Abstract

Antibacterial resistance requires an advanced strategy to increase the efficacy of current therapeutics in addition to the synthesis of new generations of antibiotics. In this study, copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) were green synthesized using Moringa oleifera root extract. CuO-NPs fabricated into a form of aspartic acid-ciprofloxacin-polyethylene glycol coated copper oxide-nanotherapeutics (CIP-PEG-CuO) to improve the antibacterial activity of NPs and the efficacy of the drug with controlled cytotoxicity. These NPs were charachterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), x-rays diffraction spectroscopy (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Antibacterial screening and bacterial chemotaxis investigations demonstrated that CIP-PEG-CuO NPs show enhanced antibacterial potential against Gram-positive and Gram-negative clinically isolated pathogenic bacterial strains as compared to CuO-NPs. In ex-vivo cytotoxicity CIP-PEG-CuO-nano-formulates revealed 88% viability of Baby Hamster Kidney 21 cell lines and 90% RBCs remained intact with nano-formulations during hemolysis assay. An in-vivo studies on animal models show that Staphylococcus aureus were eradicated by this newly developed formulate from the infected skin and showed wound-healing properties. By using specially designed nanoparticles that are engineered to precisely transport antimicrobial agents, these efficient nano-drug delivery systems can target localized infections, ensure targeted delivery, enhance efficacy through increased drug penetration through physical barriers, and reduce systemic side effects for more effective treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The major global threat to contemporary medicine and society is antibiotic resistance1. Numerous multidrug-resistant bacterial strains, including methicillin and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, continue to plague both developed and developing countries1,2. Over 700,000 people die each year as a result of diseases caused by bacteria resistant to antibiotics3. Many researchers and medical professionals are currently working to discover answers for this rapidly expanding issue4. Uncontrolled usage of antibiotics is a main problem for developing bacterial resistance5. Some resistance manners can be resolvable by the synthesis of new drugs but many of them are difficult to solve even with a new generation of antibiotics6. This encouraged the scientists to explore developmental strategies for astounded such resilient microbes7. Some antibiotics target specific cellular processes or structures within bacteria, hindering their growth or causing cell death8. Chemotaxis might guide bacteria to move towards nutrient ingredient concentration, especially towards aspartic acid, this movement can also lead some bacteria into regions with increased antibiotic concentrations, by increasing the local effectiveness of the drug against targeted bacteria9. This intricate interplay between bacterial movement and antibiotic concentration gradients can inadvertently increase the efficacy of antibiotics by influencing the exposure and survival of bacterial populations, which can have a potential impact on treatment outcomes.

Some bacteria become resistant to drugs by increasing cell membrane impermeability or the increasing efflux mechanism thus drug cannot penetrate the bacterial cells10. One such example is ciprofloxacin which target topoisomerase enzyme in the nucleus. Ciprofloxacin is used for the treatment of bacterial infections such as endocarditis, lower respiratory tract, gastrointestinal, skin and soft tissue, and urinary tract infections11. Several bacteria such as Salmonella typhi, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have shown a rise in resistance to ciprofloxacin. The raise of ciprofloxacin-resistant infections indicates the need for the development of novel pharmacological compounds and synergisms. So, it is necessary to develop a nano-drugs delivery systems to deliver a drug to particular site and bypass barriers. Nanoparticles of silver12, zinc13, copper oxides14, cobalt15, and many others have been used for the development of nano-drugs delivery vehicles16.

CuO-NPs are non-toxic and nano drug delivery systems based on CuO have shown promising results against different bacterial infections. Various chemical methods such as co-precipitation, solvothermal, pyrolysis and sonochemistry are used for the synthesis of CuO-NPs but these methods have several limitations such as long preparation time, consumption of large quantitities of reagents and production of hazardous wastes. Green synthesis of NPs using plant extracts as a reducing agent has gained much attention from researchers in recent years owing to its eco-friendly nature, low production cost, rapid preparation, sustainable, and friendly to the environment16,17. Several researchers have synthesized CuO-NPs by green synthesis approaches for different applications and achieved satisfactory results. Recently, CuO-NPs with a 60 nm average size were synthesized by employing extract from Parthenium hysterophorus as a reducing agent18. These CuO-NP were utilized for rifampicin degradation and efficiency as high as 98.43% was obtained. In another study, CuO-NPs were prepared by green synthesis method using extract of Ephedra Alata as a reducing agent and indicated antibacterial and antifungal activity alongwith photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Similarly CuO/MgO composite were synthesized by green synthesis approach using Opuntia monacantha extract and the developed nanocomposite indicating promising antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis and Candida albicans19.

There are some challenges while using metallic nanoparticles (M-NPs) and metal oxides nanoparticles (MO-NPs) in clinical setups such as cytotoxicity. MO-NPs are mostly positively charged which react with negatively charged proteins in human body and release toxic metals which can have adverse effect on human body. Similarly, these toxic M-NPs and MO-NPs produce reactive oxygen species, destabilize the protein structures and cause cell memberane damage. Consequently, M-NPs and MO-NPs need to be modified before human cells may use them as safe drug delivery systems. Different types of drugs may be loaded over the MO-NPs to deliver it to the specific target. Herein, CuO-NPs were capped with PEG to make the NPs biocompatible by reducing their surface charge and to attach ciprofloxacin to these NPs for delivery to the target20,21. PEG is hydrophilic and its coating over NPs creates a hydration layer which makes a steric barrier22. Thus, the nano-formulation is able to avoid interactions with nearby NPs and blood components, such as immunogenic cells, owing to intrinsic hindrance effect. The PEG covering on nanoparticles prevents the body's reticuloendothelial system (RES) from opsonizing, aggregating, and phagocytosing of nanoparticles. PEG-coated nanoparticles have an extensive drug holding and systematic release period owing to the lack of immunogenicity. Cuo-PEG's systemic release of drugs after a particular period of time helps to lyse bacterial cells and disrupt biofilm, which enhances drug absorption and penetration into the intended spot23,24. Although green synthesis approach have several advantages over chemical and physical synthesis methods but there are several factors which affect the quality of final nanomaterials such as selection of proper solvent or mixture of slovents for extraction, reaction time and size distribution of synthesized NPs.

Moringa oleifera which is abundantly found in the northwestern Pakistan is rich in nutritional and bioactive substances that provide it pharmacological qualities like anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, anti-diabetic, antioxidant, cardioprotective, and hepatoprotective benefits. Its possible uses in therapeutic and functional food preparations have been investigated by its incorporation into a range of goods, such as cakes, biscuits, and juices, to boost their nutritional content25. In the current study, Moringa oleifera was chosen for synthesis of CuO-NPs by green approach. The extraction was performed using suitable solvent according to solvent polarity index to extract enough quantities of phenolics which act as reducing agent in synthesis of nanoparticles from its salt. Unlike other studies where only metal or metal oxide nanoparticles were used for antibacterial activity or wounds healing, in this study, an Aspartic acid-CIP-PEG-CuO-nanotherapeutics were synthesized to improve the drug's controlled cytotoxicity and NPs' antibacterial activity. CuO-NP and CIP-PEG-CuO nano-formulate were used for the antibacterial screening and bacterial chemotaxis investigations against clinically isolated pathogenic bacterial stain, both Gram-positive and Gram-negative and the outcomes were compared.

Materials and methods

Materials

Copper acetate monohydrate, NaOH, PEG (6000), ciprofloxacin pure salt, DPPH and ethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA. Powdered moringa oleifera roots were bought from a Rawalpindi local market, Pakistan. BHK 21 cell line, RBCs (human), and saline (low ionic strength) were taken from a Research Center in Peshawar, Pakistan. The nutrient broth and ager were bought from Oxide, Hampshire, UK.

Collection of Moringa oleifera

3Preparation of extract

The extracts of Moringa oleifera were prepared according to the methods reported with some modifications26,27. The roots of Moringa oleifera were grinded to fine powder and 10 g were dispersed in 90 mL distilled water, 10 mL ethanol was added into it to inhibit any fungal or bacterial growth, and stirred for 4 h at 80 °C and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and filtrate was stored in an airtight container.

Green synthesis of CuO-NPs

Copper acetate monohydrate (6 g) was dispersed in 120 mL de-ionized water and added Moringa oleifera roots extract (200 mL) with stirring for 12 h at 60 ºC. The synthesized Cuo-NPs were collected, washed with de-mineralized water and dried at 50 ºC overnight28.

Fabrication of CuO-NPs

Surface modifications were performed of synthesized CuO-NPs with PEG and CIP loading by solvent diffusion method. PEG solution 20 mL (4 mmol) was added into the flask containing CuO-NPs (0.1g) dispersed in deionized water (10 mL) and sonicated for 15 min and stirred for 36 h under ultra-sonication, and then placed at 4 ºC for 12 h and centrifuged to obtain the green synthesized PEG-CuO NPs. To load ciprofloxacine on PEG coated CuO NPs, 10 mL CIP solution (0.010 M) was added to 50 mL PEG-CuO-NPs and mixed under continuous stirring for 24 h. The stirring was assisted with ultra-sonication to enhance the interaction between the antibiotic and the PEG-NPs29. The contents were washed with DW for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm to eliminate the extra suspended CIP and PEG. The CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs were dried and stored for further use.

Assay for drug release

The dialysis membrane was utilized to assess quantity of drug released with time. A partition was created between the working platform, by separating it into donor and recipient compartments. A dialysis membrane was positioned between these two sections. Subsequently, the donor compartment was filled with 4 mL of nano-therapeutic spray at a dosage of 10 mg/L. The recipient compartment was filled with a 12 mL phosphate buffer solution with a pH value of 7.5. A magnetic bar was inserted into the recipient chamber and revolved at a speed of 75 rpm at 37 °C. Specimens were extracted at pre-established time intervals. The initial sample was collected at time 0, followed by subsequent samples at 2–12 h. After each iteraction the sample was extracted from the recipient compartment and replaced with a new buffer. Absorbance was analyzed at 450 nm, drug release was calculated using the following Eq. (1) 30.

Formulation of nano-therapeutic

Green synthesized CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs were used for in-vivo experiments on wounds of mice skin to evaluate their potentials for controlling infection and wound healing. A spray was prepared for wound healing of mice skin using CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs, 5% ethanol, glycerin and L-aspartic acid. Ethanol act as a solvent, glycerin as a preservative, adhesive and moisturizing agent, L-aspartic acid as bacterial attractant to the site of infection and ciprofloxacine as an active ingredient to kill bacteria31,32. In a typical experiment, 10 µg/mL Gr-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs nano-formulates was dispersed in 5% ethanol and stirred for 2 h, sonicated and placed at –20 ºC in a refrigerator for 30 min. Then, 1 mL of glycerin and 1 mL of L-Aspartic acid were added to CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs and stirred for 2 h. The spray was stored at 4 ºC prior to HPLC analysis and in-vivo experiments on mice to examine its efficacy infected mice's skin to prevent infection and accelerate wound healing.

Characterization of CuO-NPs and CIP-PEG-CuO-nano-formulation

The nano-formulations were analyzed by an X-ray diffractometer (D/MAX 2550, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) to ascertain their crystalline character and crystal phase composition. Using (Cu Kα1 radiation, γ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 100 mA, wide-angle XRD was used to examine the diffraction in the range of 10–80 (2θ). The size and crystalline structure were estimated using the Scherrer equation. A Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (FT-IR Spectrum 100 spectrometer) was utilized to ascertain the functional groups of loaded medicines at 500–4000 cm−1 and of all synthesized nanomaterials. The examination of the shape and morphology was carried out using scanning electron microscopy. Prior to observation, 10 µL of the nanoparticle suspension was placed on a metal stub plating and coated with gold using sputtering machine. A scanning electron microscope (MIRA3-TESCAN) was used to capture the SEM images. Additionally, chemical composition of the nanoformulate and the copper concentration in it was measursed using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Shimadzu LC-20AD, HPLC system was used to determine L-aspartic acid and ciprofloxacin in nano-therapeutic material (CIP-PEG-CuO).

Bacterial strains

Bacterial strains of clinical source were used to determine antibacterial activity of the nanomaterials. Bacteria were identified using microscopy and biochemical caharacterization using API20E test array prior to their use in antibacterial assay.

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of CIP-PEG-CuO and CIP unloaded CuO-NPs checked by disc diffusion method33. Each strain's inoculation plate was supplemented with nanomaterial-coated discs after the bacteria strains were separately scrubbed onto nutrient agar plates. The plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37 ºC. The effectiveness of the nanomaterials was estimated by monitoring the zones of inhibition, and the outcomes greater than 11 mm were deemed sensitive and effective.

MIC and MBC determination

Effective nano-formulations were used for MIC determination by preparing four-fold dilution of nano-formulations as test samples with concentrations of (5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.6 µg/mL). Subsequently, 100 µL of cultured bacterial was added to each 96-well plate and incubated at 37 ºC for 24 h. The results were checked by visible antibacterial activity determination and verified by taking absorbance at 540 nm and by comparing with controls. MIC is the minimum concentration that shows a visible clear well, the results were interpreted by using a CLSI-based system24.

Biofilm assay

Biofilm inhibition

Using the biofilm inhibition experiment, the ability of the nano-formulates to stop bacterial cells from adhering at the beginning was examined. After adding 200 µL of nano-formulations (5 µg/mL) to the 96-well plate, four times sequential concentrations (0.6–5 µg/mL) were prepared. The well plate was additionally supplemented with the positive control (broth plus bacterial inoculum) and negative control (broth with only nutrients). Next, a bacterial inoculum of 10 µL was introduced into all wells except the negative control wells. Six hours were spent incubating the plate to promote early cell adhesion and biofilm generation. 100 µL of crystal violet dye (1%) was added to each well. Ultimately, 33% acetic acid was injected, and the colored intensity which indicates the production of biofilms was measured at 295 nm34 .

Biofilm destruction

The potential of nano-formulations to inhibit biofilm progression or destruction of pre-formed biofilms was investigated35. Each bacterial strain's 96-well plate was properly labeled and90 µL of nutrient broth and the inoculum of bacteria were put to the very first row, that was marked as the positive control. The subsequent rows of each specimen were supplemented with the same concentration of feeding broth and bacteria, and the plates were subsequently incubated in accordance with the formation of different dilutions. The following day, cultured wells were filled with samples (nano-formulations) of 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.6 µg/mL, and the plates were left to incubate for a full day. Subsequently, distilled water was used to wash the plates, and each well was filled with 125 µL of crystal violet dye before being incubated for an additional 15 min. After the well plates were cleaned, dried, and supplemented with 33% acetic acid, a microplate reader reading was obtained at 590 nm. The wells’ color intensity also reveals if biofilm formation or inhibition is present. Each effective nano-formulations were tested against those bacteria which showed effective results during initial antibacterial screening. Biofilm inhibition and destruction were not performed in the same plates, and each effective nano-formulation was tested against those bacteria which showed effective results during antibacterial assays and as well as in MIC/MBC.

Antibacterial mechanism determination of CuO-NPs and their nano-formulations

Anti-oxidant assay

Antioxidant activity of Gr-CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations was determined by a 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging study36. Oxides were produced by the reaction of DPPH with CuO NPs which causes the reduction of DPPH and turned from a deep violet to a yellow color. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm following a 30 min dark incubation. Equation (2) estimated the percentage of released oxides, and the control was also performed using a mixture of DPPH and ethanol solution.

where “% I” is percent inhibition while “Ablank” and “Asample” represent the absorbance of blank and sample analyzed respectively.

Assay for DNA release and protein leakage

The potency of nanomaterials was used to evaluate the release of DNA and proteins from the membranes of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, respectively37. The bacteria were cultivated in 100 mL of LB broth, 100 mL of CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations (10 µg/mL) were added to the mixture and incubated at 37 ºC at 125 rpm. Then, the culture was centrifuged at 4 ºC for 20 min and the supernatant was evaluated for DNA and proteins.

Bacterial chemotaxis

Bacterial chemotaxis such as E.coli toward the nano-therapeutic was assayed by measuring the number of organisms after passing through a capillary tube attached with bacterial attractant i.e., L-aspartic acid-CIP-PEG-CuO-Nano-therapeutic. The apparatus was divided into two parts, first, the donor compartment which consists of quantified bacterial suspension mixed into glycerol at pH 7.0, the pH was adjusted by using potassium phosphate buffer containing 10−3 M of EDTA38. The second part of the apparatus was the recipient compartment, both parts were linked with a capillary tube coated with nano-therapeutic agent (Fig. S1). During the assay, the bacterial suspension was allowed to move slowly (20 µL in 1 min) from the donor to the recipient compartment through the capillary tube at 37 ºC. Owing to the presence of a bacterial attractant (L-aspartic acid contained nano-therapeutic) in the capillary tube mostly bacteria accumulated in its inner side and minimum bacterial concentration was reached into the recipient compartment which was assessed by absorbance. A control was also run without containing L-aspartic acid containing nano-therapeutic. The results were concluded by calculating the optical density of both compartments' suspension, and live/dead ratio using fluorescence microscopy by staining with SYTO9 and propidium iodide of accumulated bacteria cells inside the capillary tube. The accumulated bacterial sample was stained with SYTO9 for 15 min and after an additional 15 min counterstaining with PI. The percentage of dead live/bacteria was calculated per 100 cell count. The green color indicates the integrity of the bacterial membrane which is a direct clue for alive cells, red color indicated dead bacterial due to red color PI staining of DNA. A clear reduction in SYTO9 staining was observed after binding of PI with the dead cells.

In-vitro cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity of CuO-NPs and nano-formulates

Baby Hamster Kidney cells 21 (BHK21) were utilized in the MTT assay to test the cytotoxicity of CuO-NPs and their nano-formulations39. The Baby Hamster kidney cells lines were cultivated on Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) in 96-well plates. After that, 1 × 105 cells were distributed into each well, and the CO2 incubator was set to 37 ºC for 24 h. With PBS serving as the study's control and Celecoxib serving as the PC (positive control), the live BMGE cells (1 × 105) were treated with nano-formulations at escalating concentrations (5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.6 µg/mL) and incubated at 37 ºC for 24 h. After the incubation period, 10 µL of MTT solution made in PBS 1X and 100 µL DMEM were shaken to replace the old DMEM. Four more hours were spent incubating the 96-well plates. The formazan crystals in the wells were eventually dissolved with 0.1 mL of DMSO solution, and the optical density (OD) of the wells containing MTT formazan—which served as an internal control and BHK cells treated with nano-formulations at different concentrations were calculated at 570 nm and 620 nm, respectively. With the use of the provided standard equation, the viability percentage was determined.

Hemolysis assay

The hemolysis assay was measured using the test tube method. The sedimented RBCs were then 20% diluted with LISS and utilized in the experiment. A fresh glass test tube was filled with one drop of cleaned RBCs and two drops of low ionic strength solution (LISS). After that, 100 µL of a 2.5 µg concentrated nano-formulation was added, gently stirred, covered with aluminum foil, and incubated for an additional night at 37 ºC. After 24 h, the reaction was centrifuged for 30 s at 3500 rpm. The results showed that the positive reaction had a cherry red color in the supernatant, while the negative reaction had a colorless appearance. Furthermore, two controls were run: a positive control (D/W + RBCs) that looked cherry red and a negative reference (LISS + RBCs) that looked colorless in the supernatant. Using a microplate reader, the absorbance values of the supernatant were measured at 570 nm. The following Eq. (4) was used to calculate the proportion of hemolysis in red blood cells:

In-vivo studies on animal model

A 30 g weighted albino mouse model was used for the in-vivo tests. First, Xylocaine was applied to numb the skin after hair removing gel was used. Next, a surgical blade was used to create a 16 mm long wound. The studies were divided into two groups: treatment I looked at how a topical drug affected the healing and damage of wounds, while treatment II looked at getting rid of skin infections. Two mice were used in the first wound healing experiment. The first mouse's wound was cleaned with disinfectant, and a topical agent based on green synthesized CIP-PEG-CuO-aspartic acid was thrust onto it every day while each contained 500 µL nano-therapeutic (10 mg). The second mouse received no topical treatment; instead, their wounds were monitored for the following 10 days. The identical experimental design was employed in Treatment II, but it was modified to manage the infection. In this instance, Staphylococcus aureus was applied to the site. Following the confirmation of infection, a topical agent based on CIP-PEG-CuO-aspartic acid was applied by thrusting onto the wound. Every day, the same dose was consistently administered, and wound length contraction was used to track the healing process. Swab sticks were used to gather random samples, which were then cultured to determine if the bacteria had been completely eradicated from the infection site. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used to prepare skin samples for histological analysis at the conclusion of the in-vivo trial. This allowed researchers to assess the morphological characteristics of the healed skin in the experimental and control groups.

Statistical analysis

Three separate runs of each assay were performed, and the results are presented as the mean standard deviation. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference (LSD) were used to further examine the means at the probability threshold of p < 0.05. SAS statistical software, version 9.1.2, was used to analyze all of the data (SAS, 2004).

Results & discussions

Characterization

FTIR analysis

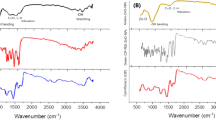

The FTIR analysis of Gr-CuO-NPs, CIP, and conjugation of ciprofloxacin is shown in (Fig. S2). An orange line representing FTIR spectra of CuO-NPs in which characteristic peaks at 3550 cm−1, 3350 cm−1, 2450 cm−1, 1090 cm−1, and 800 cm−1. The FTIR spectra of CuO NPs reported in previously published work have also obtained similar peaks as obtained in the current study40,41. Red line indicating the FTIR spectra of CIP with representative peaks at 2700 cm−1, 2470 cm−1, 1650 cm−1, 1470 cm−1, and 1200 cm−1. A black line indicates successful attachement of CIP and PEG on CuO-NPs by representing characteristic peaks at 3560 cm−1, 1650 cm−1, 1470 cm−1, 1200 cm−1, and 1090 cm−1. The results were comparable with previously reported work17. The capping with CIP-PEG serves a dual purpose, it enhances the stability and dispersibility of NPs in various solvents or biological media, significant for applications in drug delivery and biomedical fields, while also enabling the nanoparticles to exhibit inherent antibacterial properties attributed to both the NPs and ciprofloxacin components.

XRD analysis

XRD analysis was used to check the crystalline structure of CuO-NPs and their nano-formulations. The XRD spectra of CuO-NPs are shown in Fig. 1. The red line indicating the XRD peaks of CuO-NPs at 2θ = 34.1193°, 35.6532°, 38.3012°, 46.5312°, 49.5413°, 52.7401°, 58.4561°, 61.6231°, 66.2301°, 69.0015°, 72.2191° and 75.1201°, correspond to the (110), (002), (111), (112), (202), (020), (202), (113) (311), 113), (220), and (311) crystal planes with hexagonal structure, these results are comparable with other studies42,43. The peaks were in same range for CIP-PEG-CuO-nano formulation but with high intensity due to CIP-PEG capping. The average particle size of the NPs was calculated by using the Scherrer equation. The size of the green synthesized CuO-NPs calculated from the XRD spectrum was 69 nm and the size of CIP-PEG-CuO-nano formulation was 243 nm.

SEM analysis

The surface structure and morphological properties of the CuO-NPs were observed by SEM analysis in order to facilitate further characterization. According to the results of the current investigation, the greenly produced CuO-NPs are spherical agglomerates of nanocrystallites43. The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) results show an adequate content of copper in synthesized NPs, which indicated their purity as shown in (Fig. 2a, b). The NPs rely on X-ray signals emitted when high-energy electrons interact with them. The higher concentration of NPs ensured a stronger signal, which improved the accuracy and sensitivity of elemental composition during analysis. EDS detected copper from individual samples and expressed them as absorption peaks. On the other hand, some other signals at low amplitudes, including carbon, oxygen, chlorine, and silicon were also detected in synthesized nanomaterials.

HPLC analysis

The HPLC analysis of green synthesized CIP-PEG-CuO-aspartic acid was carried out using C18 column and methanol:water (50:50 v/v) as mobile phase. The results in Fig. S3 show a peaks at 6.13 min and 9.41 min representing ciprofloxacin and L-aspartic acid respectively. The HPLC results confirmed the presence of CIP and aspartic acid in the nanoformulation. The retention times of pure CIP and L-aspertic acid was measured as a reference standard to compare the retention times of each analyte with the chromatogram of nanoformulation. Similar retention pattern for these selected analytes were obtained in other studies reported in literature17,44. The HPLC chromatogram of CIP-PEG-CuO-aspartic acid is shown in (Fig. S3) and the results are summarized in Table 1.

Drug release profile from CIP-CuO-NPs and CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs

CIP-CuO-NPs showed a drug release of 92.6 + 1.2% after 12 h, whereas CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs showed 86.5 + 1.8% drug (CIP) release. The findings demonstrated that PEG-uncoated CuO-NPs released CIP more quickly than PEG-coated CuO-NPs, which released CIP in a controlled and long-lasting manner.

Antibacterial studies

Bacterial isolates were biochemically identified by API20E test panel through microscopy i.e. Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E.coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae were identified as Gram-negative while Staph aureus, MRSA, and Enterococcus faecalis were identified as Gram-Positive cocci. The antibacterial vulnerability patterns of CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations were confirmed by the disc diffusion method and the results are presented in Fig. 3. The results showed enhanced antibacterial susceptibility with Green-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs against clinically isolated bacterial pathogens as compared to simple CuO-NPs (Fig. 3). Silimilarly, antibacterial activity of the designed nanoforumulation and the zone of inhibition in plates are shown in Fig. 4. Statistical analysis indicated same variance within groups. Table S1 shows the results of ANOVA of zone inhibition. Similar to our findings previous reports on comparison of green synthesized silver nanoparticles indicated higher antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli as compared to ciprofloxacin alone indicating the possibility of green synthesized silver nanoparticles to be used in various formulations45,46.

MIC & MBC determination

Effective Nanoformulates were further subjected to MIC and MBC. The results disclosed that MIC of Green-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs was 2.5 µg/mL against Staph aureus, MRSA, Enterococcus faecalis, Salmonella typhi, and 5 µg/mL against Klebsiella pneumoniae, E.coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This proposed that Green-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs are an efficient nano-antimicrobial agent that is effective in a broad range. In order to determine the minimal bactericidal concentration, the last clearly visible well was cultured; this resulted in no growth on the nutrient agar plate. Minimum bactericidal concentration against Salmonella typhi, Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, Enterococcus faecalis, was recorded as 5 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL against E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Similar trend was observed by Rodriguez-Melcon et al.47 using three bioacids and twelve antibiotics against eight strains of Listeria monocytogenes. In another study Green-CuO-nanoformulation indicated MIC contrary to a our study where CuO-NPs showed 12.5 µg/ml as an effective concentration48. The difference may be due to involvement of Moringa oleifera that has several medicinal uses to treat skin problems, gastric ulcers, bronchitis, ear and eye complaints, and urinary infections. It is known for its exceptional properties like anti-oxidant capabilities, anti-asthmatic activity, potential antimicrobial activity, strong wound-healing effect, and high anti-inflammatory ability. Minimum effective dose concentration is very important with reduced side effects of NPs, to set their value concentrations for biomedical applications. Low-dose effective concentrations of CIP-PEG-NPs allow targeted delivery of antibiotics directly to infection sites, minimizing systemic exposure and thereby reducing potential side effects. The incorporation of NPs might offer additional antimicrobial properties, synergistically enhancing the antibiotic effect of ciprofloxacin against certain infections35.

Biofilm assay

The effects of nanoformulates on biofilm inhibition and destruction were examined according to the protocol presented by Haney et al.34. The results found nano-formulates have an anti-biofilm effect against which inhibited biofilm formation at 2.5 µg/mL concentration for Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhi, Enterococcus faecalis and MRSA, at 5 µg/mL Pseudomonas aeruginosa E.coli, and Klebsiella pneumonia (Fig. 5A). While biofilm destruction was observed at 5 µg/mL concentration against, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhi, MRSA, and Enterococcus faecalis, and 10 µg/mL for Klebsiella pneumoniae, E.coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 5B). A single factor ANOVA for biofilm inhibition and biofilm destruction assays of the developed nanomaterial is given in Table S2 and S3 respectively. The variance for six counts for biofilm inhibition and biofilm destruction assays were found to be 0.00457 and 0.00432 respectively. Similar trend was observed by other researchers for metal oxide NPs against bacterial biofilm49.

Evaluation of antibacterial mechanism of CuO-NPs and their nano-formulations

Antioxidant assay

The Antioxidant observation explored the individual CuO-NPs exhibited oxidation with higher free radical scavering capability as compared to nanoformulations, while the control test was stable in the same conditions without changes in violet color (Fig. 6 and Table S4). The variance for six counts for antioxidant assay were found to be 180.5. The calculated IC50 of Gr-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs was 107 µg/mL, whereas Gr-CuO-NPs revealed 121 µg/mL IC50 respectively. In a relevant study 79.8 µg/mL concentration of CuO-NPs weas observed as IC5024. CuO-NPs could potentially help manage oxidative stress in the host, which create a less favorable environment for bacterial survival. Antioxidant property of CuO based nanoformulations neutralize free radicals that can cause oxidative stress in both living organisms and microbial cells. This oxidative stress can damage cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA. By neutralizing these radicals, antioxidants may help protect the host cells from oxidative damage or potentially affect the bacteria's oxidative stress response.

Assay for protein leakage and DNA release

Protein leakage and DNA release studies of CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations were determined by their effects on Staphylococcus aureus representatively as gram-positive and Salmonella typhus as gram-negative bacteria. The results show that bacteria treated with CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs have released protein and DNA more than bacteria treated with simple CuO-NPs and negative control (Fig. 7A & B). A single factor ANOVA for thos assay is given in Table S5. The variance for six counts for antoxidant assay were found to be 0.08. In the form of nanoformulations, the NPs target the membranal protein structure, where they disturb the physical, and functional features of the membrane and create pores, which cause protein and DNA release from the bacterial cell. Membrane damage due to nanoformulations also leads to protein leakage while NPs-CIP may interact with topoisomerase and can cause the disintegration of DNA into segments.

(A) DNA release study from bacteria with the treatment of CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations, (B) protein leakage study from bacteria with the treatment of CuO-NPs and their nanoformulations. The mean values with standard deviation were evaluated. The significant difference (p < 0.05) measured by one-way ANOVA between all tested nanomaterials.

Bacterial chemotaxis

The bacterial chemotaxis was evaluated by measuring optical density of the donor, recipient compartment, and the capillary tube of the apparatus to observe the attraction of bacteria towards the L-aspartic acid-CIP-PEG-CuO-Nanaotherapeutics. The results indicated that bacteria could not migrate properly in the recipient compartment, as their concentration was present in the donor compartment of the apparatus. It also has been observed that optical density in the capillary tube was more than in both compartments, which was due to the accumulation of bacteria in the tube This indicated that bacteria attracted and stayed in the capillary tube due to L-aspartic acid attached nano-therapeutic agent as shown in Fig. 8(A). During live and dead cells assessment only 22% of bacterial cells were found live in the capillary tube. The nano-therapeutic feasibility for bacterial attraction facilitates the nano-drug delivery system to trap the bacteria towards antimicrobial agents and enhance their targeting in the therapeutic environment. In the control assay, the equal concentration was measured in all compartments and there was no accumulation observed in the capillary tube (Fig. 8 B)50.

Ex-vivo cytotoxicity

Cytotoxic effects of CuO-NPs and nano-formulates on baby hamster kidney 21 cells lines (BHK21)

The cytotoxic potential of green synthesized CuO-NPs and Gr-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs was analyzed at 0.6–5 µg/mL on primary cultures of proliferating BHK21. After treatment with synthesized nanomaterials, BHK cells were seen to be functionally viable and proliferating in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment of BHK cells with green synthesized CuO-NPs showed 75% viable cells with 5 µg/mL concentration. The BHK cells viability was 88% and the proliferation of cells was observed with 5 µg/mL of Gr-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs. Figure 9 shows the viability pattern utilizing various amounts of produced nanoformulations. This work established the synthesized nanoformulation’s profound biocompatibility with BHK cells by showing an excellent viability pattern and a regulated cytotoxic profile compared to single CuO nanoparticles. Similar trend was observed by Kaningini et al.51 using green synthesized CuO-NPs using extracts of Athrixia phylicoides.

Ex-vivo cytotoxicity of green synthesized CuO-NPs and Gr-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs on BHK21; (A) (negative control), (B) (positive control); (C) (G-CIP-PEG-Cuo-NPs), (D) ( G-CuO-Nps) E (PEG), F (CIP). The mean values with standard deviation were evaluated. The significant difference (p < 0.05) measured by one-way ANOVA between all tested nanomaterials.

Hemolysis assay

Nanoparticles can come in contact with blood tissue directly or indirectly, and it has the ability to transfer them to other cells, tissues, and organs. This makes research on the toxicity of blood, particularly erythrocytes, crucial. Hemolytic activity of Gr-CuO-NPs and their nano-formulations at 5 µg/mL concentration was measured to investigate the bio-safety with human RBCs. Using a microplate reader, the absorbance values of the supernatant were measured at 570 nm once the hemolysis reaction was completed. As seen in (Fig. S4), the percentage of hemolysis in RBCs was ascertained. Positive control showed 80% of hemolysis, negative control with no hemolysis, green synthesized CuO-NPs showed 31% hemolysis while Green-CIP-PEG-CuO-nanoformulations 10% hemolysis. In another study, RBCs of freshwater fish Carassius auratus were treated with CuO-NPs. In the results, 40 µg/ml of concentrated NPs showed hemolytic effects52. Reported data indicated that metallic oxide NPs have hemolytic effects, while synthesized nanoformulations revealed minimized effects on RBCs.

In-vivo studies on animal model

The treatment-1 model was used to assess whether Gr-CuO-NPs-based nanotherapeutics cure wounds or cause harm to the skin following standard protocol53,54. In comparison to the control group, the results showed a rapid healing process, with 83.1% of the wounds shrinking on day 10 as a result of the healing process (Fig. 10A & B). To assess the removal of skin infection, the treatment II model was processed. In comparison to the control group, it has been found that green produced CuO-NPs-based nano-therapeutics may kill Staphylococcus aureus on infected skin and promote 81.5% of wound healing on day 10 (Fig. 11A & B and Table 2). Physical characteristics included normal hair growth in the vicinity of the infected wound following the application of Green-CIP-PEG-CuO nanotherapeutic; additionally, no abnormalities were noted in the behavior of the experimental mice models or in the texture of their wounded skin. These findings suggest that the infection was removed from the target site by the synthesised nanotherapeutic without causing any toxic side effects when applied topically. Our findings are in accordance to Song et al.55 who successfully synthesized cephradine (Ceph) encapsulated chitosan and poly (3-hydroxy butyric acid-co-3-hydroxy valeric acid, (PHBV)) hybrid nanofibers (Ceph-CHP NFs) to prevent the bacterial growth and trigger the wound healing process for post surgical applications. The results demonstrated controlled drug release with a constant rate with enhanced efficacy of Ceph-CHP NFs against MRSA clinical isolates. Additionaly the rsults of in vitro assay exhibited no visible cytotoxicity against keratinocytes.

Recently the antimicrobial characteristics of copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NPs) were evaluated when administered externally and investigated the influence of CuS nanoparticles on the recovery process of infected wounds in a rat model56. Our results in accordance to previous results indicated that CuO nanoparticles exhibit antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, these nanotheraputics have the potential to reduce the occurrence of bacterial colonization and enhance wound healing by facilitating re-epithelialization and collagen deposition. In addition, CuO nanoparticles can sustain the continuous release of Cu2+ and hinder the growth of Staphylococcus aureus by inducing lipid peroxidation.

Histological analysis of skin

Microscopic examination was performed of wound healing and infection control experimental skin tissues by using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining on day 10. The tissue of both experimental groups indicated normal regeneration of skin layers and growth of hair follicles after treatment with green synthesized Aspartic acid-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs based nanotherapeutics. There was no abnormality observed in the cell arrangement or the nuclear structure in both experimental tissues. In the control group of wound healing experimental tissues noted with slow but normal tissue regeneration process as compared to experimental tests. The microscopic examination of tissues in the control group of infection recovery revealed the results with irregularity in the cell arrangement of skin layers and neutrophil infiltration was noted this can be due to improper eradication of infectious agents from untreated wounds (Fig. 12). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on day 10 and the skin tissues were observed under microscope to check the progress of wound healing and infection control. After treatment with Green-CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs based nanotherapeutics, the tissue of both experimental groups showed normal skin layer regeneration and hair follicle growth. In both experimental tissues, there were no abnormality in the nuclear structure or cell organization. In contrast to the experimental testing, the tissues in the control group showed a sluggish but normal tissue regeneration process. Microscopic analysis of the tissues in the infection recovery control group showed abnormalities in the skin layer cell organization and neutrophil infiltration, which may have resulted from inadequate removal of infectious bacterial from open wounds (Fig. 12).

H & E microscopy of skin tissues (40X), (A) Wound healing after treatment with CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs at 40X, (B) Control model of wound healing without treatment, (C) Infection recovery experimental skin tissue after treatment with CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs, (D) Control model of infection recovery without treatment.

CuO-CIP nanoparticles serve as an effective drug delivery system that enable controlled release of therapeutic compounds. These types of formulations can be designed with the encapsulation of antibiotics or anticancer agents and deliver them specifically to the desired site of action in the body. By minimizing the direct exposure of healthy tissues to the drug or NPs, this delivery method lowers side effects and increases the overall efficacy of the medication57. CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs can protect the encapsulated drug from degradation and premature release, enhancing its stability during storage and transportation. This prolongs the medication's shelf life and ensures that the medication maintains its potency until it reaches its target spot. In a study, another similar study, CuO-NPs was combined with antibiotic and showed effective results against E. coli, and also observed their mechanism with increased cytoplasmic leakage58. Target cell surface receptors can be selectively recognized and bound to by ligands or antibodies to functionalize the nanoparticles. This active targeting further enhances the specificity and efficiency of drug delivery to specific cell types, such as cancer cells, while sparing healthy cells. CuO-NPs are known to have average cytotoxic effects compared to some other metal-based nanoparticles. Green synthesis or PEG-CuO nanoparticles, can reduce the risk of harm to healthy cells and tissues, which is crucial for maintaining patient safety during treatment59,60. PEG has a negative charge and can be coated on NPs easily, it can withhold any drug that has a positive charge such as CIP. The NPs' surface positive charge has been reduced by PEG capping, which also makes it easier for CIP and CuO-NPs to bind to each other. This reduces the NPs' cytotoxic effects, as shown by viability tests on BHK21 cell lines and observations of the integrity of the RBCs during hemolysis assays. The results of the study demonstrate the efficacy of the CIP-PEG-CuO-NPs functionalized system in generating responses against clinically isolated bacteria. The primary mechanism here is the collapse of the bacterial membrane owing to the generation of free electrons and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which combine to create holes in the structures of the membrane61. This facilitates CIP to enter the bacterial cell, thereby, achieving their target and inhibiting bacterial growth. When ROS combine with the roughness of native CuO-NPs of CIP-CuO, they cause damage to the bacterial cell membrane. This makes it possible for the antibiotic-conjugated CIP to enter the bacteria and disrupt the cell, which cannot be done with the antibiotic alone when drug penetration is inhibited by biofilm formation or the bacterial membrane impermeability. To enhance the antibacterial capability bacterial chemotaxis can also be beneficial in their movement towards the nano-antimicrobial agents. Bacterial cells such as E.coli have chemotaxis receptors for Serine and Aspartic acids and other amino acids on the membrane which facilitate sensation and movement towards these nutrient ingredients62,63. The use of amino acid coated on nanomaterial can be used as a trap for the bacteria, which can be useful to increase the efficacy of antibacterial agents. This type of novel modification of CuO-NPs allows for targeted delivery of ciprofloxacin directly to the site of application. This targeted delivery ensures a higher concentration of the drug at the desired location, with improved efficacy and reduced potential for systemic side effects. By applying CIP-conjugated-PEG-CuO-NPs topically, the drug is primarily confined to the skin or specific soft tissue surfaces. This localized treatment is especially beneficial for skin infections or infections in other accessible tissues, as it minimizes unnecessary exposure to the rest of the body. They can protect the encapsulated drug from degradation, providing stability during storage and application. This helps maintain the potency of ciprofloxacin and extends its shelf life, which can be engineered to release gradually over time64. The localized and targeted delivery of ciprofloxacin via CuO-NPs helped to minimize the exposure of bacteria to sublethal concentrations of the drug. And can enhance the penetration of ciprofloxacin through the skin's outermost layer (stratum corneum), increasing drug absorption and bioavailability at the site of infection65,66. This opens up possibilities for combination therapy, where different drugs can work synergistically to improve treatment outcomes. Besides their antimicrobial properties, CuO-NPs have been studied for their wound-healing capabilities, promoting tissue regeneration and reducing inflammation. When combined with ciprofloxacin, they may have additional benefits in managing infected wounds.

Conclusion

CuO-PEG-CIP-Aspartic acid nanotherapeutics were created using NPs in order to improve the drug's regulated cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity. Antibacterial screening and bacterial chemotaxis investigations shown enhanced antibacterial capacity in comparison to single NPs against pathogenic strains of bacteria (both Gram-positive and Gram-negative). BHK21 cell line had 88% viability in ex-vivo cytotoxicity CIP-PEG-CuO nano-formulates, and 90% of RBCs were intact throughout the hemolysis experiment. They demonstrated wound-healing abilities and eliminated Staphylococcus aureus from contaminated skin during in-vivo experiments. By using specially designed nanoparticles that are engineered to precisely transport antimicrobial agents, these efficient nano-drug delivery systems can target localized infections, ensure targeted delivery, enhance efficacy through increased drug penetration through physical barriers, and reduce systemic side effects for more effective treatment. Green synthesized-CIP-PEG-CuO-nanoformulation showed a broad range of effectiveness against common pathogenic bacteria with increased efficacy of CIP in a controlled manner which offered targeted drug delivery directly to the infection site, maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic exposure and reducing the likelihood of antibiotic resistance development. These types of drug delivery systems can be used in the future to coat materials used for the synthesis of dental and other implants to eradicate chances of the development of biofilms on their surface and can give long-term protection against infections. Target moieties on the surface of drug-PEG conjugated NPs should be introduced to enhance specificity for bacterial cells. Ligands or amino acids that can selectively bind to bacterial receptors or cell wall components can improve the nanoparticles' ability to target and penetrate bacterial biofilms.

Data availability

The data is provided within the manuscript while additional data are provided in the supplementary information file.

References

Church, N. A. & McKillip, J. L. Antibiotic resistance crisis: Challenges and imperatives. Biologia 76, 1535–1550 (2021).

Larsson, D. & Flach, C.-F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 257–269 (2022).

Mancuso, G., Midiri, A., Gerace, E. & Biondo, C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: The most critical pathogens. Pathogens 10, 1310 (2021).

Namivandi-Zangeneh, R., Wong, E. H. & Boyer, C. Synthetic antimicrobial polymers in combination therapy: Tackling antibiotic resistance. ACS Infectious Dis. 7, 215–253 (2021).

Türkyılmaz, O. & Darcan, C. The emergence and preventability of globally spreading antibiotic resistance: A literature review. Biol. Bullet. Rev. 13, 578–589 (2023).

Kwa, A. L. et al. Clinical utility of procalcitonin in implementation of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic stewardship in the south-east Asia and India: Evidence and consensus-based recommendations. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Ther. 22(1–3), 45–58 (2024).

Rios, A. C. et al. Alternatives to overcoming bacterial resistances: State-of-the-art. Microbiol. Res. 191, 51–80 (2016).

Wilson, D. N., Hauryliuk, V., Atkinson, G. C. & O’Neill, A. J. Target protection as a key antibiotic resistance mechanism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 637–648 (2020).

Karmakar, R. State of the art of bacterial chemotaxis. J. Basic Microbiol. 61, 366–379 (2021).

Ghai, I. & Ghai, S. Understanding antibiotic resistance via outer membrane permeability. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 523–530 (2018).

Collins, J. A., Oviatt, A. A., Chan, P. F. & Osheroff, N. Target-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance in neisseria gonorrhoeae: Actions of ciprofloxacin against gyrase and topoisomerase IV. ACS Infect. Dis. 10(4), 1351–1360 (2024).

Prasher, P. et al. Emerging trends in clinical implications of bio-conjugated silver nanoparticles in drug delivery. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 35, 100244 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. Albumin-coated green-synthesized zinc oxide nanoflowers inhibit skin melanoma cells growth via intra-cellular oxidative stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 263, 130694 (2024).

Mariadoss, A. V. A., Saravanakumar, K., Sathiyaseelan, A., Venkatachalam, K. & Wang, M.-H. Folic acid functionalized starch encapsulated green synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 2073–2084 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Leucine-coated cobalt ferrite nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and potential biomedical applications for drug delivery. Phys. Lett. A 384, 126600 (2020).

Kamal, R. et al. Evaluation of cephalexin-loaded PHBV nanofibers for MRSA-infected diabetic foot ulcers treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 1(71), 103349 (2022).

Hussan, S., Nisa, S. A. & Bano, M. Zia, Chemically synthesized ciprofloxacin-PEG-FeO nanotherapeutic exhibits strong antibacterial and controlled cytotoxic effects. Nanomedicine 19, 875–893 (2024).

Nzilu, D. M. et al. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its efficiency in degradation of rifampicin antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 13, 14030 (2023).

Abbas, S. et al. Dual-functional green facile CuO/MgO nanosheets composite as an efficient antimicrobial agent and photocatalyst. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 5895–5909 (2022).

Javed, R., Ahmed, M., UlHaq, I., Nisa, S. & Zia, M. PVP and PEG doped CuO nanoparticles are more biologically active: Antibacterial, antioxidant, antidiabetic and cytotoxic perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 1(79), 108–115 (2017).

Liu, Z., Wang, K., Wang, T., Wang, Y. & Ge, Y. Copper nanoparticles supported on polyethylene glycol-modified magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles: Its anti-human gastric cancer investigation. Arab. J. Chem. 15, 103523 (2022).

Knop, K., Hoogenboom, R., Fischer, D. & Schubert, U. S. Poly (ethylene glycol) in drug delivery: Pros and cons as well as potential alternatives. Angewandte Chem. Int. Ed. 49(36), 6288–6308 (2010).

Chen, S. et al. Targeting tumor microenvironment with PEG-based amphiphilic nanoparticles to overcome chemoresistance. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 12, 269–286 (2016).

Ibne Shoukani, H. et al. Ciprofloxacin loaded PEG coated ZnO nanoparticles with enhanced antibacterial and wound healing effects. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4689 (2024).

Milla, P. G., Peñalver, R. & Nieto, G. Health benefits of uses and applications of Moringa oleifera in bakery products. Plants. 10(2), 318 (2021).

Vongsak, B. et al. Maximizing total phenolics, total flavonoids contents and antioxidant activity of Moringa oleifera leaf extract by the appropriate extraction method. Indus. Crops Products 44, 566–571 (2013).

Berkovich, L. et al. Moringa Oleifera aqueous leaf extract down-regulates nuclear factor-kappaB and increases cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Complement. Alternat. Med. 13, 212 (2013).

Murugan, B. et al. Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles for biological applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 19, 111088 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. One-step fabrication of PEGylated fluorescent nanodiamonds through the thiol-ene click reaction and their potential for biological imaging. Appl. Surf. Sci. 439, 1143–1151 (2018).

Varela-Moreira, A. et al. Utilizing in vitro drug release assays to predict in vivo drug retention in micelles. Int. J. Pharmac. 618, 121638 (2022).

Hamdan, S. et al. Nanotechnology-driven therapeutic interventions in wound healing: Potential uses and applications. ACS Central Sci. 3, 163–175 (2017).

Matter, M. T., Probst, S., Läuchli, S. & Herrmann, I. K. Uniting drug and delivery: Metal oxide hybrid nanotherapeutics for skin wound care. Pharmaceutics. 12(8), 780 (2020).

Castro, A. L. et al. Colombian tigecycline susceptibility surveillance group. Comparing in vitro activity of tigecycline by using the disk diffusion test, the manual microdilution method, and the VITEK 2 automated system. Rev. Argentina de Microbiol. 42(3), 208–211 (2010).

Haney, E. F., Trimble, M. J. & Hancock, R. E. W. Microtiter plate assays to assess antibiofilm activity against bacteria. Nat. Protocols 16, 2615–2632 (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. Chitosan modified magnetic nanocomposite for biofilm destruction and precise photothermal/photodynamic therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 259, 129402 (2024).

Chen, Z., Bertin, R. & Froldi, G. EC50 estimation of antioxidant activity in DPPH· assay using several statistical programs. Food Chem. 138, 414–420 (2013).

Sato, A. et al. Extracellular leakage protein patterns in two types of cancer cell death: Necrosis and apoptosis. ACS Omega 8, 25059–25065 (2023).

Prasad, M. et al. Nanotherapeutics: An insight into healthcare and multi-dimensional applications in medical sector of the modern world. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1(97), 1521–1537 (2018).

S. Liu, H. Liu, Z. Yin, K. Guo, X. Gao, Cytotoxicity of pristine C 60 fullerene on baby hamster kidney cells in solution, (2012).

Nabila, M. I. & Kannabiran, K. Biosynthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) from actinomycetes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 15, 56–62 (2018).

Badawy, A. A., Abdelfattah, N. A., Salem, S. S., Awad, M. F. & Fouda, A. Efficacy assessment of biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) on stored grain insects and their impacts on morphological and physiological traits of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plant. Biology. 10(3), 233 (2021).

Mobarak, M. B., Hossain, M. S., Chowdhury, F. & Ahmed, S. Synthesis and characterization of CuO nanoparticles utilizing waste fish scale and exploitation of XRD peak profile analysis for approximating the structural parameters. Arab. J. Chem. 15(10), 104117 (2022).

Reddy, K. R. Green synthesis, morphological and optical studies of CuO nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 1150, 553–557 (2017).

Neckel, U. et al. Simultaneous determination of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in microdialysates and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 463, 199–206 (2002).

Do, B. L. et al. Green synthesis of nano-silver and its antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27(5), 101722 (2023).

Gong, X. et al. An overview of green synthesized silver nanoparticles towards bioactive antibacterial, antimicrobial and antifungal applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 323, 103053 (2024).

Rodríguez-Melcón, C., Alonso-Calleja, C., García-Fernández, C., Carballo, J. & Capita, R. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) for twelve antimicrobials (biocides and antibiotics) in eight strains of listeria monocytogenes. Biology. 11(1), 46 (2021).

Velsankar, K., Suganya, S., Muthumari, P., Mohandoss, S. & Sudhahar, S. Ecofriendly green synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications of CuO nanoparticles synthesized using leaf extract of Capsicum frutescens. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(5), 106299 (2021).

Shkodenko, L., Kassirov, I. & Koshel, E. Metal oxide nanoparticles against bacterial biofilms: Perspectives and limitations. Microorganisms. 8(10), 1545 (2020).

Suh, S., Traore, M. A. & Behkam, B. Bacterial chemotaxis-enabled autonomous sorting of nanoparticles of comparable sizes. Lab Chip 16, 1254–1260 (2016).

Kaningini, A. G., Motlhalamme, T., More, G. K., Mohale, K. C. & Maaza, M. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties of biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) using Athrixia phylicoides DC. Heliyon 9, e15265 (2023).

Sadeghi, S. et al. Copper-oxide nanoparticles effects on goldfish (Carassius auratus): Lethal toxicity, haematological, and biochemical effects. Vet. Res. Commun. 48, 1611–1620 (2024).

Masson-Meyers, D. S. et al. Experimental models and methods for cutaneous wound healing assessment. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 101, 21–37 (2020).

Stephens, P., Caley, M. & Peake, M. Alternatives for animal wound model systems 177–201 (Methods and Protocols, Wound Regeneration and Repair, 2013).

Song, J., Razzaq, A., Khan, N. U., Iqbal, H. & Ni, J. Chitosan/poly (3-hydroxy butyric acid-co-3-hydroxy valeric acid) electrospun nanofibers with cephradine for superficial incisional skin wound infection management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 250, 126229 (2023).

Gulin-Sarfraz, T., D’Alfonso, L., Smått, J.-H., Chirico, G. & Sarfraz, J. The antimicrobial and photothermal response of copper sulfide particles with distinct size and morphology. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 38, 101156 (2024).

Mitchell, M. J. et al. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 101–124 (2021).

Suri, S. S., Fenniri, H. & Singh, B. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2, 16 (2007).

Naz, S., Gul, A., Zia, M. & Javed, R. Synthesis, biomedical applications, and toxicity of CuO nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 1039–1061 (2023).

Verma, N. & Kumar, N. Synthesis and biomedical applications of copper oxide nanoparticles: An expanding horizon. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 1170–1188 (2019).

Hwang, C., Choi, M.-H., Kim, H.-E., Jeong, S.-H. & Park, J.-U. Reactive oxygen species-generating hydrogel platform for enhanced antibacterial therapy. NPG Asia Materials 14, 72 (2022).

Keegstra, J. M., Carrara, F. & Stocker, R. The ecological roles of bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 491–504 (2022).

Bi, S. & Lai, L. Bacterial chemoreceptors and chemoeffectors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 691–708 (2015).

Kamaly, N., Yameen, B., Wu, J. & Farokhzad, O. C. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: Mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem. Rev. 116, 2602–2663 (2016).

Xu, J., Chen, Y., Jiang, X., Gui, Z. & Zhang, L. Development of hydrophilic drug encapsulation and controlled release using a modified nanoprecipitation method. Processes 7, 331 (2019).

Makabenta, J. M. V. et al. Nanomaterial-based therapeutics for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 23–36 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-29).

Institutional review board statement

The present study was approved by the Departmental or Institutional Review, Graduate Research Committee of the University of Haripur, Pakistan

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024–29).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization by S. Nisa and Hussan.; Methodology by S. Nisa, Hussan, and Y. Bibi.; Software Hussan.; Validation S. Nisa formal analysis A.Ashfaq.; Investigation S. Nisa.; Resources S. Alharthi.; Data interpretation A.Ali and S. Alharthi.; Writing A.Ali.; Hussan.; Review and Editing A.Ali, S. Nisa and S. Alharthi. Khudija tul Kubra and Muhammad Zia .; Visualization by S. Alharthi and S. Nisa.; Supervision S. Nisa. A.Ali; Project administration, S. Nisa and A.Ali. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The experimental protocols involving the use of animals for research purpose were approved by the University of Haripur committee for animals study. All experimental protocols were approved by the committee of bioethics, University of Haripur, Pakistan. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of University of Haripur, Pakistan. An informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian (s).

Informed consent

Consent was obtained from all volunteers involved in the study, informed briefly that the provided blood samples will be exclusively processed for research purposes only.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibne Shoukani, H., Nisa, S., Bibi, Y. et al. Green synthesis of polyethylene glycol coated, ciprofloxacin loaded CuO nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep 14, 21246 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72322-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72322-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Bio-mediated synthesis of CuO, ZnO and CuO/ZnO particles using Combretum indicum flower extract for water treatment

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2026)

-

PEGylation of cupric oxide nanoparticles: modulation of in vitro cytotoxicity against cancer cells with unaltered antimicrobial properties

Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali (2025)

-

A Comprehensive Review of Toxicological Evaluations of NPs and Their Optimization for Biomedical Applications

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)

-

Development of Polyethylene Glycol–Coated CuO Nanocomposites for Enhanced Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Biocompatible and Anticancer Activities

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)