Abstract

Serum uric acid (SUA) has been linked to mortality in heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. However, data are lacking on how it affects the mortality risk of patients with cardiovascluar disease (CVD). This study evaluated the data of 4 308 individuals from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2008 using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression, trend, restricted cubic splines (RCS), subgroup and inflection point analyses. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality accounted for 42.8% and 17.6% of cases, respectively, over a median 80- month follow-up. Upon control for confounding variables, no linear trend was seen in the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis between SUA and all-cause (P = 0.001) or cardiovascular death (P = 0.007) mortality. On the RCS analysis, SUA showed an L-shaped connection with all-cause (non-linear P < 0.001) and cardiovascular mortality (non-linear P = 0.003) mortality. On the inflection point analysis, patients with CVD and an SUA ≥ 6.127 mg/dL had an all-cause mortality hazard ratio of 1.146 (95% confidence interval, 1.078–1.217; P < 0.001), while those with CVD and an SUA ≥ 5.938 mg/dL had a cardiovascular mortality hazard ratio of 1.123 (95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.225; P = 0.007). In patients with CVD, higher SUA was non-linearly correlated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), which accounts for more than one in four fatalities, is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke accounted for an estimated 558 000 and 109 000 fatalities in 2019, respectively1. The entire healthcare system is heavily burdened financially by CVD, which is predicted to reach $368 billion annually by 20352. Patients with CVD are more likely to experience repeated unfavorable cardiovascular events despite the advancement of improved procedures and the widespread adoption of primary and secondary preventive strategies3. Consequently, identifying individuals at risk of CVD early in the disease process is clinically significant in terms of enhancing risk assessments and treatment planning. New risk factors for CVD are emerging from the international literature, despite the fact that multiple risk factors for CVD have already been documented, including age, male sex, obesity, hypertension, hypercholestrolemia, and diabetes. Uric acid (UA) stands out among them all4.

In higher animals like humans and the great apes, purine metabolism produces UA, which is primarily controlled by xanthine oxi-doreductase. The liver, intestines, muscles, and vascular endothelium all naturally produce UA5. Compared to inherited genetic variants, the total diet explains significantly less variance in serum UA (SUA) levels. However, the consumption of alcohol, red meat, shellfish, potatoes, and other foods can elevate exogenous UA levels6,7. However, as people lead increasingly unhealthy lives, the prevalence of hyperuricemia (high SUA levels) has risen to the fourth most common conditions, following only hypertension, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. Hyperuricemia affects an estimated 170 million people in China8 and 32.5 million in the US9. The significance that UA plays in the development of kidney stones and gout is well understood. On the other hand, its role in CVD is drawing increasing attention.

Studies in the mid-1950s and 1960s revealed a link between high SUA levels and CVD. These investigations identified a cardiovascular risk associated with a wide range of diseases, including hypertension, metabolic syndrome, coronary artery disease (CAD), vascular dementia, pre-eclampsia, and renal illnesses10. However, according to The Framingham Heart Study's mid-1990s findings, increased SUA levels, regardless of degree, carried no risk factor burden and had no association with cardiovascular or all-cause mortality11. Over time, evidence was gathered to substantiate the link between SUA levels and CVD. Increased UA levels may be an indicator or play an etiologic role in the development of cardiovascular risk factors and mortality related to disorders such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure (HF), CAD, and CVD5,6,12. However, studies have rarely examinined the association between SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with CVD. This study examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to evaluate the association between SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with CVD.

Materials and methods

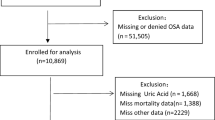

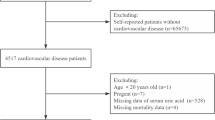

Study population

The NHANES, a thorough survey that represents health and nutrition conditions across the United States, provided the data for this study (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx). This study adhered to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology guidelines. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board approved the NHANES. Based on NHANES data, 1999–2018, we examined the association between SUA and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved the research protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent. The following patient groups listed below were excluded from the study: those younger than 20 years of age, those who were pregnant, those for whom more than 50% of the data were missing, those whose SUA level data were missing, those whose mortality data were missing, and those for whom covariates data were missing. Figure 1 shows the selection procedure. The final research population consisted of 4 308 individuals.

Data collection

Definition of CVD

According to the NHANES dataset, the presence of CVD was identified through participants’ self-reported history of congestive heart failure, angina, heart attack, CAD, or stroke.

Covariates

Based on previously published research, the analysis included the following covariates: age; sex; race and ethnicity; level of education attained; marital status; family income; body mass index (BMI); diabetes, vigorous physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and hypertension statuses; total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), fasting blood glucose (FPG) and glycohemoglobin levels; and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)13,14. Self-reported race and ethnicity data were gathered for the NHANES dataset using survey responses about racial background and Hispanic ethnicity. Four racial and ethnic categories were used to classify participants in accordance with NHANES conventions: Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican–American, and Others. Three categories were used to categorize educational attainment: below 9th grade, 9th to 12th grade, and beyond 12th grade. There were two categories for marital status: independent living (including widowed, divorced, separated, and never married people) and married or cohabiting. Following the criteria utilized by U.S. government entities for reporting NHANES data on dietary and health metrics15, family income was divided into three categories using the family poverty income ratio: low income (≤ 1.3), medium income (> 1.3 to 3.5), and high income (> 3.5). Physical activity (PA) was divided into two groups: vigorous activity (metablolic equivalents [MET] ≥ 48) and non-vigorous activity (MET < 48). PA was calculated using the following formula:

Smoking status was divided into three categories: never smokers, current smokers, and former smokers. Participants who had smoked even 100 cigarettes during their lifetime were considered never smokers; those who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in the past and reported smoking either some days or every day at the time of the interview were considered current smokers; and those who had smoked more than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime but did not smoke currently were considered former smokers. Alcohol consumption status was divided into two categories: non-drinkers and drinkers. The survey question "Have you had at least 12 drinks of any type of alcoholic beverage in the last year?" was used to establish alcohol consumption status. Participants who responded "yes" were classified as alcohol drinkers. Hypertension was diagnosed as a history of physician-diagnosed hypertension, an average systolic blood pressure of ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 80 mmHg16, or current use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes was diagnosed based on a history of physician-confirmed diabetes, a hemoglobin A1c level ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, 2-h oral glucose tolerance test blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or current use of antidiabetic medication or insulin17.

Clinical outcomes

This study's main outcome assessment included all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. According to the NCHS Codebook for the 2019 Public-Use Linked Mortality Files, we recognized all-cause mortality when MORTSTAT was set at 1.To define CVD fatalities, we used the International Statistical Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes. Cardiovascuar mortality was defined as death caused by a cardiac (UCOD_LEADING ICD = 001) or cerebrovascular illness (UCOD_LEADING ICD = 005). Beginning on the examination date, the follow-up period lasted until the individual passed away or the mortality monitoring period ended on December 31, 2019, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed of the data gathered for each subject. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean with standard deviation or median and interquartile range, while categorical variables are shown as counts and percentages. Using the χ2 test, one-way analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis test, respectively, statistical comparisons were made of continuous variables that were categorical, normally distributed, and non-normally distributed. Based on the lowest mortality risk, Quintile 4 (6.2–7.2 mg/dL) was designated as the reference group in an exploratory study.

We utilized Cox proportional hazards regression to perform four different multivariate models. SUA level was all that was included in the crude model. Adjusted factors with values of P < 0.1 were selected for the univariate analysis based on prior research and clinical limitations. Adjusted model I included age, sex, race, education, marital status, and family income, whereas Adjusted model II added adjustments for BMI, vigorous exercise, smoking, drinking, hypertension, and diabetes. Adjusted model III also included modifications for TC, HDL-C, and eGFR. The initial analysis used standardized Kaplan–Meier curves to determine survival rates. The connection between SUA level and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was studied next using multivariate-adjusted Cox limited cubic spline regression models and a generalized additive model to explore potential non-linear associations. We used two piecewise linear regression models to explain differences in connections around the inflection point in cases in wich non-linear correlations were identified. The inflection point value was identified by evaluating every possible value and choosing the inflection point with the highest chance.

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), sex (male or female), race (Non-Hispanic White or others), education level (less than 12th grade or more than 12th grade), marital status (married or living with partners or living alone), and family income (low, medium, or high). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Participants for whom more than 50% of the values were missing for TG, LDL-C, and FPG were included in sensitivity analyses to evaluate the validity of our results. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing), the survey package version 4.1-1, and the Free program Foundation statistics program version 1.9.2. To establish statistical significance, all tests used a two-sided values of P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline participant characteristics

A total of 1846 fatalities, 42.8% of the cases, were attributable to all causes throughout the course of the median 80-month follow-up. Of these deaths, 759 (17.6% of cases) were associated with cardiovascular mortality, which includes cardiac and cerebrovascular disorders (Table 1). Table 1 presents the baseline patient characteristics that are grouped according to SUA level (Q) quartiles: Q1, ≤ 4.5 mg/dL; Q2, 4.6–5.4 mg/dL; Q3, 5.5–6.1 mg/dL; Q4, 6.2–7.2 mg/dL; and Q5, ≥ 7.3 mg/dL. Individuals in the higher SUA were more likely to be male, be older, be Non-Hispanic Black, have a medium family income, have a higher BMI, engage in less intense PA, be current smokers, not drink alcohol, have a lower eGFR and HDL-C, and have a higher prevalence of comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension. Both all-cause mortality rates (35.2% vs. 42% vs. 39.3% vs. 40.4% vs. 55.8%; P < 0.001) and cardiovascular mortality rates (13.8% vs. 16.6% vs. 15.9% vs. 17.0% vs. 24.1%; P < 0.001) gradually increased as SUA level increased.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves of all‑cause and cardiovascular mortality according to SUA

There were 1846 cases of all-cause mortality and 759 cases of cardiovascular mortality over the median 80-month follow-up. Figure 2 shows the death rates for the various SUA level groups. Among the total study population, there was a noticeable difference in mortality between these groups (all-cause mortality: P < 0.0001, the log-rank test; cardiovacular mortality: P < 0.0001, the log-rank test) (Fig. 2A,B).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. SUA quartile (Q): Q1: ≤ 4.5; Q2: 4.6–5.4; Q3: 5.5–6.1; Q4: 6.2–7.2; Q5: ≥ 7.3. A Kaplan–Meier analysis for mortality among dietary niacin intake groups in (A) all-cause mortality, (B) cardiovascular mortality. SUA, serum uric acid.

Associations of SUA with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

The Cox proportional hazard analysis findings demonstrated a strong correlation between SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality when SUA was considered as a continuous variable in the unadjusted model (all-cause mortality: hazard ratio [HR] [95% confidence interval, 1.15 [1.12, 1.18], P < 0.001; cardiovascular mortality: 1.18 [1.13, 1.23], P < 0.001) and all adjusted models (all-cause mortality: Adjusted model I: 1.10 [1.07, 1.13], P < 0.001; Adjusted model II: 1.09 [1.05, 1.12], P < 0.001; Adjusted model III: 1.06 [1.02, 1.11], P < 0.001; Cardiovascular mortality: Adjusted model I: 1.13 [1.08, 1.18], P < 0.001; Adjusted model II: 1.10 [1.05, 1.15], P < 0.001; Adjusted model III: 1.07 [1.02, 1.13], P < 0.001) (Table 2). The association between classified SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was examined using a multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis. In all models, compared with group Quintile 4, the HR of Quintile 5 in the differrent models were 1.58 (1.38–1.80), 1.48 (1.29–1.69), 1.39 (1.21–1.59), 1.32 (1.15–1.52) (all P < 0.05) for all-cause mortality and 1.62 (1.32–1.99), 1.53 (1.24–1.88), 1.39 (1.13–1.72), 1.32 (1.07–1.63) (all P < 0.05) for cardiovascular mortality (Table 2), respectively. As the multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed a non-linear connection between baseline SUA level and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, restricted cubic splines analysis was used for further investigation. Adjusted restricted cubic spline plots showed non-linear associations between SUA and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (both P < 0.05) (refer to Fig. 3).

Association between SUA and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. (A) all-cause mortality, (B) cardiovascular mortality. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted for age, gender, race, education, marital status, family income, BMI, vigorous activity, smoking, drinking, hypertension, antihypertensive drugs, hypoglycemic agents, UA-lowering drugs and diuretics, diabetes, TC, HDL-C, glycohemoglobing, eGFR. SUA serum uric acid, BMI body mass index, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The inflection point analysis

In the inflection point analysis, the HR (95% CI) for all-cause mortality was 0.9912 (0.9098–1.0798) (P = 0.8392) for patients with an SUA level < 6.127 mg/dL, and 1.146 (1.078–1.217) (P < 0.001) for patients with an SUA level ≥ 6.127 mg/dL within the CVD cohort (Table 3). This indicated that, at an SUA level were < 6.127 mg/dL, there was no discernible correlation between SUA level and all-cause mortality. For every 1 mg/dL increase in SUA, there was a 14.6% increase in the probability of all-cause mortality at an SUA level were ≥ 6.127 mg/dL in the CVD population. Similarly, the HR for cardiovascular mortality was 0.965 (0.831–1.121) (P = 0.6432) at an SUA level < 5.938 mg/dL, and 1.123 (1.03–1.225) (P = 0.0085) at an SUA level ≥ 5.938 mg/dL within the CVD cohort (Table 3). This indicated that, at an SUA level were < 5.938 mg/dL, there was no discernible correlation between SUA level and cardiovascular mortaliy. For every 1 mg/dL increase in SUA, there was a 12.3% increase in the probability of cardiovascular mortality at an SUA level ≥ 5.938 mg/dL in the CVD population.

Subgroup analysis of the association between SUA level and all‑cause and cardiovascular mortality

To assess the impact of SUA level on primary outcomes, the data were stratified by age, sex, race, education level, marital status, and family income (Figs. S1, S2). No significant interactions found in any of the groupings (all-cause mortality: P for interaction = 0.06 to 0.834; cardiovascular mortality: P for interaction = 0.089 to 0.747). Notablely, the results indicated that high SUA level are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in male patients with CVD, whereas there is no significant association in female patients with CVD.

Sensitivity analysis

Variables for which more than 50% of the values were missing, such as TG, LDL-C, and FPG, were eliminated from analysis. These factors were used into the sensitivity study. There were 2 422 cases of all-cause mortality and 997 cases of cardiovascular mortality following multiple interpolations. SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality were consistently correlated. A significant correlation was found between SUA level and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the crude model (all-cause mortality: HR (95% CI), 1.14 (1.11–1.17), P < 0.001; cardiovascular mortality: 1.17 (1.13–1.22), P < 0.001) and all adjusted models (all-cause mortality: Adjusted model I: 1.09 (1.07–1.12), P < 0.001; Adjusted model II: 1.08 (1.05–1.11), P < 0.001; Adjusted model III: (1.03–1.09), P < 0.001; cardiovascular mortality: Adjusted model I: 1.12 (1.08–1.17), P < 0.001; Adjusted model II: 1.10 (1.06–1.15), P < 0.001; Adjusted model III: 1.09 (1.04–1.14), P < 0.001 (Table S1). The multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis examined the relationship between categorized SUA and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality after multiple interpolations. In all models, compared with group Quintile 4, the HR of Quintile 5 of the differrent models were 1.58 (1.40–1.77), 1.47 (1.31–1.65), 1.40 (1.24–1.58) and 1.36 (1.20–1.53) for all-cause mortality and 1.64 (1.37–1.96), 1.52 (1.27–1.84), 1.41 (1.17–1.69), and 1.35 (1.12–1.62) for cardiovascular mortality (Table S1), respectively.

Discussion

Our research found that, among individuals with CVD, a higher SUA level was associated with an increased risk of mortality from all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The connection between SUA level and mortality followed a non-linear pattern for overall mortality, with a major inflection point at about 6.127 mg/dL, and a non-linear pattern for cardiovascular mortality, with a notable inflection point at around 5.938 mg/dL. Both subgroup and sensitivity analyses indicated a substantial link between a higher SUA level and an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Several recent studies of NHANES datasets reported a non-linear connection between SUA and mortality risk in several populations at high risk for CVD, but the results differed greatly. In individuals with hypertension, Hao et al. observed a U-shaped connection between SUA levels and both total and cardiovascular mortality after completely accounting for possible variables. According to their research, individuals with low UA level (< 3.5 mg/dL) had a considerably higher risk of stroke, while those with high UA level (> 7.5 mg/dL) were at significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality18. Li et al. consistently found that, in individuals with diabetes, elevated SUA level were linked with higher risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Their retrospective analysis showed that the highest SUA had an the HR (95% CIs) of 1.28 (1.03–1.58) for all-cause mortality and 1.41 (1.03–1.94) for CVD mortality, while a meta-analysis of available cohort studies showed that for each 1 mg/dL increment in SUA level, the risks of all-cause and CVD mortality increased by 8% and 5%, respectively, among patients with diabetes14. Lihua et al. assessed the optimal levels of SUA in patients with hyperlipidemia and found that SUA showed a U-shaped relationship with all-cause mortality in both males and females. A threshold effect analysis revealed that overall, an average SUA level of 6.3 mg/dL (6.5 mg/dL in males, 6.0 mg/dL in females) may be safe with respect to patient survival13. Zhening et al. discovered that elevated SUA level were non-linearly correlated with the long-term mortality risk among patients with MAFLD patients and strongly correlated with an increased risk of MAFLD. A high SUA level (> 6.7 mg/dL) was linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular death in men, whereas a low SUA level was linked to an increased risk of cancer-related mortality. An SUA level > 5.5 mg/dL was linked to a higher risk of cancer-erlated and cardiovascular mortality in females19. However, very little research has examined the relationship between SUA and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with CVD, particularly analyses of NHANES data.

In contrast to earlier research, an L-shaped connection between UA and overall and CVD mortality was seen in the present study's population of patients with CVD. Interestingly, contrary to earlier reports, we discovered that there was an increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients with CVD at an SUA ≥ 5.938 mg/dL and an increase in all-cause mortality at an SUA ≥ 6.127 mg/dL. The reasons for the variations in curve shapes and values might be partially attributable to variations in study populations, clinical features, sample size, grouping approach, and confounding factor correction. Our study provides a unique opportunity to investigate the possible link between SUA levels and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among patients with CVD. This study’s findings may be foundational for future research into the role of SUA in increasing mortality risks.

Among patients with CVD, an L-shaped pattern was noted in the link between SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular moratlity. Our study included participants with CVD; however, the inclusion and exclusion criteria may have excluded high or low SUA instances, which might explain why it did not form a U-shaped curve. More precisely, at an SUA level > 6.127 mg/dL, there is a 14.6% increase in risk of all-cause mortality for every 1 mg/dL increase in SUA level but no significant link at an SUA level < 6.127 mg/dL. Additionally, we observed a similar pattern in the risk of cardiovascular mortality: at an SUA level > 5.938 mg/dL, there is an 12.3% increase in risk of cardiovascular mortality for every 1 mg/dL increase in SUA level. The current statistical data analysis suggests that a high SUA may contribute to an increased in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality rates among patients with CVD. A subgroup analysis revealed no significant interactions in various subgroups based on age, sex, race, education, marital status and family income. However, we found high SUA level are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in male patients with CVD, whereas there is no significant association in female patients with CVD according to subgroup analysis. This is consistent with some previous research20,21. But the underlying mechanism needs further study. Blood lipid and glucose levels are risk factors for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among patients with CVD. Variables for which more than 50% of values were missing, such as TG, LDL-C, and FPG, were eliminated from this study's analysis. To test this study's robustness, we included these factors in the sensitivity analysis. The sensitivity analysis revealed that a higher SUA level increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CVD group after repeated imputations of missing data, whether as a continuous or a categorical variables. The results of the sensitivity analysis were consistent with those of the multi-factor regression analysis.

While the exact mechanism underlying hyperuricemia and CVD mortality is unknown, the following are some possibilities. First, endothelial dysfunction is the primary cause of CVD. Second, an elevated UA may lead to endothelial dysfunction by elevating oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory factor levels. Third, urate is easily deposited in the vascular wall, which reduces nitric oxide generation in arterial endothelial cells and inhibits vasodilation22. Fourth, hyperuricemia not only directly results in LDL-C oxidation, it also increases the generation of oxygen free radicals, which in turn can lead to LDL cholesterol peroxidation23. Fifth, UA can cause endothelial dysfunction, increasing intracellular expression and aldose activity. Sixth, there is evidence that soluble UA may directly contribute to inflammation by inducing vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells to produce more monocyte chemoattrachtant protein-1 and C-reactive protein24,25, thus favouring the development of atherosclerosis26. Seventh, UA triggers the production of the inflammatory molecules interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, transcription nuclear factor k-B cascade, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-127. Eighth, along with the production of interleukin-8 and angiopoietin-2, soluble UA can induce the release of Weibel-Palade bodies28. And finally, UA may encourage arterial wall stiffness by causing an inflammatory state and encouraging vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation24.

Advantages and limitations

Here we investigated the relationship between SUA levels and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among patients with CVD. This study has several advantages. First, our inclusion of a nationally representative sample allows us to generalize the findings to the entire US population, over a long-term follow-up period of up to 6.5 years (median follow-up time) and a low frequency of mismatched data in the NHANES-associated mortality file. Second, because of the comprehensive data obtained from the NHANES, we were able to account for potential confounding effects caused by a variety of demographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors. Third, we used multiple interpolations to reduce the bias associated with missing data. In the sensitivity analysis, we adjusted for TG, LDL-C, and FPG, which were not included in the model, and discovered that the results were consistent. However, there are several limitations to this study. First and foremost, because this was a retrospective cohort research, we were unable to draw causal conclusions. Second, because NHANES participants reflect the US population, the results may not be applicable to population of other ethnicities or nations; therefore, prospective studies of various ethnicities are required to corroborate these findings. Third, while the mortality data were longitudinal, characteristics such as SUA level were available only available at baseline, which may not reflect typical levels during the long-term follow-up. Fourth, the current NHANES analysis did not include any follow-up data other than mortality, which might have led to incorrect diagnosis of brain and cardiac conditions and unknown changes in the variables during follow-up. Finally, despite adjusting for several potential confounding variables, we were unable to eliminate all residual confounding variables.

Conclusions

Finally, in this population of patients with CVD, SUA level were significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. An L-shape correlation was found between SUA level and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, with inflection points at 6.127 mg/dL and 5.938 mg/dL, respectively.

Data availability

Te datasets generated and analyzed for the current study are available in the NHANES database. More information about the NHANES can be obtained at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Force, U. S. P. S. T. et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 328, 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.13044 (2022).

Zimmet, P., Shaw, J. & Alberti, K. G. Preventing Type 2 diabetes and the dysmetabolic syndrome in the real world: A realistic view. Diabet. Med. 20, 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01052.x (2003).

Zhao, D., Liu, J., Wang, M., Zhang, X. & Zhou, M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: Current features and implications. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0119-4 (2019).

From the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, A. S. o. N. C. et al. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int. J. Stroke 13, 612–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493018778713 (2018).

El Ridi, R. & Tallima, H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: A review. J. Adv. Res. 8, 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2017.03.003 (2017).

Choi, H. K., Atkinson, K., Karlson, E. W., Willett, W. & Curhan, G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035700 (2004).

Major, T. J., Topless, R. K., Dalbeth, N. & Merriman, T. R. Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: Meta-analysis of population based cohorts. BMJ 363, k3951. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3951 (2018).

Hao, Y. et al. Uricase and horseradish peroxidase hybrid CaHPO(4) nanoflower integrated with transcutaneous patches for treatment of hyperuricemia. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 15, 951–965. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2019.2752 (2019).

Singh, G., Lingala, B. & Mithal, A. Gout and hyperuricaemia in the USA: prevalence and trends. Rheumatology (Oxford) 58, 2177–2180. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez196 (2019).

Freilich, M., Arredondo, A., Zonnoor, S. L. & McFarlane, I. M. Elevated serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A review and potential therapeutic interventions. Cureus 14, e23582. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.23582 (2022).

Culleton, B. F., Larson, M. G., Kannel, W. B. & Levy, D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: The Framingham Heart Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 131, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00003 (1999).

Furuhashi, M. New insights into purine metabolism in metabolic diseases: Role of xanthine oxidoreductase activity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 319, E827–E834. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00378.2020 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. U-shaped association of serum uric acid with all-cause mortality in patients with hyperlipidemia in the United States: A cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1165338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1165338 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in diabetes. Diabetes Care 46, 425–433. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-1339 (2023).

Dwyer, J., Picciano, M. F. & Raiten, D. J. Food and dietary supplement databases for what we eat in America-NHANES. J. Nutr. 133, 624S-634S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.2.624S (2003).

Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71, e13–e115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 (2018).

Ma, X. et al. Triglyceride glucose index for predicting cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-020-01006-7 (2020).

You, H., Chen, K., Han, P., Yue, C. & Zhao, X. U-shaped relationship between cardiovascular mortality and serum uric acid may be attributed to stroke- and heart-specific mortality, respectively, among hypertensive patients: A nationally representative cohort study. Med. Sci. Monit. 27, e928937. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.928937 (2021).

Liu, Z., Wang, Q., Huang, H., Wang, X. & Xu, C. Association between serum uric acid levels and long-term mortality of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: A nationwide cohort study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-00997-z (2023).

Chang, D. Y., Wang, J. W., Chen, M., Zhang, L. X. & Zhao, M. H. Association between serum uric acid level and mortality in China. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 134, 2073–2080. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001631 (2021).

Fu, K. et al. Gender differences in the relationship between serum uric acid and the long-term prognosis in heart failure: A nationwide study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02214-1 (2024).

Papezikova, I. et al. Uric acid modulates vascular endothelial function through the down regulation of nitric oxide production. Free Radic. Res. 47, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2012.747677 (2013).

Wu, G. J., Han, Y. L. & Wang, X. Z. Research Progress on the relationship between hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease. Adv. Clin. Med. 21, 216–217 (2023).

Kanellis, J. et al. Uric acid stimulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production in vascular smooth muscle cells via mitogen-activated protein kinase and cyclooxygenase-2. Hypertension 41, 1287–1293. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000072820.07472.3B (2003).

Kang, D. H., Park, S. K., Lee, I. K. & Johnson, R. J. Uric acid-induced C-reactive protein expression: Implication on cell proliferation and nitric oxide production of human vascular cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 3553–3562. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2005050572 (2005).

Singh, S. K., Suresh, M. V., Voleti, B. & Agrawal, A. The connection between C-reactive protein and atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 40, 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890701749225 (2008).

Johnson, R. J., Rodriguez-Iturbe, B., Kang, D. H., Feig, D. I. & Herrera-Acosta, J. A unifying pathway for essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 18, 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.035 (2005).

Kuo, M. C. et al. Ischemia-induced exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies mobilizes stem cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 2321–2330. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007111200 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Jie Liu of the Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Chinese PLA General Hospital, for his statistical help, research design discussions, and manuscript suggestions.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chinese central government, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, and the Jilin Province Education Department's Science and Technology Project (JJKH20201078KJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to this study and qualify as authors. Authors’ roles: study conception and design (Z.-K.S., D.-Y.D., H.-D.W.); data collection ((Z.-K.S., D.-Y.D.), data analysis ((Z.-K.S., D.-Y.D.); interpretation of results (all authors); drafting of manuscript (H.-D.W.); critical review of the manuscript (all authors).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Z., Deng, D. & Wu, H. Association of serum uric acid to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 14, 21808 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72527-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72527-4