Abstract

This study presents an approach that integrates compressed sensing technology with two-dimensional hyperchaotic coupled Fourier oscillator systems (2D-HCFOS) to address the challenge of slow encryption speeds in agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The primary challenge in enhancing encryption speed lies in the limited capacity inherent in traditional chaotic-based systems and the computational complexity of their processes. The 2D-HCFOS utilizes a complex two-dimensional hybrid chaotic system, which significantly enhances the security of agricultural UAV image data. Notably, the image encryption process is performed on a personal computer connected to the drone, ensuring efficient processing. By integrating advanced Fourier series and nonlinear coupled oscillators, the model surpasses existing chaotic-based methods, improving both the pseudo-randomness and robustness of encryption. Additionally, incorporating Bonouille functions into the discrete cosine transform (DCT) domain results in a sparser measurement matrix, which is essential for efficient encryption on personal computers. The effectiveness of 2D-HCFOS in securely encrypting agricultural drone images has been rigorously validated through simulations and analytical evaluations using sophisticated row, rotation, and matrix encryption techniques. The improved security performance is further verified by comparative analysis. Compared with other models, the Lyapunov index of 2D-HCFOS is 15.1039, and the sample entropy is 2.4987, indicating that it possesses superior chaotic performance and encryption reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In their influential 2019 article, “A Review of Precision Agriculture Applications Based on UAVs,” Tsouros, Bibi, and Sarigiannidis underscored the transformative role of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in advancing precision agriculture, particularly emphasizing the critical importance of image security1. As UAVs increasingly rely on advanced imaging technologies, the protection of image data has become a central concern. Transmitting these images to cloud services introduces significant risks of information leakage for agricultural drones2, as demonstrated by statistical data. These security vulnerabilities have led to substantial economic repercussions, reshaping the global economic landscape through escalating costs and rising cyber insurance claims3,4,5.

In addressing security and privacy issues within cyber-physical social systems (CPSS), Song et al.6 proposed a novel approach centred around delivering resource-rich and personalized services. The recent study by Erkan et al.7 on the two-dimensional Schaffer map’s dynamic performance confirmed its hyperchaotic behaviour, surpassing traditional chaotic models. Jiang et al.8 utilized two-dimensional hyperchaotic mapping for key sequence generation, which is crucial in scrambling and encrypting image pixels. However, their approach highlighted limitations regarding computational complexity and scope of application. Addressing these shortcomings, Gao et al.9 introduced an enhanced two-dimensional discrete hyperchaotic system, exhibiting remarkable ergodicity, unpredictability, and a more comprehensive chaotic range, offering improvements over the previous model. Furthermore, Lai et al.10 advanced logistic mapping with discrete memristors, augmenting the mapping’s intricate dynamics and unpredictability. Ustone et al.11 devised a groundbreaking two-dimensional infinite fold graph for image encryption using advanced modulation techniques. However, these models exhibit constraints in their chaotic breadth and fail to ensure optimal confidentiality. Moreover, traditional image encryption processes involving complex computations are not suited for real-time and rapid encryption, a necessity for the Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled devices and networks, like smart devices, edge, and cloud servers.

To address the challenges of real-time image security for agricultural drones, a novel method is proposed, as illustrated in Fig. 1:

-

1.

A new two-dimensional hyperchaos model, derived from Fourier series and nonlinear coupled oscillator models, has been developed. This model demonstrates superior chaotic performance compared to previous models, featuring a Lyapunov exponent of 15.1039 and an extensive control parameter range reaching 600.

-

2.

The integration of the Bonouille function within the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) domain produces a sparser measurement matrix. By leveraging the DCT’s energy concentration properties alongside the randomness introduced by the Bonouille function, this approach enables more effective compressed sensing sampling. The resulting image compression and encryption processes significantly reduce image size and storage requirements while also lowering hardware demands. Importantly, the encryption is performed on a personal computer connected to the drone, which enhances the speed and security of the image encryption process, ensuring that sensitive agricultural data is safeguarded in real-time.

-

3.

A robust security scheme for image protection in agricultural UAVs has been developed, demonstrating promising results in experimental settings and offering a novel solution to the image security challenges in agricultural UAV applications.

Model building and methods

This section introduces the two-dimensional hyperchaotic coupling of the Fourier series with the nonlinear coupled oscillator models (2D-HCFOS), which are pivotal concepts in physics and mathematics for analyzing periodic signals and the dynamics of complex systems. Here, we provide a succinct overview of these models, discussing their integration and the mathematical basis for their coupling.

Fourier series

The Fourier series decomposes any periodic function or signal into a combination of sine and cosine functions. For a periodic function \(f(t)\) with a period \(T\), it is expressed as:

where \(\omega _0 = \frac{2\pi }{T}\) represents the fundamental angular frequency. The Fourier coefficients \(a_n\) and \(b_n\) are determined by:

Nonlinear coupled oscillator model

This model illustrates a system where oscillators interact through nonlinear mechanisms. In a basic configuration of two oscillators, the dynamics are formulated as:

Here, \(x\) and \(y\) denote the displacements of the oscillators, \(\omega _x\) and \(\omega _y\) their natural frequencies, and \(f(x, y)\) and \(g(x, y)\) the nonlinear coupling functions.

Two-dimensional hyperchaotic coupling

The integration of nonlinear functions through \(sin(\text {a} \cdot x_i) + b \cdot sin(y_i \cdot x_i)\) and \(sin(c \cdot y_i) + d \cdot sin(x_i \cdot y_i)\) introduces nonlinear coupling. The incorporation of the Fourier series using \(e \cdot cos(2 \cdot \pi \cdot x_i)\) and \(e \cdot cos(2 \cdot \pi \cdot y_i)\) adds a periodic driving force to the system. Here, the cosine functions represent the periodic influences on the system.

To simulate real-world randomness and increase complexity, random perturbations are added by \(noise\_level \cdot randn()\). The model’s update rules are formulated as follows:

The chaotic performance test of two-dimensional hyperchaotic coupled Fourier oscillation system

Bifurcation diagram and phase diagram

The dynamic behavior of a chaotic system can be effectively analyzed using bifurcation and phase diagrams, which also allow visualization of the system’s trajectory and ergodic characteristics. The bifurcation diagram displays the distribution of the system’s output across a specific parameter range within the phase space. In contrast, a phase diagram plots the values of two or more state variables, emphasizing their interrelationships. Figures 2 and 3 present a two-dimensional phase diagram of a 2D-HCFOS system and the bifurcation diagrams of variables \(x\) and \(y\). The phase diagram reveals that the points form a rhomboid-like trajectory between the \(x\) and \(y\) axes, with several high-density regions. When the parameter \(a\) exceeds a certain threshold, densely packed bifurcation points appear in the diagram, indicating that the system has entered a chaotic regime. At this stage, the system’s state is no longer characterized by a single or a few values but by a quasi-random distribution. These diagrams illustrate that chaotic trajectories are widely distributed throughout the phase space, with no periodic windows over a broad parameter range. The chaotic output values are not concentrated at the phase space’s edges but are uniformly distributed, demonstrating that the 2D-HCFOS system exhibits strong chaotic behavior. This characteristic enhances the system’s security, making it particularly suitable for image encryption applications.

Lyapunov exponent performance test

Ott et al.12 introduced the application of the Lyapunov exponent in chaotic systems. The Lyapunov exponent quantifies the average exponential divergence rate of neighboring trajectories in a system’s phase space, serving as a crucial metric for evaluating the intensity of chaotic behavior. While a single Lyapunov exponent provides information about a specific direction, using multiple Lyapunov exponents offers a more comprehensive description of the system’s characteristics. The state trajectories of chaotic systems often exhibit different dynamic behaviors in various directions. Analyzing multiple Lyapunov exponents captures the evolution rates in these different directions, revealing the system’s diversity and complexity. Based on this concept, we utilize two Lyapunov exponents to determine the hyperchaotic nature of our system.

The standard method to calculate the Lyapunov exponent, as introduced by Benettin et al.13, involves the following steps:

-

1.

Set initial conditions \({\textbf{x}}_0\) and a small perturbation \(\delta {\textbf{x}}_0\).

-

2.

Use a numerical method, such as the Runge-Kutta method, to compute the system’s trajectories:

$$\begin{aligned} {\textbf{x}}(t) \quad \text {and} \quad {\textbf{x}}(t) + \delta {\textbf{x}}(t), \end{aligned}$$(8)where \({\textbf{x}}(t)\) and \({\textbf{x}}(t) + \delta {\textbf{x}}(t)\) are the solutions at time t and the perturbed solution, respectively.

-

3.

Calculate the variation in distance between nearby orbits

$$\begin{aligned} \delta (t) = \Vert \delta {\textbf{x}}(t)\Vert , \end{aligned}$$(9) -

4.

Estimate the Lyapunov exponent:

$$\begin{aligned} \lambda = \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty } \frac{1}{t} \log \left( \frac{\delta (t)}{\delta (0)} \right) , \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(\delta (0) = \Vert \delta {\textbf{x}}_0\Vert\) is the initial size of the perturbation.

In this study, the maximum value of the Lyapunov exponent was determined to be 15.103, as shown in Fig. 4. This indicates that the system is highly sensitive to variations in parameters \(a\) and \(b\). The significant changes in LE1 and LE2 suggest that the system can abruptly transition from a stable state to a chaotic state under specific parameter values. Additionally, we compared our model with those of other studies. As demonstrated in Table 1 and 2, our 2D-HCFOS model outperforms other models in terms of chaotic behavior. This enhanced chaotic behavior significantly bolsters the security of agricultural drone image transmission, providing robust protection against potential cyber threats.

A hyperchaotic system is typically defined by having multiple positive Lyapunov exponents, indicating exponential divergence of trajectories in multiple directions, thus exhibiting higher-dimensional complexity and unpredictability. In our system, the presence of two positive Lyapunov exponents confirms its hyperchaotic nature.

0-1 test

The 0-1 test is a chaotic index for evaluating the rate of series expansion in nonlinear dynamic systems. This test can determine the frequency of fixed results in arbitrary time series of dynamic systems based on two-dimensional Euclidean groups. Suppose the test entry is a one-dimensional chaotic sequence \(\phi ({{\textbf {a}}})\) used to form a system.

where \(c \in (0, 2\pi )\) is a constant. The mean sequence-mean square error is described as:

The expansion rate is given by

K can be approximately 0 for non-dynamic systems and close to 1 for complex systems. A completely chaotic system generates a sequence with \(K = 1\). As shown in Fig. 5, the test results indicate that the system exhibits strong chaos across most control parameters \(a\) (where the \(K\) value is close to 1). However, within specific parameter ranges, the chaotic nature of the system diminishes, and the value of \(K\) fluctuates around 1. This observation provides compelling evidence of the model’s robust chaotic behavior, which is consistent with the expected characteristics of highly chaotic systems.

Sample entropy test

Sample entropy (SE) is a mathematical index used to evaluate the self-similarity of chaotic sequences in dynamic systems. It quantitatively defines the complexity generated by dynamic systems. Consider a model with size n, denoted as \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \cdots , x_n\}\), and let \(x_m(i) = \{x_i, x_{i+1}, \cdots , x_{i+m-1}\}\) represent a template vector of size m. The SE is calculated as follows:

Here, \(r\) represents the maximum tolerance, and \(A\) is a template vector defined as \((x_m(i), x_m(j))\), with \(d[x_{m+1}(i), x_{m+1}(j)] < r\). Similarly, \(B\) is another template vector defined as \((x_m(i), x_m(j))\), satisfying \(d[x_m(i), x_m(j)] < r\). These calculations employ Chebyshev distances. A higher sample entropy (SE) indicates lower regularity and, therefore, greater randomness in the dynamic system. As shown in Fig. 6, when the values of \(a\) and \(b\) range from 0 to 100, the sample entropy peaks at 2.4987, strongly reflecting the system’s complexity. The analysis of this graph indicates that the chaotic performance of the system is highly sensitive to changes in parameters \(a\) and \(b\). Regions with high sample entropy correspond to greater chaos, whereas regions with low entropy suggest a more orderly system. Through comprehensive comparative analysis, as shown in Tables 1 and 2, our model demonstrates superior chaotic performance compared to competing models, highlighting its enhanced capability to accurately characterize complex dynamic systems.

Correlation dimension

The occupied space dimension of the time series is the fractal dimension, expressed as CD21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. CD is used to distinguish whether a sequence is deterministically chaotic or truly random. It has been utilized in various applications to evaluate time series data.

For random systems, the fractal dimension equals the phase space dimension. For completely chaotic systems, the fractal dimension is smaller and typically not an integer. If the CD of a time series is greater than 0, the system is considered chaotic. Additionally, a larger CD indicates a higher spatial dimension occupied by the sequence. CD is calculated as follows:

where

Here, \(1\) and \(R\) are index functions and similarity radii, respectively.

where the minimum and maximum radial values are \(r_{\min }\) and \(r_{\max }\), respectively, and \(N\) is the number of points. CD can be defined as the slope of \(CD(R)\) with respect to \(R\). Table 2 compares recently reported CD scores, with average CD values also listed. The 2D-HCFOS method is superior to existing methods because it has the best chaos performance with an average CD of 2.6832.

Agricultural drone image protection experimental plan

Experimental data

The experiment was conducted on a PC equipped with an Intel Core i7-10750H CPU, operating at a frequency of 2.60 GHz and with 16 GB of RAM, using MATLAB R2022a. The dataset used in this study comprises more than 6,000 high-resolution plane images (\(1024 \times 1024\) pixels) captured by agricultural drones. These images primarily depict agricultural landscapes in Europe and Canada, totaling approximately 4,000 images. An additional test dataset includes around 2,000 images of agricultural scenes from North America (excluding Canada), Asia, Oceania, and Africa, as referenced in29. To rigorously assess the robustness and adaptability of the algorithm in real-world agricultural scenarios, we selected a comprehensive and diverse set of agricultural drone images. The experiments confirm the algorithm’s effectiveness for securely encrypting and compressing the plane images from the agricultural UAV database. This ensures that sensitive agricultural data is protected and efficiently managed within precision agriculture applications.

Bonouille-DCT compressed sensing methodology

The Bonouille-DCT compressed sensing method assumes that the image vector \({{\textbf {s}}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^m\) is sparse in a specific transform domain, particularly the discrete cosine transform (DCT) domain. This sparsity implies that most components of \({{\textbf {s}}}\) are zero, resulting in a sparse representation where only k elements are non-zero.

This method employs a discrete cosine transform and a sparse Bernoulli matrix function to construct a measurement matrix \(\Phi \in {\mathbb {R}}^{K \times m}\). The matrix \(\Phi\) is designed as a sparse Bernoulli matrix optimized for the DCT domain. Here, K represents the total number of measurements, and m represents the image size after being flattened following the DCT.

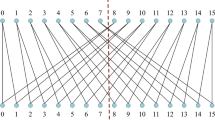

The processing pipeline structure for each image channel is as follows:

-

1.

Convert the image channel to a one-dimensional vector \({{\textbf {f}}}\).

-

2.

Apply the DCT to \({{\textbf {f}}}\), resulting in \({{\textbf {F}}} = \text {DCT}({{\textbf {f}}})\).

-

3.

Perform a linear measurement of \({{\textbf {F}}}\) using the matrix \(\Phi\), yielding the compressed sensing measurement \({{\textbf {y}}} = \Phi {{\textbf {F}}}\).

The optimization problem is defined as \(P_0^{1D}\) and \(P_0^{2D}\), formalized by the equation:

where \(|{{\textbf {s}}}|_0\) quantifies the number of non-zero elements in \({{\textbf {s}}}\).

In the experimental framework, \({{\textbf {y}}}\) is the result of the measurement process, \({{\textbf {s}}}\) is the image vector after the DCT transformation, and \(\Phi\) is the constructed Bernoulli measurement matrix. The experimental design adheres to the formula \({{\textbf {y}}} = \Phi {{\textbf {F}}}\), where \({{\textbf {F}}}\) is the image in the DCT domain, \(\Phi\) is the Bernoulli matrix, and \({{\textbf {y}}}\) is the final compressed sensing measurement. This process includes both compression and subsequent encryption, integrating these steps to enhance security, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

An efficient encryption scheme

This study presents an advanced image encryption algorithm designed to securely transmit images captured by uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs). Figure 7 details the algorithm, which employs a two-stage encryption process combining intricate chaotic dynamics, the Arnold transformation, and bitwise exclusive OR (XOR) operations to achieve enhanced security. The encryption procedure encompasses several meticulously defined steps, outlined as follows:

Step 1: Key generation

In the initial phase, the algorithm utilizes a hash function to generate a 256-bit key. To produce a binary sequence, this process involves two primary keys, key1 and key2. Differences between these keys are encoded as “1” and similarities as “0”, effectively expanding the key space. This expanded space enhances security against brute force attacks, providing a robust foundation for the subsequent encryption stages.

Step 2: Chaotic system iteration

The encryption process progresses with the activation of two independent chaotic systems, initiated using the first 32 bits of the synthesized key. These systems undergo a series of normalization and iterative computations, integrating nonlinear dynamics, cyclical forces, and stochastic disturbances. The result of these computations is the generation of two distinct chaotic sequences, denoted as \(x\) and \(y\).

Step 3: Arnold scrambling

Next, Arnold’s transformation is applied using the end parameters of the chaotic sequences. This step strategically alters the pixel array of the image, significantly enhancing its complexity and thereby bolstering the robustness of the encryption.

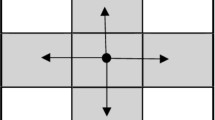

Step 4: Image rotation

Utilizing the chaotic sequences \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\), the algorithm calculates the displacement for each row and column of the image. The parity of these displacements determines the direction of the rotational shift-either left or right, up or down-resulting in a transformed spatial configuration of the image.

Step 5: XOR encryption

In the final step, the scrambled image undergoes an XOR operation with the chaotic sequence \(m\). This linearizes and encrypts the image, significantly obscuring the pixel data and further fortifying the overall security.

This innovative algorithm offers robust protection for UAV images during transmission. It is versatile across various image formats and resilient to the diverse operational conditions inherent in UAV usage, demonstrating comprehensive encryption efficacy.

An efficient decryption scheme

The encrypted image must be decrypted to recover the original image, following the process illustrated in Fig. 8.

Step 1: Key recovery

Using the same hash function as in the encryption process, split the 256-bit binary key sequence into two 128-bit sub-keys. Each sub-key is then divided into two 64-bit parts, corresponding to the original master keys key1 and key2.

Step 2: Chaotic system backward iteration

Use the first 32 bits of the recovered master key to initialize two independent chaotic systems in the same manner as the encryption process. Iterate backward through the chaotic systems to generate chaotic sequences \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) identical to those used in the encryption process. The generation of chaotic sequences must strictly follow the parameters and iteration counts used in the encryption process to ensure consistency.

Step 3: XOR decryption

Perform a bitwise XOR operation on the encrypted image using the chaotic sequence \(m\). Since the XOR operation is reversible, using the same chaotic sequence \(m\) allows the restoration of the image prior to XOR encryption.

Step 4: Image reverse rotation

Utilize chaotic sequences \(x\), \(y\) to compute row and column displacements in the reverse direction of the encryption process. Based on the parity of the displacements, rotate the image in the opposite direction (right/left, down/up) to restore the original spatial configuration. Rotation operations must strictly adhere to the shift amounts and rotation directions used in the encryption process to ensure correct restoration of the image’s spatial relationships.

Step 5: Arnold inverse transformation

Apply the Arnold inverse transformation to the image using the final parameters of the chaotic sequence. The Arnold transformation is a reversible scrambling operation; applying the Arnold inverse transformation iteratively restores the original pixel arrangement. The number of iterations must match the Arnold scrambling count used in the encryption process to fully restore the original pixel arrangement.

Step 6: Compressive sensing reconstruction

Convert the decrypted image into a one-dimensional vector \(f'\). Apply the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to \(f'\) to obtain \(F' = \text {DCT}(f')\). Using the Bernoulli matrix \(\Phi\) employed in the encryption process, solve the optimization problem:

where \(y\) represents the encrypted measurement values and \(s\) is the sparse representation of \(F'\) in the DCT domain. Use the compressive sensing reconstruction algorithm, Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP), to recover the non-zero elements of \(s\) from \(y\). Convert the recovered \(s\) back to the DCT coefficients \(F\) of the image and apply the inverse DCT to obtain the reconstructed original image \(f\).

Encryption performance and security analysis

This section provides a comprehensive encryption and performance analysis of three distinct images from the dataset25, as shown in Fig. 9. Each image has a resolution of 1024 x 1024 pixels, with varied plant shapes and colors, ensuring that the algorithm is thoroughly tested across different scenarios. Detailed evaluations, including rigorous comparative experiments, demonstrate that the encryption scheme, specifically designed for agricultural drone imagery, offers significantly enhanced effectiveness. Furthermore, the encryption strength is assessed, and the algorithm’s efficiency and adaptability across various image scenarios are examined. The results confirm the algorithm’s suitability for protecting sensitive aerial images in diverse agricultural settings.

Key sensitivity analysis

In the field of image encryption, the importance of key space size and sensitivity is crucial. Our encryption scheme employs robust 256-bit keys, equivalent to a key space of \(2^{256}\), effectively making brute force attacks infeasible. Key sensitivity, a critical factor in determining encryption strength, was evaluated using the Number of Pixels Change Rate (NPCR) and the Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI).

where \(E1\) and \(E2\) are two encrypted images, and \(D(i,j)\) is defined as follows:

Analysis results showed that NPCR was 99.6067% and UACI was 33.4556%, while the ideal values for UACI and NPCR are 33.4635% and 99.6094%, respectively30. These values indicate the high sensitivity of the system. A review of the data in Table 3 shows that these NPCR and UACI indicators are very close to the theoretical optimal values. This proximity emphasizes the robustness of the algorithm, especially in protecting against plaintext and differential attacks.

Table 4 presents the results of experiments with different standard cryptographic images using various existing methods, including ours. These results show that our method is highly sensitive to bit modifications in ordinary images, thereby making differential attacks ineffective.

Plaintext sensitivity analysis

Assessing a cryptosystem’s sensitivity to minute changes in plaintext is imperative for defending against Chosen-Plaintext Attacks (CPA). In our study, this evaluation involves subtly altering a single pixel in each of three distinct images according to the following equation:

This modification ensures minimal yet significant change. The altered images undergo encryption, and the system’s response is measured through subsequent Number of Pixels Change Rate (NPCR) and Uniform Average Change Intensity (UACI) calculations. These calculations demonstrate the cryptosystem’s high resilience, with repeated trials consistently confirming robust defence against differential attacks.

Robustness testing

Encryption algorithms frequently face challenges such as pixel loss due to interception during image handling or natural degradation. The primary objective of these algorithms is to efficiently reconstruct partially damaged images, thereby minimizing quality degradation. In our experiment, this resilience was evaluated by deliberately cropping the encrypted images to various extents. As shown in Fig. 10, although the sharpness of the decrypted image decreases with increased cropping, the overall readability remains largely unaffected, and the plant-related colors and shapes are still recognizable. This demonstrates the algorithm’s strong resistance to cropping and its robustness in preserving critical image details.

Correlation coefficient, SSIM, and PSNR analysis

In evaluating encrypted image quality, we focus on three key metrics: the correlation coefficient (CC), the structural similarity index (SSIM)32, and the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR)33. The correlation coefficient (CC), specifically its horizontal (\(C_H\)), vertical (\(C_V\)), and diagonal (\(C_D\)) components, measures the relationship between adjacent pixels in an image, indicating the level of similarity between them. The structural similarity index (SSIM) quantifies image quality degradation caused by processing such as data compression or transmission, providing a perceptual measure of image fidelity. The peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) compares the maximum possible pixel value to the mean squared error, assessing the quality of the reconstructed image.

The formula for calculating the correlation coefficient is as follows:

The formula for calculating the structural similarity index (SSIM) is:

The formula for calculating the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) is:

Here, MAX represents the maximum possible pixel value in the image, and MSE denotes the mean squared error.

Correlation Coefficient, SSIM, and PSNR analyses are performed in section An efficient encryption scheme of the article. These metrics are detailed in Tables 5 and 6. An effective encryption algorithm is characterized by a PSNR value below 10, indicating high-quality encryption. Moreover, an SSIM value approaching zero indicates optimal encryption, demonstrating strong security performance in our scheme.

Table 4 presents the results of experiments with different standard cryptographic images using various existing methods, including ours. These results show that our method is highly sensitive to bit modifications in ordinary images, thereby making differential attacks ineffective.

For the consistency of the histogram of the encrypted image, as shown in Fig. 11(1)–(6), the effectiveness of the encryption algorithm is demonstrated by the significant changes in row correlation across image channels before and after encryption. This substantial reduction in predictability and correlation serves as key evidence of the encryption algorithm’s success in disrupting the original image structure and eliminating pixel correlation. The method ensures a consistent histogram for agricultural drone images, irrespective of their original intensity distribution. This consistency significantly enhances the security of information systems used in agricultural applications, protecting sensitive data from potential statistical analysis attacks.

Floating frequency testing

Floating frequency analysis evaluates the uniformity of encryption across the rows and columns of an image22, identifying weak encryption areas. The process involves the following steps:

Window selection: sequential 256-element windows are selected along each row and column.

Element comparison: the number of unique elements within each window is determined.

Row and column floating frequencies (RFF and CFF): frequencies of unique elements in windows along rows (RFF) and columns (CFF) are calculated.

Mean calculation and visualization: mean RFF and CFF values across all windows provide insights into encryption uniformity. Visual plots highlight variations in encryption effectiveness.

This method identifies areas where encryption may be less effective, aiding in targeted improvements. Fig. 12 shows the RFF and CFF results for experimental images in Fig. 9. In Fig. 12(1)–(3), the RFF and CFF of the original images are low and uniform, while the encrypted images display higher pixel intensity variations.

Floating frequency analysis evaluates the ability of encryption algorithms to generate uniformly random data in images. As shown in Fig. 12(1)–(3) and Table 7, the RFF (Random Floating Frequency) and CFF (Cumulative Floating Frequency) values of the encrypted images are significantly higher. Specifically, on the Red Channel, the RFF Mean is 161.95. On the Green Channel, the RFF Mean is 162.00 and the CFF Mean is 161.98. On the Blue Channel, the RFF Mean is 162.05 and the CFF Mean is 162.01. These high floating frequency values and uniformity indicate strong security, demonstrating that the encryption algorithm proposed in this paper provides excellent security.

Autocorrelation

The autocorrelation (AC) is calculated using formula 26, which assesses whether a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) based on the proposed hyperchaotic mapping produces a repeating sequence or pattern.

where AC \(\in\) [− 1, 1]. The autocorrelation of the PRNG shift \(k\) position is defined as \(k\), where \(A\) is the number of matches (same bits), \(D\) is the number of mismatches (opposite bits), and \(N\) is the length of the sequence. A value close to 1 indicates many bits are the same, a value close to − 1 indicates many bits are opposite, and a value close to 0 indicates an equal number of identical and opposite bits.

It can be clearly seen from the Fig. 13 that the AC of all tests, no matter how the shift changes, the value is very stable and basically close to zero.This indicates that 2D-HCFOS produces uniform pseudorandom numbers with no repeating patterns, no periodicity, and demonstrates strong randomness.

Time test

Our research demonstrates the effectiveness of a novel encryption and compression scheme specifically designed for image security in agricultural unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) applications. As shown in Table 8, the compression phase is highly efficient, taking less than 0.04 seconds, while the encryption phase ranges from 0.34668 to 0.35699 seconds. This combination of rapid compression and encryption underscores the method’s suitability for real-time operations, particularly in agricultural UAV scenarios where low latency is crucial. The encryption process is executed on a personal computer connected to the UAV, ensuring that sensitive agricultural data is secured efficiently. This approach significantly enhances the safety and efficiency of image handling, which is vital for agricultural UAV surveillance and reconnaissance missions that demand rapid data processing. As illustrated in Table 9, a comparative analysis with other published methods clearly demonstrates the superior encryption efficiency of our proposed scheme. This solution offers a practical approach for real-time encryption and compression in agricultural UAV image handling, effectively balancing security and time efficiency.

Conclusion

In this study, we propose a novel two-dimensional hybrid chaotic Fourier series and nonlinear coupled oscillator model (2D-HCFOS) that integrates compressed sensing techniques to address the challenge of slow encryption for agricultural images captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Our model exhibits superior chaotic performance, as evidenced by significantly higher Lyapunov indices and sample entropy, indicating enhanced cryptographic robustness and reliability. Compared to existing chaotic-based methods, our model offers heightened security for the image processing tasks of agricultural drones. The integration of compressed sensing technology with the Bonouille function generates a sparser measurement matrix, which is crucial for efficient real-time encryption and effectively mitigates the problem of slow image encryption. These advancements provide tangible benefits, including faster encryption speeds and increased security, making our proposed scheme superior to existing approaches in the field of agricultural drone image protection. The encryption process is conducted on a personal computer connected to the drone, ensuring that sensitive agricultural data is securely managed in real time. Future research could explore further optimizations of the model and its potential applications in other domains that require secure and efficient image management.

Data availability

The datasets used and analvsed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tsouros, D. C., Bibi, S. & Sarigiannidis, P. G. A Review on UAV-Based Applications for Precision Agriculture. Information10(11), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10110349 (2019).

Demestichas, K., Peppes, N. & Alexakis, T. Survey on security threats in agricultural IoT and smart farming. Sensors20(22), 6458 (2020).

Kokaji, A. & Goto, A. An analysis of economic losses from cyberattacks: Based on input-output model and production function. J. Econ. Struct.11(1), 34 (2022).

Cremer, F., Sheehan, B., Fortmann, M., Kia, A. N., Mullins, M., Murphy, F., & Materne, S. Cyber risk and cybersecurity: A systematic review of data, (2022).

Cheng, L., Liu, F. & Yao, D. Enterprise data breach: Causes, challenges, prevention, and future directions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov.7(5), e1211 (2017).

Song, H., Fink, G. A. & Jeschke, S. Security andPrivacy in CyberPhysical Systems: Foundations, Principles, and Applications 1–472 (Wiley, Chichester, 2017).

Erkan, U., Toktas, A. & Lai, Q. 2D hyperchaotic system based on Schaffer function for image encryption. Expert Syst. Appl.213, 119076 (2023).

Jiang, Q., Yu, S. & Wang, Q. Cryptanalysis of an image encryption algorithm based on two-dimensional hyperchaotic map. Entropy25(3), 395 (2023).

Gao, Y., Liu, J. & Chen, S. Image encryption algorithms based on two-dimensional discrete hyperchaotic systems and parallel compressive sensing. Multimed. Tools Appl.83(19), 57139–61 (2023).

Lai, Q., Liu, Y. & Yang, L. Image encryption using memristive hyperchaos. Appl. Intell.53(19), 22863–22881 (2023).

Ustun, D., Erkan, U., Toktas, A., Lai, Q. & Yang, L. 2D Hyperchaotic Styblinski-Tang map for image encryption and its hardware implementation’’. Multimed. Tools Appl.83(12), 34759–72 (2024).

Ott, E. Chaos in Dynamical Systems (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Benettin, G., Galgani, L., Giorgilli, A. & Strelcyn, J. M. Lyapunov characteristic exponents for smooth dynamical systems and for Hamiltonian systems a method for computing all of them. Part 1: Theory. Meccanica15(1), 9–20 (1980).

Hua, Z., Zhu, Z., Chen, Y. & Li, Y. Color image encryption using orthogonal Latin squares and a new 2D chaotic system. Nonlinear Dyn.104, 4505–4522 (2021).

Gao, X. Image encryption algorithm based on 2D hyperchaotic map. Opt. Laser Technol.142, 107252 (2021).

Teng, L., Wang, X., Yang, F. & Xian, Y. Color image encryption based on cross 2D hyperchaotic map using combined cycle shift scrambling and selecting diffusion. Nonlinear Dyn.105, 1859–1876 (2021).

Sun, J. 2D-SCMCI hyperchaotic map for image encryption algorithm. IEEE Access9, 59313–59327 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. A stable meaningful image encryption scheme using the newly-designed 2D discrete fractional-order chaotic map and Bayesian compressive sensing. Signal Process.195, 108489 (2022).

Nan, S. X., Feng, X. F., Wu, Y. F. & Zhang, H. Remote sensing image compression and encryption based on block compressive sensing and 2D-LCCCM. Nonlinear Dyn.108(3), 2705–2729 (2022).

Hua, Z., Zhou, Y. & Huang, H. Cosine-transform-based chaotic system for image encryption. Inf. Sci.480, 403–419 (2019).

Barani, Milad Jafari, Ayubi, Peyman, Valandar, Milad Yousefi & Irani, Behzad Yosefnezhad. A new Pseudo random number generator based on generalized Newton complex map with dynamic key. J. Inf. Secur. Appl.53, 102509 (2020).

Murillo-Escobar, Miguel Angel, Meranza-Castillón, Manuel Omar, López-Gutiérrez, Rosa Martha & Cruz-Hernández, César. Suggested integral analysis for chaos-based image cryptosystems. Entropy21(8), 815 (2019).

Murillo-Escobar, D. et al. Pseudorandom number generator based on novel 2D Hénon-Sine hyperchaotic map with microcontroller implementation. Nonlinear Dyn.111, 6773–6789 (2023).

Krakovská, A. Correlation dimension detects causal links in coupled dynamical systems. Entropy21(9), 818 (2019).

Hosseinzadeh, R., Zarebnia, M. & Parvaz, R. Hybrid image encryption algorithm based on 3D chaotic system and choquet fuzz integral. Opt. Laser Technol.120, 105698 (2019).

Rosenberg, E. Correlation Dimension. In Fractal Dimensions of Networks 177–194 (Springer, 2020).

Grassberger, P. & Procaccia, I. Measuring the strangeness of strange attractors. Physica9D, 189–200 (1983).

VICTOR CHURCHILL AND DONGBIN XIU,DEEP LEARNING OF CHAOTIC SYSTEMS FROM PARTIALLY-OBSERVED DATA

Innat, Global Wheat Challenge, Kaggle, created in 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ipythonx/global-wheat-challenge/data. Accessed on: Feb. 10, 2024.

Sarosh, P., Parah, S. A., Malik, B. A., Hijji, M. & Muhammad, K. Real-time medical data security solution for smart healthcare. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf.19(7), 8137–8147 (2023).

Bhaskar, M., Behera, P. & Sugata, G. A secure image encryption scheme based on a novel 2D sine-cosine cross-chaotic (SC3) map. J. Real-Time Image Process.18, 1–18 (2021).

Du, J. et al. A novel image encryption algorithm based on hyperchaotic system with cross-feedback structure and diffusive DNA coding operations. Nonlinear Dyn.112, 12579–12596 (2024).

Horé, A., & Ziou, D. Image Quality Metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM, 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, (2010), pp. 2366-2369, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR.2010.579.

Mondal, B. & Singh, S. A secure image encryption scheme based on cellular automata and chaotic skew tent map. J. Inf. Secur. Appl.45, 117–130 (2019).

Gupta, M. D. & Chauhan, R. K. Secure image encryption scheme using 4D-hyperchaotic systems based reconfigurable pseudo-random number generator and S-box. Integration81, 137–159 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank each reviewer for their contribution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software Development, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Editing, Validation, Literature Review, Deriving Results, Proofs, Writing. H.X.: Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Editing, Validation. Q.L.: Conceptualization, Literature Review, Writing, Discussion. X.Y.: Deriving Results, Proofs. X.Z.: Validation, Discussion. M.Z.: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Xia, H., Lin, Q. et al. Two-dimensional hyperchaos-based encryption and compression algorithm for agricultural UAV-captured planar images. Sci Rep 14, 22423 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73050-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73050-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Visually meaningful encryption for UAV image management achieving a balance between privacy and visual usability

Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications (2026)

-

Development of a Lightweight Secure Communication System for UAVs Enhanced by an Unconventional Chaotic Communication Architecture

Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems (2025)