Abstract

In recent years, chalcogenide perovskites have emerged as promising candidates with favorable structural, electrical, and optical properties for photovoltaic applications. This paper explores the structural, electronic, and optical characteristics of ABSe3 perovskites (where A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs; B = Si, Ge, Sn) in their triclinic crystallographic phases using density functional theory. The stability of these materials is ensured by calculating formation energies, tolerance factors (Tf), and phonon dispersion. The Eform values of all ABSe3 are negative, suggesting favorable thermodynamic stability. The Tf values range between 0.82 and 1.1, which is consistent with stable perovskites. The phonon dispersion analysis of the chalcogenide perovskites revealed no imaginary frequencies in any of the vibrational modes, confirming their stability. The electronic band structures and corresponding density of states are computed to unveil the semiconducting nature of the studied compounds. These perovskites are promising for high-performance solar cells due to their indirect bandgaps (Eg, 1.10–2.33 eV) and a small difference between these indirect and direct gaps (0.149–0.493 eV). The Eg values increase as the ionic radii of A-site elements increase (Li < Na < K < Rb < Cs). At the B-site, Si-based chalcogenides have the largest Eg values, followed by Sn-based and then Ge-based materials. Furthermore, optical properties such as the real part and imaginary part of the dielectric function, refractive index extinction coefficient, optical conductivity, absorption coefficient, reflectivity, and energy loss are predicted within the energy range of 0–50 eV. Several ABSe3 materials, particularly LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3, demonstrated optical properties comparable to both traditional and emerging materials, suggesting their potential for effective use in solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the increasing global energy use, and as currently available energy sources are mostly based on fossil fuels, researchers are increasingly focused on developing renewable energy resources1,2. Solar energy, a vital source of renewable energy, can be harnessed through thermoelectric and photovoltaic technologies. These technologies convert heat and light from the sun into electrical energy3. The selection of materials is crucial for determining their suitability in thermal applications (e.g., thermoelectric devices) and photoelectric applications (e.g., solar cells) due to their property dependence (conductivity, band gap)4.

Perovskite materials may play a crucial role in this regard because of their extraordinary physical properties such as magnetic, ferroelectric, optical, charge ordering, spin-dependent transport and high thermoelectric power5,6. Within the diverse perovskite family (oxide, halide, and chalcogenide)7,8,9,10,11,12,13, chalcogenide perovskites, with a general formula ABX3 (where A and B represent cations of different sizes and X is a chalcogenide element S, Se, or Te), are attracting attention for their potential in solar energy conversion due to their favorable structural, optical, and electronic characteristics. Oxide and halide perovskites have long been exhibiting remarkable properties for solar energy conversion14,15,16. For instance, various perovskite materials displayed promise in several technological applications. Compounds like A2NiMnO6 (A = La, Gd)17, Ca2NaIO618, Sr2NaIO618, RbPbBr319, RbPbI319, and Rb2NaCoX6 (X = Cl, Br, I)20 exhibit properties suitable for magneto-caloric refrigeration, photocatalysis, thermoelectric energy conversion, and other applications due to their favorable structural, electrical, optical, and transport characteristics. However, oxide perovskites often exhibit limitations for solar energy conversion due to their wide band gaps21. This limitation arises from the high electronegativity of oxygen, which typically results in bandgaps positioned in the ultraviolet (UV) region. On the other hand, halide perovskites suffer from toxicity, moisture, and thermal instability22.

Lead-based perovskites have attracted considerable interest for their outstanding optoelectronic properties, particularly in solar cell applications. However, the toxicity of lead raises significant environmental and health concerns, prompting researchers to explore lead-free alternatives5,11. The development of environmentally friendly lead-free perovskites solar cells has become crucial to realize their large-scale production. To address this challenge, several novel lead-free perovskite materials have been explored both computationally and experimentally23,24,25,26. A computational study using density functional theory (DFT) of ethylammonium tin chloride (C2H5NH3SnCl3) has shown that this material can exhibit favorable electronic band structure and optical properties, making it suitable for thermoelectric applications27. Recent computational studies, such as that by Riku et al.28, have identified lead-free ABX3 (A = Rb or Cs, B = Sn, Sr, or Ca, X = Cl, Br, or I) perovskites are ideal for solar cells and light-emitting diodes28. Sarker et al. demonstrate that NaGeX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, and I) is beneficial and non-toxic for solar cell applications29. DFT computation of KSnI3, KSn0.5Ge0.5I3, and KGeI3 demonstrate their capability as a functional layer in nontoxic perovskite solar cells30.

Chalcogenide perovskites offer superior environmental stability compared to halide perovskites, making them ideal for long-term applications like solar cells, where exposure to moisture and heat can degrade performance31. They are also composed of non-toxic elements, making them more environmentally friendly and safer for commercial use1,7,31. Chalcogenide perovskites can achieve high absorption coefficients, which enhances their efficiency as photoabsorbers32. Their covalent nature improves electronic and optical performance, leading to better charge transport and reduced recombination losses33. Additionally, they possess higher thermal and moisture stability than oxide perovskites, crucial for maintaining device performance31. Finally, chalcogenide perovskites offer tunable bandgap structures, optimizing their performance for applications like tandem solar cells23,33.

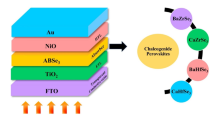

Recently, a diverse range of chalcogenide perovskites with interesting properties has been both experimentally verified and theoretically predicted31,34,35,36,37,38,39. Perera et al.40 reported the successful synthesis of several chalcogenide perovskites, including BaZrS3, CaZrS3, SrZrS3, and SrTiS3. These materials exhibit unique physical properties, such as being free of deep-level defects, which is beneficial for energy harvesting and other optoelectronic applications. Shaili et al. reported that synthesized CaSnS3 exhibits a suitable bandgap of 1.72 eV for optoelectronic applications41. SrZrS3 and SrZrSe3 may be employed as a photovoltaic absorber coating inside solar cells, as well as in energy conversion devices owing to their acceptable optical and thermoelectric properties42. Naincy et al. predicted the applicability of BaZrS3 and BaZrSe3 in energy conversion device fabrication43. Nishigaki et al. reported the synthesis of BaZrS3, SrZrS3, BaHfS3, and SrHfS3, distorted chalcogenide perovskites, with a direct bandgap (1.94–2.41 eV), making them suitable solar cell light absorbers44. Furthermore, Majhi synthesized FeNiSe2 and FeNiSSe as efficient electrocatalysts for water splitting45.

DFT studies have yielded promising chalcogenide perovskite candidates for solar cells. Sun et al.46 identified CaTiS3, BaZrS3, CaZrSe3, and CaHfSe3 as promising candidates for single-junction solar cells. Similarly, Du et al.47,48 proposed Ca3Sn2S3 and ACeTe3 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba) as suitable photovoltaic materials. Likewise, Thakur et al.49 and Liu et al.50 predicted the potential of ABX3 (A = Ba, B = Zr, X = S and/or Se) and ABSe3 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba; B = Hf, Zr) for photovoltaic applications, respectively. Zhang et al.51 further extended this investigation to LaScSe3 for optoelectronic applications. Earlier research has highlighted the potential of chalcogenide perovskites, ABX3 (A = Ca, Sr, or Ba; B = Ti, Zr, or Hf; and X = O, S, or Se) to address the limitations of halide perovskites, particularly regarding concerns about toxicity and stability52.

In this paper, we employ DFT to predict the structural, electronic, and optical properties of chalcogenide perovskites ABSe3 (A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs; and B = Si, Ge, Sn) in triclinic crystallographic phases. The motivation for this study stems from the growing interest in chalcogenide perovskites due to their potential applications in optoelectronics and photovoltaics. Due to the absence of experimental data for comparison with theoretical results on the investigated perovskites, we employed the Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof hybrid functional (HSE06)53. It is a hybrid density functional that combines the strengths of Hartree–Fock theory with DFT. It is particularly designed to address some of the limitations associated with local density approximations (LDA) and generalized gradient approximations (GGA), which often underestimate band gaps in semiconductors and insulators. HSE06 is a powerful tool in computational materials science, providing improved accuracy for electronic structure calculations while also presenting some limitations related to computational cost. HSE06 has been shown to accurately predict bandgaps, electrical, and optical properties for a variety of perovskite materials54.

Computational method

All calculations were carried out with the CASTEP code55 within the Materials Studio 2020 package, employing DFT. CsSnS3 (triclinic, P-1,2) was taken from the material project website (mp-561710)56. Cs atom was systematically replaced with Li, Na, K, and Rb, while Sn atom was substituted with Si and Ge atoms, and the S atoms were replaced with Se atoms. Geometry optimization, electronic, and optical properties, were conducted using HSE06 hybrid functional53. Each exchange–correlation (XC) functional has been calculated using kinetic energy cut-offs of 650 eV with norm-conserving pseudopotential57. The self-consistent field (SCF) tolerance was 1.0 × 10−6 (eV/atom). Furthermore, the total energy tolerance, maximum ionic Hellmann–Feynman force, and maximum ionic displacement tolerance were 1.0 × 10−5 (eV/atom), 0.03 (eV/Å) and 0.001 (Å), respectively. A dense \(12\times 12\times 12\) Monkhorst and Pack mesh grid was used for k-points sampling of the first Brillouin zone. The phonon dispersion curves for the chalcogenide perovskites were calculated using the GGA/PBEsol method58.

The optical properties were calculated using HSE functional by the complex dielectric function \(\varepsilon (\omega )\) given as59,

where \({\varepsilon }_{1}(\omega )\) and \({\varepsilon }_{2}(\omega )\) represents the real and imaginary part of the dielectric constant. The well-known Kramer–Kronig relation connects the real and imaginary sections of the dielectric functions as follows60,61:

where P denotes the principal value of the integral.

Here, u and e represent the polarization of the incident electric field and the electric charge, respectively. Ω denotes the volume of a unit cell. \({\psi }_{k}^{c}\) and \({\psi }_{k}^{\upsilon }\) signify the wave functions of the valence band and conduction band, respectively, at the position k. By using \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{2}(\omega )\), optical properties like reflectivity R(ω), absorption coefficient α(ω), optical conductivity σ(ω), refractive index n(ω), extinction coefficient k(ω) and energy-loss spectrum L(ω) are evaluated as follows62,63,64:

Results and discussion

Structural properties

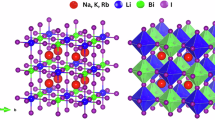

Figure 1 represents the triclinic crystal structure of the chalcogenide perovskite series ABSe3 (A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs; B = Si, Ge, Sn). The A-site cation exhibits a larger ionic radius compared to the B-site cation, consistent with the typical structural features of perovskites. For systematic analysis, the investigated chalcogenide perovskites were categorized into three groups based on the B-site cation: Si-based (ASiSe3), Ge-based (AGeSe3), and Sn-based (ASnSe3).

The substitutions at the A, B and X sites can cause significant improvements in stability and performance65,66. However, by substitutions, the crystal structure of a perovskite material can alter significantly, which can be anticipated using the Goldschmidt tolerance factor (Tf)67. The Tf, Eq. (8), anticipates the viability of a combination of A, B, and X elements to form a perovskite phase by calculating a structural ratio; a value between 0.80 and 1.11 indicates ideal cubic structures or a distorted perovskite structure with tilted octahedral. Structures having Tf values outside the range cannot be considered stable perovskites68,69,70.

RA, RB, and RSe symbolize the Shannon ionic radii of A, B, and Se elements, respectively71. Our investigated perovskites have tolerance factor values ranging from 0.8158 to 1.117 (Table 1), revealing structural stability.

Formation energy (Eform), which represents the energy required to form a material from its constituent elements, was utilized to assess the thermodynamic stability of the perovskites by Eq. (11)72,

The energies of A, B, and Se atoms in their corresponding bulk crystal phases are denoted by EA, EB and ESe, respectively. \({E}_{{ABSe}_{3}}\) is the energy of the ABSe3 unit cell. Materials having low (negative) formation energies are more stable and less prone to break down into their constituent elements. This stability is essential for sustaining the efficiency of perovskite solar cells over time, particularly in conditions of operation73. This stability is critical for assuring the longevity and reliability of perovskite solar cells, which are frequently subjected to changing environmental conditions. The formation energy also influences the development of tandem solar cells, which combine perovskites with silicon or other materials. Perovskite/silicon tandem cells, for example, have achieved efficiencies of more than 31%, demonstrating the potential for optimizing formation energies in multi-junction configurations74. For all studied ABSe3, Eform was calculated to be negative (Table 1), suggesting favorable thermodynamic stability. Interestingly, within each series (Si, Ge, or Sn), the formation energies exhibit a trend of becoming more negative (increasingly stable) as the A-site cation follows (Li < Cs < Rb < K < Na). Within each A-site cation, the formation energy tends to become more negative as the B-site cation changes from Sn to Ge to Si.

Lattice parameters, unit cell volume (V), and theoretical density (D) were calculated and presented in Table 2. The increasing trend in unit cell volume coincides with an increase in lattice parameters, as a result of the increase in the ionic radius of the A-site cation.

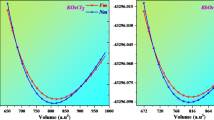

Phonon dispersion

The calculation of phonon dispersion curves provides valuable insights into the dynamical stability of materials by revealing the vibrational frequencies of atoms within the crystal lattice. The phonon dispersion of a material significantly influences its mechanical properties, such as elasticity and hardness, as well as its thermal behavior, including thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity. These factors collectively determine its overall suitability for practical applications, such as structural components and electronic devices75,76. The presence of imaginary frequencies in phonon dispersion curves indicates dynamic instability of the material, whereas their absence signifies stability. Figure 2 depicts the calculated phonon dispersion curves for the chalcogenide perovskites, revealing the absence of imaginary frequencies across all vibrational modes, indicative of their stability77. One remarkable feature from Fig. 2 is the band gap in the phonon spectrum. We can see that this band gap was noticed for NaSiSe3, NaGeSe3, KSiSe3, KGeSe3, RbSiSe3, RbGeSe3, CsSiSe3 and CsGeSe3 meanwhile extremely small for other perovskites. The presence of phonon band gaps, regions in the dispersion where no phonon modes exist, can lead to a reduction in thermal conductivity due to the limited number of available heat-carrying channels77. Therefore, we can conclude that the above-mentioned perovskites have lower thermal conductivity compared to the other compounds.

Electronic properties

Band structures

Figure 3 displays the predicted electronic band structures (BS) for the investigated Si-based, Ge-based, and Sn-based chalcogenide perovskites. The calculated bandgap (Eg) and the difference between indirect and direct gaps (ΔEg) for the investigated perovskites are summarized in Table 3. An indirect bandgap occurs when the maximum energy of the valence band (VB) and the minimum energy of the conduction band (CB) do not align at the same momentum (k-vector). This means that for an electron to transition from the VB to the CB, it must also interact with a phonon (a lattice vibration) to conserve momentum, making the process less efficient. This contrasts with direct bandgap materials, where such transitions can occur without the need for additional momentum exchange, allowing for more efficient photon absorption and emission. For solar cell applications, semiconductors with direct bandgaps are generally considered superior to those with indirect bandgaps. This is because direct bandgap materials exhibit significantly stronger optical absorption at the band edge due to the allowed momentum transitions between electrons and holes. Indirect semiconducting materials can also be efficient for solar cells, particularly when the ΔEg falls within a specific range of approximately 0.2–0.5 eV78. A smaller ΔEg in indirect bandgap semiconductors can potentially decrease electron–hole separation, avoiding fast recombination. According to recent research, the optimal band gap for solar cell applications should fall between 0.9 and 2.5 eV31. The BS reveal that all ABSe3 perovskites exhibit semiconducting behavior with indirect bandgaps. In general, the Eg increases with larger A-cations (Li to Cs) and follows the order Si > Sn > Ge for B-cations. The investigated perovskites exhibit indirect bandgaps within a range of 1.10–2.33 eV. This range indicates the tunability of the bandgap through compositional changes and is comparable to that of other perovskite structures and hybrid organic–inorganic compounds (Table 3). For instance, CH3NH3PbI3 is a widely studied perovskite that has an indirect band gap of approximately 1.6 eV79,80, which is within the range of the ABSe3 perovskites. This material is known for its strong absorption properties and is a leading candidate for solar cell applications. Recent studies have also explored lead-free perovskites, such as (C6H5NH3)BiI4, which have band gaps around 2.14 eV81. These materials are being investigated for their potential in photovoltaic applications while avoiding the toxicity associated with lead. Materials like YMnO3 and its derivatives have been reported to have band gaps around 1.35 eV82, which is close to the lower end of the ABSe3 perovskites’ band gap range. These materials also show promise for solar cell applications due to their suitable band gap energies. Furthermore, the ABSe3 possess a ΔEg range of 0.149–0.493 eV, making them promising candidates for high-efficiency solar cell applications.

Density of states

The density of states (DOS) signifies the number of electronic states possible at each energy level for electrons in a material. The DOS provides a general overview of the electrical structure without specifying which atomic orbitals contribute to various states. In contrast, the partial density of states (PDOS) divides the overall DOS into contributions from individual atomic orbitals or atoms. This allows researchers to investigate how individual atomic qualities affect the material’s electrical properties. The PDOS is derived by projecting the overall density of states onto specific atomic orbitals, such as s, p, or d orbitals, for each atom in the system, as shown in Fig. 4. Analysis of the PDOS of the VB of Li-based and K-based chalcogenides indicates that the states near the Fermi level (0 eV) down to − 10 eV are predominantly composed of Se-p states, with a moderate contribution from B-p states. A smaller contribution is observed from A-p and Se-s states, while A-s and B-s states contribute minimally. For K-based, Rb-based, and Cs-based chalcogenides, the contributions remain predominantly from the transition Se-p electrons, with a small contribution from B-p electrons and a minor contribution of Se-s electrons. The A-cation s states reveal the consistent presence of sharp peaks at around − 55 eV for all compounds in Na-based chalcogenides, − 32 eV for all compounds in K-based chalcogenides, − 27 eV for all compounds in Rb-based chalcogenides, − 21 eV for all compounds in Cs-based chalcogenides. The A-cation p states exhibit sharp peaks around − 25 eV for all compounds in Na-based chalcogenides, − 15 eV for all compounds in K-based chalcogenides, − 12 eV for all compounds in Rb-based chalcogenides, − 8 eV for all compounds in Cs-based chalcogenides. The states at the bottom of the CB are mainly due to the Se-p states. Analysis of the K-based, Rb-based, and Cs-based chalcogenides reveals that the d states of the A-cation exhibit broad peaks within the CB, ranging approximately from 3 to 18 eV.

Optical properties

The optical properties of perovskites play a critical role in understanding their internal structures. The dielectric function, ε(ω), characterizes the interaction of an electromagnetic wave with a material as a function of frequency (ω). It describes how the material polarizes in response to the electric field of the wave. Furthermore, the dielectric function can also provide insights into the interactions between electrons and phonons within the material. The real part of the complex dielectric function, ε₁(ω), reflects the polarization induced in the material by the propagating light wave. While, the imaginary part, ε₂(ω), quantifies the energy absorbed by the material due to the interaction with the electromagnetic wave. Determination of the ε1(ω) and ε2(ω) allows us to calculate other optical properties like absorption, refractive index, dielectric function, conductivity, reflectivity, and energy loss. The ε1(ω) and ε2(ω) parts of dielectric constants are shown in Fig. 5. The ε1(ω) of LiSiSe3, NaSiSe3, KSiSe3, RbSiSe3 and CsSiSe3 at a photon energy of 0.01 are 7.08, 5.91, 5.43, 5.39, and 5.35, respectively (Fig. 5a). The ε1 (ω) at a photon energy of 0.01 for LiGeSe3, NaGeSe3, KGeS3, RbGeSe3 and CsGeSe3 are 8.930, 7.895, 6.085, 5.885, and 5.130, respectively (Fig. 5b). The ε1(ω) values at photon energy of 0.01 for LiSnSe3, NaSnSe3, KSnSe3, RbSnSe3 and CsSnSe3 are 6.789, 6.278, 5.160, 5.009 and 4.946, respectively (Fig. 5c). From the ε1(ω) values of Si-based, Ge-based, and Sn-based chalcogenides, we observe that the maximum ε1(ω) value decreases upon moving cation A from Li to Cs, which could be related to the increasing atomic size and decreasing electronegativity of the alkali metals. Comparing the three groups (Si, Ge, Sn) indicates how replacing Si with Ge or Sn alters the dielectric response. Ge-containing materials generally have higher ε₁(ω) values than their Si and Sn counterparts, indicating a stronger dielectric response, which might be crucial in applications where Ge is preferred for its superior electronic properties. Among the Si-based and Sn-based perovskites, the materials containing Li and Na exhibit higher values of the ε₁(ω). Materials with high ε₁(ω) at low energies are often more suitable for applications in optoelectronic devices, where a high dielectric constant is desirable for efficient charge separation and transport. LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3 exhibit the highest ε1(ω) values at lower energies ~ (0.01 to 5.0) eV. Therefore, LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3 exhibit competitive ε1(ω) values compared to traditional (~ 11.7 for silicon85, 9.5 for CdTe86) and emerging materials (~ 6.5 for CH3NH3PbI387), suggesting their potential for effective use in solar cells, albeit with considerations for stability, cost, and scalability. For most Si-based, Ge-based, and Sn-based chalcogenides, ε1(ω) remains positive up to approximately 7.48–7.91 eV, 6.43–7.81 eV, and 7.15–7.95 eV, respectively. The ability to maintain positive ε₁(ω) at high energies means these materials are less likely to exhibit significant optical absorption losses in the visible and near-UV regions, which can enhance their performance in optoelectronic devices. The ε2(ω) starts increasing from zero at around 1.8 eV, which is an absorption edge and reaches its maximum value around 7.8 eV, which reveals that the absorption is maximum in the ultra-violet region.

The refractive index n(ω) indicates the amount of light refracted or bent, when entering a material. Figure 6a–c represents the refractive index (real part) for (a) Si-based (b), Ge-based, and (c) Sn-based chalcogenides. Figure 6a depicts that LiSiSe3, NaSiSe3, KSiSe3, RbSiSe3 and CsSiSe3 have n(ω) of ∼ 2.661, 2.432, 2.330, 2.323, and 2.318 at photon energy of 0.01, respectively. From Fig. 6b, the n(ω) for LiGeSe3, NaGeSe3, KGeS3, RbGeSe3 and CsGeSe3 are 2.989, 2.809, 2.466, 2.425 and 2.475, respectively. The n(ω) values for LiSnSe3, NaSnSe3, KSnSe3, RbSnSe3, and CsSnSe3 are 2.605, 2.505, 2.271, 2.238 and 2.224, respectively (Fig. 6c). For each group (Si, Ge, Sn), the refractive index generally decreases as the cation size increases from Li to Cs. This trend suggests that larger cations lead to a lower refractive index, likely due to changes in lattice parameters and bonding characteristics. The Ge-based chalcogenides exhibit the highest refractive indices compared to Si and Sn-based materials. A higher refractive index can improve light trapping within the solar cell by increasing the likelihood of light being reflected and scattered within the active layer. This can enhance the absorption of light, especially in thin-film solar cells where the thickness of the absorbing material is limited. Given that LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3 have the highest refractive indices among the materials listed, with values of 2.989 and 2.809 respectively. They are comparable to Si (~ 3.5)88 or slightly higher than CdTe (~ 2.6)89 and perovskites (CH3NH3PbI3, ~ 2.5–3.0)90. This suggests they are competitive with these well-known materials in terms of light interaction, which is significant for solar cell and optoelectronic applications. Figure 7a–c represents the extinction coefficient, k(ω), the imaginary part of the complex refractive index, for (a) Si-based, (b) Ge-based, and (c) Sn-based chalcogenides. It represents the attenuation or absorption of light as it propagates through a material. The local maxima peak of the k(ω) for our study perovskites centered around 8.0 eV. It is noted that Si-based chalcogenides exhibit the highest k(ω) compared with Ge-based and Si-based ones. Generally, the Li and Na-based chalcogenides tend to display higher values of the n(ω) and k(ω) compared to other materials in the same category.

Figure 8 shows the absorption coefficient \(\alpha \left(\varepsilon \right)\) of chalcogenide perovskites. Within the 2–15 eV energy region, the absorption coefficient progressively decreases as the A-cation changes from Li to Cs. In the higher energy region (15 eV to 45 eV), the absorption coefficient slightly increases as the A-cation moves from K to Cs. Across the 2–45 eV energy range, the absorption coefficient generally decreases as the B-cation changes from Si to Sn. Notably, all the studied chalcogenide perovskites exhibit strong absorption in the UV region.

The complex conductivity, σ(ω), describes the conduction of electrons due to an applied electromagnetic field. It is a complex function consisting of both real, σ1(ω), and imaginary component, σ2(ω). The σ1(ω) indicates how effectively a material can conduct electricity when subjected to electromagnetic radiation. Figure 9a–c illustrates the computed σ1(ω) spectra for studied perovskites at incoming photon energy ranging from 0 to 50 eV. All ABSe3 materials have a maximum σ1(ω) within the range of ~ 1–15 eV of photon energy, which is promising for their application in UV optical systems. This concurrence suggests that light absorption leads to the generation of free carriers, which in turn contribute to electrical conductivity. In this energy range, the σ1(ω) primarily corresponds to transitions involving Se-p electron with a moderate contribution of B-p, small of A-p, Se-s, and a minor contribution of A-s and B-s electrons for Li-based and Na-based chalcogenides. For K-based, Rb-based, and Cs-based chalcogenides, the contributions to the σ1(ω) remain predominantly from the transition Se-p electrons, with a small contribution from B-p electrons and a minor contribution of Se-s electrons. High σ1(ω) peaks were observed at ~ 16, 20, and 25 eV mainly corresponding to transitions concerning Se-p electron Ce-p, Rb-p, and K-p, respectively. Consistent with the absorption trends, the magnitude of the σ1(ω) spectra is higher for Si-based chalcogenide perovskites compared to Ge-based and Sn-based perovskites. The σ2(ω) represents the reactive component of the conductivity, which to the storage of energy in the material. The σ2(ω) curves extend from 0 eV incident photon energy up to 50 eV. At around 0 eV to 7 eV input photon energy, ABSe3 reach negative maximum values of about (− 3.14, − 3.489, − 3.480, − 3.619 and − 3.651) 1/fs for LiSiSe3, NaSiSe3, KSiSe3, RbSiSe3 and CsSiSe3 respectively (Fig. 9d). Negative maximum σ2(ω) values for LiGeSe3, NaGeSe3, KGeSe3, RbGeSe3, and CsGeSe3 were obtained at around − 2.733, − 2.947, − 3.00, − 3.074, and − 3.407 1/fs, respectively (Fig. 9e). Figure 9f reveals that for LiSnSe3, NaSnSe3, KSnSe3, RbSnSe3 and CsSnSe3 negative maximum σ2(ω) values at around − 3.170, − 3.045, − 2.741, − 2.996 and − 3.249 respectively. The negative maximum values of σ2(ω) in chalcogenide perovskites significantly impact their overall conductivity by reducing it and indicating a capacity for energy storage. The larger negative values in chalcogenide perovskites indicate that these materials may be more effective for applications requiring efficient energy storage and conversion, such as in solar cells. At around 7 eV to 15 eV input photon energy, Si-based, Ge-based, and Sn-based perovskites maximum positive of σ2 (ω) about range (2–4), (2.1–3.5) and (1.85–3.2) 1/fs. The shift to positive σ2(ω) values implies that charge carriers (electrons) are becoming more mobile and contributing to the conduction process.

The reflectivity, R(ω), mainly measures the ability of a material to reflect incident light. Figure 10a–c depicts the R(ω) values for ABSe3 at a photon energy of 0.01 eV. The R (ω) values for LiSiSe3, NaSiSe3, KSiSe3, RbSiSe3, and CsSiSe3 are ~ 0.205, 0.174, 0.159, 0.158, and 0.157, respectively (Fig. 10a). Similarly, for LiGeSe3, NaGeSe3, KGeSe3, RbGeSe3, and CsGeSe3, the R(ω) values are 0.248, 0.225, 0.179, 0.173, and 0.180, respectively (Fig. 10b). Finally, Fig. 10c shows that the R(ω) values for LiSnSe3, NaSnSe3, KSnSe3, RbSnSe3, and CsSnSe3 are 0.198, 0.184, 0.151, 0.146, and 0.144, respectively. For efficient solar cells, lower reflectivity is desirable because it means that more incident light is absorbed rather than reflected. Across all groups (Si-based, Ge-based, and Sn-based), the reflectivity R(ω) generally tends to decrease as we move from Li-based to Cs-based chalcogenides. This trend suggests that as the atomic number of the A cation increases, the material becomes slightly more transparent or less reflective at the given photon energy (0.01 eV). Among the different groups, Ge-based chalcogenides generally exhibit higher reflectivity values than Si-based and Sn-based chalcogenides, at 0.01 eV. This implies that Ge-based chalcogenides may reflect more light, which could reduce their effectiveness in absorbing photons and thus converting them into electrical energy in solar cell applications. Materials like CsSnSe3, which have the lowest reflectivity (~ 0.144), are therefore more favorable for solar cell applications as they would absorb lighter and potentially generate more electricity. While the Ge-based ABSe3 chalcogenides show slightly higher reflectivity, they still fall within a reasonable range that could be optimized through material engineering (e.g., surface texturing, anti-reflective coatings) for better solar cell performance. The reflectivity of the ABSe3 materials, particularly the Sn-based compounds, is comparable to or lower than that of some well-known materials used in thin-film solar cells, such as Cu₂ZnSnS₄ (20–25% in the visible spectrum)91, SrTiO3 (R around 20–30% in the visible spectrum)92, and CH3NH3PbI3 (5–15% in the visible spectrum)93. This low reflectivity makes ABSe3 materials potential candidates for solar applications. The reflectivity is more significant in the range of 1.2 eV to 35 eV and becomes negligible at above 45 eV.

The electron loss energy, L(ω), partly describes the energy loss due to fast-moving electrons through the lattice. Figure 11 reveals that for the perovskite materials, L(ω) is zero for photon energies between 0 and 4.48 eV. In Fig. 11a, a sharp peak is found at 19.5, 18.9, 16.7, 23.9 and 21.5 eV for LiSiSe3, NaSiSe3, KSiSe3, RbSiSe3 and CsSiSe3, respectively. Figure 11b also exhibits sharp peaks in the L(ω) spectra for Ge-based perovskites. The peak positions show variations across the A-cation (Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs), with values of 19.4, 18.6, 16.8, 22.8, and 21.4 eV, respectively. Similarly, the specific peak positions for LiSnS3, NaSnS3, KSnS3, RbSnS3, and CsSnS3 are 18.9, 18.7 eV, 16.4 eV, 22.8 eV, and 20. 8 eV, respectively (Fig. 11c). The LiSiS3, LiGeS3 and LiSnS3 perovskites show highest L(ω) values, while KSiS3, KGeS3, and RbSnS3 show lowest peaks compared to the others perovskites.

Conclusions

This study employs density functional theory calculations to comprehensively investigate the structural, electronic, and optical properties of triclinic chalcogenide perovskites, ABSe3 (A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs; B = Si, Ge, Sn). Our findings reveal several important insights: Firstly, the tolerance factor and negative formation energy values suggest that these compounds exhibit both thermodynamic and structural stability, indicating their potential for practical applications. Secondly, the absence of imaginary phonon modes in the phonon dispersion curves confirms the dynamical stability of ABSe3 perovskites, eliminating concerns about structural instability in practical applications. Thirdly, examination of the band structures indicates all studied perovskites exhibit favorable indirect band gaps (1.10–2.33 eV) with a small difference from direct gaps (0.149–0.493 eV), providing potential applications, particularly in photovoltaics. A larger A-cation (Li to Cs) generally leads to a wider band gap, while for B-cations, Eg follows the order Si > Sn > Ge. Finally, the predicted optical properties of the proposed chalcogenide perovskites are comparable to some of the traditional and emerging materials. LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3 exhibit the highest ε1(ω) values at lower energies ~ (0.01 to 5.0) eV. Therefore, LiGeSe3 and NaGeSe3 exhibit competitive ε1(ω) values compared to traditional (Si, CdTe) and emerging materials (e.g., CH3NH3PbI3). They also have the highest n(ω) among the ABSe3 materials listed, with close to Si and slightly higher than CdTe and CH3NH3PbI3. The ABSe3 materials exhibit a high absorption coefficient within the energy range of ~ 2–15 eV, and their reflectivity, particularly the Sn-based compounds (e.g., CsSnSe3), are comparable to or lower than that of some well-known materials used in thin-film solar cells, such as Cu₂ZnSnS₄, SrTiO3, and CH3NH3PbI3. The properties suggest ABSe3 could be promising candidate materials for solar cell applications. Future research should focus on experimentally validating the predicted properties of ABSe3 perovskites through synthesis, characterization, and optical/electronic measurements. Exploring other compositions, such as doping and mixed systems, could further optimize their properties. Additionally, simulating and developing prototypes for photovoltaic devices will help assess the real-world efficiency of these materials. Finally, studying their environmental stability and toxicity is crucial for ensuring safe and practical applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Jana, M. K. et al. Direct-bandgap 2D silver–bismuth iodide double perovskite: The structure-directing influence of an oligothiophene spacer cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141(19), 7955–7964 (2019).

Yang, J., Zhang, P. & Wei, S. H. Band structure engineering of Cs2AgBiBr 6 perovskite through order–disordered transition: A first-principle study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9(1), 31–35 (2018).

Xiao, Z. et al. Intrinsic instability of Cs2In (I) M (III) X6 (M = Bi, Sb; X = halogen) double perovskites: A combined density functional theory and experimental study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139(17), 6054–6057 (2017).

Bhamu, K. C., Soni, A. & Sahariya, J. Revealing optoelectronic and transport properties of potential perovskites Cs2PdX6 (X = Cl, Br): A probe from density functional theory (DFT). Sol. Energy 162, 336–343 (2018).

Zhou, L., Xu, Y. F., Chen, B. X., Kuang, D. B. & Su, C. Y. Synthesis and photocatalytic application of stable lead-free Cs2AgBiBr 6 perovskite nanocrystals. Small 14(11), 1703762 (2018).

Reshak, A. H. Ab initio study of TaON, an active photocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16(22), 10558–10565 (2014).

Arockiya Dass, K. T., Hossain, M. K. & Marasamy, L. Highly efficient emerging Ag2BaTiSe4 solar cells using a new class of alkaline earth metal-based chalcogenide buffers alternative to CdS. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1473 (2024).

Liang, Y. et al. Tapping the light emitting potential of chalcogenide perovskite SrHfS3 via Eu2+ doping. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12(6), 2301977 (2024).

Tiwari, D., Hutter, O. S. & Longo, G. Chalcogenide perovskites for photovoltaics: Current status and prospects. J. Phys. Energy 3(3), 034010 (2021).

Sopiha, K. V., Comparotto, C., Márquez, J. A. & Scragg, J. J. Chalcogenide perovskites: Tantalizing prospects, challenging materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10(3), 2101704 (2022).

Hossain, M. K. et al. An extensive study on multiple ETL and HTL layers to design and simulation of high-performance lead-free CsSnCl3-based perovskite solar cells. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2521 (2023).

Yuan, M. et al. Controlling the band gap to improve open-circuit voltage in metal chalcogenide based perovskite solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 215, 374–379 (2016).

Rani, U. et al. Electronic structure, theoretical power conversion efficiency, and thermoelectric properties of bismuth-based alkaline earth antiperovskites. J. Mol. Model. 29(10), 329 (2023).

Leng, K., Xia, W. & Zhu, X. Advanced nanostructured perovskite oxides: Synthesis, physical properties, structural characterizations and functional applications. Adv. Ceram. Energy Environ. Appl. 1, 13–81 (2021).

Ye, X. et al. Emergent physical properties of perovskite-type oxides prepared under high pressure. Dalton Trans. 51(5), 1745–1753 (2022).

Pradhan, P. K., Mohanty, N. K., Mishra, G. K. & Behera, B. Concepts and recent advancements in perovskite metal oxides. In Perovskite Metal Oxides (eds Pradhan, P. K. et al.) 3–22 (Elsevier, 2023).

Rani, M. et al. Rare earth-based oxides double perovskites A2NiMnO6 (A= La and Gd): Applications in magneto-caloric, photo-catalytic and thermoelectric devices. Physica B 680, 415645 (2024).

Bairwa, J. K. et al. Modeling and simulation of multifaceted properties of X2NaIO6 (X = Ca and Sr) double perovskite oxides for advanced technological applications. J. Mol. Model. 29(12), 379 (2023).

Rani, M. et al. Ab-initio calculations of structural, optoelectronic, thermoelectric, and thermodynamic properties of mixed-halide perovskites RbPbBr 3−xIx (x = 0 to 3): Applicable in renewable energy devices. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 12(8), 083006 (2023).

Kumari, S. et al. Computational investigation of the fundamental physical properties of lead-free halide double perovskite Rb2NaCoX6 (X = Cl, Br, and I) materials: Potential prospects for sustainable energy. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 1, 2450323 (2024).

Ravi, V. K. et al. Colloidal BaZrS3 chalcogenide perovskite nanocrystals for thin film device fabrication. Nanoscale 13(3), 1616–1623 (2021).

Amrillah, T. et al. Environment-friendly copper-based chalcogenide thin film solar cells: Status and perspectives. Mater. Horiz. 10(2), 313–339 (2023).

Altaf, A. et al. Metal/covalent organic framework encapsulated lead-free halide perovskite hybrid nanocatalysts: Multifunctional applications, design, recent trends, challenges, and prospects. ACS Omega 1, 1 (2024).

Kumar, M. et al. Advances in green energy conversion efficiency and interfacial engineering investigations of lead-free FASnI3-based PSC device. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 193, 112139 (2024).

Podapangi, S. K. et al. Green solvents, materials, and lead-free semiconductors for sustainable fabrication of perovskite solar cells. RSC Adv. 13(27), 18165–18206 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. SCAPS simulation and DFT study of lead-free perovskite solar cells based on CsGeI3. Mater. Chem. Phys. 306, 128084 (2023).

Dubey, A. et al. Lead-free alternative cation (Ethylammonium) in organometallic perovskites for thermoelectric applications. J. Mol. Model. 30(3), 77 (2024).

Okumura, R., Oku, T. & Suzuki, A. Electronic structures and properties of lead-free cesium-or rubidium-based perovskite halide compounds by first-principles calculations. Nano Trends 4, 100020 (2023).

Sarker, M. A., Muntasir, M., Momin, M. A., Solayman, M. & Islam, M. R. Pressure-induced structural, electronic, and optical properties of lead-free NaGeX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, and I) perovskites: First-principles calculation. Adv. Theory Simulat. 7(7), 2400112 (2024).

Chauhan, A. & Oudhia, A. First-principle density functional theory-derived nonleaded KSn1−xGexI3-based perovskite solar cells: A theoretical study. Energy Technol. 12(2), 2300772 (2024).

Ju, M. G., Dai, J., Ma, L. & Zeng, X. C. Perovskite chalcogenides with optimal bandgap and desired optical absorption for photovoltaic devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 7(18), 1700216 (2017).

Tong, J. et al. Wide-bandgap metal halide perovskites for tandem solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 6(1), 232–248 (2020).

Swarnkar, A. et al. Are chalcogenide perovskites an emerging class of semiconductors for optoelectronic properties and solar cell? Chem. Mater. 31(3), 565–575 (2019).

Basera, P. & Bhattacharya, S. Chalcogenide perovskites (ABS3; A = Ba, Ca, Sr; B= Hf, Sn): An emerging class of semiconductors for optoelectronics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13(28), 6439–6446 (2022).

Agiorgousis, M. L., Sun, Y. Y., Choe, D. H., West, D. & Zhang, S. Machine learning augmented discovery of chalcogenide double perovskites for photovoltaics. Adv. Theory Simul. 3(1), 1900200 (2020).

Majhi, K. C. & Yadav, M. Transition metal-based chalcogenides as electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. ACS Eng. Au 3(5), 278–284 (2023).

Cen, Y. L. et al. Design of lead-free and stable two-dimensional Dion–Jacobson-type chalcogenide perovskite A′ La2B3S10 (A′ = Ba/Sr/Ca; B= Hf/Zr) with optimal band gap, strong optical absorption, and high efficiency for photovoltaics. Chem. Mater. 32(6), 2450–2460 (2020).

Mustafa, G. M. et al. First-principles calculations to investigate HgY2S/Se4 spinel chalcogenides for optoelectronic and thermoelectric applications. J. Market. Res. 22, 97–106 (2023).

Perera, S. et al. Chalcogenide perovskites—An emerging class of ionic semiconductors. Nano Energy 22, 129–135 (2016).

Shaili, H. et al. Synthesis of the Sn-based CaSnS3 chalcogenide perovskite thin film as a highly stable photoabsorber for optoelectronic applications. J. Alloys Compd. 851, 156790 (2021).

Pandit, N. et al. Physical properties and power conversion efficiency of SrZrX3 (X = S and Se) chalcogenide perovskite solar cell. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 1, 2450345 (2024).

Pandit, N. et al. Effect of anion (S−2 & Se−2) replacement on photovoltaic properties in transition metal (Ba-Barium) chalcogenide perovskites. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 1, 2550059 (2024).

Nishigaki, Y. et al. Extraordinary strong band-edge absorption in distorted chalcogenide perovskites. Solar Rrl 4(5), 1900555 (2020).

Majhi, K. C. & Yadav, M. Bimetallic chalcogenide nanocrystallites as efficient electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. J. Alloys Compds. 852, 156736 (2021).

Sun, Y. Y., Agiorgousis, M. L., Zhang, P. & Zhang, S. Chalcogenide perovskites for photovoltaics. Nano Lett. 15(1), 581–585 (2015).

Du, J. & Shi, J. J. 2D Ca3Sn2S7 chalcogenide perovskite: A graphene-like semiconductor with direct bandgap 0.5 eV and ultrahigh carrier mobility 6.7 × 104 cm2 V−1 s−1. Adv. Mater. 31(51), 1905643 (2019).

Du, J. et al. Cerium-based lead-free chalcogenide perovskites for photovoltaics. Phys. Rev. B 104(23), 235206 (2021).

Thakur, N., Kumar, P., Neffati, R. & Sharma, P. Design and simulation of chalcogenide perovskite BaZr (S, Se) 3 compositions for photovoltaic applications. Phys. Scr. 98(6), 065921 (2023).

Liu, D., Peng, H., He, J. & Sa, R. Alloy engineering to tune the optoelectronic properties and photovoltaic performance for Hf-based chalcogenide perovskites. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 169, 107919 (2024).

Liu, D., Zeng, H., Peng, H. & Sa, R. Computational study of the fundamental properties of Zr-based chalcogenide perovskites for optoelectronics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25(19), 13755–13765 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Prediction and synthesis of a selenide perovskite for optoelectronics. Chem. Mater. 35(11), 4128–4135 (2023).

Peng, Y., Sun, Q., Chen, H. & Yin, W. J. Disparity of the nature of the band gap between halide and chalcogenide single perovskites for solar cell absorbers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10(16), 4566–4570 (2019).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118(18), 8207–8215 (2003).

Shakil, M. et al. Theoretical investigation of structural and mechanical stability, electronic, optical, and transport behaviour of double halide perovskites K2GaBiX6 (X = Cl, Br, and I) for optoelectronic applications. Comput. Condens. Matter 1, e00941 (2024).

Cheng, J. et al. From VIB-to VB-Group transition metal disulfides: Structure engineering modulation for superior electromagnetic wave absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 16(1), 29 (2024).

The Materials Project. https://materialsproject.org/.

Shirley, E. L., Allan, D. C., Martin, R. M. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Extended norm-conserving pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 40(6), 3652 (1989).

Smrčok, Ľ, Mach, P. & Le, A. Bail b. Department of Theoretical Chemistry, Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, SK-845 36. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 14, 357–361 (1981).

Ur Rehman, S. et al. Pressure induced structural and optical properties of cubic phase SnSe: An investigation for the infrared/mid-infrared optoelectronic devices. J. Alloys Compds. 695, 194–201 (2017).

Wooten, F. Optical Properties of Solids (Academic Press, 1972).

Segall, M. D. et al. First-principles simulation: Ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14(11), 2717 (2002).

Jana, D., Sun, C. L., Chen, L. C. & Chen, K. H. Effect of chemical doping of boron and nitrogen on the electronic, optical, and electrochemical properties of carbon nanotubes. Prog. Mater. Sci. 58(5), 565–635 (2013).

Saha, S., Sinha, T. P. & Mookerjee, A. Electronic structure, chemical bonding, and optical properties of paraelectric BaTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 62(13), 8828 (2000).

Yang, M. et al. Comparison of optical properties between Wurtzite and zinc-blende Ga0.75Al0.25N. Optik 125(1), 424–427 (2014).

Saliba, M. et al. Incorporation of rubidium cations into perovskite solar cells improves photovoltaic performance. Science 354(6309), 206–209 (2016).

Saliba, M. et al. Cesium-containing triple cation perovskite solar cells: Improved stability, reproducibility and high efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 9(6), 1989–1997 (2016).

Gautam, S. & Gupta, D. C. Exploring the structural, mechanical, magneto-electronic and thermophysical properties of f electron based XNpO3 perovskites (X = Na, Cs, Ca, Ra). Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8918 (2024).

Randall, C. A., Bhalla, A. S., Shrout, T. R. & Cross, L. E. Classification and consequences of complex lead perovskite ferroelectrics with regard to B-site cation order. J. Mater. Res. 5(4), 829–834 (1990).

Han, G. et al. Additive selection strategy for high performance perovskite photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. C 122(25), 13884–13893 (2018).

Aleksandrov, K. S. The sequences of structural phase transitions in perovskites. Ferroelectrics 14(1), 801–805 (1976).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Cryst. Phys. Diffract. Theor. Gen. Crystallogr. 32(5), 751–767 (1976).

Xu, N. et al. First-principles investigations for the hydrogen storage properties of XVH3 (X¼Na, K, Rb, Cs) perovskite type hydrides. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2(6), 4825 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Scalable fabrication of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3(4), 1–20 (2018).

Aranda, C. et al. Formation criteria of high efficiency perovskite solar cells under ambient conditions. Sustain. Energy Fuels 1(3), 540–547 (2017).

Lu, Y. et al. Theoretical prediction on the stability, elastic, electronic and optical properties of MAB-phase M4 AlB4 compounds (M= Cr, Mo, W). RSC Adv. 14(2), 1186–1194 (2024).

Ono, S. & Kobayashi, D. Role of the M point phonons for the dynamical stability of B2 compounds. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7258 (2022).

Allal, A., Halit, M., Saib, S., Luo, W. & Ahuja, R. Phase stability, phonon, electronic, and optical properties of not-yet-synthesized CsScS2, CsYS2, and APmS2 (A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs) materials: Insights from first-principles calculations. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 150, 106936 (2022).

Sun, Q., Chen, H. & Yin, W. J. Do chalcogenide double perovskites work as solar cell absorbers: a first-principles study. Chem. Mater. 31(1), 244–250 (2018).

Quarti, C. et al. Structural and optical properties of methylammonium lead iodide across the tetragonal to cubic phase transition: Implications for perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 9(1), 155–163 (2016).

Challinger, S. E., Baikie, I. D., Harwell, J. R., Turnbull, G. A. & Samuel, I. D. An investigation of the energy levels within a common perovskite solar cell device and a comparison of DC/AC surface photovoltage spectroscopy Kelvin probe measurements of different MAPBI3 perovskite solar cell device structures. MRS Adv. 2(21–22), 1195–1201 (2017).

Li, X. L. et al. (C6 H5 NH3) BiI4: A lead-free perovskite with > 330 days humidity stability for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 7(26), 15722–15730 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Lead-free perovskite narrow-bandgap oxide semiconductors of rare-earth manganates. ACS Omega 5(15), 8766–8776 (2020).

Sujith, C. P., Joseph, S., Mathew, T. & Mathew, V. First-principles investigation of structural, electronic and optical properties of quasi-one-dimensional barium cadmium chalcogenides Ba2CdX3 (X = S, Se, Te) using HSE06 and GGA-PBE functionals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 161, 110488 (2022).

Tang, T. & Tang, Y. Promising anti-perovskites Ba6CCh4 (Ch = S, Se, Te) with direct bandgaps and great light absorption: A first-principles study. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 157, 111337 (2023).

Sze, S. M. & Ng, K. K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices 3rd edn. (Wiley, 2007).

Adachi, S. Properties of Semiconductor Alloys: Group-IV, III-V and II-VI Semiconductors (Wiley, 2005).

Umari, P., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Relativistic GW calculations on CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 perovskites for solar cell applications. Sci. Rep. 4(1), 4467 (2014).

Edwards, D. F. & Ochoa, E. Infrared refractive index of silicon. Appl. Opt. 19(24), 4130–4131 (1980).

Davis, P. W. & Shilliday, T. S. Some optical properties of cadmium telluride. Phys. Rev. 118(4), 1020 (1960).

Shukla, A., Sharma, V. K., Gupta, S. K. & Verma, A. S. Investigations of fundamental physical and thermoelectric properties of methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) perovskites. Mater. Res. Express 6(12), 126323 (2020).

Katagiri, H., Ishigaki, N., Ishida, T. & Saito, K. Characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films prepared by vapor phase sulfurization. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 40(2R), 500 (2001).

Cardona, M. Optical properties and band structure of SrTiO3 and BaTiO3. Phys. Rev. 140(2A), A651 (1965).

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(17), 6050–6051 (2009).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.Kh.M.: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing-original draft. M.T.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. S. I. E.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. A.A.F.: Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmoud, E.K., El-dek, S.I., Farghali, A.A. et al. Investigating the potential of triclinic ABSe3 (A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs; B = Si, Ge, Sn) perovskites as a new class of lead-free photovoltaic materials. Sci Rep 14, 22691 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72555-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72555-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling the Electronic, Optical, and Mechanical Properties of Lithium-Based Perovskites for Next-Generation Solar Cells

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)

-

Strain Engineering for Enhanced Photovoltaic Performance of Lead-Free Cs2AgBiI6 Double Perovskite: Insights from Density Functional Theory

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)