Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is associated with a high prevalence of unwanted loneliness. This study aimed to assess whether unwanted loneliness was associated with adverse clinical endpoints in HF patients. Additionally, we also aimed to examine the risk factors associated with unwanted loneliness in HF. We included 298 patients diagnosed with stable HF. Clinical, biochemical, echocardiographic parameters and loneliness using ESTE II scale were assessed. We analyzed the association between the exposure and adverse clinical endpoints by Cox (death or any hospitalization), and negative binomial regressions (recurrent hospitalizations or visits to the emergency room). Risk factors associated with loneliness were analyzed using logistic regression. The mean age was 75.8 ± 9.4 years, with 111 (37.2%) being women, 53 (17.8%) widowed, and 154 (51.7%) patients having preserved ejection fraction. The median (p25–p75%) ESTE II score was 9.0 (6.0–12.0), and 36.9% fulfilled the loneliness criteria (> 10). Both women (OR = 2.09; 95% CI 1.11–3.98, p = 0.023) and widowhood (OR = 3.25; 95% CI 1.51–7.01, p = 0.003) were associated with a higher risk of loneliness. During a median follow-up of follow-up of 362 days (323–384), 93 patients (31.3%) presented the combined episode of death or all-cause admissions. Loneliness was significantly related to the risk of time to the composite of death or any readmission during the composite (HR = 1.83; 95% CI 1.18–2.84, p = 0.007). Women and widowhood emerge as risk factors for unwanted loneliness in HF patients. Unwanted loneliness is associated with higher morbidity during follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome with a high and increasing prevalence1. In addition to its high morbidity and mortality, recent studies in North American and Central European populations suggest that, in chronic pathologies such as HF, unwanted loneliness is common2,3. However, the factors associated, and their clinical implications are not well defined4.

There are many types of scales to assess loneliness. Among them, the ESTE II score is widely used5. This scale considers the social dimensions components of loneliness as key points, especially in older adults. Patients experiencing unwanted loneliness face a higher risk of deteriorating mental and physical health, which can worsen chronic conditions6. Loneliness may lead to increased anxiety and stress7, unhealthy lifestyle habits8, and lack of therapeutic adherence9. All of them are factors that may contribute to the increased morbimortality burden in HF. However, the evidence assessing the role of loneliness on clinical status and disease progression in HF is limited, especially accounting for well-established surrogates of disease severity10,11,12. Biological, psychological, and social factors could underline the deleterious consequences of unwanted loneliness on health.

In this manner, we speculate that unwanted loneliness could be associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical events. In the present study, we sought to evaluate the association between unwanted loneliness and the risk of adverse clinical endpoints during follow-up in a population with chronic HF. Additionally, we aimed to assess the factors associated with the presence of unwanted loneliness in this population.

Methods

Study population and procedures

We conducted a single-center, cross-sectional, prospective study including an unselected cohort of patients meeting the HF criteria, according to the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines 202113.

The study sample consisted of 298 consecutive patients who attended the Heart Failure Unit of the Cardiology Service of the Hospital Clínico Universitario of Valencia from May 2022 to July 2022 and agreed to participate. Patients were included regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

During the baseline visit, we collected demographic data (age, sex), clinical data (weight, edema, jugular venous distention, body mass index, and medical history), vital signs (heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation), electrocardiogram, and laboratory parameters (NT-proBNP, CA125, urea, creatinine, uric acid, sodium, potassium, and hemoglobin), echocardiographic LVEF, and pharmacological treatment. We obtained demographic, clinical, and analytical parameters on the same day as the loneliness questionnaire results. Echocardiographic parameters were extracted from the patient’s medical history, using values closest to the baseline visit.

Assessment of unwanted loneliness

We evaluated unwanted loneliness using the validated ESTE II questionnaire5. This questionnaire evaluates unwanted loneliness considering three factors including the perception of social support, the use of new technologies and the subjective social participation index. The questions that underlie each of the questionnaire factors are reflected in Fig. 1. The total score ranges between 0 and 30, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. Based on the score obtained in each of the responses, we classified patients into three established levels of unwanted loneliness5: low (0–10), medium (11–20) and high (21–30).

ESTE II scale5.

Follow-up and endpoints

We recorded all-cause admissions and all-cause urgent visits during the follow-up. The primary endpoint was the composite of time to death or hospital admission for all causes. Secondary endpoints were: (a) factors associated with loneliness; (b) recurrent all-cause hospital admissions; and, (c) the composite of total all-cause admissions or visits to the emergency department during follow-up. We defined admission as any unscheduled hospital stay > 24 h and emergency visits as unplanned visits ≤ 24 h. The personnel in charge of endpoint adjudications were blinded to the grade of unwanted loneliness survey.

Statistical analysis

We expressed continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or median (25% percentile—75% percentile), as appropriate. We presented categorical variables as percentages. We evaluated differences between baseline variables and unwanted loneliness using the chi-square test for categorical variables and T-test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. We used regression to evaluate risk factors associated with loneliness (ESTE score > 10). We present results as odds ratios (OR). We used multivariate Cox regression to examine the association between loneliness and time to the first adverse event, presenting results as hazard ratios (HR). For recurrent events (all events during follow-up: all-cause hospitalizations, emergency visits, or death), we used negative binomial regression and presented risk differences as incidence rate ratios (IRR).

We selected covariates in multivariate models based on biological plausibility, regardless of p-value.

For the primary endpoint (time to death of first hospitalization) and recurrent events, the Cox regression and negative binomial regression included the following covariates: loneliness (yes/no), age (years), female (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), dyslipemia (yes/no), type 2 DM (yes/no), prior acute myocardial infarction (yes/no), valvular etiology (yes/no), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (mmHg), New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (I-II vs III-IV), LVEF (%) and NT-proBNP (pg/ml). The final multivariate models for the logistic regression included the following covariates: age (years), female (yes/no), widowed (yes/no), New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (≥ 3), LVEF (%), previous history of Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) (yes/no), type 2 DM (yes/no), previous history of stroke (yes/no), cancer (yes/no) and NT-proBNP (pg/ml).

We conducted all analyses with STATA 16.1 [Stata Statistical Software, Release 16 (2019); StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA].

Ethics statement

The Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico Universitario of Valencia approved the study in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed consent.

Results

Basal characteristics

The mean age of the sample was 75.8 ± 9.4 years, 111 (37.2%) were women, 53 (17.8%) were widows, 154 (51.7%) showed HF with preserved LVEF, and 260 (87.2%) were in stable NYHA II functional class. The median value (p25–p75%) of the ESTE II score was 9.0 (6.0–12.0) and 36.9% showed unwanted loneliness > 10. Subjects with unwanted loneliness were older [79.0 (72.0–86.0) vs. 75.0 (67.0–81.0), p < 0.001]; more frequently women [63 (54.8%) vs. 52 (45.2%), p < 0.001]; and more were in a state of widowhood [38 (33.0%) vs. 15 (8.2%), p < 0.001]. Regarding clinical variables, unwanted loneliness was more frequent in patients with NYHA III/IV functional class [15 (13.1% vs. 14 (7.7%), p = 0.032]), also showing lower weight [73 0.1 (63.4–85.3) vs. 76.8 (70.7–88.9), p = 0.011]; worse estimated glomerular filtration rate [49.6 (37.1–61.8) vs. 55.9 (38.9–75.2), p = 0.017]; and less history of AMI [10 (8.7%) vs 41 (22.4%), p = 0.002]. The baseline characteristics of the population according to the presence of unwanted loneliness are shown in Table 1.

Risk factors associated with loneliness

The independent factors associated with the presence of unwanted loneliness were female sex (OR = 2.09; 95% CI 1.11–3.98, p = 0.023) and widowhood (OR = 3.25; 95% CI %:1.51 –7.01, p = 0.003). On the contrary, a history of previous AMI showed an inverse significant association (OR = 0.39; 95% CI 0.17–0.89, p = 0.025) (Fig. 2). Variables related to the severity of HF, such as NYHA functional class (p = 0.293), comorbidities [DM (p = 0.095) and stroke (p = 0.073)], LVEF (p = 0.488), NT-proBNP (p = 0.248) and glomerular filtration rate (p = 0.398), were not associated with the risk of loneliness.

Risk factors associated with unwanted loneliness. Loneliness was significantly associated with female sex and widowhood, and inversely associated with history of previous AMI. AMI: Acute myocardial infarction. This illustration was created using BioRender, version updated as of January 2024. (URL: https://www.biorender.com/).

Unwanted loneliness and adverse clinical events

Morbimortality risk

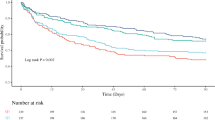

During a median (p25–p75%) follow-up of 362 days (323–384), we recorded 22 deaths (7.4%), and 84 patients were readmitted (28.3%). A total of 93 patients (31.3%) presented the combined episode of death or all-cause admissions. The risk of this combined endpoint was higher in those with self-perceived loneliness (5.1 vs. 3.3 per 10-person-year, p = 0.021), with differences that increased progressively throughout follow-up (Fig. 3). Adjusted multivariate Cox regression confirmed that unwanted loneliness increased the risk of dying or being admitted for any cause during follow-up (HR = 1.83; 95% CI 1.18–2.84, p = 0.07). The results of the adjusted Cox regression, including the covariates and risk estimates, are shown in Table 2.

Recurrent admissions and visits to the emergency room

During follow-up, we registered 102 hospitalizations in 84 patients (28.3%), and 391 all-cause hospitalizations or emergency visits in 168 patients (56.4%). HF caused a total of 34 hospitalizations in 27 patients. The risk of any-readmission was significantly higher in those with unwanted loneliness (6.7 vs. 4.4 per 10 person-years, p = 0.031). These risk differences were maintained after multivariate adjustment. Thus, unwanted loneliness doubled the risk of admission for all causes (IRR = 2.05; 95% CI 1.24–3.40, p = 0.005). When we evaluated the association between self-perceived loneliness and the risk of total any-readmission or visits to the emergency room, we also found increased rates in those with loneliness (16.3 vs. 12.9 per 10 person-year, p = 0.029). This increased risk was also maintained after multivariate analysis (IRR = 1.42; 95% CI 1.02–1.96, p = 0.037).

Discussion

In this study, we found that in patients with HF, female sex and widowhood are factors associated with unwanted loneliness, while a history of AMI is associated with lower risk. It also confirms that self-perceived loneliness is associated with a greater risk of adverse clinical events during follow-up. From Sullivan’s14 definition to the present, loneliness has gained relevance as a risk factor that contributes negatively to mental health, physical health, health behavior, and the risk of death11,15,16,17. Simultaneously, concepts related to loneliness have been narrowed down (including loneliness and social isolation), and multiple scales have been developed for research18. Although not universally adopted, the WHO defines “loneliness” as a painful subjective feeling—“social pain”—resulting from a discrepancy between desired and actual social connections, and “social isolation” as the state goal of having a small network of family and non-family relationships and, therefore, few or infrequent interactions with others11. The ESTE II Social Loneliness Scale was developed and validated at the University of Granada-Spain in 2009 and was targeted to a population older than 65 years old. This score delves into social loneliness, understood as the perception and experience of a subject, and about their membership in a social network5.

Loneliness in HF: previous evidence

The association between loneliness-social isolation and health deterioration is bidirectional19,20. Most studies linking unwanted loneliness and HF have focused on investigating the role of loneliness and/or social isolation as a risk factor for developing HF. There is a consistent association between loneliness and/or social isolation with coronary heart disease21,22,23. However, the evidence for an association between unwanted loneliness and the development of HF is limited and inconclusive, probably due to heterogeneity in the definition. A prospective study of a cohort of men between 60 and 79 years selected from General Practice Clinics in 24 British cities stated that low social contact increased the risk of HF24. In another study, Cené et al. showed that social isolation increased the risk of HF independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in a cohort of postmenopausal women without a previous diagnosis of HF from the Women’s Health Initiative10. Similarly, in a population cohort extracted from the UK Biobank database, Liang et al. concluded that loneliness and social isolation are independently associated with the development of HF regardless of genetic risk25.

The scientific literature related to unwanted loneliness and the factors associated with patients already diagnosed with HF is also scarce. In the current study, the percentage of loneliness in patients with HF was 36.9%. Previous studies show quite different figures for unwanted loneliness, ranging from 20 to 78%26,27,28. Presence of medium–high grade of loneliness was more homogeneous (20–25%) with validated scales26,27 than when loneliness was measured with non-validated scales (78%)28. In Spain, the prevalence of unwanted loneliness in people aged 65 or older is about 20%, being slightly higher in women29. The high prevalence of loneliness in this study may obey to different reasons: (a) the type of the scale used; (b) older age; (c) the chronic nature of HF; (d) sample size; and (e) the type of population here evaluated (most of them with features of advanced HF)30,31,32. The present results show that loneliness in patients with HF was associated with female sex (a result that agrees with the rest of the studies in patients with HF)26,27,28 and with widowhood. Widowhood has not usually been evaluated in this particular context. However, previous studies suggest that, in patients with HF, being married27 or living with someone26 is shown to be inversely related to the development of social isolation or loneliness. In the same sense, living alone was a risk factor for the development of loneliness in multi-pathological patients over 50 years of age in Southeastern Europe33.

What stands out in our study is the result that links a history of AMI as a factor inversely related to the presence of unwanted loneliness. Previous studies have not shown any relationship between a history of ischemic heart disease and loneliness in this patient profile26,27. As mentioned previously, loneliness is a risk factor for the development of ischemic heart disease and has been equated to other traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and smoking16. It is, therefore, striking that, in our study, a history of AMI was inversely associated with loneliness. The reasons explaining this association remain elusive. However, we speculate that the story of AMI culturally resonates as a serious situation. This is why perhaps the people closest to the patient with previous AMI increase their ties to them, thus decreasing the perception of loneliness. Furthermore, patients with ischemic heart disease appear to be the main beneficiaries of cardiac rehabilitation programs that, at least initially, increase social contact34.

Prognostic implications: the importance of measuring unwanted loneliness in HF

The increased morbimortality and use of health care resources related to loneliness has been reported in different clinical scenarios and on several occasions since the original study by Gellers et al.16,26,27,29. Regarding the increase in mortality, a recent meta-analysis35 concluded that, in the general population, loneliness and social isolation were significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause death in the whole sample and in individuals with cardiovascular disease. In this manner, the present results confirm the association between unwanted loneliness and worse clinical outcomes already observed in different other clinical contexts.

The present work confirms the high prevalence of unwanted loneliness in HF, but also adds novel and relevant information about its clinical consequences. Specifically, this is the first work to show that unwanted loneliness in Spain may be associated with a greater risk of adverse clinical events in patients with established HF.

The causes that explain the association between unwanted loneliness and poorer clinical outcomes in HF seem to be multifactorial and not fully understood. We speculate, the following, may play a role: (a) loneliness will lead to greater anxiety and stress due to symptoms/signs of the disease7, (b) unhealthy lifestyle habits8, (c) lack of therapeutic adherence9, and (d) biological factors36.

Given the high prevalence and deleterious repercussions, it seems reasonable to suggest that the evaluation of unwanted loneliness should be done more routinely in the HF care setting. In this way, identifying the most vulnerable patients could be followed by a closer clinical approach with implementation of dedicated social/psychological intervention strategies aiming to reduce the feeling of loneliness. How these strategies can contribute to better care and clinical results deserves to be the subject of prospective studies dedicated to this.

Limitations

Several limitations in this study must be acknowledged. Firstly, this is an observational study in which numerous confounding factors may be operating. Second, this study was carried out in a single center, and there may be a selection bias that makes it difficult to extrapolate results to other settings. Third, this study is not designed to understand the social/cultural/psychological/biological mechanisms behind the present findings. Fourth, the power of the present study does not allow us to evaluate clinical adverse events such as mortality in isolation and specific readmissions due to HF.

Conclusions

In this contemporary cohort of outpatients with HF, we found a high prevalence of unwanted loneliness, which was more common in women and widows. Its presence was associated with worse clinical outcomes during follow-up.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CA125:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 125

- DM:

-

Mellitus diabetes

- DL:

-

Dyslipidemia

- ESC:

-

European society of cardiology

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- IRR:

-

Internal rate of return

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- NYHA:

-

New York association class

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

References

Groenewegen, A., Rutten, F. H., Mosterd, A. & Hoes, A. W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail.22, 1342–1356 (2020).

Goodlin, S. J. & Gottlieb, S. H. Social isolation and loneliness in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail.11, 345–346 (2023).

Olano-Lizarraga, M., Wallström, S., Martín-Martín, J. & Wolf, A. Causes, experiences and consequences of the impact of chronic heart failure on the person´s social dimension: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community.30, e842–e858 (2022).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System (National Academies Press, Washington, 2020). https://doi.org/10.17226/25663.

Marín, M. A. et al. Contraste de un modelo de envejecimiento exitoso derivado del modelo de Roy. Cienc.-Sum.24, 126–136 (2017).

Holwerda, T. J. et al. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the amsterdam study of the elderly (AMSTEL). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry.85, 135–142 (2014).

Trtica, L. M. et al. Psycho-social and health predictors of loneliness in older primary care patients and mediating mechanisms linking comorbidities and loneliness. BMC Geriatr.23, 801 (2023).

Zheng, D. et al. Impact of an intergenerational program to improve loneliness and social isolation in older adults initiated at the time of emergency department discharge: Study protocol for a three-arm randomized clinical trial. Trials.25, 425 (2024).

Fan, Y., Shen, B.-J. & Ho, M.-H.R. Loneliness, perceived social support, and their changes predict medical adherence over 12 months among patients with coronary heart disease. Br. J. Health Psychol.https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12732 (2024).

Cené, C. W. et al. Effects of objective and perceived social isolation on cardiovascular and brain health: A scientific statement from the american heart association. J. Am. Heart Assoc.11, e026493 (2022).

WHO. in Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Older People: Advocacy Brief. (World Health Organization, 2021). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030749.

Núñez, J. et al. Congestion in heart failure: A circulating biomarker-based perspective. A review from the biomarkers working group of the heart failure association, European society of cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail.24, 1751–1766 (2022).

McDonagh, T. A. et al. Guía ESC 2021 sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la insuficiencia cardiaca aguda y crónica. Rev. Esp. Cardiol.75(523), e1–523.e114 (2022).

Cortina, M. Harry stack sullivan and interpersonal theory: A flawed genius. Psychiatry.83, 103–109 (2020).

Umberson, D. & Montez, J. K. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J. Health Soc. Behav.51, S54–S66 (2010).

Freedman, A. & Nicolle, J. Social isolation and loneliness: The new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can.66, 176–182 (2020).

Barjaková, M., Garnero, A. & d’Hombres, B. Risk factors for loneliness: A literature review. Soc. Sci. Med.334, 116163 (2023).

Veazie, S., Gilbert, J., Winchell, K., Paynter, R. & Guise, J.-M. Addressing Social Isolation To Improve the Health of Older Adults: A Rapid Review (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2019).

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med.1982(74), 907–914 (2012).

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Shmotkin, D. & Goldberg, S. Loneliness in old age: Longitudinal changes and their determinants in an Israeli sample. Int. Psychogeriatr.21, 1160–1170 (2009).

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S. & Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart Br. Card. Soc.102, 1009–1016 (2016).

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S. & Hanratty, B. Loneliness, social isolation and risk of cardiovascular disease in the english longitudinal study of ageing. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol.25, 1387–1396 (2018).

Naito, R. et al. Impact of social isolation on mortality and morbidity in 20 high-income, middle-income and low-income countries in five continents. BMJ Glob. Health.6, e004124 (2021).

Coyte, A. et al. Social relationships and the risk of incident heart failure: Results from a prospective population-based study of older men. Eur. Heart J. Open.2, oeab045 (2022).

Liang, Y. Y. et al. Association of social isolation and loneliness with incident heart failure in a population-based cohort study. JACC Heart Fail.11, 334–344 (2023).

Löfvenmark, C., Mattiasson, A.-C., Billing, E. & Edner, M. Perceived loneliness and social support in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs.8, 251–258 (2009).

Manemann, S. M. et al. Perceived social isolation and outcomes in patients with heart failure. J. Am. Heart ASSOC.7, e008069 (2018).

Polikandrioti, M. Perceived social isolation in heart failure. J. Innov. Card. Rhythm Manag.13, 5041–5047 (2022).

Martín Roncero, U. & González-Rábago, Y. Soledad no deseada, salud y desigualdades sociales a lo largo del ciclo vital. Gac. Sanit.35, 432–437 (2021).

Ong, A. D., Uchino, B. N. & Wethington, E. Loneliness and health in older adults: A mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology.62, 443–449 (2016).

Yanguas, J., Pinazo-Henandis, S. & Tarazona-Santabalbina, F. J. The complexity of loneliness. Acta Bio-Med. Atenei Parm.89, 302–314 (2018).

Petitte, T. et al. A systematic review of loneliness and common chronic physical conditions in adults. Open Psychol. J.8, 113–132 (2015).

Cantarero-Prieto, D., Pascual-Sáez, M. & Blázquez-Fernández, C. Social isolation and multiple chronic diseases after age 50: A European macro-regional analysis. PLoS One.13, e0205062 (2018).

Levinger, P. et al. Exercise interveNtion outdoor proJect in the cOmmunitY for older people—Results from the ENJOY seniors exercise park project translation research in the community. BMC Geriatr.20, 446 (2020).

Yang, M. et al. Relationship between physical symptoms and loneliness in patients with heart failure: The serial mediating roles of activities of daily living and social isolation. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.24, 688–693 (2023).

Henriksen, R. E., Nilsen, R. M. & Strandberg, R. B. Loneliness as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome: Results from the HUNT study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health.1979–73, 941–946 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from CIBER CV (Madrid, Spain) [grant number 16/11/00420]; FEDER (Madrid, Spain), Instituto Carlos III (Madrid, Spain). The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose regarding this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally: T.B, G.Z. C.J and J.N conceived the study and designed the experiments. C.J, C.M, E.B, F.C, J.C contribute to data collection. A.P,C.J and J.N design the database and statistical analysis. T.B and G.Z contribute equally to the redaction of the manuscript supervised by J.N, A.M and M.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benito, T., Zaharia, G., Pérez, A. et al. Risk factors and prognostic impact of unwanted loneliness in heart failure. Sci Rep 14, 22229 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72847-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72847-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Social isolation, loneliness and the relationship with serum biomarkers, functional parameters and mortality in older adults

Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2025)