Abstract

Accurate reservoir characterization is necessary to effectively monitor, manage, and increase production. A seismic inversion methodology using a genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) technique is proposed in this study to characterize the reservoir both qualitatively and quantitatively. It is usually difficult and expensive to map deeper reservoirs in exploratory operations when using conventional approaches for reservoir characterization hence inversion based on advanced technique (GA and PSO) is proposed in this study. The main goal is to use GA and PSO to significantly lower the fitness (error) function between real seismic data and modeled synthetic data, which will allow us to estimate subsurface properties and accurately characterize the reservoir. Both techniques estimate subsurface properties in a comparable manner. Consequently, a qualitative and quantitative comparison is conducted between these two algorithms. Using two synthetic data and one real data from the Blackfoot field in Canada, the study examined subsurface acoustic impedance and porosity in the inter-well zone. Porosity and acoustic impedance are layer features, but seismic data is an interface property, hence these characteristics provide more useful and applicable reservoir information. The inverted results aid in the understanding of seismic data by providing incredibly high-resolution images of the subsurface. Both the GA and the PSO algorithms deliver outstanding results for both simulated and real data. The inverted section accurately delineated a high porosity zone (\(>20\%\)) that supported the high seismic amplitude anomaly by having a low acoustic impedance (6000–8500 m/s\(*\) g/cc). This unusual zone is categorized as a reservoir (sand channel) and is located in the 1040–1065 ms time range. In this inversion process, after 400 iterations, the fitness error falls from 1 to 0.88 using GA optimization, compared to 1 to 0.25 using PSO. The convergence time for GA is 670,680 s, but the convergence time for PSO optimization is 356,400 s, showing that the former requires \(88\%\) more time than the latter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In combined exploration and reservoir investigations, reservoir characterization from seismic data is essential because it provides very detailed geological information and characteristics of the reservoir. According to Li and Zhang1, the oil and gas industries now extensively rely on the estimation of reservoir features using geophysical techniques for prospect appraisal, reservoir characterization, and geological modeling. When employing conventional methodologies for reservoir characterization, the problem of revealing deeper reservoirs in exploratory operations has always been challenging and expensive. A remedy for this problem has been found in coupled seismic inversion and reservoir characterization since it provides essential information about exploration and production operations. As a result, combined seismic inversion and reservoir characterization are used by the oil industry as a tool for exploration and production processes all over the world2,3,4. From seismic and well-log data, petrophysical models are extracted via seismic inversion. The subsurface models can also be established using the inversion of seismic data alone in the absence of well-log data5. The oil and gas business commonly uses seismic inversion techniques to identify subterranean reservoirs. The elastic parameters like impedance (Z), P-wave velocity (\(V_s\)), S-wave velocity (\(V_s\)), and density (\(\rho\)) can all be calculated using seismic inversion6. The lame parameters, which are affected by fluid saturation in rocks, can also be found using inverted impedance models. The fundamental challenge with seismic inversions is that there could be multiple solutions for a given situation. By incorporating additional information, which is frequently derived from the well-log data, the uncertainty of non-uniqueness can be reduced. Seismic inversion can be made more efficient by using both local and global optimization techniques, such as simulated annealing, branch and bound, Bayesian search (partition), genetic algorithms (GAs), and others. Local optimization techniques include least-squares optimization, Pattern Search, conjugate gradient, steepest descent, quasi-Newton, and Newton7. A wide range of optimization techniques, such as model-based inversion, colored inversion, sparse spike inversion (SSI), band-limited inversion (BLI), etc., are used in numerous examples of reservoir characterization on post-stack seismic data and local well-log data1,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Post-stack seismic data was employed in this study to characterize the Blackfoot reservoir, using seismic inversion based on particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithm.

The main goals of this study are to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of seismic inversion based on global optimization of particle swarm optimization (PSO) & genetic algorithm (GA) and to identify potentially productive zones using impedance and porosity in the Blackfoot field, Alberta, Canada. One of the bio-inspired algorithms is particle swarm optimization (PSO), which searches for the best solution in the problem space. It doesn’t depend on the gradient or any other differential form of the objective, in contrast to other optimization techniques, and only needs the objective function. Initially, PSO forms a starting swarm by randomly placing a collection of particles within a feasible solution space, with each particle assessed by the objective function13. Subsequently, each particle moves at a specific velocity within the search space, its velocity dynamically adjusted based on its movement and that of other particles. Typically, particles tend to gravitate towards the path of the optimal particle, converging towards the best solution over successive iterations14. During each iteration, every particle tracks two key extremes, its personal best, representing the optimal position it has achieved thus far, and the global best, indicating the best position across all particles in the swarm15. By adhering to these principles, each particle progressively converges to the same position over iterations, representing the optimal solution to the optimization problem13,14. With less parameters to change, particle swarm optimization (PSO) is a novel approach with an easy-to-implement principle. Since J. Kennedy and R. C. Eberhart first proposed the algorithm in 1995, the approach has drawn the attention of numerous academics. Its application in seismic inversion is still in the research stage, despite its widespread use. PSO seismic inversion is not now directly applied in the majority of commercial applications. Scholars have made significant strides from the early numerical modeling of PSO impedance inversion to the current implementation of PSO and its improved algorithm for real seismic data. Previous authors16 have used PSO for the noise-corrupted synthetic sounding data sets over a multilayered 1D earth model by using DC, induced polarization (IP), and magnetotelluric (MT) methods. Authors17have used Inversion of seismic refraction data using particle swarm optimization where they have confirmed the ability and reliability of PSO in inverting seismic refraction data to model 1D P-wave velocity structures with acceptable misfit and convergence speed.

On the other hand, the genetic algorithm (GA), which is a subset of the larger class of evolutionary algorithms (EA), is a metaheuristic technique used in computer science and operations research that draws inspiration from the process of natural selection18. When solving optimization and search issues, genetic algorithms commonly use biologically inspired operators like mutation, crossover, and selection. This is accomplished by determining the model’s (objective function’s) least feasible mismatch with the seismic data. Because the observed seismic data may be thought of as a forward model in which the seismic wavelet is convolved with the earth’s reflectivity series, the inversion process is model-driven19. This process can be described by stochastic or deterministic methods. With no information loss, these techniques can generate quantifiable genuine model parameters of subsurface rock attributes (earth models), such as impedance, porosity, compressional velocity (\(V_P\)), and reflectivity, resulting in a practical global optimum solution. These methods help to improve thin-bed stratigraphy recovery, volumetric estimation, wavelet effects removal, sand body quantitative characterization, tuning problems, and seismic data de-noising, in general20. The results of global inversion procedures can lead to greater resolvability and a more favorable correlation between seismic data and lithology. Specifically, Markov chain analysis is used21 to demonstrate that both the GA and the simulated annealing (SA) approach are capable of finding an optimal solution. The GA is one of the most significant algorithms among the stochastic methods discussed above and it has been used to solve inversion problems in a variety of scientific fields, including geophysics. The GA is applied to invert for many sets of synthetic seismic refraction data22 and also applied to amplitude variation with offset inversion and prestack full-waveform inversion23,24,25. Further, the GA is used26,27 to invert for reservoir properties. Nevertheless, the poor performance of stochastic algorithms, such as the GA, in local searches restricts the pace of the search. Several stochastic algorithms can find an optimal solution, as demonstrated in21,28.

Another important factor in inverse problems is the selection of the inversion algorithm. Simple inversion issues can be solved with local search techniques29. However, these techniques are insufficient to achieve the global optimum in complex circumstances, such as the inversion of reservoir characteristics. However, global geometry optimization problems can be solved by stochastic algorithms30,31, but it takes a long time for these algorithms to leave the local optimum and arrive at the global optimum. This places additional restrictions on how quickly stochastic algorithms can search. By analyzing previous comparative studies by authors such as32 which have explored the advantages and disadvantages of swarm intelligence algorithms over GA, by conducting experiments on synthetic data only. Also, the authors33 applied PSO and GA for the inversion of Rayleigh wave dispersion curves. However, our study not only shows the PSO’s superior performance in achieving global minima but also provides a detailed comparative analysis of GA and PSO, highlighting their performance differences in terms of iteration efficiency and resolution accuracy. For reservoir characterization, a thorough numerical simulation of PSO and GA wave impedance inversion is therefore performed in this work, along with a qualitative and quantitative comparison of the two approaches. In the discipline of geophysics, GA is a well-established method, whereas PSO is still in its infancy. As such, comparing the two becomes crucial to determining which is the best in the competition for convergence time using post-stack seismic data from Blackfoot, Canada.

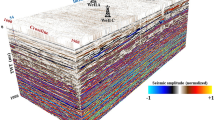

The post-stack seismic data from the Blackfoot field in Alberta, Canada, coupled with well log data, are utilized to show how GA and PSO can be used to invert seismic data. In the Canadian province of Alberta, Blackfoot Field is situated southeast of Strathmore City34. To better understand the clastic Beaver Hill Lake carbonates and the reef-prone Glauconitic channel, the data was gathered in two overlapping patches35. 708 shots (seismic source), distributed across 690 fixed recording channels, make up the collection36. The data has a vertical bandwidth of 5–90 Hz and a horizontal bandwidth of 5–50 Hz. Data from the first patch i.e. reef-prone Glauconitic channel is used in this study. Simin37 provides a detailed description of the processing techniques applied to the vertical and horizontal component data.

Methodology

Genetic algorithm

Holland (1975) developed genetic algorithms (GAs), which were the first global optimization techniques used in this investigation. The more prevalent category of evolutionary algorithms includes genetic algorithms (GAs), which are adaptive heuristic search engines. On the concepts of natural selection and genetics, genetic algorithms are built. Natural selection, the mechanism that propels biological evolution, is the foundation of the genetic algorithm, which resolves both constrained and unconstrained optimization issues. GA works by repeatedly changing each unique solution in a population. The genetic algorithm chooses at random each unique solution, known as a parent, and utilizes it to create a new solution, known as children. After a significant number of generations, the problem’s solution approaches the optimum38. The evolutionary algorithm is used in many study domains to optimize discontinuous, non-differentiable, stochastic, or highly nonlinear conditions by decreasing errors between observed and modeled data. In this study, a genetic algorithm is employed to determine the subsurface acoustic impedance and porosity by minimizing the discrepancy between the observed and modeled seismic traces. To build a new population from the present population, the genetic algorithm performs three main processes, selection, crossover, and mutation22.

Using a selection technique based on fitness scores, individual models are coupled. Whether or not they are selected depends on the model’s fitness value. The likelihood of selecting a model with very high fitness values is much higher than selecting a model with low fitness values. This is because more often the models that suit the data will be chosen for replication. The model’s fitness value determines the selection probability39. The crossover genetic operator is applied after the models have been chosen and coupled. Transferring genetic data between paired models is the basic tenet of a crossover. The crossover could also be seen as a means of information sharing between paired models, leading to the creation of new models40. Geophysical difficulties might involve either single-point crossover or multipoint crossover. In the context of GA being applied to geophysical problems, the choice between single-point crossover and multipoint crossover depends on several factors related to the specific characteristics of the problem being solved and the goals of the optimization process. If the problem involves a relatively simple or smooth search space, a single-point crossover may be sufficient to navigate the space effectively. Since, our goal is to explore a diverse set of solutions and avoid premature convergence to local optima, So, multipoint crossover is more suitable here. The fundamental idea behind the single-point crossover is the use of a uniform probability distribution to choose the model’s one-bit location at random. The right side of the selected bit is then exchanged between two models, resulting in the creation of a new model. On the other hand, the multipoint crossover method randomly chooses a bit location and then shifts all bits up to this bit throughout the matched models. A further bit location is chosen at random from the second model parameter, and any bits that immediately follow this bit are again exchanged. Every model parameter goes through this process41.

The mutation, which adds randomization to the crossover, is adopted in the final stage. The mutation process often happens during the crossover phase. The number of walks in the model space is controlled by the mutation rate, which is established by a uniform probability distribution. Because there won’t be many walks in the model space due to the low mutation frequency, the problem will be transformed shortly. On the other hand, the high mutation probability will result in a lot of space-based random walks, but this can delay the algorithm’s convergence42. In the process of mutation, one new solution (children) from the crossing is chosen and employed as a parent. In order to produce unpredictability in the result, two mutation sites are selected and switched between one another. The following is how to apply the genetic algorithm.

Step 1: Generate the initial Populations

Step 2: Define search space by deciding lower and upper limit.

Step 3: Calculates the reflection coefficients.

whereas \(R_i\) is reflectivity at \(i^{th}\) interface, \(Z_{i+1}\) is impedance at \((i+1)^{th}\) layer, \(Z_i\) is impedance at \(i^{th}\) layer. Step 4: Creates traces synthetic using following formula.

Where \(S_{mod}\) is synthetic trace, R is reflectivity series, W is wavelet and \(*\) is convolution operator.

Step 5: Evaluates the merit function

Where e is the difference between model and observation, \(S_{mod\,i}\) is modeled data at the ith sample, \(S_{obj\,i}\) is observed data at the ith sample, and \(Z_{mod\,i}\) is the modeled impedance at ith time sample n is the total number of sample points in the data and \(Z_{obj\,i}\) is the observed impedance at ith sample. \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) are weights applied to the two terms, respectively. In most of the cases, these weights are chosen as unity i.e. \(W_1= W_2= 1\). In the context of single data inversion, such as seismic data, these parameters are typically assigned a value of 1. However, when dealing with the inversion of multiple geophysical datasets, these parameters may vary depending on the data type and associated parameters. For instance, in joint inversion, which aims to integrate various geophysical data types like gravity, magnetotelluric, and seismic data, these parameters cannot be uniformly set to one. Instead, their values depend on the relative importance or weight assigned to each type of data.

Step 6: Selects the individuals to be combined based on their merit score

Step 7: Combines the selected individuals using the crossing point c

and

Step 8: Introduces a mutation be means of the operator M

Step 9: Selects the individuals that will follow to the next generation by means of the operator S

Step 10: Creates the next generation

Step 11: Final Result (\(Z_p\))

Particle swarm optimization

The foraging and social activities of the swarm serve as the inspiration for particle swarm optimization (PSO). PSO imitate the action or the phenomenon, such as a bird flock or a school of fish. The algorithm of PSO was developed by Eberhart and Kennely43. The PSO is used to optimize continuous non-linear function by direct search approach and does not need any gradient information like other optimization needed. The benefit of not using gradient information is that, it can be used for discontinuous function. PSO begins with a randomly initialised population, much like a genetic algorithm (GA). Solutions, unlike GA operators, are given randomised velocities to explore the search space. In PSO, a particle is a solution of any kind. Three distinct features of PSO are given below.

-

1.

\(p_{best\,i}\) : the best outcome (fitness) that particle i has so far attained

-

2.

\(g_{best}\): the most effective outcome (fitness) that any swarm particle has yet attained.

-

3.

For exploring and utilising the search space to find the best answer, use velocity and position updates.

Now we will start with the position update first because it will behave like a variation operator that will help to change the current position of a particle to its position.

The following updates to particle (i) velocity are made.

Where w is an inertial weighting factor that linearly decreases with the number of iterations to give the algorithm strong global search performance at the beginning and strong local search performance at the end. The numbers \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), also known as learning factors or acceleration factors, are positive constants. The particle’s step length to reach its current best position is controlled by \(c_1\), while the particle’s step length to reach the world’s best position is controlled by \(c_2\). Kennedy13 conducted a number of parameter experiments and found that when the algorithm behaves better, the sum of \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) should be around 4.0. The random values \(r_1\) and \(_2\) fall between [0, 1], while t is the iteration number. In order to prevent particle velocities that are insufficient for a particle to fly over the ideal position, the maximum speed of particles must be limited. We refer to each particle’s top speed as having a maximum of \(V_{max}\), and if \(V_{max} < v_{id}\) , we set \(V_{max}=v_{id}\); if \(V_{max}>v_{id}\), we set \(-V_{max}=v_{id}\)44. The particle’s initial positions and speeds are produced at random, and the above two equations are iterated until a workable solution is obtained. Equation 12 involves three components,

-

1.

Momentum part (\(wv_{id}(t)\)) : the first component is the particle’s earlier velocity, which guarantees the particle’s flight.

-

2.

Congnitive part \(c_1 r_1 (p_{id} (t)-x_{id} (t))\) the second component is a vector that points from the particle’s present position to its own best position.

-

3.

Social part \(c_2 r_2 (g_{id} (t)-x_{id} (t))\) : final component is a vector from its current location to the swarm’s best position45.

Each particle adjusted its speed in accordance with Eq.(11) throughout each iteration. Fly to the new position in accordance to Eq.(12)17.

Algorithm test

1D synthetic model

The GA and PSO approach is used to estimate acoustic impedance first using synthetic data followed by real data application. For this, an acoustic impedance-based seventeen-layer Earth model is used with a range of AI is \(7040m/s*g/cc\), \(9065m/s*g/cc\), \(5740m/s*g/cc\), \(7425m/s*g/cc\), \(10040m/s*g/cc\), \(8225m/s*g/cc\), \(9500m/s*g/cc\), \(11700m/s*g/cc\), \(6300m/s*g/cc\),\(10455m/s*g/cc\), \(7425m/s*g/cc\), \(13500m/s*g/cc\), \(11700m/s*g/cc\), \(10000m/s*g/cc\), \(14144m/s*g/cc\), \(15568m/s*g/cc\), \(12720m/s*g/cc\). We employed genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization approaches to minimize the error between observed and simulated data after creating synthetic data sets.

The resulting 1-D post-stack seismic data were inverted to get the impedance values for each layer. This study uses a forward model for a 17-layered scenario. Each layer was thought to be homogeneous, with uniform velocity and density throughout. Each layer’s depth, velocity, and density were all model parameters. After that, the same model was inverted using GA and PSO, and model parameters were computed. The related results are presented in Fig. 1. Tracks 1 and 2 of Fig. 1 illustrate the velocity and density of the subsurface geology model. In contrast, tracks 3 show the comparison of original impedance (black) and predicted impedances from the genetic method (green) and particle swarm optimization(red), respectively. By minimizing the error from eq. (4), the best outcomes are estimated. The calculated P-impedances agree well with their real models, and the correlation coefficients for GA and PSO are estimated to be 0.99 and 0.99, respectively. Also in Fig. 1, tracks 4 and 5 compare synthetic traces from modeled impedance (black) and reproduced synthetic traces from inverted impedance estimated from GA (green) and PSO (red) show a very close match with each other with 0.99 and 0.98 correlation respectively.

As a quality check of inverted data, a cross plot between inverted and original impedance is constructed and exhibited in Fig. 2. The image of track one depicts the best-fit line as a solid blue line, and the red and blue circles show inverted impedance which is the outcome of applying GA and PSO algorithms. From this figure, we see that the circles are too close to the best-fitting line. The proximity of the scatter points to the best-fit line indicates that the inverted results are extremely near to the true value, confirming the algorithm’s effectiveness. Table 1 compares observed and modeled impedance for each layer estimated by genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization. Figure 2b depicts error analysis for the genetic method (top) and particle swarm optimization (bottom). In the entire process of inversion, PSO takes 34 sec and GA takes 54 sec to archive the optimal solution. According to the observations and numerical analysis, the PSO produces better outcomes than the GA approaches.

Synthetic wedge model

The wedge model is a key component of the interpreter’s toolkit for coal seams. It is widely used to comprehend the geologic significance of seismic amplitudes below a reservoir’s tuning thickness. Tuning describes the modification of seismic amplitudes brought on by beneficial and harmful interference from overlapping seismic reflections. When numerous closely spaced contacts reflect a downward wave, this occurs. If the resulting upgoing reflections coincide, the reflected seismic energy will interact with and change the amplitude response of the true geology.

Further, we examine this using a constructed zero-offset synthetic wedge model (Fig. 3). Linearly, the seam thickness rises from 70 to 90 m. We can observe that the wedge’s amplitude response is constant. This shows that the top and bottom of the wedge have distinct reflections with no interference. Figure 3a, b depict a theoretical wedge model of a pinch-out coal seam and a forward seismic profile based on the convolution model. Figure 3c, d show the impedance section estimated using a genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization method respectively recognizing two distinct events that are thinner than the tuning thickness. The analysis demonstrates that the PSO estimates superior resolution than the genetic algorithms.

Blackfoot data application

To predict the acoustic impedance and porosity in the inter-well zone, seismic data from the Blackfoot field in Canada is subjected to particle swarm optimization and the Genetic Algorithm. Although the entire volume of seismic data is accessible, only a cross-section at inline 1 and crosslines 1 to 50 are utilized to invert them by taking into account the long duration of convergence. Before performing inversion, first need to calculate the relationship between porosity reflectivity (\(R_{\phi }\)) and impedance reflectivity (\(R_Z\)), and the following formula is used46.

Where \(z_{i+1}\) and \(\phi _{i+1}\) is (i+1)th layer impedance and porosity whereas, \(z_i\) and \(\phi _i\) is the ith layer impedance and porosity respectively47. These equations (4 and 5) are used to estimate the correlation factor (g) which is nothing but the slope of the fitted line. Figure 4a shows the cross plot of porosity reflectivity and acoustic reflectivity and the best-fit line gives a slope of −0.14. This correlation factor is used to generate a porosity wavelet by multiplying the g factor with the impedance wavelet which is extracted directly from the seismic data. Figure 4b compares the porosity wavelet and the impedance wavelet and one can see that both are in reverse polarity and that porosity and impedance are inversely proportional to one another.

a Crossplot between acoustic reflectivity and porosity reflectivity for well \(01-08\_logs\) is marked by a best linear trend which gives the correlation factor (\(g = -0.14\)), and b compares statistical wavelet (black) and porosity wavelet (red) generated by multiplication of correlation factor to the statistical wavelet.

The application to real data is performed in two steps, first, a composite trace close to the well locations is derived from the seismic section, and both algorithms (GA and PSO) are applied to it. According to the theory, the composite trace is quite close to the well, and the same stratigraphy may be expected in the well as well as the composite trace. Both techniques explored begin with low-frequency acoustic impedance and porosity from the well-log and utilize it as a model to address constraints. The main advantage of beginning with a model based on well-log data is that it shortens the lengthy convergence process to these global optimization methods. In addition, a lower bound and an upper bound are used to further limit the search space inside the desired range. However, in this study, we used upper and lower bounds based on the original model built using well-log data. The process is as follows. The phenotype comprises one binary strings. Every individual is depicted by an Nx101 matrix, where N signifies the number of layers, 101 bytes indicates the chain’s length, and the parameter Zp and porosity is represented. For generating the initial population, uniform probability functions were linked to the ranges of the initial models, including impedance within ± 1000m/s*g/cc and porosity within (\(\pm 10\%\)) . Figure 5 depicts the inversion analysis result for the composite trace near wells 01-08, as calculated using the genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization, respectively. Figure 5 depicts the original model (blue solid lines) as well as the lower and upper bounds (dotted blue lines). The first and second panels of Fig. 5 show a comparison of the original (black solid line) and inverted acoustic impedance (red solid line) whereas panels 3 and 4 compare the original (black solid line) and inverted porosity trace (red solid line). The AI and porosity created from well-defined data and inverted data have a good agreement with each other. The peak-to-peak of acoustic impedances and porosity do not match since well log data has a frequency range of 20 to 40 kHz, whereas seismic frequency typically ranges from 10 to 80 Hz. The correlation between well-log impedance and inverted impedance illustrated by GA and PSO is 0.71 and 0.66 and well-log porosity and inverted porosity are 0.63 and 0.63 respectively. Table 2 contains the other statistical comparisons between well data and inverted data. According to the analysis, the inverted outcomes of PSO and GA are extremely near to the original, so the method performance is good. From the Fig. 5 we highlighted the target zone is between 1040 and 1065 ms which shows low impedance and high porosity values from original as well as inverted data.

After that, the global optimization techniques (GA and PSO) are applied trace by trace to the CDP stack section to determine the impedance and porosity volume. Figure 6a displays a cross-section at inline 1 and crosslines 1 to 50 with a two-way travel time of \(900-1100ms\) of Blackfoot seismic data. Inversion is done trace by trace, and once all seismic traces have been inverted using GA and PSO, the results are plotted against two-way travel time and shown in Fig. 6b, c, respectively. Figure 6b, c clearly show that the 01–08 log impedance and inverted impedance have a good match and the low impedance zone is between 1040 and 1065 ms. The boundary at 1040 ms is designated as a high reflecting layer because the high impedance layer (\(>11{,}000 m/s*g/cc\)) surrounds the low impedance zone (6500–8500 m/s*g/cc). The visual analysis depicts that the impedance estimated by the PSO methods has a higher resolution as compared with GA. The layers are more clearly visible in PSO-derived impedance as compared with GA.

Following that, Fig. 7 shows the porosity volume that was created by projecting porosity throughout the whole seismic section. Figure 7a depicts post-stack seismic data, Fig. 7b, c show the variation of the porosity section at inline 1 with a two-way travel time of 900–1100 milliseconds derived using GA and PSO techniques respectively. The inverted results show a very high resolution of the subsurface with layer information whereas input seismic data only provides interface information. It is noted that the porosity varies from 1 to 30 percent in the study region and the high porosity zone (\(>20\%\)) is between 1040 and 1065ms two-way travel time. The well-log porosity also shows a very good agreement with inverted porosity in both cases (GA and PSO).

From the analysis of Figs. 6 and 7, one can notice that the low impedance zone found in the inverted impedance section also shows a very high porosity zone. This anomalous zone is already interpreted in the composite trace as well as well-log data between 1040 to 1065ms two-way travel time. This anomalous zone is characterized as a reservoir (sand channel). Additionally, we have shown inverted impedance and porosity using a standard inversion technique such as model-based inversion (MBI) in Fig. 8. MBI employs the least squares method, a local optimization approach that converges faster than global optimization methods. However, MBI’s performance is highly dependent on the accuracy of the initial model, if the initial model is inaccurate, MBI may not reach the global minimum, resulting in a less accurate subsurface earth model. In Fig. 8, the anomalous zone exhibits patches of low impedance and high porosity that are not uniform, lacking continuous definition. In contrast, global optimization techniques present the low impedance and high porosity zone more continuously.

For the quality check, the inverted synthetic is generated from the inverted impedance and porosity using the forward modeling technique and compared with Blackfoot seismic data. Figure 9 compares and presents Blackfoot seismic and replicated synthetic data. Figure 9 is divided into 4 panels, the first compares Blackfoot seismic to replicated synthetic seismic generated by inverted impedance using a genetic algorithm whereas the second panel compares seismic and inverted synthetic estimated from particle swarm optimization. Both curves (in the case of GA and PSO), match with each other very well with a very high correlation of 0.90 and 0.99, respectively. The third panel compares the seismic section with inverted synthetic derived from inverted porosity from GA and the fourth panel compares seismic data with inverted synthetic derived from the porosity section estimated using the PSO technique. These two seismic sections (in the case of GA and PSO) match with each other very well and the correlation coefficient is estimated to be 0.87 and 0.92, respectively. These qualitative and quantitative evaluations demonstrate how well the algorithm performs in this scenario.

The first and second panel compares Blackfoot seismic and reproduced synthetic sections from the inverted impedance estimated using GA and PSO, respectively. The third and fourth panel compares Blackfoot seismic and reproduced synthetic sections from the inverted porosity estimated using GA and PSO, respectively.

The GA and PSO optimization involves error minimization between observed (seismic) data and modeled (synthetic) data. The variation of error with iteration number is presented in Fig. 10. The average error decreases from 1.0 to 0.8 when the genetic algorithm is used, whereas it reaches 0.3 when particle swarm optimization is used. From the figure, one can notice that the error decreases exponentially and major error decreases in between 1-100 iterations in both the cases (GA and PSO). The analysis also shows that the error minimization is fast and the resolution of the inverted section estimated from PSO is better in comparison with GA.

The time required to perform the optimization procedure relies on the complexity of the geological model, the amount of data, and the algorithm utilized for seismic inversion. As a result, making optimal use of time, memory, and computer resources is critical to ensuring that the optimization process is completed in a fair amount of time. Figure 11 compares the convergence time of the genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization for synthetic as well as real data inversion cases. From the figure, it can be noticed that the PSO is less time-consuming as compared with GA in both cases. Using a PC(Personal Computer) with \(11th\,\, Gen\,\, Intel(R)\,\, Core(TM)\,\, i7-11700 @ 2.50GHz\, 2.50 GHz\), the convergence time of GA is 670680sec. whereas the PSO takes 356400sec. to invert a total of 3240 traces. This indicates \(88\%\) less convergence time of PSO as compared with GA.

An attempt was made to juxtapose the estimated impedance and porosity section with the findings presented by Maurya and Singh (2018), revealing a striking similarity between both sets of results. The study also calculated an anomalous zone with a two-way travel time of 1040–1065 ms and an extremely low acoustic impedance as well as a high porosity zone, which is likewise determined in the current investigation, and validated the results. Maurya and Singh, 2018 utilized the local optimization technique whereas the current study uses the global optimization technique which is proven to be a very powerful tool to minimize error and produces very high-resolution subsurface information that can not be retrieved using local optimization techniques.

Conclusions

Modeling and reservoir characterization are thought to be efficient ways to reduce subsurface uncertainty and improve reservoir prediction accuracy. In this study, qualitative as well as quantitative reservoir characterization has been performed using seismic inversion based on global optimization of algorithms such as genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization. These global optimizations algorithms are not so common as they need high computing and expertise to implement but are very powerful tools to get very high-resolution subsurface information. This study demonstrated that if prior information (well log) is included in these inversion methods, it can reduce convergence time and generate very high-resolution subsurface information. An algorithm of seismic inversion based on PSO and GA is presented in this study and tested with synthetic as well as real data. In synthetic data, the inverted impedance trace follows the trend of real impedance very well for GA and PSO-based inversion. The correlation coefficient is 0.993 and 0.986 have been achieved from GA and PSO inversion, respectively. The error variation with the iteration of particle swarm optimization is substantially lower than that of genetic algorithms. In real data, the inverted impedance and porosity show very high-resolution subsurface information in both cases (GA and PSO), with impedance variation from 6000 to 16,000 \(m/s *g/cc\) and porosity from 1 to 30%. The interpretation of inverted sections depicts a low impedance (6000–8500 \(m/s*g/cc\)) and high porosity (>20%) anomaly in the time interval 1040–1065 ms two-way travel time. This anomalous zone is also interpreted in well-log data and characterized as a reservoir (sand channel). The fitness error in this inversion process decreases from 1 to 0.88 with GA optimization after 400 iterations as opposed to 1 to 0.25 using PSO. The convergence time for PSO optimization is 356,400 s, but the convergence time for GA is 670,680 s, demonstrating that the former takes 88% longer to reach convergence.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from https://www.geosoftware.com/ but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the author (S.P. Maurya) upon reasonable request and with permission from https://www.geosoftware.com/.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available at: https://github.com/ravigeop/Global-optimization-GA-and-PSO-.git.

References

Li, X.-Y. & Zhang, Y.-G. Seismic reservoir characterization: how can multicomponent data help?. Journal of Geophysics and Engineering 8, 123–141 (2011).

Pendrel, J. Seismic inversion-the best tool for reservoir characterization. CSEG Recorder 26, 18–24 (2001).

Guo, Q., Luo, C. & Grana, D. Bayesian linearized rock-physics amplitude-variation-with-offset inversion for petrophysical and pore-geometry parameters in carbonate reservoirs. Geophysics 88, MR273–MR287 (2023).

Luo, C., Ba, J. & Guo, Q. Probabilistic seismic petrophysical inversion with statistical double-porosity biot-rayleigh model. Geophysics 88, M157–M171 (2023).

Krebs, J. R. et al. Fast full-wavefield seismic inversion using encoded sources. Geophysics 74, WCC177–WCC188 (2009).

Maurya, S., Singh, K., Kumar, A. & Singh, N. Reservoir characterization using post-stack seismic inversion techniques based on real coded genetic algorithm. Jour. of Geophysics 39 (2018).

Sokolov, A., Schulte, B., Shalaby, H. & van der Molen, M. Seismic inversion for reservoir characterization. In Applied techniques to integrated oil and gas reservoir characterization, 329–351 (Elsevier, 2021).

Schuster, G. T. Seismic inversion (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2017).

Russell, B. H. Introduction to seismic inversion methods. 2 (SEG Books, 1988).

Veeken, P., Silva, D. & M. Seismic inversion methods and some of their constraints. First break 22 (2004).

Jiang, M. & Spikes, K. T. Rock-physics and seismic-inversion based reservoir characterization of the haynesville shale. Journal of Geophysics and Engineering 13, 220–233 (2016).

Maurya, S., Singh, N. & Singh, K. H. Seismic inversion methods: a practical approach, vol. 1 (Springer, 2020).

Kennedy, J. Bare bones particle swarms. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium. SIS’03 (Cat. No. 03EX706), 80–87 (IEEE, 2003).

Fernandez Martinez, J. L., Mukerji, T., Garcia Gonzalo, E. & Suman, A. Reservoir characterization and inversion uncertainty via a family of particle swarm optimizers. Geophysics 77, M1–M16 (2012).

Yang, H. et al. Particle swarm optimization and its application to seismic inversion of igneous rocks. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 27, 349–357 (2017).

Shaw, R. & Srivastava, S. Particle swarm optimization: A new tool to invert geophysical data. Geophysics 72, F75–F83 (2007).

Poormirzaee, R., Moghadam, R. H. & Zarean, A. Inversion seismic refraction data using particle swarm optimization: a case study of tabriz, iran. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 8, 5981–5989 (2015).

Artun, E. & Mohaghegh, S. Intelligent seismic inversion workflow for high-resolution reservoir characterization. Computers & geosciences 37, 143–157 (2011).

Fang, Z. & Yang, D. Inversion of reservoir porosity, saturation, and permeability based on a robust hybrid genetic algorithm. Geophysics 80, R265–R280 (2015).

Velez-Langs, O. Genetic algorithms in oil industry: An overview. Journal of petroleum Science and Engineering 47, 15–22 (2005).

Eiben, A. E., Aarts, E. H. & Van Hee, K. M. Global convergence of genetic algorithms: A markov chain analysis. In Parallel Problem Solving from Nature: 1st Workshop, PPSN I Dortmund, FRG, October 1–3, 1990 Proceedings 1, 3–12 (Springer, 1991).

Boschetti, F., Dentith, M. C. & List, R. D. Inversion of seismic refraction data using genetic algorithms. Geophysics 61, 1715–1727 (1996).

Mallick, S. Model-based inversion of amplitude-variations-with-offset data using a genetic algorithm. Geophysics 60, 939–954 (1995).

Mallick, S., Lauve, J., Ahmad, R., Patel, K. N. & Dobbs, S. L. Hybrid seismic inversion: A reconnaissance exploration tool. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 1999, 1386–1389 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 1999).

Padhi, A. et al. Prestack waveform inversion for the water-column velocity structure-the present state and the road ahead. In SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, SEG–2010 (SEG, 2010).

McCormack, M. D., Stoisits, R. F., MacAllister, D. J. & Crawford, K. D. Applications of genetic algorithms in exploration and production. The Leading Edge 18, 716–718 (1999).

Maurya, S. P., Singh, N. P. & Singh, K. H. Use of genetic algorithm in reservoir characterisation from seismic data: A case study. Journal of Earth System Science 128, 1–15 (2019).

Romero, C. & Carter, J. Using genetic algorithms for reservoir characterisation. Journal of Petroleum Science and engineering 31, 113–123 (2001).

Huang, G., Chen, X., Luo, C. & Li, X. Prestack waveform inversion by using an optimized linear inversion scheme. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 57, 5716–5728 (2019).

Li, Z.-H., Wang, Y.-F. & Yang, C.-C. A fast global optimization algorithm for regularized migration imaging. Chinese Journal of Geophysics 54, 367–374 (2011).

Yu, X. & Gen, M. Introduction to evolutionary algorithms (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Ding, K., Chen, Y., Wang, Y. & Tan, Y. Regional seismic waveform inversion using swarm intelligence algorithms. In 2015 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 1235–1241 (IEEE, 2015).

Poormirzaee, R. Comparison of pso and ga metaheuristic methods to invert rayleigh wave dispersion curves for vs estimation: a case study. Journal of Analytical and Numerical Methods in Mining Engineering 9, 77–88 (2019).

Verma, N. et al. Comparison of neural networks techniques to predict subsurface parameters based on seismic inversion: a machine learning approach. Earth Science Informatics 1–22 (2024).

Lawton, D. C., Stewart, R., Cordsen, A. & Hrycak, S. Design review of the blackfoot 3c–3d seismic program. The CREWES Project Research Report 8, 1 (1996).

Lu, H.-X. & Margrave, G. F. Reprocessing the blackfoot 3c–3d seismic data (Tech. Rep, CREWES Research Report, 1998).

Simin, V., Harrison, M. P. & Lorentz, G. A. Processing the blackfoot 3c–3d seismic survey. CREWES Res Rep 8, 39–1 (1996).

Moncayo, E., Tchegliakova, N. & Montes, L. Pre-stack seismic inversion based on a genetic algorithm: A case from the llanos basin (colombia) in the absence of well information. CT &F-Ciencia, Tecnología y Futuro 4, 5–20 (2012).

Cheng, J.-W., Zhang, F. & Li, X.-Y. Nonlinear amplitude inversion using a hybrid quantum genetic algorithm and the exact zoeppritz equation. Petroleum Science 19, 1048–1064 (2022).

Pedersen, J. M., Vestergaard, P. D. & Zimmerman, T. Simulated annealing-based seismic inversion. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 1991, 941–944 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 1991).

Sen, M. K. & Stoffa, P. L. Global optimization methods in geophysical inversion (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Aleardi, M. & Mazzotti, A. 1d elastic full-waveform inversion and uncertainty estimation by means of a hybrid genetic algorithm-gibbs sampler approach. Geophysical Prospecting 65, 64–85 (2017).

Eberhart, R. & Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on neural networks, vol. 4, 1942–1948 (Citeseer, 1995).

Guo, Q., Ba, J., Luo, C. & Xiao, S. Stability-enhanced prestack seismic inversion using hybrid orthogonal learning particle swarm optimization. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 192, 107313 (2020).

Yasin, Q., Sohail, G. M., Ding, Y., Ismail, A. & Du, Q. Estimation of petrophysical parameters from seismic inversion by combining particle swarm optimization and multilayer linear calculator. Natural Resources Research 29, 3291–3317 (2020).

Rasmussen, K. & Maver, K. Direct inversion for porosity of post stack seismic data. In SPE European 3-D Reservoir Modelling Conference, SPE–35509 (SPE, 1996).

Kumar, R., Das, B., Chatterjee, R. & Sain, K. A methodology of porosity estimation from inversion of post-stack seismic data. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 28, 356–364 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank GeoSoftware for providing Hampson Russell software, particularly Emerge, Strata, and Geoview. One of the authors, Dr. S.P. Maurya, expresses gratitude to the funding organizations UGC-BSR (M-14-0585) and IoE BHU (Dev. Scheme No. 6031B) for their financial assistance. In addition, we acknowledge the academic licenses for Matlab (2022b) and Norsar (full package), respectively, from www.mathworks.com and www.norsar.no respectively. This work couldn’t be done without their help. This study is also supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University with project number PSAU/2023/R/1444.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ravi Kant perform the experiment and analyzed results, S.P. Maurya, Anoop Kumar Tiwari and Ravi Kant developed methodology and code and K.H. Singh and Kottakkaran Sooppy Nisar verified results. Finally, Ravi Kant drafted manuscript and finalized by S.P. Maurya and K.H. Singh.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kant, R., Maurya, S.P., Singh, K.H. et al. Qualitative and quantitative reservoir characterization using seismic inversion based on particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithm: a comparative case study. Sci Rep 14, 22581 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72278-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72278-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A case study of reservoir characterization and modeling for tidal-dominated estuary reservoir in Ecuador

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A case study of optimal design and techno-economic analysis of an islanded AC microgrid

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Adaptive Control-based frequency control strategy for PV/ DEG/ battery power system during islanding conditions

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Development of seismic inversion methods based on hybrid optimization of simulated annealing and quasi-Newton methods to estimate acoustic impedance and porosity from post-stack seismic data

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2025)

-

A methodology for the mapping of acoustic impedance and porosity in the inter-well region using seismic inversion based on the Hooke and Jeeves algorithm

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2025)