Study on static in-situ curing characteristics of CFRP based on near infrared laser

The quick curing method of carbon fibre reinforced plastics (CFRP) is one of the hotspots in current research. A static in-situ curing method for CFRP prepreg based on near-infrared laser was put forward in this study. The in-situ curing structural characteristics and the mechanism of CFRP were investigated through real-time surface temperature measurement, COMSOL temperature field simulation, 3D measurement of curing morphology and resin curing degree test. The thermal conductivity of the CFRP along the fiber direction is considerably higher than that along the perpendicular fiber direction. As a result, the temperature profile in the plane takes on an elliptical shape. During the transfer, the temperature field gradually decreases, resulting in an ellipsoidal 3D high-temperature distribution. The different shrinkage phenomena in the different curing regions between the layers lead to an irregular ellipsoidal solidification morphology of the unidirectional CFRP. The temperature in the center of the heat affected zone increases as a power exponential function with time. The area and depth of the heat-affected zone increases with the laser power, and the curing area is positively correlated with the degree of curing. As a result, curing temperature governing equations based on laser power and layer thickness have been proposed, while relationship equations based on laser power, curing depth and curing morphology have been developed. In addition, prediction equations based on curing morphology have been developed for curing degree, in order to achieve precise curing of CFRP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon fibre reinforced plastics (CFRP) is a high-performance material with resin as the matrix and carbon fiber or its braid as the reinforcement1. Since the advent of CFRP, due to its high specific strength and specific modulus, excellent high temperature and corrosion resistance, strong design ability and a series of advantages2, it has been widely used in aerospace, automotive industry, wind turbine blades3,4,5 and other fields.

The curing method of CFRP has a profound effect on its performance. The commonly used curing method of CFRP is autoclave curing, which has a long curing cycle and high energy consumption. The component size is also limited by the size of autoclave and the forming process6,7,8. In order to optimize the curing process, new curing methods which includes electron beam curing, gamma ray curing, X-ray curing and microwave curing have been developed9. However, these new curing methods all have irremediable shortcomings. For example, composites cured by electron beam have weak interfacial binding force between fibres and matrix materials, and poor transverse mechanical properties10. Laser-cured light sources have high flexibility, less energy consumption during curing, fast curing speed, and high curing accuracy. Therefore, laser curing is expected to appear as a new and efficient curing method for composite materials11.

There are three kinds of lasers in the industry—ultraviolet laser, visible laser and infrared laser12,13. Ultraviolet lasers offer the advantages of high production efficiency, environmental protection in the production process, and small equipment space. However, the UV laser has an effect on the curing system by exciting the light-sensitive material, and its dependence on the light-sensitive material limits its use in composite materials. Visible optical lasers are mostly the result of nonlinear frequency conversion of near-infrared lasers. Poor beam quality and high cost limit their application in laser curing. Infrared lasers, which cure composite materials mainly through thermal effects, have been more widely used in the composite materials field due to their more extensive matching and better laser quality compared to ultraviolet lasers and visible lasers. At the same time, industrial mid-infrared lasers can be classified into long-range, mid-infrared and near-infrared lasers based on the laser wavelength. Near-infrared laser has short wavelength, deeper penetration in composite materials, and larger processing volume, making it more valuable than other wavelength infrared laser in the field of curing composite materials14,15,16,17.

Curing of resin-matrix composites is dominated by resin curing and laser-induced resin curing is mainly used in stereolithography. Jardini et al.18,19 showed that the volume shrinkage rate of the resin after infrared laser curing was extremely low, which could improve the spatial resolution of the cured resin and realize the local curing of the resin. In addition, laser light can shorten the curing time of the resin. The study by Mandic et al.20 showed that laser not only improves the curing rate of resin, but also shortens the time when the maximum curing rate begins. Schmitz et al.21 applied near-infrared laser to the preparation process of resin coatings, which considerably shortened the curing time compared to traditional oven technology. The above studies show that laser technology is an effective way to improve the resin curing process.

Lasers have been used in the preparation of composite materials. Kumar et al.22 used infrared laser to shorten the curing time of glass fibre reinforced plastics (GFRP). Wang et al.23 observed that there was more fibre adhesion resin in infrared laser cured GFRP, and this process led to co-curing of the resin inside and outside. While improving the homogeneity of the material, it also strengthens the material. Wu et al.24 successfully prepared Zr–Al–Ni–Cu metal glass composites by using laser rapid prototyping technology. In addition, some researchers have used laser-induced graphene generation in composite materials and monitored the structure of composite materials through graphene. Cheng et al.25 used near infrared laser to directly generate laser-induced graphene on the surface of aramid fabric. Groo et al.26 integrated laser-induced graphene layers into the interlaminar region of glass fibre reinforced composites, realizing the function of monitoring the strain and damage of glass fibre reinforced composites. Laser-induced curing of composites is a process of light absorption and heat conduction. Chern et al.27,28 showed that, compared to glass fibre/epoxy resin matrix composites, the stronger absorption performance of infrared laser in carbon fibre/epoxy composite makes CFRP more suitable for laser curing than GFRP. The surface adhesion of carbon fibre and resin layer can be realized at about 100℃.

The main applications of lasers in CFRP are surface treatment, heterogeneous welding, and damage repair. Xie et al.29 used a laser engraving machine with the highest power of 20 W to etch the surface of carbon fibre laminate, which showed that spot distance, scanning angle and pattern of laser beam affect laser processing performance. Xia et al.30 used 700 W power laser to make the joint surface of DP590 and carbon fibre composite material achieve a temperature of 335℃, and the two materials were successfully welded to get the best performance. Wang et al.31 took advantage of the fast curing speed of laser and applied it to the rapid repair process of carbon fibre composite materials. It has been shown that although increasing the speed of the laser motion decreases the maximum temperature, the average temperature can rise within a certain range.

Studies of laser in resin curing and composite curing have demonstrated the application value of laser curing. Lasers have also been used for CFRP processing. However, there is relatively little research on laser curing in the CFRP field. Local curing is one of the advantages of laser curing, so the static in-situ curing mechanism of near infrared (NIR) lasers in CFRP preconditioners is investigated in this study. A near-infrared laser beam is irradiated on the surface of the CFRP preconditioner, passes through the light-transmitting resin and is absorbed by the light-absorbing carbon fibre. The carbon fibre converts the optical energy absorbed from the laser beam into thermal energy, which is then transferred to the surrounding resin via thermal conduction. The resin melts and seeps into the pores surrounding the carbon fibre. The curing of composite materials is completed through the diffusion and entanglement of resin molecular chains32. A laser curing platform was constructed, and the influence of different power laser on the temperature field of laser beam irradiation region, the morphology and curing degree of CFRP prepreg region were studied and analysed by irradiating near infrared laser of different power to unidirectional carbon fibre prepreg in the same direction. The experimental results of this study reflect the curing law of NIR lasers in CFRP preconditioners and can provide guidance for surface curing of composite materials, mobile laser source-assisted curing, local damage repair, laser welding and other technologies.

Materials and methods

Materials and equipment

The material used in the experiments is TORAY T700 12 K prepreg, which is based on epoxy resin and has 60% fiber volume content. The CFRP prepreg was made into a specimen with a size of 20 × 20 mm, with a ply direction of 0°.

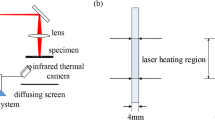

The CFRP laser curing platform included an 808 nm infrared laser, an infrared thermometer and other parts as shown in Fig. 1. The infrared laser wavelength used in the experiment is 808 nm, the spot diameter is 2 mm, and the maximum power is 5 W. During the laser curing experiment, the distance between the laser lens and the CFRP sample was determined to be 300 mm, and the experiment was carried out in the air at an ambient temperature of 24-26℃. The laser is irradiated vertically into the center of the target, and the infrared thermal imager synchronously measures the temperature. Therefore, after curing process, each layer is observed.

CFRP structures and process parameters utilized in this study are shown in Table 1. On this basis, real-time surface temperature measurement, temperature field simulation, 3D curing morphology measurement and resin curing degree measurement were carried out. In other to study the influence of material structure on real-time surface temperature in regards to the point temperature analysis of the target material, four kinds of layup thicknesses were set for the prepreg namely; two layers, four layers, eight layers and 16 layers. To better investigate the influence of laser power, when studying the morphology and performance characteristics of the target material after curing, the number of prepreg layers was only set as eight layers.

Simulation modeling of near-infrared laser and CFRP interaction process

The process of laser action on CFRP is extremely complex, and it is difficult to know the internal temperature field distribution of the material by using the traditional experimental method, so the internal temperature field distribution of CFRP is investigated with the help of finite element analysis software COMSOL. In the simulation process, a Gaussian heat source is used to replace the laser energy, and the CFRP is simplified to a homogeneous single model, ignoring the inhomogeneous distribution of carbon fiber and epoxy resin.

Heat source modeling

When the laser acts on the surface of the CFRP material, the energy is mainly absorbed by the surface of the material, so the energy transfer process from the laser to the surface of the material can be regarded as the loading process of the surface heat source. The distribution of the laser energy is Gaussian, so a Gaussian heat source can be used to replace the near-infrared laser heat source in the finite element simulation. According to Gaussian, distribution characteristics can be obtained as the heat flow density equation which is:

Geometric model

Considering the simulation and experimental requirements, the size of the model is determined as 20 × 20 × 1 mm. In order to take into account the computational accuracy and computational efficiency, the analysis result region is divided into a large number of finite size quadrilateral meshes.

Material model

As shown in Fig. 2, the process of laser curing CFRP involves many aspects such as laser heating, heat conduction of carbon fiber and epoxy resin curing. First of all, in the process of laser curing, the laser will irradiate the surface of the CFRP, and the laser energy is absorbed and converted into heat energy, which will cause the surface temperature of the material to rise, forming a heat source. Secondly, as the laser energy is absorbed, the heat will be transferred to the inside of the material. Since carbon fiber has good thermal conductivity, the heat will be passed into the resin matrix along the direction of the fiber. Finally, this local heating will promote the cross-linking reaction of epoxy resin, so that the CFRP material can be locally cured.

It can be seen that the microstructure changes of CFRP after laser heating are very complex, including a large number of fiber and matrix resin arrangement and organizational changes. The establishment of the representative volume element (RVE) can simplify the complex microstructure into a small and accurate volume unit, thus reducing the complexity of the model and facilitating the subsequent numerical simulation.

A thermal transfer simulation model of the interaction between the NIR laser and the CFRP was constructed in the COMSOL software to calculate the 3D temperature field. The thermal conductivity of CFRP exhibits anisotropy, with a considerably higher thermal conductivity in the direction of the fiber compared to the perpendicular orientation to the fiber direction. Also, carbon fiber and epoxy have different properties. Therefore, based on the RVE model, the mixing rule is used to design the thermal model. The temperature field model for laser curing of CFRP is mainly composed of density. \(\:{\uprho\:}\), specific heat capacity C, and thermal conductivity \(\:{\uplambda\:}\). In the mixing rule, the density and specific heat capacity of the CFRP can be approximately treated as isotropic in comparison to the thermal conductivity, which can be expressed by Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively:

Where \(\:{\phi\:}_{f}\), \(\:{\phi\:}_{p}\), \(\:{\rho\:}_{f}\), \(\:{\rho\:}_{p}\), \(\:{C}_{f}\) and \(\:{C}_{p}\) are the volume fraction, density and specific heat capacity of carbon fiber and resin, respectively.

The thermal conductivity of CFRP has a pronounced anisotropy, which can be represented by Eqs. (4) and (5):

Where \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{x}}\) and \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{y}}\) are equivalent thermal conductivity in parallel fiber direction and vertical fiber direction, respectively; \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{f}\text{x}}\) and \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{f}\text{y}}\) are thermal conductivity of carbon fiber in parallel fiber direction and vertical fiber direction respectively; \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{p}}\) is thermal conductivity of resin matrix.

The main thermo-physical property parameters of CFRP materials are set as shown in Table 2.

Analysis method

To explore the in-situ curing mechanism of CFRP, it is necessary to analyze the temperature field distribution after CFRP absorbs laser energy. In order to compare the difference of heat conduction along the fibre direction and perpendicular to the fibre, the CFRP composite material with unidirectional 0° layer was used as the research object. The infrared thermal imager receives the infrared radiation emitted by the interaction of the laser and the CFRP through the optical system. The received infrared radiation is converted into an electrical signal by an infrared detector. The electrical signal is amplified and converted to produce temperature information, allowing the temporal variation pattern of the laser irradiated center temperature and the effect of laser power on the surface temperature field distribution of the CFRP to be studied.

After the completion of laser irradiation, the MV-CS200-10GC industrial camera was utilized for measurement of morphology and curing area of each layer of CFRP material. The impact of laser power on the characteristics of CFRP curing was compared and analyzed.

The curing degree for thermosetting polymers can be determined using a differential scanning calorimeter, which is ramped from 0 °C to 250 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. By analyzing the heat release curve, the curing degree of each layer in an eight-layer CFRP material under different laser power conditions can be calculated using the following formula.

where, α is the degree of curing, while ΔH0 and ΔHR are the total heat and waste heat of the complete exothermic reaction, respectively.

Results and discussion

Temperature distribution characteristics during heating

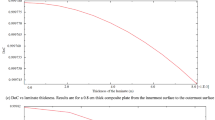

The temperature of the central point of the laser irradiation, which is caused by near-infrared laser energy, directly affected the in-situ curing behavior of CFRP. As shown in Fig. 3, the temperature rose sharply at the initial moment since the carbon fibre on the surface continuously absorbs laser energy during the laser irradiation process. But the growth slowed down as time progressed until it finally flattened due to the reduction of thermal transmission.

The temperature and heating rate of the carbon fibre prepreg were controlled by adjusting laser power and CFRP thickness. The surface temperature at the point of laser irradiation over time can be mathematically modeled as a power function as follows:

where, T is the surface temperature, t is the time, w is the power of the laser and h is the thickness of the CFRP prepreg. n is an independent constant. k, w0, and m are functions of laser power and CFRP thickness.

Therefore, after parameter fitting, the surface temperature curves can be calculated as follows:

Calculated results are quite close to experimental results as shown in Fig. 3. It can be seen that the formula can be used to design the in-situ curing heating parameters of CFRP prepreg and control the curing process.

Based on the homogeneous model of CFRP, the upper surface temperature field distribution diagram of unidirectional CFRP material at the end of laser irradiation (60s) was obtained in the simulation study, and synchronous experimental research was conducted on the result, as shown in Fig. 4. For carbon fiber, the axial thermal conductivity is much higher than that of the radial, resulting in the axial thermal influence distance being much greater than the radial thermal influence distance in the unidirectional structure of CFRP material. As a result, its temperature distribution is elliptical. The temperature near the center of the laser irradiation point is the highest, and there is an obvious temperature gradient at the laser irradiation boundary. With the increase of laser power, the temperature in the central region increases, and the heat affected zone becomes larger. It can be seen that the trend of change between the experimental results and the simulation results is basically the same. Within the temperature range of laser curing, the temperature fluctuation caused by heat release from cross-linked curing of prepreg is particularly tiny. Based on the principle of simplified calculations, the simulation model does not take this part of the energy into account, so that the simulation temperature is slightly lower than the experimental temperature. The temperature difference gradually decreases with increasing laser power. By comparing the experimental results and the simulation results of laser irradiation of CFRP materials, the accuracy of the theoretical model and the rationality of the experimental process and the simulation process are verified.

Figure 5 shows a longitudinal cross-section of the simulation model illustrating the temperature field distribution inside the prepreg during the laser curing process. As shown, as the laser power increases, the larger the heat affected region in the transverse and longitudinal directions.

Figure 6 shows the process of energy diffusion and temperature field formation inside the CFRP at a laser power of 5 W. After irradiating the surface of the sample with a near-infrared laser beam, the energy propagates in an elliptical plane on the upper surface due to the difference in the direction of heat conduction. On the other hand, as the curing depth increases, the unavoidable energy loss leads to the lower energy distribution in the inner layer than that of surface layer. Therefore, an ellipsoidal low-temperature three-dimensional temperature field is formed at the initial stage of curing. As time progresses, the laser energy accumulates in the prepreg and is continuously transmitted to form a high-temperature zone. This has a profound effect on the actual curing morphology of CFRP.

Morphological characteristics after in-situ curing

The macroscopic morphologies of cured CFRP with different layers using different laser power (see Fig. 7) were recorded by a HD industrial camera. Laser irradiation region and surrounding unirradiated region can be clearly demarcated. Cured profiles can be clearly found around the laser irradiation area. The cured morphology of CFRP is oval but not very regular. Cured area of the CFRP reduced gradually from the surface to inside.

After extracting the cured outline of each layer, three-dimensional cured profiles by near infrared laser and contour projection charts were drawn as Fig. 8. When the laser power was 3 W, the obvious cured region was 1–3 layers. When the laser power was 4 W, it changed to 1–5 layers. When the laser power was 5 W, it improved to 1–6 layers. It seems that the greater the laser power, the greater the depth and area of curing. The appearance morphology of each layer is approximately elliptical.

In view of this, the distribution of the simulated temperature field on the upper surface shows a regular elliptical shape. However, due to the heterogeneity of the CFRP microstructure, the laser energy transfer in CFRP is not stable, so the actual cured area shows different degrees of shrinkage, forming an irregular ellipse shape. The shrinkage of the CFRP cured area is more pronounced with increasing depth.

The characteristic can be described by an elliptic equation which is controlled by laser power and distance from the surface to the layer as follows:

where, w is the power of the laser and l is the distance from the surface to the layer. a and b are coefficients of equation related to the laser power and the distance from the surface.

The calculated results are shown in Fig. 9. Through the above formula, the curing range can be predicted by the given parameters (laser power, curing depth). As a result, the curing morphology can be designed by controlling these parameters.

Figure 10 illustrate the mechanism of laser curing CFRP. When the laser irradiates the surface of the CFRP composite, a strong thermal effect occurs on the surface of the material, resulting in a large amount of heat. Due to the high thermal conductivity of the carbon fiber, this heat is quickly transferred to the interior of the composite, forming multiple heat-affected zones.

The focal area is the most central area where the laser beam is focused. The area where the heat influence is strongest, and the temperature is the highest. In this area, the epoxy resin is oxidized and decomposed, leaving the carbon fiber bare. The curing zone is the heat affected zone adjacent to the focus zone, and has a higher temperature. In this region, the resin matrix begins to undergo a cross-linking reaction, causing the material to gradually cure. At the same time, the resin matrix is uniformly and tightly attached to the carbon fiber. The low temperature zone is the heat affected zone adjacent to the curing zone, and the temperature gradually decreases and gradually approaches the initial temperature of the substrate. In this region, there is almost no cross-linking of the resin matrix. So the resin is coated smoothly and evenly on top of the carbon fiber.

Performance characteristics after in-situ curing

The curing degree of resin matrix refers to the degree of curing crosslinking reaction of resin in composite materials, which is the core parameter to measure the crosslinking and curing behavior of resin during near-infrared laser curing.

When the laser power is 3 W (see Fig. 11a), 1–3 layers have significant curing effect, but the degree decreases with the layers. The curing degree at the first layer can reach 87%. It turned to 73% at the third layer. It is only 3% the fourth layer, which means almost no curing. When the laser power is 4 W (see Fig. 11b), 1–5 layers have comparatively higher curing degree. The first layer was up to 98%, which is close to a completed curing process. The fifth layer reached 56%, but the sixth layer is only 5% left. When the laser power is 5 W, the crosslinking curing reaction occurred at 1–6 layers as shown in Fig. 11c.

The curing degree and curing area decrease synergistically from the surface to the inside at the same laser power as shown in Fig. 12. In other words, the two characteristics of curing degree and curing area are positively correlated. When the laser irradiates the surface of the prepreg material, part of the energy will be reflected by the surface of the material. The residual energy of the laser obtained by each layer shows a decreasing trend from the surface to the center, which directly affects the temperature field distribution. The curing reaction is a chemical reaction, which is greatly affected by temperature, and is within the upper limit range of the curing temperature. The higher the temperature, the larger the curing area, and the higher the curing degree.

Therefore, the degree of cure of resin are consistent with the cured area of CFRP. This implies that, the degree of cure of CFRP can be estimated by the area of the cured ellipse as shown in Fig. 13. The prediction equation can be described as follows:

where, α is the curing degree of CFRP, s is the area of cured region which can be obtained from Eq. (12) and Eq. (18), and w is the power of laser.

Conclusions

In this paper, the temperature distribution characteristics, structure characteristics and mechanism of static in-situ near infrared laser curing of CFRP were studied. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) The characteristic law of temperature variation with time for static in-situ curing is analyzed. Under near infrared laser, the temperature of CFRP irradiation center changes with time in the form of power exponential function. On this basis, the curing temperature prediction equation and curing temperature control method based on power control and layer thickness parameters are proposed.

(2) The curing morphology of each layer of static in situ curing is analyzed. The results of the thermal model suggest that an elliptical shape and a layer-by-layer decreasing energy temperature field, as well as differences in shrinkage effects between different layers, give rise to an irregular ellipsoidal solidification morphology of the unidirectional CFRP, and its area of plane is related to laser power and curing depth. Therefore, the relationship equation between the curing morphology and the curing power and the curing depth was established, and the precise curing of CFRP could be achieved by controlling the laser power.

(3) The mechanism of near infrared laser curing of CFRP composites was revealed. The positive correlation between curing degree and curing area was obtained when the laser power was constant. The curing degree prediction equation based on curing morphology was established. The curing degree could be predicted simply by macroscopic curing morphology.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Wang, B. Y. et al. Enhanced impact properties of hybrid composites reinforced by carbon fiber and polyimide fiber. Polymers. 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13162599 (2021).

Jiao, J. K. et al. A review of research progress on machining carbon fiber-reinforced composites with lasers. Micromachines. 14, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14010024 (2023).

Saito, O., Liu, M. Y., Okabe, Y. & Soejima, H. Numerical analysis of Lamb waves propagating through impact damage in a skin-stringer structure composed of interlaminar-toughened CFRP. Compos. Struct. 277, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114639 (2021).

Xiao, Z., Mo, F. H., Zeng, D. & Yang, C. H. Experimental and numerical study of hat shaped CFRP structures under quasi-static axial crushing. Compos. Struct. 249, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112465 (2020).

Harrell, T. M., Thomsen, O. T. & Dulieu-Barton, J. M. Predicting the effect of lightning strike damage on the structural response of CFRP wind blade sparcap laminates. Compos. Struct. 308, 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.116707 (2023).

Kang, C. S., Shin, H. K., Chung, Y. S., Seo, M. K. & Choi, B. K. Manufacturing of Carbon Fibers/Polyphenylene sulfide composites via induction-heating molding: morphology, mechanical properties, and flammability. Polymers. 14, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14214587 (2022).

Ekuase, O. A., Anjum, N. & Eze, V. O. Okoli, O. I. A review on the out-of-autoclave process for composite manufacturing. J. Compos. Sci. 6, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs6060172 (2022).

Stadler, H., Kiss, P., Stadlbauer, W., Plank, B. & Burgstaller, C. Influence of consolidating process on the properties of composites from thermosetting carbon fiber reinforced tapes. Polym. Compos. 43, 4268–4279. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.26687 (2022).

Abliz, D. et al. Curing methods for advanced polymer composites - A review. Polym. Polym. Compos. 21, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/096739111302100602 (2013).

Coqueret, X., Krzeminski, M., Ponsaud, P. & Defoort, B. Recent advances in electron-beam curing of carbon fiber-reinforced composites. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 78, 557–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2009.03.042 (2009).

Tu, R. W., Liu, T. Q., Steinke, K., Nasser, J. & Sodano, H. A. Laser induced graphene-based out-of-autoclave curing of fiberglass reinforced polymer matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 226, 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109529 (2022).

Noe, C., Hakkarainen, M. & Sangermano, M. Cationic UV-curing of epoxidized biobased resins. Polymers. 13, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13010089 (2021).

Yang, H. H. et al. Achieving crack-free CuCrZr/AlSi7Mg interface by infrared-blue hybrid laser cladding with low power infrared laser. J. Alloy Compd. 931, 13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.167572 (2023).

Chen, H. L. et al. Recent advances of low-dimensional materials in mid- and far-infrared photonics. Appl. Mater. Today. 21, 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100800 (2020).

Wang, Z. H., Zhang, B., Liu, J., Song, Y. F. & Zhang, H. Recent developments in mid-infrared fiber lasers: Status and challenges. Opt. Laser Technol. 132, 20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2020.106497 (2020).

Bonardi, A. H. et al. High performance Near-Infrared (NIR) Photoinitiating systems operating under low light intensity and in the presence of oxygen. Macromolecules. 51, 1314–1324. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00051 (2018).

Zhu, J. Z., Zhang, Q., Yang, T. Q., Liu, Y. & Liu R. 3D printing of multi-scalable structures via high penetration near-infrared photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17251-z (2020).

Jardini, A. L., Maciel, R., Scarparo, M. A. F., Andrade, S. R. & Moura, L. F. M. Infrared laser stereolithography: prototype construction using special combination of compounds and laser parameters in localised curing process. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 21, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmpt.2004.004940 (2004).

Andrade, S. R., Jardini, A. L., Maciel, M. R. W. & Maciel, R. Numerical simulation of localized cure of thermosensitive resin during thermo stereolithography process (TSTL). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 102, 2777–2783. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.24456 (2006).

Mandic, V. N. et al. Blue laser for polymerization of bulk-fill composites: influence on polymerization kinetics. Nanomaterials. 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13020303 (2023).

Schmitz, C. & Strehmel, B. NIR LEDs and NIR lasers as feasible alternatives to replace oven processes for treatment of thermal-responsive coatings. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 16, 1527–1541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11998-019-00197-3 (2019).

Kumar, P. K., Raghavendra, N. V. & Sridhara, B. K. Effect of infrared cure parameters on the mechanical properties of polymer composite laminates. J. Compos. Mater. 46, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998311410490 (2012).

Wang, Y. W. et al. Infrared laser heating of GFRP bars and finite element temperature field simulation. J. Mater. Res. Technol-JMRT. 18, 3311–3318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.03.119 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. Microstructure and nanomechanical properties of Zr-based bulk metallic glass composites fabricated by laser rapid prototyping. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 765, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.138306 (2019).

Cheng, J. F., Lin, Z. X., Wu, D., Liu, C. L. & Cao, Z. Aramid textile with near-infrared laser-induced graphene for efficient adsorption materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 436, 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129150 (2022).

Groo, L. et al. Laser induced graphene in fiberglass-reinforced composites for strain and damage sensing. Compos. Sci. Technol. 199, 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108367 (2020).

Chern, B. C., Moon, T. J. & Howell, J. R. On-line processing of unidirectional fiber composites using radiative heating: I. Model. J. Compos. Mater. 36, 1905–1934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998302036016236 (2002).

Nakagawa, Y., Mori, K. I. & Yoshino, M. Laser-assisted 3D printing of carbon fibre reinforced plastic parts. J. Manuf. Process. 73, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.11.025 (2022).

Xie, Y. X., Yang, B. B., Lu, L. S., Wan, Z. P. & Liu, X. K. Shear strength of bonded joints of carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) laminates enhanced by a two-step laser surface treatment. Compos. Struct. 232, 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111559 (2020).

Xia, H. B. et al. Influence of laser welding power on steel/CFRP lap joint fracture behaviors. Compos. Struct. 285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115247 (2022).

Wang, W. H., Sui, L. & Jin, K. Design and heating simulation of continuous laser welding curing device for carbon fiber composite repair. J. Nanoelectron Optoelectron. 16, 1386–1394. https://doi.org/10.1166/jno.2021.3085 (2021).

Stokes-Griffin, C. M. & Compston, P. Optical characterisation and modelling for oblique near-infrared laser heating of carbon fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites. Opt. Lasers Eng. 72, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2015.03.016 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Qingdao Natural Science Foundation (23-2-1-246-zyyd-jch).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. and J.T., co-first authors of the study, conducted the primary study design and data analysis. K. J. and R. Y. provided assistance with data analysis. G.B. and L.Q. made important comments on the direction of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Li Wang and Jinpeng Tang conducted the main experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript writing, and both authors contributed equally to this work and are listed as co-first authors. Kai Jin and Richmond Polley Yankey proposed a computational model. Guido A. Berti and Luca Quagliato improved the calculation. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Tang, J., Jin, K. et al. Static in-situ curing characteristics of CFRP based on near infrared laser. Sci Rep 14, 23135 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73227-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73227-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experimental study on machinability and surface integrity of CFRP plate via magnetic field–assisted picosecond laser micromachining

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)