Abstract

Climate change is causing widespread impacts on seawater pH through ocean acidification (OA). Kelp forests, in some locations can buffer the effects of OA through photosynthesis. However, the factors influencing this variation remain poorly understood. To address this gap, we conducted a literature review and field deployments of pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) loggers within four habitats: intact kelp forest, moderate kelp cover, sparse kelp cover and barrens at one site in Port Phillip Bay, a wind-wave dominated coastal embayment in Victoria, Australia. Additionally, a wave logger was placed directly in front of the intact kelp forest and barrens habitats. Most studies reported that kelp increased seawater pH and DO during the day, compared to controls without kelp. This effect was more pronounced in densely populated forests, particularly in shallow, sheltered conditions. Our field study was broadly consistent with these observations, with intact kelp habitat having higher seawater pH than habitats with less kelp or barrens and higher seawater DO compared to barrens, particularly in the afternoon and during calmer wave conditions. Although kelp forests can provide local refuges to biota from OA, the benefits are variable through time and may be reduced by declines in kelp density and increased wave exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is having widespread impacts on coastal ecosystems through rising seawater temperatures, altered weather patterns and changes in seawater chemistry1. Since the beginning of the industrial revolution the sustained absorption of atmospheric CO2 by oceans has led to increased concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and lowered sea surface pH by approximately 0.1 unit, termed ‘ocean acidification’ (OA)2. OA is predicted to have widespread impacts on key taxa, commercial fisheries3, and other critical ecosystems services4,5. There is an increasing interest in understanding the role of marine macrophytes (such as macroalgae) in mitigating the effects of OA6,7.

Large brown seaweeds or kelps (orders Laminariales and Fucales) form extensive forests in temperate coastal reef systems worldwide8. Kelp forests can alleviate the impacts of OA by locally increasing pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) in seawater through the process of photosynthesis9,10,11. However, the effects of kelp forests on seawater chemistry vary diurnally9,10,11. During the day, kelps actively draw in DIC from the surrounding seawater through photosynthesis which increases seawater DO and pH while at night kelps respire resulting in declines in seawater DO and pH (Fig. 1). The ability of kelp forests to buffer OA, therefore, depends on whether net photosynthesis outweighs net respiration9,12,13.

There are, however many other abiotic and biotic factors that could influence a kelp forest’s ability to influence seawater chemistry9,13. Dense kelp forests can reduce seawater flow, internal motion and mixing within the centre of the forest and acceleration on the forest edge14,15. Longer seawater residence times within the centre of intact Macrocystis forests allows for increased uptake of DIC by kelp during the day, increasing local seawater DO and pH levels14. Studies have further suggested that the seawater pH is higher in the surface water of dense Macrocystis forests in sheltered waters compared to that of deeper or more exposed waters12,14,16. The ability of Macrocystis and other kelp forests to influence hydrodynamics and/or seawater chemistry could therefore be dampened by stressors which reduce densities of kelp or where the entire forest is removed through overgrazing by sea urchins (i.e. barrens habitat)12,17, or during periods of high wave exposure12,14,16.

Previous studies on the effects of kelp forests on seawater chemistry have shown mixed evidence that kelp forests can buffer the effects of OA. Some studies comparing seawater chemistry inside vs. outside of kelp forests demonstrate consistently higher pH and DO inside than outside kelp forests18, while others show temporally variable effects19 or no differences10,14. Much of the research on the effects of kelp forests on seawater chemistry has focused on Macrocystis forests (but see9,19,20). There is a clear need for further study to understand the key driver(s) of this variability, across a range kelp species. Here we conducted a literature review as well as field measurements at one site in Port Phillip Bay Victoria, Australia. Our aim was to assess how the varying abiotic and biotic characteristics of the dominate kelp forests in this region, primarily formed by Ecklonia radiata, influence seawater chemistry. Our prediction for the field measurements was that the benthic seawater pH and DO would be higher in E. radiata forests compared to barrens habitats, primarily due to photosynthetic draw down by the kelps. However, we also hypothesized that habitats with lower densities of kelp or during periods of increased wave height would have lower seawater pH and DO due to the reduced influence of E. radiata on these parameters.

Materials and methods

Literature review

We searched the Web of Science and Google Scholar for published and grey literature that contained the following key words (kelp* or seaweed* or “canopy-forming”) and (“seawater chemistry”, “carbon dioxide” or “ocean acidification” or pH). The search was conducted on 10/03/2023 and identified 578 papers which were screened by title and abstract. From the initial screening we included papers that assessed the effects of kelp on seawater chemistry parameters (DIC, DO, HCO3−, pCO2, pH, TA, and Ωarag) and vice versa.

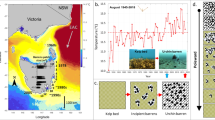

Field measurements

To assess the effects of different habitats and environmental conditions on seawater chemistry, we deployed a suite of loggers and sensors in Williamstown, Port Phillip Bay, Australia (− 37.869, 144.894). Each deployment spanned ~ 10-days. We selected this site because it has areas of intact, moderate, and sparse kelp and barrens near each other (200 m2 and 500 m apart)21. The dominant water motion at this site is driven by wind-generated waves, with very weak influence from tidal currents22. Wave height served as an indicator to evaluate of the effects of hydrodynamics on seawater chemistry in both intact kelp and barrens habitats.

Prior to each deployment, we calibrated the loggers following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Additionally, we assessed the density (m2) and stipe length (cm) of E. radiata inside the intact kelp forest and barrens habitats in both March and September 2021. For the moderate and sparse kelp density habitats, this assessment was conducted in September 2021. The density and stipe length of E. radiata in all habitats was quantified in all habitats using 10 randomly placed 1 m2 quadrats.

The effects of varying densities of E. radiata on seawater pH and DO was assessed by placing 1 logger of each type (Hobo (pH) and Minidot (DO), n = 4 of each) in the centre in each of four habitats (intact kelp, moderate density kelp, sparse density kelp, and barrens) at ~ 3 m depth, in November and December 2021. To determine how the pH and DO inside and outside E. radiata forests (intact kelp forest vs. barrens) varied in response to changes in wave height, 1 logger of each type (Hobo (pH), Minidot (DO), n = 2 of each) was placed in the centre of each habitat at ~ 3 m depth in March, April, November and December 2021 and 1 pressure sensor (RBRsolo3 D | wave 16, n = 2 total) was placed directly in front of each habitat at ~ 5 m depth in March and April 2021.

To test for variation in pH instrument sensitivity, 1 Hobo pH logger and 1 SeaFET V2 Ocean pH sensor were deployed in the centre of the intact E. radiata forest and barrens habitats in March and April 2021. All loggers were deployed for only 10 days to minimize drift in the pH sensors.

Data processing

The absolute pressure values recorded by the RBRs were converted to gauge pressure using atmospheric pressure data from the closest weather station (Williamstown: www.bom.gov.au). The pressure data were then processed to calculated offshore wave heights using the methods detailed by21.

Analyses

We used a one-way ANOVA to test the differences in E. radiata density (ind. m−2) and lamina length (cm) between habitats with different amounts of kelp (fixed, 4 levels = intact, moderate, sparse density kelp, and barrens). We then used two-way ANOVA to test the differences in E. radiata density (ind. m−2) and lamina length (cm) inside and outside the kelp forest (fixed, 2 levels = intact kelp vs. barrens) and through time (fixed, 2 levels = August 2021 and March 2022).

For the seawater chemistry parameters pH and DO, we calculated the daily minimum, maximum, mean and range for each habitat. The effect of kelp density (fixed, 4 levels = intact, moderate, sparse kelp, and barrens), deployment (fixed, 2 levels = November and December) and day nested within deployment (fixed, 10 levels) on these parameters were assessed with generalised linear mixed models. The differences in these parameters inside and outside the kelp forest (fixed, 2 levels = intact kelp vs. barrens), deployment (fixed, 4 levels = March, April, November, and December) and day nested within deployment (fixed, 10 levels) were also tested with generalised linear mixed models.

We combined the March and April 2021 data to test relationships between all offshore wave height (m) and pH and DO values in the intact kelp forest and barrens habitats with quantile regression using the R package quantreg23. Quantile regression was used because of its usefulness in analysing rates of change due to a limiting factor, such as wave height. We performed all quantile regression analyses on the 80th percentile, as changes in the upper percentiles provide a better estimate of the limiting effect of waves on seawater pH and DO compared to changes in the mean. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were then used to assess whether the seawater pH and DO data and the seawater pH recorded by the HOBO and SeaFET sensors were correlated. For all linear models, data were assessed for homoscedasticity and normality using boxplots. The fit of the linear model and generalised linear models were assessed with diagnostics plots. Where these assumptions were not met, boxcox plots were used to suggest an appropriate transformation. When significant differences were found pairwise tests with Tukey’s adjustment were used to explore sources of variation using the library emmeans24. All statistical tests were performed in R (v. 4.3.1)25.

Results

Literature review

Out of 179 studies that met the search criteria, only 16% tested the effects of kelp on various seawater chemistry parameters (i.e. DIC, DO, HCO3−, pCO2, pH, TA, and Ωarag). By contrast, a substantially higher proportion of studies (84%) focused on examining the effects of ocean acidification on kelp.

In total we identified 25 studies that assessed the effect of kelp on seawater chemistry in comparison to controls without kelps, along with an additional 3 studies that quantified the effects of different kelp species and/or habitats on seawater chemistry (see Supplementary Table S1). Most of the studies (88% out of the 25) reported that the presence of kelp led to increases in seawater pH and DO during daylight hours when compared to areas without kelp (Supplementary Table S1). The effects of kelp on seawater chemistry were observed at multiple spatial scales, ranging from within kelp blades to across the entire kelp forest or seaweed farm (Supplementary Table S1).

Among the 25 studies, 15 assessed the effects of kelp forests on seawater pH and DO. These effects exhibited considerable variability with seawater pH increases of 0.01–0.8 units inside vs. outside kelp forests and DO increases of 0.13–2.89 mg/L (1–84%) inside vs. outside kelp forests. Unfortunately, the high variability in study duration and methodological differences, including instrumentation, parameters, and analytical methods, prevented any statistical analyses of this variation (Supplementary Table S1).

A notable finding from these kelp forest studies is the substantial influence of both abiotic (53% of the 15 studies) and/or biotic factors (27% of the 15 studies) in influencing kelp’s capacity to modify seawater chemistry (Table S1). Their findings indicated that the effects of kelps forests on seawater DO and pH differed among kelp species (Supplementary Table S1) although most of the studies concentrated on Macrocystis forests (73% of the 15 studies). Furthermore, the impacts of kelp forests on seawater chemistry tended to increase with density of kelps, showing more pronounced effects during spring and summer, especially in shallower waters and sheltered locations (Supplementary Table S1).

Field measurements

Density and lamina length in different habitats

The density, but not the lamina length, of E. radiata differed significantly between the intact (10.67 m2, 36.52 cm), moderate (6.44 m2, 37.57 cm) and sparse density kelp habitats (0.67 m2, 33.44 cm) and there was no kelp recorded in the barrens habitat (Supplementary Table S2). Through time the density of E. radiata was consistently higher in the intact kelp (March: 12 m2 and September: 10 m2) than the barrens habitat (March: 0 ind per m2 and September: 0 ind per m2) (Supplementary S2). The E. radiata lamina in the intact kelp forest were however shorter in March (29.04 cm) than September (36.52 cm) (Supplementary Table S2).

Seawater chemistry

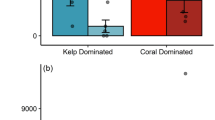

The effects of the habitats on the daily minimum, maximum, mean and range of seawater pH and DO differed among habitats (barrens, and sparse, moderate or intact kelp or barrens vs. intact kelp), deployments and days (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). For all deployments, the post-hoc tests showed the intact kelp habitat had the highest daily maximum and range of seawater pH relative to all the other habitats (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). By contrast, there were no detectable differences in the daily maximum and range of seawater pH between the habitats with moderate and sparse densities of kelp (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). The daily maximum and range of seawater pH was also higher in the habitats with moderate density, but not sparse density, compared to the barrens habitat (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). There were no detectable differences in the daily minimum and mean seawater pH between the intact and moderate density kelp habitats (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). The daily minimum seawater pH and mean seawater pH were lower and higher respectively, in these habitats than the sparse density kelp and barrens habitats (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). There were no detectable differences in the daily minimum seawater pH and mean seawater pH between the sparse density kelp and barrens habitats (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). Across all four deployments, the intact kelp habitat had higher daily maximum and range of seawater pH and lower daily minimum of seawater pH relative to the barrens habitat (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3).

Effects of kelp forest density (Barren: no E. radiata (aqua); K1: sparse density of E. radiata (dark blue), K2: moderate density of E. radiata (green) and Kelp: intact E. radiata forest (yellow)) on seawater pH during the day (white shaded) and night (grey shaded) during the November and December 2021 deployments.

For the daily mean and maximum of seawater DO, the post-hoc tests showed no detectable differences between the intact and moderate density kelp habitats (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig S1). The intact kelp habitat had higher daily mean and maximum DO than the sparse density kelp habitat and the barrens habitat (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig S1). The moderate density kelp but not the sparse density kelp had a higher daily mean and maximum seawater DO than the barrens habitat (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig S1). The intact kelp forest also had lower daily minimum seawater DO than the moderate and sparse density kelp and barrens habitats and the moderate density kelp habitat had lower daily minimum seawater DO than the sparse density kelp habitat but there were no detectable differences in the daily minimum seawater DO between the intact and moderate density kelp habitats and sparse density kelp and barrens habitats (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig S1). The intact and moderate density kelp habitats had higher daily range of DO than the sparse density kelp and barrens habitats (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig S1). Across all four deployments (March, April, November, and December), the intact kelp habitat had higher daily maximum and range and lower daily minimum of seawater DO compared with the barrens habitat but there were no differences in the daily mean of seawater DO in the intact kelp and barrens habitats (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig. S2).

The average significant wave heights recorded during the deployments were comparable between the intact kelp (0.28 m) and barrens habitats (0.27 m). However, the intact kelp habitat (1.95 m) had higher maximum wave heights than the barrens habitat (1.60 m). The results from quantile regression showed significant negative relationships between seawater pH, DO and offshore wave height in the intact kelp (p < 0.001 pH, p < 0.001 DO) but not the barrens habitat (p > 0.05 pH, p > 0.05 DO) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S3).

In all habitats and deployments, the mean hourly seawater pH was positively correlated with the mean hourly DO (Intact kelp: March correlation = 0.84, p < 0.001, April correlation = 0.84, p < 0.001, November correlation = 0.97, p < 0.001 and December correlation = 0.95, p < 0.001, moderate cover kelp: November correlation = 0.90, p < 0.001 and December correlation = 0.86, p < 0.001, sparse cover kelp: November correlation = 0.95, p < 0.001and December correlation = 0.94, p < 0.001, barrens: March correlation = 0.94, p < 0.001, April correlation = 0.70, p < 0.001, November correlation = 0.85, p < 0.001, and December correlation = 0.90, p < 0.001). The mean hourly seawater pH recorded by the HOBO logger (8.10 ± 0.092 and 7.99 ± 0.099; March and April, respectively) was slightly higher than that recorded by the SeaFET (7.92 ± 0.078 and 7.94 ± 0.094; March and April, respectively). However, the analyses showed a strong correlation between instruments across both deployments (correlation = 0.78 and correlation = 0.94, March and April respectively, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

This study combines findings from a literature review with field measurements to assess the effects of kelp forests on seawater chemistry. Our results offer critical insights into some of the abiotic and biotic drivers of temporal variation in kelp forest influence on seawater chemistry. The literature search revealed that kelp forests increase seawater pH and DO levels during the day, relative to areas without kelp, but the effects differ among kelp species and increase with density of kelp and are more pronounced in shallower waters and sheltered locations. Our field measurements were broadly consistent with these observations, with kelp forests significantly altering seawater chemistry, resulting in higher pH and DO levels inside the forests compared to outside. Specifically, the intact E. radiata forest showed higher values for daily maximum (0.11 units and 1.00 mg/L), mean (0.01 units) and range (0.11 units and 2.09 mg/L) but lower minimum pH and DO (− 0.07 units and − 0.97 mg/L) compared to the barrens habitat. Diurnal patterns in seawater pH and DO suggest that the photosynthetic activity of kelp and other seaweeds26 in the intact E. radiata forest and turf algae27 in the barrens habitat play a pivotal role in driving these patterns. These results emphasize the significant role of kelp forests in regulating seawater chemistry and the need for continued research in this area to better understand the impacts of climate change and other stressors on their ecological functions and services (Fig. 5).

Our study findings align with prior research conducted in Tasmania9,19 which also demonstrated positive impact of intact E. radiata forests on local seawater chemistry. Consistent with previous studies9,19 we observed the highest peaks in seawater pH and DO in the late afternoon when the higher light availability (12:00–15:00), warmer seawater temperatures (15:00–20:00) and calm conditions (T. Graham unpublished data) potentially stimulated greater photosynthetic activity and water residence time. The lowest values of seawater pH and DO were recorded in the early morning during the period of highest respiration9,19. However, the daily range in pH and DO for the intact E. radiata forest were consistently positive, suggesting that net photosynthesis outweighs respiration.

Furthermore, our research indicates the effects of kelp forests on seawater chemistry varied among species, which may be linked to their morphology. For instance, studies on Macrocystis pyrifera, a species of kelp that reaches the sea surface, have revealed minimal differences in benthic seawater chemistry inside and outside the kelp forest. However, more pronounced differences in seawater pH and DO within Macrocystis forests have been observed in surface waters where kelp biomass and light availability are greatest10,28. By contrast, shorter taxa such as Ecklonia, Laminaria and Sargassum kelp forests have exhibited significant increases in seawater DO and pH in benthic waters relative to barren areas19,29. These finding highlight that different kelp species may exhibit varying effects on seawater chemistry, emphasizing the important of considering species-specific characteristics and their ecological role in understanding these dynamics.

The impacts of kelp forests on seawater chemistry varied, depending on both kelp density30,31 and local hydrodynamic conditions10,14,16,29. We observed that the intact E. radiata forest had elevated seawater daily maximum seawater pH and DO (0.1 unit and1.00 mg/L) levels compared to habitats with lower densities of kelp and the barrens. Notably, there in the intact E. radiata forest, we identified negative relationships between seawater pH and DO levels and wave heights—the predominant driver of water motion in our study site. Conversely, the same relationships were not observed in the barrens habitat. These findings suggest that fragmented E. radiata forests and barrens characterised by lower density of kelp due to overgrazing by sea urchins26 have a weaker biogeochemical signature owing to the reduced photosynthetic activity32 and decreased water retention time14,33. Hence, the ability of E. radiata forests to buffer OA could be compromised by increasing wave exposure and storminess associated with climate change.

As the impacts of climate change intensify, understanding the role of kelp forests in creating local refuges for associated organisms from OA is increasingly important. Previous research has demonstrated that benthic organisms are particularly sensitive to lower pH conditions34. Negative effects of sustained lower seawater pH have been demonstrated on various taxa including reduced survival of amphipods (pH 7.635), decreased growth rates in molluscs such as juvenile blacklip abalone (pH 6.7936), declined growth rate and gene expression of echinoderms including purple sea urchins (pH 7.637) and diminished calcification rates of calcareous algal taxa like corallines (pH 7.638). All these organisms inhabit the benthos of E. radiata forests32. Our results, therefore, support arguments that intact kelp forests in sheltered locations such as Port Phillip Bay could provide local refuges from OA for certain associated taxa39,40. Nonetheless, the higher variability in seawater pH in intact E. radiata forests might also have adverse implications for the calcification rates of other taxa38.

There is increasing interest in understanding how marine macrophytes such as kelp forests can provide key ecosystems services41. Kelp forests can buffer the impact of OA on key marine taxa including fished species36. At the global scale there is a paucity of data about the conditions in which kelp forests can increase seawater pH and DO. Here we conclude that E. radiata and other kelps can buffer the effects of OA, but the effects are confined to daylight periods42,43,44, calm conditions14,16, and intact forests17,31. Kelp forests include a diversity of species and morphologies45, thus there is a need to understand which species can consistently increase seawater pH and DO, at different spatial and temporal scales, heights in the water column and in what environmental conditions. This will involve collection of more field data across different species, forest characteristics (density, area etc.), water depths and wave exposures. Kelp is one of the dominant habitat-forming organisms of temperate reefs. In many locations, kelp beds are, however, in decline46,47, due to a combination of local and global threats48. A greater understanding of the suite of ecosystem services being lost will underpin more effective management of kelp forests both in Port Phillip Bay and elsewhere.

Data availability

The authors confirm the data supporting the findings of the study are available in the article and its Supplementary material.

References

Doney, S. C. et al. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci.4, 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611 (2012).

IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. (Pörtner, H.-O. et al. Eds.), 8–35 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Cooley, S. R. & Doney, S. C. Anticipating ocean acidification’s economic consequences for commercial fisheries. Environ. Res. Lett.4, 024007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/2/024007/meta (2009).

Guinotte, J. M. & Fabry, V. J. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems. Ann. NY Acad. Sci.1134, 320–342. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1439.013 (2008).

Hall-Spencer, J. M. & Harvey, B. P. Ocean acidification impacts on coastal ecosystem services due to habitat degradation. Emerg. Top. Life Sci.3, 197–206 (2019).

Kapsenberg, L. & Cyronak, T. Ocean acidification refugia in variable environments. Glob Change Biol.25, 3201–3214. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14730 (2019).

Duarte, C. M. Reviews and syntheses: Hidden forests, the role of vegetated coastal habitats in the ocean carbon budget. Biogeosciences14, 301–310 (2017).

Steneck, R. S. et al. Kelp forest ecosystems: Biodiversity, stability, resilience and future. Environ. Con. 29, 436–459 (2002).

Britton, D. et al. Ocean acidification reverses the positive effects of seawater pH fluctuations on growth and photosynthesis of the habitat-forming kelp, Ecklonia radiata. Sci. Rep.6, 26036 (2016).

Hirsh, H. K. et al. Drivers of biogeochemical variability in a central California kelp forest: Implications for local amelioration of ocean acidification. J. Geo Res. Oceans. 1.25, e2020JC016320. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JC016320 (2020).

Kapsenberg, L. & Hofmann, G. E. Ocean pH time-series and drivers of variability along the Northern Channel Islands, California, USA. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 953–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10264 (2016).

Murie, K. A. & Bourdeau, P. E. Fragmented kelp forest canopies retain their ability to alter local seawater chemistry. Sci. Rep.10, 11939 (2020).

Noisette, F. et al. Role of hydrodynamics in shaping chemical habitats and modulating the responses of coastal benthic systems to ocean global change. Glob Change Biol.28, 3812–3829. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16165 (2022).

Traiger, S. B. et al. Limited biogeochemical modification of surface waters by kelp forest canopies: Influence of kelp metabolism and site-specific hydrodynamics. Limnol. Oceanogr.67, 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11999 (2022).

Kregting, L. et al. Safe in my garden: Reduction of mainstream flow and turbulence by macroalgal assemblages and implications for refugia of calcifying organisms from ocean acidification. Front. Mar. Sci.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.693695/full (2021).

Koweek, D. A. et al. A year in the life of a central California kelp forest: Physical and biological insights into biogeochemical variability. Biogeosciences. 14, 31–44 (2017).

Krause-Jensen, D. et al. Macroalgae contribute to nested mosaics of pH variability in a subarctic fjord. Biogeosciences. 12, 4895–4911 (2015).

Pfister, C. A. et al. Kelp beds and their local effects on seawater chemistry, productivity, and microbial communities. Ecology. 100, e02798. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2798 (2019).

Ling, S. D. et al. Remnant kelp bed refugia and future phase-shifts under ocean acidification. PloS One. 15, e0239136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239136 (2020).

Li, H. et al. The diel and seasonal heterogeneity of carbonate chemistry and dissolved oxygen in three types of macroalgal habitats. Front. Mar. Sci.9, 857153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.857153/full (2022).

Morris, R. L. et al. Kelp beds as coastal protection: Wave attenuation of Ecklonia radiata in a shallow coastal bay. Ann. Bot.125, 235–246 (2020).

Tran, H. Q. et al. Hydrodynamic climate of Port Phillip Bay. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.9(8), 898 (2021).

Koenker, R. et al. Package ‘quantreg’. Reference manual available at R-CRAN. (2018). https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/quantreg/quantreg.pdf

Lenth, R. et al. Package ‘emmeans’. (2019). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/emmeans.pdf

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2021). https://www.R-project.org/

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Canopy macroalgae influence understorey corallines’ metabolic control of near-surface pH and oxygen concentration. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser.525, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps11190 (2015).

Reeves, S. E. et al. Kelp habitat fragmentation reduces resistance to overgrazing, invasion and collapse to turf dominance. J. App Ecol.59, 1619–1631. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14171 (2022).

Frieder, C. et al. High temporal and spatial variability of dissolved oxygen and pH in a nearshore California kelp forest. Biogeosciences. 9, 3917–3930 (2012).

Pfister, C. A. et al. Kelp beds and their local effects on seawater chemistry, productivity, and microbial communities. Ecology. 100(10), e02798. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2798 (2019).

Krause-Jensen, D. et al. Macroalgae contribute to nested mosaics of pH variability in a subarctic fjord. Biogeosciences. 12(16), 4895–4911 (2015).

Wahl, M. et al. Macroalgae may mitigate ocean acidification effects on mussel calcification by increasing pH and its fluctuations. Limnol. Oceanogr.63(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10608 (2018).

Wernberg, T. et al. Biology and ecology of the globally significant kelp Ecklonia radiata. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol.57, 265–324 (2019).

Elsmore, K. et al. Wave damping by giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera. Ann. Bot.https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcad094/7226144 (2023).

Donham, E. M. et al. Coupled changes in pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen impact the physiology and ecology of herbivorous kelp forest grazers. Glob. Change Biol.28, 3023–3039. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16125 (2022).

Poore, A. G. et al. Effects of ocean warming and lowered pH on algal growth and palatability to a grazing gastropod. Mar. Biol.163, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-016-2878-y (2016).

Burke, C. et al. Environmental requirements of abalone. FRDC Project no 97/323 School of Aquaculture, University of Tasmania, Australia. (2001). https://www.frdc.com.au/sites/default/files/products/1997-323-DLD.pdf

Devens, H. R. et al. Ocean acidification induces distinct transcriptomic responses across life history stages of the sea urchin Heliocidaris Erythrogramma. Mol. Ecol.29, 4618–4636. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15664 (2020).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Diurnal fluctuations in seawater pH influence the response of a calcifying macroalga to ocean acidification. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. Ser. B. 280, 20132201. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2201

Hurd, C. L. Slow-flow habitats as refugia for coastal calcifiers from ocean acidification. J. Phycol.51, 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12307 (2015).

Noisette, F. & Hurd, C. Abiotic and biotic interactions in the diffusive boundary layer of kelp blades create a potential refuge from ocean acidification. Func Ecol.32, 1329–1342. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13067 (2018).

Eger, A. M. et al. The value of ecosystem services in global marine kelp forests. Nat. Comm.14, 1894 (2023).

Delille, B. et al. Influence of subantarctic Macrocystis bed metabolism in diel changes of marine bacterioplankton and CO2 fluxes. J. Plank Res.19(9), 1251–1264 (1997).

Delille, B. et al. Seasonal changes of pCO2 over a subantarctic Macrocystis kelp bed. Pol. Biol.23, 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003000000142 (2000).

Delille, B. et al. Influence of giant kelp beds (Macrocystis pyrifera) on diel cycles of pCO2 and DIC in the Sub-antarctic coastal area. Est. Coast Shelf Sci.81(1), 114–122 (2009).

Dayton, P. K. Ecology of kelp communities. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 16, 215–245. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.001243 (1985).

Krumhansl, K. A. et al. Global patterns of kelp forest change over the past half-century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 13785–13790 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606102113

Wernberg, T. et al. Chapter 3—Status and trends for the world’s kelp forests. World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition): Volume III: Ecological Issues and Environmental Impacts, 57–78. (Elsevier, 2019). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128050521000036

Strain, E. M. et al. Identifying the interacting roles of stressors in driving the global loss of canopy-forming to mat‐forming algae in marine ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol.20, 3300–3312. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12619 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Dean Chamberlain provided invaluable assistance in the field. This work was supported by the Australian Academy of Science Thomas Davis Grant awarded to ES and the National Centre for Coasts and Climate, funded through The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA collected field data. ES analysed the data. ES, SS and RM designed the study. ES wrote the original draft, with subsequent contributions by other authors. KN provided advice on methods and access to loggers and sensors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strain, E.M.A., Swearer, S.E., Ambler, I. et al. Assessing the role of natural kelp forests in modifying seawater chemistry. Sci Rep 14, 22386 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72801-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72801-5