at mean baseline level of vitamin B5, B6, and B9, which cumulative RSA risks was 3.5% at 23 gestational weeks; (B) ROC curve of OSA vs. NFP, with sensitivity of 95.2% and specificity of 39.0% when maximum prediction accuracy; (C) ROC curve of CSA vs. NFP, with sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 60.6% when maximum prediction accuracy. NFP, normal first pregnancy; OSA, once spontaneous abortions; CSA, continuous spontaneous abortions.

Correlation of water-soluble vitamins with RSA occurrence after supplementation therapy

After 4 weeks of vitamin supplementation, only in the CSA group, the pregnant women with miscarriage exhibited significantly lower levels in vitamin B5 (z = − 2.828, P = 0.005) and B9 (z = − 2.453, P = 0.014) compared to the pregnant women with non-miscarriage (Table 5). However, their B5, B6, and B9 levels were not associated with RSA occurrence (all P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study focused on pregnant women who had experienced one or more SA. Using UHPLC-MS/MS, their baseline water-soluble vitamin levels were measured at the time of clinically recognized pregnancy. Our study revealed significant heterogeneity in baseline levels of almost all water-soluble vitamins, and evident deficiencies in multiple B vitamins and vitamin C among pregnant women, as well as risks of baseline levels in vitamin B5, B6 and B9 to the RSA occurrence. The most notable highlight was the successful development of an RSA prediction model based on these risky vitamins, which demonstrated a sensitivity exceeding 90% for predicting RSA in either OSA or CSA groups. However, this model displayed a lower specificity of 39.0% in the OSA group compared to a higher specificity of 60.6% in the CSA group. The prediction of miscarriage using water-soluble vitamins has posed a significant puzzle in this research field. Our achievement on the initial attempt may be attributed to the use of a UHPLC-MS/MS technique for precise quantification, the detection of baseline levels in water-soluble vitamins, the distinctiveness of the pregnant women group being focus on, and subgrouping the RSA pregnant women by number of miscarriages. In addition, the value of compensatory essential vitamin levels in predicting RSA occurrence is limited.

Numerous studies have reported the relationship between vitamin B9 and adverse pregnancy28,29. Vitamin B9, also known as folic acid, plays a crucial role in various cellular metabolic activities. Its deficiency can result in the occurrence of macrocytic anemia, mucositis, infertility, muscular weakness, cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, cancer, other related conditions30. Over the past two decades, numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that vitamin B9 supplementation significantly enhances pregnancy outcomes16,17,18, and continuous use of vitamin B9 during pregnancy also improved perinatal depression31. Despite some conflicting evidence32, vitamin B9 supplementation is now widely recommended and universally practiced among reproductive women for preconception planning or during pregnancy in many countries33,34,35. In this study, only 0.4% of the pregnant women exhibited vitamin B9 levels below the lower limit of reference (4.0 ng/mL), thereby confirming that a majority of pregnant women had initiated vitamin B9 supplementation prior to conception. However, owing to the heightened demand during pregnancy36, there can still be a relative deficiency in vitamin B9. Referring to the recommended optimal serum folate threshold for neural tube defect prevention37,38 and the BOND project and WHO recommendation24,25,26, we set a threshold of 10 ng/mL, and identified significantly relative deficiencies of vitamin B9 during pregnancy, especially in the CSA group of 17.5% (25/143). Taken together, adequate pre-pregnancy supplementation of vitamin B9 may serve as a potent intervention in facilitating the growth and development of embryos and fetuses. It is noteworthy that recent evidence suggested excessive vitamin B9 as potential risks of adverse genomic and epigenomic alterations39, thereby necessitating a consideration for continuous monitoring of maternal vitamin B9 levels during pregnancy.

Our study also revealed a significant insufficiency of vitamin B6 in pregnant women with different SA histories (ranging from 20.7 to 41.3%), and further it emerged as a crucial predictor for RSA. Vitamin B6, also known as pyridoxine, serves as a crucial cofactor regulating approximately 150 metabolic reaction processes of protein, glucose, lipids, neurotransmitters, and DNA40. Numerous studies have demonstrated the involvement of vitamin B6, B9, and B12 in methionine metabolism, resulting in the accumulation of homocysteine41,42. Elevated levels of homocysteine can lead to the occurrence of neural tube defect43, preeclampsia44,45, intrauterine growth retardation or fetal death44,45, and gestational diabetes mellitus46,47, as well as other factors contributing to miscarriages. Some scholar has suggested the preventive administration of vitamin B6 to reduce these complications48. But its role in preventing miscarriage remains controversial48,49. Our study findings indicated that vitamin B6 deficiency increase the risk for RSA in pregnant women with a history of at least one miscarriage, highlighting the importance of considering supplementation prior to planning subsequent pregnancies.

As for vitamin B5, also known as pantothenic acid, is essential for the synthesis of Coenzyme A, which plays a crucial role in various physiological processes such as energy metabolism from fats, carbohydrates, and proteins50. In general, the abundant dietary sources and infrequent deficiencies of vitamin B5 contribute to limited research on this nutrient, as well as a dearth of significant findings. It has been reported that the levels of vitamin B5 in the blood significantly decrease during pregnancy51, which is associated with a higher risk of low birth weight in offspring52. Although clinical evidence is extremely lacking, vitamin B5 deficiency has been observed to be associated with miscarriage in an old animal study53. Interestingly, our study revealed that vitamin B5 deficiency was extremely rare among overall pregnant women, but occurred to a certain extent in the CSA group (7.7%); so, it still posed a risk for the CSA group. Regarding the potential link between vitamin B5 deficiency and miscarriage in the CSA group, it could be attributed to factors such as fetal underdevelopment53, as well as maternal depression54,55, anxiety55, and severe malnutrition53. These conditions are commonly observed among reproductive women with continuous SA history1. Moreover, it has been indicated that pregnant women should maintain only the average level of vitamin B5, as an increased intake of more than 5.6 mg/day may lead to genome instability and subsequent teratogenicity54.

To the best of our knowledge, we successfully addressed the puzzle of utilizing B vitamins to predict RSA. Our prediction models, constructed using B5, B6, and B9, exhibited exceptional sensitivity and were deemed suitable for primary screening of RSA. Consequently, regular prenatal screening for B vitamins, particularly B5, B6, and B9, is imperative for ensuring pregnancy safety. However, the utilization of mass spectrometry for vitamin detection is not prevalent. Therefore, it is also imperative to explore alternative detection techniques that offer greater convenience compared to mass spectrometry.

The limitation of our study: (1) Our study retained only the NFP group as a control without women who experienced a miscarriage in their first pregnancy, which may have introduced bias into the conclusions. (2) The failure to investigate the exact etiology, which was unknown in most miscarriages, might introduce potential bias in the model applicability. (3) Although the proposed model demonstrated excellent sensitivity in predicting RSA, its unsatisfactory specificity resulted in significant false positives that cannot be disregarded, especially in OSA group.

Conclusion

Taken together, we developed for the first a Cox proportional-hazards model based on baseline levels of vitamin B5, B6, and B9 to predict miscarriage risk in pregnant women with a history of SA. On one hand, the model may facilitate the identification of pregnant women at high risk for RSA, thereby timely implementing individualized treatment and intervention. On the other hand, for the pregnant women at low risk for RSA identified by the model, the excessive vitamin supplementation should be avoided to prevent vitamin toxicity-related adverse events.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Griebel, C. P., Halvorsen, J., Golemon, T. B. & Day, A. A. Management of spontaneous abortion. Am. Fam. Physician 72(7), 1243–1250 (2005).

McBride, W. Z. Spontaneous abortion. Am. Fam. Physician 43(1), 175–182 (1991).

Dimitriadis, E., Menkhorst, E., Saito, S., Kutteh, W. H. & Brosens, J. J. Recurrent pregnancy loss. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 6(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00228-z (2020).

Green, D. M. & O’Donoghue, K. A review of reproductive outcomes of women with two consecutive miscarriages and no living child. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 39(6), 816–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1576600 (2019).

Potdar, N. & Iyasere, C. Early pregnancy complications including recurrent pregnancy loss and obesity. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 90, 102372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2023.102372 (2023).

Trostle, M. E., Penfield, C. A. & Roman, A. S. Adjustment of the spontaneous abortion rate following COVID-19 vaccination. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM. 4(1), 100511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100511 (2022).

Jacoby, V. L. et al. Risk of pregnancy loss before 20 weeks’ gestation in study participants with COVID-19. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225(4), 456–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.080 (2021).

Hanna, M., Jaqua, E., Nguyen, V. & Clay, J. B Vitamins: Functions and uses in medicine. Perm. J. 26(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/21.204 (2022).

Chawla, J. & Kvarnberg, D. Hydrosoluble vitamins. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 120, 891–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-4087-0.00059-0 (2014).

Fejzo, M. S. et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 5(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0110-3 (2019).

Said, H. M. & Nexo, E. Gastrointestinal handling of water-soluble vitamins. Compr. Physiol. 8(4), 1291–1311. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c170054 (2018).

Bascom, J. T. et al. Scientific impact of the national birth defects prevention network multistate collaborative publications. Birth Defects Res. 116(1), e2225. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.2225 (2024).

Fenech, M. F., Bull, C. F. & Van Klinken, B. J. Protective effects of micronutrient supplements, phytochemicals and phytochemical-rich beverages and foods against DNA damage in humans: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and prospective studies. Adv. Nutrit. (Bethesda, Md). 14(6), 1337–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2023.08.004 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Folate, Vitamin B6, and Vitamin B12 status in association with metabolic syndrome incidence. JAMA Netw. open. 6(1), e2250621. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50621 (2023).

Sechi, G., Sechi, E., Fois, C. & Kumar, N. Advances in clinical determinants and neurological manifestations of B vitamin deficiency in adults. Nutrit. Rev. 74(5), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv107 (2016).

Oh, C., Keats, E. C. & Bhutta, Z. A. Vitamin and mineral supplementation during pregnancy on maternal, birth, child health and development outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020491 (2020).

Mousa, A., Naqash, A. & Lim, S. Macronutrient and micronutrient intake during pregnancy: An overview of recent evidence. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020443 (2019).

Santander Ballestín, S., Giménez Campos, M. I., Ballestín Ballestín, J. & Luesma Bartolomé, M. J. Is supplementation with micronutrients still necessary during pregnancy? A review. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093134 (2021).

Bhowmik, B. et al. Vitamin D3 and B12 supplementation in pregnancy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Practice. 174, 108728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108728 (2021).

Gaskins, A. J. & Chavarro, J. E. Diet and fertility: A review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218(4), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.010 (2018).

Avram, C., Bucur, O. M., Zazgyva, A., Avram, L. & Ruta, F. Vitamin supplementation in pre-pregnancy and pregnancy among women-effects and influencing factors in romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148503 (2022).

Ali, M. A. et al. Dietary Vitamin B complex: Orchestration in human nutrition throughout life with sex differences. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193940 (2022).

Lamers, Y. Indicators and methods for folate, vitamin B-12, and vitamin B-6 status assessment in humans. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutrit. Metab. Care. 14(5), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328349f9a7 (2011).

Raiten, D. J. et al. Executive summary–biomarkers of nutrition for development: Building a consensus. Am. J. Clin. Nutrit. 94(2), 633s-s650. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.008227 (2011).

WHO. Serum and red blood cell folate concentrations for assessing folate status in populations (World Health Organization, 2015).

Allen, L. H. et al. Biomarkers of nutrition for development (BOND): Vitamin B-12 review. J. Nutrit. 148, 1995s–2027s. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxy201 (2018).

Wilson, R. D. & O’Connor, D. L. Guideline No. 427: Folic acid and multivitamin supplementation for prevention of folic acid-sensitive congenital anomalies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 44(6), 707–19.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2022.04.004 (2022).

George, L. et al. Plasma folate levels and risk of spontaneous abortion. Jama. 288(15), 1867–1873. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.15.1867 (2002).

Qin, X. Y., Ha, S. Y., Chen, L., Zhang, T. & Li, M. Q. Recent advances in folates and autoantibodies against folate receptors in early pregnancy and miscarriage. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234882 (2023).

Shulpekova, Y. et al. The concept of folic acid in health and disease. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26123731 (2021).

Jin, X. et al. Continuous supplementation of folic acid in pregnancy and the risk of perinatal depression-A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disorders 302, 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.080 (2022).

Lassi, Z. S., Salam, R. A., Haider, B. A. & Bhutta, Z. A. Folic acid supplementation during pregnancy for maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013(3), CD006896. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006896.pub2 (2013).

Njiru, H., Njogu, E., Gitahi, M. W. & Kabiru, E. Effectiveness of public health education on the uptake of iron and folic acid supplements among pregnant women: A stepped wedge cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open 12(9), e063615. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063615 (2022).

Caniglia, E. C. et al. Iron, folic acid, and multiple micronutrient supplementation strategies during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes in Botswana. Lancet Global Health 10(6), e850–e861. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00126-7 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Peri-conceptional folic acid supplementation and children’s physical development: A birth cohort study. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061423 (2023).

Greenberg, J. A., Bell, S. J., Guan, Y. & Yu, Y. H. Folic Acid supplementation and pregnancy: More than just neural tube defect prevention. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 4(2), 52–59 (2011).

Rahimi, S. et al. Moderate maternal folic acid supplementation ameliorates adverse embryonic and epigenetic outcomes associated with assisted reproduction in a mouse model. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England) 34(5), 851–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez036 (2019).

Fothergill, A. et al. Estimating the serum folate concentration that corresponds to the red blood cell folate concentration threshold associated with optimal neural tube defects prevention: A population-based biomarker survey in Southern India. Am. J. Clin. Nutrit. 117(5), 985–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.01.016 (2023).

Movendane, Y., Sipalo, M. G. & Chan, L. C. Z. Advances in folic acid biosensors and their significance in maternal, perinatal, and paediatric preventive medicine. Biosensors https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13100912 (2023).

Mascolo, E. & Vernì, F. Vitamin B6 and diabetes: Relationship and molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Molecular Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103669 (2020).

Kataria, N. et al. Effect of vitamin B6, B9, and B12 supplementation on homocysteine level and cardiovascular outcomes in stroke patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cureus 13(5), e14958. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14958 (2021).

Liampas, I. et al. Serum homocysteine, pyridoxine, folate, and vitamin B12 levels in migraine: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache 60(8), 1508–1534. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13892 (2020).

D’Souza, S. W. & Glazier, J. D. Homocysteine metabolism in pregnancy and developmental impacts. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 802285. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.802285 (2022).

Ogawa, S., Ota, K., Takahashi, T. & Yoshida, H. Impact of homocysteine as a preconceptional screening factor for in vitro fertilization and prevention of miscarriage with folic acid supplementation following frozen-thawed embryo transfer: A hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15173730 (2023).

Chaudhry, S. H. et al. The role of maternal homocysteine concentration in placenta-mediated complications: Findings from the Ottawa and Kingston birth cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 19(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2219-5 (2019).

Malaza, N. et al. A systematic review to compare adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with pregestational diabetes and gestational diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710846 (2022).

Liu, Y. H. et al. Study on the correlation between homocysteine-related dietary patterns and gestational diabetes mellitus: A reduced-rank regression analysis study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 306. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04656-5 (2022).

Ramakrishnan, U., Grant, F., Goldenberg, T., Zongrone, A. & Martorell, R. Effect of women’s nutrition before and during early pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes: A systematic review. Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiol. 26(Suppl 1), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01281.x (2012).

Balogun, O. O. et al. Vitamin supplementation for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016(5), CD004073. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004073.pub4 (2016).

Miallot, R., Millet, V., Galland, F. & Naquet, P. The vitamin B5/coenzyme a axis: A target for immunomodulation?. Eur. J. Immunol. 53(10), e2350435. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202350435 (2023).

Adams, J. B., Kirby, J. K., Sorensen, J. C., Pollard, E. L. & Audhya, T. Evidence based recommendations for an optimal prenatal supplement for women in the US: Vitamins and related nutrients. Maternal Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-022-00139-9 (2022).

Watson, P. E. & McDonald, B. W. The association of maternal diet and dietary supplement intake in pregnant New Zealand women with infant birthweight. Eur. J. Clin. Nutrit. 64(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.134 (2010).

Pregnancy and pantothenic acid deficiency in the guinea pig. Nutrition reviews. 1966;24(6):169–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1966.tb08408.x

Fenech, M. et al. Low intake of calcium, folate, nicotinic acid, vitamin E, retinol, beta-carotene and high intake of pantothenic acid, biotin and riboflavin are significantly associated with increased genome instability–results from a dietary intake and micronucleus index survey in South Australia. Carcinogenesis 26(5), 991–999. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgi042 (2005).

He, Y. et al. Common mental disorders and risk of spontaneous abortion or recurrent spontaneous abortion: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Affect. Disord. 354, 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.026 (2024).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Basic Application Project of Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province [2019YJ0701, and 2019YFS0416], and the Incubation Project of Mianyang Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China [2022FH005]. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization apart from those disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y., J.T. and Y.M. proposed the conceptualization and obtained funding support. B.W. and Z.L. wrote the main manuscript text. B.P. and Y.M. followed up the patients. B.W. and W.J. performed the investigation and conducted the data curation. Y.Y. graphed all figures and supplementary figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript. B.W., Z.L., and B.P. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Mianyang Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (No. S2018085, and S2018093). All participants signed informed consents.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, B., Li, Z., Peng, B. et al. Mass spectrometry of water-soluble vitamins to establish a risk model for predicting recurrent spontaneous abortion. Sci Rep 14, 20830 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71986-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71986-z