Abstract

Music is a promising (adjunctive) treatment for both acute and chronic pain, reducing the need for pharmacological analgesics and their side effects. Yet, little is known about the effect of different types of music. Hence, we investigated the efficacy of five music genres (Urban, Electronic, Classical, Rock and Pop) on pain tolerance. In this parallel randomized experimental study, we conducted a cold pressor test in healthy volunteers (n = 548). The primary outcome was pain tolerance, measured in seconds. No objective (tolerance time) or subjective (pain intensity and unpleasantness) differences were found among the five genres. Multinomial logistic regression showed that overall genre preference positively influenced pain tolerance. In contrast, the music genres that participants thought would help for pain relief did not. Our study was the first to investigate pain tolerance at genre level and in the context of genre preference without self-selecting music. In conclusion, this study provides evidence that listening to a favored music genre has a significant positive influence on pain tolerance, irrespective of the kind of genre. Our results emphasize the importance of individual music (genre) preference when looking at the analgesic benefits of music. This should be considered when implementing music in the clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is a worldwide problem with a high prevalence in the hospital and ambulatory setting1,2. Pain management, which includes the use of analgesics such as opioids and NSAIDs, is an essential component of perioperative care3. Adequate pain management is crucial for healthcare-related outcomes4. However, pharmacological pain management can lead to various side effects, some of which could be mitigated by the use of music as an adjunctive pain treatment5,6. The implementation of recorded music for hospitalized patients has demonstrated benefits in addressing issues such as pain, anxiety, and stress7,8,9. Moreover, music shows benefits in chronic pain conditions, and evidence indicates that listening to music lowers the requirement of analgesics in patients undergoing surgery10,11.

Several theories explain how music influences the human body and reduces pain12,13. These theories include distraction, hormone release and emotion regulation, which involve changes in physiological arousal. Additionally, context factors such as individual pain beliefs, music familiarity, cultural and social functions, and music preference can significantly impact these mechanisms14,15. Although the precise mechanisms underlying pain reducing effect of music, also described as music-induced analgesia (MIA), are not yet completely understood, there is substantial evidence that the use of music can be valuable in healthcare.

Importantly, music should not be seen as a generalized and homogenous intervention. As music has diverse characteristics and dimensions - such as rhythm, melody, and cultural connotations - these dimensions could hypothetically have varying effects on MIA16. Previous studies have provided insight into the importance of music genre and its characteristics, including for example, the suggestion that classical music might be more effective than heavy metal music17,18,19,20. The notion that calm and/or classical music is more effective may be shaped by unsubstantiated stereotypes, potentially linked to the high prevalence of (preferences for) such music in clinical studies21. Furthermore, recent research suggests that self-selected and preferred music is more effective for pain relief22,23,24. However, the description of music used in clinical trials often lacks preciseness and transparency18. Direct comparisons of different music genres and the influence of these genres on pain tolerance are limited.

Genre is a conceptual tool that is used to categorize a variety of cultural products, including art, literature, film and music25,26. Sociological research in particular has investigated contextual differences in music genre reception and audience segmentation. This research has demonstrated that genre preferences tend to be related to social background characteristics such as class, status, ethnicity and gender26,27,28. Importantly, the structure underlying such music genre preferences is affected by both the sonic characteristics of the music itself and the genre’s social associations16,27,28. Genres are conventional categorizations and they are, therefore, to some extent open to subjective interpretation. However, genres have an important role in how people understand and talk about music, and thus in how people define and identify their music preferences. Therefore, to implement MIA targeted to individual patients, it is crucial to study music genres in the context of music preference and pain tolerance.

Currently, it is unknown whether certain genres are more effective for (acute) pain than others, irrespective of patients’ genre preferences. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate how different music genres affect the pain tolerance of healthy volunteers and how this relates to personal music genre preferences.

Methods

Participants

Healthy volunteers aged ≥ 18 years were included. We carefully selected exclusion criteria to ensure valid results and participant safety, based on previous research22,29,30. Specifically, we aimed to exclude potential factors that could influence pain tolerance or impact the experience of listening to recorded music. A blood alcohol percentage above 0.5‰ was handled as an exclusion criterion (based on the analgesic potential of alcohol31), and was objectified using an ACE Breathanalyser AF-33 before inclusion. Other exclusion criteria were based on self-reported information by the participant: usage of recreational drugs within the last 24 h, usage of analgesic drugs within the last 12 h, usage of psychiatric medication, chronic or acute pain conditions, a medical history of cardiovascular diseases, pregnancy and/or any kind of hearing problems. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki32. The protocol (ETH2223-0710) was approved by the ESHCC Research Ethics Review Committee of Erasmus University Rotterdam (Rotterdam, The Netherlands). Volunteers received no (financial) compensation for their participation.

Setting and study design

This experimental field study was conducted from August 18th to 20th 2023 at ‘Lowlands Science’, a dedicated science area at the three-day Lowlands Music Festival (Biddinghuizen, the Netherlands, ~ 65 000 visitors)33. Lowlands Science is located in a separate area at the festival, offering all infrastructure needed for scientific research (see Suppl. Figure 1)34,35. Participants were recruited exclusively within this designated research area. Posters with information and inclusion/exclusion criteria were prominently displayed, and a researcher stationed outside the research room provided additional information about the experiment (Suppl. Figure 1).

This randomized experimental trial had a five-armed parallel design. First, participants were recruited, screened and requested to provide written informed consent. Next, exclusion criteria were checked again and participants were randomized into one of the five music genres. Participants were not given any control over, or prior knowledge of, the music genre they were going to listen to. The music genre that participants listened to remained undisclosed while completing the ‘baseline questionnaire’ about music preferences and personal background. Subsequently, the music listening task and cold pressor test (CPT), while still listening to music, were conducted. Finally, participants completed a ‘debriefing questionnaire’, after which the study was completed.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization was performed using a 10-sided dice, following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions36. Every two numbers were assigned to one of the five selected music genres: 1 and 2 corresponded to Urban; 3 and 4 to Electronic; 5 and 6 to Classical; 7 and 8 to Rock; and 9 and 10 to Pop. The allocation sequence was concealed from the participants by not telling which numbers corresponded to which genres and by not actively revealing the music genre participants were going to listen to until after the experiment. Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and researchers were not completely blinded to the intervention.

Music genres and music selection

The selection of the five music genres for our study was two-fold. First, we used prior quantitative research that identified overarching clusters within music preferences16,37. Each of the chosen genres corresponded to a five-factor structure underlying music preferences, which aligns with broader genre categories37. Moreover, this categorization was also in line with the components of a validated five-factor model that captures music preferences beyond genre labels, focusing instead on the emotional and affective responses elicited by music16. Second, seeing that predetermined genre categories are best suitable within the cultural context of participants38, genre categories were also checked against the way they were categorized by the Lowlands festival, which should bear strong familiarity with visitors. In the festival’s genre classification of performing artists, two categories were comparable to, but had slightly different wordings than the study of Franken et al.; ‘Classical’ and ‘Electronic’, which we in turn incorporated into our genre definitions to make them clearer to participants37. Therefore, the five genres were as follows: Urban, Rock, Classical, Electronic and Pop. Genres are by definition conventional categories, which are open to subjective interpretation. Therefore, we also included a factor analysis to substantiate our genre classification based on more specific subgenre categories to address the potential variability in genre perception among participants. These subgenre categories consisted of 15 options that were again based on the two aforementioned studies (alternative rock/indie; folk; gothic; hardhouse/hardstyle; heavy metal/metal; house/dance/trance/EDM; jazz; classical music; Dutch popular music; pop (international); rap/hip hop; reggae/dub; rock/punk; RnB/soul; techno/dubstep/drum ‘n bass)16,37. This operationalization was substantiated by the factor analysis, confirming the five genre clusters (“section Music preference ratings”).

Only tracks from artists scheduled to perform at the Lowlands festival in 2023 were chosen (Suppl. Table 1). This approach increased the likelihood that the selected artists were familiar to participants, enabling them to rank their music preferences with respect to these artists. Music tracks were shortened to fragments with a length of 45 s, compiled in a compilation of 7 min of uninterrupted music with brief fade-ins/outs. Although using complete songs rather than music fragments arguably corresponds more to the ordinary engagement of people with music, this approach ensures comparability between conditions and serves variety. By using those compilations, we aimed to rule out the possibility that individual songs affect reactions disproportionately. The track sequence in a genre condition remained identical and each fragment contained key segments of the song (e.g. verse and chorus, beat drops, crescendos).

Measurements

Baseline questionnaire

Baseline characteristics (gender, age, nationality, level of education, parents’ level of education, smoking) and music preferences were assessed at the beginning of the experiment39. Participants were asked to rate their Overall Genre Preferences (OGP) for the five genres provided and subjectively estimate their effectiveness against pain (Genre Against Pain (GAP)) on a 7-point Likert scale (from very bad to very good). Additionally, from the 15 subgenre categories, participants were asked to choose their (least) favored subgenre(s) and subgenre(s) expected to help against pain. This involved multiple choice options (at least one, no maximum).

Music listening task and CPT

After the baseline questionnaire, the music listening task and CPT were performed in one of six identically designated cubicles. Each participant listened to one of the five music genres in which they were randomized. Right before, standardized instructions for the music listening task and CPT were given by the researcher, including instructions to endure the test for as long as possible. Next, the participant listened to the music for 4 min, without doing anything else (focusing on the music) through noise-canceling headphones (JBL Tune 770 NC). Participants could self-adjust the volume to a comfortable level. Next, the CPT started with a visual signal from the researcher, while the participant continued to listen to the music. The CPT was conducted using polystyrene buckets filled with ice water at a temperature of ~ 2 °C (range 0–4 °C). Before each measurement, the water temperature was monitored and adjusted if necessary. The researcher then measured the pain tolerance in seconds, and monitored the proper execution of this test, which included maintaining water 3 cm above wrist level, with the hand palm facing downwards, fingers slightly spread apart, and regular hand movements to prevent the water from warming around the hand. The researcher measured the time when the participant discontinued the task. Unbeknownst to the participant, the task was automatically stopped after 3 min, a cut-off value that was based on previous research to ensure both valid data acquisition and participant safety30,40. Directly after the CPT, participants rated the subjective intensity and unpleasantness of the pain on a numeric rating scale (NRS).

Debriefing questionnaire

In the debriefing questionnaire, participants were asked to assess their experience during the listening task, including how much they liked the music, whether they felt it helped alleviate their pain, and how familiar the music was to them. Responses to these questions were recorded on a 7-point Likert scale. A qualitative open question regarding the participants’ experiences during the experiment was included in the debriefing questionnaire. An overview of the debriefing questionnaire results can be found in Suppl. Tables 2 and 3.

Statistical analysis

All data were initially collected on paper. Following the completion of the experiment, data entry, data validation, and statistical analysis were conducted using SPSS (IBM Corp., Chicago, USA) version 28.0. Data visualization was performed using R (version 4.3.2) and R-Studio (version 2022.07.2) with the following packages: dplyr, ggplot2, ggridges, and ggdist. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation were utilized. Ordinal variables were characterized using medians and percentiles, while nominal variables were summarized using percentages. Considering the non-normal distribution of the data, the Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized to compare the baseline characteristics, the pain tolerance (seconds) and subjective pain scores between the five music genre conditions. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the multiple-choice music genre preference question using principal component analysis. An eigenvalue greater than 1 was used as the criterion for determining the number of factors. To explore the relationships among various factors, Spearman’s ρ correlation coefficients were calculated. The interpretation was as follows: ρ < 0.2 (very weak), 0.2 ≤ ρ < 0.4 (weak), 0.4 ≤ ρ < 0.6 (moderate), 0.6 ≤ ρ < 0.8 (strong), and ρ ≥ 0.8 (very strong).

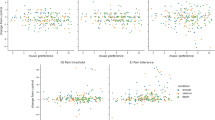

Because the primary outcome showed a pronounced non-normal distribution (pain tolerance, Fig. 2), we also utilized median and interquartile range (IQR) to describe the data. In order to create groups of sufficient sample size and minimize the loss of information, pain tolerance was subsequently categorized into three groups (I < 46.99s (n = 137), II 46.99–180 s (n = 152), III = 180 (n = 259)). The cutoff value for the first interval (I) was based on the 25th percentile. Values between this percentile and 180 s (75th percentile) were grouped into the second interval to ensure sufficient group size. Another categorization based on 60-second intervals, yielded similar results (see Suppl. Table 4). Subsequently, a multinomial logistic regression model was conducted to investigate the potential influence of music preference and other variables on pain tolerance. Three models were conducted to illustrate the impact of OGP (Model 1) and GAP (Model 2) separately, and both added simultaneously (Model 3). All other independent variables remained constant across these models. Additionally, linear multivariable regression analyses were conducted using subjective pain scores (both pain intensity and pain unpleasantness) as dependent variables.

Results

Study population characteristics

In total, 626 participants provided informed consent (Fig. 1). Among these, 548 participants were included in the study. Most of the exclusions before randomization (n = 74) were due to blood alcohol concentrations > 0.5‰ (n = 73). The five randomized genre groups were comparable in size with an average of 110 participants per group.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Participants were predominantly female (57.5%) and higher educated (91.2%). The parents’ highest level of education showed a tendency towards lower and medium levels of education. The mean age was 30.6 ± 9.1 years and most of the participants were non-smokers (61.1%), excluding former smokers. None of the baseline characteristics differed among the five genre groups (p > 0.05).

Comparison of music genres

An overview of the results of the CPT can be found in Table 2. The average pain tolerance was 115.5 ± 66.8 s (median 145,6 (IQR 47.0-180.0)), with no significant difference between the five music genres (p = 0.67). A visualization of the frequency of the pain tolerance per genre to which participants listened can be found in Fig. 2. Almost half of the participants endured the maximum of 180 s (47.3%). An additional peak emerged at approximately 50 s tolerance time. The pain intensity and pain unpleasantness (NRS) were 6.2 ± 1.7 and 6.4 ± 2.0, respectively. Among the five genre groups, there was no significant difference in terms of pain tolerance (p = 0.67), pain intensity (p = 0.90) or pain unpleasantness (p = 0.99).

Histograms of pain tolerance (seconds) per music genre. The five histograms visualize the frequency of the pain tolerance in seconds (cold pressor test) per music genre to which participants listened. The distribution was not significantly different between the five genres (p = 0.669). Almost half of the participants endured the maximum of 180 s.

Music preference ratings

A factor analysis of the 15 subgenres categories revealed the five genre clusters, in line with previous literature (Suppl. Table 5)16,37. Moreover, those five genres showed a moderate positive correlation with the OGP obtained with the Likert scale (urban: ρ = 0.43; electronic: ρ = 0.53; classical: ρ = 0.45, rock: ρ = 0.58, pop: ρ = 0.47; p < 0.001) for each genre. This indicates that categorizing the more detailed subgenre ratings into our five main genres was an adequate method for quantifying musical preference.

Analysis at subgenre category level revealed that classical music, jazz and rhythm and blues (R&B)/soul were more frequently chosen against pain, whereas pop and alternative rock/indie emerged as the most popular subgenre categories, both as favorite music and for pain relief (Suppl. Table 6). Comparing the GAP with the OGP rating (both on a 7-point Likert scale), the genres urban, electronic and rock received lower ratings, while classical and pop music received higher ratings (Table 3). Nevertheless, both ratings showed a moderate to strong positive correlation (ρ (rho) 0.62, p < 0.001 for the genre to which participants listened). When looking at identical GAP and OGP ratings (within a range of ± 1 point on the 7-point Likert scale), this was observed in 64.3% (rock) to 73.5% (urban) of the participants. This suggests that the effectiveness rating of the GAP considerably stands in line with one’s individual OGP.

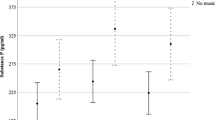

The influence of music preference and other variables

Table 4 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis, showing the influence of baseline characteristics and genre preferences in relation to pain tolerance. The OGP of the genre to which participants listened significantly influenced pain tolerance (Model 1: II, OR = 1.21, 95% CI [1.03, 1.41]; III, OR = 1.18, 95% CI [1.03, 1.36]). In contrast, the GAP rating had no effect (Model 2: II, OR = 1.14, 95% CI [1.00, 1.30]; III, OR = 1.08, 95% CI [0.96, 1.22]). Results were mostly similar when both OGP and GAP were included in the same model (Model 3). Figure 3 visualizes these results: a stronger preference for the particular genre (as indicated before the test) that participants listened to during the test was associated with a prolonged pain tolerance. Contrarily, a higher score for the perceived effectiveness against pain of that particular genre (as indicated by the participants before the test) was not associated with pain tolerance. Looking at other independent variables, both male and younger participants had a higher pain tolerance.

Mean of pain tolerance (seconds) per rating of the music genre to which participants listened. The two lines show the mean pain tolerance in seconds per point of the GAP and OGP rating (7-Point Likert scale). The figure illustrates that the OGP rating had a significant positive impact on pain tolerance, while the GAP did not. GAP: genre against pain, OGP: overall genre preference.

Subjective pain measurements

Higher pain tolerance significantly correlated with lower reported pain intensity (ρ=‒0.36, p < 0.001) and pain unpleasantness (ρ=‒0.43, p < 0.001) ratings. Among potential influencing factors (Table 5), smoking was found to have a significant impact on pain intensity with non-smokers reporting higher scores (B=‒0.30, p = 0.031). Furthermore, participants’ age and researchers’ gender were identified as factors influencing the reported pain unpleasantness. The OGP rating did not exert any distinguishable influence on either pain intensity or unpleasantness. Exploratory post-hoc analysis that took a closer look at the role of the participants’ and researchers’ gender showed that self-reported ratings of pain unpleasantness and intensity were significantly influenced by gender differences between researcher and participant (Suppl. Figures 2 and 3). Particularly, female participants reported higher pain scores to female researchers compared to male researchers.

Discussion

This randomized experimental study investigated the effect of five music genres (Urban, Electronic, Classical, Rock and Pop) on pain tolerance in 548 healthy volunteers. No difference in pain tolerance was found between the genres. However, when participants listened to a genre that matched their pre-reported genre preferences, their pain tolerance was higher. Interestingly, this effect was not observed when participants listened to genres they thought would most help them for pain relief. In conclusion, listening to non-self-chosen music genres in line with pre-reported preferences had a significant positive influence on pain tolerance.

This was the first study comparing the effect of music genres on pain tolerance. Comparing the genre against pain (GAP) with the overall genre preference (OGP) rating, classical music received higher ratings and was additionally more frequently chosen for pain relief on subgenre category level. Although it did not outperform other genres, the tendency to select classical music for pain relief might be shaped by a cultural belief that regards classical music as more ‘sophisticated’16. This potential bias is supported by the widespread claim that classical music, suggested by the so-called “Mozart Effect,” is naturally beneficial in therapeutic contexts, particularly in pain management41. The term “Mozart Effect” refers to the supposed benefits of listening to classical music from Mozart, especially KV 448, which has been associated with positive health outcomes in medical literature since 199342,43. This bias may have been originated and further reinforced by numerous studies that have exclusively employed classical music and reported its effectiveness in alleviating pain, without controlling for other genres or patient music preferences16,44,45,46. This perception could lead to a confirmation bias, where individuals are more likely to report positive outcomes when using music they believe to be more effective due to its perception of being sophisticated and inherently beneficial. It is worth noting that the participants of our study, who were visiting a festival for popular music, were also more likely to identify classical music as an effective genre against pain than to identify it as a preferred genre.

Interestingly, although the OGP and GAP ratings showed a strong correlation, only the OGP rating positively influenced the pain tolerance. In line with our results, Hauck et al. demonstrated a higher effectiveness of self-chosen preferred music in comparison to self-chosen ‘pain music’ in the context of music therapy47. Additionally, other studies have highlighted the advantages of preferred music24,48,49. Overall, the general music (genre) preference emerged as an essential factor for pain tolerance, whereas the rating of whether individuals think that a genre works against pain did not. When looking at potential working mechanisms of music such as the placebo effect12, it could be hypothesized that the music that participants think will work best, is also superior for pain relief. However, the fact that only the overall preferred music showed a positive effect on pain tolerance cautiously suggests that other working mechanisms, such as emotion regulation and distraction, might be more pivotal for the mechanism of music for pain relief13.

Although someone’s music preference (OGP) influenced pain tolerance in this study, it had no effect on the subjective pain scores (pain intensity and unpleasantness). This may potentially be evoked by the nature of the CPT itself, including the dynamic of how long the stimulus is tolerated23,29,50. In comparison, other studies that utilized pain models with a non-dynamic stimulus, demonstrated lower subjective pain scores when participants were listening to music, as compared to the control group48,51. In line with several studies, the participants’ and researchers’ gender stands out as a contributing factor when assessing subjective pain scores30,52,53.

Prior research suggests that preferred music has a stronger analgesic effect than non-preferred music22,24,48,49. The focus of our study was to investigate the impact of individual music preferences at genre level. This approach involved a more conventional categorization for the participant, rather than focusing on specific music attributes such as valence, arousal, and depth, as in the study of Basiński et al.24. By using music genres, with which participants were generally accustomed, music preferences could be assessed before, and independently from, the listened music (genre).

Other experimental studies on preferred music and MIA have used both favorite music and freedom of choice22,48. The study by Howlin et al. found that perceived control over music is associated with analgesic benefits54. Strictly speaking, the use of favorite music chosen by the subject itself constitutes a mixed intervention, raising questions about whether the positive effect of music on pain tolerance is caused by music preference, perceived control or both. In our study, participants did not have control over music selection, as participants were randomized in a genre, and did not select the songs themselves. Still, the positive effect of music preference was found. Therefore, our results indicate that music (genre) preference predicts an increased pain tolerance, independent of control over music selection.

There are several strengths and limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study. Strengths included the large sample with diverse music preferences, and the interdisciplinary team with both medical and sociological researchers who were involved in the study design and execution. The selection of the five music genre conditions and questionnaires about music genre preference were comprehensively based on previous literature, and were validated again in this study16,37. The genre in which participants were randomized was not known when the genre preference assessment was conducted. This ensured that participants were not predisposed by the music selection or experiment itself.

The largest limitations of this study were related to the festival setting, in which convenience sampling strategies were used, as participants were selected based on their availability and proximity to the research site. While this approach was most practical in the festival environment, it may not have provided a sample that accurately reflects the broader population. For example, the sample may have been biased towards participants at the festival who were typically more engaged with music and/or science, and with specific music preferences. Moreover, when interpreting our results, it is important to consider that the Lowlands festival predominantly features popular music genres. Despite the inclusion of classical music in the lineup, this setting may have introduced a selection bias towards attendees engaged in popular music, potentially influencing the genres chosen for pain relief. Conducting this study at a venue dedicated to classical music might have yielded different results and is therefore something which should be investigated in future research. Furthermore, the study setting resulted in a young, highly educated group of participants. These factors could have influenced the study’s outcomes and may limit the generalizability of our findings to the clinical setting. Next, the pain stimulus used in this study was short-term somatic pain, and it is not clear which type of pain participants had in mind when thinking about which “music [helps] against pain”. Another limitation lies in the representativeness of track selection for the five music genres. Genres are conventional categorizations of music, which means that they evolve and their meaning might differ in various times and places. That is why music genres will only be likely to be useful if they are relevant and meaningful to people. Although the genres in our study were selected from validated overarching genre clusters based on previous literature, it remains challenging to encompass the entire spectrum of a genre, especially when considering broader genre definitions such as rock and pop instead of subgenres. This might also imply that the effects demonstrated in this study might be underestimated. Exploring a similar study at subgenre level would allow a more precise definition of participants’ music tastes.

There are several possible implications of this study for clinical practice and further research. First, given that this study utilized a CPT as a nociceptive stimulus, our findings may be more transferable to the clinical setting where acute pain or ‘endurance pain’ is found (for example at the dentist or during shorter procedures such as biopsies) - and less transferable to other types of pain such as longer, neuropathic and/or chronic pain55. However, this should be investigated in future clinical studies. Furthermore, the influence of music genres should be investigated in relation to other symptoms such as anxiety and stress56,57. Second, as this study was in an experimental setting, a suggestion for future research is to investigate the effect of different music genres in clinical patients experiencing pain. Level of education is a known explanatory variable for music taste variation and our sample was skewed toward higher educated participants27. A future study could incorporate a more representative sample to investigate potential interactions between preferred genre, socio-cultural background and music’s effect on pain58. Moreover, future research could explore the impact of music choice on pain relief in more diverse populations and under consideration of biological, sociological and psychological factors. Third, our findings indicate that music that corresponds with a person’s preferred music genres predicts a greater pain tolerance compared to less preferred music genres, and could potentially enhance the efficacy of MIA. In certain clinical settings, selecting a music (sub)genre instead of creating a playlist can be more manageable for patients. Our study indicates that the OGP is more crucial than the GAP rating in the context of pain tolerance. Translating the results to the clinical setting, it seems advisable to encourage patients to select their favorite music genres – and not the music genres they think will help them against pain.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data show that listening to a favored music genre has a significant positive influence on pain tolerance, irrespective of the kind of genre. Interestingly, this effect was not observed when participants listened to genres that they had rated higher on whether they thought it would help them for pain relief. We did not find differences in pain tolerance among the five genres (Urban, Rock, Classical, Electronic, Pop). In clinical practice, practitioners should advise and support patients to listen to their favorite music genres when they are experiencing (acute nociceptive) pain.

Data availability

The data of the article are not publicly available. Data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Change history

01 October 2024

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained a previous version of the Supplementary Information file. The correct version was included with the initial submission.

References

Zimmer, Z., Fraser, K., Grol-Prokopczyk, H. & Zajacova, A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. Pain163, 1740–1750 (2022).

Goldberg, D. S. & McGee, S. J. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health11, 770. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-770 (2011).

Chou, R. et al. Management of Postoperative Pain: a clinical practice Guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J. Pain17, 131–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008 (2016).

Small, C. & Laycock, H. Acute postoperative pain management. Br. J. Surg.107, e70–e80. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11477 (2020).

Blix, H. S. et al. The majority of hospitalised patients have drug-related problems: results from a prospective study in general hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.60, 651–658 (2004).

Carter, G. T. et al. Side effects of commonly prescribed analgesic medications. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. North Am.25, 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2014.01.007 (2014).

Kühlmann, A. Y. R. et al. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br. J. Surg.105, 773–783 (2018).

Song, Y., Ali, N. & Nater, U. M. The effect of music on stress recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology168, 107137 (2024).

Maidhof, R. M. et al. Effects of participant-selected versus researcher-selected music on stress and mood – the role of gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology158, 106381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2023.106381 (2023).

Fu, V. X., Oomens, P., Klimek, M., Verhofstad, M. H. J. & Jeekel, J. The Effect of Perioperative Music on Medication requirement and hospital length of Stay: a Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg.272, 961–972 (2020).

Garza-Villarreal, E. A., Pando, V., Vuust, P. & Parsons, C. Music-Induced Analgesia in Chronic Pain conditions: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Pain Physician20, 597–610 (2017).

Lunde, S. J., Vuust, P., Garza-Villarreal, E. A. & Vase, L. Music-induced analgesia: how does music relieve pain? Pain 160 (2019).

Dingle, G. A. et al. How do music activities affect Health and Well-Being? A scoping review of studies examining psychosocial mechanisms. Front. Psychol.12https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713818 (2021).

Schäfer, T. & Sedlmeier, P. What makes us like music? Determinants of music preference. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativity Arts. 4, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018374 (2010).

Howlin, C. & Rooney, B. The cognitive mechanisms in music listening interventions for Pain: a scoping review. J. Music Ther.57, 127–167 (2020).

Rentfrow, P. J., Goldberg, L. R. & Levitin, D. J. The structure of musical preferences: a five-factor model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.100, 1139–1157 (2011).

Pastor, J., Vega-Zelaya, L. & Canabal, A. Pilot study: the Differential response to classical and Heavy Metal Music in Intensive Care Unit patients under Sedo-Analgesia. J. Integr. Neurosci.22, 30. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2202030 (2023).

Martin-Saavedra, J. S., Vergara-Mendez, L. D., Pradilla, I. & Vélez-van-Meerbeke, A. Talero-Gutiérrez, C. standardizing music characteristics for the management of pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med.41, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.07.008 (2018).

Kenntner-Mabiala, R., Gorges, S., Alpers, G. W., Lehmann, A. C. & Pauli, P. Musically induced arousal affects pain perception in females but not in males: a psychophysiological examination. Biol. Psychol.75, 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.10.005 (2007).

Labbé, E., Schmidt, N., Babin, J. & Pharr, M. Coping with stress: the effectiveness of different types of music. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback32, 163–168 (2007).

Hole, J., Hirsch, M., Ball, E. & Meads, C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet386, 1659–1671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60169-6 (2015).

Timmerman, H. et al. The effect of preferred music versus disliked music on pain thresholds in healthy volunteers. An observational study. PLoS One18, e0280036 (2023).

Howlin, C. & Rooney, B. Cognitive agency in music interventions: increased perceived control of music predicts increased pain tolerance. Eur. J. Pain25, 1712–1722. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1780 (2021).

Basiński, K., Zdun-Ryżewska, A., Greenberg, D. M. & Majkowicz, M. Preferred musical attribute dimensions underlie individual differences in music-induced analgesia. Sci. Rep.11, 8622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87943-z (2021).

Frith, S. Performing Rites: on the Value of Popular Music (Harvard University Press, 1996).

Lena, J. C. & Peterson, R. A. Classification as culture: types and trajectories of music genres. Am. Sociol. Rev.73, 697–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300501 (2008).

Lizardo, O. & Skiles, S. Cultural objects as prisms: Perceived Audience Composition of Musical genres as a resource for Symbolic Exclusion. Socius2, 2378023116641695. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023116641695 (2016).

Eijck, K. v. Social differentiation in musical taste patterns. PediatriaSocial Forces79, 1163–1185 (2001).

Choi, S., Park, S. G. & Lee, H. H. The analgesic effect of music on cold pressor pain responses: the influence of anxiety and attitude toward pain. PLoS One13, e0201897 (2018).

Schistad, E. I., Stubhaug, A., Furberg, A. S., Engdahl, B. L. & Nielsen, C. S. C-reactive protein and cold-pressor tolerance in the general population: the Tromsø Study. Pain158, 1280–1288 (2017).

Thompson, T., Oram, C., Correll, C. U., Tsermentseli, S. & Stubbs, B. Analgesic effects of Alcohol: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of controlled experimental studies in healthy participants. J. Pain18, 499–510 (2017).

World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for Medical Research Involving human subjects. Jama310, 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Lowlands Mojo Concerts B.V. Lowlands Science. 2024. Available: (2024). https://lowlands.nl/ll-science/.Accessed 11 Jan.

de Ronde, A., van Aken, M., de Puit, M. & de Poot, C. A study into fingermarks at activity level on pillowcases. Forensic Sci. Int.295, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.11.027 (2019).

Nas, J. et al. Effect of Face-to-face vs virtual reality training on cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol.5, 328–335 (2020).

Higgins, J. P. T., Chandler, J., Li, T. & Welch, V. A., Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons. (2019).

Franken, A., Keijsers, L., Dijkstra, J. K. & ter Bogt, T. Music preferences, friendship, and externalizing behavior in early adolescence: a SIENA examination of the music marker theory using the SNARE Study. J. Youth Adolesc.46, 1839–1850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0633-4 (2017).

Vlegels, J. & Lievens, J. Music classification, genres, and taste patterns: a ground-up network analysis on the clustering of artist preferences. Poetics. 60, 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.08.004 (2017).

Heidari, S., Babor, T. F., De Castro, P., Tort, S. & Curno, M. Sex and gender equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev.1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6 (2016).

Patanwala, A. E. et al. Psychological and genetic predictors of Pain Tolerance. Clin. Transl Sci.12, 189–195 (2019).

Garza-Villarreal, E. A. et al. Music reduces pain and increases functional mobility in fibromyalgia. Front. Psychol.5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00090 (2014).

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L. & Ky, K. N. Music and spatial task performance. Nature365, 611. https://doi.org/10.1038/365611a0 (1993).

Pauwels, E. K., Volterrani, D., Mariani, G. & Kostkiewics, M. Mozart, music and medicine. Med. Princ Pract.23, 403–412 (2014).

Barlas, T., Sodan, H. N., Avci, S., Cerit, E. T. & Yalcin, M. M. The impact of classical music on anxiety and pain perception during a thyroid fine needle aspiration biopsy. Horm. (Athens). 22, 581–585 (2023).

Choi, E. K., Baek, J., Lee, D. & Kim, D. Y. Effect on music therapy on quality of recovery and postoperative pain after gynecological laparoscopy. Med. (Baltim).102, e33071 (2023).

Fu, V. X. et al. Intraoperative music to promote patient outcome (IMPROMPTU): a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Surg. Res.296, 291–301 (2024).

Hauck, M., Metzner, S., Rohlffs, F., Lorenz, J. & Engel, A. K. The influence of music and music therapy on pain-induced neuronal oscillations measured by magnetencephalography. Pain154 (2013).

Valevicius, D., Lépine Lopez, A., Diushekeeva, A., Lee, A. C. & Roy, M. Emotional responses to favorite and relaxing music predict music-induced hypoalgesia. Front. Pain Res.4https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2023.1210572 (2023).

Soyeux, O. & Marchand, S. A web app-based music intervention reduces experimental thermal pain: a randomized trial on preferred versus least-liked music style. Front. Pain Res. (Lausanne). 3, 1055259 (2022).

Mitchell, L. A., MacDonald, R. A. R. & Brodie, E. E. A comparison of the effects of preferred music, arithmetic and humour on cold pressor pain. Eur. J. Pain. 10, 343–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.005 (2006).

Lu, X., Thompson, W. F., Zhang, L. & Hu, L. Music reduces Pain unpleasantness: evidence from an EEG study. J. Pain Res.12, 3331–3342 (2019).

Bartley, E. J. & Fillingim, R. B. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br. J. Anaesth.111, 52–58 (2013).

Fillingim, R. B. et al. Gender, and Pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J. Pain10, 447–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001 (2009).

Howlin, C., Stapleton, A. & Rooney, B. Tune out pain: Agency and active engagement predict decreases in pain intensity after music listening. PLoS One17, e0271329 (2022).

Staahl, C., Olesen, A. E., Andresen, T., Arendt-Nielsen, L. & Drewes, A. M. Assessing analgesic actions of opioids by experimental pain models in healthy volunteers - an updated review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.68, 149–168 (2009).

Choi, S., Park, J. I., Hong, C. H., Park, S. G. & Park, S. C. Accelerated construction of stress relief music datasets using CNN and the Mel-scaled spectrogram. PLoS One19, e0300607 (2024).

Choi, S. & Park, S. G. Effects of anxiety-related psychological states on music-induced analgesia in cold pressor pain responses. Explore (NY)18, 25–30 (2022).

Becker, A. S. et al. A multidisciplinary approach on music induced-analgesia differentiated by socio-cultural background in healthy volunteers (MOSART): a cross-over randomized controlled trial protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun.39, 101313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2024.101313 (2024).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Report No. 78-92-9189-123-8, (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012). (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Isabel Berger, Melissa Ertman, Julia Peters, Jetske Stoop, Jorrit Verhoeven and Annelotte Versloot for their help in the research team during Lowlands Science. Next, the authors would like to thank Eduard van der Linde on behalf of JBL (Los Angeles, USA) for supporting this study with the contribution of headphones. Moreover, the authors thank Mono Becker, Nicole Hunfeld, Eline Siersma and Antoinette van der Veen-Nikkels for their technical and material support. Finally, the authors would like to thank the crew of Lowlands Science.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the Erasmus MC Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed by E.V.B., A.B., J.S. and M.B. The experiments were performed by A.B., E.V.B., J.S., J.O.G., M.B., M.G., F.V. and R.G. The data were analyzed by A.B. and E.V.B., and the results were critically examined by all authors. E.V.B. and A.B. had a primary role in preparing the manuscript, which was edited by J.S., M.B., J.O.G., M.G., F.V, R.G., J.J. and M.K. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van der Valk Bouman, E.S., Becker, A.S., Schaap, J. et al. The impact of different music genres on pain tolerance: emphasizing the significance of individual music genre preferences. Sci Rep 14, 21798 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72882-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72882-2