Abstract

Methylmercury (MeHg) is a well-known neurotoxicant that induces various cellular functions depending on cellular- and developmental-specific vulnerabilities. MeHg has a high affinity for selenol and thiol groups, thus impairing the antioxidant system. Such affinity characteristics of MeHg led us to develop sensor vectors to assess MeHg toxicity. In this study, MeHg-mediated defects in selenocysteine (Sec) incorporation were demonstrated using thioredoxin reductase 1 cDNA fused with the hemagglutinin tag sequence at the C-terminus. Taking advantage of such MeHg-mediated defects in Sec incorporation, a cDNA encoding luciferase with a Sec substituted for cysteine-491 was constructed. This construct showed MeHg-induced decreases in signaling in a dose-dependent manner. To directly detect truncated luciferase under MeHg exposure, we further constructed a new sensor vector fused with a target for proteasomal degradation. However, this construct was inadequate because of the low rate of Sec insertion, even in the absence of MeHg. Finally, a Krab transcriptional suppressor fused with Sec was constructed and assessed to demonstrate MeHg-dependent increases in signal intensity. We confirmed that the vector responded specifically and in a dose-dependent manner to MeHg in cultured cerebellar granule cells. This vector is expected to allow monitoring of MeHg-specific toxicity via spatial and temporal imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

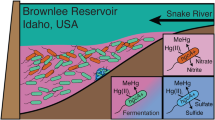

Methylmercury (MeHg) is a well-known neurotoxic contaminant in the environment. The risk of MeHg-induced neurotoxicity depends on various cellular conditions, including differences in tissue and cell characteristics, exposure age (fetal, childhood, or adulthood), and exposure levels1. For instance, Minamata disease, a MeHg intoxication-induced neurological disorder found in Japan, shows two characteristic clinical forms (fetal type and adult type), depending on the exposure age. Fetal type Minamata disease, caused by exposure to MeHg in utero, is characterized by extensive brain lesions. In contrast, primary lesions in the adult type, caused by MeHg intoxication during adulthood, involve the central nervous system (cerebellum, cerebrum, and dorsal root ganglia) and peripheral sensory nervous system2,3. The mechanisms underlying such cell- and age-dependency of MeHg toxicity in humans remain unknown despite various studies on the subject4,5,6.

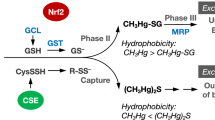

MeHg is easily incorporated into proteins to form a MeHg-cysteine complex because MeHg has a high affinity for the sulfur atom in thiol groups. Oral consumption of the MeHg-cysteine complex in seafood results in its absorption by the intestines7. Because the MeHg-cysteine complex conformationally mimics the essential amino acid methionine, it can be transported into the brain via amino acid transporters for methionine in the blood-brain barrier8,9,10,11. MeHg accumulates within the brain in the case of continuous ingestion of contaminated food. An understanding of the specific effects of MeHg on the interactions of biomolecules in different cellular contexts and developmental phases is essential to elucidate the mechanisms of MeHg-mediated neuronal degeneration. Monitoring the time when MeHg toxicity begins will be meaningful to increase the understanding of and protection against MeHg toxicity12.

Selenoproteins contain selenocysteine (Sec) residues, often referred to as the 21st amino acid. The structure of Sec is similar to that of cysteine, with the sulfur in the thiol (R-SH) group substituted by selenium (R-SeH). Selenols have a lower pKa (≈5.2) than thiols (≈8.3) and are more reactive toward Hg13,14,15. Additionally, selenoprotein impairment is a hallmark of MeHg toxicity. Humans have a selenoproteome composed of 25 selenoproteins, including antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidases (GPx1, GPx2, GPx3, GPx4, and GPx6) and thioredoxin reductases (TrxR1, TrxR2, and TrxR3)16,17,18. Therefore, dysfunction of selenoproteins disrupted by MeHg results in a cellular redox imbalance, leading to the occurrence of oxidative stress13,19.

MeHg interacts with selenoproteins via three mechanisms: directly with proteins and indirectly through their transcription and expression processes. MeHg conjugates with selenol in selenoproteins, potentially impairing enzyme activities mediated by selenol13. In addition to MeHg, electrophilic stress activates Nrf2-mediated transcription, which upregulates cellular defenses against toxicants20.

The UGA codon that encodes Sec is shared with a stop codon. Therefore, depletion of selenium can induce termination of protein synthesis by recognizing the UGA codon of Sec as a nonsense codon, known as a premature termination codon (PTC), during selenoprotein translation21.

For instance, in the case of GPx1, the gpx1 gene comprises two exons, with the TGA codon for Sec located 105 bp upstream of the splicing sites. The exon junction complex at the splicing sites can recruit the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) complex22,23. NMD is an mRNA quality control mechanism that is active when the PTC is located sufficiently upstream of the exon–exon junction. Therefore, NMD controls the quality of GPx1 via Sec incorporation24. Similar to selenium depletion, under MeHg exposure, the NMD complex recognizes the UGA codon of Sec as a PTC, resulting in a reduction of GPx1 mRNA (Fig. 1A)21,25.

Methylmercury (MeHg) induces partial fragments of selenoproteins. (A) Schematic representation of selenoprotein synthesis with or without MeHg25. The selenocysteine (Sec) insertion sequence (SECIS) recruits SECIS binding protein (SBP) and Sec, and TGA is recognized as a Sec codon. Depletion of Sec and resulting in a premature termination codon (PTC) at TGA. For GPx1, an exon junction complex (EJC) downstream of the PTC recruits nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) factors. The PTC of TrxR1, which is not followed by EJCs, is hypothesized to produce a truncated form of GPx1 under MeHg exposure. (B) GPx1, which was fused with a FLAG tag and an HA tag, was exogenously expressed in Cos-7 cells and analyzed via sodium dodecyl sulfate poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by western blotting. The SECIS was derived from GPx1 gene. An αHA antibody confirmed its full-length form. After exposure to 6 µM MeHg for 24 h, the signals from both antibodies decreased. (C) TrxR1 was fused with an N-terminal FLAG tag and a C-terminal HA tag. The αFLAG antibody could recognize both full-length and truncated TrxR1, while the αHA antibody recognized only full-length TrxR1. Cos-7 cells were transfected with FLAG-TrxR1-HA and exposed to MeHg (0, 6 µM) for 24 h. The cells were lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. The SECIS was derived from TrxR1 gene. The full-length TrxR1 signal (αHA) decreased in a MeHg-dependent manner. (D) Cos-7 cells expressing FLAG-TrxR1-HA were treated with 6 µM MeHg for 24 h in the presence or absence of 50 µg/ml cycloheximide (Chx), a protein synthesis inhibitor. The full-length form of TrxR1 was unaffected by MeHg during Chx treatment.

The three mechanisms by which MeHg interacts with selenoproteins are closely related. For example, selenophosphate synthetase 2 (Sps2), which is involved in Sec synthesis, is itself a selenoprotein26. Direct modification of Sps2 by MeHg will impair its enzymatic activity and deplete Sec. Nrf2-mediated transcription usually upregulates cellular defenses against toxicants, but MeHg-mediated deficiency of GPx and other selenoproteins compromises the stress defense mechanism. Thus, these relationships are responsible for the characteristics of MeHg compared to other toxicants.

In this study, we first selected TrxR1 cDNA as a basic sensor construct to monitor MeHg cytotoxicity. The active site of TrxR includes a redox-active selenothiol/selenosulfide and is known to be sensitive to MeHg13. Because the Sec in TrxR1 is localized in the last exon, it is theorized that TrxR1 cDNA might produce a truncated protein under Sec deficiency. Additionally, a decrease in TrxR1 activity caused by MeHg exposure has been shown in vitro and in vivo13,25,27. We explored several constructs that exhibited MeHg-induced impairment of selenoprotein translation. Finally, we developed a MeHg sensor vector and then validated its specific and dose-dependent responses to MeHg in cultured cells.

Results

MeHg-mediated impairment of selenoprotein synthesis

To verify the synthetic model of the NMD pathway, GPx1 cDNA, including its intron, was transfected into Cos-7 cells. The cell lysates were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blotting (Fig. 1B). Exogenous GPx1 expression was suppressed under MeHg treatment, as shown in the model. A hypothetical model of the non-NMD pathway was then examined (Fig. 1C). TrxR1 is a selenoprotein that is not influenced by the exon junction complex. Because TrxR1 consists of 499 amino acids, with a single Sec located at residue 498, the potential PTC of TrxR1 lacks splicing sites for the exon junction complex. Usuki and colleagues previously reported that MeHg impaired TrxR activity despite its enhanced expression. However, the TGA codon can be read through by SerRNA28, but TrxR-498Ser loses this catalytic function, which is necessary to distinguish the full-length form from the truncated form. Therefore, a FLAG-TrxR1-HA cDNA construct was designed for expression analysis (Fig. 1C). The amino terminal-fused FLAG tag allowed detection of both the full-length and truncated forms, while the carboxyl terminal-fused HA tag allowed detection of only the full-length form. Then, transfected Cos-7 cells were treated with MeHg (0, or 6 µM) for 24 h. MeHg only reduced the HA signal while leaving the FLAG signal unchanged (Fig. 1C). To examine the effect of MeHg on TrxR1 metabolism, we treated cells with cycloheximide (Chx), which acts as a protein synthesis inhibitor. Under Chx treatment, MeHg did not affect the full-length form of TrxR1 (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that MeHg impairs Sec incorporation for full-length selenoprotein expression but does not impair total expression in the non-NMD pathway.

MeHg sensitivity of a reporter containing Sec

On the basis of our initial results, we speculated that the compromised Sec incorporation caused by MeHg could be used to construct a sensor vector. A TrxR1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA construct was generated by fusing GFP, which is a compact protein suitable for fusion protein expression, to the carboxyl terminus. MeHg reduced the fluorescence signal intensity of GFP in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Additionally, MeHg specifically produced a greater reduction in fluorescence signals with this construct than diethyl maleate (DEM), another electrophile (Fig. 2B). TrxR1-C-GFP, which included a Sec and the first Met, flanking amino acids 494–499 in TrxR1, also displayed a decreased signal after MeHg exposure. These data suggest that a Sec residue is sufficient to detect MeHg toxicity. However, the GFP signal exhibited a high background because of the excitation light and autofluorescence. Consequently, an artificial Sec mutant, Luc-391Sec (luciferase with a Cys391Sec substitution), was created as a sensor vector. The Cys-391 residue is not required for luciferase activity but modifies this signal29. In contrast to the GFP vector, luciferase generated luminescence from the reaction of luciferin and ATP, yielding a high signal to noise ratio, but luciferase was relatively large in the fusion protein. Exposure to MeHg directly or indirectly reduced the luciferase activity of Luc-391Sec in a dose-dependent manner, as indicated by a high signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 2C). As a result, a Luc-391Sec sensor vector was produced that showed reduced signal intensity in a MeHg-dependent manner.

Reporters containing Sec show sensitivity to MeHg via decreased signals. (A) TrxR1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) constructs were generated by fusing TrxR1 with GFP. The SECIS was derived from TrxR1. The TrxR1-C-GFP construct comprised the first Met followed by residues 496Gly-Cys-Sec-499Gly of TrxR1 and GFP. The full-length TrxR1-GFP did not show a fluorescence signal, whereas the truncated version did. Cos-7 cells were transfected with the indicated cDNA constructs and then treated with MeHg (0, 2, 6, or 20 µM) for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were lysed and subjected to a fluorescence assay. Both TrxR1-GFP and TrxR1-C-GFP exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in signal intensity upon MeHg exposure. (B) Cos-7 cells were transfected with the indicated cDNA constructs and then treated with 20 µM MeHg or 100 µM diethyl maleate (DEM) for 24 h. Both TrxR1-GFP and TrxR1-C-GFP exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in signal intensity upon MeHg exposure. (C) The Luc-491Sec construct contained the luciferase gene with a Sec substitution for 491Cys. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. Luc-491Sec exhibited a decrease in signal intensity upon treatment with different MeHg concentrations (0, 1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 µM for 24 h), resulting in a lower background than that of TrxR1-GFP.

High concentrations of toxicants can lead to cell death. This reduced bioavailability could also potentially decrease luciferase activity in a MeHg-independent manner. To address this nonspecificity, we aimed to develop new sensor vectors showing an increase in signal intensity in a MeHg-dependent manner. The Luc-Sec-ornithine decarboxylase (odc) construct comprised a fusion of luciferase, Sec, and odc, which is a target for proteasomal degradation30. Theoretically, the full-length form of Luc-Sec-odc should be degraded by odc, while the truncated form without odc should remain unchanged. However, when Luc-Sec-odc was expressed in Cos-7 cells, a strong signal was observed both with and without MeHg exposure (Fig. 3A). The Luc-Cys-odc construct, which is a substituted mutant, lost its luciferase activity and was sensitive to MG-132, a proteasomal inhibitor. These findings suggest that the odc sequence following the Sec was not adequately expressed.

Monitoring of truncated forms of selenoprotein failed to indicate MeHg exposure. (A) Structures of the Luc-Sec (or Cys)-odc constructs. Ornithine decarboxylase (odc), a target for proteasome degradation, was expected to suppress luciferase activity under full-length protein expression. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. Contrary to expectations, Luc-Sec-odc showed robust signals both with and without MeHg exposure (0 or 20 µM for 24 h). In contrast, Luc-Cys-odc showed no luciferase activity. MG-132 (10 µM for 24 h), a proteasome inhibitor, alleviated the reduction in the Luc-Cys-odc signal. (B) Structures of the FLAG-TrxR1-HA, Cys, and ΔSECIS constructs. The SECIS was derived from TrxR1. The construct with a Cys mutation provided a more robust signal than did TrxR1 in an αHA blot (full) and an equivalent signal in an αFLAG blot (full and truncated). Compared with the total TrxR1, only a small fraction of full-length TrxR1 was expressed.

Therefore, proportions of the full-length and truncated forms of selenoproteins were evaluated. TrxR1-Cys was constructed with a substitution mutation of Sec498Cys, enabling 100% expression of the full-length form according to SDS-PAGE. In TrxR1-expressing Cos-7 cells, TrxR1 provided an equivalent signal to that of TrxR1-Cys on an αFLAG blot (Fig. 3B). In contrast, TrxR1 showed only weak signal intensity compared with TrxR1-Cys on an αHA blot. These data indicate that the full-length selenoprotein TrxR1 is much less abundant than total TrxR1.

Low-level Sec incorporation

Several potential factors responsible for the low level of full-length selenoprotein expression were investigated. First, the expression of other selenoproteins was studied. Selenoprotein N (SelN) is an endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensor protein31. Petit N and colleagues confirmed the expression of the full-length form of SelN at ~ 70 kDa using an antibody against the carboxyl terminal region of SelN32. SelN cDNA was transfected into Cos-7 cells, and western blotting was used to assess the protein levels (Fig. 4A). SelN expression was hardly detected at ~ 60 kDa under normal conditions but became evident at ~ 70 kDa with Cys substitution. This evidence highlights the importance of Sec incorporation in properly functioning selenoproteins.

Evaluation of various factors affecting Sec insertion. (A) Expression of selenoprotein N (SelN). In Cos-7 cells. The SECIS was derived from SelN. SelN cDNAs displayed a single-band signal. However, the molecular weight of this signal differed from that of the full-length protein, as confirmed by a mutant with a Cys substitution for Sec. (B) Expression of an artificial selenoprotein using several SECISs. C322U is a Tau mutant with a Sec substitution at Cys322 followed by the indicated SECIS. In Cos-7 cells, the C322U cDNAs expressed more of the truncated form than of the full-length form across each section. (C) Coexpression of SECIS binding protein 2 (SBP2) to enhance selenoprotein translation. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. Compared with its absence, SBP2 increased the full-length expression of C322U, but this increase was not dominant in the overall C322U population. (D) Selenoprotein expression with selenium supplementation. C322U was expressed in Cos-7 cells treated with various concentrations of sodium selenite (0, 10, 30, or 100 nM) for 24 h. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. The signals of the full-length form of C322U intensified with the addition of selenium, but they remained lower than those of the truncated form. (E) Sec incorporation under-regulated induction of selenoproteins. pTre-C322U comprised Tet response element (Tre) repeats and subsequent C322U cDNAs. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. The reverse tetracycline transactivator controlled C322U expression in a doxycycline (Dox)-dependent manner (0, 3, 10, 30, and 100 ng/ml Dox for 24 h). At lower Dox concentrations, the ratio of the full-length form to the truncated form of the construct was similar to that at high concentrations. (F) Expression of multi-Sec selP mutants. The N-terminal signal peptide regions were deleted from the expression constructs. All or most of the Sec residues were substituted with Cys residues. The SECIS was derived from SelP. The ratio of full-length SelP expression for the 1xSec mutant compared with that of the 0xSec (AllC) mutant was low but the 2xSec to 1xSec or 3xSec to 2xSec ratios were not. (G) Schematic diagrams of selenoprotein synthesis. Expression of selenoprotein genes in the Cos-7 cell system primarily follows the nonselenoprotein synthesis pathway.

Second, an artificial selenoprotein was used to evaluate the Sec insertion sequence (SECIS). The SECIS is essential for selenoprotein expression and is located in the 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of selenoprotein cDNAs33. Tau-C322U is a Tau protein mutant with a Sec substitution at Cys322, following the SECIS derived from individual selenoprotein genes. Tau was originally identified as a causative protein in Alzheimer’s disease and is unrelated to selenoproteins34. In Cos-7 cells, each SECIS from Toxoplasma gondii SelT (Tox), human TrxR, and SelP showed a deficient expression level of the full-length form compared with that of the truncated form (Fig. 4B)35. Therefore, the SECIS does not cause low-level Sec insertion despite its central role in selenoprotein synthesis.

Third, we investigated the coexpression of an exogenous SECIS binding protein, SBP2, an essential factor for Sec translation36,37. SECIS-SBP2 interactions recruit Sec-tRNA38,39. C322U and SBP2 cDNAs were cotransfected into Cos-7 cells. The expression of full-length C322U increased with SBP2 coexpression, but it was still much lower than that of the truncated form (Fig. 4C). Therefore, while SBP2 expression is practical for low-level Sec incorporation, it is insufficient for high-level Sec incorporation.

Next, additional selenium was provided for selenoprotein synthesis. The expression of full-length C322U was enhanced by sodium selenite treatment (at concentrations of 10, 30, and 100 nM), but the ratio of the full-length form to the total amount was still minimal (Fig. 4D). Thus, selenium supplementation was effective but not sufficient for adequate Sec incorporation.

We also explored the possibility that resource depletion could hinder successful Sec incorporation. pTre-C322U is a Tau-C322U mutant controlled by the Tet response element (TRE)40. Using a reverse tetracycline transactivator, doxycycline could induce Tau expression in a dose-dependent manner. Total Tau expression was successfully restricted at a low doxycycline concentration (10 ng/ml). Nevertheless, the ratios of full-length forms to truncated forms were very low, similar to the balance at a high concentration (100 ng/ml) (Fig. 4E). This result indicates that resources, including selene, SBP2, and other machinery, are abundant for selenoprotein expression, but completely different factors control low-efficiency Sec insertion.

The above mentioned observations raise the question of whether selenoproteins can function appropriately with low-efficiency Sec insertion, especially in SelP, a protein containing multiple Sec41. FLAG-Δ20-AllC-HA is a SelP mutant in which the signal peptide is deleted and all Sec residues are substituted with Cys. It is also fused with a FLAG tag at the amino terminus and an HA tag at the carboxyl terminus. Compared with that of AllC, the expression level with a single Sec at position 346 or two Sec residues at positions 353 and 355 was low for the full-length form (Fig. 4F). However, the expression of Sec 346/353/355 was moderate compared with that of Sec 346 or Sec 353/355. Moreover, Sec combinations including Sec 59, Sec 59/346, Sec 59/353/355, and Sec 59/346/353/355 had almost the same expression level as the full-length form with a single Sec 59. In summary, the second and subsequent Sec residues were processively inserted despite the inefficient insertion of the first Sec. These findings suggest a mechanism that controls the sorting of selenoproteins or non-selenoprotein synthesis at an early stage (Fig. 4G).

Krab-Sec/Luc as a MeHg sensor vector

Because of the difficulty of monitoring the induction of the truncated form of a construct as a MeHg sensor, we adopted a different strategy using a trans-repression factor. Krab-Sec was constructed from the TetR DNA binding domain, followed by Sec as a linker and the Krüppel-associated box (Krab) domain of zinc finger protein 354 A40. The luciferase gene was regulated by the Tre (Fig. 5A). Theoretically, full-length Krab-Sec could inhibit luciferase expression but not when exposed to MeHg. Initially, the promoters of Krab and luciferase expression were validated (Fig. 5B). For Krab-Sec expression, both the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and the EF1α promoter, which are functional for stable expression of transcription factors against gene silencing, were examined42. Krab-Cys (Cys), including a Cys substitution for Sec driven by each promoter, predictably reduced luciferase activity compared with that of the control mock vector (-). Only Krab-Sec driven by the CMV promoter, not by the EF1α promoter, successfully decreased pTre-Luc activity.

Designs of Krab-Sec/Luc sensors to detect MeHg toxicity via an increased signal. (A) Structures of the MeHg sensor manifest an increasing signal. The TetR DNA binding domain interacts with the Tet response element (Tre), with Krab functioning as a transcriptional repressor. In the absence of MeHg, the TetR-Sec-Krab (Krab-Sec) protein suppresses luciferase activity. In the presence of MeHg, a truncated TetR may lose its repressive function, thus elevating the luciferase signal. The SECIS was derived from Toxoplasma gondii SelT. (B) Combinations of promoters for the MeHg sensor. Krab-Sec (or Krab-Cys) contained the cytomegalovirus (CMV) or EF1α promoter, while luciferase employed the CMV, SV40, or TK promoter. A luciferase assay was performed after transfecting Cos-7 cells with specific cDNA combinations. (C) The effect of additional Krab on the MeHg sensor was examined using Krabx2-Sec, which includes TetR, Sec, and a Krab tandem repeat. Cos-7 cells were transfected with pCT-Luc and Krab-Sec (or Krabx2-Sec) and subsequently subjected to a luciferase assay. (D) Sec locations in TetR-Krab. In Krab-Sec 2 or Krab-Sec 3, Sec is positioned at the + 7 or + 121 position of TetR-Krab. After transfection with specific cDNAs, a luciferase assay was performed.

Next, the CMV promoter, SV40 promoter, and TK promoter were evaluated to examine luciferase expression (Fig. 5B). In Cos-7 cells, both the SV40 and TK promoters showed moderate induction, which was anticipated for Krab-mediated repression. However, despite their moderate luciferase activity, the ratio of Krab-Sec (Sec) to mock vector (-) activity did not improve with the SV40 and TK promoters compared with that of the CMV promoter. Consequently, combinations of pCMV-Krab-Sec and pCMV-Tre-Luciferase (pCT-Luc) were chosen.

To enhance Krab-mediated gene suppression, we attempted to use a Krab-tandem construct and Sec at other positions in Krab. Krabx2-Sec is a tandem repeat of Krab fused with TetR and Sec and was predicted to intensify trans-repression. In contrast to the expectation, pCT-Luc activity was not inhibited by Krabx2-Sec (Fig. 5C). To optimize the Sec position, Krab-Sec 2 and Krab-Sec 3 were designed as mutants with Ser7Sec and Cys121Sec substitutions, respectively (Fig. 5D). Krab-Sec 2 did not suppress pCT-Luc activity in Cos-7 cells. Additionally, although Krab-Sec 3 could inhibit activity, this reduction was not superior to that achieved by Krab-Sec.

The sensitivity of Krab-Sec/Luc to MeHg was measured to validate the sensor vectors. Cos-7 cells transiently expressing Krab-Sec/Luc were treated with 20 µM MeHg for 24 h (Fig. 6A). MeHg exposure resulted in a 1.7-fold increase in luciferase activity compared with that in the untreated group. ERAI-Luc (an endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor) and Nrf2-Luc (an electrophile stress sensor) were used to compare the Krab-Sec/Luc construct with other sensors43,44. Treatment with tunicamycin, an endoplasmic reticulum stress inducer, for 24 h led to a 1.6-fold increase in luciferase activity in Cos-7 cells expressing ERAI-Luc. The efficiency of this sensor could be improved by low-dose plasmid transfection (×0.1 DNA), compensating for the weaker signal intensity. Exposure to DEM, an electrophile, for 24 h resulted in only a 1.3-fold increase in luciferase activity in cells expressing Nrf2-Luc. Additionally, this electrophilic stress sensor maintained sufficient efficacy with a lower plasmid DNA dose (×0.1 DNA).

Validation of the Krab-Sec-Luc MeHg sensor. (A) Comparison of the MeHg sensor with other toxic sensors. The ERAI-Luc and OKD-Luc sensors detect endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress, respectively. Cos-7 cells expressing these sensors were exposed to 6 µM tunicamycin (Tun), 100 µM diethyl maleate (DEM), or 20 µM MeHg for 24 h before being subjected to a luciferase assay. The amount of DNA used for transfection was either 100 ng or 10 ng (with 90 ng of mock plasmid DNA) of the indicated cDNA. (B) MeHg dose dependency of the Krab-Sec/Luc response. Cos-7 cells expressing Krab-Sec/Luc were treated with 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 25 µM MeHg for 24 h, followed by a luciferase assay. (C) Sustainability of the Krab-Sec/Luc signal for different durations of MeHg exposure. Cos-7 cells expressing Krab-Sec/Luc were treated with 20 µM MeHg for 8 (on day 1), 16, or 24 h (from day 1 to day 2) and then subjected to a luciferase assay. (D) Specificity of the Krab-Sec/Luc sensor for MeHg. Cos-7 cells expressing Krab-Sec/Luc were exposed to 400 µM H2O2, 100 µM DEM, 15 µM 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), 10 nM prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), 100 µM MnCl2, 10 µM sulforaphane (Sulf), 100 µM PbCl2, 100 µM CoCl2, 3 µM CdCl2, or 20 µM MeHg for 24 h. In cases where a reduction in cell death did not occur, the concentrations of each reagent were determined by bioavailability using cells that expressed luciferase driven solely by the CMV promoter. (E) Krab-Sec/Luc activity in cultured neurons. Krab-Sec/Luc was transfected into primary cultured cerebellar granule cells (CGCs), which were subsequently exposed to 0, 6, or 20 µM MeHg for 24 h. Krab-Sec/Luc exhibited a MeHg-dependent signal in CGCs. At a high MeHg concentration (20 µM), the CGCs died, leading to an absence of luciferase activity.

To validate the reproducibility and quantify the results, cells transfected with Krab-Sec/Luc were exposed to different doses of MeHg for varying durations. Krab-Sec/Luc-mediated luciferase activity increased in a dose-dependent manner upon exposure to 5 to 20 µM MeHg (Fig. 6B). According to a time-course analysis (8, 16, and 24 h), a shorter MeHg exposure (8 h) increased the luciferase activity, and longer exposures (16 and 24 h) did so even more efficiently (Fig. 6C).

The specificity of the MeHg sensor, among other electrophiles, was then addressed. In Cos-7 cells transfected with Krab-Sec/Luc, treatment with 100 µM DEM, 15 µM 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), 10 µM sulforaphane, 100 µM PbCl2 (Pb), or 100 µM CoCl2 (Co), as metal ions, did not increase pCT-Luc luciferase activity (Fig. 6D). DEM and 4-HNE are electrophiles, sulforaphane induces the oxidative stress response, and Pb and Co are metal ions. Exposure to other compounds, including 400 µM H2O2, 10 µM PGJ2, 100 µM MnCl2 (Mn), and 3 µM CdCl2 (Cd), enhanced luciferase activity but was less effective than exposure to MeHg. Conversely, higher-dose treatments with these oxidants reduced luciferase signals because of toxicity-mediated cell death.

The Krab-Sec/Luc construct was investigated in neurons as a potential MeHg sensor for future application in sensor vectors in the brain. Mouse cerebellar granule cells (CGCs) were transfected with Krab-Sec/Luc using calcium phosphate precipitation. Two days after transfection, the neurons were treated with 0, 6, or 20 µM MeHg for 24 h. The results showed that cells exposed to 6 µM MeHg exhibited increased luciferase activity compared with that in untreated cells. However, at 20 µM MeHg, the signal intensities decreased because of cell death (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

This study shows the inhibitory effect of MeHg on the incorporation of Sec during translation. Taking advantage of the deficiency in Sec incorporation, we created a cDNA encoding a reporter gene with a Sec substitution at Cys that is sensitive to MeHg exposure. Assessment of the truncated form of the selenoprotein demonstrated a high background of low-efficiency Sec incorporation in a cultured cell model. Then, Krab-Sec/Luc, a Krab transcriptional suppressor fused with Sec, was designed and exhibited increased signaling upon exposure to MeHg. These vectors were extensively evaluated regarding their responses to MeHg doses and specificity for MeHg in cultured cells and are expected to allow monitoring of MeHg-specific toxicity in vitro and in vivo, aiding spatial and temporal imaging.

MeHg can interact with and deplete Sec45. Usuki and colleagues previously reported that MeHg reduces GPx1 expression through NMD-mediated suppression of gpx1 mRNA25. The present study explored the non-NMD pathway of selenoproteins under MeHg exposure. We found that MeHg induces a truncated form of selenoproteins, including TrxR1 and other designed proteins (Figs. 1 and 4). Among selenoproteins, the Secs of TrxRs are notably located at the carboxyl terminal region. Truncated TrxR1 consists of amino acids 1–497 and lacks two amino acids at its active site, unlike the full-length form (amino acids 1–499). Anestål K and colleagues reported that truncated TrxR1 induces cell death46. This toxicity could occur in addition to the reduction and direct modification of full-length TrxR1, even upon exposure to low concentrations of MeHg.

The reporter Luc-Sec-odc did not function as a MeHg sensor because of the low efficiency of Sec incorporation (Fig. 3). TrxR1, SelN, SelP, and a designed Tau-C322U mutant gene also demonstrated a low level of Sec incorporation (Figs. 3 and 4). Mehta A and colleagues reported that the Sec incorporation rate of a designed Luc-Sec mutant was approximately 5–8% in vitro and 6–10 times lower in transfected cells47. They also highlighted the highly effective (~ 50%) processive incorporation of Sec in SelP. However, our results confirmed that total Sec incorporation was minimal because of ineffective incorporation of the first Sec (Fig. 4F). As a limitation of our study, we only examined the Sec incorporation of several selenoproteins in specific cells. Under these conditions, regular expression of selenoproteins cannot be guaranteed. Unknown mechanisms, possibly related to protein quality control, might enhance Sec incorporation efficiency for other selenoproteins in different contexts.

Sensor vectors facilitate the quantitative detection of intracellular stress responses that are otherwise difficult to observe. Various sensor vectors, including ERAI-Luc and Nrf2-Luc, have been developed43,44,48. ERAI-Luc detect ER stress- dependent alternative splicing of xbp1. Nrf2-Luc, reflects the Nrf2/Keap1 response to electrophile stress. Mice engineered with these vectors enable temporal and spatial monitoring of in vivo stress responses. The Luc-391Sec and Krab-Sec/Luc sensor vector designed for detect MeHg-dependent deficiency of Sec incorporation (Figs. 2 and 6). the disability of selenoproteins induced by MeHg is important due to the dysfunction of the defense mechanisms against electrophilic stress. These sensors for MeHg toxicity detection could also be applied to mouse models. Given that the symptoms of MeHg poisoning are primarily believed to be caused by central nervous system abnormalities, brain toxicity in the sensor mice could be visualized effectively. Nonetheless, potential challenges, such as the poor brain permeability of chemiluminescent reaction substrates, are expected. Fortunately, the CMV promoter in Krab-Sec/Luc is derived from an exogenous gene (Fig. 5). A change to another exogenous promoter, for example, the CAG promoter, might mitigate concerns related to detection sensitivity.

The Luc-391Sec showed decreased signals by MeHg at 1–20 µM for 24 h (IC50 = 3.3 µM, Fig. 2C), and the Krab-Sec/Luc showed increased signals by MeHg at 5–20 µM for 24 h (EC50 = 8.8 µM, Fig. 6B). The Krab-Sec/Luc is superior for MeHg-dependent increased signals but inferior for the lower sensitivity, to Luc-391Sec. This sensitivity issues can be attributed to the time delay necessary for the expression of Krab-Sec. Carvalho et al. reported MeHg toxicity in the purified protein system and in the cultured cell system13. MeHg inhibits the activity of recombinant TrxR1 purified from Escherichia coli at 5-100 nM for 5 min (IC50 = 19.7 nM). However, in the cultured cell (Hela cell) experiments, MeHg inhibits TrxR1 activity at 1–10 µM for 24 h (IC50 = 1.4 µM), and Trx activity at 1–20 µM for 24 h (IC50 = 6.7 µM). These difference from Luc-391Sec may be caused by the time for luciferase expression, cell densities or cell lines.

Exposure to MeHg primarily arises from the consumption of seafood. However, there are also reports of food being contaminated by other potentially toxic elements49,50,51, such as Cd, Pb, and As. This contamination suggests the possibility of coexposure along with MeHg. Combined toxicity is typically estimated using the concentration addition model to assess exposure to multiple toxic substances. Nonetheless, concerns persist regarding the potential synergistic effects of these toxicants in in vivo situations. In response to these concerns, it is imperative to set evaluation standards, categorize toxic substances, and measure their interactions during coexposure. Akiyama and colleagues chose reactive sulfur species as standards and revealed the cooperative effects of Cu and Cd on MeHg toxicity52,53. In the present study, Krab-Sec/Luc showed specificity for MeHg, among other oxidants (Fig. 6), and this construct is expected to be another standard to evaluate combined exposure to MeHg.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

MeHg was purchased from Kanto Chemical (Chuo-Ku, Tokyo, Japan). DEM was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Chuo-Ku, Tokyo, Japan). MG-132, lead chloride (Pb), cobalt chloride (Co), cadmium chloride (Cd), manganese chloride (Mn), ITS, and Ara C were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Chemical (Osaka, Osaka, Japan). Prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and tunicamycin (Tun) were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan). Cycloheximide (Chx), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), sulforaphane (Sulf), and anti-FLAG (M2) and anti-HA (3F10) antibodies were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Burlington, Massachusetts, United States of America). Anti-TrxR1 antibody (B-2) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, United States of America). Anti-βActin antibody (6D1) was purchased from Medical & Biological Laboratories (Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture

Cos-7 cells were purchased from KAC. The cells were cultured in Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America) supplemented with fetal bovine serum. The cells (2 × 104 cells for 96 well plate or 10 × 104 cells for 24 well plate) were transiently transfected with the indicated cDNA constructs using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 48 h, the cells were lysed in tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (TBS-Tx) for expression analysis, followed by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. Chemiluminescence images were acquired using a ChemiDoc Touch system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, United States of America). GFP-expressing cells were lysed with TBS-Tx for the reporter assay, and fluorescence signals were detected using a Fluoroskan system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells expressing luciferase were lysed and analyzed using a luciferase kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America). Luminescence was monitored using a Luminescencer system (ATTO, Osaka, Osaka, Japan).

CGCs were prepared from 7-day-old mouse pups. Dissociated CGCs were cultured in basal medium eagle (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 25 mM KCl and 10% fetal bovine serum from 1 to 3 days in vitro (DIV) and subsequently cultured in minimum essential media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing ITS and Ara C from 4 DIV onward. Primary cultured CGCs were transfected with the indicated cDNAs using the calcium phosphate precipitation method at 2 DIV.

MeHg, Pb, Co, Cd, Mn, and Sulf were dissolved in DDW for chemical stimulation. MG-132, Tun, and Chx were dissolved in DMSO. 4-HNE and PGJ2 were dissolved in ethanol. Chemical reagents were diluted in a culture medium at the indicated concentrations and administered to cells from 24 to 48 h after transfection (except for Fig. 6C). The corresponding solvents were added to equalize the amount of solvent across each sample.

CGC preparation

All animal experiments including CGC preparation were approved by the animal test committee at the National Institute for Minamata Disease (NIMD) and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals issued by the NIMD and the ARRIVE2.0 guidelines54.

cDNAs and promoter DNAs

cDNAs for FLAG-GPx1-HA with the 3’ UTR (NM_201397), FLAG-TrxR1-HA with the 3’ UTR (NM_182743), the SECIS of Toxoplasma gondii SelT (Tox SECIS) (XM_018782092), 3xHA, FLAG-SelN with the 3’ UTR (NM_020451), Tau (NM_005910), FLAG-SelP-HA with the 3’ UTR (NM_178297), TetR-Sec-Krab (NM_052798), and promoter DNAs, including 7xTre (pTre), EF-1a (pEF), and HSV-TK (pTK), were synthesized by Azenta (Burlington, Massachusetts, United States of America). pTre and pCMV-Tet3G were purchased from Promega. FLAG-TrxR1-HA, FLAG-SelN, Tau, FLAG-SelP-HA, and TetR-Sec-Krab were inserted into the multiple cloning site in the pCI-pur vector. The cDNA corresponding to amino acids 410–461 of odc (M10624) was synthesized by Fasmac. TrxR1-GFP and TrxR1-3xHA were generated by inserting GFP and 3xHA at the EcoRI-HA-SalI sites in FLAG-TrxR1-HA. Luciferase was inserted at the NheI and SalI sites in pCI-pur55,56,57. TrxR1-C-GFP, representing amino acids 494–499 of TrxR1-GFP, was generated by PCR. Luc-391Sec was generated by substituting Cys391 with Sec in luciferase using PCR and adding Tox SECIS at the SalI and NotI sites. Luc-Sec-odc was generated from the luciferase and odc sequences using PCR. The respective promoters of pTre-CMV, pTre-SV, and pTre-TK were inserted into the BglII-CMV promoter-HindIII sites in pCI-pur. The SelP-Δ20-AllCys combined mutant resulted from a deletion of the signal peptide comprising amino acids 1–20 of SelP and Cys substitutions at Sec 59/267/273/279/290/292/294/310/320/322/336/338/346/353/355/355/362/364, generated by PCR.

References

Fujimura, M. & Usuki, F. Cellular conditions responsible for methylmercury-mediated neurotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23137218 (2022).

Eto, K. Pathology of minamata disease. Toxicol. Pathol.25, 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/019262339702500612 (1997).

Harada, M., Akagi, H., Tsuda, T., Kizaki, T. & Ohno, H. Methylmercury level in umbilical cords from patients with congenital minamata disease. Sci. Total Environ.234, 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00255-7 (1999).

Fujimura, M. & Usuki, F. In situ different antioxidative systems contribute to the site-specific methylmercury neurotoxicity in mice. Toxicology. 392, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOX.2017.10.004 (2017).

Fujimura, M. & Unoki, T. Preliminary evaluation of the mechanism underlying vulnerability/resistance to methylmercury toxicity by comparative gene expression profiling of rat primary cultured cerebrocortical and hippocampal neurons. J. Toxicol. Sci.47, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.2131/JTS.47.211 (2022).

Unoki, T., Akiyama, M., Shinkai, Y., Kumagai, Y. & Fujimura, M. Spatio-temporal distribution of reactive sulfur species during methylmercury exposure in the rat brain. J. Toxicol. Sci.47, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.2131/JTS.47.31 (2022).

Harris, H. H., Pickering, I. J. & George, G. N. The chemical form of mercury in fish. Science301, 1203. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1085941 (2003).

Aschner, M. & Clarkson, T. W. Uptake of methylmercury in the rat brain: effects of amino acids. Brain Res.462, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(88)90581-1 (1988).

Kerper, L. E., Ballatori, N. & Clarkson, T. W. Methylmercury transport across the blood-brain barrier by an amino acid carrier. Am. J. Physiol.https://doi.org/10.1152/AJPREGU.1992.262.5.R761 (1992).

Mokrzan, E. M., Kerper, L. E., Ballatori, N. & Clarkson, T. W. Methylmercury-thiol uptake into cultured brain capillary endothelial cells on amino acid system L . J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.272, 1277–1284 (1995).

Simmons-Willis, T. A., Koh, A. S., Clarkson, T. W. & Ballatori, N. Transport of a neurotoxicant by molecular mimicry: the methylmercury-L-cysteine complex is a substrate for human L-type large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT) 1 and LAT2. Biochem. J.367, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20020841 (2002).

Khan, M. A. K. & Wang, F. Mercury-selenium compounds and their toxicological significance: toward a molecular understanding of the mercury-selenium antagonism. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.28, 1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.1897/08-375.1 (2009).

Carvalho, C. M. L., Chew, E. H., Hashemy, S. I., Lu, J. & Holmgren, A. Inhibition of the human thioredoxin system. A molecular mechanism of mercury toxicity. J. Biol. Chem.283, 11913–11923. https://doi.org/10.1074/JBC.M710133200 (2008).

Huber, R. E. & Criddle, R. S. Comparison of the chemical properties of selenocysteine and selenocystine with their sulfur analogs. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.122, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(67)90136-1 (1967).

Arnér, E. S. J. Selenoproteins-what unique properties can arise with selenocysteine in place of cysteine? Exp. Cell. Res.316, 1296–1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YEXCR.2010.02.032 (2010).

Kryukov, G. V. et al. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 300, 1439–1443. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1083516 (2003).

Labunskyy, V. M., Hatfield, D. L. & Gladyshev, V. N. Selenoproteins: Molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev.94, 739–777. https://doi.org/10.1152/PHYSREV.00039.2013 (2014).

Zoidis, E., Seremelis, I., Kontopoulos, N. & Danezis, G. P. Selenium-dependent antioxidant enzymes: Actions and properties of selenoproteins. Antioxidants (Basel).https://doi.org/10.3390/ANTIOX7050066 (2018).

Hirota, Y., Yamaguchi, S., Shimojoh, N. & Sano, K. I. Inhibitory effect of methylmercury on the activity of glutathione peroxidase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.53, 174–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-008X(80)90394-4 (1980).

Unoki, T. et al. Molecular pathways associated with methylmercury-induced Nrf2 modulation. Front. Genet.https://doi.org/10.3389/FGENE.2018.00373 (2018).

Moriarty, P. M., Reddy, C. C. & Maquat, L. E. Selenium deficiency reduces the abundance of mRNA for Se-dependent glutathione peroxidase 1 by a UGA-dependent mechanism likely to be nonsense codon-mediated decay of cytoplasmic mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol.18, 2932–2939. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.5.2932 (1998).

Zhang, J., Sun, X., Qian, Y., LaDuca, J. P. & Maquat, L. E. At least one intron is required for the nonsense-mediated decay of triosephosphate isomerase mRNA: A possible link between nuclear splicing and cytoplasmic translation. Mol. Cell. Biol.18, 5272–5283. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.9.5272 (1998).

Le Hir, H., Izaurralde, E., Maquat, L. E. & Moore, M. J. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20–24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J.19, 6860–6869. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBOJ/19.24.6860 (2000).

Sun, X., Moriarty, P. M. & Maquat, L. E. Nonsense-mediated decay of glutathione peroxidase 1 mRNA in the cytoplasm depends on intron position. EMBO J.19, 4734–4744. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBOJ/19.17.4734 (2000).

Usuki, F., Yamashita, A. & Fujimura, M. Post-transcriptional defects of antioxidant selenoenzymes cause oxidative stress under methylmercury exposure. J. Biol. Chem.286, 6641–6649. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.168872 (2011).

Guimarães, M. J. et al. Identification of a novel selD homolog from eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea: Is there an autoregulatory mechanism in selenocysteine metabolism?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A93, 15086–15091. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.93.26.15086 (1996).

Dalla Corte, C. L. et al. Effects of diphenyl diselenide on methylmercury toxicity in rats. Biomed. Res. Int.https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/983821 (2013).

Liu, Z. et al. Seryl-tRNA synthetase promotes translational readthrough by mRNA binding and involvement of the selenocysteine incorporation machinery. Nucleic Acids Res.51, 10768–10781. https://doi.org/10.1093/NAR/GKAD773 (2023).

Ohmiya, Y. & Tsuji, F. I. Mutagenesis of firefly luciferase shows that cysteine residues are not required for bioluminescence activity. FEBS Lett.404, 115–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00105-1 (1997).

Murakami, Y. et al. Ornithine decarboxylase is degraded by the 26S proteasome without ubiquitination. Nature. 360, 597–599. https://doi.org/10.1038/360597A0 (1992).

Chernorudskiy, A. et al. Selenoprotein N is an endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensor that links luminal calcium levels to a redox activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A117, 21288–21298. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.2003847117/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL (2020).

Petit, N. et al. Selenoprotein N: An endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein with an early developmental expression pattern. Hum. Mol. Genet.12, 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1093/HMG/DDG115 (2003).

Berry, M. J. et al. Recognition of UGA as a selenocysteine codon in type I deiodinase requires sequences in the 3’ untranslated region. Nature. 353, 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1038/353273A0 (1991).

Morris, M., Maeda, S., Vossel, K. & Mucke, L. The many faces of tau. Neuron. 70, 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEURON.2011.04.009 (2011).

Novoselov, S. V. et al. A highly efficient form of the selenocysteine insertion sequence element in protozoan parasites and its use in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 7857–7862. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.0610683104 (2007).

Copeland, P. R., Fletcher, J. E., Carlson, B. A., Hatfield, D. L. & Driscoll, D. M. A novel RNA binding protein, SBP2, is required for the translation of mammalian selenoprotein mRNAs. EMBO J.19, 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBOJ/19.2.306 (2000).

Low, S. C., Grundner-Culemann, E., Harney, J. W. & Berry, M. J. SECIS-SBP2 interactions dictate selenocysteine incorporation efficiency and selenoprotein hierarchy. EMBO J.19, 6882–6890. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBOJ/19.24.6882 (2000).

Fagegaltier, D. et al. Characterization of mSelB, a novel mammalian elongation factor for selenoprotein translation. EMBO J.19, 4796–4805. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBOJ/19.17.4796 (2000).

Tujebajeva, R. M. et al. Decoding apparatus for eukaryotic selenocysteine insertion. EMBO Rep.1, 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBO-REPORTS/KVD033 (2000).

Freundlieb, S. & Schirra-Mu Èller Hermann Bujard, C. A tetracycline controlled activation/repression system with increased potential for gene transfer into mammalian cells. J. Gene Med.1, 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199901/02)1:1 (1999).

Burk, R. F., Hill, K. E. & Selenoprotein P-expression, functions, and roles in mammals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1790, 1441–1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2009.03.026 (2009).

Gopalkrishnan, R. V., Christiansen, K. A., Goldstein, N. I., DePinho, R. A. & Fisher, P. B. Use of the human EF-1alpha promoter for expression can significantly increase success in establishing stable cell lines with consistent expression: A study using the tetracycline-inducible system in human cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res.27, 4775–4782. https://doi.org/10.1093/NAR/27.24.4775 (1999).

Iwawaki, T. & Akai, R. Analysis of the XBP1 splicing mechanism using endoplasmic reticulum stress-indicators. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.350, 709–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2006.09.100 (2006).

Oikawa, D., Akai, R., Tokuda, M. & Iwawaki, T. A transgenic mouse model for monitoring oxidative stress. Sci. Rep.https://doi.org/10.1038/SREP00229 (2012).

Sugiura, Y., Tamai, Y. & Tanaka, H. Selenium protection against mercury toxicity: high binding affinity of methylmercury by selenium-containing ligands in comparison with sulfur-containing ligands. Bioinorg. Chem.9, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3061(00)80288-4 (1978).

Anestål, K., Prast-Nielsen, S., Cenas, N. & Arnér, E. S. J. Cell death by SecTRAPs: Thioredoxin reductase as a prooxidant killer of cells. PLoS One.https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0001846 (2008).

Mehta, A., Rebsch, C. M., Kinzyi, S. A., Fletcher, J. E. & Copeland, P. R. Efficiency of mammalian selenocysteine incorporation. J. Biol. Chem.279, 37852. https://doi.org/10.1074/JBC.M404639200 (2004).

Iwawaki, T., Akai, R., Yamanaka, S. & Kohno, K. Function of IRE1 alpha in the placenta is essential for placental development and embryonic viability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106, 16657–16662. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.0903775106 (2009).

Khanverdiluo, S., Talebi-Ghane, E., Ranjbar, A. & Mehri, F. Content of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in various animal meats: A meta-analysis study, systematic review, and health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int.30, 14050–14061. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11356-022-24836-2 (2023).

Eissa, F., Elhawat, N. & Alshaal, T. Comparative study between the top six heavy metals involved in the EU RASFF notifications over the last 23 years. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOENV.2023.115489 (2023).

Chiocchetti, G., Jadán-Piedra, C., Vélez, D. & Devesa, V. Metal(loid) contamination in seafood products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.57, 3715–3728. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1161596 (2017).

Akiyama, M., Unoki, T. & Kumagai, Y. Combined exposure to environmental electrophiles enhances cytotoxicity and consumption of persulfide. Fundam Toxicol. Sci.7, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.2131/FTS.7.161 (2020).

Akiyama, M., Shinkai, Y., Yamakawa, H., Kim, Y. G. & Kumagai, Y. Potentiation of methylmercury toxicity by combined metal exposure: in vitro and in vivo models of a restricted metal exposome. Chemosphere. 299, 134374. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2022.134374 (2022).

Percie du Sert. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br. J. Pharmacol.177, 3617. https://doi.org/10.1111/BPH.15193 (2020).

Chalfie, M., Tu, Y., Euskirchen, G., Ward, W. W. & Prasher, D. C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 263, 802–805. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.8303295 (1994).

Nagai, T. et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol.20, 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/NBT0102-87 (2002).

de Wet, J. R., Wood, K. V., DeLuca, M., Helinski, D. R. & Subramani, S. Firefly luciferase gene: structure and expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol.7, 725–737. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.7.2.725-737.1987 (1987).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Atsuko Mori, Natsu Yoshiyama, and Mio Arimura for their technical assistance. We thank Lisa Kreiner, PhD, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS designed the study, the main conceptual ideas and the proof outline. AS conducted the experiments and collected the data. FU and MF aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. AS wrote the manuscript with support from FU and MF. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sumioka, A., Usuki, F. & Fujimura, M. Development of a sensor to detect methylmercury toxicity. Sci Rep 14, 21832 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72788-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72788-z