Abstract

Enhancing work safety behaviors among Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Suppliers (SMMs) is crucial for establishing a more secure and efficient supply chain. Since the foundation of safety lies in positive prevention, it is crucial that SMMs adopt proactive and pro-social work safety behaviors that transcend mere compliance with standard regulations. Present-day diversified supply chain safety management apply varying degrees of pressures on SMMs. The effectiveness of such pressures, as well as their potential to spawn advanced safety behaviors in SMMs, is a matter of investigation. This research investigates the impact of Supply Chain Safety Management Pressure(SCSMP) on the SMMs’ Work Safety Behaviors(WSB). A theoretical framework is constructed, grounded in institutional theory and theory of planned behavior, which earmarks three distinct dimensions of SCSMP: Coercive Pressure(CP), Mimetic Pressure(MP), and Normative Pressure(NP). The survey of 265 SMMs facilitated an assessment of the SMMs’ Willingness for Responses(WR), which includes their Willingness for Adaptive Responses(WAR) and Willingness for Co-creative Responses(WCR). Subsequently, the resulting WSB entail Safety Compliance Behavior(SCB), Proactive Safety Behavior(PSB), and Pro-social Safety Behavior(PsSB). Among these, SCB is categorized as a basic safety behavior, while PSB and PsSB which emphasize voluntary, active, and cooperative actions, are classified as advanced safety behaviors. Our research findings underscore the substantial influence of the SCSMP in shaping WSB. WR serves as a critical intermediary, connecting external pressures with internal organizational practices. In particular, WCR is instrumental in the formation of advanced safety behavior. The theoretical contribution of this research is manifested in its enhancement of our comprehension regarding the determinants of WSB among SMMs. Furthermore, it addresses the literature gap in elucidating the effectiveness of supply chain safety management and the mechanisms behind the formation of WSB. The practical significance lies in elevating the overall safety standards throughout the supply chain and minimizing safety-related hazards among SMMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the proliferation of small and medium-sized manufacturing suppliers(SMMs) in China has been impressive. These SMMs, serving as vital elements within the supply chains of core manufacturing enterprises, have substantially aided in fortifying the international competitive edge of these core enterprises1,2,3. However, due to non-standard safety conduct, they have faced numerous production risks and have become areas with a high frequency of production accidents. These incidents not only endangers social safety but also has caused damage to the sustainable development of core enterprises4,5. For instance, the explosion at the Zhongrong Metal Products facility caused in a long-term supply disruption and severely affected the supply chain production process of the core enterprise, General Motors. Supply chain enterprises integrate to form a mutualistic network of shared interests, necessitating that core enterprises not only be vigilant of their own work safety hazards but also of the stability of the entire supply chain’s work safety6,7,8. Consequently, a significant number of core enterprises have started to adopt supply chain work safety management practices7,9. For instance, Kunshan Q Technology Microelectronics places a high priority on the work safety levels of suppliers within its vendor selection process, avoiding partnerships with suppliers who do not meet specific work safety benchmarks. Huawei has implemented various strategies to enhance suppliers’ safety levels, including the digital transformation of supplier risk assessments, the deployment of intelligent AI systems for detecting work safety infractions, and support in achieving work safety certifications, among other initiatives. Similarly, Giant (China) has embarked on a collaboration termed the “Safety Production Industrial Chain Cluster Agreement” with its supply chain members. This initiative promotes a management model based on work safety, encouraging shared progress and cooperation among its supply chain members in this field. Current work safety management measures in the supply chain are varied and comprehensive. Specifically, they include establishing work safety standards and systems for suppliers; incorporating work safety responsibility clauses in procurement contracts; signing safety agreements; assessing the safety levels of companies within the supply chain; identifying and controlling accident risks in the supply chain; providing resources such as work safety training, guidance, consulting, or technology; organizing work safety learning, interaction, and communication among supply chain members, and even leading the entire chain in developing, innovating, promoting, and applying new work safety technologies or advanced safety management systems, among other initiatives. The growing diversity of supply chain safety management initiatives has led to a wide range of practice scenarios9,10,11. These core enterprises attempt to use various supply chain safety management measures to encourage SMMs to develop beneficial work safety behaviors. However, are these management measures truly effective?

This issue has garnered widespread attention from both entrepreneurs and the academic community. The Work Safety Behaviors(WSB) of SMMs are complex, encompassing not only fundamental Safety Compliance Behavior(SCB) but also Proactive Safety Behavior(PSB) and Pro-social Safety Behavior(PsSB). SCB emphasizes fulfilling and adhering to safety regulations. PSB underscores the proactive initiative taken in the process of improving safety levels. PsSB highlights the altruistic, cooperative, and voluntary aspects of safety actions12. Compared to SCB, the latter two behaviors go beyond the general enforcement of safety contracts, emphasizing voluntary, active, and cooperative actions by companies13. As the primary entity responsible for work safety, SMMs must recognize that merely fulfilling safety contracts is insufficient. Some accident investigations reveal that despite companies obtaining legal and compliant work safety certifications, accidents still occur. This indicates that, beyond SCB, there should be an increased focus on stimulating PSB and PsSB within SMMs. When considering the complex WSB of SMMs within the framework of supply chain management, it is evident that supply chain work safety management falls under the broader category of supply chain social responsibility management. Consequently, the WSB of SMMs can also be viewed as a form of social responsibility practice9. Current research primarily focuses on constructing supply chain social responsibility management models from the perspective of core companies and how these companies address unethical supplier behaviors through standardization, evaluation and supervision, assistance, and collaboration. There is a lack of validation regarding the effectiveness of these management, and even less exploration into the specific behavioral impacts on the managed parties—the SMMs.

Although there is currently no unified standard for supply chain work safety management, in general, supply chain work safety management refers to integrating work safety management elements into supply chain management and implementing a series of measures to enhance the overall safety level of supply chain members, thereby preventing potential accidents at various stages, nodes and members10,11. These supply chain safety management initiatives establish an institutional context for SMMs. According to institutional theory, organizations are embedded within institutional context that exert pressure on their survival14,15. Therefore, the context of supply chain work safety management also imposes various pressures on SMMs.

Some scholars believe that the institutional perspective is crucial for understanding how stakeholders influence companies to adopt social responsibility practices, especially in supply chain management16,17,18. Supply chain pressure—especially the coercive pressure arising from social responsibility clauses in codes of suppliers’ conduct and procurement standards (such as work safety responsibility clauses)10,11—is considered a major driving force for SMMs to engage in social responsibility practices19,20. Although most research focuses on the coercive pressure from the supply chain management and indicates a positive correlation between such coercive pressure and the practices of SMMs21,22, due to limitations in motivation and capability, SMMs often perceive such practices negatively. This is especially true in the area of work safety, where accident risks are delayed, uncertain, and easily concealed, making it challenging for SMMs to translate supply chain requirements into specific WSB.

Although supply chain pressure is often understood as coercive pressure, some scholars suggest that supply chain members can also exert pressure on SMMs in different ways17,20. For example, in the process of supply chain safety management, as supply chain members participate, engage in mutual learning, and exchange ideas, they can form similar work safety values and norms, which can bring benefits. These benefits, in turn, can exert pressure. Similarly, when supply chain members (especially collaborators, competitors within supply chain) gain advantages and success by complying with, implementing, learning, and participating in supply chain work safety management, SMMs may feel mimetic pressure5,16. Therefore, according to institutional theory14,15, normative and mimetic pressures from supply chain also appear to play an important role in the work safety practices of SMMs. In summary, we refer to this series of pressures arising from the supply chain safety management context as “Supply Chain Safety Management Pressure (SCSMP).” This concept is similar to the supply chain pressure, emphasizing the interpretation of the supply chain’s impact on organizations through the perspective of institutional theory. The distinction lies in its specific application within the context of supply chain safety management.

Some scholars have used the institutional theory to conduct an overall assessment of the relationship between supply chain pressure and the social responsibility behaviors of SMMs23,24,25. However, the impact of supply chain pressure within specific management contexts on the behaviors of SMMs remains largely unexplored, particularly in the area of work safety20,22. Recent studies have also assessed the necessity of investigating the impact of specific pressures on the multidimensional behaviors of SMMs26,27,28. Due to the varying supply chain work safety management models, measures, atmospheres, and positions within the supply chain that each SMMs faces, the pressure they experience from supply chain safety management are multifaceted and complex. When faced with diverse pressure, companies diverge in their choice to either comply or act autonomously. Some scholars, from a social perspective, believe that organizations will conform to external institutional expectations29,30. Other scholars argue that in a complex and multifaceted pressures, it is challenging for organizations to fully comply with all institutional requirements, and they must make choices based on their own strategic needs31,32. This raises the question: What WSB do SMMs exhibit under the SCSMP? When facing coercive pressure, SMMs should exhibit SCB to ensure their legitimacy33. However, in addition to this, SMMs are influenced by multifaceted SCSMP. Can these pressures foster the development of PSB and PsSB among these suppliers? Given the current lack of exploration into how specific dimensions of supply chain pressure affect the differential behaviors of enterprises, it is theoretically valuable to investigate how the specific WSB of SMMs are influenced by multifaceted pressure within the context of supply chain safety management.

Additionally, this study explores the indirect influence of SCSMP on WSB of SMMs, as institutions are objective and independent of enterprises34. This objective pressure from supply chain management is initially perceived by the company manager before SMMs take action35,36. However, in SMMs, characterized by their limited scale and workforce, the alignment between managerial decisions and organizational execution is frequently observed, indicating a convergence of manager perception with that of the organization. The behavior of the enterprise largely depends on the subjective perception of SCSMP and the willingness for responses37,38. Therefore, the willingness of SMMs to respond to pressures serves as a bridge between SCSMP and the WSB of SMMs, functioning as a mediating variable within this relationship34,39.

This study surveyed 265 SMMs to investigate the relationship between multifaceted SCSMP and the specific WSB of SMMs. It aims to address two questions:

-

(1)

Can the multifaceted pressures from supply chain safety management influence SMMs to carry out PSB and PsSB?

-

(2)

Under multifaceted SCSMP, what are the specific impact pathways for the various work safety behaviors of SMMs?

Answering these questions can help theoretically explain the impact of multifaceted SCSMP on the specific WSB of SMMs. This can fill the gap in the literature regarding the validation of the effectiveness of supply chain social responsibility management, and serve as a demonstration and expansion of institutional theory. Practically, this study offers valuable recommendations for validating the effectiveness of supply chain work safety management practices and exploring how core enterprises can genuinely enhance the work safety levels of SMMs, thereby improving the overall work safety levels of the supply chain.

The study is divided into seven sections. The “Introduction” section describes the research background, theoretical value, and significance of the study. The “Theoretical framework and hypotheses development” section constructs the theoretical framework and proposes related hypotheses. The “Method” section outlines the research design, data collection methods, provides a general description of the sample, and details the development and testing of the scales. The “Data analysis” section covers the tests for direct and mediating effects and presents the results. In the “Discussion” section, we explore the theoretical and practical implications of the findings. Finally, the “Conclusion” and “Limitations and future prospects” sections summarize the paper and discuss future research directions.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

Theoretical framework of supply chain safety management pressure (SCSMP) based on institutional theory

In recent years, scholars have increasingly focused on how to encourage SMMs to engage in social responsibility practices, such as work safety, environmental protection, green practices, and so on40,41,42. Specifically, since government regulation of such activities in SMMs is far more challenging than in large enterprises, supply chain management is viewed as an effective means to enhance the social responsibility practices of SMMs, with pressure from supply chain management being the underlying driving force10,18,23,43,44. This argument aligns with institutional theory, which emphasizes the pressure exerted by the external environment on organizations14,15.

Institutional theory posits that coercive pressure arises from formal contracts imposed by other organizations that hold resource advantages. Therefore, these pressures can manifest at the corporate level14,15. In the context of supply chain safety management, core enterprises use their resource advantages to establish work safety systems, sign work safety contracts, assess safety performance, and penalize non-compliant SMMs. These formal contracts, institutional norms, and safety regulations collectively create Coercive Pressure(CP)9. Current research often regards supply chain pressure as CP. Baden(2011), Ayuso(2013), and Huq(2016) argue that the influence of the supply chain management on suppliers within it arises directly from the constraining effect of CP generated by supply chain contracts, norms, and assessments10,43,45.

However, some scholars suggest that, beyond CP, supply chain members can exert influence and apply pressure on SMMs through various methods17,20. Institutional theory posits that institutional pressure also includes mimetic pressure and normative pressure. mimetic pressure refers to the pressure on organizations to gain legitimacy and additional benefits by imitating successful entities14,15. Previous scholars believed that mimetic pressure primarily comes from a wide range of competitors46,47. However, in practice, supply chain members (especially collaborators and competitors within the supply chain) may also exert mimetic pressure on SMMs48. For example, McFarland (2008) found that when collaborators or competitors within the supply chain achieve success, it can create mimetic pressure for the company49. Huo (2013) argues that the successful innovation of supply chain partners and the innovation resource advantages within the supply chain can create mimetic pressure for company to adopt innovation strategies50. Therefore, in the context of supply chain safety management, if SMMs perceive that supply chain members (especially collaborators and competitors within the supply chain) gain advantages and success by participating in supply chain safety management, they may experience Mimetic Pressure(MP)51. Normative pressure refers to the shared norms and values that emerge from the interaction and learning among members within a region. These shared norms and values can bring benefits to the organization, thereby exerting pressure on the organization14,15. In the supply chain safety management context, driven by core companies, supply chain members engage in interactions, learning, and cooperation around work safety, creating a unified set of work safety norms and values within the supply chain. These safety norms and values bring benefits such as increased competitiveness or access to resources. Driven by these benefits, SMMs feel pressure to adhere to these norms and values, which is seen as Normative Pressure (NP)29. We refer to this series of pressures arising from supply chain safety management as “Supply Chain Safety Management Pressure (SCSMP).” SCSMP includes CP, MP, and NP.

According to the institutional logic school of new institutionalism, organizations face institutional pressures and seek legitimacy, leading to different Willingness for Responses(WR), including Willingness for Adaptive Responses(WAR) and Willingness for Co-creative Responses(WCR). WAR emphasizes “isomorphism” with existing institutional, manifesting as a responsive intention aligned with the goals of institutional logic isomorphism52,53. Research indicates that in fields dominated by institutional logic, social mechanisms drive organizations to comply with institutional expectations, thereby exhibiting adaptive willingness53. This perspective underscores the constraints of institutional pressure on enterprises, suggesting that adaptive responses are the only option for organizations to gain legitimacy54,55. The literature also notes that, when necessary, groups may punish or expel non-compliant organizations, leading to a convergence of organizational willingness due to this pressure14. From a resource dependence perspective, powerful stakeholders can also influence the acquisition of critical resources, prompting organizations to develop WAR to meet stakeholder demands56,57. In the supply chain, core enterprises occupy resource-advantageous positions, hence, the pressure from these core enterprises influences the decision-making willingness of SMMs58,59. For instance, Ciliberti(2009) found that the procurement standards of large purchasing companies can help suppliers comply with expectations and increase their willingness to implement sustainability policies60. Silva(2020) demonstrated the diffusion paths of core companies’ sustainability strategies within the supply chain, suggesting that institutional pressure for sustainability can enhance suppliers’ willingness to participate61.

Other research suggests that a single isomorphic adaptation mindset cannot explain the widespread phenomenon of differentiated responses. It is proposed that the diversity of organizations and the varied institutional pressures they face increase the complexity of institutional logic, leading to not only adaptive responses but also the emergence of a WCR62,63. This willingness emphasizes the “deconstruction” of existing institutional thinking and represents a desire to create new goals and build new institutions, manifested in a willingness to acquire learning resources and engage in value co-creation64. Some scholars have argued that when facing MP, companies develop a willingness to imitate others and acquire superior learning resources to enhance competitiveness65. Other scholars suggest that NP from shared cognition within institutional fields can potentially influence an organization’s WCR to reshape its identity66. For example, NP from consensus among value chain member companies can encourage these companies to engage in value co-creation67.

Based on the aforementioned literature, it can be inferred that in the context of supply chain safety management, CP, MP, and NP also exist. In response to these pressures, SMMs may develop either WAR or WCR depending on the environment, capabilities, and strategic needs. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

-

H1: SCSMP positively relates to WR.

-

H1.1: CP positively relates to WAR.

-

H1.2: CP positively relates to WCR.

-

H1.3: MP positively relates to WAR.

-

H1.4: MP positively relates to WCR.

-

H1.5: NP positively relates to WAR.

-

H1.6: NP positively relates to WCR.

Theoretical framework of WSB influence based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB)

Categorizing organizational WSB is a prerequisite for exploring the influences on SMMs’ WSB. Most literature on safety behavior classification is still limited to micro-level. Some scholars suggest that employee safety behaviors can be divided into safety compliance behaviors and safety participation behaviors68. safety compliance behaviors refers to actions that individuals must undertake to ensure work safety, whereas safety participation behaviors refers to actions that help increase safety awareness and enhance proactive safety12. Further, some scholars subdivide safety participation behaviors into proactive safety behaviors and pro-social safety behaviors13,69. Pro-social safety behaviors involves voluntary actions employees take to benefit others in exchange for recognition and rewards, while Proactive safety behaviors emphasizes employees’ initiative as a primary attribute in enhancing safety level, highlighting their active efforts to make safety improvements70,71.

Since scholars like Didla et al.(2009) believe that individual behavior is shaped by organizational behavior72. Within the same organizational environment, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises characterized by their small scale and few employees, individual behaviors are often highly consistent40,73,74,75,76. As a result, organizational behavior tends to closely align with managerial behavior due to the high degree of interaction and integration among individuals within these organizations. Managerial decisions and actions are directly reflected in organizational practices and behaviorsl40,73,77,78,79. Additionally, as profit-oriented entities, companies function as both “economic agents” and “social agents” within a broader environment from both economic and sociological perspectives. Their behavior is shaped by a range of factors, including subjective norms and risk awareness.Therefore, the decision-making processes and behaviors observed at the micro-level can be effectively translated to the organizational level40,77,78,79,80,81. Some research has effectively extended the micro-level safety behavior framework to the organizational level9,33,40,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89. Based on these research, this study categorizes the WSB of SMMs into Safety Compliance Behaviors(SCB), Proactive Safety Behaviors(PSB) and Pro-social Safety behaviors(PsSB). SCB refers to actions taken by enterprises to ensure their work safety is legal and compliant. PSB emphasizes the enterprise’s initiative as a key characteristic for enhancing safety, highlighting active efforts made by the enterprise to improve work safety levels. PsSB involves voluntary safety actions taken by enterprises to benefit other organizations, aiming to meet expectations and gain value. From these definitions, SCB can be viewed as fundamental safety behavior, while PSB and PsSB represent more engaged and positive efforts to further enhance safety levels, classifying them as advanced safety behavior.

Scholars often use the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explore behavior of actors, particularly the behavior of micro-level actors90,91,92. Since SMMs are small and have few employees, their decision-making activities are often aligned with those of their managers93,94. Consequently, the use of TPB to explore and predict the behavior of SMMs has increasingly gained attention40,80,95. For example, Li(2023) used the TPB framework to explore the positive impact of subjective norms and intentions on the green development behaviors of construction enterprises81. Wang (2023) based on the TPB framework, empirically tested the impact mechanisms of corporate green technological innovation96. Ali(2023) extended the TPB to investigate the impact mechanisms of corporate sustainable development behaviors73. According to the research paradigm of the TPB, Behavior is influenced by Subjective Norms, Attitudes, Perceived Control, and Behavioral Intention97,98,99. Behavioral Intention refers to actors’ subjective judgment regarding subsequent actions, reflecting their willingness to perform a specific behavior100,101. The concept of this variable is similar to that of the Willingness variable, both referring to a form of inclination and willingness. Therefore, this study combines the two concepts and represents them using the variable Willingness. As a proximal antecedent of behavior, Willingness directly influences the formation of subsequent actions101. From the organizational perspective of SMMs, they also develop relevant intentions and attitudes based on their interests and strategic needs before making decisions102. The process of transforming willingness into consistent behavior is also described as action control. Weiss(2019) studied the transformation of entrepreneurial intention into entrepreneurial behavior103. Guagnano(1995) proposed the “intention - situation - behavior” theory, which posits that environmental protection intentions and situational factors jointly influence individuals’ environmental responsibility behaviors, and situational factors enhance the consistency between intention and behavior104.

Scholars have also explored the relationship between different types of willingness and behavior. For instance, some scholars have discussed the impact of adaptive willingness on behavior. Pang(2022) found that the stronger a company’s adaptive willingness towards environmental regulations, the better its implementation of pollution reduction behaviors105. Newenham-Kahindi&Stevens(2018) discovered that during mergers and acquisitions, acquiring companies develop adaptive willingness to reduce conflicts, which encourages them to learn policies, regulations, and the culture of target companies106. In supply chain quality management and green management, SMMs’ adaptive willingness aligns with responsible behaviors, prompting them to adopt quality compliance behaviors and green behaviors107,108. WAR, representing the willingness for adaptive response to institutions, is also a form of adaptive willingness. Thus, it can be inferred that in the context of supply chain safety management, the WAR of SMMs should positively promote WSB.

Another group of scholars has explored the impact of co-creative willingness on behavior from the perspectives of resource acquisition and value co-creation. Scholars believe that a company’s willingness to acquire resources leads to establishing more dependent and cooperative relationships with other organizations, thereby promoting learning, cooperative, and competitive behaviors109,110,111. For example, Xie& Lv(2018) found that companies in competitive environments develop a willingness to acquire resources, which transforms into competitive behavior through resource advantages112. Do(2021) found that when Vietnamese small enterprises face difficulties, they develop a willingness to acquire resources for creation, further promoting inter-organizational learning and mutual assistance113.

Other scholars have explored the impact of co-creative willingness on behavior from the perspective of value co-creation. Studies suggest that the beneficial outcomes of co-creation activities, such as improvements in environmental protection levels and innovation performance, economically benefit companies and enhance their competitive advantage, thereby promoting more co-creative willingness and translating this willingness into learning and cooperative behaviors64,114,115. Forcadell(2022) research suggests that the stronger a company’s willingness to engage in social value co-creation, the more actions it is to collaborate with other organizations116. WCR, representing the willingness for co-creative response to institutions, is also a form of co-creative willingness. Based on these studies, it can be inferred that in the context of supply chain safety management, WCR should also positively promote WSB. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

-

H2: WR positively relates to WSB.

-

H2.1: WAR positively relates to SCB.

-

H2.2: WAR positively relates to PSB.

-

H2.3: WAR positively relates to PsSB.

-

H2.4: WCR positively relates to SCB.

-

H2.5: WCR positively relates to PSB.

-

H2.6: WCR positively relates to PsSB.

In the research paradigm of the TPB, Subjective Norms are crucial influencing factors. Subjective Norms refer to the external pressure perceived by individuals regarding whether to engage in specific behaviors117,118. Given that the connotation of this variable falls within the scope of Pressure, this study combines it with institutional theory, using the SCSMP perceived by SMMs to represent the external pressures emphasized in Subjective Norms. Based on the above analysis, within the context of supply chain safety management, these perceived SCSMP include CP, MP, and NP.

Scholars have identified CP as a key factor influencing WSB40,118,119. However, these studies mainly focus on CP from the government, lacking attention to supply chain safety management. Some scholars have also discussed the impact of CP from the supply chain management on corporate behavior from a general perspective. For example, Dai(2021) demonstrated that CP from the supply chain management can prompt companies to enhance their behaviors to ensure compliance120. Particularly in quality management, the supply chain’s quality requirements, layered control over suppliers, and internal communication exert supply chain pressure on suppliers, positively influencing their quality decision-making behaviors121,122.

In the realm of social responsibility practices, scholars have also focused on the positive correlation between CP within the supply chain and the social responsibility practices of SMMs21,22. However, some studies have found mixed123,124 or negative correlations94,125. In fact, although most studies emphasize the positive impact of CP within the supply chain, these pressures may also backfire. For example, when companies face resource constraints or difficulties, they may engage in symbolic and passive behaviors10,126.

Although some scholars have acknowledged the existence of MP and NP from the supply chain management29,49,50. systematic research exploring their relationship with the behavior of SMMs is still relatively lacking. More scholars have explored the impact of MP on companies from a general perspective. For example, Hoejmose(2014) argue that MP aims to lead companies to imitate successful businesses16. Therefore, when supply chain members (especially collaborators, competitors within supply chain) gain advantages and success by complying with, implementing, learning, and participating in supply chain work safety management, SMMs may replicate their WSB24,25,127.

NP emphasizes the interaction and learning among organizations within a region, leading to shared norms and values. In the context of supply chain safety management, core companies lead, and supply chain members engage in interaction, learning, and cooperation around work safety, forming similar work safety values, which become NP within the supply chain29. Iatridis (2016) found that under the influence of NP, SMEs may incorporate environmental behaviors into their development strategies128. Hoejmose(2014) suggest that as NP increases, the behavior of SMEs may shift from aiming to improve performance to seeking more sustainable value16. Therefore, in the face of NP from supply chain safety management, SMMs may be willing to adopt certain behaviors to align with the norms and values of the supply chain.

As previously mentioned, past research has provided useful but incomplete explanations of how SCSMP influences the WSB of SMMs. More scholars have focused on the CP form the supply chain management, while neglecting the impact of MP and NP brought by the supply chain management. The multidimensional measurement of SMMs’ WSB makes it possible to distinguish the specificity of each dimension. Previous research has shown that when processes are complex, MP and NP may facilitate the implementation of multidimensional behaviors by companies23,42.Consequently, it can be inferred that, within the context of supply chain safety management, the SCSMP should also positively promote WSB. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H3: SCSMP positively relates to WSB.

-

H3.1: CP positively relates to SCB.

-

H3.2: CP positively relates to PSB.

-

H3.3: CP positively relates to PsSB.

-

H3.4: MP positively relates to SCB.

-

H3.5: MP positively relates to PSB.

-

H3.6: MP positively relates to PsSB.

-

H3.7: NP positively relates to SCB.

-

H3.8: NP positively relates to PSB.

-

H3.9: NP positively relates to PSB.

Another group of scholars posits that Subjective Norms influence Behavior indirectly through Willingness. Representatives of this viewpoint, Fishbein&Ajzen (1975) argue that behavior is determined by Intention, and positive subjective norms help form behavioral Intention97.

Psychologist Tolman also emphasized the mediating role of internal factors in behavior formation, suggesting that a series of factors, including motivation, needs, intention, willingness and perceptions, exist between “external stimulus - behavior”129. This implies that the environment cannot directly determine behavior; instead, external factors must operate through internal factors130,131. Therefore, Willingness cannot be directly equated with Behavior - Willingness plays a crucial role in the transformation of behavior. Scholars have further demonstrated the mediating role of Willingness between the external institutional environment and behavior. For example, Li(2023) explored the mediating role of willingness between subjective norms and green development behavior in construction enterprises81. Tian(2023) investigated the mediating role of green value co-creation willingness between institutional pressure and corporate behavioral performance132. Similarly, Huang(2024) emphasized the mediating role of green value co-creation willingness between market pressure and corporate behavioral performance133.

Although there is no direct literature exploring the mediating role of Willingness in transforming SCSMP into WSB, based on the above studies, it can be inferred that in the context of supply chain safety management, Willingness should also mediate the relationship between SCSMP and WSB of SMMs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H4: WR mediates the relationship between SCSMP and WSB.

-

H4.1: WAR mediates the relationship between CP and SCB.

-

H4.2: WAR mediates the relationship between CP and PSB.

-

H4.3: WAR mediates the relationship between CP and PsSB.

-

H4.4: WAR mediates the relationship between MP and SCB.

-

H4.5: WAR mediates the relationship between MP and PSB.

-

H4.6: WAR mediates the relationship between MP and PsSB.

-

H4.7: WAR mediates the relationship between NP and SCB.

-

H4.8: WAR mediates the relationship between NP and PSB.

-

H4.9: WAR mediates the relationship between NP and PsSB.

-

H4.10: WCR mediates the relationship between CP and SCB.

-

H4.11: WCR mediates the relationship between CP and PSB.

-

H4.12: WCR mediates the relationship between CP and PsSB.

-

H4.13: WCR mediates the relationship between MP and SCB.

-

H4.14: WCR mediates the relationship between MP and PSB.

-

H4.15: WCR mediates the relationship between MP and PsSB.

-

H4.16: WCR mediates the relationship between NP and SCB.

-

H4.17: WCR mediates the relationship between NP and PSB.

-

H4.18: WCR mediates the relationship between NP and PsSB.

Integrated theoretical framework of SMMs’ WSB influences in the context of supply chain safety management

Supply chain safety management is a subset of supply chain social responsibility management. It refers to integrating work safety management elements into supply chain management and implementing a series of measures to enhance safety levels across various stages and members of the supply chain10,11. Supply chain safety management establish an institutional context for SMMs. Scholars have identified three types of supply chain social responsibility management models: “Compliance”, “Collaboration” and “Multi-stakeholder Participation“134,135,136. The “compliance” model emphasizes the use of contractual measures such as behavioral norms, evaluations, and supervision within the supply chain to constrain unethical behavior by suppliers. In this model, SMMs are more likely to experience CP from regulations, audits, and continuous supervision137,138. The “collaboration” model emphasizes improving suppliers’ ethical behavior through assistance and support from supply chain33. The “Multi-stakeholder Participation” model focuses on guiding suppliers to fulfill social responsibility through collaborative mutual aid, investment, and sharing among multiple stakeholders4. In these two models, SMMs experience not only CP but also MP from supply chain partners aiming to gain advantages, as well as NP from unified viewpoints and moral recognition within the supply chain. When considering the different supply chain safety management atmosphere, measures, and varying node positions perceived by each SMMs, the SCSMP they experience become multifaceted and complex139,140. Therefore, exploring the impact of supply chain safety management on SMMs can be approached using the theoretical framework of institutional theory, examining their willingness to respond of SCSMP.

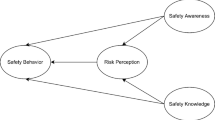

Meanwhile, according to the TPB, the behavior of SMMs is directly influenced by willingness, directly and indirectly influenced by subjective norms, with willingness mediating between subjective norms and behavior97,98,99. Combining this with institutional theory, SCSMP can be regarded as the external pressure emphasized within the concept of subjective norms. Therefore, in the context of supply chain safety management, an “Pressure -Willingness - Behavior” influence pathway can be derived. The CP, MP, and NP from supply chain safety management experienced by SMMs influence their WAR and WCR, which in turn affect their SCB, PSB, and PsSB. Although, according to the TPB, Attitude and Perceived Behavioral Control also play important roles in shaping Intention, this study does not discuss these two factors due to the complexity of the model. In summary, the theoretical model of this study can be illustrated as shown in Fig. 1, which encapsulates the proposed relationships and constructs under investigation.

Method

Ethical considerations

Compliance with Guidelines and Regulations: All methods used in this study were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations to ensure transparency in the research process and the protection of participant privacy and voluntary participation.

Institutional Awareness and Data Anonymity: Although formal approval from an institutional ethics committee was not required, the institution was informed about the study. All data collected were anonymized to protect the identities of participants and ensure confidentiality throughout the research process.

Research design and data acquisition

To ensure validity and reliability, the questionnaire design was based on an extensive review of relevant literature. Due to the paucity of directly relevant scholarly works, this study incorporated established scales for institutional pressures, willingness, and work safety behavior, integrating them with specific challenges identified in supply chain safety management. Preliminary questionnaire drafts were developed through a combination of interviews and literature review, establishing an initial metric.

The questionnaire distribution comprised two phases. Phase one involved distributing questionnaires in Jiangsu and Zhejiang regions starting in May 2023, with initial collection completed by mid-July 2023. The survey yielded 172 responses from a pool of 200 distributed questionnaires. After screening, 134 responses were deemed usable, resulting in an effective response rate of 67%.Subsequently, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to test the appropriateness of this initial scale within the specific context of supply chain safety management. The exploratory factor analysis suggested a suboptimal factor loading for an individual item related to coercive pressure in supply chain safety management. Consequently, this item was excluded, and the remaining items met the preset criteria for analysis. The removal of this item facilitated the formation of the definitive scale for subsequent data collection rounds. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ signifying ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘5’ signifying ‘strongly agree’.

Phase two: Starting in August 2023, the second round of questionnaires was distributed, primarily targeting manufacturing hubs in Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangzhou, and Shanghai, with collection completed by October 2023. To ensure a representative sample, before distributing the questionnaire, we first asked respondents the following question: “Do core enterprises in the supply chain have requirements for the work safety of your company?” Since imposing work safety requirements on suppliers is a fundamental measure of supply chain safety management, respondents who answered “No” were excluded from the survey. These measures helped us filter out non-compliant samples.

Given the survey’s technical subject matter, only enterprise managers or individuals in charge of production safety were eligible as respondents. The study employed both direct and electronic distribution methods, resulting in the issuance of 300 questionnaires and the retrieval of 288, from which 23 were deemed invalid, leaving 265 valid questionnaires for inclusion in the study. Consequently, this resulted in an effective response rate of 88.33%. The demographic and characteristic data of the valid questionnaire respondents are cataloged in Table 1.

Measurements

The SCSMP scale is derived from research by Wang et al. (2018)29, Currás-Pérez et al. (2018)141, Graham (2020)142, Ma et al.(2022)143, and Bhuiyan et al. (2023)144, adjusted appropriately to suit the theme of this study. The SCSMP scale comprises three dimensions: CP, MP, and NP, with a total of 12 items. The WR scale from the research of Bulgurcu et al. (2010)145, Yi & Gong (2013)146, and Kim Sang & Kim Yong (2017)147, and has been modified according to the content of this study. It is divided into two dimensions: WAR and WCR. The WAR includes 3 items, and the WCR comprises 4 items. The scale for WSB comes from the research conducted by Neal & Griffin (2006)68, Testa et al. (2019)148,and Liu et al. (2020)69 which categorizes WSB into three dimensions: SCB, PsSB and PSB. SCB includes 4 items, PSB includes 3 items, and PsSB consists of 3 items. The specific items for each dimension, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, and Composite Reliability (CR) values are shown in Table 2.

In conclusion, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all variables are greater than 0.6, indicating that the scale has good reliability. Additionally, in terms of internal consistency, the CR of each construct of the scale is above 0.7, which confirms that the scale is sufficiently reliable. The AVE values are greater than the threshold value of 0.5, demonstrating that the scale has satisfactory convergent validity.

Tests for common method bias and discriminant validity

Due to the possibility of common method bias in survey research, caused by the method effect of responses coming from the same subject or rater, which can be influenced by same-source bias, it is essential to determine whether the research results are affected by the consistency of the subject. First, Harman’s single factor test is conducted by setting the number of common factors to one. The test reveals that one common factor explains 31.423% of the variance, which is less than 40%, indicating that there is no severe common method bias. Second, the fit of the single-factor structural equation model is assessed, and the model constructed with eight variables has poor fit indices (CMIN/DF = 8.045, RMSEA = 0.163, CFI = 0.429, TLI = 0.385, IFI = 0.432), suggesting that the common method bias in the sample data is not severe. Finally, an eight-factor model is constructed. The model indices are CMIN/DF = 1.134, RMSEA = 0.023, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.988, IFI = 0.990.The eight-factor model fits well, and the fit of the eight factors is better than other factor models, indicating that the variables in the study have good discriminant validity and are distinct, independent constructs.

Data analysis

Model fit test

Before the hypothesis testing with structural equation modeling (SEM), the fit between the model and the data was assessed using AMOS, and the results are presented in Table 3. The ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) is between 1 and 3, RMSEA is less than 0.1, and CFI, IFI, and TLI are greater than 0.9. All these indices have reached their respective standard values, indicating that the model is a good fit.

Direct effect test

Out of 21 direct effect hypotheses tested, the results support 12 of them. Specifically, CP, MP, and NP have a significant positive impact on WAR (β = 0.252, P < 0.001; β = 0.247, P < 0.001; β = 0.204, P < 0.01 respectively); NP has a significant positive impact on WCR (β = 0.265, P < 0.001); WAR and WCR have significant positive impacts on SCB and PSB (β = 0.290, P < 0.001; β = 0.187, P < 0.05; β = 0.222, P < 0.001; β = 0.196, P < 0.01 respectively), and WCR has a significant positive impact on PsSB (β = 0.454, P < 0.001); CP, MP, and NP have significant positive impacts on SCB (β = 0.194, P < 0.01; β = 0.229, P < 0.001; β = 0.194, P < 0.01 respectively), while the other hypotheses are not supported. The specific results of the direct effect test are shown in Table 4.

Mediation effect test

This study explores the mediating roles of WAR and WCR in the relationships between CP, MP, NP, and SCB, PSB, PsSB. Table 5 provides the specific analysis results for the mediation effects. The mediation effect of WAR between CP and SCB, and between CP and PSB is positively significant, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of [0.024, 0.151] and [0.006, 0.127], respectively; the mediation effect of WAR between MP and SCB, and between MP and PSB is positively significant, with 95% CIs of [0.025, 0.146] and [0.006, 0.129], respectively; the mediation effect of WAR between NP and SCB, and between NP and PSB is positively significant, with 95% CIs of [0.015, 0.127] and [0.004, 0.108], respectively; the mediation effect of WCR between NP and SCB, PSB, PsSB is also positively significant, with 95% CIs of [0.021, 0.127], [0.009, 0.131], and [0.047, 0.226], respectively. The hypotheses for the remaining mediation effects are not supported. Figure 2 provides a summary of the results of the hypotheses based on SEM analysis.

Discussion

This research investigates the complex relationship between the SCSMP that SMMs experience from supply chain safety management and their WSB through both theoretical analysis and empirical evidence. The study’s design intricately evaluates the direct influences of CP, MP, and NP on SMMs’ SCB, PSB, and PsSB. Additionally, it examines the indirect effects on these WSBs via the mediating roles of WAR and WCR. Empirically substantiated by data from Chinese manufacturing enterprises, the research not only corroborates the validity of its model and hypotheses but also contributes novel theoretical perspectives and actionable insights into whether and how Supply chain safety management practices can stimulate SMMs towards work safety practices, thereby delineating the mechanisms that underpin WSB. These insights significantly deepen the understanding of SMMs’WSB, with a particular focus on PSB and PsSB. These two behaviors emphasize go beyond the general enforcement of safety contracts. This study also fills the theoretical gap concerning the effectiveness of supply chain safety management.

Theoretical implications

Pressure from supply chain safety management

SCSMP that SMMs experience from supply chain safety management are classified into three distinct types, CP, MP and NP. CP emanates from formalized safety management agreements and regulatory frameworks existing within the supply chain. Empirical evidence suggests that CP significantly enhances SMMs’ WAR and fundamental compliance with safety regulations. Further, WAR serves as a pivotal mediator between CP and SCB, denoting that CP can foster SCB both directly and indirectly. This research substantiates the premise that compulsory safety management directives within the supply chain can markedly elevate the foundational safety behaviors among SMMs. These manufacturers exhibit a propensity to fulfill essential work safety duties and adhere to basic contractual requirements. Nonetheless, the influence of CP on more advanced safety behaviors, including PSB and PsSB, is minimal. This infers that under CP, SMMs might limit their actions to mere conformity with regulations, without extending efforts voluntarily to advance safety standards. Hence, while CP is capable of guiding SMMs towards regulatory compliance, its role in inciting a more profound, self-driven enhancement in safety practices remains constrained.

MP derives from the exemplary safety practices observed among partners or rivals within the supply chain. Research findings indicate that such MP exerts a pronounced positive influence on SMMs’ SCB, with WAR serving as a significant mediator in this dynamic. This implies that SMMs are predisposed to replicating established safety protocols. Nonetheless, the role of MP in nurturing the evolution of PSB and PsSB is found to be unsubstantial. This reveals that when subjected to MP, SMMs are prone to choosing concrete, regulation-sanctioned basic safety compliance practices over the more nebulous, intrinsically-motivated advanced safety activities. The propensity to prioritize visible and validated safety measures suggests that MP facilitates adherence to safety norms but does not inherently inspire a transition to voluntarily, proactive, and cooperative safety initiatives.

NP originates from the collective ethos and work safety values that pervade the supply chain. Studies have substantiated that this form of pressure has both a direct and an indirect substantive impact on SCB among SMMs. This denotes that a pervasive culture of safety norms can channel SMMs’ behaviors towards heightened compliance. Concurrently, NP also indirectly influences PSB and PsSB via the conduits of WCR. This also underscores that an enriched practice of supply chain safety management, coupled with heightened involvement of SMMs in these practices, can foster more coherent and mature work safety values. In turn, this can further stimulate SMMs’ receptiveness towards supply chain safety management practices, thereby facilitating the emergence of more advanced work safety behaviors. This includes taking the initiative to enhance the standards of work safety, as well as actively engaging in the exchange and collaboration on work safety with enterprises within the supply chain, among other actions.

The empirical conclusions validate the interplay between SCSMP and WSB. In essence, confronted with pressures from safety management within the supply chain, SMMs—driven by survival instincts and competitive enhancement—are more inclined to adhere to contractual obligations and operationalize fundamental SCB. However, the capacity of institutional pressure to catalyze enterprises carry out PSB and PsSB is restricted. Mediation effect test revealed that the WR is crucial in stimulating PSB and PsSB. CP, MP and NP all exert a positive influence on SMMs’ WAR, while NP induces a favourable response towards WCR among SMMs. This observation implies that a more robust array of safety management practices within the supply chain coupled with diversified pressure sources can evoke a cooperative attitude in SMMs towards supply chain safety management mechanisms. It further exhorts supply chain leaders and decision-makers to engineer more inducement mechanisms to encourage SMMs to transition towards an embrace of supply chain safety management. Future inquiries should specifically concentrate on achieving equilibrium among multiple types of institutional pressures, kindling co-creative willingness within enterprises, and catalyzing a transition in SMMs from basic compliance behaviors towards a vast and proactive spectrum of superior safety behaviors. Particularly in the context of supply chains, special attention should be given to how a mature supply chain safety culture and values can be formed through the leadership of core enterprises, resulting in a voluntary, active, and cooperative actions across the entire supply chain.

Willingness for response (WR) of SMMs

This research enhances the comprehension of the WR, encompassing two distinct dimensions, the WAR and the WCR. WAR is a form of isomorphic responsiveness, indicating the ability of SMMs to sustain adaptation and cooperation in the face of supply chain safety management. WCR is a form of deconstructive responsiveness, capturing the aspiration of SMMs for collective growth and active innovation in association with supply chain safety management. By conducting an in-depth analysis of the role of WR in the relationship between SCSMP and WSB. This study presents novel theoretical implications, extending existing literature with a unique perspective and insights.

This study has been ascertained that SMMs generally demonstrate the WAR when confronting pressures stemming from three distinct dimensions. WAR is the immediate reaction of SMMs to the SCSMP, mirroring the crucial competence needed to ensure that their behaviors align with the expected standards.The findings of this investigation underscore the critical function of WAR not merely in transforming rudimentary SCB but also in facilitating the evolution to PSB. This further suggests that the WAR of SMMs not only entails adjustments to the prevailing environment but also involves the anticipation and readiness for potential future shifts. The WAR is not static, it evolves with practice and environmental changes. This paradigm shift in understanding offers a new theoretical perspective for comprehending and enhancing the WAR of SMMs. It indicates that SMMs should possess not only a robust capability to adapt to the current environment but also the foresight to anticipate future changes, prepare in advance, and face challenges with a forward-looking ability.

Secondly, data analysis reveals that the WCR acts as a vital mediating factor in the transmutation of NP into SCB, PSB, and PsSB. This illustrates that the WCR exerts a more positive influence compared to the WAR. It suggests that when confronted with pressures, SMMs do not merely conform to their surroundings but also evolve and innovate collaboratively within the environment. The inclination towards WCR is intimately correlated with PSB, substantiating that by fostering the WCR among SMMs, it can stimulate SMMs to actively engage in the standard and norms establishment process, collectively mold the supply chain’s safety culture with core enterprises, and co-develop shared work safety technologies for the supply chain. The WCR is tightly intertwined with PsSB, which reinforces the notion that the WCR not only impels SMMs to elevate their own safety standards but also motivates these enterprises to partake actively in measures designed to ameliorate the safety practices and milieu within the supply chain network. In the sphere of safety management, the responsiveness of SMMs is intricately linked to their intrinsic capabilities. This connection implies that to trigger SMMs towards showcasing multi-dimensional, advanced work safety behaviors, there is a requisite for simultaneously harboring both WAR and WCR. This notion accentuates the critical role of organizational dynamic capabilities.

The aforementioned study corroborates that by intensifying the dual willingness of SMMs to engage with supply chain safety management systems, we can profoundly incite higher-tier work safety behaviors among SMMs, consequently elevating the overall work safety standards across the entire supply chain. Simultaneously, we suggest that the WAR extends beyond a singular dimension of complying with the existing state of affairs and is, in fact, a potent dynamic system that encapsulates the anticipation of future shifts. WAR doesn’t just guarantee adherence to safety protocols among SMMs, but also underlines their intent to devise strategies for future progression while concurrently preserving current stability. WCR emphasizes more on the positive interaction and mutual progress between SMMs and their environment. WCR indicates that SMMs possess the zeal and capability to engage in the establishment of supply chain safety standards, co-innovation of technology, and co-construction of a safety culture, thereby driving the enhancement of the overall safety atmosphere and standards within the supply chain. This process demands not just the dedication of individual enterprises but also calls for widespread collaborative effort and a shared consensus among all entities throughout the entire supply chain. In conclusion, both WAR and WCR are important. By integrating these dual intentions, SMMs can not only ensure regulatory safety management, but also advance towards more promising innovative safety management. Such an approach not only aids in promoting the perpetual refinement of safety practices among SMMs but also advances the development of the safety management framework throughout the entire supply chain.

Work safety behavior (WSB) of SMMs

This research probes into the selection of WSB by SMMs under the impetus of supply chain safety management. The WSB encompass SCB, PSB, and PsSB. SCB is a basic compliance behavior, reflecting the capability of SMMs to stick to fundamental safety contracts under the stress of supply chain safety management. Compared to SCB, PSB and PsSB are go beyond the general enforcement of safety contracts, emphasizing voluntary, proactive, and cooperative actions by companies. The inception of these activities necessitates a mediation transformation involving WAR and WCR. Understanding the influence pathways of WSB aids in theoretical expansion concerning the impact of complex behaviors within enterprises.

Firstly, SCB not only as a response from SMMs towards supply chain safety production rules and contracts, but also serves as a direct reflection of the maturity level of in-house work safety. Only with a robust foundation in basic safety behaviors can SMMs effectively guard against potential risks, serving as the cornerstone for advanced safety behaviors. Data analysis reveals that SCB originates from the direct effects of SCSMP and the mediating transformation of WR. This indicates that the establishment of a comprehensive supply chain safety management system framework is of paramount importance and is the key to ensuring that SMMs fulfill their safety production contracts. This includes the development of detailed work safety compliance standards for suppliers, a thorough supplier safety inspection regime, and an effective reward and penalty system. At the same time, there should be an emphasis on invigorating the SIRW, thereby enhancing the SMMs to progressively develop work safety behaviors that are in accordance with the expectations of the supply chain.

Secondly, PSB demonstrate the conduct of SMMs towards active risk prevention and continuous improvement. By employing early warning systems, engaging in preventive actions, and implementing responsive measures, SMMs can significantly mitigate the occurrence of accidents. However, such behaviors exceed the scope of contractual obligations. SCSMP cannot directly influence the emergence of these behaviors. Instead, the transformation requires mediation through WR. This indicates that there is not only a need for further enhancement of the supply chain safety management system but also for the supply chain to engage in cross-departmental and cross-hierarchical coordination efforts. Such efforts are pivotal in creating a conducive atmosphere for supply chain safety management. By doing so, it fosters the WR and thereby promotes the proactive participation of SMMs in safety practices.

PsSB represents a behavioral paradigm within which SMMs exhibit social responsibility, both within their organizations and in external interactions. Such behavior not only has the potential to enhance collaboration and relationships among SMMs but also aids in setting a positive precedent for work safety within the supply chain. The PsSB can effectively drive the enhancement of safety levels within other enterprises in the supply chain, achieving the safety and harmonious development of the entire supply chain. Data analysis reveals that PsSB is mediated by the WCR in response to NP. This suggests that a shared safety culture and value system within the supply chain play a critical role in fostering PsSB. The supply chain can orchestrate and promote mutual trust and cooperation among enterprises within the chain, fostering a collaborative culture of safety. SMMs should also demonstrate their safety strengths to other supply chain members, setting an exemplary role model. This initiative motivates the entire supply chain to pursue higher safety standards, leading to collaborative success and shared benefits.

To sum up, the mutual deepening of theory and practice provides a broad perspective for further understanding the work safety behavior of SMMs. From internalizing SCB, stimulating PSB, to expanding the dimensions of PsSB, this process not only enriches our understanding of WSB but also offers action guidelines for future management practices.

Practical implications

Inspired by the aforementioned theories, it is imperative at the practical level to formulate more comprehensive and flexible policies for supply chain safety management. Simultaneously, attention should be paid to the transition in the WR. These manufacturers should be encouraged to adopt more proactive and prosocial safety behaviors while maintaining baseline safety compliance.

Firstly, a systematic supply chain safety management system should be established to ensure the fundamental safety compliance behavior of SMMs. It is essential for supply chains to establish a systematic and standardized supplier safety management system. This system should enhance oversight of suppliers’ work safety standards, intensify supplier work safety training, and improve suppliers’ work safety capabilities. SCB should be internalized as intrinsic behaviors and self-regulation within SMMs. This ensures that the contractual safety standards of the supply chain are stringently upheld throughout the entire production process of SMMs.

Secondly, an affirmative supply chain safety culture atmosphere should be fostered to stimulate the WR. The supply chain should enhance cross-departmental and cross-hierarchical coordination to foster a robust supply chain safety management system, safety culture and safety atmosphere. Effective incentive mechanisms and feedback pathways should be designed to reward SMMs that take the initiative to improve their work safety levels. By stimulating and developing the WR, this process would increase the awareness and motivation of all chain enterprises to actively participate in supply chain safety management, thus fostering higher-order work safety behaviors in SMMs.

Thirdly, the NP of supply chain safety management and the WCR of SMMs should be strengthened to encourage the cultivation of PsSB. The generation of NP originates from the formation of shared values within the supply chain, highlighting the necessity to shape these values through systematic supplier safety training and the creation of a safety management culture atmosphere. In acknowledging the safety philosophy of the supply chain while fulfilling social responsibilities, it aims to stimulate a positive contribution from SMMs towards the overall safety environment of the supply chain and reinforce its co-creative willingness. The supply chain should build collaborative relationships with multiple entities and invite SMMs to actively participate in the construction of common safety technologies and safety management systems. This co-participation encourages a transition of safety behaviors in SMMs from internal to external, thereby culminating in higher-order work safety behaviors.

Conclusion

This research emphasizes that the enhancement of safety levels in SMMs requires not just foundational SCB but also initiating PSB and PsSB. This paradigm shift infuses new vitality into the study and practice of corporate work safety behavior, also underscoring the active and dynamic nature of these behaviors. The research findings suggest that SCSMP is the key factor in shaping the WSB. The WR serves as a vital bridge linking external pressures and internal behaviors.

Specifically, although CP, MP and NP all contribute to ensuring the basic SCB of SMMs, their direct promoting effects on stimulating PSB and PsSB are limited. This calls for further strategies and incentive mechanisms. Through the investigation into the WAR and WCR, we have identified these elements as critical for SMMs to form PSB and PsSB. WAR, as an integral part of isomorphic willingness, is not merely about conforming to the status quo on a single dimension. It does not only ensure the SCB, but also reveals the intention of SMMs to form future development strategy transitions while balancing current stability. WCR, as a form of deconstructive willingness, emphasizes a more active interaction and mutual progress between SMMs and their environment. By stimulating the dual response willingness of SMMs, it not only facilitates compliance-based safety management but also motivates them towards more promising innovative safety management practices.

Thus, the research conclusions underscore a theoretical implementation path that continuously refines the supply chain safety management context, stimulates the dual response willingness of SMMs, and strengthens interaction and collaboration between supply chain enterprises to comprehensively elevate work safety behaviors. In the practice of improving the overall safety level of the supply chain, this study advocates for the formulation of more comprehensive and flexible supply chain safety management policies. These policies should encompass not only adherence to rigid regulatory compliance but should also encourage collaboration in building a safety culture and safety atmosphere within the supply chain. By fostering continual learning and innovation, the entire supply chain network can collectively raise safety standards and efficiency. Moreover, it is essential to pay attention to the WR shift. There is a need to motivate SMMs to adopt more positive measures while maintaining baseline compliance with safety regulations.

Limitations and future prospects

The context of supply chain safety management is constantly evolving, as are the work safety behaviors of SMMs. Constrained by data validity, this study has the following two limitations, Firstly, the sample selection is limited. This study uses a sample of 265 SMMs within the supply chain, with the principle of selection being whether supply chain safety management has been implemented in their respective supply chains. The study did not differentiate between industrial characteristics and regional features, nor did it distinguish between suppliers within a single supply chain or those across multiple supply chains. Future research could expand the sample selection to enhance the characteristics of the data.

Secondly, not all influencing factors were considered. While this study has identified the significant roles of SMMs’ WAR and WCR, and elucidated the impacts of SCSMP from various dimensions on WSB, it failed to encompass all possible factors impacting WSB, such as corporate culture and technological capabilities. Future research could incorporate additional influencing factors to enrich the research context.

Furthermore, as practices in supply chain safety management continue to improve, future research could involve ongoing monitoring of the implementation effectiveness and efficacy of supply chain safety management to investigate different strategies. In summary, while this study offers unique insights and theoretical contributions, the limitations identified and potential directions for future research underscore the importance of continued exploration in the field of supply chain safety management.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- SCSMP:

-

Supply chain safety management pressure

- CP:

-

Coercive pressure

- MP:

-

Mimetic pressure

- NP:

-

Normative pressure

- WR:

-

Willingness for responses

- WAR:

-

Willingness for adaptive responses

- WCR:

-

Willingness for co-creative responses

- WSB:

-

Work safety behavior

- SCB:

-

Safety compliance behavior

- PSB:

-

Proactive safety behavior

- PsSB:

-

Pro-social safety behavior

References

Fontana, E. & Egels-Zandén, N. Non Sibi, Sed Omnibus: Influence of supplier collective behaviour on corporate social responsibility in the Bangladeshi Apparel Supply Chain. J. Bus. Ethics. 159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3828-z (2019).

Huq, F. & Stevenson, M. Implementing socially sustainable practices in Challenging Institutional contexts: Building theory from seven developing country supplier cases. J. Bus. Ethics. 161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3951-x (2020).

Gomes, S., Pinho, M. & Lopes, J. M. From environmental sustainability practices to green innovations: evidence from small and medium-sized manufacturing companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2657 (2023).

Talbot, D., Raineri, N. & Daou, A. Implementation of sustainability management tools: The contribution of awareness, external pressures, and stakeholder consultation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag.28. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2033 (2020).

Zhou, M., Long, X. & Govindan, K. Unveiling the value of institutional pressure in socially sustainable supply chain management: The role of top management support for social initiatives and organisational culture. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag.31(4), 2629–2648. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2710 (2024).

Mani, V. & Gunasekaran, A. Four forces of supply chain social sustainability adoption in emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ.199, 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.02.015 (2018).

Mani, V., Gunasekaran, A. & Delgado, C. J. Enhancing supply chain performance through supplier social sustainability: An emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ.195, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.10.025 (2018).

Rachel, A. Emerging roles of lead buyer governance for sustainability across global production networks. J. Bus. Ethics. 162, 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04199-4 (2020).

Zhou, Q., Mei, Q., Liu, S., Zhang, J. & Wang, Q. Driving mechanism model for the supply chain work safety management behavior of core enterprises—an exploratory research based on grounded theory. Front. Psychol.12, 807370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.807370 (2022).

Baden, D., Harwood, I. & Woodward, D. G. The effects of procurement policies on ‘downstream’ corporate social responsibility activity. Int. Small Bus. J.29, 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610375770 (2011).

Wilhelm, M. M., Blome, C., Wieck, E. & Xiao, C. Implementing sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: Strategies and contingencies in managing sub-suppliers. Int. J. Prod. Econ.182, 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.08.006 (2016).

Wang, D., Wang, X., Griffin, M. A. & Wang, Z. Safety stressors, safety-specific trust, and safety citizenship behavior: A contingency perspective. Accid. Anal. Prev.142, 105572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105572 2020).

Arefin, M. S., Roy, I., Chowdhury, S. & Alam, M. S. Employer safety obligations, safety climate, and safety behaviors in the ready-made garment context in Bangladesh. J. Saf. Res.83, 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2022.08.020 (2022).

Dimaggio, P. & Powell, W. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev.48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101 (1983).

Song, B. & Zhao, Z. Institutional pressures and cluster firms’ ambidextrous innovation: the mediating role of strategic cognition. Chin. Manag. Stud.15(2), 245–262 (2021).

Hoejmose, S., Grosvold, J. & Millington, A. I. The effect of institutional pressure on cooperative and coercive ‘green’ supply chain practices. J. Purchasing Supply Manag.20, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.07.002 (2014).

Meixell, M. J. & Luoma, P. Stakeholder pressure in sustainable supply chain management: a systematic review. Int. J. Phys. Distribution Logistics Manage.45(1/2), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0155 (2015).

Stekelorum, R. The roles of SMEs in implementing CSR in supply chains: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Logistics Res. Appl.23, 228–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2019.1679101 (2020).

European Commission. Responsible Entrepreneurship: A Collection of Good Practice Cases among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises across Europe (Official Publications of the European Communities, 2003).

Li, N., Toppinen, A. & Lantta, M. Managerial perceptions of smes in the wood industry supply chain on corporate responsibility and competitive advantage: Evidence from China and Finland. J. Small Bus. Manage.54, 162–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12136 (2016).

Baden, D., Harwood, I. & Woodward, D. G. The effect of buyer pressure on suppliers in SMEs to demonstrate CSR practices: An added incentive or counter productive? Eur. Manag. J.27, 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.10.004 (2009).

Lee, H. Y., Kwak, D. W. & Park, J. Y. Corporate social responsibility in supply chains of small and medium-Sized enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag.24, 634–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1433 (2017).

Marculetiu, A., Ataseven, C. & Mackelprang, A. W. A review of how pressures and their sources drive sustainable supply chain management practices. J. Bus. Logistics. 44, 257–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12332 (2023).

Fontana, E., Atif, M. & Sarwar, H. Pressures for sub-supplier sustainability compliance: The importance of target markets in textile and garment supply chains. Bus. Strategy Environ.33(5), 3794–3810. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3680 (2024).

Xu, N., Huo, B. & Ye, Y. The impact of supply chain pressure on cross-functional green integration and environmental performance: An empirical study from Chinese firms. Oper. Manag Res.17, 612–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-024-00439-7 (2024).

Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132 (2008).

Laguir, I., Staglianò, R. & Elbaz, J. Does corporate social responsibility affect corporate tax aggressiveness? J. Clean. Prod.107, 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.059 (2015).

Chassé, S. & Courrent, J-M. Linking owner–managers’ personal sustainability behaviors and corporate practices in SMEs: The moderating roles of perceived advantages and environmental hostility. Bus. Ethics: Eur. Rev.27, 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12176 (2018).

Wang, S. Y., Li, J. & Zhao, D. T. Institutional pressures and environmental management practices: The moderating effects of environmental commitment and resource availability. Bus. Strategy Environ.27https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1983 (2018).

Wang, M. M. & Zhang, G. C. What motivates firms to adopt a green supply chain and how much does it matter? Front. Environ. Sci.11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1227008 (2023).