Abstract

The flexion relaxation phenomenon (FRP) is characterized by the reduction of paraspinal muscle activity at maximum trunk flexion. FRP is reported to be altered (persistence of spinal muscle activity) in more than half of nonspecific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) patients. Little is known about how the multi-segmental spine affects FRP. The aim of this observational study was to investigate the relationship between FRP and kinematic parameters of the multi-segmental spine in NSCLBP patients. Forty NSCLBP patients and thirty-five asymptomatic participants performed a standing maximal trunk flexion task. Surface electromyography was recorded along the erector spinae longissimus. The kinematics of the spine were assessed using a 3D motion analysis system. The investigated spinal segments were upper thoracic, lower thoracic, thoracolumbar, upper lumbar, lower lumbar, and lumbopelvic. Upper lumbar ROM, anterior sagittal inclination of the upper lumbar relative to the lower lumbar in the upright position, and ROM of the upper lumbar relative to the lower lumbar during full trunk flexion were significantly correlated with the flexion relaxation ratio (Rho 0.42 to 0.58, p < 0.006). The relative position and movement of the upper lumbar segment seem to play an important role in the presence or absence of FRP in NSCLBP patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonspecific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) includes all patients whose chronic low back pain has an unknown etiology, i.e. 80 to 85% of chronic low back pain patients1. This lack of etiological precision leads to various therapeutic interventions and has a limited long-term impact on the disease2,3,4. To improve medical management, the Cochrane Back Review Group proposed defining a NSCLBP classification to deal with the problem of patient heterogeneity5 and to better understand the physiopathology of this disease.

Relevant biomarkers are needed to sub-classify NSCLBP patients. In their systematic review, Moissenet et al.6 reported that the flexion relaxation phenomenon (FRP) was a valid muscular activity biomarker in NSCLBP patients. FRP was described in asymptomatic subjects as a reduction or silence of the myoelectric activity of the erector spinae longissimus muscles during full trunk flexion7. The reduced activity may be explained by a complete relaxation of the spinal extensors at full flexion, with the extension torque supported by the posterior ligaments of the spine8,9. FRP has been reported as altered (decreased or absent) in more than half of NSCLBP patients10 but the physiopathology of this alteration is unclear. Some authors have reported significant relationships between FRP and clinical parameters such as age11, pain12, disability13,14, or kinesiophobia12. Several studies have investigated the relationship between FRP and kinematic parameters of the spine during trunk flexion, such as sagittal range of motion (ROM)11,12,15. In asymptomatic subjects, it has been reported that trunk flexibility plays an important role in the recruitment of trunk extensor muscles during trunk flexion16. Moreover, FRP seems to occur around 80° of trunk flexion in asymptomatic subjects17,18. NSCLBP patients often have reduced trunk ROM and some authors have investigated the relationship between trunk ROM and FRP. For example, Geisser et al. reported a moderate correlation (r = 0.51) between FRP and trunk ROM11. Similarly, Page et al.19 and Watson et al.20 showed a moderate correlation (r = 0.44) between the flexion relaxation ratio (FRR) and lumbar ROM during trunk flexion. However, these studies overlooked regional differences in lumbar spine kinematics (i.e., upper and lower lumbar spine). Indeed, recent studies examining the movement of different lumbar segments (upper and lower) during functional tasks showed different patterns in NCSLBC patients21. To the best of our knowledge, only Ippersiel et al. have studied the relationships between FRP and kinematics of the multi-segmental spine in NSCLBP patients22. However, Ippersiel et al. only studied the inter-joint coordination during the flexion and extension phases without considering the ROM of the different spinal segments.

Besides ROM, other segmental kinematic parameters have been used to classify patients with NSCLBP into different subgroups, such as lumbar spine angles (lower and upper lumbar) in standing posture23,24,25 or sitting trunk flexion26. To our knowledge, the relationships between FRP and these other multi-segmental kinematic parameters of the spine have not yet been studied in NSCLBP patients.

To better understand FRP alteration in NSCLBP patients, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between FRP and multi-segmental kinematic parameters of the spine in NSCLBP patients.

Method

Study design

This cohort study was approved by the local Cantonal Ethics Committee (CER 14–126). All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and later amendments. This study is part of a larger project on identifying subgroups among participants with NSCLBP27. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement (Supplementary data 1).

Participants

The study population consisted of adults suffering from NSCLBP and asymptomatic participants from Geneva (Switzerland). Participants were recruited at outpatient clinics in the Department of Rheumatology and Department of Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine at Geneva University Hospitals. Inclusion criteria for the NSCLBP group were: age between 18 and 60, suffering from NSCLBP, currently experiencing pain for a minimum of three months, and average pain intensity over 3/10 on a visual analog scale during the last two weeks before inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: pain in other parts of the body (except leg pain radiating from the lower back), specific low back condition (e.g., infection, tumor, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome or cauda equina syndrome), pregnancy, body mass index over 30 kg/m2, inability to understand French, neurological or orthopedic deficiencies of the limbs (including the hip joint) that could prevent reliable execution of trunk flexion. In asymptomatic participants, inclusion criteria were as follows: aged between 18 and 60 years and no history of back pain in the last six months.

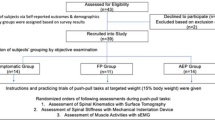

Three groups of participants were defined: a control group of asymptomatic participants with normal FRP and two groups of NSCLBP participants: one with normal FRP and one with altered FRP. Asymptomatic participants with visually altered FRP were excluded from this study.

All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Experimental procedure

The experimental procedure was performed in the Kinesiology Laboratory of the Geneva University Hospitals. Participants completed validated French versions of the Oswestry Disability Index28, the Pain Catastrophizing Scale29, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)30. Current pain was quantified using a visual analog scale. Then they were equipped with a set of sensors (see section Data collection). The participants were then asked to perform two consecutive standing maximal trunk flexions with their legs straight. Only the second trial was used for analysis (the first trial was considered a training trial). This task was divided into four phases (i.e., upright standing, flexion of the trunk, full trunk flexion, and return to upright standing)10. Each phase duration was constrained to last four seconds using rhythmic auditory stimulation.

Data collection

A 12-camera optoelectronic system sampled at 100 Hz (Oqus7+, Qualisys, Sweden) was used to track the three-dimensional (3D) trajectories of a set of eleven cutaneous reflective markers (14 mm). The marker set was composed of four markers on the pelvis (bilateral anterior and posterior superior iliac spines) and seven markers on the spine (spinous process of the vertebrae C7, T6, T10, L1, L3, L5 and S1). Marker placement was achieved by anatomical palpation and remained unchanged during all trials.

An active surface electrode system sampled at 1000 Hz (Trigno Avanti, Delsys Inc, USA), synchronized with the optoelectronic system via the Qualisys data acquisition software (QTM 2020.3, Qualisys, Sweden), was used to collect the surface electromyographic (sEMG) signals collected bilaterally on erector spinae longissimus muscles (at the L1 level of the spinous process). Skin preparation, inter-electrode distance, and electrode location/orientation followed the recommendations of the Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM) project32. The skin preparation consisted of shaving, abrading, and cleaning with alcohol before measurements. Each sensor was maintained using hypoallergenic paper tape to reduce the baseline noise contamination due to movement artefacts (Micropore - Paper Tape, 3 M, USA).

Data processing

The labeling of marker trajectories and sEMG signals was performed using the Qualisys Tracking Manager software (QTM 2020.3, Qualisys, Sweden). Labeled marker trajectories and sEMG signals were exported in the standard C3D file format (https://www.c3d.org) and then imported under Matlab (R2019b, The MathWorks, USA) using the Biomechanics ToolKit (BTK)33 to be processed. Marker trajectories were interpolated when necessary using a reconstruction based on marker inter-correlations obtained from a principal component analysis34, and smoothed using a 4th order Butterworth low pass filter (6 Hz cut-off). sEMG signals were band pass filtered between 20 and 450 Hz (4th order Butterworth filter) to reduce artefacts due to motion and electromagnetic fields.

Computation of parameters

Kinematic parameters

Kinematic parameters were computed as described in Fig. 1, using the processed 3D marker trajectories. Figure 1 illustrates the different kinematic parameters for the first spinal segment C7-T6. Parameters for other spinal segments are available in Supplementary data 2. ROM of the full spine, upper (between the C7-T6 vertebrae) and lower thoracic spine (between the T6-T10 vertebrae), thoracolumbar junction (between the T10-L1 vertebrae), upper (between the L1-L3 vertebrae) and lower lumbar spine (between the L3-S1 vertebrae) were obtained by computing the sagittal angle defined by the spine markers following the procedure proposed by Hidalgo et al.35. The ROM of the pelvis segment (between S1 and the midpoint of the vector connecting the two superior iliac spine markers) was obtained by computing the sagittal angle defined by the pelvis markers following the procedure proposed by the conventional gait model 1.036.

We also studied kinematic parameters between two adjacent spinal segments: the sagittal inclination between two adjacent spinal segments at upright standing and full trunk flexion (Fig. 1), and the ROM between these two parameters (difference of sagittal angles measured at full trunk flexion and upright standing between two adjacent spinal segments).

FRP parameters

The FRR was computed using the Xia method37, which was recently reported to have good sensitivity and reproductibility38 for identifying FRP alterations in NSCLBP patients. According to Gouteron et al.38, the threshold for this FRR to determine whether the patient had an altered or non-altered FRP was 2.45.

FRR was calculated using a custom Matlab software using the following method: maximum RMS of flexion/lowest mean sEMG in 1 s of full flexion. The maximum RMS was the maximum RMS of the filtered sEMG during trunk flexion. The computation of the RMS was performed on the EMG signals using a sliding window of 1 s, moving at a 50 ms step39.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26). Patient characteristics were described as frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and mean (± SD) for quantitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the data distribution’s normality.

Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used to compare clinical and kinematic parameters between the three groups (non-normal distribution). Differences between groups were considered significant at p < 0.05. Post-hoc analyses were performed using the Dunn’s test and a Holm-Bonferroni correction to counter the multiple comparison problem.

Spearman correlations were performed (due to parameters not following a normal distribution) to investigate the relationship between FRR and some clinical or kinematic parameters. Considering the relatively small sample size, only clinical and kinematic variables that were significantly different between participants with altered and non-altered FRP were tested. Results with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant.

Sample size

This study was conducted using an existing cohort, the number of subjects required for which is detailed in the protocol of Rose-Dulcina et al.27.

Results

Participants

In total, 35 healthy and 40 NSCLBP participants were included after excluding 9 NSCLBP (sEMG artefacts) and 7 healthy participants (2 sEMG artefacts and 5 altered FRP). Among the NSCLBP participants, there were 22 patients with altered FRP and 18 with non-altered FRP. The baseline characteristics of the included participants are detailed in Table 1 (at the ESL level). Only mean age and BMI were significantly different between patients with altered FRP and those with non-altered FRP.

Relationships between the FRR and kinematic parameters of multi-segmental spine

Comparison of kinematic parameters of the different spinal segments

The comparison of kinematic parameters of the different spinal segments for LBP patients with altered and non-altered FRP and healthy subjects with non-altered FRP is presented in Table 2. Only mean upper lumbar sagittal ROM, upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal inclination at upright standing and upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal ROM were significantly different between patients with altered FRP and patients with non-altered FRP (letter a in the Table 2).

Figure 2 shows the mean position of each marker at different times of trunk flexion (initial standing position, 20% of flexion, 40% of flexion, 60% of flexion, 80% of flexion, maximum trunk flexion) for patients with altered and non-altered FRP, and asymptomatic participants.

Correlations between FRR and upper lumbar sagittal kinematic parameters

We studied the correlations of the FRR with upper lumbar sagittal ROM, upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal inclination at upright standing, and upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal ROM and FRR in NSCLBP patients. We found moderate correlations between FRR and the three parameters (Fig. 3). The correlation between FRR and sagittal ROM of the upper lumbar spine during trunk flexion was significant and moderate (Rho = 0.47; p = 0.002), the one with upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal inclination at upright standing was negative, significant and moderate (Rho=-0.58; p < 0.001); and the one with upper lumbar/lower lumbar sagittal ROM was significant and moderate (Rho = 0.42; p = 0.006).

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between FRP and multi-segmental kinematic parameters of the spine in NSCLBP patients. Results showed that only the three kinematic parameters of the upper lumbar segment (upper lumbar ROM, sagittal inclination of upper lumbar related to lower lumbar at upright standing, and ROM of upper lumbar related to lower lumbar during full trunk flexion) were significantly different between NSCLBP patients with altered and non-altered FRP. Moreover, the FRR was moderately correlated with these three upper lumbar parameters in NSCLBP patients.

To our knowledge, only Ippersiel et al.22 had already studied the relationship between FRR and a multi-segmental kinematic parameter of the spine, by assessing inter-joint coordination using continuous relative phase analysis. No significant correlation was found between FRR and inter-joint coordination for any of the segments of the spine. Other studies have investigated the role of the upper lumbar segment during trunk flexion in NSCLBP patients, but without considering the relationship of this segment with FRP24,40. For example, Hemming et al. showed that the ROM of the upper lumbar segment was different in two subgroups of patients (Active Extension Pattern and Flexion Pattern)24. The patients with the extension pattern (i.e. patients with pain during activities involving extension) had a decreased ROM of the upper lumbar segment compared to patients with the flexion pattern (i.e. patients with pain during activities involving flexion).

In this study, upper lumbar segment ROM was related to altered FRP. We found that upper lumbar ROM was lower in patients with an altered FRP than in patients with a non-altered FRP. This result is consistent with the pathophysiological hypothesis that lower ROM would inhibit relaxation of the erector spinae longissimus muscle12,15,19. The lumbar spine is a system stabilized by three sub-systems: passive structures (intervertebral disc, vertebrae, ligaments and fascia), active structures (muscles and tendons) and the nervous system41. During full trunk flexion, passive structures such as ligaments stretch, activating stretch mechanoreceptors in passive structures above a certain threshold. This stretch receptor activation inhibits the contraction of spinal extensor muscles42. In patients with NSCLBP, with low ROM, mechanoreceptors do not reach their activation threshold to activate erector spinae longissimus muscle relaxation19. In this study, among the spinal segments, only the upper lumbar ROM was significantly different between the altered and non-altered NSCLBP patients. This suggests that the flexibility of the upper lumbar segment plays a major role in activating the FRP. Moreover, in this study, the ROMs of the spinal segments of NSCLBP patients with altered FRP were lower than those of healthy subjects. These results are consistent with those of Shirado et al.17, where NSCLBP patients with altered FRP had decreased trunk ROM. Thus, it seems important that further studies involving rehabilitation programs should aim to improve ROM in these patients, especially the upper lumbar segment.

Nevertheless, upper lumbar ROM was not the only parameter involved in altered FRP. In this study, FRR was also correlated with the sagittal inclination of the upper lumbar related to the lower lumbar during upright standing. Patients with altered FRP had a decreased sagittal inclination of the upper lumbar related to the lower lumbar during upright standing compared with NSCLBP patients with non-altered FRP. This was in agreement with the results of Dankaerts et al.43 who showed that a subgroup of NSCLBP patients with reduced lordosis in the sitting position had altered FRP during full trunk flexion. Other studies have shown that altered sagittal spino-pelvic alignment, including decreased lordosis, was present in subjects with NSCLBP and not in healthy subjects44,45. Barrey et al.45 argued that the loss of lumbar spinal curvature could be a postural means to decrease the pain related to posterior passive structures (such as posterior facet joints). The lumbar spinal curvature affects the value and location of load on spinal components46. So, a decreased lumbar spinal curvature reduces the load on the posterior facet joints and increases the load on the intervertebral lumbar disc47. However, in this study, it was not possible to determine whether the decreased sagittal inclination (of upper lumbar related to lower lumbar) was present before NSCLBP or a potential compensatory mechanism to avoid pain on the posterior passive structures.

In this study, NSCLBP patients with altered FRP had decreased ROM of the upper lumbar related to the lower lumbar during full trunk flexion. This is consistent with the results of Naserkhaki et al.46. where patients with reduced lumbar curvature during upright standing have decreased trunk curvature during trunk flexion compared to patients with higher lumbar curvature. Furthermore, FRR was moderately correlated with ROM of the upper lumbar in relation to the lower lumbar during full trunk flexion. This suggests that the movement of the upper lumbar segment relative to the lower lumbar segment also plays a role in altered FRP in NSCLBP patients.

In this study, we also investigated kinematic differences between the group of NSCLBP patients with nonaltered FRP and the group of healthy subjects with nonaltered FRP. Only the range of motion of the low lumbar segment was significantly different between the 2 groups. This suggests that low back pain alters the kinematics of the low lumbar segment. This is in accordance with the results of the literature, notably the study by Laird et al.48, which showed a decrease in lumbar ROM in NSCLBP patients. The NSCLBP patient with altered FRP has an altered whole lumbar segment ROM (low and high) compared with the healthy subjects in this study.

This study had some limitations. First, we excluded 11 patients due to artefacts on the EMG signal, which reduced the power of the study. Five patients had a visually altered FRP. As this was a small group, we were unable to perform analyses comparing patients with non-altered FRP and asymptomatic subjects. A future study following more asymptomatic subjects could provide a better understanding of the alteration of the FRP. Secondly, the length of the spinal segments was uneven between the thoracic segments (taking into account more than 4 vertebrae) and the lumbar segments (taking into account 3 vertebrae). By dividing the thoracic part into more segments, specific correlations could appear between the FRR and kinematic parameters of the thoracic segments. Thirdly, the kinematic parameters of successive segments in the same subject were likely to be related. There is a risk of Type I errors being inflated by multiple testing. To mitigate this risk, we have used the Holm-Bonferroni correction in the analysis. Moreover, the included patients had relatively low ODI, HAD, VAS, and kinesiophobia scores, so the results could not be extrapolated to patients with severe disabilities. Alschuler et al.12 showed that kinesiophobic and more painful NSCLBP patients had a more diminished spinal ROM during trunk flexion, and correlated with an altered FRP. With higher levels of kinesiophobia or pain, subjects could limit their spinal ROM to avoid pain and not relax the erector spinae longissimus muscles and thus have an altered FRP. The impact of kinesiophobia and pain on the kinematics of the upper lumbar segment has not yet been studied. Further studies in higher disability patients would be interesting to extend our results to this population. Though the clinical scores in this study were not significantly different, NSCLBP patients with altered FRP were older, which is consistent with the results of Geisser et al.11. Geisser et al. found that older age was associated with both lower levels of muscle relaxation and lower lumbar range of motion. Age could therefore be an uncontrolled confounding factor in this study. In addition, other potential confounders were not taken into account, such as physical activity level. Indeed, in a recent study, participants with a higher level of physical activity showed a more pronounced flexion-relaxation phenomenon49.

Conclusion

Among the spinal kinematic parameters investigated in this study, only upper lumbar kinematic parameters were significantly different between NSCLBP patients with altered and non-altered FRP. Indeed, upper lumbar ROM, sagittal inclination of the upper lumbar related to the lower lumbar during upright standing, and upper lumbar ROM related to lower lumbar ROM during full trunk flexion were significantly lower in NSCLBP patients with altered FRP compared to NSCLBP patients with non-altered FRP. Moreover, these three upper lumbar parameters were moderately correlated with FRR. Upper lumbar segment position and movement seem to play an important role in the presence or absence of FRP in NSCLBP patients.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Kinesiology Laboratory of Geneva University Hospitals.

References

Airaksinen, O. et al. COST B13 Working Group on guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur. Spine J.15(Suppl 2), S192–S300 (2006).

Assendelft, W. J., Morton, S. C., Yu, E. I., Suttorp, M. J. & Shekelle, P. G. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1), CD000447 (2004).

Ostelo, R. W. et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1), CD002014 (2005).

Furlan, A. D., Giraldo, M., Baskwill, A., Irvin, E. & Imamura, M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (9), CD001929 (2015).

Bouter, L. M., Pennick, V. & Bombardier, C. Editorial Board of the Back Review Group. Cochrane back review group. Spine. 28(12), 1215–1218 (2003).

Moissenet, F., Rose-Dulcina, K., Armand, S. & Genevay, S. A systematic review of movement and muscular activity biomarkers to discriminate non-specific chronic low back pain patients from an asymptomatic population. Sci. Rep.11(1), 5850 (2021).

Floyd, W. F. & Silver, P. H. The function of the erectores spinae muscles in certain movements and postures in man. J. Physiol.129(1), 184–203 (1955).

Schultz, A. B., Haderspeck-Grib, K., Sinkora, G. & Warwick, D. N. Quantitative studies of the flexion-relaxation phenomenon in the back muscles. J. Orthop. Res.3(2), 189–197 (1985).

Gupta, A. Analyses of myo-electrical silence of erectors spinae. J. Biomech.34(4), 491–496 (2001).

Gouteron, A. et al. The flexion relaxation phenomenon in nonspecific chronic low back pain: prevalence, reproducibility and flexion-extension ratios. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J.31(1), 136–151 (2022).

Geisser, M. E., Haig, A. J., Wallbom, A. S. & Wiggert, E. A. Pain-related fear, lumbar flexion, and dynamic EMG among persons with chronic musculoskeletal low back pain. Clin. J. Pain. 20(2), 61–69 (2004).

Alschuler, K. N., Neblett, R., Wiggert, E., Haig, A. J. & Geisser, M. E. Flexion-relaxation and clinical features associated with chronic low back pain: a comparison of different methods of quantifying flexion-relaxation. Clin. J. Pain. 25(9), 760–766 (2009).

Dubois, J. D., Piché, M., Cantin, V. & Descarreaux, M. Effect of experimental low back pain on neuromuscular control of the trunk in healthy volunteers and patients with chronic low back pain. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.21(5), 774–781 (2011).

Ritvanen, T., Zaproudina, N., Nissen, M., Leinonen, V. & Hänninen, O. Dynamic surface electromyographic responses in chronic low back pain treated by traditional bone setting and conventional physical therapy. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther.30(1), 31–37 (2007).

Rose-Dulcina, K., Genevay, S., Dominguez, D., Armand, S. & Vuillerme, N. Flexion-relaxation ratio asymmetry and its relation with trunk lateral ROM in individuals with and without chronic nonspecific low back Pain. Spine. 45(1), E1–E9 (2020).

Hashemirad, F., Talebian, S., Hatef, B. & Kahlaee, A. H. The relationship between flexibility and EMG activity pattern of the erector spinae muscles during trunk flexion-extension. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.19(5), 746–753 (2009).

Shirado, O., Ito, T., Kaneda, K. & Strax, T. E. Flexion-relaxation phenomenon in the back muscles. A comparative study between healthy subjects and patients with chronic low back pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 74(2), 139–144 (1995).

Shin, G., Shu, Y., Li, Z., Jiang, Z. & Mirka, G. Influence of knee angle and individual flexibility on the flexion-relaxation response of the low back musculature. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.14(4), 485–494 (2004).

Pagé, I., Marchand, A. A., Nougarou, F., O’Shaughnessy, J. & Descarreaux, M. Neuromechanical responses after biofeedback training in participants with chronic low back pain: an experimental cohort study. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther.38(7), 449–457 (2015).

Watson, P. J., Booker, C. K., Main, C. J. & Chen, A. C. Surface electromyography in the identification of chronic low back pain patients: the development of the flexion relaxation ratio. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol Avon). 12(3), 165–171 (1997).

Dankaerts, W., O’Sullivan, P., Burnett, A. & Straker, L. Altered patterns of superficial trunk muscle activation during sitting in nonspecific chronic low back pain patients: importance of subclassification. Spine31(17) (2006).

Ippersiel, P. et al. Inter-joint coordination and the flexion-relaxation phenomenon among adults with low back pain during bending. Gait Posture. 85, 164–170 (2021).

Mitchell, T., O’Sullivan, P. B., Burnett, A. F., Straker, L. & Smith, A. Regional differences in lumbar spinal posture and the influence of low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 9, 152 (2008).

Hemming, R., Sheeran, L., van Deursen, R. & Sparkes, V. Non-specific chronic low back pain: differences in spinal kinematics in subgroups during functional tasks. Eur. Spine J.27(1), 163–170 (2018).

O’Sullivan, P. B. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Man. Ther.5(1), 2–12 (2000).

Dankaerts, W., O’Sullivan, P., Burnett, A. & Straker, L. Differences in sitting postures are associated with nonspecific chronic low back pain disorders when patients are subclassified. Spine. 31(6), 698–704 (2006).

Rose-Dulcina, K. et al. Identifying subgroups of patients with chronic nonspecific low back Pain based on a Multifactorial Approach: Protocol for a prospective study. JMIR Res. Protoc.7(4), e104 (2018).

Vogler, D., Paillex, R., Norberg, M., de Goumoëns, P. & Cabri, J. Validation transculturelle de l’Oswestry disability index en français [Cross-cultural validation of the Oswestry disability index in French]. Ann. Readapt Med. Phys.51(5), 379–385 (2008).

French, D. J. et al. L’Échelle de dramatisation face à La Douleur PCS-CF. Adaptation canadienne en langue française de l’échelle «Pain Catastrophizing Scale». Can. J. Behav. Sci.37, 181–192 (2005).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand.67(6), 361–370 (1983).

van Jan, S. S. Color Atlas of Skeletal Landmark Definitions: Guidelines for Reproducible Manual and Virtual Palpations (Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2007).

Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst-Klug, C. & Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.10(5), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1050-6411(00)00027-4 (2000).

Barre, A., Armand, S., Biomechanical & ToolKit Open-source framework to visualize and process biomechanical data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed.114(1), 80–87 (2014).

Gløersen, Ø. & Federolf, P. Predicting missing marker trajectories in human Motion Data using marker intercorrelations. PloS ONE. 11(3), e0152616 (2016).

Hidalgo, B., Gilliaux, M., Poncin, W. & Detrembleur, C. Reliability and validity of a kinematic spine model during active trunk movement in healthy subjects and patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Rehabil. Med. 44(9), 756–763 (2012).

Leboeuf, F. et al. The conventional gait model, an open-source implementation that reproduces the past but prepares for the future. Gait Post. 69, 235–241 (2019).

Xia, T. et al. Association of lumbar spine stiffness and flexion-relaxation phenomenon with patient-reported outcomes in adults with chronic low back pain - a single-arm clinical trial investigating the effects of thrust spinal manipulation. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.17(1), 303 (2017).

Gouteron, A. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the flexion and extension relaxation ratios to identify altered paraspinal muscles’ flexion relaxation phenomenon in nonspecific chronic low back pain patients. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.68, 102740 (2023).

Farina, D. & Merletti, R. Comparison of algorithms for estimation of EMG variables during voluntary isometric contractions. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.10(5), 337–349 (2000).

Gombatto, S. P. et al. Differences in kinematics of the lumbar spine and lower extremities between people with and without low back pain during the down phase of a pick up task, an observational study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract.28, 25–31 (2017).

Panjabi, M. M. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J. Spinal Disord. 5(4), 383–397 (1992).

Holm, S., Indahl, A. & Solomonow, M. Sensorimotor control of the spine. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.12(3), 219–234 (2002).

Dankaerts, W. et al. Discriminating healthy controls and two clinical subgroups of nonspecific chronic low back pain patients using trunk muscle activation and lumbosacral kinematics of postures and movements: a statistical classification model. Spine. 34(15), 1610–1618 (2009).

Chaléat-Valayer, E. et al. Sagittal spino-pelvic alignment in chronic low back pain. Eur. Spine J.20 Suppl 5, 634–640 (2011).

Barrey, C., Jund, J., Noseda, O. & Roussouly, P. Sagittal balance of the pelvis-spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases. A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur. Spine J.16(9), 1459–1467 (2007).

Naserkhaki, S., Jaremko, J. L. & El-Rich, M. Effects of inter-individual lumbar spine geometry variation on load-sharing: geometrically personalized finite element study. J. Biomech.49(13), 2909–2917 (2016).

Roussouly, P. & Pinheiro-Franco, J. L. Biomechanical analysis of the spino-pelvic organization and adaptation in pathology. Eur. Spine J.20(Suppl 5), 609–618 (2011).

Laird, R. A., Gilbert, J., Kent, P. & Keating, J. L. Comparing lumbo-pelvic kinematics in people with and without back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 15, 229 (2014).

Li, Y., Pei, J., Li, C., Wu, F. & Tao, Y. The association between different physical activity levels and flexion-relaxation phenomenon in women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 21(1), 62 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Suzanne Rankin for her help during the preparation of the manuscript.We acknowledge the entire staff of the Kinesiology Laboratory of Geneva University Hospitals for their support.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G., S.A., D.L. and S.G. conceived and designed the study. A.G., A.T.F, F.M. and K.R.D analyzed and produced the data and results. A.G., S.A, D.L, F.M first drafed the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript to bring important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gouteron, A., Moissenet, F., Tabard-Fougère, A. et al. Relationship between the flexion relaxation phenomenon and kinematics of the multi-segmental spine in nonspecific chronic low back pain patients. Sci Rep 14, 24335 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72924-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72924-9