Abstract

Shape bias, the tendency to link the meaning of words to the shape of objects, is a widely investigated phenomenon, but the extent to which it is linked to vocabulary acquisition and/or to tool using is controversial. Understanding how non-human animals generalize the properties of objects can provide insights into the evolutionary processes and cognitive mechanisms that influence this bias. We investigated object generalization in dogs, focusing on their tendency to attend to shape or texture in a two-way choice task. We analyzed data of thirty-five dogs that were successfully trained to discriminate a target object among distractors and retrieve it to their owner. In subsequent testing, dogs chose between objects similar to the target in either shape or texture. Results showed that dogs first approached objects of similar shape, but then predominantly chose objects of similar texture. This suggests a reliance on visual cues for initial assessment and tactile cues for final discrimination. Our findings highlight the influence of perceptual modalities on object generalization in dogs, showing that, before object manipulation, they seem to show a shape bias but, once they make physical contact with the objects, they rather rely on texture to generalize. This study contributes to our understanding of generalization in a non-verbal and non-tool using species and opens avenues for comparative investigations into the relationship between vocabulary acquisition, tool using and biases in object generalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human infants tend to link the meaning of words to the shape of objects, rather than to other features (e.g.,1). In a seminal study on shape bias, Landau et al. (1988)2 showed that when two- and three-year-old children or adults learn to connect a new object name with a new object, they generalize the meaning of the new name to objects that are similar in shape, but not to objects that are similar in size or texture.

While shape bias has since then been widely investigated, its link with vocabulary learning is not fully understood and some results seem to point to the lack of a relationship between shape bias and vocabulary size or composition (e.g.3). Infants’ attention to shape is not necessarily specific to lexical contexts and is present at the early stages of productive language development4. For example, using an imitation paradigm that did not involve labeling the objects, Graham and Diesendruck (2010)4 found that 14–15-month-old infants generalize nonobvious properties preferentially across objects that are similar in shape, rather than across objects that are similar in other physical dimensions. Children’s shape-based inferences, however, correlated with both age and vocabulary size. Thus, it is possible that experience in vocabulary learning may tune children into attending more to shape5. It has been suggested that, as infants acquire a more sophisticated understanding of object kinds, they become more attuned to the cues related to object kinds, specifically, their shape similarity and common labels4. Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith (2004)6 also reported positive correlations between vocabulary measures and a shape bias in name extension tasks. In addition, it seems that 2- to 3-year-old “late-talkers” (i.e., children who do not readily acquire vocabulary) do not show a shape bias comparable to typically developing children; rather, many of them tend to extend novel names to objects of similar texture7. While some authors (e.g.8) found attentional biases to shape in 6- to 12-month-old infants, it is suggested that the shape bias is not reliable until 2.5 years old and its strength increases with age9.

Studies on non-linguistic animal models may help shed light on whether some language-related skills are necessary for shape bias to emerge. Supporting the lack of a necessary link between language learning and shape bias, preferential attention to shape has also been found in the context of tool using in non-human primates (e.g., cotton-top tamarins and rhesus macaques10; cotton-top tamarins11). It is possible that this bias towards preferentially attending to the shape of objects evolved in tool users because shape is a key component affecting tool functionality. Thus, testing shape bias in tool users and non-tool users may help shedding light on this hypothesis.

Dogs evolved and develop in the human environment, and, for these reasons, this species is growingly accepted as a valid model for studying social cognition (e.g.,12,13). Dogs readily learn to discriminate trained objects (e.g.,14) and cooperate with humans in various tasks, some of which also involve object discrimination (for example, in the case of dogs trained for assistance). Studying how dogs generalize the properties of objects can provide information on generalization preferences in a non-linguistic and non-tool-using species, thereby contributing to shedding light on the presence (or lack) of links between vocabulary learning, tool using and the tendency to attend to shape.

Recently, some rare individual dogs with a capacity to rapidly acquire a vast receptive vocabulary of object names were identified15,16. One of these dogs was found to spontaneously extend familiar words referring to objects to novel items of the same shape, without being specifically trained to do so17. This dog’s categorization accuracy was higher when, in addition to information on the objects’ shape, she received experience about the objects’ affordances. However, in this study the features of the familiar and tested items (texture, color, shape, etc.) were not systematically manipulated. Thus, it is not known whether the dog would have also (or preferentially) categorized new items based on other properties, such as texture or size.

Van der Zee et al. (2012)18 applied a paradigm similar to the one used by Landau et al. (1988)2 to test shape bias in a single dog with a large receptive vocabulary. In this case the dog was trained and tested by experimentally manipulating the shape, size, and texture of the trained and test items. The study showed that the dog generalized a trained object to objects of similar size—but not of similar shape or texture—after a short 10-min period of training, and to objects of similar texture after a more extended period of training (39 days). The reason for different preferences resulting from a short or a long period of training is not known. Since this dog had acquired, prior to the study, a vocabulary of 43 object names, he should be considered one of the rare Gifted Word Learner dogs15. Thus, it is not known how typical dogs that lack vocabulary acquisition capacities would generalize the properties of a trained object.

Ecological differences in relying on perceptual modalities may affect how objects are generalized in different species. Humans primarily rely on vision for object identification. Thus, visual object shape may be the most salient feature for identifying objects (e.g.,19). Dogs too seem to primarily rely on vision in object discrimination tasks, although they can promptly and successfully revert to using other modalities when vision is not possible—e.g., in the dark14. It is possible that the dog tested by Van der Zee et al. (2012)18 tended to rely on size and texture because the trained task involved carrying the objects in his mouth and these cues were more salient for manipulating the objects with the mouth (bite size and felt texture).

To study object generalization in dogs, we first trained dogs to discriminate an object among distractors. Then we tested whether the dogs chose objects that were similar to the target either in shape or texture in a two-way choice task. In addition to analyzing which feature of the objects (shape or texture) dogs relied on, upon choosing which object to fetch to their owners, we also analyzed which object they approached first, assuming that this indicates how they solve the problem when seeing the objects, before having the possibility to manipulate the objects with their mouth (see also14 for evidence that approach from afar may indicate use of vision in dogs). Based on the results of the study by Van der Zee et al. (2012)18, we expected dogs to generalize the trained item to objects of similar texture. However, since dogs tend to rely on vision to solve discrimination tasks14, we expected them to first approach object of similar shape, as shape is likely a more salient visual feature than texture.

Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and adhere to the ARRIVE guidelines. Ethical permission for conducting this study was obtained from The Institutional Committee of Eötvös Loránd University (N. PE/EA/691-5/2019). All owners gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Subjects

56 adult dogs (mean age = 69.1 ± 42.5 months old), whose owners reported being motivated to fetch toys, participated in the study. All the dogs lived with their owners as family dogs. The dogs belonged to various breeds (25 Border collies, 3 miniature American shepherds, 4 Australian shepherds, 1 German shepherd, 2 Australian Kelpies, 6 Golden and Labrador retrievers, 1 Lagotto Romagnolo, 9 mixed breed, 1 Mudi, 1 Novia Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, 1 Pumi, 1 Shiba Inu, 1 Vizsla). Additional information about each subject is available in Table S1 in the Supplementary material.

Material

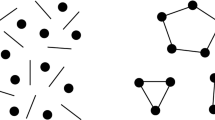

All objects used in the testing phase were crafted with foam, to create three different shapes with dimensions that kept volume constant across all objects (720 cm3). Objects of each shape were covered with different materials, to obtain objects of three different textures: velcro, duct tape and uncovered foam (Fig. 1). All the objects were painted with the same non-toxic black spray color. We varied both shape and texture as much as possible for both features, while maintaining the other variables constant (e.g., volume, colour, weight).

Dimensions of each object shape are reported in Table 1.

Setup

Two adjacent rooms were used for the experiment. The owner and the dog were asked to stay in one room (Owner room), while the objects to be retrieved were in the adjacent room (Object room). This was done to prevent the owner from giving inadvertent visual cues to guide the dog’s choices to one or the other objects.

Procedure

The experiment comprised a training phase, during which the dogs were trained to discriminate a target object among distractors and bring it to their owner, followed by a testing phase. In this last phase, the dogs were presented with 4 generalization trials in which the target was absent, and they could choose between fetching two objects, one identical to the target in shape and the other identical to the target in texture. To keep the dogs focused and motivated for the task of fetching the target, these trials were interspersed with 4 trials in which one of the two objects was identical to the target in all characteristics, and the other was identical either in shape or in texture (target trials).

To control for odour cues, all objects were stored together and, additionally the owner and the experimenters touched all the objects with their hands before the experiment started.

Training phase

The training phase took place in the object room, immediately before the test phase. The training was aimed at teaching dogs to choose and retrieve to the owner one of the objects described above (target object), when this was among distractors that differed from it in all features (shape, texture, size, colour etc.). Each dog was randomly assigned one of the objects described above (Fig. 1) as a target object. The owners were instructed to name the target object “Dax” both during the training and during the test. The training was considered successful, and the test started, when the dog was able to discriminate and retrieve the target object, among the distractors, in five consecutive trials in which all objects were out of view from the owner (i.e., the owner could not provide visual cues to guide the dog’s choices to the target). A detailed description of the training and the distractors used in this phase (Figure S1) is provided in the supplementary material.

Testing phase

The test phase consisted of eight trials in which the dog had to choose between two objects placed on the floor. Out of these eight trials, four were target trials (see below) and four were generalization trials.

Target trials: the dog had to choose between the target object and an object of either the same shape or the same texture as the target.

Generalization trials: the dog had to choose between an object of the same shape, but different texture, than the target and an object of the same texture but different shape than the target.

The two types of trials were alternated, starting with a target trial.

Before each trial started, the experimenters placed the two objects on the floor in the Object room. The objects used in each trial, and their respective positions were semi-randomly determined according to the schedule reported in Supplementary Table S2, Figure S2 and S3 in Supplementary material.

The objects’ placement was done by the experimenter out of view for the dog and owner, while they stayed out of sight in the adjacent Owner room. Then the owner was asked to send his dog to retrieve the target object from the Object room, as in the last trials of the training phase.

We considered the dog to make a choice for one of the objects when he returned to the owner while holding an object in his mouth. If the dog did not pick up any object in 40 s or crossed the doorway without any object in his mouth, the dog’s choice was scored as “no choice” and the next trial started. Whenever the dog selected and returned an object to his owner, irrespective of what similarity this object shared with the trained target, the owner praised him and played with him with a copy of the target toy (in case the dog selected another object, the experimenter handed to the owner a target object to play with). The owner was asked to stay neutral if the dog did not select anything.

To control for odour cues, after each trial, the object that the dog picked up with his mouth was replaced by an identical one that the dog had not touched.

Behavioural variables

We analyzed the following variables:

First contact: The dogs were considered to make first contact when touching an object with their nose, muzzle, or front paw for the first time upon entering the objects’ room.

Object choice: The dogs were considered to have chosen an object when they took it to the owner room (i.e., the dogs’ shoulders crossed the doorway while holding an object in their mouth). In the target trials, dogs could choose the target or the other object. In the generalization trials, dogs could choose an object of the same shape or of the same texture as the target. The choice was coded as “no choice” when the dogs came back to the owner room with nothing in their mouth or if they stayed in the objects room for the trial duration (40 s) without going back to the owner. Note that the dogs could bring to the owner the same object they had first touched or could touch an object but then bring to the owner the other one.

Side choice: To assess whether dogs presented a side bias, we coded the side where the object retrieved by the dog was located (Right or Left).

Statistical analysis

Among the 56 dogs that were recruited for the study, 13 dogs were excluded because they did not successfully complete the training phase. Three other dogs were excluded from the analysis because they retrieved fewer than 2 items over the 8 trials during the test. Dogs that presented a side bias (N = 2) were excluded from analysis (Dogs were considered to present a side bias when they consistently chose an object on the same side in 7 out of 8 trials, while choosing the target object only two times or less in target trials). In addition, 3 dogs were included only in the analysis regarding success in choosing the target in target trials, but were excluded from further analysis, because they never chose the target over the 4 target trials.

Thus, further statistical analysis was carried out on N = 35 dogs (age mean = 71.06 ± 42.07 months old; breeds: 17 Border collies, 9 shepherds, 4 retrievers, 5 mixed breeds).

The analyses were conducted separately for the target and generalization trials. All analyses used RStudio 2023.06.1 524. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to:

-

Compare the frequency of approaching and choosing (i.e., retrieving) the same object (as opposed to first touching one object and then choosing the other one) between target trials and generalization trials;

-

Compare the frequency of first contact with the object of the same shape to the frequency of first contact with the object of the same texture as the target in generalization trials;

-

Compare the frequency of choosing objects of the same shape as the target to the frequency of choosing objects of the same texture as the target in generalization trials;

-

Compare the No choice frequency between target trials and generalization trials.

-

Binomial tests were used to compare to chance level the frequency of choosing the target in target trials. As there were four target trials in total, chance level was set at 2 trials over 4. Estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

First contact

Dogs touched an object and then retrieved it to the owner (i.e., they retrieved to the owner the same object with which they made initial contact) more often in target trials compared to generalization trials (Fisher Exact Test, p = 0.005, N = 35).

In generalization trials, dogs made first contact more frequently with objects of the same shape as the target than with objects of the same texture. (Fisher Exact Test p < 0.001, N = 35; Figs. 2 and 3).

Boxplots representing the Maximum, Minimum, First Quartile, Median, Third Quartile and outliers of the frequency of First contact with the object of, respectively, same shape or same texture as the target, in the four generalization trials (A); Boxplots representing the Maximum, Minimum, First Quartile, Median, Third Quartile and outliers of the frequency of choices of the object of, respectively, same shape or same texture as the target, in the four generalization trials (B). Each dot represents one dog.

(A) Percentage (mean ± SE) of trials in which dogs made first contact with the different available objects in the four target trials and in the four generalization trials. (B) Percentage (mean ± SE) of trials in which dogs chose the different available objects in the four target trials and in the four generalization trials. * indicates significant differences (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

Choices in target trials

Overall, dogs retrieved the target in 67.1% of the trials CI 95% = [56.8–76.1], significantly above chance (Binomial test, p < 0.001, Fig. 3; Table 2).

Choices in generalization trials

Overall, dogs chose an object of the same texture as the target significantly more often than objects of the same shape (Fisher Exact Test, p < 0.001, N = 35; Fig. 3; Table 3).

No choices

Dogs made significantly more no choices in generalization trials than in target trials (Fisher Exact Test, p = 0.017, N = 35; Fig. 3).

Figure 4 presents a summary of the results, reporting the percentage of first contact and choices for the different shape and texture objects.

Summary of the results reporting the percentage of first contact and choices of the dogs in the four target trials and in four generalization trials. Yellow arrows refer to the choices of the dogs that approached first the target object; Blue arrows refer to the choices of the dogs that approached first the same shape object; Red arrows refer to the choices of the dogs that approached first the same texture object; Grey arrows are refer to the choices of the dogs that made no choices.

Discussion

This study provides insights into how dogs generalize properties of objects, focusing on their tendency to attend to shape or texture in a two-way choice task. Specifically, our results show that dogs tend to first approach objects of similar shape and, only after having touched them, thus probably perceiving that their texture differs from the trained target object, they switch to choosing an item of similar texture. Thus, dogs may show a shape bias that is reminiscent of that observed in human children only when using the visual modality, but not when all senses can be deployed to solve the task. When dogs use all senses, they rather show a texture bias. This highlights the potential influence of perceptual modalities, and the importance of the task employed in generalization studies—specifically whether it is a visual task or it involves making physical contact with the objects.

In target trials, dogs showed a significant preference for choosing the target object over objects similar to it in either shape or texture, showing that the training was generalized to a situation that included non-trained distractors that are similar to some extent to the target. The dogs’ preference for the target also corroborates previous findings showing that dogs readily develop a preference for a trained object, discriminating it based on its physical properties (e.g.,14). Our methods do not allow to assess whether the dogs had learned the object name, however it is unlikely that they did, since previous studies showed that typical dogs do not appear to learn object names, even after extensive training15. The dogs’ preference for the target seems to contrast the results of van der Zee et al. (2012)18. The Gifted Word Learner dog tested by Van der Zee et al. (2012)18 did not show a preference for the target object over other objects similar to it in shape, texture or size, despite being able to recognize the trained object by name, among his other named familiar toys. This may potentially suggest that Gifted Word Learner Dogs have a greater tendency to generalize than typical dogs and/or may form mental categories of named objects which include objects similar in shape (see17) and, potentially, in other features. However, this hypothesis would need to be tested with a larger Gifted Word Learner dogs sample size. It should also be noted that the present study and the one by Van der Zee et al. (2012)18 differ in several aspects, besides recruiting typical dogs or a Gifted Word Learner dog: in contrast to Van der Zee et al. (2012)18, we did not test objects of different sizes; additionally, the objects used by Van der zee et al. (2012)18 mostly varied in their shape only along two dimensions whereas we varied the shape along all dimensions. For these reasons, direct comparisons between these two studies should be avoided.

The higher frequency of no choices in the generalization trials, compared to the trials when the target object was present, may indicate some limits in dogs’ tendency to generalize and suggest that dogs, in some cases, may not have recognized similarities between the target object and the items of similar shape or similar texture. Moreover, dogs chose an object directly, without first approaching the other object, more often in target trials compared to generalization trials. This may also corroborate that generalization trials were more challenging for the dogs, requiring them to explore both alternatives. Several factors, such as previous training and playing experience, may have influenced the dogs’ tendency to generalize this task.

The main results of this study are best illustrated by the combination of the results of the dogs’ first contact and choices in the generalization trials. These findings suggest that dogs’ generalization tendencies are influenced by perceptual modalities. It is reasonable to assume that, when using visual modalities, shape may be a more salient feature to discriminate objects than texture as shape information is likely more visually conspicuous across objects than texture. Thus, dogs’ tendency to first approach objects of the same shape as the target suggests reliance on visual cues when initially assessing objects from afar. Previous research also suggested that dogs primarily rely on vision for object identification in discrimination tasks, although they can adaptively use other modalities when necessary (e.g.,14,20,21).

Dogs then were more likely to choose (i.e., fetch to the owner) objects of the same texture as the target, rather than objects of the same shape. This preference may reflect the salience of texture in object discrimination tasks, when the task involves object manipulation, because texture provides salient tactile and sensory cues that dogs can readily perceive and differentiate.

In humans, there is a clear priority of vision over other modalities for object identification (e.g.,19). However, touch has a clear developmental precedence over vision and, despite its potential role as a sensory scaffold on which multisensory perceptual development is constructed, the role of touch in perceptual development has not received much attention from researchers22.

To our knowledge, our results provide the first evidence that dogs may also use tactile information to solve this type of object discrimination task. It is also possible that dogs used a combination of tactile and olfactory information. Despite controlling for the odor of the owner, of the experimenter and of the dogs’ saliva, the different materials with which the objects were covered may also differ in odor. However, olfaction may not be the main or the only sense used in this type of tasks. Previous research found that, when dogs were administered a discrimination task in the dark, the amount of time spent sniffing was less than 20% of their searching time14.

Our results highlight that biases to attend to different features of objects are influenced by several factors, including perceptual modalities, so that the behavioural measure taken as evidence of a bias (i.e., looking at the object VS touching/picking it up) may heavily influence the outcome. Considering that shape bias is most often studied employing looking paradigms, in which, by definition, only visual modalities are considered (e.g.,23 for review), the results of our study appear of particular interest to guide and inform future research in different species. Most likely, if we would have used only a looking paradigm or if we would have only analyzed which object the dogs approached, we would have concluded that dogs show a shape bias.

It is not possible to mathematically calculate and compare the degree of variation of the objects in texture to the degree of variation in shape. Thus, we cannot completely rule out that, in the generalization trials, instead of accomplishing the trained task of fetching the target (or what they perceived as most similar to it), dogs were preferring objects perceived as more different (therefore, also more novel) and avoiding similar ones. However, we think this is unlikely because then dogs would have not shown a preference for shape in their first approach (as similarity in shape was visually more salient than similarity in texture) but would have rather immediately approached the item visually perceived as more different. Moreover, since we systematically varied each of the two features as much as possible, while maintaining all other features constant (volume, colour, weight etc.), we think it is unlikely that the objects used in generalization trials appeared as novel for the dogs, such that they would have elicited a novelty preference.

Human infants seem to form shape representations based on the skeletal structure of the shape8. Dogs tested on their global/local preferences in discrimination tasks showed a global bias24. However, in a subsequent study, the learning requirements of the task affected the tendency to focus on global aspects of the stimuli25. Thus, we cannot conclude with certainty that dogs relied on global information in the present study.

We notice that similar biases in different species may not necessarily rely on similar mechanisms, and it is not known whether dogs’ generalization biases rely on slow processes rooted in associations.

This study paves the way for more comparative investigations aimed at finding the potential influence of tool use in the tendency to attend to shape which is observed in humans. In addition, to shed more light on the potential relationship between vocabulary acquisition and shape bias, future studies could compare Gifted Word Learner dogs (i.e., dogs that rapidly acquire a large vocabulary of object names15) and typical dogs (dogs that lack this capacity) in generalization tasks.

Data availability

Data supporting these results is provided within this manuscript and Supplementary material.

References

Samuelson, L. K. & Bloom, P. The shape of controversy: What counts as an explanation of development? Introduction to the special section. Dev. Sci. 11, 183–184 (2008).

Landau, B., Smith, L. B. & Jones, S. S. The importance of shape in early lexical learning. Cogn. Dev. 3, 299–321 (1988).

Graham, S. A. & Poulin-Dubois, D. Infants’ reliance on shape to generalize novel labels to animate and inanimate objects. J. Child Lang. 26, 295–320 (1999).

Graham, S. A. & Diesendruck, G. Fifteen-month-old infants attend to shape over other perceptual properties in an induction task. Cogn. Dev. 25, 111–123 (2010).

Smith, L. B., Jones, S. S., Landau, B., Gershkoff-Stowe, L. & Samuelson, L. K. Object name learning provides on-the-job training for attention. Psychol. Sci. 13, 13–19 (2002).

Gershkoff-Stowe, L. & Smith, L. B. Shape and the first hundred nouns. Ch. Dev. 75, 1098–1114 (2004).

Jones, S. S. Late talkers show no shape bias in a novel name extension task. Dev. Sci. 6, 477–483 (2003).

Ayzenberg, V. & Lourenco, S. Perception of an object’s global shape is best described by a model of skeletal structure in human infants. eLife 11, e74943. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.74943 (2022).

Hupp, J. M. Demonstration of the shape bias without label extension. Infant Behav. Dev. 31(3), 511–517 (2008).

Santos, L. R., Miller, C. T. & Hauser, M. D. Representing tools: How two non-human primate species distinguish between the functionally relevant and irrelevant features of a tool. Anim. Cogn. 6, 269–281 (2003).

Hauser, M. D., Pearson, H. M. & Seelig, D. Ontogeny of tool-use in cotton-top tamarins (Sanguinus oedipus): Innate recognition of functionally relevant features. Anim. Behav. 64, 299–311 (2002).

Topal, J. et al. The dog as a model for understanding human social behavior. Adv. Study Behav. 39, 71–116 (2009).

Bunford, N., Andics, A., Kis, A., Miklósi, Á. & Gácsi, M. Canis familiaris as a model for non-invasive comparative neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 40, 438–452 (2017).

Dror, S., Sommese, A., Miklósi, Á., Temesi, A. & Fugazza, C. Multisensory mental representation of objects in typical and Gifted Word Learner dogs. Anim. Cogn. 25, 1557–1566 (2022).

Fugazza, C., Dror, S., Sommese, A., Temesi, A. & Miklósi, Á. Word learning dogs (Canis familiaris) provide an animal model for studying exceptional performance. Sci. Rep. 11, 14070 (2021).

Dror, S., Miklósi, Á., Sommese, A. & Fugazza, C. A citizen science model turns anecdotes into evidence by revealing similar characteristics among Gifted Word Learner dogs. Sci. Rep. 13, 21747 (2023).

Fugazza, C. & Miklósi, Á. Depths and limits of spontaneous categorization in a family dog. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

van der Zee, E., Zulch, H. & Mills, D. Word generalization by a dog (Canis familiaris): Is shape important?. PLoS ONE 7, e49382 (2012).

Biederman, I. Recognition by components: A theory of human image understanding. Psychol. Rev. 94, 115–147 (1987).

Polgár, Z., Miklósi, Á. & Gácsi, M. Strategies used by pet dogs for solving olfaction-based problems at various distances. PLoS ONE 10, e0131610 (2015).

Bräuer, J. & Belger, J. A ball is not a Kong: Odor representation and search behavior in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) of different education. J. Comp. Psychol. 132, 189–199 (2018).

Bremner, A. J. & Spence, C. The development of tactile perception. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 52, 227–268 (2017).

Xu, F., Dewar, K. & Perfors, A. Induction, overhypotheses, and the shape bias: Some arguments and evidence for rational constructivism. In The Origins of Object Knowledge (eds Hood, B. M. & Santos, L. R.) 263–284 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Pitteri, E., Mongillo, P., Carnier, P. & Marinelli, L. Hierarchical stimulus processing by dogs (Canis familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 17, 869–877 (2014).

Mongillo, P., Pitteri, E., Sambugaro, P., Carnier, P. & Marinelli, L. Global bias reliability in dogs (Canis familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 20, 257–265 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Brain Research Program NAP 3.0 of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (NAP2022-I-3/2022). Á.M. received funding from MTA-ELTE Comparative Ethology Research Group (MTA01 031). During the course of this study CF was also supported by the Hungarian Ethology Foundation (METAL). We are grateful to the owners who volunteered to participate with their dogs in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by C.F.; The experiments were run by U.K. (pilot version of the study), E.J., S.N. and A.S.; The statistical analysis was carried out by E.J.; The article was drafted by C.F., E.J. and A.M. and revised by all authors; All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Owners gave their informed consent for participating with their dogs in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fugazza, C., Jacques, E., Nostri, S. et al. Shape and texture biases in dogs’ generalization of trained objects. Sci Rep 14, 28077 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72244-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72244-y