Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is a prominent cause of female mortality on a global scale. Recently, there has been growing interest in utilizing blood and tissue-based biomarkers to detect and diagnose BC, as this method offers a non-invasive approach. To improve the classification and prediction of BC using large biomarker datasets, several machine-learning techniques have been proposed. In this paper, we present a multi-stage approach that consists of computing new features and then sorting them into an input image for the ResNet50 neural network. The method involves transforming the original values into normalized values based on their membership in the Gaussian distribution of healthy and BC samples of each feature. To test the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we employed the Coimbra and Wisconsin datasets. The results demonstrate efficient performance improvement, with an accuracy of 100% and 100% using the Coimbra and Wisconsin datasets, respectively. Furthermore, the comparison with existing literature validates the reliability and effectiveness of our methodology, where the normalized value can reduce the misclassified samples of ML techniques because of its generality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

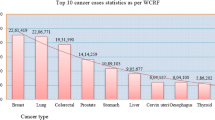

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cause of death among women worldwide after lung cancer, with fatalities of 685,000 in 20201. Currently, mammography is the gold standard and a tool that has the ability to detect breast cancer in its early stages. Despite the efficiency of mammography in detecting and diagnosing cancer, this method for low- or intermediate-risk women under 50 is subject to intense debate. Proponents argue for lower age screening, highlighting potential benefits like increased survival rates, improved workforce participation, and reduced treatment costs2. Conversely, opponents raise concerns about the side effects that may occur in the patient’s body due to frequent exposure to the radiation3. The concept of biomarkers, cancerous markers, bio-compounds, and physical indicators in the human body has prompted researchers and clinicians to focus on identifying all types of cancers and malignant tumors, including breast cancer, as well as how to categorize pathological conditions in general and cancerous conditions in particular4. Several studies have identified some molecular compounds with concentrations that differ between pathological and cancerous cases. These dysregulated concentrations have been categorized as helpful biomarkers for distinguishing between cancerous and healthy (H) cases. Haptoglobin, osteopontin (OPN), carcinoma antigen (CA) 15-3, CA125, and CA19-95 can all be detected using biomarkers like blood-based analysis, which are non-invasive and quantifiable features. Machine learning (ML) tools are therefore urgently needed to reach the necessary level of cancer diagnosis and prediction using available non-invasive biomarkers, as a result of the large data, which is typically close to healthy and cancer levels6,7.

The Coimbra breast cancer dataset (CBCD)8 is one of the most important datasets used to investigate the biomarker-based diagnosis and detection of BC using machine learning. The Coimbra dataset contains several biomarkers gathered from routine blood analysis such as insulin, leptin and glucose. Support Vector Machine (SVM) models employing resistin, BMI, glucose, and age exhibit the best performance with an average specificity of 87.1%, sensitivity of 84.85%, and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.888. Silva et al.9 used a fuzzy neural network method for breast cancer detection with CBCD and reached the best accuracy of 81.04% and a sensitivity of 81.93% using resistin, BMI, glucose, and age features. The fuzzy decision tree (FDT) was used to classify CBCD with the best accuracy of 70.69% and a sensitivity of 69.05%10. Aslan et al.11 transformed CBCD numerical data into image data, then augmented using various image augmentation approaches including rotation, reflection, translation and scale. Then the classification was carried out using significant convolutional neural network (CNN) models including ResNet50, AlexNet, and DenseNet201. ResNet50 model performed a classification accuracy of 95.33% . An SVM was integrated with a sequential backward selection model12 to enhance the feature ranking, and this approach showed an accuracy of 92% and sensitivity of 94% using resistin, glucose, homo, age, and BMI features. An expert system based on fuzzy logic and fuzzy rules given by oncologists13 was able to give an accuracy and sensitivity of 90% and 87%, respectively.

Another important diagnostic database for breast cancer is the Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (WDBC) dataset. WDBC contains 10 extracted features from breast tumors and was taken from 569 patients using 30 attributes14. Many ML-based approaches were proposed to detect and classify breast cancer based on those features. An optimized Radial Base Function (RBF) with SVM model15 was used in diagnosing breast cancer disease and has an accuracy of 96.91% and 97.84% sensitivity. Supervised (SL) and semi-supervised learning (SSL) logistic regression (LR) and K-nearest neighbor (KNN) were used to enhance the classification of malignant and benign breast cancer cases16. The LR gave an accuracy of (SL = 97% and SSL = 98%) and sensitivity of (SL: 93% and SSL: 100%), and the KNN model showed an accuracy of (SL: 98% and SSL: 97%) and sensitivity of (SL: 98% and SSL: 95%). Polynomial SVM was used with data exploratory techniques (DET) that involve feature distribution, correlation, elimination, and hyperparameter optimization17. This type of classifier performed an accuracy of 99.03% and a 99.3% F1-score. By applying a high-dimensionality reduction of features using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) as a pre-stage with SVM18, the accuracy and sensitivity became 98.82% and 98.41%, respectively. Optimizing and reducing features have been used to enhance deep learning approaches like genetic algorithms19 and wrapper methods20,21. The classification of WDBC features was improved using a ensemble of neural networks such as radial basis function networks (RBFN), feed-forward neural networks (FFNN), and generalized regression neural networks (GRNN)22. This hybrid ensemble gave an accuracy and a sensitivity of 95.34% and 93.05%, respectively, where the best performance was achieved by FFNN with 94.41% and 89.33%. A shallow artificial neural network (ANN) model with a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function in one hidden layer only23 was used to enhance the classification of the WDBC dataset, and the final accuracy and sensitivity were 99.47% and 99.59%, respectively. In order to improve the accuracy of breast cancer detection, Rasool et al.17 developed four alternative prediction models and provided data exploratory methods (DET). In order to establish reliable feature categorization into malignant and benign classes, four-layered essential DET, such as feature distribution, correlation, removal, and hyperparameter optimization, were thoroughly investigated prior to models . The WDBC and BCCD datasets were used to test these proposed methods and classifiers. Using the WDBC dataset, the models’ diagnostic accuracy improved with the DET, where polynomial SVM, LR, KNN, and EC gave an accuracy of 99.03%, 98.06%, 97.35%, and 95.61%, respectively17. Integrating deep features from CNN with logistic regression (LR) and stochastic gradient descent (SGD) classifiers in one model, with a voting mechanism for final prediction achieved an accuracy of 100%, demonstrating a significant enhancement over the original features32.

Accordingly, a lot of efforts were exerted to enhance the biomarkers and features-based detection of breast cancer because of many factors including its simplicity and absence of radiation exposure. Many ML-based approaches were proposed and enhanced, either with pre-stages or hybrid classifiers based on many machine learning tools. CNN models represent a new era of high-performance and accurate image classification techniques26,27,28,29,30 that include extracting deep features using convolution and pooling, then classifying them using fully connected neural networks. Aslan et al.11 employed CNN in biomarker classification by converting those values into augmented images to be appropriate input for the CNN model. Four data augmentation tools (rotation, scale, reflection, and translation) were applied to increase the number of input images, which means that accuracy increased based on artificially created samples rather than working on the entity of features. Additionally, the common limitation of the related work is the generality of the model since the value of features may change by obtaining new samples.

In our paper, we propose a new type of feature engineering approach by converting the raw value of features into normalized features based on their Gaussian distribution in healthy and BC populations of samples. The pre-processing consists of converting the raw values of the samples into normalized values based on their membership in the Gaussian distributions of healthy and BC samples on feature basis. Then, the normalized features are used to construct an image to implement image classification using CNN model11. The CBCD and WDBC datasets were used to examine the detection approach, and the results were addressed using each one individually.

Methods and materials

Datasets

Coimbra breast cancer dataset

The Coimbra dataset is a publicly available dataset31 and consists of biomarkers extracted from routine blood analysis8. CBCD was created between 2009 and 2013 by the Gynecology Department of the Coimbra Hospital and University Center (CHUC) in Portugal by recruiting female patients diagnosed with breast cancer. The CBCD dataset includes 116 samples, including 64 BC and 52 healthy samples. CBCD consists of nine features categorized into healthy and breast cancer. The nine features of this dataset involve age #1 (year), insulin #4 (\(\mu\)U/mL), glucose #3 (mg/dL), leptin #6 (ng/mL), adiponectin #7 (\(\mu\)g/mL), resistance #8 (ng/mL), body mass index (BMI) #2, homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) #5, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) #9 (pg/dL). Each feature has a specific numerical label, e.g., age #1, for easier reference in the next sections.

Wisconsin breast cancer dataset

The Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (WDBC) dataset is a publicly available dataset and contains 10 features that were computed based on 30 characteristics of biopsies and fluidic samples from 569 patient14. The characteristics were extracted using Xcyt software based on cytological feature analysis from the digital scan. The main features are 10, and each feature is expressed by mean, worst, and standard error values, which result in 30 attributes. The final version of WDBC contains 10 features in addition to the case label, as follows: malignant (M=BC) and benign (B=H). The features include texture #2 (standard deviation of gray-scale values), area #4, compactness #6 (perimeter2/area - 1.0), perimeter #3, concavity #7 (severity of concave portions of the contour), smoothness #5 (local variation in radius lengths), concave points #8 (number of concave portions of the contour), symmetry #9, fractal dimension #10 (“coastline approximation” - 1), and radius #1. In our study, we use only the mean value of the sample or feature to examine the efficiency of the proposed approach13.

Normalizing features using Gaussian distribution

The Gaussian distribution (GD) is the most common distribution function for independent and randomly generated variables24. The GD function can be expressed using two parameters: the mean, or average, and the standard deviation24. In this study, we used the GD formula to scale the features of the breast cancer dataset into new values that express the membership of the sample or feature in the GD space. Empirically, we found that by expressing the values of the feature into two (H and BC) GD memberships, we will have new sub-features with more resolution, as shown in Fig. 1. To estimate GD from healthy and BC samples, we calculated the mean (\(\mu\)) and the standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) of healthy and BC cases individually regarding each feature. Accordingly, each feature can be normalized into two values of GD membership from healthy and breast cancer cases using Eq. 1, where (n) refers to the feature and (case) refers to the class. From now on in the paper, the GD membership function (GDMF), as a term, refers to GD distribution; e.g., H-GDMF refers to the GD membership function of healthy samples in a specific feature.

Feature-based image

The computed new features based on the GDMF of healthy and BC samples are used to construct a normalized image, as shown in Fig. 2A. Considering the case of classifying the CBCD features, the nine features are expanded into an image after calculating the GDMF of each sample (see previous section). The position and distribution of features in the image depend on the GD of healthy and BC samples of each feature (see Results, Fig. 4). For each record in the dataset, the constructed image consists of two sub-images (Fig. 2B), where the red part belongs to H-GDMFs of features and the blue one to BC-GDMFs. For example, Fig. 2B shows the image of CBCD data where features #4 and #5 occupy the biggest sequars due to their high discrimination between H and BC samples in GDMFs (see Results, Fig. 4), and vice versa for #1, #2, #3, and #9 features. The red and blue sub-images in Fig. 2B are stacked together in such a way that the significant features from H- and BC-GDMFs are close to each other while the rest are placed away from the center. Accordingly, each record is represented as an image with double normalized features based on H- and BC-GDMFs in a specific order related to GD between healthy and BC samples of each feature. Additionally, the CBCD and WDBC datasets have a different image structure based on feature importance. Two example images of healthy and BC samples from CBCD are shown in Fig. 2C.

CNN models

ResNet50 is a 50 layers CNN model25 with residual blocks that contain multiple convolutional layers along with connections, allowing for easier training of deeper networks. In the provided model schematic (Fig. 3), an initial convolutional layer with a 7x7 kernel and 64 filters processes the input image, followed by a 3x3 max pooling layer. The network then consists of several stacked residual blocks. Each block contains layers of 1x1, 3x3, and again 1x1 convolutions, with the number of filters increasing with depth. These blocks are grouped and color-coded to denote distinct segments within the architecture. In ResNet50, skip connections are significant components, which are crucial for addressing the challenges associated with training very deep neural networks. Skip connections, or residual connections, allow the network to focus on learning residual mappings rather than the complete desired mapping. This is achieved by introducing shortcut connections that bypass one or more layers, directly adding the input of a block to its output. The core component of this architecture is the residual block, which incorporates multiple convolutional layers. Each block is designed around the principle that the network should have the ability to perform identity mapping when beneficial. The mathematical representation of a residual block’s output is F(x)+x, where F(x) denotes the transformational output of the convolutional layers and x is the input. When the dimensions of x and F(x) are identical, the computation adheres to the standard equations but in some cases, there are instances where the dimensions of x and F(x) differ. Under such circumstances, a scaling matrix W is introduced to align the dimensions necessary for the shortcut or skip connection. This adjustment ensures that x and F(x) are appropriately sized to serve as the input for the subsequent layer, as described by equation 2, where \(W_s\) provides additional parameters to the model, allowing it to avoid the issues associated with dual dimensionality:

The architecture ends with an adapted sequence of layers tailored for binary classification: after the base model, a flattening layer transforms the 2D features into a 1D vector, followed by a dense layer with 1000 neurons using ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation to introduce non-linearity and enhance learning capabilities. The final layer is a dense layer with two neurons and a softmax activation function. Although a single neuron with sigmoid activation is commonly used for binary tasks, using two neurons with softmax provides explicit probabilities for each class, facilitating a more interpretable model output and ensuring compatibility with our loss function, which expects probabilities per class. The ResNet-50 model is trained using stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM) as the optimizer, known for its effectiveness in fast convergence. We set the training for 6 epochs, each representing a full pass through the dataset, and a mini-batch size of 10. This size strikes a balance between computational efficiency and the stability of error gradient estimation. The learning rate is carefully set at 0.0003 to allow for gradual and precise adjustments in the weights, ensuring that the model does not converge too hastily to a suboptimal solution. The training data is shuffled before each epoch to prevent the model from learning any order in the training data, which might affect its ability to generalize.

Performance metrics

The performance is measured using formula of accuracy, sensitivity and F1-score Eqs. 3,4,5:

True positive (TP) refers to instances where the prediction correctly identifies a sample as BC. True negative (TN) indicates instances where the prediction accurately identifies a sample as H. False positive (FP) denotes cases where the prediction wrongly identifies a sample as BC when it is H. Conversely, false negative (FN) signifies instances where the prediction erroneously identifies a sample as H when it is BC.

Results

The results section addresses the outcomes of applying the proposed method to classify CBCD and WDBC datasets separately in details.

Coimbra Dataset (CBCD)

The computed H and BC Gaussian distributions of CBCD features are shown in Fig. 4. The GD of insulin, HOMA, and glucose exhibit different distributions between H and BC samples. On the other hand, BMI, adiponectin, resistin, and MCP-1 have a semi-similar GDs among H and BC samples but are still able to increase the likelihood of discrimination between them using CNN. In contrast, leptin has no difference in GD between healthy and BC cases, which makes it non-useful concerning our approach.

The proposed method (Fig. 3) for classification was implemented, where the samples of CBCD were converted into images (see methods section). Different ratios of training and testing data were used to examine the efficiency of the proposed approach with a low number of data points for building a powerful biomarker-based detection system. The ratio of training to all data for CNN were 50%, 65%, 75%, and 80%.

In our work, it was important to address the performance with and without data augmentation techniques to increase the dataset11. The testing performance of ResNet50 with and without data augmentation is shown in Fig. 5. With data augmentation (Fig. 5A), the model exhibits a slightly enhanced accuracy, ranging from 96.12% to a perfect 100%, across different testing data ratios. Conversely, without data augmentation (Fig. 5B), the accuracy also reaches 100% using 20% and 25% of data for testing but starts from 95% at lower testing data ratios. Sensitivity, reflecting the model’s ability to correctly identify positive instances, demonstrates consistent performance with and without data augmentation, maintaining high scores ranging from 95.45% to 100% across all scenarios. Similarly, the F1-score which reflects the model’s balance between precision and recall, gave a narrow range from 97.02% to 100%, compared to scores ranging from 95.45% to 100% without augmentation.

A comparison of related work that used Coimbra data to develop diagnostic systems is outlined in Table 1. Among the methods examined, CNN gives the highest accuracy and sensitivity. The method in11 demonstrates the effectiveness of Resnet50 with an accuracy of 95.33% and sensitivity of 96% but with implementing data augmentation. Similarly, the proposed approach, employing CNN with feature-based image without data augmentation, achieved an accuracy of 96.55% and sensitivity of 96.88% at a 50%-50% training-testing split, and reached 100% accuracy and sensitivity at an 80%-20% split. On the other hand, methods such as fuzzy neural networks and fuzzy decision trees, as demonstrated by9 and10 respectively, exhibit comparatively lower accuracy and sensitivity scores, suggesting potential limitations in handling intricate classification tasks. Additionally, SVM with a sequential backward selection model12 achieved good performance with accuracy of 92%.

Wisconsin Dataset (WDBC)

The computed GDMFs from WDBC samples regarding benign and malignant cases are shown in Fig. 6. The most distinguishing GDMFs are “Raduis”, “Perimeter”, “Area”, “Compactness”, “Concavity”, and “Concave,” where samples among two cases are clearly different and have diverse ranges of membership. The GD of “Fractal” shows the lowest difference between “B” and “M” cases, and that results in a similar membership between samples for both cases. Those noticeable and different GDMFs of malignant and benign cases stand behind the high performance of classification in the literature18,19,20,21,22,23, but there is no direct use of those different functions as features with ML methods except for reducing the features with low-distinguished GD graphs16,17,18.

Where the training performance and procedure are similar to what been mentioned in the previous CBCD section, the testing performance using WDBC is shown in Fig. 7. Specifically, at a testing data ratio of 50%, the model achieved an accuracy of 96.14%. Moreover, the sensitivity remained consistently high, ranging from 96.46% to 100% across varying testing data ratios. Similarly, the F1-score maintained robust performance, ranging from 95.19% to 100%, underscoring the model’s balanced performance in both identifying positive cases and minimizing false positives. Notably, at testing data ratios of 25% and 20%, the model achieved acceptable accuracy, sensitivity, and F1-score, suggesting its robustness even with limited testing data.

The comparison with previous efforts regarding the classification of the WDBC dataset is addressed in Table 2 Using SVM models with pre-processing approaches like feature distribution and correlation17 or high-dimensionality reduction of features18 made a good contribution to the performance of classification. Semi-supervised ML tools16 had better performance with a sensitivity of 100%. On the other hand, the shallow neural network with hybrid neural \(\hbox {cells}^{?}\) reached an accuracy and sensitivity of 98.82% and 98.41%, respectively. The proposed approach of using GDMF to generate a new image of normalized features increased both accuracy and sensitivity to 100% using 20% of the data as testing samples. By partitioning the dataset to 50% of training and testing data, the accuracy became 96.14% with a sensitivity of 96.46%. Integrating deep features from CNN with LR and SGD classifiers achieved an accuracy of 100%32. The difference between the previous approaches15,18,23 and the proposed approach is that the estimation of normalized features for each attribute or case gives a wider space of information and gives ML tools much more distinctive sub-features from the original features, which eases the process of training and testing regarding the used ML tool.

Discussion

Biomarker-based cancer detection is considered one of the most promising tools in non-invasive cancer detection and prediction techniques. Many machine learning tools were investigated and enhanced to give this field more powerful outcomes with high performance and reliability in classification8,9,10,11. In this paper, a new approach to feature engineering is proposed for normalizing features based on the H/BC-GDMF. The normalized features were sorted based on their importance into one image, and the latter was used as an input for the ResNet50 CNN classifier. The final performance of the proposed approach with 100% accuracy and sensitivity using both CBCD and WDBC data highlights the proper use of GD in reinforcing the efficiency of CNN-based cancer detection systems11,26,27,28,29,30,32. The GDMFs of CBCD features (Fig. 4) clearly interpret the main cause of getting low-performance values in9,10,12, where the dominant reason is the big similarity of values among all samples regarding the cases. Some literature has attempted to reduce the number of processed features8,9 in order to avoid other features with low resolution between H and BC cases. On the other hand, since the image-based classification was first suggested by Aslan et al.11, the data augmentation raised a lot of concerns about the reliability of the model. Data augmentation can be implemented on medical images, cars, animals, etc. because it emulates the different situations of those images. Concerning the conversion of biomarker features into images, data augmentation leads to irrelevant data in terms of biomarker order and false input for CNN. Despite slight enhancements in accuracy and F1-score with data augmentation in our results, the disparities are not substantial, especially considering the high performance achieved with and without data augmentation, particularly at higher testing data ratios (25% and 20%), which emphasize the impact of the proposed approach in enhancing this type of image-based classification without the data augmentation. Using WDBC data, Umar et al.32 used a 1-dimensional CNN model as a deep feature extraction tool, followed by LR and SGD classifiers in one model, with a voting mechanism for final prediction that achieved an accuracy of 100%. While different approaches demonstrate the efficacy of CNNs in breast cancer prediction, especially using numerical data, they diverge in their feature engineering strategies and model architectures. The GDMF approach focuses on feature normalization and image-based classification, while32 prioritizes the fusion of extracted and deep convoluted features within an ensemble framework. Although this approach has shown promising results, it also needs to be tested across diverse datasets. This will give rise to the reliability, effectiveness, and acceptance of the model in real-world clinical settings, which will eventually lead to better patient outcomes as well as better healthcare decisions.

Conclusion

In this paper, a new method of feature engineering is proposed to enhance and increase the features based on the Gaussian distributions of healthy and BC samples on a feature basis. The approach relies on computing the Gaussian distribution function of healthy and BC samples for each feature. The Gaussian distribution membership expresses how much is close to or far from healthy or benign, as well as cancer or malignant cases at the same time. By implementing the approach on CBCD and WDBC separately with Resnet50 net and comparing the accuracy and sensitivity with the related literature, we found a discriminative enhancement in the performance metrics, which reach 100% using WDBC and 100% using CBCD datasets. The concept of replacing features with normalized features in their Gaussian distribution suggests many ways to improve the deep learning approach for classification purposes. The future work will focus on testing the approach on different types of cancer and diagnostic datasets.

Data availability

All used data are benchmark and are freely available in repositories. The Coimbra dataset analyzed during the current study is available in the UCI Machine Learning Repository, https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Breast+Cancer+Coimbra. The Wisconsin dataset is available on https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/17/breast+cancer+wisconsin+diagnostic. Any further data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Malik, J. A. et al. Drugs repurposed: An advanced step towards the treatment of breast cancer and associated challenges. Biomed. & Pharmacother.145, 112375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112375 (2022).

Zubor, P. et al. Why the gold standard approach by mammography demands extension by multiomics? application of liquid biopsy mirna profiles to breast cancer disease management. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20122878 (2019).

Ocasio-Villa, F. et al. Evaluation of the pink luminous breast led-based technology device as a screening tool for the early detection of breast abnormalities. Front. Medicine8, 805182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.805182 (2022).

Hong, R. et al. A review of biosensors for detecting tumor markers in breast cancer. Life12, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12030342 (2022).

Opstal-van Winden, A. W. et al. A bead-based multiplexed immunoassay to evaluate breast cancer biomarkers for early detection in pre-diagnostic serum. Int. J. Mol. Sci.13, 13587-13604, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131013587 (2012).

Farina, E., Nabhen, J. J., Dacoregio, M. I., Batalini, F. & Moraes, F. Y. An overview of artificial intelligence in oncology. Futur. Sci. OA 8, FSO787, https://doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2021-0074 (2022).

Zheng, D., He, X. & Jing, J. Overview of artificial intelligence in breast cancer medical imaging. J. Clin. Medicine12, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020419 (2023).

Patrício, M. et al. Using resistin, glucose, age and bmi to predict the presence of breast cancer. BMC cancer18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3877-1 (2018).

Silva Araújo, V. J., Guimarães, A. J., de Campos Souza, P. V., Rezende, T. S. & Araújo, V. S. Using resistin, glucose, age and bmi and pruning fuzzy neural network for the construction of expert systems in the prediction of breast cancer. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 1, 466-482, https://doi.org/10.3390/make1010028 (2019).

Idris, N. F. & Ismail, M. A. Breast cancer disease classification using fuzzy-id3 algorithm with fuzzydbd method: automatic fuzzy database definition. PeerJ Comput. Sci.7, e427. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.427 (2021).

Aslan, M. F., Sabanci, K. & Ropelewska, E. A cnn-based solution for breast cancer detection with blood analysis data: Numeric to image, https://doi.org/10.1109/SIU53274.2021.9477801 (2021). Paper presented at the 29th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Istanbul, Turkey, 09-11 June 2021.

Alnowami, M. R., Abolaban, F. A. & Taha, E. A wrapper-based feature selection approach to investigate potential biomarkers for early detection of breast cancer. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci.15, 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrras.2022.01.003 (2022).

Thani, I. & Kasbe, T. Expert system based on fuzzy rules for diagnosing breast cancer. Heal. Technol.12, 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-022-00643-0 (2022).

Wolberg, W. H., Street, W. N. & Mangasarian, O. L. Breast cancer wisconsin (diagnostic) data set (1992). Figshare https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/breast+cancer+wisconsin+(diagnostic)

Maglogiannis, I., Zafiropoulos, E. & Anagnostopoulos, I. An intelligent system for automated breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis using svm based classifiers. Appl. intelligence30, 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-007-0073-z (2009).

Al-Azzam, N. & Shatnawi, I. Comparing supervised and semi-supervised machine learning models on diagnosing breast cancer. Annals Medicine Surg.62, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.12.043 (2021).

Rasool, A. et al. Improved machine learning-based predictive models for breast cancer diagnosis. Int. journal environmental research public health19, 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063211 (2022).

Omondiagbe, D. A., Veeramani, S. & Sidhu, A. S. Machine learning classification techniques for breast cancer diagnosis. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng.495, 012033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/495/1/012033 (2019).

Aalaei, S., Shahraki, H., Rowhanimanesh, A. & Eslami, S. Feature selection using genetic algorithm for breast cancer diagnosis: experiment on three different datasets. Iran. journal basic medical sciences19, 476 (2016).

Saoud, H., Ghadi, A., Ghailani, M. & Abdelhakim, B. A. Using feature selection techniques to improve the accuracy of breast cancer classification, In The Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Smart City Applications 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11196-0_28 (2018).

Naik, A. K., Kuppili, V. & Edla, D. R. Efficient feature selection using one-pass generalized classifier neural network and binary bat algorithm with a novel fitness function. Soft Comput.24, 4575–4587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-019-04218-6 (2020).

Yavuz, E., Eyupoglu, C., Sanver, U. & Yazici, R. An ensemble of neural networks for breast cancer diagnosis (2017). Paper presented at the International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Antalya, Turkey, 05-08 October 2017.

Alshayeji, M. H., Ellethy, H. & Gupta, R. Computer-aided detection of breast cancer on the wisconsin dataset: An artificial neural networks approach. Biomed. Signal Process. Control.71, 103141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103141 (2022).

Folks, J. L. & Chhikara, R. S. The inverse gaussian distribution and its statistical application-a review. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Ser. B: Stat. Methodol. 40, 263-275 (1978).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 . IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 Jun. (2016)

Salehi, A. W. et al. A Study of CNN and Transfer Learning in Medical Imaging: Advantages, Challenges. Future Scope. Sustainability.15, 5930. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075930 (2023).

Ursuleanu, T. F. et al. Deep learning application for analyzing of constituents and their correlations in the interpretations of medical images. Diagnostics.11, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081373 (2021).

Jiang, X., Hu, Z., Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. Deep learning for medical image-based cancer diagnosis. Cancers.15, 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15143608 (2023).

Arabahmadi, M., Farahbakhsh, R. & Rezazadeh, J. Deep learning for smart Healthcare-A survey on brain tumor detection from medical imaging. Sensors.22, 1960. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051960 (2022).

Huang, S. Y., Hsu, W. L., Hsu, R. J. & Liu, D. W. Fully convolutional network for the semantic segmentation of medical images: A survey. Diagnostics.12, 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112765 (2022).

Breast Cancer Dataset. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Breast+Cancer+Coimbra (accessed on 1 September 2023).

Umer, M. et al. FBreast Cancer Detection Using Convoluted Features and Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithm. Cancers.14, 6015. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14236015 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Draft paper: H.A.E. and E.I. Data analysis: H.A.E. Writing/editing: E.I. Supervision: M.F.A. and E.I. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Essa, H.A., Ismaiel, E. & Hinnawi, M.F.A. Feature-based detection of breast cancer using convolutional neural network and feature engineering. Sci Rep 14, 22215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73083-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73083-7