Abstract

This paper proposes an improved hybrid algorithm for automated guided vehicles (AGVs) in port environments based on the concept of key obstacles for the JPS and DWA algorithms. Given the complexity of the port environment and the abundance of obstacles, the traditional heuristic function of the JPS algorithm is improved by adding the key obstacle heuristic function. Simultaneously, improvements are made to the evaluation function of the traditional DWA algorithm, where the braking distance is segmented into key obstacle distance and non-key obstacle distance, utilizing the concept of key obstacles. Simulation experiments are conducted using Matlab to demonstrate the effectiveness of the improved algorithm. Moreover, the performance of the hybrid algorithm is compared with five mainstream algorithms in a real simulated port environment, and the final results show the significant enhancement of this paper’s algorithm in several key performance metrics. Thus, this study provides a feasible strategy for improved path planning efficiency for AGV in the port environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the world has entered an era of global economic integration, with a significant increase in international trade between countries1. Approximately 80% of transnational trade now occurs via maritime routes, highlighting the pivotal role that ports play in facilitating country-to-country trade2. Nations are increasingly prioritizing the development of port infrastructure to enhance their competitive edge in the global market. For example, China’s 2013 launch of the “Belt and Road” initiative underscores the importance of the “Maritime Silk Road” as a vital trade corridor connecting nations3. In 2016, trade on sea routes accounted for 90% of African total trade, and the economic benefits generated by trade in ports have become deeply bound up with the well-being of the African population4. Based on this economic environment, establishing a reliable and efficient port trading system is crucial for the economic development of port cities and their countries. Especially for developing countries, which are highly dependent on global trade for their economic growth, building smart ports is urgent5.

In assessing the efficiency of a port, various evaluation indicators are considered, such as size, geographical location, equipment condition, and workforce size. Among these indicators, the intelligence and automation level of the port are crucial factors for evaluation6. Among the many automated devices, Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) are highly valued by researchers because of their ability to autonomously perform braking, turning, navigation, and handling tasks without human intervention.

In order to fulfill the various tasks in the port, AGV needs to plan out a path that is safe, feasible, and time-efficient7. AGV path planning is typically segmented into two key stages based on the detailedness of the map information: global path planning and local path planning8. Global path planning involves charting the shortest path for the AGV, given a known map layout. There are various classical algorithms for the global planning path, such as the Dijkstra algorithm9, the BFS algorithm10, the A* algorithm, the JPS algorithm, etc. Of these, Dijkstra’s algorithm, although reasonable in determining the shortest path, has lagged in its search efficiency and has therefore decreased in use in recent years; in contrast, the BFS algorithm addresses the efficiency issue but BFS algorithm cannot guarantee that the end result is the shortest path11. The A* algorithm integrates the strengths of both Dijkstra algorithm and BFS algorithm. This algorithm significantly enhances search efficiency and ensures that the path identified is the shortest. This makes the A* algorithm one of the most critical global planning algorithms today12. The JPS algorithm is based on the A* algorithm, ignoring unnecessary nodes and focusing on key nodes, which is superior to the A* algorithm in terms of search efficiency13. Many researchers have also improved these algorithms for these algorithms in recent years, for example, Zhang et al. dynamically adjusted the AGV turning process by judging the angle of the AGV when turning and improved the A* algorithm based on this idea, reducing the number of turns in the pathfinding process to make the path smoother14. Sun et al. combined the octagonal search method with the Dijkstra algorithm to significantly reduce the probability of collision with obstacles during AGV travel15. Zhang et al. proposed the “Congestion Control” strategy, combining it with the JPS algorithm to solve the congestion problem during AGV handling16.

In addition to global planning algorithms, local path planning algorithms are also extremely important in the entire path planning process, as they allow AGV to avoid obstacles that suddenly appear during driving and deal with moving obstacles. Local path planning algorithms mainly include the DWA algorithm17, artificial potential field algorithm18 combined with deep learning algorithm, etc. To improve path planning for mobile robots, many researchers have optimized local path planning algorithms; for example, Wu et al. further refined the evaluation function in the DWA algorithm to improve the precision of path planning19. Li et al. split the DWA evaluation function into two segments based on the distance between the obstacle and the front and rear ends of the AGV, which improves the precision of path planning and safety during travel20.

Unfortunately, despite the abundance of research on AGV path planning, path planning algorithms for AGV in port environments still have many shortcomings. For example, Hao et al. utilized the ant colony algorithm to reduce obstacle collisions during AGV path planning21. However, no significant enhancements were observed in path planning time and path length. On the other hand, Meng et al. improved path planning speed employing the artificial fish swarm algorithm22, while Tang et al. minimized redundant nodes in the path planning process through the geometric A* algorithm, leading to improved path planning speed23. Zhong et al. solved the shortest distance model with the help of Dijkstra’s algorithm to solve the problem of vehicle congestion and conflicts in port24. Yue et al. combined the Dijkstra algorithm with the Q-Learning algorithm to reduce the probability of path conflicts between multiple AGVs in port25. However, the above mentioned studies have only improved the global path planning algorithm. Based on these issues, it remains to be verified whether there is a real improvement in the local obstacle avoidance capability and the integrated path planning efficiency of AGVs in the port environment.

A practical path planning algorithm should have short search and navigation times, minimize path lengths and turn frequency, generate smooth paths, and be able to avoid sudden and dynamic obstacles while finding a path. Addressing these requirements, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

Firstly, the key obstacle was introduced based on the heuristic function of the traditional JPS algorithm, which is modified to reduce the search space and the number of collisions with obstacles.

-

2.

Considering that AGV can fall into local optima when using the traditional DWA algorithm for dynamic obstacle avoidance, this paper subdivides the braking distance evaluation function into two parts based on whether the obstacle is a key obstacle, effectively solving the problem of the DWA algorithm potentially falling into local optima and further controls the safe distance between the AGV and the obstacle.

-

3.

The improved JPS algorithm and the DWA algorithm are merged and applied to planning the AGV path in the port environment. After comparing with other mainstream algorithms, significant improvements in navigation time, number of turns, number of collisions with unknown obstacles, and navigation path were found.

Kinematic modeling

Kinematic modeling is conducted based on the following assumptions:

-

1.

When AGV is in turning motion, it is considered a rigid body, mainly moving in a two-dimensional plane, and the wheels do not deform due to contact with the ground.

-

2.

The motion of AGV is purely rolling without any occurrence of tangential sliding.

Based on the above two assumptions, the kinematic model of AGV is constructed as shown in Fig. 1a. A coordinate system \(O-XY\) is established with the starting point of the AGV movement, and an AGV coordinate system \(C-XcYc\) is established with the geometric center of the AGV, where \(\theta \) represents the angle of direction. The constraint equations of this simplified model are as follows:

The kinematic model of the AGV chassis can be represented by the following equation:

Based on the simplified differential kinematic model, Eqs. (3 and 4) are defined as follows:

Where v is the linear velocity, \(\omega \) is the angular velocity, according to Eqs. (3 and 4), \({\dot{q}}\) can be expressed as Eq. (5).

According to the rigid body kinematic model, the linear velocity and angular velocity at the geometric center of the simple rigid body model can be determined:

According to Eq. (6), we can determine the kinematic law of the velocity change relative to the position of the AGV differential, as shown in Eq. (7).

In practical problems, discretizing Eq. (7) is often necessary. The discretized model is shown in Fig. 1b. According to this model, the pose of the AGV is calculated, and the distance moved by the AGV within \(\Delta t\) is determined as:

The change in heading angle of the AGV relative to the initial position is:

As a result, the position of the AGV is:

The movement of the AGV during this short period can be regarded as arc motion, with the radius of the arc being:

At this point, the pose of the AGV is:

When \(\Delta \theta _k=0\), the movement time of the AGV is very short. At this time, the movement path of the AGV can be approximated as a branch line, and the posture of the AGV at this time is shown in Eq. (13).

The main parameters of the AGV used in this paper are shown in Table 1.

The optimal path problem

Traditional path planning algorithms focus mainly on finding the shortest path. In Fig. 2, the red numbers indicate the length of movement between neighboring points. To illustrate, if one intends to travel from point 1 to point 7, the primary concern is the path incurs the least cost. That is, traditional global path planning algorithms solve the problem of:

where \(L_{path}\) represents the path length.

However, the shortest path is often not the optimal path. For example, the shortest path often results in the AGV traveling close to obstacles, but the AGV itself has a certain volume, and this kind of path is not feasible in practical applications, or a path although the shortest distance needs to turn frequently, AGV in the process of turning time is not taken into account. Especially in port environments with many obstacles and complex environments, these problems can greatly affect the efficiency of AGVs and may even lead to safety problems. Some variables are listed to make the actual situation more compatible with the port environment studied in this paper, as shown in Table 2.

With F as the objective function, the formula is as follows:

subject to:

where \(\alpha \),\(\beta \),\(\gamma \) are weighting coefficients, which can be adjusted according to specific needs, in a more efficiency-oriented port environment, shorter total journey time and safer travel process are more significant compared to shorter paths, so the weights of \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) can be appropriately increased.

JPS algorithm improvement

Traditional JPS algorithm

JPS algorithm, full name is Jump Point Search algorithm. It adds valuable nodes to the OpenList based on two specific rules26. The two rules are the Look Ahead Rule and the Jump Rule27. The basic idea revolves around sorting the cost of optional nodes around the current node, selecting the node with the lowest cost, and repeating the process until the destination point is reached. Its evaluation function is consistent with the A* algorithm, and the expression is as follows:

In Eq. (20), g(n) represents the actual cost of AGV from the starting point of the path to the current node n, and h(n) is the minimum estimated cost from AGV’s current node n to the destination point. Typically, h(n) is defined as the Manhattan distance from the starting node to the current node n, expressed as follows:

Improvements to the JPS algorithm

In the port environment, numerous fixed obstacles, such as large containers and operating equipment, differ distinctly from environments such as orchards or urban streets. Unlike the orderly arrangement of obstacles in orchards or the fixed positions of obstacles in urban streets, port terminals present obstacles diverse in shapes and complex arrangements. Moreover, due to the constant movement of cargo, the positions of these obstacles frequently change. As a result, global path planning in a port environment is computationally intensive. Therefore, it is imperative to reduce the computational complexity of the algorithm, improve the efficiency of path planning, and minimize collisions with obstacles to facilitate smoother navigation.

Key obstacle heuristic function

The heuristic function h(n) plays a dominant role in the traditional JPS algorithm. In the traditional JPS algorithm, the heuristic function h(n) is calculated based on the Manhattan distance from the AGV’s current node to the target node. As shown in Fig. 3, the traditional JPS algorithm considers most nodes on the path.

Based on this issue, this paper proposes a new heuristic function: the Key Obstacle Heuristic Function.

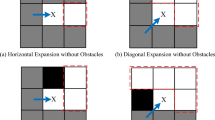

In Fig. 4a, black grids represent regular obstacles, and to get from the starting point to the target point, the AGV must pass through the brown grid. There are multiple feasible paths for the AGV to reach these key points. However, as shown in Fig. 3b, the traditional JPS algorithm must traverse most of the nodes to plan the path, which is too computationally intensive.

In reality, the AGV does not need to search all the nodes to plan a feasible path; it only needs to focus on the paths that must be traveled to reach the key points. As shown in Fig. 4b, the AGV that wants to arrive at the target point will inevitably pass through one or more of the red grids no matter which path it chooses, and the obstacles adjacent to these red grids are called “Key Obstacle.” Among the nodes adjacent to these key obstacles, we need to identify a node to ensure that the AGV can reach the target point safely and with a shorter path. For this purpose, we give the critical obstacle function K(O):

where the current coordinates is \((x_o,y_o)\), where the starting point coordinates are \((x_s,y_s)\) and the key point coordinates are \((x_k,y_k)\). Through Eq. (22), the key obstacle function values can be calculated for different nodes, and the node with the minimum value is selected. As illustrated in Fig. 4c, the yellow grid represents the node with the minimum K(O) value, and the red obstacle associated with this grid is considered the key obstacle. After identifying the key obstacle, the AGV only needs to directly reach the node with minimum cost near the key obstacle.

Once the key obstacle is determined, the AGV no longer needs to traverse to find useless nodes on the path from the starting point to the key point; it only needs to focus on the key obstacle. Similarly, when the AGV reaches the key point, the key obstacle for the next key point is determined similarly until it reaches the target point. The search area of the improved algorithm is shown in Fig. 5, which is significantly reduced compared to the traditional JPS algorithm in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 6a, the global path planned by the traditional JPS algorithm, while Fig. 6b depicts the global path planned by the JPS algorithm with the inclusion of key obstacle determination. Evidently, the improved path is smoother, with fewer turning points, lower planning costs, and adequate safety distance reserved when turning to avoid obstacles.

The pseudo code of the improved JPS algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

DWA algorithm improvement

Traditional DWA algorithm

The DWA algorithm is a local path planning algorithm that corrects the path. Sampling the linear and angular velocities of the AGV at each moment simulates the trajectories that the AGV could take under various combinations of velocities. It predicts potential new obstacles in \(\Delta t\) time. An evaluation function is used to choose the optimal trajectory for the locally re-planned path. In light of the actual circumstances, the pose sampling space of the AGV is restricted by its maximum and minimum linear velocities, angular velocities, motor power, and braking distance28.

Based on these constraints, by introducing an evaluation function to predict the next trajectory, the prediction of the velocity component at the next moment of the AGV can be realized, and the locally optimal path can be planned on this basis. The following equation can express the evaluation function:

In Eq. (23), \(heading(v,\omega )\) is used to evaluate the AGV’s heading deviation, \(dist(v,\omega )\) represents the minimum braking distance between the AGV and obstacles at a certain linear velocity and angular velocity, and \(velocity(v,\omega )\) denotes the sampled velocity. \(\alpha \),\(\beta \),\(\gamma \) are the weighting coefficients. These weighting factors can be adjusted to optimize the final planned path, allowing the algorithm to adapt to more different scenarios.

Optimisation of the evaluation function of the DWA algorithm

In the traditional DWA algorithm, the weight of \(dist(v,\omega )\) in the evaluation function determines the distance from the AGV to the nearest obstacle. In order to improve the obstacle avoidance performance of the DWA algorithm in complex environments and make it more suitable for port environments, and avoid falling into local optima, this paper subdivides \(dist(v,\omega )\) in the evaluation function by incorporating the concept of key obstacles, dividing it into \(dist \_ a(v,\omega )\) for evaluating the distance between the AGV and non-key obstacles, and \(dist \_ b(v,\omega )\) for evaluating the distance between the AGV and key obstacles.

The coordinates \((x_t, y_t)\) represent the predicted coordinates of the DWA algorithm at time t, while \((x_s, y_s)\) represents the coordinates of non-key obstacles, and R is the length of half of the longest side of the robot chassis. To further ensure that the robot does not collide with obstacles, a space of 0.2R is reserved as the safety distance.

The coordinates \((x_k, y_k)\) is the coordinates of the key obstacle. After subdividing \(dist(v,\omega )\), different weights can be assigned to key obstacles and non-key obstacles based on the actual environment. Utilizing the results of global path planning to guide local path planning further helps to avoid falling into local optima.

The evaluation function of the optimized DWA algorithm is as follows:

Implementation of the hybrid algorithm

The improved JPS algorithm enables AGV to obtain optimal solutions in global path planning in port environments and perform well in static working environments. However, relying solely on a global planning algorithm may fail to avoid unknown obstacles in the environment promptly. On the other hand, although improving the DWA algorithm for path planning allows for obstacle avoidance in the environment, it lacks global planning capabilities. This means that relying solely on the DWA algorithm may lead to getting stuck in local optima, especially in environments with many obstacles, and may even result in path planning failure. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate these two algorithms, using the concept of key obstacles as a bridge, to blend the strengths of both approaches. Its flowchart is shown in Fig. 7.

Experimental results and analysis

Simulation experiment results and analysis

The port terminal environment features numerous obstacles with irregular shapes. The main thoroughfares are relatively clear, with numerous moving obstacles, among other characteristics29. Based on these conditions, the imitation port environment is built in reality, as shown in Fig. 8a. The grid map of the environment in Fig. 8a is created in Matlab, resulting in Fig. 8b.

As shown in Fig. 9, black blocks represent known obstacles, while blank areas represent movable areas. The start point is labeled “Start,” and the target point is labeled “Target.” The number of corners in the path can be considered as the number of turns and is marked with red dots. Compared with the traditional JPS algorithm, the improved JPS algorithm plans a path with fewer turns on the same map. The traditional JPS algorithm plans a path with 7 turns, while the improved JPS algorithm plans a path with only 4 turns.

While significantly reducing the number of turning points, collisions between AGV and obstacles during travel are also reduced. As shown in Fig. 10a, in the global path planned by the traditional JPS algorithm, the AGV may collide with the corners of obstacles at multiple locations. In contrast, these collision points are absent in Fig. 10b. The comparison in Table 3 shows that the improved JPS algorithm improves the navigation time by about 15.94%, reduces the number of turns by 42.85%, and also solves all the points where collisions may occur. The navigation cost becomes 10% longer; this is because the traditional JPS algorithm causes the AGV to drive or turn close to obstacles, which is unreasonable in practical applications. After all, it will lead to a collision between the AGV and the obstacles. In order to avoid this situation, AGVs are required to keep a certain distance from obstacles, which inevitably leads to a longer navigation path. This problem is solved by integrating with local path planning algorithms.

Simulate local path planning, selecting weight parameters for the traditional evaluation function (Eq. 23) as \(\alpha =0.2\), \(\beta =0.3\), \(\gamma =0.4\). For the improved evaluation function proposed in this paper (Eq. 26), the selected weight parameters are \(\alpha =0.2\), \(\beta =0.3\), \(\mu =0.15\), \(\gamma =0.3\).

To test the obstacle avoidance performance of traditional DWA and improved DWA algorithms in dynamic scenarios involving moving and unknown obstacles, build the simulation environment shown in Fig. 11a, yellow grid blocks represent moving obstacles. In contrast, gray grid blocks represent unknown obstacles that will not be recognized in the global path. This environment evaluates the differences in obstacle avoidance performance between traditional DWA and improved DWA algorithms.

The navigation process is shown in Fig. 11b, where Start represents the starting point, Target represents the target point, AGV position indicates the current position of the AGV, improved path is the optimal path obtained from the hybrid algorithm, and global path represents the globally planned path.

As shown in Table 4., with the same use of the JPS algorithm to plan the global path, the improved DWA algorithm improves navigation time by 22.14%, reduces the number of turns by 2, reduces the number of possible collisions with obstacles by 2, and reduces the navigational path by 17.36%. As can be seen in Fig. 11b, the conventional algorithm needs to select a longer path to bypass the moving obstacle due to inefficient navigation; it can be seen that improving the efficiency of navigation is crucial for path selection.

Results and analyses of physical experiments

A mapping command is issued to the AGV, and the startup file of the Gmapping algorithm is executed autonomously in ROS to construct a 2D map of the test environment and use laser SLAM to map the real environment illustrated in Fig. 8a. Figure 12b shows the AGVs used for the physics experiments. As shown in Fig. 12b. The black area represents the actual position of obstacles in reality mapped by Lidar, and the white area represents the passable area. The navigation map is shown in Fig. 12c, where “Start” is the starting point, and “Target” is the target point. Have a person walk randomly around the red area to simulate moving obstacles in the port.

The hybrid algorithm improved in this paper is compared with some mainstream algorithms currently used. The selected algorithms include the traditional A*+DWA hybrid algorithm, the traditional JPS+DWA hybrid algorithm, traditional RRT+DWA hybrid algorithm, bidirectional RRT+DWA hybrid algorithm30, and A*+traditional DWA hybrid algorithm with the obstacle coefficient K introduced(hereinafter referred to as A*+K+DWA)20. They are shown sequentially in Fig. 12d–h. The algorithm in this paper is shown in Fig. 12i.

In order to compare the differences between the algorithms more intuitively, some key information is differentiated by different colors. In Fig. 12 the green circle is the position where the AGV makes a larger turn, and the blue circle is the position where the AGV collides or rubs against the obstacles. The red path is the path the AGV has traveled, the pink path is the subsequent path planned by the global path algorithm, and the green path is the actual path planned by the hybrid algorithm.

From the path comparison of each algorithm in Fig. 12, it can be seen that the algorithm in this paper has improved in path length, path smoothness, number of turns, number of collisions, and other indexes compared to the previous ones. Among them, except for this paper’s algorithm and the A*+K+DWA algorithm, the other algorithms cannot bypass the moving obstacles in time because of the lack of search efficiency or path planning efficiency and have to choose a longer path. Compared with the A*+K+DWA, the algorithm in this paper has fewer turns and smoother paths.

Compare the navigation time, number of turns, number of collisions with obstacles, and navigation path for each algorithm. The results are summarized in Table 5. The percentage of performance improvement is shown in Table 6.

The experimental results indicate that the new algorithm proposed in this paper can meet the navigation requirements of AGV in port terminal environments. In comparison with several traditional and improved main algorithms, it can be observed that the algorithm proposed in this paper shows significant improvements in navigation time, number of turns, number of collisions with unknown obstacles, and navigation path compared to traditional and improved main algorithms. Optimization of the evaluation function significantly reduces navigation time, and the JPS algorithm is more suitable for environments with more complex obstacles than the A* and RRT algorithms. The improvement of the algorithm effectively reduces the number of turns and significantly shortens the navigation path. There is a general performance improvement of 20% to 30% in navigation time, with an increase of up to 38.57% compared to the traditional RRT+DWA hybrid algorithm. In addition, there is at least a 40% improvement in the number of turns, and collisions with unknown obstacles are reduced to zero, ensuring the safety of the AGV during travel. The improvement in navigation path ranges from 27 to 35%; this is largely due to the improved search efficiency and path smoothing of the algorithms in this paper, which allows the AGV to reach the target point faster without having to choose a longer path due to moving obstacles.

Summaries

In this paper, a hybrid algorithm is proposed for planning the route in the port environment based on key obstacles. The evaluation function and algorithmic flow of the JPS algorithm and the DWA algorithm are improved using the key obstacle concept proposed in this paper, and the improved algorithm in this paper is verified to be smoother on the path, with fewer turns and higher safety compared to the traditional algorithm by simulation experiments in Matlab. After the hybrid of the improved algorithms, physical experiments are carried out using a port environment built in reality, and comparing with five mainstream algorithms; it is verified that the algorithm of this paper has the advantages of shorter navigation paths, shorter navigation time, smoother paths, higher security, and better handling of moving obstacles in the port environment. However, there are still some unsolved problems in this paper; for example, this paper has not considered how to deal with the unevenness of the ground if it exists in the real environment and whether the experimental results in the 2D plane can be directly applied to the 3D harbor environment. These issues need to be further investigated.

Data availability

The availability of the raw data and code used in this study is limited. Since the data are provided by WHEELTEC, you can try to contact them at https://www.wheeltec.net/ to obtain the data. If you need data related to the results of the experiment,please contact Wenkai Xiong (6120220326@mail.jxust.edu.cn)

References

Ye, S., Qi, X. & Xu, Y. Analyzing the relative efficiency of China’s Yangtze river port system. Marit. Econ. Logist. 22, 640–660 (2020).

Millefiori, L. M., Zissis, D., Cazzanti, L. & Arcieri, G. A distributed approach to estimating sea port operational regions from lots of ais data. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 1627–1632 (IEEE, 2016).

Ziran, J., Chunfang, P., Huayou, Z., Chengjin, W. & Shilin, Y. Temporal and spatial evolution and influencing factors of the port system in Yangtze river delta region from the perspective of dual circulation: Comparing port domestic trade throughput with port foreign trade throughput. Transp. Policy 118, 79–90 (2022).

Ayesu, E. K., Sakyi, D., Arthur, E. & Osei-Fosu, A. K. The impact of trade on African welfare: Does seaport efficiency channel matter?. Res. Globalization 5, 100098 (2022).

Yau, K.-L.A., Peng, S., Qadir, J., Low, Y.-C. & Ling, M. H. Towards smart port infrastructures: Enhancing port activities using information and communications technology. Ieee Access 8, 83387–83404 (2020).

Karaś, A. Smart port as a key to the future development of modern ports. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 14, 27 (2020).

Zhong, M., Yang, Y., Dessouky, Y. & Postolache, O. Multi-AGV scheduling for conflict-free path planning in automated container terminals. Comput. Ind. Eng. 142, 106371 (2020).

Borges, C. D. B., Almeida, A. M. A., Júnior, I. C. P. & Junior, J. J. D. M. S. A strategy and evaluation method for ground global path planning based on aerial images. Expert Syst. Appl. 137, 232–252 (2019).

Dijkstra, E. W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy 287–290 (ACM Books, 2022).

Moore, G. E. Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Proc. IEEE 86, 82–85 (1998).

Wibowo, N., Widodo, C. & Adi, K. Implementing the shortest time route search algorithm in Semarang using the best first search method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 879, 012165 (2020).

Hart, P. E., Nilsson, N. J. & Raphael, B. A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 4, 100–107 (1968).

Harabor, D. & Grastien, A. Online graph pruning for pathfinding on grid maps. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 25, 1114–1119 (2011).

Zhang, D., Chen, C. & Zhang, G. AGV path planning based on improved a-star algorithm. In 2024 IEEE 7th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), vol. 7, 1590–1595 (IEEE, 2024).

Sun, Y., Fang, M. & Su, Y. AGV path planning based on improved Dijkstra algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1746, 012052 (2021).

Zhang, Y. & Huang, H. Check for updates multi-AGVS pathfinding based on improved jump point search in logistic center. In Algorithmic Aspects in Information and Management: 14th International Conference, AAIM 2020, Jinhua, China, August 10–12, 2020, Proceedings, vol. 12290, 358 (Springer Nature, 2020).

Lee, D. H., Lee, S. S., Ahn, C. K., Shi, P. & Lim, C.-C. Finite distribution estimation-based dynamic window approach to reliable obstacle avoidance of mobile robot. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 9998–10006 (2020).

Sang, H., You, Y., Sun, X., Zhou, Y. & Liu, F. The hybrid path planning algorithm based on improved a* and artificial potential field for unmanned surface vehicle formations. Ocean Eng. 223, 108709 (2021).

Wu, B. et al. Dynamic path planning for forklift AGV based on smoothing a* and improved DWA hybrid algorithm. Sensors 22, 7079 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Robot path planning navigation for dense planting red jujube orchards based on the joint improved a* and DWA algorithms under laser slam. Agriculture 12, 1445 (2022).

Hao, L., Ma, G. & Dong, J. Path planning method of anti-collision for the operation road of port cargo handling robot. J. Coastal Res. 103, 892–895 (2020).

Meng, X. & Li, X. Research on optimization of port logistics distribution path planning based on intelligent group classification algorithm. J. Coastal Res. 115, 205–207 (2020).

Tang, G., Tang, C., Claramunt, C., Hu, X. & Zhou, P. Geometric a-star algorithm: An improved a-star algorithm for AGV path planning in a port environment. IEEE access 9, 59196–59210 (2021).

Zhong, M. et al. Priority-based speed control strategy for automated guided vehicle path planning in automated container terminals. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 42, 3079–3090 (2020).

Yue, L. & Fan, H. Dynamic scheduling and path planning of automated guided vehicles in automatic container terminal. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 9, 2005–2019 (2022).

Aversa, D., Sardina, S. & Vassos, S. Path planning with inventory-driven jump-point-search. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. Interact. Digit. Entertain. 11, 2–8 (2015).

Harabor, D. & Grastien, A. The JPS pathfinding system. In In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Combinatorial Search, vol. 3 207–208 (2012).

Huang, P. et al. Deep-learning-based trunk perception with depth estimation and DWA for robust navigation of robotics in orchards. Agronomy 13, 1084 (2023).

Casaca, A. C. P. Simulation and the lean port environment. Maritim. Econ. Logist. 7, 262–280 (2005).

Liu, S., Zhang, Y., Duan, W. & Jia, S. Motion planning algorithm for orchard robots based on improved bidirectional RRT*. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 53, 31–39 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology and Conceptualization, G.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, G.Y. and W.X.; writing-review and editing, G.Y. and W.X.; software and validation, W.X; data curation and project administration,W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, G., Xiong, W. Port environmental path planning based on key obstacles. Sci Rep 14, 21757 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72530-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72530-9