Abstract

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is a common neurological injury following very preterm birth. Resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is associated with injury severity; yet, fMRI is impractical for use in intensive care settings. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) measures RSFC through cerebral hemodynamics and has greater bedside accessibility than fMRI. We evaluated RSFC in preterm neonates with IVH using fNIRS and fMRI at term-equivalent age, and compared fNIRS connectivity between healthy newborns and those with IVH. Sixteen very preterm born neonates were scanned with fMRI and fNIRS. Additionally, fifteen healthy newborns were scanned with fNIRS. In preterms with IVH, fNIRS and fMRI connectivity maps were compared using Euclidean and Jaccard distances. The severity of IVH in relation to fNIRS-RSFC strength was examined using generalized linear models. fNIRS and fMRI RSFC maps showed good correspondence. Connectivity strength was significantly lower in healthy newborns (p-value = 0.023) and preterm infants with mild IVH (p-value = 0.026) compared to infants with moderate/severe IVH. fNIRS has potential to be a new bedside tool for assessing brain injury and monitoring cerebral hemodynamics, as well as a promising biomarker for IVH severity in very preterm born infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Germinal matrix-intraventricular hemorrhage (GMH-IVH) continues to be a major morbidity amongst neonates born premature prior to 32 weeks of gestation1,2,3. Based on the severity, GMH-IVH is classified into four grades: grade 1, hemorrhage confined to the germinal matrix; grade 2, occupying < 50% of the ventricle; grade 3, distending and occupying > 50% of the ventricle, and grade 4—IVH with intraparenchymal hemorrhage4. GMH-IVH directly or its consequence such as post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) may lead to injury to the developing periventricular white matter that can be seen on conventional imaging at term equivalent age (TEA)5. Furthermore, some of these effects persist later in life, impacting language, cognitive, behavioural, and motor domains6.

More recently, the use of resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been employed to gain a better understanding of brain injury and the impact on brain function, indicating this can be a promising biomarker7,8,9,10. The blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal, measured by fMRI, captures the relative change of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HHb) induced by neuronal activation through the mechanism of neurovascular coupling11. Yet it is also evident that during resting state, the brain remains active, and regions with similar functions tend to have more synchronized BOLD signals, which forms the basis for analyzing RSFC12. RSFC has provided new perspectives for studying brain injury in preterm infants8,10,13. fMRI-based RSFC in neonates with perinatal brain injury was predictive of motor skills at 8 months of age14. Yet, the clinical utility of functional MRI is limited due to its accessibility. MRI may be impractical for use with some neonates with IVH who cannot be transported away from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Functional connectivity determined from fMRI shows BOLD signal alterations and is more reflective of HHb15. Functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive and light-based brain imaging technique that can be used to map functional connectivity at the bedside. fNIRS also exploits the process of neurovascular coupling and measures the absorption of near-infrared light by hemoglobin9. Hence, oxygenation of the cerebral cortex is derived as an indirect measurement of neural activity. Indices reflective of cerebral oxygenation, including, HHb, HbO and total hemoglobin, can be estimated using fNIRS. This technique is an extremely convenient neuromonitoring tool, that can be used at the bedside, with minimal handling of fragile neonates.

GMH-IVH, regardless of grade, has been associated with disrupted functional connectivity in neonates16,17,18. RSFC has been associated with ventricular volumes in very preterm born neonates with PHVD18, indicating that this method can reliably be used at the bedside in the NICU. Given the strong need for bedside tools to monitor injury patterns in very preterm born neonates and evidence suggesting that fNIRS-based RSFC is comparable to fMRI in adults19, we sought to compare RSFC maps acquired using fNIRS and fMRI in very preterm neonates with IVH who were assessed at TEA. We also aimed to investigate whether fNIRS-based RSFC in preterm infants would be associated with the severity of IVH, compared to healthy term-born neonates. Our overall hypothesis was that fNIRS-based measures of RSFC would be comparable to that obtained with fMRI and that severity of injury would be associated with changes in RSFC patterns.

Methods

Participants

This was a prospective observational cohort study. Study participants were recruited from the NICU at the London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC), London, Canada between January 2020, and December 2022. Preterm neonates were eligible for inclusion based on the following criteria: ≤ 32 weeks’ gestational age (GA), born at, or referred to the NICU, and admitted with a diagnosis of GMH-IVH, made by the most responsible physician based on the infant’s first routine cranial ultrasound. Exclusion criteria were the following: major anomalies of the brain or other organs, congenital infections, intrauterine growth restriction, metabolic disorders, and ultrasound evidence of a large parenchymal haemorrhagic infarction. Term-born infants with no reported brain injury were recruited as healthy controls. Participants were recruited from the LHSC Mother baby Care Unit (MBCU). Inclusion criteria were birth > 36 weeks’ GA, born at LHSC, and were admitted to the MBCU. Exclusion criteria were the following: congenital malformations or syndromes, antenatal infections, antenatal exposure to illicit drugs, small for gestational age and intrauterine growth restriction.

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at Western University (116142). Informed consent was provided by the parents/caregivers of the infants enrolled in the study. Informed consent was obtained to publish the information/image(s) of participants in an online open access publication. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical variables

The neonatal charts were reviewed by Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Fellows (LMNK, TA, SR, MM), Paediatric Resident (AK), Research Associate (HV) or an NICU Nurse (PM) for demographic and clinical characteristics. The following postnatal events were included: days of mechanical ventilation, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment, days of parenteral nutrition, culture positive sepsis, and necrotizing enterocolitis.

MRI acquisition & image analysis

Anatomical and functional MRI images were acquired on a 1.5 T GE scanner at LHSC. Each infant underwent a clinical MRI scan consisting of a whole-brain T1-weighted structural image (TR = 8.4–11.5 ms [depending on clinical requirements], TE = 4.2 ms, flip angle = 12/25°, matrix size 512 × 512, 99–268 slices, voxel size typically 0.39 × 0.39 × 0.5 mm (0.31 × 31 × 5 to 0.43 × 0.43 × 0.6 for some infants), and a T2-weighted structural image (TR = 3517–9832 ms, TE = 7.3–8.4 ms, flip angle = 90/160°, matrix size 256 × 256, 19–60 slices, 0.7 × 0.7 × 2–5 mm voxel resolution). BOLD fMRI data were acquired using an echo planar imaging sequence to examine resting-state functional connectivity (TR = 3000 ms, TE = 50 ms, flip angle = 70°, matrix size 64 × 64, 39 slices, voxel size 3 × 3 × 3 mm, total volumes 35).

Preprocessing of fMRI images was conducted with FMRIB Software Library (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSL). The pipeline included brain extraction, motion correction, spatial smoothing (full width at half maximum = 5 mm), band-pass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz) and registration to a neonatal atlas20. Average BOLD sequences were extracted from frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes of both hemispheres, and then correlated to build an 8-by-8 lobe-wise RSFC map for each neonate.

Brain injury characterization

A Neuroradiology Fellow (LTARdM) scored the T1-weighted anatomical images for brain injury severity. These scores were verified by a Paediatric Neuroradiologist. IVH was graded (mild = 1–2, and moderate-severe = 3–4) using Papile’s method4.

fNIRS acquisition & analysis

All participants (preterm infants with IVH and healthy newborns) were scanned with a NIRSport2 (NIRx, Berlin, Germany) system with two emission wavelengths (760 and 850 nm). We used an 8-by-8 set up with 20 channels covering the whole brain, and a sampling rate of 10.17 Hz. For each hemisphere, there were 4 channels on the temporal, 2 on the parietal, frontal and occipital lobes. On average, scans lasted 487.46 s (with a standard deviation of 116.17 s) across all participants. For each infant, a 6-min segment of high-quality data, determined through visual inspection, was selected for further analysis.

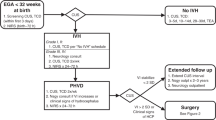

After data acquisition, for the fNIRS recordings in each infant, the data were visually inspected to select a 6-min segment with the least motion artifacts and background noise. A preprocessing pipeline, built within Homer 3 software, included spline interpolation for motion correction21, Savitzky–Golay filtering22 with frame size of 10, band-pass filtering of 0.01–0.1 Hz and modified Beer-Lamber law to convert optical density to concentration changes in HbO and HHb, respectively23. Pearson correlations were used to calculate connectivity. To compare RSFC maps between fNIRS and fMRI, channels corresponding to one lobe were averaged then correlated with the other lobes to create 8-by-8 lobe-wise connectivity maps for HbO and HHb, respectively (Fig. 1b,c,d). For lobe-wise maps of both fNIRS and fMRI, nodes were lobes and edges were weighted by Pearson correlation coefficients between sequences of the two lobes. 20-by-20 channel-wise RSFC maps were also calculated for fNIRS (Fig. 1a), yet in this map, nodes were fNIRS channels.

Examples of (a) a 20-by-20 connectivity map and (b) an 8-by-8 map for the signals extracted from the fNIRS channels in the left and right hemispheres from the temporal, parietal, frontal and occipital lobes. The 8-by-8 map was obtained by averaging fNIRS signals from one lobe then correlating with each other. (c) Lobe-based analysis of the fMRI data. A hemisphere was sectioned into temporal, parietal, frontal and occipital lobes. (d) Based on the section, a connectivity map was built from the fMRI image using averaged BOLD series from each region. All figures were developed from the data from the same participant in the IVH group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using a combination of Matlab (R2020b, Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc) and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v.29, Chicago, IL).

To address our first aim, to determine whether the RSFC maps developed from the fNIRS and fMRI data were comparable, we calculated the Euclidean and Jaccard distances between the two lobe-wise maps at various levels of sparsity for each participant and for both weighted and binarized maps24. The sparsity was the percentage of non-zero connections that remained in a RSFC map after several other connections were removed (set to zero). A common practice is to start by removing the lowest weighted ones, including negative ones, then continuing to remove the lowest weighted ones until the sparsity reaches the desired percentage. Weighted maps were obtained using this method. Binarized maps were then calculated with non-zero connections set to 1. In general, there is no standard for choosing the sparsity25, therefore, the range 0.2–0.4 was tested in this study. With sparsity of 0.4, negative connections, of which the interpretations have been mixed in the literature, were removed26. And with 0.2, the maps became sparser but could still stay connected while a representational number of connections remained, as the maps were only 8-by-8. Given maps \({G}_{fMRI}\left(V,{E}_{fMRI}\right)\) and \({G}_{fNIRS}\left(V,{E}_{fNIRS}\right)\) obtained from the two modalities, where \(V\) and \(E\) denote node and connection set, respectively, and their adjacency matrices \({A}_{fMRI}=\left[{a}_{ij}^{fMRI}\right]\) and \({A}_{fNIRS}=\left[{a}_{ij}^{fNIRS}\right]\), respectively, where \(i\) and \(j\) are nodes, the Euclidean distance between two maps was defined as.

The Jaccard distance for weighted maps was defined as.

where \({J}_{w}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\frac{{\sum }_{i,j}\text{min}\left({a}_{ij}^{fNIRS},{a}_{ij}^{fMRI}\right)}{{\sum }_{i,j}\text{max}\left({a}_{ij}^{fNIRS},{a}_{ij}^{fMRI}\right)}, if {\sum }_{i,j}\text{max}\left({a}_{ij}^{fNIRS},{a}_{ij}^{fMRI}\right)>0\\ 1, otherwise\end{array}\right.\)

While for binarized maps, the Jaccard distance was defined as.

One level of sparsity yielding the most similarity between two modalities was selected for the subsequent analyses. Based on this specific sparsity, we also calculated similarity maps for weighted and binarized RSFC maps. The similarity map was defined as.

where \({s}_{ij}=1-\frac{1}{N}{\sum }_{n=1}^{N}\left|{a}_{ij}^{fNIRS,n}-{a}_{ij}^{fMRI,n}\right|\),

where \({a}_{ij}^{fNIRS,n}\) and \({a}_{ij}^{fMRI,n}\) are entries of individual adjacency matrices of \({n}^{th}\) subject from a total of \(N\). Note that for weighted RSFC maps, \({s}_{ij}\) was an index based on Euclidean distance, while for binarized maps, \({s}_{ij}\) equals to the percentage of subjects sharing the connection.

We addressed our second aim, concerning whether fNIRS-based RSFC would predict IVH severity in very preterm born neonates compared to healthy newborns, in generalized linear models (GLM), which offer more clincally interpretable results through \(\beta\) values. In the first model, the summation of weighted connectivity values of the whole brain for HHb were entered as the dependent variable, with IVH grade (none [healthy newborns], mild, moderate-severe) as a factor, adjusting for biological sex, GA, and postmenstrual age (PMA) at scan. In the second model, HbO connectivity values were entered as the dependent variable, using the identical independent variables as in the first model. It was assumed the connectivity values followed a Gaussian distribution, and the tests among groups were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction method.

Results

Participants

Sixteen very preterm born neonates with GMH-IVH were enrolled (mean GA at birth = 26.28 weeks, standard deviation [SD] = 2.82 weeks). All preterm infants underwent MRI scanning at TEA (mean GA at scan = 37.04 weeks, SD = 0.96 weeks). In eleven participants, fNIRS was also acquired. A total of 15 term-born infants were recruited from the LHSC MBCU with mean birth GA of 38.92 (SD = 1.30) weeks and fNIRS scans performed within 48 h of life. None of the healthy newborns underwent MRI. Detailed demographics of participants can be found in Table 1. Clinical variables of the IVH group can be found in Table 2. Most of the infants were scanned during natural sleep for the fNIRS and fMRI scans. The preterm born infants were receiving care in incubators during the fNIRS scans and healthy newborns were scanned either in their caregivers arms or in their cots.

Comparing fNIRS and fMRI

Lobe-wise connectivity maps were obtained from fNIRS for both HbO and HHb. The fNIRS maps were then compared against fMRI RSFC maps at various levels of sparsity using metrices of Euclidean and Jaccard distances. Only large- and positive-weighted connections were kept when achieving for a certain level of sparsity. Sparsity ranged from 0.2 to 0.4. At 38% of sparsity, for both weighted and binarized maps, for both HbO and HHb maps, least Euclidean and Jaccard distances were achieved (i.e., the fNIRS and fMRI yielded most similar RSFC maps, Fig. 2). Therefore, in the subsequent analyses, this level of sparsity was applied.

Based on the sparsity of 38%, the similarity maps were calculated comparing every connection between fNIRS and fMRI. Similarity maps of HbO compared against fMRI and HHb evaluated relative to fMRI showed good correspondence for both weighted and binarized cases (Fig. 3). This is largely a reflection of the anti-correlation between the two chromophores, yielding similar RSFC maps. Additionally, the majority of connections that demonstrated high correspondence were interhemispheric.

Lobe-wise similarity maps at sparsity of 38%. Higher values reflect greater similarity between the two modalities. Average values among channels were 0.55 (upper left, standard deviation [SD] 0.16, CI 0.48–0.61), 0.66 (lower left, SD 0.18, CI 0.59–0.73), 0.49 (upper right, SD 0.16, CI 0.43–0.55) and 0.63 (lower right, SD 0.19, CI 0.56–0.71).

Connectivity and severity of IVH

In a GLM, the functional connectivity within the cortical network was examined in relation to IVH severity (none [healthy newborns], mild IVH, moderate/severe IVH). The weighted connectivity values for HHb were significantly lower in healthy newborns (B = − 53.5, 95%, CI − 94.61—− 12.39, p = 0.011, Table 3, Fig. 4), and preterm neonates with mild IVH (B = − 24.7, 95%, CI − 42.7- − 6.7, p = 0.007) compared to preterms with moderate/severe IVH adjusting for birth GA, sex, and PMA at scan. No significant differences in HHb connectivity values were evident between the healthy newborns and very preterm born neonates with mild IVH (p = 0.5, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). The weighted connectivity values were also significantly lower when examining HbO in a separate GLM, whereby healthy newborns (B = − 42.6, 95%, CI − 79.1- − 6.0, p = 0.023, Table 3, Fig. 4) and very preterm neonates with mild IVH (B = − 18.2, 95%, CI − 34.3- − 2.2, p = 0.026) had lower values when compared to very preterm born neonates with moderate/severe IVH. No differences were evident between the HbO sparsity values for healthy newborns and neonates with mild IVH (p = 0.6, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). Similar analyses were performed for the fMRI data; yet, we found no significant differences (p > 0.05) in connectivity strength between mild and moderate/severe injury patterns.

Discussion

In a prospective cohort of very preterm born infants with IVH, we examined the predictive utility of fNIRS connectivity in assessing brain health. As expected, RSFC maps were comparable between fMRI and fNIRS in very preterm born infants with IVH. Findings indicate that fNIRS can be used to study cortical RSFC at the bedside. We further examined whether the severity of injury could be predicted by functional connectivity metrics. We found that for both HHb and HbO, the connectivity values at TEA were increased in infants with moderate/severe IVH relative to healthy newborns and very preterm born infants with mild IVH. Overall, our results highlight the use of fNIRS as a bedside monitoring tool to examine brain-health metrics in very preterm born neonates with IVH.

We saw good correspondence of the RSFC maps (HbO vs fMRI and HHb vs fMRI) between the two imaging modalities. Our findings are consistent with other studies. For example, Duan et al., using fNIRS and fMRI data acquired from 21 adult participants during resting state, and demonstrated good correspondence between the two imaging modalities19. In another adult study, Sasai et al. also reported that fNIRS HbO and fMRI BOLD maps demonstrated significant positive correlations for all brain regions investigated27. We were able to demonstrate similar results in our neonatal population. Second, except for the occipital region, the other regions (frontal, parietal and temporal) showed high levels of similarity between the RSFC maps for the two imaging modalities. The discrepancy in the occipital region could be because of measurement errors, including thick hair, poor contact between optodes and scalp, cap fit, which are common in fNIRS studies in infants9,15,28. In addition, all our bedside fNIRS measurements were carried out with the neonates laying supine in their incubator, cot or caregivers' arms which could explain the poor optode contact in the occipital region. Overall, our study adds to the body of literature showing that fNIRS indeed provides comparable RSFC measures to fMRI. This is especially important given the bedside availability of fNIRS for this vulnerable NICU population.

RSFC of fMRI BOLD was compared to HbO and HHb maps, respectively. It is commonly considered that HHb is more similar to BOLD since the biophysical basis of fMRI relies on the magnetic properties of deoxygenated hemoglobin29, yet in our comparisons, we showed that HbO RSFC was more similar to fMRI with lower between-modality distances at various sparsity levels (Fig. 2) and higher averaged similarity (Fig. 3). Previous studies also gave inconsistent findings on this issue. Toronov et al. showed that the BOLD response in the motor cortex was more strongly associated with HHb than HbO30, yet the same group later found that spatial localization of visual networks was more consistent between HbO and BOLD31. In terms of RSFC, Duan et al. reported greater correlation coefficients between BOLD and HbO compared to HHb19, and the authors indicated that their findings may reflect HbO having higher signal-to-noise ratio compared to HHb32, and higher reliability of detecting RSFC33. Yet it was also pointed out by Abdalmalak et al. that HbO is more sensitive to systemic physiology than HHb34. To avoid statistical multiplicity, future analyses to determine whether HbO or HHb better represents true RSFC is needed.

Filtering connections that are either negative- or low-weighted is a common practice for fNIRS RSFC research35. RSFC yielded from various sparsity levels were tested in previous studies, and demonstrated inconsistent results36,37,38,39. Recent studies have highlighted the necessity of selecting proper sparsity values and have introduced various strategies40,41. In the current work, we have addressed this issue by identifying a maximal similarity value for the two imaging modalities (i.e., fNIRS and fMRI). For future research in fNIRS RSFC with neonates, this method may be impractical without access to another imaging modality such as fMRI. Yet, potentially this challenge can be overcome through scanning larger numbers of neonates, as this will aid in identifying a sparsity level that could be more universally applicable for neonatal RSFC studies.

Compared with their healthy counterparts, we found increased RSFC at TEA among infants with IVH, regardless of the severity. This was an unexpected finding, as most studies of very preterm infants with IVH have demonstrated reduced RSFC at TEA13,16,17,42. Reduced RSFC, especially in higher grades of IVH injury is attributed to disruptions to the periventricular white matter. However, some studies have also shown intact RSFC in infants with IVH43. The results from our study, while different from what is previously known in literature, could be explained by several possible mechanisms. First, our study population was very preterm (<32 weeks' gestation), with IVH within the first week of life and our findings represent the RSFC 10–12 weeks post IVH. Thereafter, during their NICU stay and with ongoing surveillance, depending on the IVH severity, some of the study participants underwent neurosurgical interventions to divert cerebrospinal fluid. In tandem with the above-mentioned, over time the neonatal brain undergoes exponential growth and reorganization, demonstrating a mature architecture by TEA44,45. Moreover, some case studies have shown neural plasticity in infants with high grades of IVH46. Immaturity of neurovascular coupling mechanisms also could have influenced the increased connectivity seen in the IVH group. It was previously reported in animal models that newborns showed globally correlated hemodynamic fluctuations during resting state47, likely due to the absence of hyperemia, which is typically present in adults in response to neuronal activity. Also, preterm neonates with IVH, compared to those without, lack vascular responses needed for the compensation of increased metabolism after neuronal activation48. Therefore, the IVH group could also be expected to have even lower hemodynamic responses than healthy term newborns, which may have led to less distinction among brain regions rather than reflect increased connectivity. Hence, all these factors could explain our findings. These questions could be best addressed in future longitudinal studies, correlating RSFC with neurodevelopmental outcomes. Disruptions in neonatal functional connectivity in children with perinatal brain injuries have been associated with developmental outcomes, and in turn better characterization of these patterns is needed to improve early care practices14. In addition, we found no significant differences of connectivity strength on our fMRI dataset between mild and moderate/severe groups. One possible explanation of this is that fNIRS recordings were from more localized positions instead of whole lobules as in fMRI (i.e., some within-lobule alterations could be overlooked by averaging the lobules). Also, the level of localization (e.g., from voxel to anatomical regions) has been shown to have significant impact on network properties of RSFC49,50.

Our study has several strengths, namely, both groups (neonates with IVH and healthy controls) were recruited from and assessed at the same centre, using the same high-density fNIRS system and at similar postmenstrual ages. The above-mentioned measures ensure uniformity and eliminate potential biases. Second, compared to clinical NIRS systems that are now commonly used in most level III NICUs, high density fNIRS systems provide whole brain coverage and measures of connectivity. Our study population (preterm neonates with IVH and healthy controls) was also well characterized. However, some challenges and limitations with our study can be noted. Primarily, the sample size for our study population was small. This was due to difficulty acquiring excellent quality data, which is a challenge for fNIRS studies28. These challenges could potentially be addressed through the development of hardware specifically designed for neonates. Appropriate and effective hardware may also promote greater ease of use of fNIRS in NICU-settings. Also, our eventual goal is to use fNIRS for clinical decision making in individual neonates at the bedside. Despite some signals of poor quality, we were still able to show comparable fNIRS and fMRI connectivity maps and discriminative fNIRS features for separating the groups. Second, more males than females were recruited, due to lack of competitive enrolment. However, sex differences were not evident in any analyses. Thirdly, including a group of preterm infants without brain injury would strengthen the study and would allow for a clearer comparison of functional connectivity and brain injury. This is in consideration of evidence suggesting that preterm newborns without known brain injuries can also exhibit altered functional connectivity51,52. Another limitation is that the positions of the fNIRS optodes could not be precisely registered into MRI space, therefore, we could not perform more localized analysis to assess the similarity between the two modalities and how the severity of IVH affects RSFC. As a compromise, we could only implement a lobe-wise analysis for the fMRI data that corresponded to coverage of the fNIRS channels. In addition, some potential covariates were not analyzed (e.g., clinical variables, whether the neonates were scanned in incubators or caregivers’ arms). However, the sample size of this study was not large enough to include the full range covariates in the GLM models. Finally, though the classic Papile’s method4 for grading IVH severity was used for our population, it is acknowledged that there is a new and more detailed descriptive method for GMH-IVH classification53. Despite these limitations, we believe that fNIRS offers promising avenues that could inform the clinical care of preterm neonates with IVH. Larger prospective studies are needed to address the above mentioned challenges.

Conclusions

In a heterogenous cohort of very preterm born neonates with IVH who underwent fNIRS and fMRI we report comparable RSFC maps between the two modalities. Findings indicate, that in a small sample of neonates that bedside fNIRS can produce comparable results to that of fMRI. Secondly, fNIRS revealed distinct RSFC patterns between preterm infants with IVH at TEA and healthy infants. Larger prospective studies are needed to better characterize fNIRS-based functional connectivity changes over time and whether they are predictive of functional outcomes.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ballabh, P. Pathogenesis and prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage. Clin. Perinatol. 41, 47–67 (2014).

Siffel, C., Kistler, K. D. & Sarda, S. P. Global incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage among extremely preterm infants: A systematic literature review. J. Perinat. Med. 49, 1017–1026 (2021).

McAllister, J. P. et al. Ventricular zone disruption in human neonates with intraventricular hemorrhage. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 76, 358–375 (2017).

Papile, L. A., Burstein, J., Burstein, R. & Koffler, H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: A study of infants with birth weights less than 1500 gm. J. Pediatr. 92, 529–534 (1978).

Inder, T. E. et al. Neuroimaging of the Preterm Brain: Review and Recommendations. J. Pediatr. 237, 276-287.e4 (2021).

Vohr, B. R. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants with intraventricular hemorrhage across a lifespan. Semin. Perinatol. 46, 151594 (2022).

Doria, V. et al. Emergence of resting state networks in the preterm human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 20015–20020 (2010).

Smyser, C. D. et al. Effects of white matter injury on resting state fMRI measures in prematurely born infants. PLoS One 8, e68098 (2013).

Wang, Q. et al. A review of functional near-infrared spectroscopy studies of motor and cognitive function in preterm infants. Neurosci. Bull. 36, 321–329 (2020).

Triplett, R. L. & Smyser, C. D. Neuroimaging of structural and functional connectivity in preterm infants with intraventricular hemorrhage. Semin. Perinatol. 46, 151593 (2022).

Phillips, A. A., Chan, F. H., Zheng, M. M. Z., Krassioukov, A. V. & Ainslie, P. N. Neurovascular coupling in humans: Physiology, methodological advances and clinical implications. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 36, 647–664 (2015).

Biswal, B., Zerrin Yetkin, F., Haughton, V. M. & Hyde, J. S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar mri. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541 (1995).

Duerden, E. G. et al. White matter injury predicts disrupted functional connectivity and microstructure in very preterm born neonates. NeuroImage Clin. 21, 101596 (2019).

Linke, A. C. et al. Disruption to functional networks in neonates with perinatal brain injury predicts motor skills at 8 months. Neuroimage (Amst) 18, 399 (2018).

Scarapicchia, V., Brown, C., Mayo, C. & Gawryluk, J. R. Functional magnetic resonance imaging and functional near-infrared spectroscopy: Insights from combined recording studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 1–12 (2017).

Argyropoulou, M. I. et al. Structural and functional brain connectivity in moderate–late preterm infants with low-grade intraventricular hemorrhage. Neuroradiology 64, 197–204 (2022).

Cha, J. H. et al. Altered structural brain networks at term-equivalent age in preterm infants with grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhage. Ital. J. Pediatr. 46, 43 (2020).

Kebaya, L. M. N. et al. Three-dimensional cranial ultrasound and functional near-infrared spectroscopy for bedside monitoring of intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm neonates. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–13 (2023).

Duan, L., Zhang, Y. J. & Zhu, C. Z. Quantitative comparison of resting-state functional connectivity derived from fNIRS and fMRI: A simultaneous recording study. Neuroimage 60, 2008–2018 (2012).

Makropoulos, A. et al. The developing human connectome project: A minimal processing pipeline for neonatal cortical surface reconstruction Europe PMC funders group. Neuroimage 173, 88–112 (2018).

Scholkmann, F., Spichtig, S., Muehlemann, T. & Wolf, M. How to detect and reduce movement artifacts in near-infrared imaging using moving standard deviation and spline interpolation. Physiol. Meas. 31, 649–662 (2010).

Jahani, S., Setarehdan, S. K., Boas, D. A. & Yücel, M. A. Motion artifact detection and correction in functional near-infrared spectroscopy: A new hybrid method based on spline interpolation method and Savitzky-Golay filtering. Neurophotonics 5, 1 (2018).

Kocsis, L., Herman, P. & Eke, A. The modified Beer-Lambert law revisited. Phys. Med. Biol. 51, N91–N98 (2006).

Tantardini, M., Ieva, F., Tajoli, L. & Piccardi, C. Comparing methods for comparing networks. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–19 (2019).

Garrison, K. A., Scheinost, D., Finn, E. S., Shen, X. & Constable, R. T. The (in)stability of functional brain network measures across thresholds. Neuroimage 118, 651–661 (2015).

Chen, G., Chen, G., Xie, C. & Li, S. J. Negative functional connectivity and its dependence on the shortest path length of positive network in the resting-state human brain. Brain Connect. 1, 195–206 (2011).

Sasai, S. et al. A NIRS-fMRI study of resting state network. Neuroimage 63, 179–193 (2012).

Gallagher, A., Wallois, F. & Obrig, H. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy in pediatric clinical research: Different pathophysiologies and promising clinical applications. Neurophotonics 10, 023517 (2023).

Buxton, R. B. The physics of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 096601 (2013).

Toronov, V. et al. The roles of changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration and regional cerebral blood volume in the fMRI BOLD signal. Neuroimage 19, 1521–1531 (2003).

Toronov, V. Y., Zhang, X. & Webb, A. G. A spatial and temporal comparison of hemodynamic signals measured using optical and functional magnetic resonance imaging during activation in the human primary visual cortex. Neuroimage 34, 1136 (2007).

Tong, Y., de Frederick, B. & B.,. Concurrent fNIRS and fMRI processing allows independent visualization of the propagation of pressure waves and bulk blood flow in the cerebral vasculature. Neuroimage 61, 1419–1427 (2012).

Xu, G. et al. Test-retest reliability of fNIRS in resting-state cortical activity and brain network assessment in stroke patients. Biomed. Opt. Exp. 14, 4217 (2023).

Abdalmalak, A. et al. Effects of systemic physiology on mapping resting-state networks using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Front. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.803297 (2022).

Sasai, S., Homae, F., Watanabe, H. & Taga, G. Frequency-specific functional connectivity in the brain during resting state revealed by NIRS. Neuroimage 56, 252–257 (2011).

Nguyen, T. et al. Exploring brain functional connectivity in rest and sleep states: A fNIRS study. Sci. Rep. 81(8), 1–10 (2018).

Einalou, Z., Maghooli, K., Setarehdan, S. K. & Akin, A. Graph theoretical approach to functional connectivity in prefrontal cortex via fNIRS. Neurophotonics 4, 041407 (2017).

Wang, M. Y., Lu, F. M., Hu, Z., Zhang, J. & Yuan, Z. Optical mapping of prefrontal brain connectivity and activation during emotion anticipation. Behav. Brain Res. 350, 122–128 (2018).

Tang, L. et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity in newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy assessed using high-density functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53256-0 (2024).

Chan, Y. L. et al. Automated thresholding method for fNIRS-based functional connectivity analysis: Validation with a case study on Alzheimer’s Disease. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28, 1691–1701 (2020).

Dimitriadis, S. I., Salis, C., Tarnanas, I. & Linden, D. E. Topological filtering of dynamic functional brain networks unfolds informative chronnectomics: A novel data-driven thresholding scheme based on orthogonal minimal spanning trees (OMSTs). Front. Neuroinform. 11, 238952 (2017).

Arichi, T. et al. The effects of hemorrhagic parenchymal infarction on the establishment of sensori-motor structural and functional connectivity in early infancy. Neuroradiology 56, 985–994 (2014).

Herzmann, C. et al. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to detect preserved function in a preterm infant with brain injury. J. Pediatr. 189, 213-217.e1 (2017).

Fransson, P. et al. Spontaneous brain activity in the newborn brain during natural sleep-an fMRI study in infants born at full term. Pediatr. Res. 66, 301–305 (2009).

Eyre, M. et al. The developing human connectome project: typical and disrupted perinatal functional connectivity. Brain 144, 2199–2213 (2021).

Guzzetta, A., Fiori, S., Scelfo, D., Conti, E. & Bancale, A. Reorganization of visual fields after periventricular haemorrhagic infarction: Potentials and limitations. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 55, 23–26 (2013).

Kozberg, M. G., Ma, Y., Shaik, M. A., Kim, S. H. & Hillman, E. M. C. Rapid postnatal expansion of neural networks occurs in an environment of altered neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling. J. Neurosci. 36, 6704–6717 (2016).

Mahmoudzadeh, M. et al. Consequence of intraventricular hemorrhage on neurovascular coupling evoked by speech syllables in preterm neonates. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 30, 60–69 (2018).

Hayasaka, S. & Laurienti, P. J. Comparison of characteristics between region-and voxel-based network analyses in resting-state fMRI data. Neuroimage 50, 499–508 (2010).

Korhonen, O., Saarimäki, H., Glerean, E., Sams, M. & Saramäki, J. Consistency of regions of interest as nodes of fMRI functional brain networks. Netw. Neurosci. 1, 254–274 (2017).

Barnes-Davis, M. E., Merhar, S. L., Holland, S. K., Parikh, N. A. & Kadis, D. S. Extremely preterm children demonstrate hyperconnectivity during verb generation: A multimodal approach. NeuroImage Clin. 30, 102589 (2021).

Barnes-Davis, M. E. et al. Structural connectivity at term equivalent age and language in preterm children at 2 years corrected. Brain Commun. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcae126 (2024).

Parodi, A. et al. Cranial ultrasound findings in preterm germinal matrix haemorrhage, sequelae and outcome. Pediatr. Res. 87, 13–24 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the families who participated in this study. We thank the staff from the NICU and MBCU at LHSC for their immense help during this study. We sincerely thank our colleague, the late Dr. Michael T. Jurkiewicz, for characterizing brain injuries identified on MRI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M.N.K, L.T, T.A, A.K, M.M, S.R, H.V, P.M, S.d.R, S.B, L.T.A.R.d.M, K.S.L and E.G.D were involved in the study design, data acquisition design and execution of data analytic strategy, revision of the final version of this manuscript. L.M.N.K, L.T and E.G.D wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and contributed to the execution of the data analytic strategy. L.T and E.G.D analyzed the data. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at Western University (116142). Informed consent was provided by the parents/caregivers of the infants enrolled in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kebaya, L.M.N., Tang, L., Altamimi, T. et al. Altered functional connectivity in preterm neonates with intraventricular hemorrhage assessed using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Sci Rep 14, 22300 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72515-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72515-8