Abstract

In India, the spatial coverage of air pollution data is not homogeneous due to the regionally restricted number of monitoring stations. In a such situation, utilising satellite data might greatly influence choices aimed at enhancing the environment. It is essential to estimate significant air contaminants, comprehend their health impacts, and anticipate air quality to safeguard public health from dangerous pollutants. The current study intends to investigate the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of important air pollutants, such as sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone, utilising Sentinel-5P TROPOMI satellite images. A comprehensive spatiotemporal analysis of air quality was conducted for the entire country with a special focus on five metro cities from 2019 to 2022, encompassing the pre-COVID-19, during-COVID-19, and current scenarios. Seasonal research revealed that air pollutant concentrations are highest in the winter, followed by the summer and monsoon, with the exception of ozone. Ozone had the greatest concentrations throughout the summer season. The analysis has revealed that NO2 hotspots are predominantly located in megacities, while SO2 hotspots are associated with industrial clusters. Delhi exhibits high levels of NO2 pollution, while Kolkata is highly affected by SO2 pollution compared to other major cities. Notably, there was an 11% increase in SO2 concentrations in Kolkata and a 20% increase in NO2 concentrations in Delhi from 2019 to 2022. The COVID-19 lockdown saw significant drops in NO2 concentrations in 2020; specifically, − 20% in Mumbai, − 18% in Delhi, − 14% in Kolkata, − 12% in Chennai, and − 15% in Hyderabad. This study provides valuable insights into the seasonal, monthly, and yearly behaviour of pollutants and offers a novel approach for hotspot analysis, aiding in the identification of major air pollution sources. The results offer valuable insights for developing effective strategies to tackle air pollution, safeguard public health, and improve the overall environmental quality in India. The study underscores the importance of satellite data analysis and presents a comprehensive assessment of the impact of the shutdown on air quality, laying the groundwork for evidence-based decision-making and long-term pollution mitigation efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution ranks second in terms of disease burden in India, following malnutrition, and is a significant contributor to respiratory ailments and associated infections1. Several cities throughout the country have been impacted by poor air quality2,3,4,5. Air pollution in the city is primarily caused by industrial activities, agricultural emissions (open burning), waste disposal, vehicle emissions, and construction activities surrounding the city2,3,4,5. Furthermore, air pollution is associated with ozone depletion, climatic change, and global warming, in addition to its detrimental effects on life on Earth6,7. Air pollution monitoring needs to be conducted promptly and with a very broad coverage in a nation such as India in order to detect and control future threats to human health, animal life, and plant life. The past few decades have encountered distinct challenges as a result of industrialization, unplanned urbanisation, and rapid population growth. Even though the intensity of emissions in India's main cities fluctuates considerably over time and space, their origins appear to be quite diverse. The increase in human activities, such as fuel combustion in vehicles, ships, and other transportation systems, as well as natural phenomena like volcanic eruptions and industrial activities like ore extraction, has collectively contributed to the elevated levels of air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and ozone (O3)4.

Investigating the potential of remote sensing data to enhance or replace information collected by ground-based air quality networks is highly intriguing. This is especially significant because satellite photos have the ability to offer a comprehensive view of the spread of pollution across a region over a period of time without being restricted to specific geographic locations8. Over half of the population is subjected to air pollution levels exceeding India's annual National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) of 40 µg/m39,10. State and central administrations in India have undertaken numerous initiatives to manage air quality in recent years. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has deployed Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations (CAAQMS) throughout India to monitor air quality. Notwithstanding the endeavours undertaken by CPCB, the spatial coverage of CAAQMS is not homogeneous due to the regionally restricted number of monitoring stations. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) manages and disseminates real-time air quality data from 438 continuous monitoring stations11. Notably, the majority of these monitoring stations are located in urban regions, specifically in megacities such as Delhi. There are only one to two continuous monitoring stations and a handful of manual air quality stations in smaller cities. In rural regions, ambient air quality monitoring stations are nearly non-existent. This paucity of data results in a limited understanding of spatial patterns of air pollutants at both the local and regional levels, making it difficult for planners and administrators to assess the impact of actions on air quality. Similarly, this has led to a limited number of health impact studies. An example is research carried out in Delhi, which demonstrated that with every 10–25 μg/m3 rise in PM2.5 concentrations elevates non-trauma all-cause mortality by 0.5–0.8%12. However, such studies are limited to large cities due to the unavailability of air quality data in other parts of the country. Hence, expanding the ambient air monitoring network is crucial for obtaining a thorough comprehension of a city's pollution levels and creating a precise framework to facilitate source apportionment investigations. In contrast to the sparse spatial distribution and temporal discontinuity of in-situ measurements, satellite observations offer daily coverage in its entirety.

The utilisation of satellite observations is increasingly recognised as a significant method for tracking the patterns of air pollutant concentrations, particularly in regions such as India where current emission data is scarce13,14. Satellite sensor that provides high-resolution measurements of atmospheric pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), and Aerosol optical depth (AOD)14. This sensor offers a unique opportunity to monitor air quality at a high spatial and temporal resolution, which is essential for analyzing air pollution in urban areas14. Satellite-mounted air quality monitoring technology, such as NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), can provide valuable information on air pollution trends and occurrences over large areas, such as an entire country. The TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), also utilised by NASA, is a different type of air quality monitoring device that is mounted on satellites. The novelty of this method is that measuring the intensity of sunlight reflected at different wavelengths and identifying the absorption traits of various atmospheric trace gases, they can examine multiple air pollutants like aerosols, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, ozone and formaldehyde14,15,16,17. This provides a holistic view of air quality. Also, multiple pollutant identification increases the feasibility of source identification especially for a country like India which faces vehicular pollution, industrial pollution, solid waste burning and stubble burning. The data from Sentinel-5P is accessible freely, thereby fostering study and advancement in the field of air quality monitoring and control. In many applications, data from satellite air quality monitoring and ground-based observations are merged to give a “larger picture” perspective of air quality15. The high spatial resolution of TROPOMI enables precise mapping of air pollutants at a fine level, facilitating the identification of hotspots and sources of pollution with exceptional accuracy.

Instruments such as TROPOMI, AIRS, GOME-2, and GEMS are used to monitor trace gases, atmospheric temperature, and aerosols from space. Geospatial approaches have several benefits compared to conventional ground-based sensors for monitoring air quality. These benefits enhance their utility in assessing pollution across vast regions with great precision14,15,16. However, satellite measurements are influenced by environmental factors that significantly impact the dynamics of air pollution8. The spatial resolution of Sentinel-5P TROPOMI data is 7 × 3.5 km, therefore, readings are averaged over a vast area17,18. Interpreting and using Sentinel-5P TROPOMI data for air quality monitoring and health effect evaluations should account for these limitations.

An analysis was conducted on the geographical and temporal features as well as the factors influencing the concentration of tropospheric NO2 in China during 2018. The study focused on the province and prefectural levels and utilised NO2 data from Sentinel-5P with TROPOMI19. Similarly, the TROPOMI satellite sensor was used to directly measure the intensity and spread of NO2 emissions from Paris20. Based on the analysis of NO2 pollution levels, it was observed that the highest emissions occurred during cold weekdays in February 2018. The findings of the study showed that the NOx emissions in 2018 were slightly lower, ranging from 5 to 15% below the estimated levels from 2011 to 2012.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) proclaimed coronavirus illness (COVID-19) to be a worldwide pandemic. The rapid spread and amplification of COVID-19 hampered life and activities. COVID-19 had a serious impact on India as well, and the Union Government imposed a multi-phase nationwide lockdown during the year 2020. Although COVID-19 had negative impact on the India's gross domestic product, poverty rate, health, and overall well-being, there have been temporary improvements in environmental aspects such as air quality, water quality, and GHG emissions21. The lockdown periods were effective in slowing the spread of active illnesses throughout the nation and were crucial in improving the air quality across the globe21,22,23,24. Limiting transportation, along with other human activities, reduced emissions and significantly decreased the concentration of air pollutants. A study reported a 20% reduction in NO2 concentrations in Delhi due to the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, based on TROPOMI and ground-based observation16. In a separate study, satellite datasets from TROPOMI and MODIS were used to analyse data from 41 cities in India during the COVID-19 lockdown. The analysis of satellite datasets indicated that there was a 13% decrease in NO2 levels observed during lockdown period in comparison to the period before the lockdown25. However, previous research using geospatial methods to study air pollution has been limited to specific regions, mostly important urban areas, lacking comprehensive hotspot analysis of the entire country. Also, these studies have mostly focused on limited number of air pollutants especially NOx concentrations in the study area.

The objective of this study is to use the advanced geospatial methodology of Sentinel 5P to identify and map the concentrations of gaseous air pollutants, including SO2, NO2, CO, and O3, and identify pollution hotspots in India. The study also aims to improve comprehension of the seasonal patterns of air pollution caused by gaseous pollutants as well as investigate the influence of reduced economic activities resulting from the COVID-19 lockdown on pollution concentrations in the country. Although there have been several studies on India that have shown a decrease in air pollution over megacities during lockdown, the novelty of this study is that it aims to comprehend the concentration map of the entire country for gaseous air pollutants and to identify pollution hotspots. This study will provide significant insights into the changing trends of air pollution in India, aiding policymakers and stakeholders in making well-informed decisions to improve air quality. This research aims to identify hotspot sites that expect instant attention and intervention to decrease pollution levels. In conclusion, our results can provide valued perceptions for developing targeted approaches to ease the effects of air pollution on both environment and public health.

Materials and methods

Study areas

India is located fully in the northern hemisphere, with its boundaries extending between latitudes 8° 4′ and 37° 6′ north of the Equator and longitudes 68° 7′ and 97° 25′ east of it. In this study, five major cities in India have been chosen, namely Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad, as our focus areas for investigating air pollution and its impact on human health (Fig. 1). These cities were selected based on several factors that make them suitable for studying air pollution in the Indian context. Firstly, the chosen cities were selected based on data availability, ensuring sufficient information for our study. Secondly, these cities were chosen due to their diverse geographical locations, representing different regions of India. This geographical diversity allows us to examine air pollution patterns across various climatic and geographical conditions. Mumbai is situated on the western coast, Delhi in the northern plains, Kolkata in the eastern coastal region, Chennai in the southern coastal area, and Hyderabad in the central-southern part of the country. Furthermore, the selected cities exhibit variations in meteorological parameters such as temperature ranges, wind patterns, and precipitation levels. These variations can influence the dispersion and concentration of air pollutants, emphasizing the importance of considering their impact on air quality. The high population density in Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad exacerbates air pollution caused by industrial activities, vehicle emissions, and energy consumption.

Delhi, the capital of India, ranks among the most polluted cities in the world. The city experiences air pollution due to vehicle emissions, industrial activities, building dust, and crop burning. Increased population density and urbanization contribute to elevated levels of air pollution. Despite having better air quality than Delhi, Mumbai, India's financial capital, nonetheless faces air pollution issues. The primary contributors to pollution in Mumbai are traffic, industrial activities, and coastal pollution. The city's close proximity to the Arabian Sea aids in the dispersion of pollution. Nevertheless, the ongoing process of urbanization and the expanding population pose a persistent danger to the quality of the air. Kolkata, a sprawling metropolis in eastern India, faces air pollution issues similar to those encountered in other urban areas. Kolkata is polluted by vehicle emissions, industrial operations, biomass burning, and coal-fired power stations. The climate and topography of Kolkata contribute to the escalation of air pollution. Chennai, a city in southeastern India, has better air quality compared to Delhi and Kolkata. The city continues to face air pollution problems as a result of automobile emissions, industrial activities, and dust. Chennai's close proximity to the Bay of Bengal allows pollution to disperse. Hyderabad, a city in southern India, has better air quality compared to Delhi and Kolkata. It is confronted with air pollution problems. Pollution in Hyderabad is mostly caused by car emissions, industrial activity, and dust particles.

It is important to note that although these cities have taken measures to address air pollution, continuous efforts are necessary to further improve air quality. The severity of air pollution can vary depending on weather patterns, geographical location, population density, and industrial activities. Monitoring and implementing effective measures to reduce pollution sources and promote sustainable practices remain crucial for these cities to ensure a healthier environment for their residents.

Data collection

Air pollutants were collected from Sentinel-5P data on the ESA website. The satellite data were collected for four years (2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022) over India for major pollutants because the Sentinel-5P mission introduced late 2018. These data were taken as the monthly, seasonal, and annual means for particular locations in column number density (CND) in mol/m2. Table 1 provides the data collected for various parameters.

To obtain air pollution data using Google Earth Engine, the datasets in the Google Earth Engine data catalog were explored, focusing on those providing measurements of pollutants like NO2, O3, CO, and SO2. These datasets were evaluated based on their coverage, resolution, and quality. The most suitable datasets were chosen, considering the area of interest, time frame, and compatibility with other data sources.

Methodology

The Sentinel-5 TROPOMI, operated by the European Space Agency (ESA), has garnered international acclaim for its comprehensive application in monitoring air quality parameters, including SO₂, NO₂, O₃, and CO26. Onboard the Sentinel 5 precursor (S5P), the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) offers high spatial resolution (3.5 × 7 km2 grid spacing for all mentioned gases) and temporal resolutions (24 h), providing open-source data at no cost27. Open-source data from the Sentinel-5P dataset was accessed using the Google Earth Engine interface. Utilizing Google Earth Engine's code editor with JavaScript, level 3 data is processed and exported into GeoTIFF format. Data for various pollutants, collected from January 2019 to December 2022, is then imported into ArcMap software and delineated according to a shapefile to generate maps. Subsequent geospatial analysis tools facilitate hotspot analysis, yielding initial results. The Zonal Statistics tool in ArcGIS, a geospatial analysis instrument, is employed to analyze and detect changes in pollutants, providing statistical insights within specified zonal boundaries.

To utilize the Zonal Statistics tool, two primary inputs are required: the pollutant raster layer and the zonal boundary layer. The pollutant raster layer provides data on the concentration or levels of a specific pollutant across a geographic area, formatted as a grid of cells, each representing a specific value or attribute related to the pollutant. The zonal boundary layer, which can be in either vector or raster format, defines the boundaries or regions of interest for which statistical values will be calculated. This layer can represent administrative boundaries, land use zones, or other predefined regions of interest.

Once the pollutant raster layer and zonal boundary layer are prepared, the Zonal Statistics tool in ArcGIS can be applied. This tool calculates various statistical values, such as average, sum, mean, maximum, and minimum, for each zone defined by the zonal boundary layer. By running the Zonal Statistics tool with the pollutant raster layer as the input and the zonal boundary layer as the zones, statistical information about pollutant concentrations within each zone can be obtained. This analysis aids in identifying hotspots or areas with high pollutant levels and understanding the spatial distribution and changes in pollutant concentrations across different regions. It is important to note that while the input value layer must be in raster format, the zonal boundary layer can be either vector or raster, providing flexibility in selecting the most suitable representation for analysis.

The Zonal Statistics tool in ArcGIS is extensively used in environmental and health research to quantify and compare pollutant levels, identify areas of concern, and develop targeted strategies for pollution control and mitigation.

The concentration of any pollutant from Sentinel-5P is expressed as Column Number Density (CND), which is the ratio of the slant column density to the total air mass factor, representing the tropospheric column average of air pollutants.

(Equation (1) Source: European space agency. https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/web/sentinel/technical-guides/sentinel-5p/level-2/doas-method).

Column number density (CND) map representation

Column number density maps serve as visual representations depicting the vertical concentration of specific gases in the atmosphere. These maps are widely employed to illustrate the spatial distribution and intensity of atmospheric pollutants such as NO2, SO2, CO, and O3 within a given region. The process involves dividing the atmosphere into discrete columns and measuring the concentration of each gas in these columns. The resulting data is represented using a colour gradient, where darker shades denote higher concentrations and lighter shades indicate lower concentrations. Leveraging satellite data, column number density maps provide a robust tool for visualizing the spatial patterns of air pollutants, facilitating the identification of pollution hotspots, monitoring temporal changes in pollutant levels, and supporting informed decision-making regarding environmental policies and regulations.

The analysis of air quality in India from 2019 to 2022 necessitates handling substantial datasets, with Sentinel datasets via Google Earth Engine proving instrumental for this purpose. This tool enables efficient data processing across extensive geographical areas. The methodology employed for analysing various air pollutants is outlined in Fig. 2, involving the collection of spatial and temporal data from Sentinel-5P TROPOMI through Google Earth Engine for monitoring air pollutant parameters.

This study conducts a comprehensive spatio-temporal analysis of air pollutants using Sentinel-5P datasets spanning from January 2019 to December 2022. ArcMap software, specifically utilizing its spatial analyst and hotspot analysis capabilities, was employed to analyse the data and visualize the results. Spatial analyst and hotspot analysis features within ArcMap facilitated the creation of graphical representations and hotspot analysis for pollutants like SO2, NO2, CO, and O3. Hotspot analysis identifies regions with significantly elevated or reduced pollutant concentrations, pinpointing areas of interest or potential pollution sources.

In this study, identified hotspot regions from the analysis were utilized as zonal boundary layers, with Sentinel-5P derived pollutant raster layers serving as input values for analysis. The application of the zonal statistics tool in ArcGIS generated statistical insights within these defined zones, including metrics such as average, total, mean, maximum, and minimum pollutant concentrations. This approach enabled a quantitative assessment of pollution severity in specific regions, offering critical insights into the spatial distribution and intensity of pollutants such as SO2, NO2, CO, and O3 within identified hotspot areas.

For pollutants like O3 and CO, which lack discrete hotspot regions, temporal change studies were conducted to assess variations in concentration over the four-year period. It is noted that hotspot analysis is not applicable to continuous layers like O3 and CO due to their absence of discrete hotspot regions. Nonetheless, temporal change studies provide insights into fluctuations in O3 and CO concentrations over time.

This study utilized Sentinel-5P datasets and ArcMap software to conduct a comprehensive spatio-temporal analysis of air pollutants in selected urban areas. Through hotspot analysis, zonal statistics, and change detection techniques, this research contributes valuable insights into the spatial distribution, concentration levels, and temporal dynamics of pollutants such as SO2, NO2, CO, and O3.

The Sentinel-5 TROPOMI excels in monitoring air quality parameters such as SO₂, NO₂, O₃, and CO. This study introduces an innovative methodology by integrating high-resolution, open-source satellite data from Sentinel-5P with Google Earth Engine (GEE) and ArcMap. This combination offers significant advancements in air quality monitoring by enabling the analysis of extensive datasets from January 2019 to December 2022, providing comprehensive spatio-temporal insights. Utilizing advanced geospatial techniques like hotspot analysis and zonal statistics, the methodology identifies pollution hotspots and analyzes spatial patterns. The flexible approach accommodates different pollutant types, employing discrete hotspot analysis for SO₂ and NO₂, and temporal change studies for O₃ and CO. This enhances its robustness and applicability across various environmental contexts. Visual tools such as column number density maps aid in identifying pollution hotspots and support informed decision-making for environmental policies. Overall, this methodology provides a comprehensive and flexible approach to air quality monitoring, yielding valuable insights into the spatial distribution and dynamics of pollutants in urban areas.

Results and discussion

Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of sulphur dioxide (SO2)

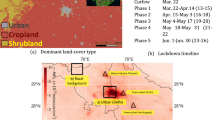

Figure 3 shows the seasonal variation of SO2 concentrations in India for the winter, summer, and monsoon seasons from 2019 to 2022. The map depicts different shades, ranging from dark brown, indicating high pollution levels, to dark blue, representing low pollution levels. The analysis shows that the SO2 content is at its minimum during the monsoon season and reaches its highest point in winter. The minimum concentration and lowering of the hotspot concentration during monsoons and the spreading of pollutants occurred in summer seasons is because of adverse environmental conditions like temperature, pressure, humidity, etc., which are responsible for stabilizing any gases.

Figure 3 shows that SO2 emissions are mostly concentrated in the Chota Nagpur Plateau, which is situated in the northeastern peninsular area and extends over the states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and West Bengal. SO2 hotspots are mostly located in high industrial clusters like Janjgir-Champa, Korba, Sambalpur, Sonbhadra, Jharsuguda, Solan, Panchkula, Angul, and Deogarh. The central region comprises states like Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. These states are home to a considerable number of coal-fired power plants, especially in cities such as Singrauli, Korba, and Raipur (Fig. 4)28. Our findings are in general agreement with the previous studies for 201929. The seasonal analysis of SO2 hotspots identified is presented in Table 2. Other industries like metallurgical industries, chemical fertiliser and cement manufacturing industries involves high-temperature combustion and the use of fossil fuels, which can release sulfur dioxide. Certain chemical production processes, such as the sulfuric acid manufacturing, can generate SO2 emissions. Chemical plants that use sulfur-containing compounds as feedstock or produce sulfur-containing products may also contribute to SO2 emissions. Hotspot locations vary with respect to various seasons. Power-plants and industries are responsible for 91% of SO2 emissions in India30. Power plants account for 46% of SO2 emissions in India, whereas emissions from various industries constitute the second largest source at 36%. The steel sector contributes nearly a quarter of these industrial emissions, followed by fertiliser facilities (14%), cement manufacturing (10%), and refineries (7%)30.

Distribution of power plants in India (Source:National Power Portal)28.

Metro Politian City analysis and inter comparison of SO2

Figure 5 presents the average yearly concentration of SO2 in different metro areas from 2019 to 2022, while Fig. 6 illustrates the monthly variation of SO2 pollution levels in metro cities over multiple years. The graph shows that COVID-19 reduced SO2 pollution in all cities in 2020 and 2021. There was a significant decline of 27.50% in SO2 concentrations in 2020 compared to 2019. Air quality improved temporarily under pandemic restrictions, causing this reduction. Similar temporary reductions in SO2 concentrations due to the COVID-19 lockdown have also been reported in other studies2,31. After the first drop, the graph shows pollution rising in stages. The return to pre-pandemic emission levels and economic activity may explain this increase. The graph shows the months with the lowest and highest SO2 concentrations from 2019 to 2022. The lowest pollution concentration over Hyderabad was 4.8 × 10–5 mol/m2 in September 2020. The highest concentration of 3.6 × 10–4 mol/m2 over Kolkata was in October 2022, signifying increased pollution. However, it is important to note that overall pollution levels have been increasing from 2019 to 2022. Nevertheless, following the initial decline, the graph shows a steady rise in pollution levels. This rise in emissions can be attributed to the resumption of economic activities and a return to pre-pandemic emission levels.

Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of nitrogen dioxide (NO2)

NO2 is mostly released into the atmosphere by the photochemical oxidation, combustion of fossil fuels that contain nitric oxide, soils, and plants7,32. Nitrogen dioxide is a highly reactive gas that reacts with various substances in the atmosphere to generate particulate matter (PM), ground-level ozone, and acid rain. Nitrogen dioxides have important consequences for both human health and climate32.

Figure 7 displays the spatio-temporal mapping of NO2 concentrations from 2019 to 2022. The data shows elevated NO2 levels in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, Central, Hilly, the Northeast, Northwest, and Peninsular regions of India. The places include Delhi, Janjgir, Jharsuguda, Delhi, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Dhanbad, Kolkata, and Sonbhadra. Clusters with high NO2 concentrations indicated that coal combustion and increased vehicle emissions would be the main sources of NO2. Road transport contributes to over 44% of the overall nitrogen oxide (NOX) emissions in India33. Various hotspots' NO2 concentrations are steadily declining in the pre-COVID-19 situation. The column density of NO2 for the whole of India was measured for yearly, seasonally, monthly, and intercomparison of metro cities. However, after the COVID-19 lockdown, NO2 values are gradually rising, and with that, new hotspots are emerging. Hotspots in India are mostly metropolitan cities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata because they have a higher vehicular population34.

Yearly variation and inter comparison of metro cities for NO2

Figure 8 presents the average yearly concentration of NO2 in different metro areas from 2019 to 2022. The highest average concentration recorded during this period was 0.00017 mol/m2 in 2021, while the lowest monthly average concentration was 0.00014 mol/m2 in 2020. Notably, there was a significant increase of 21% in the average concentration of NO2 from 2020 to 2021. This increase can be attributed to the rebound in pollution levels after the initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In comparison to other years, 2020 exhibited the lowest levels of NO2 pollution in all the cities. In 2019, Mumbai had a concentration of 0.0001 mol/m2, Delhi had 0.00015 mol/m2, Kolkata had 0.00008 mol/m2, Chennai had 0.00005 mol/m2, and Hyderabad had 0.000048 mol/m2. However, in 2020, the NO2 pollution concentrations decreased further, with Mumbai at 0.000099 mol/m2, Delhi at 0.00014 mol/m2, Kolkata at 0.00007 mol/m2, Chennai at 0.000042 mol/m2, and Hyderabad at 0.000041 mol/m2. By 2022, the NO2 pollution concentrations had increased, with Mumbai at 0.00017 mol/m2, Delhi at 0.00018 mol/m2, Kolkata at 0.00010 mol/m2, Chennai at 0.0000607 mol/m2, and Hyderabad at 0.000057 mol/m2. These comparisons highlight the variations in NO2 pollution levels across different years and cities, emphasizing the relatively lower levels observed in 2020.

In 2020, there was a decrease in NO2 pollution concentration compared to 2019 in the following cities: Mumbai (− 20%), Delhi (− 18%), Kolkata (− 14%), Chennai (− 12%), and Hyderabad (− 15%). However, by 2022, there was an increase in NO2 concentration compared to 2019 in these cities: Mumbai (13.33%), Delhi (20%), Kolkata (18.75%), Chennai (14%), and Hyderabad (8.7%). These percentage changes highlight the fluctuations in NO2 pollution levels over the years, with a decrease observed in 2020 followed by an increase in 2022 compared to the baseline year of 2019. COVID-19 impact depicts a period in 2020 from March to June, when the minimum concentration was 6 × 10–6 mol/m2 and the maximum was 0.00019 mol/m2 during the period of 2019 to 2022. From Fig. 9, Delhi has higher NO2 pollution after Mumbai and Kolkata for the period of four years, and its increasing trend from 2019 to 2022.

From Fig. 9, the NO2 concentration in Delhi and Kolkata has increased significantly compared to 2019, 2020, and 2021. Figure 9 shows a considerable amount of NO2 concentration changes throughout the seasons, decrease in concentration during April to October for the year of 2020 shows COVID- 19 impact. The monthly highest concentration of Delhi was 0.00019 mol/m2 in the May month of 2022. For Mumbai, it’s 0.00015 mol/m2 in August 2021. For Kolkata its 0.00014 mol/m2 in January 2022. For Hyderabad and Chennai its 6 × 10–5 mol/m2 in January 2022.

NO2 concentrations are also affected by seasonal changes; in winter, surrounding temperatures are lower than usual, so NO2 concentrations will stabilize in ambient air. As previously discussed, NO2 pollution is converted to nitric acid during precipitation, so the concentration of NO2 in the ambient air may be reduced16. Here, for hotspot consideration: Concentration > 9 × 10–5 mol/m2. According to Table 2, Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai are the same hotspots that appear in the winter, summer, and monsoon seasons; however, the concentration may increase or decrease depending on meteorological parameters. The major hotspots with the concentration of NO2: Janjgir in Chhattisgarh (0.000136 mol/m2), Delhi (0.000135 mol/m2) and Kolkata (0.000163 mol/m2). The hotspots for air pollution, specifically for the pollutants SO2 and NO2, have changed over time, particularly in the years before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Here is an explanation of the hotspot changes mentioned:

Hotspots before COVID-19: Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Korba: These cities were identified as hotspots for air pollution, specifically for SO2 and NO2, prior to the COVID-19 period. This means that these cities had higher concentrations of these pollutants compared to other regions during that time.

Hotspots in 2022: Newly developed hotspots: Dhanbad, Kolkata, and Sonbhadra: In 2022, these cities have emerged as new hotspots for air pollution (Table 3). It implies that these areas experienced a significant increase in the concentrations of SO2 and NO2 compared to previous years. The factors contributing to these new hotspots could include industrial activities, increased vehicular emissions, or other localized sources of pollution.

Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of carbon monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide is a colourless, odourless, tasteless, and toxic gas that is a significant air pollutant and contributes to the greenhouse effect, causing harm to humans and animals. The principal sources of CO include the combustion of biomass, fossil fuels, and the oxidation of hydrocarbons such as CH4 and Isoprene35. Fires, both natural and man-made, such as the burning of agricultural waste and crop leftovers, as well as forest and bushfires, are significant contributors of CO. Figure 10 provided the seasonal variation of CO pollution between 2019 and 2022. CO pollution levels in India’s northern region is raised by 20% in 2020–2021, while the eastern region, it is raised by 18%. Majorly polluted cities are all the metropolitan cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Chennai, etc. The increase in CO pollution in northern India is 4%, and it is around 5.5% in eastern India in 2021–2022. For the period of 2019 to 2022, the minimum concentration is 0.025 mol/m2 over Hyderabad, and the highest concentration is 0.055 mol/m2 over Delhi.

The concentration of carbon dioxide in a given region is determined by the region’s sources, sinks, and transport from other regions. A significant role is played by meteorology in the transport of CO. Seasonal patterns are also substantially impacted by the photochemical oxidation of CO precursors like CH4 and other hydrocarbons35. Concentrations of CO, which are predominantly generated by incomplete fuel combustion, are typically higher in areas where there is a high concentration of vehicles. Over the years, India has experienced a substantial growth in the number of motor vehicles, with the figures rising from 72.7 million in 2004 to approximately 295.8 million in 2020, and the trend continues to persist36. The emissions released by these vehicles, including pollutants like particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide, have a detrimental impact on the overall air quality, exacerbating pollution levels in cities37. It is imperative to acknowledge that areas with a substantial vehicular population may be significantly impacted by this pollutant. Various factors impact the emissions produced by vehicles, including but not limited to vehicle age, velocity, and emission rates. Motor vehicles emit considerable amount of hydrocarbons (HC), particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and carbon monoxide, alongside substantial quantities of photochemical oxides, into the atmosphere. The emissions in question negatively impact public health37.

Seasonally averaged CO concentrations in most part of the country is greatest in winter and lowest in monsoon, which is consistent with the seasonal cycle of CO observed in various regions of India35,38. The research area’s findings indicate that the colder months of the year saw the highest levels of air pollution (carbon monoxide), mostly because of the inversion phenomena or temperature inversion. When a layer of warm air sits on top of the cold air near the ground, it creates a temperature inversion. When these requirements are fulfilled, air stability is attained, and temperature rises to several hundred meters above the surface as height rises rather than falling. The same temperature inversion is crucial in air pollution because it helps to keep the atmosphere stable and, as a result, stops pollutants from moving vertically through the atmosphere35.

Yearly variation and inter comparison of metro cities for CO

In 2022 CO pollution concentration, the increase in concentration compared to 2019 is for Mumbai: 0.007 mol/m2, Delhi: 0.003 mol/m2, Kolkata: 0.004 mol/m2, Chennai: 0.003 mol/m2, Hyderabad: 0.004 mol/m2 (Fig. 11). In 2020 CO pollution concentration, the decrease in % compared to 2019 is for Mumbai: − 17.5%, Delhi: − 13.4%, Kolkata: − 12%, Chennai: − 10.5%, Hyderabad: − 12.2%. In 2022 CO pollution concentration, the increase in % of CO concentration compared to 2019 is for Mumbai: 18.9%, Delhi: 7%, Kolkata: 8%, Chennai: 8%, and Hyderabad: 10.81%.

Figure 12 shows, the decrease in CO concentration during the June to July sag for this particular year was primarily due to seasonal variation. COVID-19, result in a significant reduction in CO pollution in metro areas by May to Aug 2020. Delhi is also more polluted by CO compared to Mumbai, Chennai, and Hyderabad in the span of 4 years. In the period 2019 to 2022, the minimum CO concentration is 0.025 mol/m2 over Hyderabad and the maximum is 0.055 mol/m2 over Delhi. In Fig. 12, the monthly behaviour of CO pollution level shows a monthly sag.

Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of ozone (O3)

Ozone, a secondary pollutant in the troposphere, is a significant contributor to tropospheric chemistry due to its potent oxidising properties and generation of OH radicals, which in turn regulate the half-lives of various atmospheric components. The photochemistry of precursor gases such as CO and CH4 and the photochemistry of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) induced by lightning NOx and stratosphere troposphere exchange (STE) processes produce ozone in the troposphere39. Inhaling ground-level ozone can damage trees and agricultural commodities, in addition to causing adverse effects on respiratory health. Ozone, a secondary pollutant formed when O2 and O are exposed to slightly higher temperatures than usual, is a significant contributor to smog formation and must be accounted for when determining the seasonal behaviour of ozone for different cities39.

Figure 13 shows the spatio-temporal variation in ground level ozone concentrations over India during 2019 to 2022. Unlike other pollutants, ozone concentrations are more in summer followed by monsoon and least in winter. This may be due to high photochemical reactions involving primary pollutants leading to ozone formation in the atmosphere. Similarly, seasonal trend has been reported earlier38. Similarly, the average annual ozone concentration has increased from 2019 to 2022. In 2022 map shows highly brown colour over whole India it is showing increased in ozone pollution in 2022. Since it directly impacts agriculture, ozone pollution in India, particularly in the Indo-Gangetic plains, is a severe issue. Ozone (O3), the most prominent secondary air pollutant in the troposphere, is phytotoxic and drastically lowers agricultural yield40. In urban areas, O3 production is influenced by the oxidation of VOCs with shorter lifespans emitted from human-made and natural sources6. Tropospheric O3 generation relies on the amounts of VOC and nitrogen oxides (NOx)6. Ozone generation is encouraged at an ideal ratio of volatile organic compounds VOC to NOx of 5.5–141. In rural areas located downwind of urban areas, there is typically enough NOx to produce ozone (O3) from a contaminated air mass. Rural areas see elevated levels of O3 due to the influx of contaminated air from metropolitan areas. Polluted air masses transporting urban NOx remnants also include urban-derived VOCs. Although the highly reactive VOCs have been used up, less reactive VOCs remain to create O3. Air that has been moved can combine with NOx emissions in a downwind location to create O342. India’s economy is based on agriculture, and 58% of the population depends on it for a living. India's economy is demographically most diverse when it comes to agriculture, which ranks second globally in terms of farm productivity.

Yearly variation and inter comparison of metro cities for O3

Figure 14 shows the yearly comparison of O3 pollution of various metro cities. Mumbai’s long red candle shows major fluctuation throughout the years of 2019 to 2022. The mean concentration was consistently higher for Kolkata, followed by Delhi, Mumbai Chennai and Hyderabad. From Fig. 15, the concentration changes are highest in Delhi followed by Kolkata and Mumbai from 2019 to 2022. Figures 14 and 15 shows that in 2019 in Hyderabad it was higher fluctuation and average. The concentration is lower than Delhi but in 2022 it shows lower amount of concentration than Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai. It shows no significant variation in ozone concentration because the mean points in most cases are below the median line.

Figure 15 demonstrates the seasonal variation of ozone pollution levels. It indicates a noticeable decrease in O3 concentrations during June-July 2020, which corresponds to the period of COVID-19, when various restrictions and lockdown measures were implemented. This decline in O3 pollution can be attributed to reduced human activities, including decreased vehicular emissions and industrial operations33.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution in India

The findings of this study on spatiotemporal air quality analysis in India from 2019 to 2022 provide valuable insights into the changing pollution levels and hotspot patterns across the country. The study also highlighted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on air pollution levels. It was observed that concentrations of pollutants significantly decreased in 2020 and 2021 compared to other years. Notably, 2020 exhibited the lowest levels of NO2 pollution across all cities. While these reductions were temporary due to the pandemic-induced lockdowns, they underline the potential effectiveness of stringent measures in reducing air pollution.

The analysis of NO2 concentrations revealed both decreases and increases compared to the baseline year of 2019. In 2020, there were notable decreases in NO2 concentrations across all cities, with Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad experiencing reductions of − 20, − 18, − 14, − 12, and − 15%, respectively. However, in 2022, there were increases in NO2 concentrations compared to 2019, with Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad showing increases of 13.33, 20, 18.75, 14, and 8.7%, respectively. These findings emphasize the dynamic nature of pollutant concentrations and the need for continuous monitoring and mitigation efforts.

When comparing CO pollution levels among cities, Delhi consistently exhibits higher levels of CO pollution compared to Mumbai, Chennai, and Hyderabad over the span of four years. The maximum recorded concentration of CO during this period was 0.055 mol/m2 over Delhi, while the minimum concentration was 0.025 mol/m2 over Hyderabad. These findings emphasize the need for continuous monitoring and efforts to mitigate CO emissions, particularly in Delhi, to address the challenges associated with high CO pollution levels and improve air quality. The analysis highlights the variations in CO pollution levels over the years, with a significant decrease observed in 2020, likely due to the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on emissions, followed by an increase in 2022.

The analysis of ozone pollution concentrations in several cities across different years reveals interesting patterns. In 2019, Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad had O3 concentrations ranging from 0.114 to 0.119 mol/m2, indicating the level of ozone pollution present during that year. In 2020, all cities experienced a decrease in O3 pollution, with concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.116 mol/m2.

In the COVID-19 period, there has been a noticeable trend of increasing O3 pollution levels, suggesting a recovery in human activities and their impact on air pollution. It is important to consider factors such as weather patterns, emissions, and regional air quality conditions that can influence the increase in O3 concentration. The maximum concentration of ozone recorded in June 2022 was 0.13 mol/m2 over Delhi, indicating a relatively high level of pollution, while the minimum concentration of ozone during the COVID-19 period was 0.091 mol/m2 over Hyderabad, reflecting a comparatively lower level of pollution during that specific time frame. For ozone, 2020 had the lowest ozone pollution levels across all cities compared to other years. The concentrations varied between cities and showed a slight increase in 2022, but they remained lower than the levels observed in 2019. These variations in ozone pollution concentrations reflect the complex interplay of various factors, including emissions, atmospheric conditions, and meteorological influences, which can influence the formation and dispersion of ozone in different regions.

The study identified hotspots for both SO2 and NO2, with specific locations showing elevated concentrations of these pollutants. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Korba were identified as NO2 hotspots. However, in 2022, new hotspots emerged, including Dhanbad, Kolkata, and Sonbhadra. For SO2, hotspots were found to change seasonally, with a reduction in the number of hotspots during the monsoon season. Additionally, hotspots for NO2 were predominantly associated with megacities, while industrial clusters played a significant role in SO2 hotspots. Overall, this study contributes to understanding the behaviour of significant air pollutants in India. In addition to this analysis of air pollution in urban areas of the studied region during the lockdown, a parallel investigation of greenhouse gas emissions from the surrounding agricultural sectors and the same period is suggested since the hot weather can prompt an increase in these emissions, especially CO243.

Conclusions

The study used Sentinel-5P TROPOMI satellite images to conduct a comprehensive spatiotemporal analysis of air pollution in India during the period from 2019 to 2022. The results emphasize the need for efficient air pollution monitoring and control actions in India due to its rapid urbanization, large population, and alarming pollution levels. Conventional on-ground monitoring techniques for measuring pollution are inadequate in coverage and time-consuming, emphasizing the importance of leveraging remote sensing data for comprehensive assessments. The study observed that Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad underwent increase in their pollution levels during this period, ranging from 14 to 45%. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution was apparent, with significant declines observed in 2020 and 2021 compared to other years. Delhi and Kolkata were the most heavily polluted cities in terms of NO2 and SO2, respectively, compared to other metropolises. The study also showed that SO2 and NO2 hotspots decreased during the monsoon season. NO2 hotspots were mostly in megacities, while SO2 hotspots were in industrial clusters. Compared to other metropolises, Delhi and Kolkata have the highest NO2 and SO2 pollution. Delhi had 20% higher NO2 concentrations in 2022 than 2019, whereas Kolkata had 11% higher SO2 concentrations. The future scope of the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI programme has immense potential to expand its capabilities to monitor additional air pollutants and assess the health impacts of the measured air pollutants. Thus, the application of Sentinel-5P TROPOMI images proved to be an effective approach for urban air quality evaluation and hotspot analysis, with the potential to revolutionize air pollution monitoring in the country.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed duriing the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TROPOMI:

-

TROPOspheric monitoring instrument

- GHC:

-

Green house gases

- MODIS:

-

Moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer

- CPCB:

-

Central Pollution Control Board

- ESA:

-

European Space Agency

- SWIR:

-

Shortwave infrared

- PM:

-

Particulate matter

- CND:

-

Column number density

References

Abbafati, C. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249 (2020).

Praveen Kumar, R., Samuel, C., Raju, S. R. & Gautam, S. Air pollution in five Indian megacities during the Christmas and New Year celebration amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 36, 3653–3683 (2022).

Gokul, P. R., Mathew, A., Bhosale, A. & Nair, A. T. Spatio-temporal air quality analysis and PM2.5 prediction over Hyderabad City, India using artificial intelligence techniques. Ecol. Inform. 76, 102067 (2023).

Mallik, C. et al. Influence of regional emissions on SO2 concentrations over Bhubaneswar, a capital city in eastern India downwind of the Indian SO2 hotspots. Atmos. Environ. 209, 220–232 (2019).

Sharma, P., Chandra, A., Kaushik, S. C., Sharma, P. & Jain, S. Predicting violations of national ambient air quality standards using extreme value theory for Delhi city. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 3, 170–179 (2012).

Nair, A. T., Senthilnathan, J. & Nagendra, S. M. S. Emerging perspectives on VOC emissions from landfill sites: Impact on tropospheric chemistry and local air quality. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 121, 143–154 (2019).

Shikwambana, L., Mhangara, P. & Mbatha, N. Trend analysis and first time observations of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide in South Africa using TROPOMI/Sentinel-5 P data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 91, 102130 (2020).

Morillas, C., Alvarez, S., Pires, J. C. M., Garcia, A. J. & Martinez, S. Impact of the implementation of Madrid’s low emission zone on NO2 concentration using Sentinel-5P/TROPOMI data. Atmos. Environ. 320, 120326 (2024).

Ramachandran, A., Jain, N. K., Sharma, S. A. & Pallipad, J. Recent trends in tropospheric NO2 over India observed by SCIAMACHY: Identification of hot spots. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 4, 354–361 (2013).

Yarlagadda, B. et al. Climate and air pollution implications of potential energy infrastructure and policy measures in India. Energy Clim. Change 3, 100067 (2022).

Guttikunda, S., Ka, N., Ganguly, T. & Jawahar, P. Plugging the ambient air monitoring gaps in India’s national clean air programme (NCAP) airsheds. Atmos. Environ. 301, 119712 (2023).

Joshi, P. et al. Impact of acute exposure to ambient PM2.5 on non-trauma all-cause mortality in the megacity Delhi. Atmos. Environ. 259, 118548 (2021).

Ding, J. et al. NOx emissions in India derived from OMI satellite observations. Atmos. Environ. X 14, 100174 (2022).

Behera, M. D. et al. COVID-19 slowdown induced improvement in air quality in India: rapid assessment using Sentinel-5P TROPOMI data. Geocarto Int. 37, 8127–8147 (2022).

Ialongo, I., Virta, H., Eskes, H., Hovila, J. & Douros, J. Comparison of TROPOMI/Sentinel-5 Precursor NO2 observations with ground-based measurements in Helsinki. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 205–218 (2020).

Siddiqui, A., Chauhan, P., Halder, S., Devadas, V. & Kumar, P. Effect of COVID-19-induced lockdown on NO2 pollution using TROPOMI and ground-based CPCB observations in Delhi NCR, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 714 (2022).

Bodah, B. W. et al. Sentinel-5P TROPOMI satellite application for NO2 and CO studies aiming at environmental valuation. J. Clean. Prod. 357, 131960 (2022).

Fadhilah, N. A. Q., Ramadhania, N., Sanjaya, H., Sukojo, B. M. & Poespo, M. D. Spatio-temporal analysis of SO2 concentrations due to volcanic eruptions in indonesia using Sentinel-5P with earth engine platform. In 2022 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Geoscience, Electronics and Remote Sensing Technology (AGERS) 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1109/AGERS56232.2022.10093465 (2022).

Zheng, S., Wang, J., Sun, C., Zhang, X. & Kahn, M. E. Air pollution lowers Chinese urbanites’ expressed happiness on social media. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 237–243 (2019).

Lorente, A. et al. Quantification of nitrogen oxides emissions from build-up of pollution over Paris with TROPOMI. Sci. Rep. 9, 20033 (2019).

Bherwani, H., Gautam, S. & Gupta, A. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of impact of COVID-19 on sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Indian subcontinent with a focus on air quality. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 1019–1028 (2021).

Gautam, S. COVID-19: Air pollution remains low as people stay at home. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 13, 853–857 (2020).

Gupta, A. et al. Air pollution aggravating COVID-19 lethality? Exploration in Asian cities using statistical models. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 6408–6417 (2021).

Chelani, A. & Gautam, S. Lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study from Indian cities shows insignificant effects on persistent property of urban air quality. Geosci. Front. 13, 101284 (2022).

Vadrevu, K. P. et al. Spatial and temporal variations of air pollution over 41 cities of India during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–15 (2020).

Veefkind, J. P. et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 70–83 (2012).

Vellalassery, A. et al. Using TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) measurements and Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) CO modelling to understand the contribution of meteorology and emissions to an extreme air pollution event in India. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 5393–5414 (2021).

NPP. National Power Portal, Government of India. https://npp.gov.in/dashBoard/cp-map-dashboard (2020).

Tyagi, B., Choudhury, G., Vissa, N. K., Singh, J. & Tesche, M. Changing air pollution scenario during COVID-19: Redefining the hotspot regions over India. Environ. Pollut. 271, 116354 (2021).

Naja, M., Mallik, C., Sarangi, T., Sheel, V. & Lal, S. SO2 measurements at a high altitude site in the central Himalayas: Role of regional transport. Atmos. Environ. 99, 392–402 (2014).

Gautam, A. S. et al. Temporary reduction in air pollution due to anthropogenic activity switch-off during COVID-19 lockdown in northern parts of India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 8774–8797 (2021).

Virta, H., Ialongo, I., Szeląg, M. & Eskes, H. Estimating surface-level nitrogen dioxide concentrations from Sentinel-5P/TROPOMI observations in Finland. Atmos. Environ. 312, 119989 (2023).

Li, M. et al. MIX: a mosaic Asian anthropogenic emission inventory under the international collaboration framework of the MICS-Asia and HTAP. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 17(2), 935–963. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-935-2017 (2017).

Chinnasamy, P., Shah, Z. & Shahid, S. Impact of lockdown on air quality during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of India. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 51, 103–120 (2023).

Girach, I. A. & Nair, P. R. Carbon monoxide over Indian region as observed by MOPITT. Atmos. Environ. 99, 599–609 (2014).

RTYB. Road Transport Year Book (2019–20). Ministry of Road Transport and Highway Transport Research Wing, Government of India, (New Delhi, 2020).

Gajbhiye, M. D., Lakshmanan, S., Kumar, N., Bhattacharya, S. & Nishad, S. Effectiveness of India’s Bharat Stage mitigation measures in reducing vehicular emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 115, 103603 (2023).

Gaur, A., Tripathi, S. N., Kanawade, V. P., Tare, V. & Shukla, S. P. Four-year measurements of trace gases (SO2, NOx, CO, and O3) at an urban location, Kanpur, Northern India. J. Atmos. Chem. 71, 283–301 (2014).

Chandran, P. R. S. et al. Effect of meteorology on the variability of ozone in the troposphere and lower stratosphere over a tropical station Thumba (8.5°N, 76.9°E). J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 215, 105567 (2021).

Ojha, N. et al. Ozone and carbon monoxide over India during the summer monsoon: Regional emissions and transport. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 3013–3032 (2016).

Seinfeld, J. H. Atmospheric chemistry. In Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering (Elsevier, 2015).

Jain, C. D., Ratnam, M. V., Madhavan, B. L., Sindhu, S. & Kumar, A. H. Impact of regional transport on total OX (NO2 + O3) concentrations observed at a tropical rural location. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 13, 101408 (2022).

Mouhamad, R., Atiyah, A., Al-Azzawi, G., & Al-Bandawy, B. CO2 emissions in calcareous soil under various manure additions and water availability levels. DYSONA - Applied Science, 1(1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.30493/das.2020.220730 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Authors thankfully acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research for proving administrative and financial supports. Funding for this research was given under award numbers RGP2/411/44 by the Deanship of Scientific Research; King Khalid University, Ministry of Education, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. P.R.S. A.T.N and C.R. Conceptualization; A.M. P.R.S. A.T.N and C.R. methodology; A.M. P.R.S. J.M. and C.R. writing—original draft preparation; A.M. P.R.S. A.T.N. A.A.B. C.R. M.M.A. and H.G.A. writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research is carried out in compliance with transparency, moral values, honesty, and hard work. No humans nor animals are involved in the work. This work is neither a repetition of any work nor a copied key data from others’ work. As per our knowledge and belief, the methodology, findings, and conclusions made here belong to the original research work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathew, A., Shekar, P.R., Nair, A.T. et al. Unveiling urban air quality dynamics during COVID-19: a Sentinel-5P TROPOMI hotspot analysis. Sci Rep 14, 21624 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72276-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72276-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Monitoring urban air quality in lahore: a combined approach using ground measurements and sentinel 5P data

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2026)

-

Comparison of air pollution before and during COVID-19 pandemic in 30 metropolitan cities and Zonguldak Province in Türkiye

Sādhanā (2025)

-

Urban air quality modeling and health impact analysis using geospatial methods and machine learning algorithms

Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science (2025)