Abstract

The swelling soils, also known as expansive soils, increase in volume due to an increase in moisture content. The settlement of expansive soils could be the main reason for considerable damage to roads, highways, structures, irrigation channel covers, and the protective shell of tunnels that use bentonite for wall stability. Therefore, it is important to determine the amount of swelling pressure in expansive soils. This research uses two laboratory swelling test methods with constant volume (CVS) and ASTM-4546-96 standard, the swelling pressure of lime-stabilized bentonite soil has been estimated. Based on the key findings of this study, the swelling pressure values of pure bentonite samples tested using the ASTM-4546-96 method, compared to the constant volume swelling test, show an approximately 170% increase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pressure from soil swelling can cause complete damage to the dependent structure. This swelling occurs due to precipitation, water passing through channels, rising of the groundwater table, and absorption of this water by the soil, or as a result of irrigation of agricultural lands1. The reaction between lime and silicate, aluminate constituents of expansive soils is complex and involves cation exchange, flocculation and agglomeration, pozzolanic reaction, and carbonation. The reaction mechanisms can be classified into two groups, modification for plasticity reduction and solidification. Modification is reversible through flocculation and cation exchange activity, while solidification is irreversible through pozzolanic reaction. These reactions contribute to the treated soils' physical, chemical, mineralogical, and microstructural changes. Lime is extensively used to stabilize expansive soils worldwide, and it enhances the engineering properties of soils, such as improved strength, and higher resistance to fracture, fatigue, and permanent deformation2. With the expansion of highways and railways in modern times, the use of lime as an additive for soil stabilization has increased progressively. This is due to its cost-effectiveness and prominent stability characteristics, both in the short and long run3,4. For the first time in 1938, the United States Bureau of Reclamation identified the issue of soil swelling from a soil mechanics perspective. Since then, engineers have realized that the reasons for building damage can be something other than settling in structures. Every year, a large number of new structures are built on swelling soils. Typically, over 60% of these structures suffer minor damage such as cracking, and about 10% of these structures are severely damaged and can not be repaired anymore. Swelling soils, in terms of various swelling forces that can affect concrete projects and substructures, these issues can cause fractures and unauthorized displacements in some cases5. The pressure resulting from the swelling of these soils can destroy lightweight buildings, irrigation channel covers, flooring, etc. One of the most effective methods for improving the quality of swelling soil characteristics, which is commonly used, is the use of lime. Lime is used as an additive to modify and stabilize soils under roads and similar structures. Soil stabilization with lime involves combining and mixing lime with the optimal moisture content to form a hydroxide calcium (hydrated lime) or calcium oxide (quicklime) mixture with the soil and compacting the mixture. The process of soil stabilization with lime occurs as a result of chemical reactions between lime, soil, and water in the existing pores. Generally, lime has a good chemical reaction with most clay soils because the calcium ions in lime replace the existing ions on the surface of clay minerals. As a result, the structural properties of the soil change, reducing plasticity, reducing moisture retention capacity, reducing swelling, and increasing stability. Among the various methods available for evaluating the magnitude of swelling pressure in clay soils, the most reliable method is direct measurement by performing relevant tests. In the scientific literature on swelling soils, nominal quantities have been used with nominal similarities, which are necessary to understand the text correctly. Therefore, the following is an introduction to the quantities used in this study. Al-Rawas et al.6 investigated the effectiveness of using copper slag, granulated blast furnace slag, cement by-pass dust, and slag-cement in reducing the swelling potential and plasticity of expansive soil. Their study showed that copper slag caused a significant increase in the swelling potential of the treated samples. Other stabilizers reduced the swelling potential and plasticity to varying degrees. The study further indicated that cation exchange capacity and the amount of sodium and calcium cations are good indicators of the effectiveness of chemical stabilizers used in soil stabilization. Akcanca and Aytekin7 investigated the effect of wetting–drying cycles on the swelling behavior of lime stabilized sand–bentonite mixtures. The results of the experiments of their investigation showed that the beneficial effect of lime stabilization to control the swelling pressures was partly lost by the wetting–drying cycles. However, the test results indicated that the swelling pressures of the specimens made of sand–bentonite mixtures stabilized by lime were lower than the swelling pressures of the specimens made of only sand–bentonite mixtures. Bhuvaneshwari et al. investigated the behavior of lime treated cured expansive soil composites. Their results show that lime addition higher than the LMO brings about more permanent pozzolanic reactions which cause a tremendous increase in strength8. The time dependency of the reactions was observed through the change in PH values, conductivity, and batch test results. At the microstructural level, lime addition reduces the specific surface area and increases the pore size. The SEM results also revealed larger clusters and aggregation of the clay particles. Schanz et al.9 conducted a study on the use of lime to reduce swelling pressure in clay soil. The study involved mixing calcium bentonite with varying amounts of limestone and hydrated lime and investigating the potential swelling, swelling pressure, California Bearing Ratio (CBR), and unconfined compressive strength of the clay soil. The results of the study showed that the addition of limestone and hydrated lime to the clay soil effectively reduced its potential swelling and pressure. Furthermore, the study revealed that hydrated lime was more effective at reducing potential swelling and pressure than limestone. Kumar et al.10 carried out a study on the engineering characteristics of bentonite stabilized with lime and phosphogypsum. The research included tests on compaction, unconfined compressive strength, consistency limits, percentage swell, free swell index, California bearing ratio, and consolidation. The findings indicated that adding 8% phosphogypsum to the bentonite + 8% lime mix increased dry unit weight and optimum moisture content, percentage of swell, California bearing ratio, modulus of subgrade reaction, and secant modulus. Unconfined compressive strength increased with the addition of 8% phosphogypsum and increased curing time up to 14 days. The liquid limit and plastic limit increased, while the plasticity index remained constant. The coefficient of consolidation increased with the addition of 8% lime but remained unchanged with the addition of 8% phosphogypsum. Firoozi et al.11 investigated the effect of treatment of the soil with cement, lime, and fibers. They concluded that treatment of the soil with cement reduces the volume changes in soils but this type of treatment becomes unsuitable for soils with high plasticity index. The wetting and drying cycles in soil treated with lime will result in a loss of cohesion between the grains of soil and lime, which leads to an increase in soil volume. Thus, the method of treatment with lime is only good for places that are not exposed to the wetting and drying cycles. Pakbaz et al.12 conducted a study on the effect of adding gypsum to clayey soils that were stabilized with lime. The researchers added varying amounts of lime and gypsum to bentonite samples and then tested them for swelling pressure. The results revealed that only samples that were treated with 3% and 5% lime, and cured for seven days, showed an initial increase in swelling pressure due to the presence of gypsum. Jamsawang et al.13 conducted a study on the use of bottom ash (BTA) as a stabilizer for expansive clay. Expansive clays have a high potential for free swelling (FSP), which can lead to structural damage. Cement and lime are often used to improve swelling properties but BTA can be a more cost-effective waste management alternative. The study focused on investigating the effects of BTA on the FSP of expansive clays using the shallow mixing method. The researchers determined the optimal content of BTA and studied the effect of stabilized thickness ratio (STR) on FSP. They also analyzed mineralogical and microstructural changes and suggested a correlation between FSP and STR. The results showed that FSP values decreased when stabilized at the optimal BTA content, and a correction factor was included in the correlation to obtain an accurate prediction of field FSP values. Driss et al.14 investigated the effects of lime addition to clayey soil in Algeria, which tends to expand. The researchers added varying percentages of lime to the soil and analyzed its influence on the soil’s physical and mechanical characteristics such as consistency limits, compaction, swell, PH variation, unconfined compressive strength, as well as mineralogical and microstructural features. The results showed that adding lime increased the soil’s PH, making it more crumbly and easier to manage, while also improving its unconfined compressive strength. This was due to the flocculation of the soil structure and the production of new cementation products like CSH and CAH. Gunasekaran and Bhuvaneshwari15 using experimental and numerical quantification evaluated the swelling pressure of an expansive soil stabilized with lime and lignosulphonate as overlay cushion. The results show that as the replacement thickness of stabilized soil increases, the swell pressure decreases. Nevertheless, the lime-treated soil layer depicted lesser swell than the LS-treated soils. Analyzing the conditions for field situations in numerical analysis yielded consistent results with the laboratory inferences. Usama Khalid et al. evaluated the effectiveness of geopolymers like geopolymerized bagasse ash (GB) and geopolymerized quarry dust (GQ) in comparison to conventional fly ash-based geopolymers for improving subgrade strength. They developed a geopolymerized composite binary admixture (GBA) using GQ and GB, which showed significant improvements in structural properties16. Another method using milled wheat straw and silica fume, called composite binary admixture (CBA), was proposed to enhance soil strength and resistance to swelling (Usama Khalid et al.)17. Another study explored the use of eggshell powder (ESP) to improve fat clay soil. Incorporating 10% ESP reduced the plasticity index and liquid limit and increased unconfined compressive strength, elastic modulus, and California bearing ratio. The optimal ESP dosage was identified as 10% (Muhammad Hamza et al.)18. Finally, a novel technique utilizing geopolymerized bagasse ash (GBA), geopolymerized quarry dust (GQD), and shredded face masks (FM) showed significantly improved strength properties in treated soil, offering substantial benefits for waste disposal and recycling in the construction sector (Imad Ullah et al.)19. In previous research, a comprehensive comparison of two laboratory swelling test methods with constant volume and ASTM-4546-96 standard (ASTM Standard D4546-96)20 for estimating the swelling pressure of lime-stabilized bentonite soil has not been considered. Therefore, in this research using two laboratory swelling test methods with constant volume (CVS) and ASTM-4546-96 standard, the swelling pressure values of pure bentonite samples tested using the ASTM-4546-96 method, compared to the constant volume swelling test and results have been discussed. This research work addressed some fundamental soil improvement that is used in the civil engineering field.

Methodology

Soil swelling potential can be assessed through direct or indirect methods. Direct techniques include measuring swelling pressure or soil swelling percentage in the lab or field. These measurements are conducted using a consolidation device, and differences in testing methods arise due to factors like sample moisture, loading path, and result interpretation. The constant volume method and ASTM-4546-96 method are well-known direct approaches. In addition to direct methods, indirect methods like the constant volume swelling (CVS) test are used to evaluate swelling potential. The test involves placing the sample in a consolidation device, applying a small load, and then gradually increasing the load as the sample attempts to swell when exposed to water until the final equilibrium pressure is reached21. The new ASTM standard outlines three methods for evaluating sample swelling. All three methods involve determining the swelling pressure of the sample. The first method entails applying a small load to the sample, allowing it to freely swell, and then measuring the swelling pressure. The second method involves a similar process but under a load greater than one kilopascal. The third method requires corrections for incomplete device stiffness. This study used the first method to evaluate sample swelling pressure according to ASTM Standard D4546-96.

Materials

Bentonite

The bentonite used in this research was obtained from the Dorin Kashan Company and has a bright white color. Figure 1 shows the particle size distribution curve of the bentonite. The laboratory analyzed the technical properties of this soil according to ASTM standards and the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) is CH. Figure 2 shows The bentonite used in this research. Specifications of the used bentonite in tests have been presented in Table 1.

Lime

The purpose of producing lime is to convert its rock into a usable form. Unburnt lime, also known as quicklime or calcium oxide (CaO), is a white and moisture-absorbing substance that is obtained by heating limestone. When water is poured onto calcium oxide (unburnt lime), it hydrates and generates heat, causing some of the water to vaporize. In this process, lime absorbs water and becomes a white powder, which is called hydrated lime, dead lime, or slaked lime. The production of hydrated lime is simpler and less expensive than producing unburnt lime. Therefore, the main part of the lime production process is producing unburnt lime 22. Lime is produced in two forms: unburnt lime and hydrated lime. Unburnt lime is also called quicklime, while hydrated lime is also called slaked lime or dead lime. Unburnt lime is a strong alkaline compound that can react with all acids. On the other hand, hydrated lime is a completely stable substance that is not affected by water or most solvents. Hydrated lime and quicklime used in this study were obtained from Lorestan Industrial Lime Company in powder form (Fig. 3). The chemical analysis of these two types of lime is presented in Table 2.

Water

The presence of high levels of dissolved salts in water can affect the progress of reactions. The chemical composition of the water used for immersing a sample can impact the amount of volume change and swelling pressure. Soil with a high concentration of calcium ions swells less than soil in areas with a high concentration of sodium ions. In this study, purified water was used to eliminate the chemical effects of water on the samples.

Sample preparation

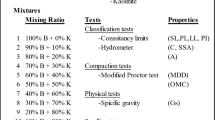

To achieve better mixing of bentonite with lime, the bentonite soil was passed through a 40-mesh sieve. The soils required for compaction were placed in a 110-degree Celsius incubator 24 h before the test then the samples were mixed according to Table 3. All percentages of added lime to bentonite in this study are based on the dry weight of bentonite, not the total weight of the mixture. For better mixing of bentonite with hydrated lime, the wet mixing method was used, while the dry mixing method was used for mixing with unburned lime. In the wet mixing method, hydrated lime was first mixed with water at a weight ratio of 1–3. The resulting slurry was then added to dry bentonite soil for mixing. After that, the required amount of additional water was added to reach the required moisture content of the bentonite-hydrated lime mixture.

When mixing dry materials, unburned lime is combined with dry bentonite soil, after which the required amount of water is added. The purpose of this is to prevent the unburned lime from slaking before it can be mixed with the soil. In both mixing methods, efforts were made to uniformly distribute moisture throughout the mixture. The tests conducted in this study can be divided into two categories, preliminary tests on the samples, including Atterberg limits, and compaction tests using the standard proctor method, as well as the swell pressure test used to evaluate the swelling pressure of the samples. From the perspective of mixing with lime, the examined samples are divided into three main groups as follows:

-

1.

Samples without lime were processed for 0 days (in-situ).

-

2.

Samples mixed with hydrated lime, including both hydrated lime with processing times of 0, 1, 7, 28, and 90 days.

-

3.

Samples mixed with unburned lime, including both unburned lime with processing times of 0, 1, 7, 28, and 90 days.

Dry mixing is performed to prevent the slaking of unburned lime before mixing with the soil. A series of laboratory tests were conducted following Table 3. Previous studies have shown that 3% lime is the optimal percentage for reducing the swelling pressure of clay soil. Therefore, 3% lime was used for mixing with bentonite. For each bentonite + 3% lime combination, two samples were prepared, and their swelling pressure was measured.

For preparing samples, after that the consolidation ring is greased, the consolidation ring is placed on the compacted sample and pressed it evenly into the sample. Using a special spatula, we carefully cut off the excess parts of the sample at the top and bottom of the ring and smooth them out. This trimming technique was used for samples processed for 0, 1, and 7 days (as the sample is soft and can be trimmed easily). Two samples of each pressed sample are prepared for the swelling pressure test. First, the first third of the pressed sample is used for a 50 mm diameter ring, followed by the remaining two-thirds for a 75 mm ring),. To account for possible variations in moisture content during the crushing and smoothing of the sample in the consolidation ring, a portion of the compressed sample is set aside in a container before this process to control the moisture content. This part is then weighed and stored in a controlled environment. A comparison of the moisture content before and after crushing (when the sample is ready for the consolidation machine) showed that all samples had a difference in moisture content of less than one percent, which is considered insignificant in geotechnical considerations.

Given the hardness of the samples, a hydraulic jack was used to remove the samples for testing after 28 and 90 days of curing.

The main focus was on the swelling pressure test, in which the volume (height) of the sample inside the ring increases during swelling. To ensure that the sample has sufficient space to expand, the height of the sample was set approximately five millimeters lower than the height of the rim. To achieve this, a pressed plastic plate was precisely cut to create a cylindrical protrusion that corresponded to the diameter of the ring and had a height of five millimeters.

Devices

In this study, a variety of laboratory equipment was used to process different soils and perform the primary tests as described in this section.

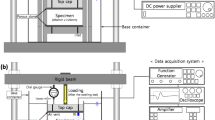

This device is a conventional consolidation device. Due to the large number of samples, two consolidation devices were used to consolidate the ring diameter of the cell. One had a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 20 mm, while the other had a diameter of 75 mm and a height of 20 million meters. All components of this device comply with international standards. The strain gauge had a maximum deflection of 20 mm and an accuracy of 0.002 mm.

Calibration of the consolidation device

ASTM standards D-2435-96 for the consolidation test and D-4546-96 for the swelling test recommend determining the deformation of the oedometer caused by the load before performing the tests. During the consolidation and swell tests, the soil sample changes shape, and part of the change in height is due to the device's deformation. To accurately measure the height changes of the soil body, these device-induced changes should be accounted for by adding or subtracting them from the values observed during the test. To achieve this, the ASTM standard suggests placing a metal cylinder with a slightly smaller diameter than the rim and a similar height inside the oedometer instead of the soil sample. In this way, you can follow the changes in the shape of the device during the loading and unloading phases and simulate all aspects of the main test, including the presence of filter papers at the top and bottom of the sample. This procedure was followed in the series of tests performed. As the results varied in each series, the numerical average was used. Subsequently, the device-induced deformation values were subtracted from the observed values in the calculations to determine the actual deformation of the soil sample. Therefore, it was assumed that the actual settlement values during swelling were back to the initial level. For example, if the sample settles by M units under load and the error of the device is N units according to the calibration, the actual settlement is (M–N) units, so the sample must be inflated by (M)–(N) units until the next load to reach the initial height in the constant volume swell test. This adjustment was made in all phases of the constant volume swell test.

Results and discussion

Two below methods were investigated for estimating the swelling pressure of lime-stabilized bentonite soil.

-

1.

Constant volume swelling method.

-

2.

ASTM Standard D4546-96 method.

Constant volume swelling method (CVS)

In this compaction method, a small initial load of around 5 kPa is applied to the soil sample. After compaction, the sample is immediately exposed to water to allow for swelling. The sample continues to swell until it returns to its initial volume or height. At this point, the next load (also around 5 kPa) is applied. This process is repeated until the sample can withstand all the applied loads, and the final load applied to the sample is referred to as swelling pressure. visually explains the entire swelling process. In this test, all samples were subjected to uniform loading steps of approximately 5 kPa.

ASTM Standard D4546-96 method

Soil sampling was conducted, and the sample was placed into a compaction device. A load of 2 kPa was applied to the device, and water was added. The sample was then allowed to freely swell, and readings were taken every 30 s for a period of up to 24 hours. For some samples, readings were taken for up to 48 hours. The swelling pressure of the soil samples was determined by loading the sample after complete swelling until it reached its initial height. An odometer device was used to estimate the swelling pressure of the soil samples for both test methods. The samples were prepared with aging periods of 0, 1, 7, and 28 days. Two identical samples were prepared for all combinations, and their swelling pressure was determined. Finally, the mean of the two samples was calculated.

Test results

Atterberg limits

The results of tests conducted on soil samples including the liquid limit, plastic limit, plasticity index, and plasticity chart are presented in Table 4. The analysis shows that the soil belongs to the CH group based on the plasticity chart and the particle size distribution curve of the samples, as per the Unified Soil Classification System. It is worth noting that all samples exhibit a high swelling potential according to the Atterberg limit test results. Additionally, the liquid limit of samples treated with hydrated lime increased due to the lime’s high moisture absorption, while the liquid limit decreased in samples treated with quicklime because of the increased calcium cation concentration near clay particles. Furthermore, the plastic limit of all samples treated with different types of lime increased compared to the base soil. In the short term, cation exchange reactions between soil particles and lime change the soil structure to a flocculated state, making it plastic at high moisture content. The soil’s cracking moisture content (plastic limit) increases for samples treated with lime due to the lower percentage of clay particles compared to pure bentonite. Lastly, the plasticity index of all samples treated with different types of lime increased compared to the base soil due to the absorption of calcium ions by clay particles and the establishment of a relative balance between negative and positive charges, which reduces the tendency of clay particles to absorb water molecules.

Compaction tests

Based on previous studies, researchers have found that a mixture of 3% lime and bentonite reduces the swelling pressure of clay soil. The samples were tested using consolidation rings and a hydraulic jack. Two rings with diameters of 5 cm and 7.5 cm were used in the study. According to the compaction test, all samples stabilized with different types of lime had a lower maximum dry density (MDD) and were inclined towards the right (higher moisture content) compared to the base soil. Thus, the maximum dry density of samples stabilized with lime decreased, and their optimal moisture content increased. Lime and clay soil react quickly, changing the soil structure and reducing the maximum dry density. Lime is also essentially lighter than soil and reduces the maximum dry density. Adding lime to soil increases soil porosity and void ratio, which reduces the maximum dry density. Furthermore, adding lime increases the moisture content of the samples due to the absorption of moisture to create cation exchange and pozzolanic reactions between lime and clay soil. In addition, the compaction curves of bentonite samples stabilized with quicklime were located at lower positions (reduced maximum dry density) and on the right side (increased moisture content) compared to those stabilized with hydrated lime. The increase in optimal moisture content in samples stabilized with quicklime is due to the hydration of CaO (calcium oxide) during pozzolanic reactions, which consume a certain amount of water (Table 5).

According to Fig. 4, the compaction curves of lime-stabilized samples show lower dry density and higher moisture content compared to the base soil. This indicates a decrease in maximum dry density and an increase in optimum moisture content in the lime-stabilized samples. The quick reaction between lime and clay alters the soil structure, resulting in reduced dry weight. Lime, being lighter than soil, decreases the specific dry weight. Additionally, lime enhances soil porosity, further reducing the dry weight. The incorporation of lime raises the moisture content by absorbing moisture and facilitating cationic and pozzolanic exchange reactions with clay23,24,25. The density curves of bentonite samples treated with quicklime show lower dry weight and increased moisture content compared to samples treated with hydrated lime, as shown in Fig. 4. This is due to the hydration of CaO during pozzolanic reactions, resulting in water consumption and achieving optimum moisture content (Table 5).

The swelling pressure

Several pure bentonite samples (3 per method) were prepared to evaluate the swelling pressure and compare the results of the constant volume and ASTM-4546-96 methods. The average swelling pressure of pure bentonite according to ASTM-4546-96 and the constant volume method was tested. Figure 5 shows the percentage of free swelling of pure bentonite over time in logarithmic form. Figure 6 illustrates the average swelling pressure according to the constant volume method (approx. 339 kPa), while Fig. 7 shows the average swelling pressure according to the ASTM 96–4546 method (approx. 569 kPa at a consolidation percentage of zero). It is noticeable that the swelling pressure of pure bentonite according to the ASTM 4546–96 method exceeds that of the constant volume method.

Swelling pressure of bentonite mixed with quick and hydrated lime

The values of swelling percentage and swelling pressure for bentonite samples stabilized with hydrated lime and quick-lime at processing times of 0, 1, 7, and 28, according to the ASTM-4546-96 test, are presented in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. Additionally, Table 6 summarizes the swelling pressure values for these samples based on the ASTM-4546-96 test and the constant volume swelling test (CVS).

The swelling pressure values of pure bentonite samples tested using the ASTM-4546-96 method, compared to the constant volume swelling test, show an approximately 170% increase. Additionally, the swelling of soil with a 3% combination of hydrated lime and quicklime after 0, 1, 7, and 28 days of processing is presented in Table 6, based on both the ASTM-4546-96 (ASTM Standard D4546-96) method and the constant volume swelling test.

The results indicate an average increase of approximately 180% in the swelling pressure values obtained from the ASTM method compared to the constant volume test across all processing time intervals (0, 1, 7, and 28 days). The swelling pressure values for bentonite samples stabilized with 3% hydrated lime and quicklime, as determined by the ASTM and constant volume swelling tests, show an average increase of 178% and 181%, respectively, over the processing times of 0, 1, 7, and 28 days. In Figs. 10 and 11, the declining swelling pressure trend of bentonite mixed with 3% hydrated and quick lime is depicted in two ASTM methods and constant volume. The ASTM method exhibits significantly higher swelling pressure compared to the constant volume method, with the greatest reduction rate observed during the processing period from composition to the seventh day. Figure 12 depicts the swelling pressure ratio according to the ASTM and constant volume methods as a percentage. The mentioned ratio for the bentonite and quicklime mixture shifts from 150% initially to 161% by day 28. Likewise, the ratio for hydrated lime rises from 166% at the start of the test to 182% after 28 days.

Conclusions

The study evaluated soil swelling pressure using the CVS and ASTM-4546-96 methods on pure bentonite samples and those mixed with 3% hydrated lime and 3% quicklime, at a moisture content slightly below optimal levels, over 0, 1, 7, and 28-day periods. Key conclusions drawn from the conducted tests are as follows:

-

1.

The evaluation in this study found that the liquid limit increased in samples stabilized with hydrated lime but decreased in those stabilized with quick lime. The plastic limit and plasticity index increased in all lime-stabilized samples compared to the base soil, highlighting lime's positive effect on reducing plasticity and enhancing the workability, strength, and durability of the stabilized soil.

-

2.

Soil sample tests showed that a 3% lime and bentonite mix was used to measure swelling pressure. Samples stabilized with lime had lower maximum dry density and higher moisture content than base soil, indicating decreased density and increased optimal moisture content in lime-stabilized samples.

-

3.

Assessments in this study found that adding lime to the soil altered its structure by reducing maximum dry density and increasing soil porosity and void ratio. This also raised moisture content in the samples through moisture absorption to facilitate cation exchange and pozzolanic reactions between lime and clay soil.

-

4.

Pure bentonite samples tested using ASTM-4546-96 show a 170% increase in swelling pressure compared to the constant volume swelling test.

-

5.

The swelling pressure of bentonite samples treated with 3% hydrated lime and quicklime increased by an average of 178% and 181%, respectively, over 0, 1, 7, and 28 days, based on ASTM and constant volume swelling tests.

-

6.

The results show a 180% average increase in swelling pressure values using the ASTM method compared to the constant volume test at various time intervals (0, 1, 7, and 28 days).

It should be noted that future research could explore long-term swelling behavior, analyze lime content variation effects, and compare soil stabilization techniques to better understand and manage swelling soil challenges.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Fredlund, D. G. Geotechnical problems associated with swelling clays. In Developments in Soil Science, vol. 24 (eds. Ahmad, N. & Mermut, A.) 499–524 (Elsevier, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2481(96)80016-X.

Barman, D. & Kumar Dash, S. Stabilization of expansive soils using chemical additives: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14(4), 1319–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2022.02.011 (2022).

Rogers, C. D. F. & Glendinning, S. Lime requirement for stabilization. Transp. Res. Rec. 1721(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.3141/1721-02 (2000).

Raja, P. S. K. & Thyagaraj, T. Sulfate effects on sulfate-resistant cement–treated expansive soil. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 79, 2367–2380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01714-9 (2020).

Holtz, W. G. & Hart, S. S. Home construction on shrinking and swelling soils. Virginia, United States: National Science Foundation. Civ. Eng. ASCE 43(8), 49–51 (1978).

Al-Rawas, A. A., Taha, R., Nelson, J. D., Al-Shab, B. T. & Al-Siyabi, H. A comparative evaluation of various additives used in the stabilization of expansive soils. Geotech. Test. J. 25(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ11363J (2002).

Akcanca, F. & Aytekin, M. Effect of wetting–drying cycles on swelling behavior of lime stabilized sand–bentonite mixtures. Environ. Earth Sci. 66, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1207-5 (2012).

Bhuvaneshwari, S., Robinson, R. G. & Gandhi, S. R. Behaviour of lime treated cured expansive soil composites. Indian Geotech. J. 44, 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40098-013-0081-3 (2014).

Schanz, T. & Elsawy, M. B. D. Swelling characteristics and shear strength of highly expansive clay–lime mixtures: A comparative study. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 7919–7927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-014-1703-5 (2015).

Kumar, S., Dutta, R. K. & Mohanty, B. Engineering properties of bentonite stabilized with lime and phosphogypsum. Slovak J. Civ. Eng. 22(4), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjce-2014-0021 (2015).

Firoozi, A. A. & Olgun, C. G. Fundamentals of soil stabilization. Geo-Engineering 8, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-017-0064-9 (2017).

Pakbaz, M. S. Evaluation of time rate of swelling pressure development due to the presence of sulfate in clayey soils stabilized with lime. Int. J. Geomate 12(32), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.21660/2017.32.76370 (2017).

Jamsawang, P. et al. The free swell potential of expansive clays stabilized with the shallow bottom ash mixing method. Eng. Geol. 315, 107027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107027 (2023).

Driss, A. A., Khelifa, H. & Ghrici, M. Effect of lime on the stabilization of an expansive clay soil in Algeria. J. Geomech. Geoeng. 1(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.38208/jgg.v1i1.413 (2023).

Landlin, G. & Bhuvaneshwari, S. Evaluation of swelling pressure of an expansive soil stabilized with lime and lignosulphonate as overlay cushion: An experimental and numerical quantification. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 122087–122106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30448-1 (2023).

Khalid, U., Rehman, Z. U., Ullah, I., Khan, K. & Kayani, W. I. Efficacy of geopolymerization for integrated bagasse ash and quarry dust in comparison to fly ash as an admixture: A comparative study. J. Eng. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jer.2023.08.010 (2023).

Khalid, U. et al. Integrating wheat straw and silica fume as a balanced mechanical ameliorator for expansive soil: A novel agri-industrial waste solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 73570–73589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27538-5 (2023).

Hamza, M. et al. Utilization of eggshell food waste to mitigate geotechnical vulnerabilities of fat clay: A micro–macro-investigation. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-10921-3 (2023).

Ullah, I. et al. Integrated recycling of geopolymerized quarry dust and bagasse ash with facemasks for the balanced amelioration of the fat clay: A multi-waste solution. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-11219-0 (2023).

ASTM International. Standard test method for one-dimensional swell or settlement of cohesive soils (Designation D 4546-96). ASTM International. https://www.astm.org/d4546-96.html (1996).

Fakher, A. Identification and Classification of Swelling Soils (Master’s thesis). University of Tehran (1994).

Offer, Z. & Blight, G. E. Measurement of swelling pressure in the laboratory and in situ. Transport. Res. Record 1983, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3141/1032-01 (1983).

Ali, J. S. M. Stabilization of organic soil using un-alaked lime. In 4th International Conference on Civil Engineering 326–333. Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran (1997).

Rajasekaran, G. Sulphate attack and ettringite formation in the lime and cement stabilized marine clays. Ocean Eng. 32(5–6), 1133–1159 (2005).

Kumar, A., Walia, B. S. & Bajaj, A. Influence of fly ash, lime, and polyester fibers on compaction and strength properties of expansive soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 19(3), 242–248 (2007).

Funding

No type of funding has been used to support this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahdi Maleki, Rasool Sadeghian, and Adel Kazempour wrote the main manuscript text and they prepared figures and tables. Mahdi Maleki reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadeghian, R., Maleki, M. & Kazempour, A. Laboratory investigation of the swelling pressure of bentonite with quicklime and hydrated lime using ASTM-4546-96 and constant volume methods. Sci Rep 14, 21223 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72143-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72143-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A Three-Dimensional Geospatial Modelling of Soil Engineering Properties for Coastal Infrastructure Planning: the Case Study from Bengkulu, Indonesia

Transportation Infrastructure Geotechnology (2026)

-

A New Approach for the Solution of One-Dimensional Consolidation Equation in Saturated Soils Under Various Time-Varying Loads

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation: A Critical Review on a Sustainable Method for Improving Expansive Soil in the Era of Climate Change

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Correlations Among CPT, MPT, and SPT in Clayey Soils: A Case Study from Central Northern Algeria

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)

-

Rheological Behaviour and Model of Typical Metal Tailing Slurries Considering the Effect of Particle Concentration

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)