Abstract

The removal of pollutants from the environment has become a global demand. The current study aimed to relieve the Ni toxicity effect on the germination, growth, and grain yield of maize by using Azolla pinnata as a phytoremediator. Azolla-treated and untreated nickel solutions [0 (control), 24, 70, 140 and 190 ppm] were applied for germination and pot experiments. Electron microscope examination cleared the Ni accumulation in Azolla’s cell vacuole and its adsorption on the cell wall. The inhibition of the hydrolytic enzyme activity reduces maize germination; maximal inhibition was 57.1% at 190 ppm of Ni compared to the control (100%). During vegetative growth, Ni stimulated the generation of H2O2 (0.387 mM g−1 F Wt at 190 ppm of Ni), which induced maximal lipid peroxidation (3.913 µMDA g−1 F Wt) and ion leakage (74.456%) compared to control. Chlorophyll content and carbon fixation also showed significant reductions at all Ni concentrations; at 190 ppm, they showed maximum reductions of 56.2 and 63%, respectively. However, detoxification enzymes’ activity such as catalase and antioxidant substances (phenolics) increased. The highest concentration of Ni (190 ppm) had the most effect on constraining yield, reaching zero for the weight of 100 grains at 190 ppm of Ni. Azolla-treated Ni solutions amended all determinant parameters, indicating a high percentage of changes in hydrolytic enzyme activity (125.2%) during germination, chlorophyll content (77.6%) and photosynthetic rate (120.1%). Growth measurements, carbon fixation, and yield components showed a positive association. Thus, we recommended using Azolla as a cost-effective and eco-friendly strategy to recover Ni-polluted water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy metal build-up in soil has grown significantly because of natural processes as well as human (industrial) activity1. The presence of various pollutants such as organic or and inorganic elements in landfills have a global interest. Such toxins and heavy metalloids can represent a main danger to human health as well as eco-toxic effects on different ecosystems (terrestrial and aquatic)2. Heavy metals, such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and nickel (Ni), are prevalent contaminants in the soil environment. This form of pollution is physiologically hazardous, widespread, and long-lasting in the soil environment3.

Nickel is considered an essential element for the growth of plants, and its deficiency has been observed in some perennial species4. Primary resources of Ni may be natural processes such as erosion of rock, weathering, and volcanic explosion) or human-causes such as industrial discharges, mine actions, electroplating and municipal sewage sludge that caused contamination in ecosystems5,6,7. Increasing Ni levels above the permitted levels in water (0.02 mg l−1) and soil (35 mg kg−1) causes harmfulness to all living organisms8,9.

Nickel is a necessary micronutrient in plants because it is a component of the active site of the urease enzyme which hydrolyzes urea in plant tissues10. Excess concentrations of Ni in plants cause chlorosis and necrosis, as with other heavy metals, disrupt Fe uptake and metabolism11. Nickel’s toxic effects on plants include changes in the germination process, total dry matter production and yield, all of which have a negative impact on the plant. The activity of hydrolytic enzymes was enhanced at lower Ni concentrations and decreased at higher ones12. Lethal levels of Ni damage plants by disturbing a range of physiological functions (including enzyme activity), root progress, photosynthesis, and element uptake13.

Nickel has a substantial impact on plant metabolic processes because of its capacity to form reactive oxygen species that can induce oxidative stress14. When heavy metals are present in plants, they quickly assemble into reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in oxidative stress15. Plants are bestowed with a variety of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants that aggravate their ability to scavenge excess ROS and, in that way, play a critical role in ROS homeostasis. Antioxidant enzymes in plants include superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX)16.

Moreover, Ni toxicity affects photosynthesis and gas exchange processes in many ways, resulting in an overall inhibition of photosynthesis12. The drop in chlorophyll concentration caused by the Ni treatment may have reduced the chloroplast’s capacity to absorb light, indirectly impairing photosynthesis. Chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics are a good measure of the level of abiotic stress, and photosystem II (PS II) is particularly susceptible to damage from metal stress17. Li et al.18 recently demonstrated that Elsholtzia argyi’s decreased capacity for photosynthesis under heavy metal stress is correlated with decreased photochemical efficiency (PS), photochemical quenching (qP), electron transport rate (ETR), and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ).

Metal contamination of soil is an environmental risk and chemical treatments for heavy metal decontamination are generally very expensive and not applicable to agricultural lands. Therefore, many strategies are used to restore contaminated areas. Phytoremediation is a promising method based on the use of hyper-accumulator plant species that can tolerate toxic heavy metals in the environment19. Aquatic phytoremediation removes contaminants from water and restores damaged water bodies. Aquatic phytoremediation takes place by macrophytes (freshwater-adapted angiosperms, pteridophytes, and ferns) to remove and reduce pollutants in aquatic bodies20. Those macrophytes are able to accumulate or breakdown pollutants by rhizo/phyto-filtration, phyto-extraction, phyto-volatilization, and phyto-degradation.

Maize is one of the world’s most popular, oldest, and most potent cereal crops, used for food, fodder, and even medicine. More than 3500 applications for corn products have been proposed. Because of its nutritional value, it addresses health-related concerns. Maize is also high in vitamins A, B, and E, as well as a variety of minerals. It has decreased hypertension and helped to avoid neural-tube abnormalities in children. According to Lasat21 metal hyperaccumulators as maize offer several benefits, but they may be sluggish to develop and generate little biomass, making cleanup of polluted locations time-consuming. To overcome these obstacles, some scientists proposed the utilization of metal chelators to improve chemical phytoextraction. The strategy utilizes high-biomass crops that are chemically treated with chelating organic acids to boost their mobility in soil, causing them to absorb significant quantities of metals22. Azolla can be used as a natural low-cost effective chelator to extract metals from soil, reducing their availability in soil let maize uptake less metal.

The responses of maize when it faces more than one stress (double or triple) has been received more interest, such as drought plus heat or heavy metal exposure. To meet these issues in maize, transgenic approaches have already caused the production of viable stress resistant variants; natural variation and genetic engineering are used23. On the one hand, quantitative trait loci (QTL) linked with multiple-stress tolerance are being used via molecular breeding and genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which might be used in future breeding efforts for more robust maize varieties23.

The aim of this study was to use Azolla pinnata as an eco-friendly remediator to improve maize plant growth under Ni-induced stress. Azolla pinnata was used to relieve the inhibitory effects of Ni-polluted solutions on maize germination, vegetative growth, photosynthetic capacity and grain yield. It is inventive to use Azolla in Ni-contaminated soil that is cultivated with maize.

Materials and methods

Materials

Seeds of Zea mays were kindly obtained from Legumes Crops Department; Field Crops Research Institute; Agricultural Research Centre, Giza, Egypt. Azolla Pinnata was obtained from Water and Land Department; Field Crops Research Institute; Agricultural Research Centre, Giza, Egypt.

Preparation of Azolla-treated Ni solutions

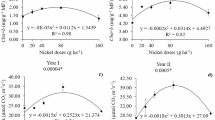

To assess the toxicity of nickel chloride (NiCl2) on the germination of maize seeds, various concentrations of NiCl2 (0, 100, 300, 500, 1000 and 2000 ppm) were used (preliminary experiment). The lethal concentration was 2000 ppm NiCl2. Five conical flasks (250 ml capacity) with different Ni solutions and water (0, 100, 300, 500 and 1000 ppm) were inoculated with 10 g of fresh Azolla (10%, wt/v). After four days of incubation, Ni solutions were filtered through filter paper and the concentration of Ni ions for each original and Azolla-treated Ni solutions was determined by using a Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (MPAES, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA 95051, United States). The concentrations of Ni ions were represented in Fig. 1 before and after Azolla treatment.

Laboratory experiment (germination stage)

Maize seeds were sterilized in 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution (3 min). Then, seeds washed with distilled water. In petri dishes, seven seeds were distributed on filter paper. For each petri-dish, seven milliliters of different Ni solutions [0 (control), 24, 70, 140 and 190 ppm] or Ni solutions that were previously treated with Azolla were added. Once the radicle had grown to around 2 mm, the percentage of germination was recorded on the fourth day of germination. Germination parameters and biochemical analyses were determined on the seventh day of germination.

Pot experiment (vegetative growth and yield stage)

The experiment was carried out in the autumn (November, 2022) at the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Helwan University. The sieved clay was mixed well with sieved clean sand. In wide-mouthed glazed pots of diameter 70 cm, 5 kg of clay-sand soil was added. The pots were divided into two groups; each group involved five treatments. The first group was represented by the original Ni solutions, including water (0 (control), 24, 70, 120, 190 ppm). The second group was represented by the Azolla-treated-Ni solutions, including water (0 (control), 24, 70, 120 and 190 ppm). Each treatment was represented in triple (n = 3). After 30 days of sowing, the plants were collected for growth metrics and biochemical analysis. After about 6 months, the grain yield was recorded.

Biochemical analyses

Enzyme activity assay

Hydrolases

Double-distilled water was used to grind a known weight of germinated maize seeds into a paste, which was subsequently centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C at 4000 rpm. The enzyme assay was conducted using the clear supernatant solution according to Zeid24. α-amylase (E.C. 3.2.1.1) and protease enzyme (E.C.3.4) activities were measured according to Bergmeyer25. For amylase, half milliliter of soluble starch in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 ml of double-distilled water, and 0.5 ml of enzyme extract made up the tested combination. One milliliter of the coloring reagent (1% dinitrosalisylic acid) was added to the mixture after a ten-minute incubation time at 25 °C and the mixture was then heated in a water bath for ten minutes before cooling in an ice bath. Double-distilled water was added to the mixture to make 10 ml, and a spectrophotometer (CE 1010) was used to detect the color density at 546 nm. For protease, 1 ml of casein (1%) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and 1 ml of enzyme extract made up the assaying mixture. The reaction was stopped after an hour of incubation at 37 °C with the addition of 2 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid, and the mixture was then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. According to Lowry et al.26, the supernatant’s soluble peptide content was calculated. Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3).

Antioxidant enzymes extraction

The supernatant that was used to evaluate enzyme activity was prepared according to Castillo et al.27. In a prechilled pestle and mortar, 0.5 g of fresh leaf material was homogenized with 10 ml of ice-cold phosphate buffer (Na/KP), pH 6.8. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 6000 rpm at 4 °C after being filtered through cheesecloth. Catalase (EC 1.11.1.6) activity was assessed according to the Góth28. The assaying mixture contained 0.2 ml of the enzyme extract and 1 ml of H2O2 (65 mM H2O2 in Na/KP, pH 7.4). By adding 1 ml of ammonium molybedate (4 g/l), the reaction was stopped after an incubation period of 4 min at 25 °C. Using a UV spectrophotometer (6405 UV/Vis), the generated color’s absorbance was determined at 405 nm.

For peroxidase activity, peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.7) activity was assessed according to the Yamane et al.29 method. The assaying mixture contains 0.2 ml 30% H2O2, 0.5 ml 8 mM guaicol, and 2.2 ml 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer. After pouring the assaying mixture into a clean quartz cuvette, the reaction was started by adding 0.1 ml of enzyme extract and mixing right away. The cuvette was put inside the UV spectrophotometer (6405 UV/Vis) to track absorbance changes for up to three minutes at 470 nm.

Chemical analysis

Photosynthetic pigments content and measurement of gas exchange

The Metzener et al.30 approach, as modified by Lichtenthaler31, was used to estimate the pigment content. Fresh leaves of a given weight were homogenized in 85% acetone. After 20 min of centrifugation at 4000 rpm and 4 °C, the pigment-containing supernatant was diluted to a specific volume with 85% acetone. Using a spectrophotometer and 85% acetone as a blank, the supernatant was measured at two different wave lengths on the spectrophotometer (CE 1010): 645 nm and 664 nm. Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3). The pigments were measured in mg g−1 Dwt of tissue. According to the following formulae, the concentrations of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b were determined:

\({\text{Chlorophyll}}\,{\text{a}}\,=\,10.3{\text{ E}}664--0.918{\text{ E}}645,{\text{ Chlorophyll b}}\,=\,19.7{\text{ E}}645--3.87{\text{ E}}664\)

The gaseous exchange of each control and treated maize plant was measured by a portable photosynthesis system (LCpro-SD, ADC BioScientific, Hoddesdon, UK) with a standard 2 × 3 cm2 leaf chamber. The pots were well watered a day before measurements. The measurements were carried out on fully expanded leaves (3 leaves). The measurements were carried out in ambient light at a leaf temperature of 23 °C. The photosynthetic parameters were measured after 30 days of cultivation. The measured attributes include the photosynthetic rate (A), stomatal conductance (Gs), internal CO2 (Ci) and evaporation rate (E).

Total soluble sugars

Fresh leaves (0.1 g) were crushed with 5 ml of ethanol and centrifuged at 4 °C at 4000 rpm for 10 min. Then, the total soluble sugars were determined using the anthrone technique by Umbriet et al.32. Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3).

Total soluble proteins

The Lowry et al.26 method used for total soluble proteins determination. A sample of the extract was treated with one millilitre of freshly mixed (1:1 v/v) solutions of 2% sodium carbonate in 4% sodium hydroxide and 0.5% copper sulphate in 1% sodium tartarate. The mixture was allowed to sit at room temperature for 10 min before adding 0.1 ml of Folin reagent. After 30 min, the optical density at 700 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (CE 1010). Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3).

Proline

Proline was extracted and estimated via the Bates et al.33 method by using an acid-ninhydrin reagent in glacial acetic acid.

Lipid peroxidation (Malondialdehyde content, MDA)

Monodehydroascorbate (MDA) was measured by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction to determine the level of lipid peroxidation as described by Doblinski et al.34. Fresh plant material (0.5 g) was homogenized in 10 ml of 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min. Four milliliters of thiobarbituric acid (0.5%) were added to 2 ml of the supernatant. At 95 °C, the previous mixture was heated for 30 min. Then, the mixture was cooled in an ice bath and centrifuged at 10,000g MDA equivalents were calculated using the Heath and Packer35 equation:

\({\text{MDA equivalents }}\left( {{\text{nmol c}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 1}}} \right)\,=\,1000{\text{ }}\left[ {\left( {Abs{\text{ }}532 - {\text{ }}Abs{\text{ }}600\,{\text{nm}}} \right)/155} \right].\)

Permeability plasma membranes (total electrolyte leakage)

The electrolytic conductivity of fresh leaves segments (10), 2.5 g, in 25 ml of deionized water (for 5 h) and after boiling (30 min) was measured by a conductivity meter. Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3). According to Zwiazek and Blake’s36 explanation, the relative permeability of the root.

Electrolytic conductivity of solution at 5 h before heating × 100.

Electrolytic conductivity of solution after heating.

Hydrogen peroxide content

According to Velikova et al.37 hydrogen peroxide content was determined. Fresh plant material (0.5 g) was homogenized in an ice bath with 5 ml of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid. The homogenate was centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm. The supernatant was used to determine the H2O2 content by using a buffered potassium iodide (KI) reagent on a spectrophotometer at 390 nm. Three replicates of each determination were made (n=3).

Phenolic and flavonoid compounds

Phenolics were determined according to Savitree et al.38 by using a Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. The content of the total flavonoids was estimated by the ZhiShen et al.39 method, by mixing the extract with NaNO2, a 10% AlCl3 solution, and a 1% NaOH solution. Three replicates of each determination were made (n = 3).

Determination of Nickel content

A known weight of plant material was ashed and digested with nitric acid (HNO3)40, for subsequent determination by Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (MPAES, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA 95051, United States). The translocation factor (TF) was used to estimate the translocation of Ni from the root to the leaves and seeds of maize41 as follows: TFleaf = C plant leaves/C plant roots.

Electron microscopy examination of Azolla pinnata cells

Stained sections were examined using a JEOL—JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope at 70 kV at Al-Azhar University’s Regional Centre for Mycology and Biotechnology (RCMB)42. The samples were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, rinsed in phosphate buffer, and post-fixed in potassium permanganate solution (0.1 g in 10 ml distalled water) for 5 min at room temperature. The samples were dehydrated in an ethanol series ranging from 10 to 90% for 15 min in each alcohol dilution and finally with absolute ethanol for 30 min. Samples were infiltrated with epoxy resin and acetone through a graded series until they were finally pure resin. Sample capsules were placed in an oven at 40 °C for 2 days to be sure that all the acetone had evaporated. Ultrathin Sect. (70 nm) were collected on copper grids. Sections were then double stained in uranyl acetate, followed by lead citrate.

Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA (Tukey, post-hoc) was applied to assess the difference among each group’s means. Variations in the germination, growth parameters, enzymes activity and metabolite concentrations, Ni concentration and yield components under different Ni stress levels with and without Azolla were carried out by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA I), and the mean values of three replicates were compared by a Tukey multiple comparison test at a 5% probability level. When the differences were significant, a post-hoc test (Tukey test at P < 0.05) was applied using SPSS (SPSS base 15.0 user’s guide, Chicago: SPSS 523 Inc.).

Results

Nickel ion concentration was measured before and after Azolla treatment (Fig. 1); its concentration was 0, 24, 70, 140 and 190 ppm in the prepared NiCl2 solutions at 0, 100, 300, 500 and 1000 ppm concentrations before Azolla treatment. Azolla treatment reduced its concentration to become 0, 10, 30, 70 and 125, respectively. The removal efficiency percentage of Ni by Azolla was 58.3, 57.1, 50.0 and 34.2% for 24, 70, 140 and 190 ppm Ni-solutions, respectively. Azolla absorbed Ni ions from the external Ni polluted solutions and accumulated them in the vacuole, appearing as Ni deposits adsorbed on the Azolla’s cell wall (Fig. 2B,C) by transmission electron microscope (TEM) examination. The control cell appeared with no Ni deposits and a clear vacuole (Fig. 2A). The healthy Azolla cells appeared with normal chloroplasts and nuclei (Fig. 3A), while the Azolla incubated in Ni solutions (190 ppm) was damaged (Fig. 3B), appearing with an abnormal cell wall and disruption of organelles.

The impact of untreated and Azolla-treated Ni-contaminated water on the germination of maize seeds

The current study found that increasing Ni concentration up to 190 ppm in the germination medium resulted in a progressive decrease in germination%, accompanied by a significant (at p < 0.05) reduction in hydrolytic enzymes activity, total soluble sugars and protein content (Table 1). Concerning the activity of the antioxidant enzymes, peroxidase (POX) and catalase (CAT) activities were increased at all Ni concentrations (Supplementary material S1), reaching their maximum activity at 190 ppm. Allowing the maize seeds to germinate in Ni-solutions previously treated with Azolla significantly decreased the inhibitory effect of Ni on the germination percentage, hydrolytic enzymes activity compared to un-treated ones (Table 1). The increment percentage in germination was 5, 23, 12 and 41% at 24, 70, 140 and 190 ppm Ni concentrations, respectively. The percentage of changes in germination parameters in response to Azolla treatment is represented in Fig. 4. The highest percentage of changes in the hydrolase’s activity and content of soluble sugars and proteins was at the highest concentration of Ni (190 ppm). The percentage of changes in germination parameters indicates the positive efficiency of Azolla in removing Ni from polluted solutions.

Growth parameters

All measured growth parameters (lengths, fresh and dry masses of maize roots and shoots) were obviously (p < 0.05) reduced with increasing Ni concentration. On the other side, Azolla-treated Ni-solutions amended the growth measurements of the plants (Table 2). Applying Azolla showed significant improvements for the shoot and root of maize compared to the untreated solutions, especially for fresh weights.

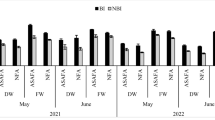

Photosynthetic pigments and efficiency

Application of different Ni-solutions negatively affected the chlorophyll a and b content (Table 3) and the total Chl content showed the same trend for each individual Chl. Additionally, increasing Ni concentration in the growing soil led to a significant decline in the measured photosynthetic activity traits expressed as photosynthetic rate (A), stomatal conductance (Gs) and evaporation rate (E) (Table 3). The lowest A and Gs were observed at the highest Ni concentration. In contrast, applying Azolla recovered the photosynthetic pigment content and photosynthetic rate (Table 3). Maximal recovery of chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity was observed at 190 ppm Ni (Fig. 5), where these values exceed one hundred.

The percentage of change in total chl and photosynthetic capacity traits A (photosynthetic rate), Gs (stomatal conductance), E (transpiration rate) in response to Azolla pinnata treatment (the percentage difference between untreated and Azolla-treated Ni solutions effect on photosynthetic activity parameters).

Oxidative stress (H2O2 and MDA content)

H2O2 and MDA have accumulated in maize leaves under Ni-induced stress, resulting in membrane dysfunction and increasing ion leakage (Table 4). Lipid peroxidation, as measured by MDA content, peaked at 190 ppm of Ni, indicating the hazards of high H2O2 levels. Proline was also accumulated in maize leaves as a protective compound upon the increase in Ni concentration (Table 4). Proline was increased threefold in maize leaves in response to the high Ni concentration (190 ppm) compared to the control.

The application of Azolla-treated Ni solutions reduced the accumulation of H2O2 and its destructive effect on the plasma membrane by lipid peroxidation (LPOX) in maize leaves. The proline accumulation was retained by Azolla-treated Ni solutions to become 1.54 mM g−1 F Wt, compared to 2.89 at 190 ppm of Ni.

Increasing the Ni concentration in the soil was accompanied by increasing the maize leaf content of antioxidant compounds (phenolics, flavonoids and total antioxidant capacity) and antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase (CAT) and peroxidases (POX)) (Table 5).

Antioxidant defense system (enzymatic and non-enzymatic)

Treating Ni solutions with Azolla recovered the content of phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant enzymes activity. The activity of POX and CAT reached 4.20 and 18.46 mg min−1g−1 F Wt, respectively, compared to 4.31 and 22.46 at untreated 190 ppm of Ni solution (Table 5). The percentage of changes for antioxidant compounds (phenolics, flavonoids) and the total antioxidant capacity revealed negative values, indicating they were positively affected by Azolla-treated Ni solutions (Fig. 6).

Nickel concentration

In general, Ni concentration and percentage significantly (p < 0.05) increased in roots, leaves and grains with increasing Ni concentration in applied solution (Supplementary material S1). The highest concentration of Ni was observed in leaves, while the lowest concentration was in grains. The increment of translocation factor (TF ˃1) of Ni from roots to leaves (Fig. 7) by increasing Ni levels indicates the tendency of Ni to be accumulated in the leaves. Upon treating Ni solution with Azolla, the Ni content and percentage in roots, leaves, and seeds were significantly (p ≤ 0.05) reduced (Supplementary material S1). The concentration of Ni reached zero in grains at the Azolla-treated Ni-24 ppm concentration and the translocation factor of Ni from root to leaf was decreased. The translocation factor was less than or equal to one at low concentrations of Ni (0 and 24 ppm Ni solution) (Fig. 7).

Yield components

The current results revealed a significant (p < 0.05) reduction of the maize yield components with an elevation of Ni concentrations (Table 6). The number and weight of grains per ear, the number of grains per plant, and the weight of 100 grains are the main components of grain yield, which are measured. However, the most affected yield parameter was the weight of 100 grains at 190 ppm Ni, where it verified zero. Zooming on using Azolla-treated solutions, all the components of grain yield were enhanced by the application of Azolla-treated Ni solutions on maize (Table 6).

It was found to be a positive relationship between growth parameters, total Chl, photosynthetic efficiency and yield (Fig. 8). However, those previous parameters were negatively correlated with H2O2 content and its destructive consequences (lipid peroxidation and electrolyte leakage). In addition, the antioxidant defense component was also negatively correlated with growth factors (particularly after Azolla treatment).

Discussion

The removal or reduction of contaminants (organic or inorganic) has a great interest globally; focusing on the protection of agricultural land43. Maize productivity loss mainly affected by the accumulation of heavy metals in soil44. Phyto-remediation is an economically and environmentally valuable application to address heavy metal contamination in soil by using plants to remove toxins. Macrophytes are more applicable for this purpose because of their quicker growth and greater biomass productivity45. Because of their capacity to hyperaccumulate heavy metals, they may be a confident phytoremediators for metal contaminated industrial and sewage waste water.

The incubated Azolla in Ni solutions was damaged showing an abnormal cell wall and disruption of organelles after five days. The same results were observed by Benaroya et al.46, where lead (Pb) precipitates were observed in the vacuoles of A. filiculoides mesophyll cells as black, dense deposits under a light and transmission electron microscope in the cells of fronds treated with Pb. This might be explained by the existence of specialized ligands that sequester and chelate metal ions in Azolla cells47. Plants have well-defined heavy metal-binding ligands known as phytochelatins (PCs) and metallothioneins (MTs), according to Joshi et al.48. Consequently those chelators, PCs, chelate tightly with metal ions forming complexes and collect them in vacuoles. That is why the heavy metal application greatly elevated MT2 and PCS1 gene expression patterns in Azolla, indicating their involvement in metal-remediation ability in a polluted area49.

Arif et al.50 demonstrated that heavy metals are, firstly, adsorbed in a cationic form with the negative cell wall of Azolla cells due to the presence of cellulose, pectins, and other ion exchangers. Secondly, they adsorbed on the cell wall. Finally, they accumulate in the cell51.

The reduction in seed germination percentage because of increasing the Ni ions in the surrounding medium could be attributed to its effect on the embryo viability, since this reduction was accompanied with a reduction in the activity of amylases and proteases that hydrolyze the complex stored food (starch and protein) to simple soluble compounds (sugars and amino acids), which supply the embryo axis for growth. Heavy metal ions, such as Ni may be inhibitors for the hydrolytic enzyme activity. In the same way, Zhi et al.52 demonstrated the reduction of germination under Ni stress.

The increment in activity of the antioxidant enzymes, peroxidase (POX) and catalase (CAT) at all Ni concentrations indicates an increase in cellular oxidative stress. Raising their activities neutralizes and counters the detrimental effects of reactive species. Similarly, Sethy and Ghosh53 found that the high levels of heavy metals in the germinating medium lead to disruption of cellular homeostasis, triggering oxidative stress including alterations in enzymes of the antioxidant defense system. Plant cells are equipped with enzymatic mechanisms to eliminate or reduce ROS-damaging effects54.

The activity of the hydrolytic enzymes was recovered by removing Ni ions from the surrounding medium by Azolla treatment, increasing the embryo supply with soluble sugars and amino acids necessary for its growth, and increased the germination percentage of maize seeds. Ahmeda and El-Mahdya55 mentioned that boosting of amylase activity enhances the mobilization of reserves from seed storage as endosperms or cotyledons for partitioning into embryo. Moreover, Azolla treatment reduced the increased activity of POX and CAT in the germinating seeds at all Ni concentrations, indicating a reduction in ROS production. Feng et al.56 reported that regulating antioxidant enzyme activities in plants leads to cellular redox balance and prevents cell damage.

Nickel level increasing in the soil considered toxic for maize because it uptakes and accumulates Ni in roots, leaves and grains. Thereby significant decline of the growth of maize was observed especially at higher concentrations of Ni. Nickel toxic effects including the excessive release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause a significant reduction in maize growth and functioning. The oxidative stress may lead to a decline in photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a and b) and activity in Ni-treated leaves by impacting chlorophyll synthesis enzymes. Similarly, Kumar et al.57 indicated that the decrease in the content of chlorophyll is a consequence of Ni toxicity. Magnesium in Chl may be substituted by Ni, which destroys Chl and thylakoid membranes in cabbage leaves and wheat shoots, respectively58. Ni reduced Rubisco synthesis and activity, reduced transport electrons to PSII59, and restricted Calvin cycle, resulting in a low photosynthesis rate, affecting agricultural plant growth and economics. Excessive Ni exposure may result in non-specific photosynthetic limitations in plants, either directly or indirectly60. Ni inhibits electron transport from pheophytin to plastoquinone QA and Fe to plastoquinone QB by altering the structure of carriers such plastoquinone QB and reaction center proteins. Ni ions reduced cytochromes b6f and b559, ferredoxin, and plastocyanin levels in thylakoids, resulting in lower electron transport efficiency61. Heavy metal stress causes the production of methylglyoxal (MG), which is a highly reactive cytotoxic alpha-oxoaldehyde compound that interferes with the plant’s normal metabolic activity62.

Increasing Ni concentration in soil led to increasing H2O2 and MDA in maize leaves, resulting in membrane dysfunction, increasing ion leakage because of lipid peroxidation. The Ni atom enhances H2O2 production by converting solvents into proton sources. Nickel (Ni3+) enrich facilitates the reaction intermediates *O, *OH, and *OOH, as well as the transfer of electrons throughout the reaction, enabling the production of hydrogen peroxide63. Nevertheless, when Ni and Co united with Fe2+, Fe2+−H2O2-mediated lipid peroxidation is encouraged in the occurrence of Ni2+ and is repressed in the occurrence of Co2+64. Lipid peroxidation, expressed by the MDA content, reflects the hazardous effect of the high levels of H2O2. High MDA (malondialdhyde) content results from the oxidation of the cellular membrane components by nickel, resulting in a high level of lipid peroxidation. This indicated membrane disorganization, so its leakiness has increased, followed by metabolic disturbance. Many authors proved the same outcome in their experiments, such as Rizwan et al.65 and Altaf et al.66 on rice. Comparable with other metals, Ni has a higher degree of lipid peroxidation due to its higher mobility in plants67. MDA accumulation and its negative influence on plant biomass and nutritional balance are attributed to ROS overproduction, which induces oxidative stress. This effect is considered a common response in maize plants to Cd68 and Ni stress. By the same way, Kumar et al.69 showed the raising of H2O2 and MDA under Cr stress in H. annuus L.

Proline has accumulated threefold in maize leaves, as a protective compound, upon increasing Ni concentration to 190 ppm. Osmotic adjustment metabolites (especially proline) and the antioxidant system have a significant role in cell protection against metal toxicity. Osmotic adjustment metabolites help to maintain the turgor pressure of the cell and are considered a metal chelator according to Bashir et al.70. They are involved in protein stabilization, direct scavenging of ROS, intracellular redox homeostasis balance (e.g., NADP+/NADPH and GSH/GSSG ratios), and cellular signaling pathways71. Increasing the Ni concentration in the soil was accompanied by increasing the maize leaf content of phenolics, flavonoids and total antioxidant capacity, as well as the antioxidant enzymes POX and CAT, to prevent the oxidative stress. Metal ions breakdown lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) by hemolytic breakage of the O–O link, producing lipid alkoxyl radicals that trigger free radical reactions. Phenolic antioxidants prevent lipid peroxidation by trapping the lipid alkoxyl radical. The activity of molecules is determined by their structure, as well as the amount and location of their hydroxyl group72.

Maize plants exposed to Ni stress significantly buildup phenolics, phytoalexins, and activated antioxidant enzymes such as CAT and POXs, as well as enzymes controlling phenylpropanoid and isoflavonoid biosynthesis, which are thought to be important regulators of stress tolerance73. Along with the accumulation of H2O2, phenolics, especially flavonoids, act as H2O2 scavengers74. Flavonoids create stable complexes with heavy metal ions, preventing oxidative stress from developing75. CAT may help in the defense against H2O2 accumulation, which was previously reported in the current study. This result was in harmony with the results obtained by67 on maize. The enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities has a crucial role in overcoming Ni stress, and Ni treatments significantly influence enzymatic activities76. It was suggested that antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, CAT, and APX) activity is higher in tolerant species of Solanum lycopersicum L. (under Pb stress) than those sensitive, indicating their vital role under metal stress77.

To provide safe and nutritious agricultural products, sustainable agriculture is essential. Heavy metal contaminated agriculture lands have a deleterious impact on crop growth, development, and production, indicating a challenge for sustained agriculture78. So, the mitigation of the Ni-affected soil and the prevention of Ni from entering agricultural environments are critical to overcoming this challenge. This issue recommends a variety of remediation methods to recover the heavy metal-contaminated soil. Many studies deal with the Ni remediation by Jatropha curcas and Pongamia pinnata79, while others used biochar and ryegrass80. In the current study, we used Azolla for Ni remediation from soil to restore the environmental quality. Azolla has significant features that make it a better plant system for phytoremediation than many other macrophytes. In the present work, Azolla treated Ni-contaminated irrigation water protected maize leaves by decreasing ROS (H2O2) generation and re-establishing membrane configuration and photosystem activity by increasing chlorophyll content and carbon dioxide assimilation. Thus, plants respond biochemically by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, improving growth metrics. This result was supported by Shedeed and Farahat81 study on the beneficial role of Azolla under Co and Cd stress.

Focusing on the percentage of changes in the measured parameters (during germination and vegetative growth), the calculated data emphasizes the impact of the different treatments, indicating the crucial role of Azolla in mitigating the toxicity of Ni on maize plants during germination and vegetative growth. Azolla, a free-floating, fast-growing, nitrogen-fixing pteridophyte, appears to be an outstanding option for heavy metal removal, disposal, and recovery from damaged aquatic environments82.

The tendency of Ni to accumulate in the maize leaves is more than the root was also observed in the Amjad et al.67 study, where they found that the translocation factor of Ni from root to leaf increased at a Ni concentration of 40 mg l−1 in maize hybrid Pioneer. The accumulation of Ni ions in the maize leaves indicates the impact of this heavy metal on metabolic activities. Amjad et al.67 confirmed an increase in Ni content in shoots and roots by increasing Ni concentration in maize. Ni is absorbed by roots via the iron (Fe) absorption transporter Iron-regulated transporter 1 (IRT1) and subsequently translocated (translocation factor ˃ 1) to shoots via the xylem83. IREG2 knockdown reduces root Ni while increasing shoot Ni, indicating that IREG2 may influence the efficiency of Ni translocation from roots to aerial parts84.

The reduction in maize yield with elevation of Ni concentrations could be attributed to the nutrient imbalance, because of the reduction of photosynthesis, as well as the stomatal conductance and evaporation rate that affect water and nutrient absorption by roots. Yield loss poses a substantial hazard to global food safety, hence it is critical to maximize crop yield potential in both normal and stressed situations. Nickel induced crop yield reduction due to the disturbance of nutrient absorption by roots in the presence of Ni85. Reduced yields under Ni stress have been recorded in mungbean86 and Hibiscus sabdariffa87. Photosynthesis in heavy metal-stressed plants decreased and the nitrogen content in the roots and leaves decreased in mungbean and chickpea88. So, this nutrient imbalance negatively affects the grain development in maize. Azolla-treated Ni solutions increased CO2 fixation compared to the untreated Ni solutions so the grain yield parameters would be improved. Recent research has shown compelling evidence that boosting photosynthetic efficiency via various systems may compromise a route to enhance agricultural production potential. Photosynthesis drives many biological activities such as crop production89.

Conclusion

Although plants need nickel as a crucial element for ideal growth, excess Ni in growing medium are harmed maize by the high disturbance range of physiological activities such as germination, growth, photosynthesis, enzymatic activities and yield, especially at high concentrations of Ni ions [190 ppm]. Nickel induced the lipid oxidation by releasing high rates of H2O2, destabilizing membranes in the cell and chloroplast. That influences the structural and functional integrity of chloroplast membrane, affecting electron transport chain and carbon fixation. Non-enzymatic (phenolics and flavonoids) and enzymatic (POX and CAT) antioxidant systems functioned as efficient scavenging system, preventing distribution of ROS to prevent further damage in the cell under Ni stress. Ni accumulated in leaves in higher concentration, showing translocation factor more than unity (TF ˃ 1) for root-leaf. Azolla treatment recovered the metabolic disruption in maize caused by Ni toxicity. Azolla-treated Ni-solutions enhanced growth parameters, photosynthesis and yield. Thus, Azolla is cheap and applicable strategy for purifying heavy metal-contaminated water. Thus, one of our future prospects to use Azolla with mixed heavy metal polluted irrigation water and give a complete picture of translocation, partitioning and toxicity of different heavy metals in plants.

Data availability

Data is provided within a supplementary information file besides the main manuscript file.

References

Yan, A. et al. Phytoremediation: a Promising Approach for Revegetation of Heavy Metal-Polluted Land. Front. Plant. Sci.11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00359 (2020).

Boateng, T. K., Opoku, F. & Akoto, O. Heavy metal contamination assessment of groundwater quality: a case study of Oti landfill site, Kumasi. Appl. Water Sci.9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-0915-y (2019).

Ma, K. et al. Effect of nickel on the germination and biochemical parameters of two rice varieties. Fresenius Environ. Bull.29 (2), 956–963 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Legacy of anthropogenic lead in urban soils: co-occurrence with metal(loids) and fallout radionuclides, isotopic fingerprinting, and in vitro bioaccessibility. Sci. Total Environ.806, 151276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021 (2022).

Khan, I. et al. Identifcation of novel rice (Oryza sativa) HPP and HIPP genes tolerant to heavy metal toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.175, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.03.040 (2019).

Kumar, A. et al. Mechanistic overview of metal tolerance in edible plants: A physiological and molecular perspective Mirza Hasanuzzaman, Majeti Narasimha Vara Prasad. In Handbook of Bioremediation 23e47 (Elsevier, 2021).

Kumar, A. et al. Khan, A. Bhatia Nickel in terrestrial biota: Comprehensive review on contamination, toxicity, tolerance and its remediation approaches. Chemosphere. 275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.12999 (2021).

Antoniadis, V. et al. Rinklebe J Trace elements in the soil-plant interface: phytoavailability, translocation, and phytoremediation–a review. Earth Sci. Res.171, 621–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.06.005 (2017). Get rights and content.

WHO. Permissible Limits of Heavy Metals in soil and Plants (World Health Organization, 1996).

Awasthi, S., Chauhan, R. & Srivastava, S. S. The importance of beneficial and essential trace and ultratrace elements in plant nutrition, growth, and stress tolerance. Plant Nutrition and Food Sec. In the Era of Climate Change. Elsevier, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822916-3.00001-9 (2022).

Manzoor, Z. et al. Transcription factors involved in plant responses to heavy metal stress adaptation. Plant. Pers. Global Clim. Changes. Elsevier (221-231). https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324 (2022).

Bishnoi, N. R., Sheoran, I. S. & Singh, R. Effect of cadmium and nickel on mobilisation of food reserves and activities of hydrolytic enzymes in germinating pigeon pea seeds. Biol. Plant.35 (1993).

Mustafa, A. et al. Nickel (Ni) phytotoxicity and detoxification mechanisms: A review. Chemosphere. 328(4), 328 138574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138574 (2023).

Ghazanfar, S. et al. Physiological effects of nickel contamination on plant growth. Nat. Volat .Essen. Oils. 8 (5), 13457–13469 (2021).

Li, Z. G. Methylglyoxal and glyoxalase system in plants: old players, New concepts. Bot. Rev.82, 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-016-9167-9 (2016).

Mishra, N. et al. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defense mechanisms. Front. Plant. Sci.14https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1110622 (2023).

Khan, I., Iqbal, M., Ashraf, M. Y., Ashraf, M. A. & Ali, S. Organic chelants-mediated enhanced lead (pb) uptake and accumulation is associated with higher activity of enzymatic antioxidants in spinach (Spinacea Oleracea L). J. Hazard. Mater.317, 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat (2016).

Li, S., Yang, W., Yang, T., Chen, Y. & Ni, W. Z. Effects of cadmium stress on leaf chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis of Elsholtzia argyi: a cadmium accumulating plant. Inter J. Phyto. 17 (1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2013.828020 (2015).

Nedjim, B. Phytoremediation: a sustainable environmental technology for heavy metals decontamination. SN Appl. Sci.3 (286). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04301-4 (2021).

Rai, P. Heavy metal phytoremediation from aquatic ecosystems with special reference to macrophytes. Int. J. Phyto. 39, 697–753 (2009).

Lasat, M. M. Phytoextraction of metals from contaminated soil: a review of plant/soil/metal interaction and assessment of pertinent agronomic issues. J. Hazard. Subst. Res.2, 1–25 (2000).

Lombi, E., Zhao, F. J., Wieshammer, G., Zhang, G. & McGrath, S. P. In situ fixation of metals in soil using bauxite residue: biological effects. Environ. Pollut. 118, 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0269-7491(01)00295-0 (2001).

Malenica, N., Dunić, J. A., Vukadinović, L., Cesar, V. & Šimić, D. Genetic approaches to enhance multiple stress tolerance in Maize. Genes12(11), 1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12111760

Zeid, I. M. Response of Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) to exogenous putrescine treatment under salinity stress. Pak J. Biol. Sci.7, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2004.219.225 (2004).

Bergmeyer, H. U. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis 2 edn (Academic, 1974).

Lowry, O., Rosebrough, N., Farr, A. L. & Randall, R. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem.193, 265–275 (1951).

Castillo, F. J., Celardin, F. & Greppin, H. Peroxidase assay in plants: interference by ascorbic acid and endogenous inhibitors in Sedum and Pelargonium enzyme extracts. Plant. Growth Regul.2, 69–75 (1984).

Góth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta. 196, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(91)90067-m (1991).

Yamane, K., Kawabata, S. & Fujishige, N. Changes in activities of SOD, catalase and peroxidases during senescence of Gladiolus florets. J. Jpn Soc. Hortic. Sci.68, 798–802 (1999).

Metzner, H., Rau, H. & Senger, H. Untersuchungen zur Synchronisierbarkeit Einzelner Pigmentmangel-Mutanten Von Chlorella. Planta. 65, 186–194 (1965).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Plant Cell Membranes, Elsevier, 350–382 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1

Umbriet, W. W. et al. Monometric technique: a manual description method applicable to study of describing metabolism. Burgess Publishing Co., 239 (1959).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil.39, 205–207 (1973).

Doblinski, P. M. F. et al. Peroxidase and lipid peroxidation of soybean roots in response to p-coumaric and p-hydroxybenzoic acids. Braz Arch. Biol. Technol.46, 193–198 (2003).

Heath, R. L. & Packer, L. Photo peroxidation in isolated chloroplast, Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.125, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003- (1968).

Zwiazek, J. J. & Blake, T. J. Early detection of membrane injury in black spruce (Piceamariana). Can. J. Res.21, 401–404. https://doi.org/10.1139/x91-050 (1991).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Plant. Sci.151, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1 (2000).

Savitree, M., Isara, P., Nittaya, S. L. & Worapan, S. Radical scavenging activity and total phenolic content of medicinal plants used in primary health care. J. Pharm. Sci.9, 32–35 (2004).

Zhishen, J., Mengcheng, T. & Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem.64, 555–559 (1999).

Malavolta, E., Vitti, G. C. & Oliveira, S. A. Avaliação do Estado Nutricional de Plantas (International Plant Nutrition Institute, 1997).

Allevato, E. et al. Arsenic accumulation in grafted melon plants: role of rootstock in modulating root-to-shoot translocation and physiological response. Agronomy. 9, 828 (2019).

Amin, B. H. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and biological investigation of new mixed‐ligand complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem.34https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5689 (2020).

Hashem, I. A. et al. Potential of rice straw biochar, sulfur and ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) in remediating soil contaminated with nickel through irrigation with untreated wastewater. Peer J.12 (8). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9267 (2020). e9267.

Saleem, M. H. et al. Silicon Fertigation regimes attenuates cadmium toxicity and phytoremediation potential in two maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars by minimizing its uptake and oxidative stress. Sustainability14, 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031462

Saralegui, A. B., Willson, V., Caracciolo, N., Piol, M. N. & Boeykens, S. P. Macrophyte biomass productivity for heavy metal adsorption. J. Environ. Manag. 289, 112398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112398 (2021).

Benaroya, R. O., Tzin, V., Tel-Or, E. & Zamski, E. Lead accumulation in the aquatic fern Azolla filiculoides. Plant. Physiol. Biochem.42, 639–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.010 (2004).

Gavanji, S., Doostmohammadi, M. & mojiri, A. In silico prediction of metal binding sites in Metallothionein Proteins. Appl. Sci. Rep.1 (2), 26–29 (2014).

Joshi, R., Pareek, A. & Singla-Pareek, S. L. Plant Metallothioneins. Plant Metal Inter 239–261 (Elsevier, 2016).

Talebi, M., Tabatabaei, B. E. S. & Akbarzadeh, H. Hyperaccumulation of Cu, Zn, Ni, and cd in Azolla species inducing expression of methallothionein and phytochelatin synthase genes. Chemosphere. 230, 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.098 (2019).

Arif, N. et al. Influence of high and low levels of Plant-Beneficial Heavy Metal ions on Plant Growth and Development. Front. Environ. Sci.4https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2016.00069 (2016).

Saygideger, S., Gulnaz, O., Istifli, E. S. & Yucel, N. Adsorption of cd(II), Cu(II) and ni(II) ions by Lemna minor L.: Effect of physicochemical environment. J. Hazard. Mater.126, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.06.012 (2005).

Zhi, Y. et al. Influence of heavy metals on seed germination and early seedling growth in Eruca sativa Mill. Am. J. Plant. Sci.6, 582–590. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2015.65063 (2015).

Sethy, S. K. & Ghosh, S. Effect of heavy metals on germination of seeds. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med.4 (2), 272–275. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.116964 (2013).

Devi Chinmayee, M. et al. A comparative study of heavy metal accumulation and antioxidant responses in Jatropha curcas L. IOSR J. Environ. Sci.8 (7), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.9790/2402-08735867 (2014).

Ahmeda, A. A. & El-Mahdya, A. A. Improving seed germination and seedling growth of maize (Zea mays, L.) seed by soaking in water and moringa oleifera leaf extract. Curr. Chem. Lett.11, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ccl.2022.2.005 (2022).

Feng, D. et al. Heavy metal stress in plants: ways to alleviate with exogenous substances. Sci. Total Environ.897, 165397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165397 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. Nickel toxicity alters growth patterns and induces oxidative stress response in sweet potato. Front. Plant. Sci.13https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls (2022).

Gajewska, E., Skłodowska, M., Słaba, M. & Mazur, J. Effect of nickel on antioxidative enzyme activities, proline and chlorophyll contents in wheat shoots. Biol. Plant.50, 653–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2012.07.001 (2006).

Küpper, H. & Andresen, E. Mechanisms of metal toxicity in plants. Metallomics. 8, 269–285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097810 (2016).

Shahzad, B. et al. Role of 24-epibrassinolide (EBL) in mediating heavy metal and pesticide induced oxidative stress in plants: a review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.147, 935–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.09.066 (2018).

Mohanty, N., Vass, I. & Demeter, S. Copper toxicity affects Photosystem II Electron Transport at the secondary Quinone Acceptor, QB. Plant. Physiol.90 (1), 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.90.1.175 (1989).

Nahar, K. et al. Polyamine and nitric oxide crosstalk: Antagonistic effects on cadmium toxicity in mung bean plants through upregulating the metal detoxification, antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 126, 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.026 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Tuning ni 3+ content in Ni 3 S 2 to Boost Hydrogen Peroxide Production for Electrochemical. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.63 (20). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.4c00436 (2024).

Repetto, M. G., Ferrarotti, N. F. & Boveris, A. The involvement of transition metal ions on iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Arch. Toxicol.84 (4), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-009-0487-y (2010).

Rizwan, M. et al. Nickel stressed responses of rice in Ni subcellular distribution, antioxidant production, and osmolyte accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res.24, 20587–20598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9665-2 (2017).

Altaf, M. M. et al. Effect of Vanadium on Growth, Photosynthesis, reactive oxygen species, antioxidant enzymes, and cell death of Rice. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nut. 20, 2643–2656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-020-00330-x (2020).

Amjad, M. et al. Nickel Toxicity Induced changes in Nutrient Dynamics and antioxidant profiling in two maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids. Plants. 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9010005 (2019).

Abbas, S. et al. Deciphering the impact of Acinetobacter sp. SG-5 strain on two contrasting Zea mays L. cultivars for Root exudations and distinct PhysioBiochemical attributes under cadmium stress. J. Plant. Growth Regul.42, 6951–6968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-023-10987-0 (2023).

Kumar, D. A., Dhankher, P. B., Tripathi, D., Seth, C. S. & R. C., & Titanium dioxide nanoparticles potentially regulate the mechanism(s) for photosynthetic attributes, genotoxicity, antioxidants defense machinery, and phytochelatins synthesis in relation to hexavalent chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. J. Hazard. Mater.454, 131418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131418 (2023).

Bashir, S. S. et al. Plant drought stress tolerance: understanding its physiological, biochemical and molecular mechanisms. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip.35, 1912–1925. https://doi.org/10.1080/13102818.2021.202061 (2021).

Liang, X., Zhang, L., Natarajan, S. K. & Becker, D. F. Proline mechanisms of stress survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal.19, 998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars (2013).

Milic, B. L., Djilas, S. M. & Canadanovic, B. J. M. Antioxidantive activity of phenolic compounds on metal-ion break down of lipid peroxidation system. Food Chem.61, 443–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(97)00126-X (1998).

Sharma, A. et al. Response of phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of polyphenols in plants under abiotic stress. Molecules. 24, 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132452 (2019).

Jańczak-Pieniążek, M., Cichoński, J., Michalik, P. & Chrzanowski, G. Effect of Heavy Metal Stress on Phenolic compounds Accumulation in Winter Wheat plants. Molecules. 28 (1), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010241 (2023).

Khlestkina, E. K. The adaptive role of flavonoids: emphasis on cereals. Cereal Res. Commun.41, 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1556/CRC.2013.0004 (2013).

Kumar, K., Debnath, P., Singh, P. & Kumar, N. An overview of Plant Phenolics and their involvement in abiotic stress tolerance. Stresses. 3, 570–585. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses3030040 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Impact of foliar application of syringic acid on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under heavy metal stress-insights into nutrient uptake, redox homeostasis, oxidative stress, and antioxidant defense. Front. Plant. Sci.25, 13, 950120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.950120 (2022).

Gupta, S. & Seth, C. S. Salicylic acid alleviates chromium (VI) toxicity by restricting its uptake, improving photosynthesis and augmenting antioxidant defense in Solanum lycopersicum L. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 27 (11), 2651–2664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-021-01088-x (2021).

Borah, P. A. B., Rangan, L. C. & Mitra, S. Phytoremediation of nickel and zinc using Jatropha curcas and Pongamia pinnata from the soils contaminated by municipal solid wastes and paper mill wastes. Environ. Res. 219, 115055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.115055

Hashem, I. A. et al. Potential of rice straw biochar, sulfur and ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) in remediating soil contaminated with nickel through irrigation with untreated wastewater. PeerJ. 12(8), e9267. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9267 (2020).

Shedeed, Z. A. & Farahat, E. A. Alleviating the toxic effects of Cd and Co on the seed germination and seedling biochemistry of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using Azolla pinnata. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int.30 (30), 76192–76203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27566-1 (2023).

Arora, A., Saxena, S. & Sharma, D. K. Tolerance and phytoaccumulation of chromium by three Azolla species. World J. Micro Biotechnol.22, 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-005-9000-9 (2006).

Nishida, S., Kato, A., Tsuzuki, C., Yoshida, J. & Mizuno, T. Induction of Nickel Accumulation in response to Zinc Deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Inter J. Mol. Sci.16, 9420–9430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16059420 (2015).

Merlot, S. et al. The metal transporter PgIREG1 from the hyperaccumulator Psychotria gabriellae is a candidate gene for nickel tolerance and accumulation. J. Exp. Bot.65, 1551–1564. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru025 (2014).

Rahi, A. et al. Toxicity of Cadmium and nickel in the context of applied activated carbon biochar for improvement in soil fertility. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.29 (2), 743–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.035 (2022).

Ahmad, M. S. A., Hussain, M., Saddiq, R. & Alvi, A. K. Mungbean: A Nickel Indicator, Accumulator or Excluder? Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.78, 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-007-9182-y (2007).

Aziz, E. E., Gad, N. & Badran, N. M. Effect of cobalt and nickel on plant growth, yield and flavonoids content of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Aust J. Basic. Appl. Sci.1, 73–78 (2007).

Yusuf, M., Fariduddin, Q., Hayat, S., Ahmad, A. & Nickel An overview of uptake, essentiality and toxicity in plants. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.86, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-010-0171-1 (2011).

Muhie, S. H. Optimization of photosynthesis for sustainable crop production. CABI Agric. Biosci.3, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-022-00117-3 (2022).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.I., conception, supervision and reviewing, G.E.K., experiments performing, data collecting, data analysis, data analysis S.Z.A., conception, experiments performing, data collecting, data analysis and writing manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. We confirm that this manuscript that not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal. All Authors have approved the manuscript and agree with submission to this journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All the methods were performed in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and regulations. The plants were cultivated at Helwan University, Faculty of Science. So, it does not need any permission because there is no collection of samples.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeid, I., Ghaly, E.K. & Shedeed, Z.A. Azolla pinnata as a phytoremediator: improves germination, growth and yield of maize irrigated with Ni-polluted water. Sci Rep 14, 22284 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72651-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72651-1