Abstract

The digital elevation model (DEM) provides important data support for 3D terrain modeling. However, due to the complex and changeable terrain in the real world and the high cost of field measurement, it is extremely difficult to obtain continuous and high-density elevation data directly. Therefore, it is necessary to rely on spatial interpolation technology to restore the DEM overall picture in the original sampling area. The traditional spatial interpolation method usually has the characteristics of low model complexity and high computational cost, which leads to low real-time performance and low precision of the interpolation process. The interpolation operation based on DEM data can be considered as a special image generation process where the input is a DEM image with missing values and the output is a complete DEM image. At present, a large number of studies have proved that deep learning methods are very effective in image generation tasks. However, the training of deep learning models requires the support of a large number of high-quality data sets. DEM data in various countries, especially in key regions, are usually restricted by privacy protection regulations and cannot be disclosed. The emergence of Federated Learning (FL) provides a new solution, which supports local training on multiple end nodes, without sending local data to a remote center server for centralized training, effectively protecting data privacy. In this study, we propose a DEM interpolation model based on FL and multiScale U-Net. The experimental results show that compared with the traditional method, this model has faster processing speed and lower interpolation precision. At the same time, this research result provides a new way for efficient and secure use of terrain information, especially in those application scenarios that have strict requirements for DEM data privacy and security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DEM is the three-dimensional model that uses a series of elevation points to represent the terrain of the earth surface. It stores the height value of the terrain in the form of a grid, and can reflect the fluctuation state of the surface in detail and accurately. This kind of data not only contains the basic morphology of mountains and valleys, but also can show the subtle changes of plains, hills and other terrain, which is an important data for analyzing and understanding surface characteristics. DEM can also provide vital topographic data reference for large-scale engineering construction, earth science and safe navigation. For example, tasks in practical applications such as cross-sea bridge construction, oil and gas resource exploration, deep-sea sediment migration pattern research, earth plate dynamics research, and water and underwater traffic safety assurance rely on accurate topographic data as support1,2,3,4,5.

Marine Geographic Information System (MGIS)6, as a new Marine information management technology, has the advantages of high data integration, strong analysis ability and good visualization effect. It can realize multiple functions such as Marine environment monitoring, Marine resource management and Marine scientific research, and is an important Marine information infrastructure. In recent years, with the increasing demand for Marine resources development and environmental protection, MGIS has been widely used and developed rapidly in the world. Marine geospatial information technology service software based on electronic chart is a comprehensive service technology that integrates MGIS technology, remote sensing technology, oceanography and computer science. It mainly relies on the standard electronic chart (ENC)7 file for the storage, management and display of Marine spatial geographic distribution data to support the needs of Marine resources development, Marine environment monitoring, maritime navigation safety and Marine scientific research and other fields.

At present, most of the existing electronic chart systems in the market are mainly two-dimensional map display, because the three-dimensional terrain display of electronic chart depends on high resolution and high precision DEM data. DEM data in ENC file is mainly stored in the form of bathymetry layer. However, due to the limitation of sampling cost and accuracy, the depth information of bathymetry often has the problem of missing sampling points and low resolution. In order to reconstruct the full depth information of the sampling area, we need to rely on the spatial interpolation algorithm. Traditional spatial interpolation methods such as inverse distance weighted interpolation (IDW)8 and Kriging interpolation9 usually have low model complexity and require a lot of iterative computation to approximate interpolation points. This often results in significant errors and lower real-time in the generated depth data. At the same time, DEM data in key areas are usually sensitive information and generally will not be made public. Traditional privacy protection algorithms are often ineffective in protecting such data. In order to effectively protect data privacy, we need to study a privacy protection mechanism for discrete elevation sampling points spatial interpolation algorithm to solve the above problems.

In the rapid development of the field of image processing, deep learning methods10,11,12,13,14,15 have emerged in recent years, especially in image enhancement, image restoration and image generation, showing significant advantages. It is especially worth mentioning that the invention of convolutional neural network (CNN)16,17 has brought a new idea for spatial interpolation technology, which can extract the hidden deep information in the image by using the unique convolutional layer, and achieve good results in the image cavity completion task. Spatial interpolation is a kind of void completion task, which is based on finite discrete measurement points and realizes the accurate mapping of global space by learning the interrelation between these points. For example, Iizuka et al.18 built a generative adversarial network with a dual discriminator structure to enhance the stability of the network while ensuring the global consistency of the completion region. Liu et al.19 use partial convolutions to segment the invalid parts of the feature graph and transfer them to the next layer of the network to form an irregular mask, thereby improving the accuracy of the completion region. Donget al.20 proposes a framework of conditional generation adversarism networks. Combined with L1 norm loss function, remarkable filling effect has been achieved on Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), a global standard DEM dataset.

In this study, we evaluate and study U-Net network based on multi-scale modules and conduct spatial interpolation studies of discrete elevation points using a FL framework21,22,23. The experimental phase was trained and tested using the open source global terrain model dataset ETOPO 2022, which provides 15 arcseconds ((approx. 500 m at the equator) resolution elevation data covering the world’s oceans and land. Our goal is to highlight the advantages of FL and deep learning networks in the task heavy interpolation of discrete elevation point Spaces, especially in protecting user data security and confidential execution. And, the main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A DEM interpolation task based on FL framework is designed, which effectively protects the privacy and security of local data.

-

2.

The client is randomly selected for training, and the number of local iterations for each client is increased, which effectively reduces the number of communications.

-

3.

The DEM interpolation task is innovatively transformed into the learning task of the deep learning model, and the accurate interpolation reconstruction can be carried out without any prior knowledge through the trained network.

-

4.

The designed U-Net network with multi-scale module can complete the interpolation task well, and has the advantages of fast interpolation speed and high interpolation precision compared with the traditional method.

Ralated works

Spatial interpolation

Spatial interpolation can be considered as a special kind of image restoration process, whose input is finite and discrete measurement points, and the purpose is to output an accurate map of the global space by learning the cross-correlation between the existing measurement points. Deep learning methods are widely used in natural language processing and image generation. In recent years, CNN-based models have been used more and more widely, especially in the field of images. Therefore, it is necessary to extend the CNN model to overcome the differences between CNN and spatial interpolation tasks in order to achieve accurate global estimation of the sampled data in a given space.

Zhu et al.24 combined the idea of conditional generative adversarial networks to transform spatial interpolation tasks into conditional generative adversarial tasks, and designed a new spatial interpolation deep learning architecture called conditional encoder-decoder generative adversarial neural networks. The network combines adversarial learning model with encoder-decoder structure to capture the similarity between deep expression and local structure in geospatial data, and provides a new solution for spatial interpolation of land terrain DEM data. Zhang et al.25, proposed a deep generation model, which uses the generation of reconstruction loss and anti-network loss to assist network training, and realizes fine reconstruction of images in the DEM filling space task. For an ocean-related interpolation task, Hirahara et al.26 designed a sea surface temperature (SST) image-mapping algorithm to estimate the error value of SST (i.e. the difference between SST and mean SST). In this algorithm, the cloud-free mean SST is used as a preliminary estimate of SST. Then, the cloud free SST image is reconstructed by using the anomaly mapping network to complete the mapping of SST in the missing region.

The quality of a deep learning model depends largely on whether the data used for training is sufficient and good enough. However, because high-precision DEM data is generally limited by security problems, we need to develop a joint learning framework to solve the problem that local data cannot be uploaded to the central server for training.

Federated learning

In 2016, FL was proposed as a new distributed machine learning training method. The core goal is to train the same model with devices scattered across different geographic locations, while ensuring effective privacy protection for local data. This approach is significantly different from traditional centralized machine learning training methods and parallel computing methods. The latter focuses on optimizing machine learning computational efficiency by taking advantage of the parallel computing advantages of multiple processors on centralized data sets. While existing machine learning technologies demonstrate strong performance, they face data privacy challenges. Because these technologies often require training data to be sent to a central server, this process can lead to data security issues when data is captured and shared27,28.

The architecture of FL follows a typical master-slave configuration, as shown in Fig. 1. In a FL framework, each independent actor (or device) trains its own local model individually using the private data it has. These devices then send updates of their own local model to a central server, which uses aggregation algorithms to consolidate all local updates to update the global model. Finally, the local actor downloads global updates from the central server to update the local model and repeats the process until the model converges. Based on local training data, FL can be subdivided into three main types: horizontal FL, vertical FL, and transfer FL. In order to ensure that the local data security and privacy, the researchers have been put forward for the polymerization technology, many algorithms29,30,31. For example, the earliest FeadSDG algorithm32 performed a single batch gradient calculation by randomly selecting a subset of clients in each round of communication. Then, in order to improve the efficiency of communication, the researchers proposed the FedAVG algorithm. Unlike FeadSDG, it allows the local client to perform multiple rounds of iterative training locally before returning the gradient calculation results to the central server. Therefore, FeadSDG algorithm greatly saves the communication time.

Meanwhile, it has been shown that sharing raw local updates compromises users’ privacy33,34,35. The existing differential privacy technologies in FL can be roughly divided into two categories: curator model (DP) and local model (LDP). Dp-based FL can achieve higher learning accuracy, but relies on a trusted analyzer to collect the original updates of the local endpoint. For example, McMahan et al.36 added a user-level differential privacy protection mechanism to the FegAvg framework to achieve effective protection of local user data without basically losing prediction accuracy. Geyer et al.37 proposed a federal optimization algorithm for client differential privacy protection, and analyzed and concluded that a model can be trained to meet the accuracy when the number of clients is sufficient. Ldp-based FL encrypts local updates before they are sent to the remote end to ensure that the privacy of local updates is not disclosed, but it is limited by the computing power of the local end. For example, Wang et al.38 proposed an \({\epsilon }\)-local differential privacy algorithm, which effectively protects the private information of local users and aggregate analyzers from being leaked. Liu et al.39 proposed a two-stage framework for federal SGD under LDP to alleviate dimension dependency problems, and verified its effectiveness through a large number of experiments.

Methodology

Problem statement

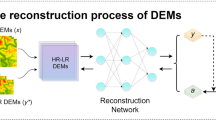

The spatial interpolation task based on discrete sampling DEM is completed by the interpolation network under the FL framework. The input of the network is the DEM image after random sampling, and the output is the complete DEM image, so that the network is expected to learn the relevant knowledge of spatial interpolation after training.

Suppose we denote the data domain as \(\mathcal {V} \triangleq \mathbb {R}^{C \times W \times H }\), with W and H signifying the spatial breadth and height dimensions, respectively, of the input DEM image, and C indicating the quantity of color channels embedded within the data; for monochromatic images, this count is unity, but for RGB images, it triples to three. The unprocessed DEM information can be embodied as an element x within \(\mathcal {V}\). Further, given that the training dataset x adheres to a particular sampling scheme expressed as \(f^* = \big [(c_1, r_1), (c_2, r_2), ..., (c_m, r_m)\big ] \in \mathbb {R}^{2m}\), wherein \((c_k, r_k)\) pinpoints the positional coordinates of the k-th sampled datum, the depiction of the image post-sampling proceeds can be represented as follows.

The key of this task is to make the model learn the ability of spatial interpolation through training process and to ensure the security of local user data. Therefore, we innovatively design a spatial interpolation model architecture based on FL to solve the spatial interpolation problem of random discrete sampling DEM data.

Federated learning framework

Federated learning is a distributed machine learning framework in which multiple local users can jointly train a more Ruben global model without sharing private data. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the deployed FL framework. The framework consists of five core steps. Step 1, the initialization operation, involves initializing the model on the central server and delivering the model to the default client. The second step is local training, in this process, each client uses the received model, combined with their own private DEM data for localized training. Next comes Step 3, the parameter transfer phase, where each client model update is transmitted to the central server for processing after the client training is completed. This is followed by Step 4, the model aggregation phase, in which the central server uses specific aggregation algorithms to aggregate model updates from each client to generate an optimized global model. Finally, Step 5, the global model sharing and evaluation phase, distributes the trained global model to all clients and evaluates it on the test data set.

The SCAFFOLD algorithm proposed in 2020 is an improvement on FedAvg and can solve the problem of non-independent co-distribution and client-drift of local data. During the system’s training, a “control variate” c is introduced to adjust the training direction. Every time the client iteratively updates the model, this control variable is also updated synchronously to ensure the accuracy of the training process. At the same time, the algorithm can effectively reduce the degradation of training results caused by the difference of multiple local private data and the imbalance of distribution. Therefore, we choose the SCAFFOLD algorithm to build a FL framework. And, the implementation of the SCAFFOLD algorithm consists of three core stages: First, the client model is updated locally (Step 3); Next, perform the appropriate local update for the client’s control variables (Step 4); Finally, do a summary update (Step 5). Algorithm 1 describes the above steps in detail.

Spatial interpolation model

MultiScale U-Net

The U-Net structure was originally used for medical image segmentation tasks. Because of its excellent performance, it has been applied in many fields in recent years. As shown in Fig. 3, it consists of two paths. The path on the left is an encoder consisting of a shrink path for feature extraction. The correct path is a decoder consisting of an extended path that is used to reconstruct the interpolated image from the features.

According to one research paper40, the addition of a batch normalization layer can make the network difficult to train and even cause the network to diverge on image generation tasks. Therefore, we mainly use convolutional layers to construct our network, which is defined as follows:

where, \(k_i\) denotes the convolution kernel, \(x_{l-1}\) signifies the preceding layer’s output feature map. The bias term \(b_i\) is also incorporated, and the resultant z represents the feature map following the convolutional layer’s transformation. The nonlinear activation function \(f(\cdot )\), as specified in equation (3), augments the network’s representational prowess by introducing distortions or transformations to the input, thus empowering the network to capture intricate features. For the purpose of this study, the ReLU function is chosen to expedite the convergence of the network’s training procedure.

In light of the intricate nature of geographic spatial data features encountered in spatial interpolation tasks, we have introduced modifications to the U-Net architecture by integrating multi-scale convolution modules, thereby naming it the Multi-Scale U-Net, as show in Fig. 4. The input data flows through four parallel processing branches, each employing distinct kernel sizes, and the outputs from these branches are subsequently fused.

Joint loss

In order to improve the generation ability and interpolation accuracy of the model, we use a joint loss to train the network, including a reconstruction loss and a perception loss. Each loss function is targeted at a different Angle of generating the graph, that is, each loss function corresponds to a specific subtask. Since the fundamental purpose of these two losses is to strengthen the similarity between the generated image and the original unsampled image, they can share the same network structure without adding new branches. And, the total joint loss function is defined as follows:

where, \(l_{\text{ con }}\) and \(l_{\text{ pec }}\) correspond to content loss and perception loss respectively, and \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) are the weight coefficients of the two kinds of losses.

Content loss: The measure of content loss refers to the loss of pixels at matching position between the authentic training image \(\pmb {x}^{(i)}\) and the fake image \(G\left( f\left( \pmb {x}^{(i)}\right) \right)\) which is generated by the network via extraction from transformed data \(f\left( \pmb {x}^{(i)}\right)\).

In 2017, Ledig et al.41 employed the the loss function of mean squared error (L2), attaining high scores in quantitative evaluations. However, this approach often leads to overly smooth textures in the generated imagery, conveying a blurred appearance. Zhao et al.42 observed that models trained with the Manhattan distance loss (L1) exhibited superior performance and faster convergence rates through extensive experimentation. Therefore, we utilize L1 loss as our content loss function, and its formulation is detailed as follows:

where, W and H represent the width and height of input image.

Perceptual loss: Perception loss focuses more on capturing the high-level semantic differences between the images, while content loss focuses on measuring the difference between the corresponding pixel positions in the image. For example, let’s say we have two extremely similar images A and B, where B is an offset image with A horizontally shifted by one pixel. Although the two images are visually very close, content loss may give a larger error, while perception loss may show a smaller error. The specific form of the perceived loss function is as follows:

where, \(\varphi (\cdot )\) serves as the function responsible for the extraction of high-level semantic features. As the network’s architecture deepens, the nature of the extracted features shifts from fundamental to increasingly sophisticated and high-level representations. Recognizing the proficiency of pre-trained image classification networks in feature extraction, our study leverages the pre-trained VGG19 network to procure high-level semantic features from input images. Additionally, to ensure a comprehensive capture of multi-scale features within the images, we opt to integrate the outcomes of the VGG19 network’s initial 13 layers, thereby establishing the basis for our final perceptual loss calculation.

Experiment

Dataset

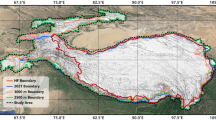

Our experimental data comes from the ETOPO 2022 Global Relief Model, a dataset of authoritative global terrain models. The dataset covers the world’s oceans and lands, providing elevation information accurate to a resolution of 15 arcseconds (approx. 500 m at the equator). To simulate FL framework built with multiple local clients, we selected data from nine different locations around the world and cropped the collected data to a uniform \(64\times 64\) pixel size for the consideration of computational efficiency. Among them, the data from 8 locations are used as training sets and verification sets for network training, and the data collected from another location is used as test sets for network testing. Each region had 3136 pieces of data, 80% of which were used for training and the remaining 20% for validation.

In the training process, in order to ensure that the model can learn the comprehensiveness and diversity of terrain features without requiring too much sampling information, we adopted a random sampling method and randomly selected 1200 pixels from each \(64\times 64\) DEM data. The randomly sampled data is used as the spatial interpolation task of the input discrete DEM data of the interpolation network, as shown in the Fig. 5. The elevation is indicated by different shades of color, with the darker color representing the lower altitude and the corresponding lighter color representing the higher altitude. For the unsampled points in the randomly sampled image, that is, the region with pixel value 0, we mark them with blue color blocks.

Experimental setup

The experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu system server equipped with an Intel®Xeon®Silver 4214R@2.40GHz CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 3080Ti 12GB graphics card. We used Python 3.8.10 and the Pytorch deep learning framework to build our model, as well as the cuDNN 8.1.0 and CUDA 12.2 toolkit, enabling the utilization of GPUs for enhanced deep learning capabilities. We configured the framework and model according to the hyperparameters listed in Table 1, and initialized the initial weights of each node in the neural network with Gaussian distribution.

In the training phase, we use the Adam optimizer. In total, we collected DEM data from 9 different regions in the world, and the pixel size is \(64 \times 64\) gray iamge. Eight of these regions represent eight clients for training and validation, and one for testing. And the global training runs a total of 50 epochs.

Performance evaluation metrics

In order to accurately measure the effect of reconstruction, we used four key evaluation indexes: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index (SSIM), which together constitute the benchmark for evaluating the accuracy of reconstructed images. Specifically, MAE and RMSE measure the overall deviation of pixels or feature values in an image by calculating the average difference between the predicted value and the true value. PSNR focuses on comparing the peak signal-to-noise ratio of the reconstructed image with the original image, so as to show the sharpness and detail retention of the image. SSIM, on the other hand, focuses on comparing the structural information of two images to assess the similarity between them, including the similarity between the reconstructed image and the reference image. And, the specific definitions of these indicators are described below.

where, m represents the pixel count within the input image; \(\textbf{y}_{\text {true}}\) and \(\textbf{y}'\) denote the pixel intensities of the authentic and interpolated images, respectively; \(MAX_I\) signifies the utmost color intensity achievable for any image pixel. Constants \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are incorporated to avert division by zero scenarios, while \(\mu\), \(\sigma ^2\), and \(\sigma _{y y\prime}\) symbolize the mean, variance, and covariance, respectively. Notably, a diminution in Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Peak-to-Mean Square Error (PMSE) values is indicative of an enhancement in the interpolative quality of the image. Conversely, heightened values of Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) are synonymous with superior outcomes in image interpolation tasks.

Training

After 60 global epochs, we get a MultiScale U-Net model that can be used for global discrete DEM interpolation. The change of training loss curve with training eopch is shown in Fig. 6. It can be clearly observed from the figure that with the increase of training rounds, the interpolation loss of our model gradually decreases and enters a relatively stable interval after reaching 30 global epoches. In the end, the MultiScale U-Net model stabilized at about 0.329. This performance means that with the deepening of the training process, the spatial interpolation ability of the model is significantly improved, and the stable performance is finally achieved.

By observing the training curve, we can understand the dynamic change of the model during the training process and its generalization ability for unknown data. As the number of training rounds increases, the interpolation loss of our model decreases gradually. After reaching 30 global epochs, it enters a relatively stable interval, that is, the loss curve of training and verification remains stable at about 0.1 in the late training period, which clearly indicates that the model performance has reached a certain convergence. This stability not only reveals that the model has successfully captured the underlying pattern of the data, but also indicates that the model is close to the performance saturation point, and the improvement that further training can bring is relatively limited. Another notable feature is that the training loss curve has been consistently lower than the verification loss curve since the fifth training cycle and maintains this trend throughout the subsequent training. Although this may indicate a slight overfitting, that is, an over-adaptation to the training data, the small gap between the two indicates that this overfitting is not significant.

Evaluation

In order to verify that our model has the ability to perform spatial interpolation on discretely sampled DEM data after training, we use the saved intermediate process model in the iterative process to test on the validation set. Specifically, we use the test set data and randomly select 1200 sampling points for each DEM image as interpolation data points. Further, we calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) between the false data generated by model interpolation and the real data, and plot the corresponding interpolation error curve, as shown in Fig. 7a. In addition, we also draw a box plot reflecting the interpolation error distribution of all pixels, as shown in Fig. 7b.

It can be observed from Fig. 7a that with the progress of training, the interpolation error of DEM shows an obvious downward trend at the initial stage, and gradually becomes stable after about 30 global iterations.When the network attains a stable state, the interpolation error approximates \(\varepsilon \approx\) 90 m, which is deemed acceptable given the range of terrain elevations between − 7 and 6999 m. This is also verified by the box plot in Fig. 7b, which clearly shows that as training progresses, the average error decreases and the error distribution becomes more concentrated.

Discussion and analysis

Assessing the infuence of client participation

To evaluate the impact of the number of clients in the FL framework on training results, we analyzed the scenarios with 2, 4, 6, and 8 participating clients. Meanwhile, we chosed the most common federal learning algorithm FedAVG and FedSGD for comparison. The number of global training rounds for all algorithms is 50 epochs, and the experimental results are shown in Fig. 8. It can be seen from the figure, as the number of clients increases, the loss of the model gradually decreases. This result is due to the increase in trainable data set due to the increase in the number of clients. The SCAFFOLD based model is also the smallest, which further demonstrates its support for non-independent, uniformly distributed data.

The SCAFFOLD algorithm selects a random percentage of clients for a shorter communication time than if all clients were selected. In addition, we compared with FedSGD and FedAVG algorithms in terms of calculation time and cost, and the detailed calculation resuqlts are shown in Table 2.

Compared with traditional methods

Figure 9 shows the comparison of interpolated images obtained by different interpolation methods. From a visual point of view, compared with the classical Krigining and IDW methods, our model shows better resolution and closer similarity to the original image in the interpolated image. This significant improvement indicates that our model can successfully learn complex geographic feature knowledge contained in DEM data after joint training of FL, and has the ability to perform accurate spatial interpolation from discrete DEM data.

Meanwhile, we also quantitatively compare and evaluate our model with the traditional spatial interpolation method on the test set data, and the relevant data are summarized in Table 3. As shown in the table, our model achieved the lowest values in both MAE and PMSE indexes, which were 90.4 and 158.2 respectively. In particular, compared with the Kriging method, this model achieves a 29.4% and 25.0% improvement on MAE and PMSE, respectively. Not only that, our model also achieved the best performance in both PSNR and SSIM evaluations. This result fully proves that this model can provide high quality and high visual effect interpolated image output while reducing the interpolation error. Moreover, Compared with the previous methods, the proposed method greatly improves the speed of DEM spatial interpolation. The average time consuming is 0.046s, which is only 8.9% of the Kriging method.

Conclusion

Machine learning technology, especially deep learning technology based on convolutional neural network, is developing in the field of image generation. In this study, we innovatively transform a discrete DEM based interpolation task into an image generation task and explore the potential and applicability of FL in this context. Our proposed DEM interpolation framework based on FL and MultiScale U-Net networks is a new paradigm, and although it shows significant advantages in the security and confidentiality of private data, there is little research in this area. The experimental results show that compared with the traditional interpolation methods IDW and Kriging, our method has stronger feature capturing ability and lower interpolation error in DEM spatial interpolation tasks. In addition, the federal learning framework is used to enable users to work cooperatively on discrete DEM spatial interpolation, while keeping the data private. In addition to focusing on the performance of the model itself, the actual deployment must also take into account the needs of efficiency and hardware configuration, which is particularly important in resource-constrained regions. We select three federative learning strategies for training discrete DEM interpolation tasks, and analyze their efficiency and accuracy. The results show that the FL framework based on SCAFFOLD has lower communication time and higher interpolation accuracy. In conclusion, this study lays a foundation for the task of training discrete DEM spatial interpolation models based on multi-user collaboration, and provides a strong support for in-depth understanding of the interaction between global gravity field and terrain, exploring the diversity of land balance mechanisms and the impact of terrain on ocean flow patterns.

Data availability

The experimental phase was trained and tested using the open source global terrain model dataset ETOPO 2022, which unfortunately we cannot provide due to copyright issues. But the data set can be obtained at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/etopo-global-relief-mode. Meanwhile, because this paper is jointly completed with the support of the two universities, and based on the requirements of the cooperation between the two universities, the data generated and analyzed in the current research process are not publicly available. But the source code can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yin, H. et al. Land scale division and multifunctional evaluation for Fuping county, China, based on dem-based watershed analysis. Sci. Rep.14, 11384 (2024).

Jiang, J. et al. Study of slope length (l) extraction based on slope streamline and the comparison of method results. Sci. Rep.14, 6047 (2024).

Sun, Q. & Li, J. A method for extracting small water bodies based on dem and remote sensing images. Sci. Rep.14, 760 (2024).

Xi, M. et al. Inspection path planning of complex surface based on one-step inverse approach and curvature-oriented point distribution. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas.71, 1–11 (2022).

Fontanelli, D., Moro, F., Rizano, T. & Palopoli, L. Vision-based robust path reconstruction for robot control. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas.63, 826–837 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. Selection of mariculture sites based on ecological Zoning-Nantong, China. Aquaculture578, 740039 (2024).

Hsieh, M.-H., Xia, Z. & Chen, C.-H. Human-centred design and evaluation to enhance safety of maritime systems: A systematic review. Ocean Eng.307, 118200 (2024).

Shepard, D. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data. In Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference, 517–524 (1968).

Reuter, H. I., Nelson, A. & Jarvis, A. An evaluation of void-filling interpolation methods for SRTM data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci.21, 983–1008 (2007).

Al-lQubaydhi, N. et al. Deep learning for unmanned aerial vehicles detection: A review. Comput. Sci. Rev.51, 100614 (2024).

Nazir, M. B. et al. Charting new frontiers: Ai, machine learning, and deep learning in brain and heart health. Revista Espanola de Documentacion Cientifica18, 209–237 (2024).

Yang, J., Cheng, C., Xiao, S., Lan, G. & Wen, J. High fidelity face-swapping with style convtransformer and latent space selection. IEEE Trans. Multimedia26, 3604–3615. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2023.3313256 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Efficient data-driven behavior identification based on vision transformers for human activity understanding. Neurocomputing530, 104–115 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Say no to redundant information: Unsupervised redundant feature elimination for active learning. IEEE Trans. Multimedia26, 7721–7733 (2024).

Xi, M. et al. A lightweight reinforcement-learning-based real-time path-planning method for unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J.11, 21061–21071 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. A review of convolutional neural networks in computer vision. Artif. Intell. Rev.57, 99 (2024).

Zhao, L. & Zhang, Z. A improved pooling method for convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep.14, 1589 (2024).

Iizuka, S., Simo-Serra, E. & Ishikawa, H. Globally and locally consistent image completion. ACM Trans. Graph.36, 1–14 (2017).

Liu, G. et al. Image inpainting for irregular holes using partial convolutions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 85–100 (2018).

Dong, G., Chen, F. & Ren, P. Filling SRTM void data via conditional adversarial networks. In IGARSS 2018-2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 7441–7443 (IEEE, 2018).

Ren, Y., Cao, Y., Ye, C. & Cheng, X. Two-layer accumulated quantized compression for communication-efficient federated learning: Tlaqc. Sci. Rep.13, 11658 (2023).

Ahmed Khan, H., Naqvi, S. S., Alharbi, A. A., Alotaibi, S. & Alkhathami, M. Enhancing trash classification in smart cities using federated deep learning. Sci. Rep.14, 11816 (2024).

Mamba Kabala, D., Hafiane, A., Bobelin, L. & Canals, R. Image-based crop disease detection with federated learning. Sci. Rep.13, 19220 (2023).

Zhu, D. et al. Spatial interpolation using conditional generative adversarial neural networks. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci.34, 735–758 (2020).

Zhang, C., Shi, S., Ge, Y., Liu, H. & Cui, W. Dem. void filling based on context attention generation model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf.9, 734 (2020).

Hirahara, N., Sonogashira, M. & Iiyama, M. Cloud-free sea-surface-temperature image reconstruction from anomaly inpainting network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens.60, 1–11 (2021).

Kaissis, G. A., Makowski, M. R., Rückert, D. & Braren, R. F. Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nat. Mach. Intell.2, 305–311 (2020).

Li, T., Sahu, A. K., Talwalkar, A. & Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag.37, 50–60 (2020).

Bonawitz, K. et al. Practical secure aggregation for federated learning on user-held data. arXiv preprintarXiv:1611.04482 (2016).

Lian, X. et al. Can decentralized algorithms outperform centralized algorithms? a case study for decentralized parallel stochastic gradient descent. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.30 (2017).

Li, T. et al. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst.2, 429–450 (2020).

McMahan, B., Moore, E., Ramage, D., Hampson, S. & y Arcas, B. A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 1273–1282 (PMLR, 2017).

Nasr, M., Shokri, R. & Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive privacy analysis of deep learning: Passive and active white-box inference attacks against centralized and federated learning. In 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 739–753 (IEEE, 2019).

Hitaj, B., Ateniese, G. & Perez-Cruz, F. Deep models under the gan: Information leakage from collaborative deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 603–618 (2017).

Zhu, L., Liu, Z. & Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.32 (2019).

McMahan, H. B., Ramage, D., Talwar, K. & Zhang, L. Learning differentially private recurrent language models. arXiv preprintarXiv:1710.06963 (2017).

Geyer, R. C., Klein, T. & Nabi, M. Differentially private federated learning: A client level perspective. arXiv preprintarXiv:1712.07557 (2017).

Wang, N. et al. Collecting and analyzing multidimensional data with local differential privacy. In 2019 IEEE 35th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 638–649 (IEEE, 2019).

Liu, R., Cao, Y., Yoshikawa, M. & Chen, H. Fedsel: Federated sgd under local differential privacy with top-k dimension selection. In Database Systems for Advanced Applications: 25th International Conference, DASFAA 2020, Jeju, South Korea, September 24–27, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 25, 485–501 (Springer, 2020).

Lim, B., Son, S., Kim, H., Nah, S. & Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 136–144 (2017).

Ledig, C. et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4681–4690 (2017).

Zhao, H., Gallo, O., Frosio, I. & Kautz, J. Loss functions for neural networks for image processing. Comput. Sci. (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62271345, 62306211, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2023M742608, and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF GZC20231919.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the research: Ziqiang Huo, Jiabao Wen. Acquisition of data: Zhengjian Li, Desheng Chen. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Ziqiang Huo, Meng Xi. Statistical analysis: Yang Li, Jiachen Yang. Writing of the manuscript: Ziqiang Huo, Jiabao Wen. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Meng Xi, Jiachen Yang. All authors read and approved the fnal draf.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huo, Z., Wen, J., Li, Z. et al. Spatial interpolation of global DEM using federated deep learning. Sci Rep 14, 22089 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72807-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72807-z

This article is cited by

-

Harnessing Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) for Environmental Epidemiology: A Narrative Review

Current Environmental Health Reports (2025)