Abstract

Due to the fast-changing global climate, conventional agricultural systems have to deal with more unpredictable and harsh environmental conditions leading to compromise food production. The application of phytonanotechnology can ensure safer and more sustainable crop production, allowing the target-specific delivery of bioactive molecules with great and partially explored positive effects for agriculture, such as an increase in crop production and plant pathogen reduction. In this study, the effect of free pterostilbene (PTB) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with pterostilbene was investigated on Solanum lycopersicum L. metabolism. An untargeted NMR-based metabolomics approach was used to examine primary and secondary metabolism whereas a targeted HPLC–MS/MS-based approach was used to explore the impact on defense response subjected to anti-oxidant effect of PTB, such as free fatty acids, oxylipins and them impact on hormone biosynthesis, in particular salicylic and jasmonic acid. In tomato leaves after treatment with PTB and PLGA NPs loaded with PTB (NPs + PTB), both NPs + PTB and free PTB treatments increased GABA levels in tomato leaves. In addition, a decrease of quercetin-3-glucoside associated with the increase in caffeic acid was observed suggesting a shift in secondary metabolism towards the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids and other phenolic compounds. An increase of behenic acid (C22:0) and a remodulation of oxylipin metabolism deriving from the linoleic acid (i.e. 9-HpODE, 13-HpODE and 9-oxo-ODE) and linolenic acid (9-HOTrE and 9-oxoOTrE) after treatment with PLGA NPs and PLGA NPs + PTB were also found as a part of mechanisms of plant redox modulation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing the role of PLGA nanoparticles loaded with pterostilbene in modulating leaf metabolome and physiology in terms of secondary metabolites, fatty acids, oxylipins and hormones. In perspective, PLGA NPs loaded with PTB could be used to reshape the metabolic profile to allow plant to react more quickly to stresses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the current scenario of global climate change and rapid population increase, agriculture has been dealing with a wide range of challenges for food security and it demands efficient crop improvement methods to ensure food quality and quantity1. Current strategies in modern agriculture should consider efficacy, cost affordability, environmental safety, toxicity towards non-target organisms, and sustainability of the production system especially since some pathogen species are naturally resistant to certain types of drugs, and resistance can also develop over time because of the exposure to drugs used in a large amount. A solution could be provided by lowering the amount of the drug, thus delaying the appearance of resistance, as well as seeking novel natural products with antimicrobial activity, and using innovative approaches for delivering2,3. In this regard, nanotechnologies are recently emerging as revolutionary approaches to renew the resilient agricultural system and transform modern agriculture into precision agriculture2.

Nanoparticles (NPs) combined with bioactive compounds could offer a smart solution to improve crop growth and development as well as to control crop diseases limiting the use of conventional pesticides. In recent years, nanoparticles have also emerged as novel triggers for inducing the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds in plants4. Ag NP treatment increased artemisinin content by 3.9-fold in 20-day-old hairy root cultures of Artemisia annua L.5 Hydroponically grown Bacopa monnieri L. treated with copper-based NPs (Cu) improved antioxidant capacity and showed a hormetic increase in the content of saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids and phenols6. In any case, nanoparticles facilitate site-targeted delivery and controlled release of bioactive compounds, ensuring efficient utilization7,8.

Among nanomaterials, polymeric NPs are composed of natural or synthetic polymeric materials, some of which have desirable features such as biodegradability9. Among these, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs have been extensively studied, their biocompatibility has been proved9, and they have shown great potential for use in the development of nano-based delivery systems for plants10,11,12,13. PLGA has been approved by the FDA, WHO, and other regulating agencies. However, further studies be performed to guide the rational application of PLGA nanoparticles in agriculture and ensure sustainability. Resveratrol (3,5,4’-trihydroxystilbene) and its methoxylated derivative, pterostilbene (3,5-dimethoxy-4′-hydroxystilbene) (PTB), are synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway as antimicrobial phytoalexin in response to pathogen attacks. Whereas resveratrol has been identified in a wide number of food plants as peanut (Arachis hypogea), grape (Vitis vinifera), mulberry (Morus alba), pistachio (Pistachia vera) and tomato (S. lycopersicum), PTB has been found in a few plants and crops such as Vitis vinifera14, Pterocarpus marsupium15,16, Arachis hypogaea17 and Vaccinum species (berries)18 but not in S. lycopersicum. In this regard, PTB could represent a possible strategy to enhance the metabolic machinery of the plant and prepare the plant to better react to subsequent environmental stress. It has been demonstrated that PTB exhibits a strong antifungal activity against common crop fungal pathogens, such as Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Plasmopara viticola, Septoria nodorum, and Leptosphaeria maculans19,20 but its effect as natural compound on tomato plant metabolism is unknown. Further studies should be carried out to evaluate the impact and toxicity of PLGA NPs loaded with natural compounds on the metabolism of plants.

In the present work, tomato leaves were analyzed after treatment with PLGA NPs or PTB or PLGA NPs loaded with PTB (NPs + PTB) by an untargeted NMR-based metabolomics approach and a targeted HPLC–MS/MS approach to evaluate the free fatty acids, oxylipins, and plant hormones. In fact, free fatty acids have a role against abiotic (metals21 and temperature22) and biotic stress e.g. as signaling molecules23,24,25. Here, the oxylipins derived from the linoleic and linolenic acid were investigated, playing an important role as signaling molecules during plant defense processes in response to biotic or abiotic stress26. Since free fatty acids and the oxylipins are closely related to response towards stress an additional evaluation was carried out to define the alteration of the main hormones implicated in plant defense, that are the jasmonic acid and salicylic acid27.

The valuable insights that emerge showed metabolites linked both to primary and secondary metabolism suggesting an alteration of redox signaling promoting the plant defense capacity. With this study, we demonstrate the role of PLGA nanoparticles loaded with pterostilbene in modulating leaf metabolome and physiology in terms of secondary metabolites, free fatty acids, oxylipins and hormones. Future studies considering the exposition of plant to abiotic and biotic stresses including pathogens will be useful to determine the efficacy of PLGA NPs loaded with pterostilbene in improving the plant responses to stresses.

Results

Effect of PLGA NPs, PTB, and PLGA NPs loaded with PTB on the metabolome of tomato leaves evaluated by 1H-NMR

The analysis of the 600 MHz 1H-NMR spectra obtained from hydroalcoholic and chloroformic extracts of tomato leaves allowed to unequivocally identify 21 molecules. A total of 21 metabolites including organic acids, amino acids, organic compounds, sugars, fatty acids, phenylpropanoids, and other compounds were integrated. Comparing the spectra obtained from tomato leaves treated with water (Ctrl), PLGA NPs (NPs), PTB and PLGA NPs loaded with PTB (NPs + PTB), it was possible to observe qualitative differences. Examples of 1H-NMR spectra are reported in Supplementary Figures S1–S4, and the table of resonance assignment is shown in Supplementary Table S3. Quantitative analysis of the chemical composition of tomato leaves is reported in Supplementary Table S4. PLS-DA discriminant analyses were applied to highlight the most important metabolites discriminating the treatments with NPs, PTB, and NPs + PTB.

To evaluate the effect of PLGA NPs on the metabolism of tomato plants, the PLS-DA analysis was carried out by comparing plants treated with empty NPs and control plants (Ctrl) (Fig. 1). The PLS-DA score plot highlights the clear separation of the tomato plants treated with NPs (Fig. 1A) that showed higher levels of caffeic acid and lower levels of trigonelline, GABA and quercetin-3-glucoside compared to control plants (R2 = 0.999, Q2 = 0.77), as revealed by regression coefficients (Fig. 1B).

To investigate the effect of PTB treatment on the metabolism of tomato leaves, PLS-DA analysis was applied, and results are reported in Fig. 2. The score plot revealed a clear separation of tomato plants treated with PTB from untreated plants (Ctrl) (R2 = 0.998, Q2 = 0.93) (Fig. 2A). The levels of caffeic acid, valine, GABA, glucose and sucrose increased while alanine, arginine and choline levels decreased in plants treated with PTB compared to Ctrl plants (Fig. 2B).

In order to disentangle the metabolic changes due to the treatment with NPs loaded with PTB from the treatment with empty NPs, a PLS-DA was applied and a clear separation between the treatment groups was observed (R2 = 0.94, Q2 = 0.55) (Fig. 3A). The levels of GABA significantly increased in leaves treated with NPs + PTB compared to the NPs group. Conversely, the levels of glutamate and formiate significantly decreased in NPs + PTB group compared to the NPs group (Fig. 3B).

Finally, a PLS-DA was carried out to discriminate the effect of PTB from NPs loaded with PTB and results are reported in Fig. 4. The PLS-DA model represented by three factors and the following indices R2 = 0.99, Q2 = 0.80 (Fig. 4A), showed metabolic differences between the two treatments consisting in higher levels of choline, threonine, arginine and valine, and lower levels of sucrose and glucose in NPs + PTB group compared to the PTB group (Fig. 4B).

Effect of PLGA NPs, PTB, and NPs loaded with PTB on tomato leaf: phyto-oxylipin, fatty acid and hormone levels by HPLC–MS/MS

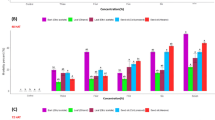

Exists a deeply link between the redox state, membrane fluidity and defense responses of plant cells. Free fatty acids assume a double role, they are constituents of cell wall and cell membranes, but during the pathogen infection they assume a role of signaling molecules. To better understand the effect of the treatments we evaluated palmitic (C16:0), palmitoleic (C16:1), stearic (C18:0), oleic (C18:1), linoleic (C18:2), linolenic (C18:3), behenic (C22:0), lignoceric (C24:0) and nervonic (C:24:1) acids, and we noted that the treatments proposed not alter the composition of free fatty acid except for C22:0 , that increase in tomato leaves treated with NPs, PTB and NPs + PTB compared to the Ctrl group (Fig. 5).

Free Fatty acid relative abundances in tomato plants treated with NPs, PTB, and NPs + PTB. Profile of all fatty acids analyzed. Ctrl: control, plants treated with distilled water; NPs: PLGA NPs; PTB: pterostilbene; NPs + PTB: PLGA NPs loaded with PTB. The data were expressed as the mean of three replicates and bars represent the standard error. Different letters represent significant differences Mann–Whitney U test was also run to determine significant differences for considered metabolites. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Oxylipins and hormones (salicylic acid and jasmonic acid) were also evaluated as markers linked to plant defense. Mass spectrometry analysis reveals a significant change in 9-HpODE, 13-HpODE and 9-oxo-ODE (18:2-derived), 9-HOTrE, 9-oxoOTrE (18:3-derived) and salicylic acid levels (Fig. 6). In particular, 9-HpODE and 13-HpODE significantly decreased in tomato leaves treated with PTB or NPs + PTB compared to the Ctrl group and NP treatment; 9-oxo-ODE, 9-HOTrE and 9-oxoOTrE significantly increased in plants treated with NPs compared to the Ctrl group and significantly decreased in NPs + PTB compared to NPs group. Salicylic acid levels significantly increased in plants treated with NPs compared to the Ctrl group, while in PTB and NPs + PTB decrease probably for the antioxidant effects .

Oxylipin and hormone abundances in tomato plants treated with NPs, PTB, and PTB NPs. Ctrl: control, plants treated with distilled water; NPs: PLGA NPs; PTB: pterostilbene; PTB NPs: PLGA NPs loaded with PTB; FW: fresh weight. The data were expressed as the mean of three replicates and bars represent the standard error. Different letters represent significant differences.

Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophyll (a and b) content in tomato leaves treated with NPs, PTB, and NPs + PTB

The content of chlorophylls and carotenoids was analyzed by spectrophotometric analysis and no significant differences were observed among the treatment groups with the respect of untreated controls (Figure S5 and S6).

Discussion

In this study, an omics approach was applied to investigate the metabolic changes in tomato leaves after treatment with PLGA NPs or PTB, a natural compound, or PLGA NPs loaded with PTB. The 1H-NMR- based metabolomic analysis allowed to highlight the metabolic effects due to PLGA NPs or PTB treatment used in its free form or loaded in NPs. A common biochemical pathway involving GABA metabolism was affected after treatment with PLGA NPs loaded with PTB or free PTB. In particular, an increase in GABA levels was observed after treatment with PLGA NPs loaded with PTB or free PTB. In addition, a decrease in glutamate levels, GABA precursor, was observed after treatment with PLGA NPs loaded with PTB. GABA is a ubiquitous four-carbon non proteinogenic amino acid that is greatly metabolized via the GABA shunt, a short pathway linked with several pathways such as the TCA cycle28,29 and glutamic acid decarboxylation. In plants, GABA plays important roles in carbon/nitrogen balance maintenance, regulation of cytosolic pH, protection against oxidative stress, energy production, cell elongation and leaf development regulation as well as germination, fruit ripening and senescence30,31. Similarly, to other plant molecules, such as calcium, jasmonic acid, salicylic or abscisic acid, GABA levels readily increase in response to environmental biotic and abiotic stresses and its concentrations range from micromolar (low) to millimolar (high) in different tissues, organs and cell compartments30,32,33.

Natural compounds such as resveratrol have been reported as effective priming agents34. Plant priming is a promising strategy consisting in an alteration of the plant’s physiological state intentionally promoted by natural products or synthetic chemicals to enhance the defense response in the case of subsequent harsher stresses35. When the plant reaches the “primed” state, the activated defense genes induce broad-spectrum defenses which change the metabolic profile and the accumulated defense compounds, among other processes, minimizing the negative effects on plant productivity36. Unlike the results reported by Pàramo et al.37 in which changes in the increasing or decreasing content of chlorophylls were observed under different treatments with metal nanoparticles, in the present study no significant differences were observed among the treatment groups with the respect of controls.

De Bona et al.38 demonstrated that stilbene-rich extracts obtained from grape canes induce defense responses by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and defense-related gene expression such as PR and Glutathione-S-transferase 1 (GST1) genes38. Kang et al.34 showed that resveratrol derivatives, as kobophenol A and hopeaphenol oligomers, can enhance priming events by promoting stronger local defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana. As reported by Duke39, severe plasma membrane damage in cucumber tissue caused by ROS and resulting in the accumulation of the protoporphyrin IX was restored through the exogenous application of resveratrol, pterostilbene, and α-tocopherol. Our results suggest that free PTB and PTB loaded in PLGA NPs could act as priming agents increasing GABA levels in tomato leaves, through the stimulation of GAD. Interestingly, tomato plants treated with free PLGA NPs showed lower levels of GABA compared to control plants confirming that the increase of GABA was due to PTB. As far as we know, there are no studies highlighting an increase in GABA levels in response to treatment with PTB in plants.

Amino acid metabolism is an important bridge between primary and secondary metabolites. Many amino acids are important precursors in the biosynthesis of alkaloids (e.g., arginine, lysine, ornithine, phenylalanine, proline, tryptophan, tyrosine), glucosinolates (e.g. methionine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan), and phenylpropanoids (e.g., phenylalanine and tyrosine)40,41. Among secondary metabolites, phenylpropanoids and flavonoids are crucial for their role in the preservation of the plant’s metabolic machinery and stress tolerance. In particular, phenylpropanoids are involved in the regulation of oxidative stress, free ion chelation, cell wall lignification, and plant defense42. In addition, secondary metabolites are also known to be involved in pest defense43 signal transduction in plant–microbe symbiosis44 and plant innate immunity45.

Most studies with NPs indicate their capability to modulate plant secondary metabolism, although the mechanism through which this process could occur is not understood. Accumulation of shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathway products was observed in cucumber and maize after foliar application of Cu(OH)246 in wheat exposed to Ag47 in pepper exposed to SiO2 or Fe2O348 and in A.thaliana exposed to CuO NPs49 The concentration of benzoic acid and gallic acid was increased, while the content of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives was reduced in C. sativus when exposed to CuO NPs50. In our study, the decrease of quercetin-3-glucoside associated with the increase in caffeic acid (3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid) observed after treatment with PLGA NPs and PTB suggests a shift in secondary metabolism towards the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids and other phenolic compounds. In this context, both PLGA NPs and PTB acted increasing the levels of a cinnamic acid primarily involved in the synthesis of lignin, in the regulation of cell expansion, turgor pressure, phototropism, water flux, and growth processes. Caffeic acid and derivatives are known to be involved in both plant biotic and abiotic stress tolerance51,52. In our study, the increase of caffeic acid was not associated with an increase in chlorogenic acid levels, being this latter an intermediate of its synthesis53. The PLS-DA model comparing PLGA NPs + PTB vs PTB (Fig. 4) highlighted a decrease of carbohydrates such as sucrose and glucose in aid of synthesis of amino acids as threonine, arginine, and valine. This effect was determined by PLGA NPs. Conversely, the treatment with PTB increased sucrose and glucose levels and decreased arginine, choline and alanine levels compared to the Ctrl group (Fig. 2). In other words, PLGA NPs promoted the carbohydrate catabolism and protein synthesis as opposed to PTB.

The modulation in plant hormone levels is directly correlated with the physiological performance of the plants. The intricate cross-talk between NP exposure and phytohormone signaling results in synergistic or antagonistic interactions that play crucial roles in the response of plants to stress and are just beginning to be understood. Fe-NPs have been reported to affect the endogenous concentration of salicylic acid in plants54.

In our study, an increase in salicylic acid levels was observed after treatment with PLGA NPs compared to control plants. Salicylic acid is a plant hormone synthesized from the shikimate pathway that plays a central regulatory role in plant immunity modulating disease resistance, stress tolerance, DNA damage/repair, fruit yield and seed germination as well as contributing to the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and the activation of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes55,56,57,58,59.

A strong increase of salicylic acid levels was observed after ZnONPs application in A. thaliana leaves60. The remarkable role of salicylic acid in stress amelioration after NPs exposure has been demonstrated in several studies61,62. Cai et al.61 demonstrated that the application of Fe3O4 NPs on N. benthamiana leaves increased salicylic acid biosynthesis and expression of salicylic acid-responsive PR genes (PR1 and PR2) leading to an improvement in plant resistance against TMV infection. On the other hand, the exposure of ZnONPs and co-treatment with exogenous salicylic acid in tobacco plants induced an increase of endogenous associated to the overexpression of salicylic acid-binding protein 2 (SABP2), which promoted the action of photosynthetic and antioxidative defense system63.

Interestingly, besides the salicylic acid levels, NPs increased also the levels of caffeic acid as compared to control plants, suggesting a defense response mediated by the nanoparticles.

Free fatty acids act as signaling molecules in several biological processes, including plant stress response64. Among the fatty acids analyzed, behenic acid (C22:0) significantly increased in the leaves of tomato plants treated with NPs, PTB and NPs + PTB compared to control plants. The C22:0 is produced via elongation system in the cytosol. Thus, it seems that NPs and PTB increased its synthesis. As C22:0 is present normally in a very low level in membrane complex lipids, it could be expected that its elevated level could be connected with increased synthesis of cuticle waxes65, the hydrophobic layers of leaf surfaces with an important role in SAR66,67. However, a detailed study of changes in lipid classes ‘structures of analyzed leaves had not been done during presenting research.

Marked alteration may be observed in oxylipin category, they are biologically active compounds acting as signaling molecules for defense and development which can be generated because of the action of free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Oxylipins are lipid mediators consisting in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), such as arachidonic acid (ARA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), α-linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA) and involved in reactions catalyzed by cyclooxygenase (COX), cytochrome P450 (CYP 450), lipoxygenase (LOX), as well as non-enzymatic oxidation pathways. Based on the position of the initial oxygenation, several enzymatic pathways can be described. Tomato has two 13-LOX genes and three 9-LOX genes. TomloxC, a 13-LOX gene, provides the substrate for jasmonate synthesis. TomloxD produces jasmonate in defense against herbivores68. In rice, the cross-talk between the 13-LOX and 9-LOX products was observed to lead to elevated JA levels that improved the responses against herbivores. In this study, products of 13-LOX and 9-LOX such as 9-HpODE and 13-HpODE, derived from linoleic acid (C18:2), significantly decreased in tomato leaves after treatment with PTB and NPs + PTB. Conversely, 9-oxo-ODE, 9-HOTrE and 9-oxoOTrE significantly increased in plants treated with NPs compared to the control group. 9-oxylipins were usually defined as “death oxylipins” since in A. thaliana they are upstream the event causing HR-related PCD and therefore closely related to salicylic acid elevation into challenged tissues69. NPs, even considering the result with behenic acid which clearly indicates a membrane-stress could trigger HR-related events. In this sense, the use of NPs charged with known antioxidants and inhibitors of LOXs (oxylipins significantly decreased in NPs + PTB compared to NPs group), suggesting the capacity of NPs and especially PTB70 loaded in NPs to differently modulate the oxylipin metabolism and consequently HR-related events. Considering the antioxidant proprieties of PTB, it could compensate for the stimulating effect of NPs, leading to a reduction in the redox potential of the plant and therefore lowering the oxidation of fatty acids to oxylipins. Several evidence support the use of exogenously applied antioxidants to improve both plant growth and their resilience to stress71. Concerning this, the proper dose of PTB charged in NP could modulate in a tailored way the response of plant to stresses.

Final remarks

In this study, the impact of PLGA NPs and PTB on the metabolism of S. lycopersicum L. was investigated by performing untargeted metabolomics by 1H-NMR and targeted analysis of lipidic compounds by HPLC–MS/MS. The obtained results demonstrated that both PLGA NPs and PTB affect the GABA, phenylpropanoid and lipidic metabolism of tomato plants. In this study we demonstrate the role of PLGA nanoparticles loaded with pterostilbene in redirecting leaf metabolome to boost the production of secondary metabolites, fatty acids, oxylipins and hormones. This leaf metabolic structure could prove useful to improve the plant defense response to future biotic or abiotic stress. Further studies will be needed to address the role of PLGA NPs loaded with PTB in environmental stress conditions. T hese data could be useful for interested researchers on developing alternative strategies to control crop plant diseases and constitute an important step forward in understanding the mechanisms of interaction between plant metabolism and NPs. In this context, we propose a possible use that should be further explored of PTB as a priming agent.

It should be emphasized that the impacts of whole NPs as well as of PTB on the yield and nutritional properties of crops are not exhaustively clarified. For this purpose, a coordinated research plan considering standardized experimental procedures, such as PTB concentrations, NPs application path and plant development stage, is necessary not only to guarantee the effect and to improve the crop production, but also to enhance plant tolerance towards environmental stresses and optimize the utilization of nutrients. Last, but not least, the future advances in phytonanotechnology will allow to make up for the vital gaps in regulatory and marketing policies driving a faster and safer development of nanotechnology for sustainable agriculture in the near future.

The 1H-NMR-based untargeted metabolomics and LC–MS-based lipidomics approach allowed to disentangle the contribution of metabolic variations due to PLGA NPs and PTB. These aspects are relevant to better understand the metabolic impact of the interaction between nanoparticles and bioactive compounds. The fact that the observed metabolic changes were not severe indicates that the treatment of tomato plants with PLGA NPs and PTB is safe but could also improve the content of phenols in S. lycopersicum L. in terms of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All solvents and standards used in this study were bought from VWR International (Milan, Italy) and Merck—Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany), unless specified otherwise. Pterostilbene was purchased from Chemodex (St. Gallen, Switzerland).

Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro release studies on PLGA NPs

Poly(D,L)-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), with a proportion 50:50 of lactide:glycolide and molecular weight of 50 kDa, was used for NPs preparation. 50 nm PLGA NPs, empty or loaded with PTB, were obtained by using the microfluidic reactor, as previously reported by Palocci et al.11 The reactor has a flow-focusing configuration described previously by Chronopoulou et al.12 PLGA NPs characterization and in vitro release studies of PTB from PLGA NPs have been conducted as described by De Angelis et al.8

Plant material

Tomato plants (S. lycopersicum cv ciliegino) with 3–4 true leaves were purchased from a commercial producer (Ortoflora Valter Finocchietti, Rome, Italy), and were cultivated in all-purpose soil (Compo Sana, Compo Italia Srl) in round pots (diameter 10 cm) under controlled conditions (photoperiod 16:8 light:dark at 24 °C during light hours and 20 °C during dark hours) in a phytotron before the experiments. The plants have not been subjected to any treatment by the producer. Each group (5 replicates) was treated with distilled water (control) or PLGA NPs (0.1 mg mL−1), or pterostilbene (PTB) (0.04 mg mL−1) or NPs loaded with PTB (0.04 mg mL−1, respectively), at the stage of 9 true leaves. The treatments were administered by spraying water or NPs suspension in water on the plants. The leaves were harvested 72 h after the treatment, immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until HPLC–MS/MS or 1H-NMR analysis. Otherwise, leaves were extracted immediately after harvesting for chlorophyll and carotenoid analysis by spectrophotometric methods.

Sample preparation for 1H-NMR analysis

Tomato leaves were sampled from nodes of the same age for each treatment. A total of 1.5 g of ground tomato leaves for each plant was extracted using a modified Bligh-Dyer protocol.72 In brief, five replicates for each treatment group were ground in a mortar with liquid nitrogen and added to a cold mixture composed of chloroform (3 mL), methanol (3 mL), and water (1.2 mL). The samples were stirred, stored at 4 °C overnight, and then centrifuged for 30 min at 4 °C with a rotation speed of 11,000 rpm. The upper hydrophilic and the lower organic phases were carefully separated and dried under a gentle nitrogen flow. A mixture of CD3OD/D2O in a ratio of 1:2 containing 3-(trimethylsilyl)-propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt (TSP, 2 mM) as an internal chemical shift and concentration standard was added to the hydrophilic phase The hydrophilic phase was then analyzed by 1H-NMR.

NMR experiments

NMR experiments were carried out at 298 K on a JNM-ECZ 600R spectrometer operating at the proton frequency of 600 MHz and equipped with a multinuclear z-gradient inverse probe head, and the monodimensional 1H and bidimensional 1H-1H TOCSY experiments were acquired according to Spinelli et al.73.

Free f atty acid, oxylipin and hormone extraction and HPLC–MS/MS analysis

All solvents used for the extraction and HPLC–MS/MS analysis were of HPLC/MS grade. Mass spectrometry analyses were carried out by a HPLC 1200 series rapid resolution coupled to a triple quadrupole MS (G6420 series triple quadrupole, QqQ; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with an electrospray ionization source (ESI). Chromatographic column and analysis software were purchased by Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The nitrogen flow was at 10 L/min, the nebulization pressure at 20 psi, the temperature was set at 350 °C, and the voltage at 4000 V.

Tomato leaves sampled from nodes at the same age were lyophilized and ground with liquid nitrogen. Simultaneous extraction method was used for free fatty acids, oxylipins and hormones following the protocol described in Beccaccioli et al.74. Briefly, 2 mL of extraction solution constituted by Isopropanol:Water:Ethyl Acetate (1:1:3 v/v) were added to 30 mg of powder leaf in presence of 1 µL of of butylated hydroxytoluene (0.0025% w/v) to avoid oxidation and 2 µL of 9-HODEd4 (Cayman Chemical) as internal reference standard (final concentration 2 µM calculated on the volume of final resuspension, 100 µL). The samples were vortexed (5 min), centrifuged (10 min, 4 °C, 10,000 rpm), and the supernatant taken. The extraction was repeated on the matrices with 1.2 mL of ethyl acetate. The collected supernatants were dried under nitrogen flux and the dried samples were resuspended with 100 μL of methanol.

The chromatographic separation of free fatty acids, oxylipins and hormones was performed with a Zorbax ECLIPSE XDB-C18 rapid resolution HT 4.6 × 50 mm 1.8 µm column (Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The extract was separated at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of A: water/acetonitrile (97:3 v/v containing 0.1% formic acid), and B: acetonitrile/isopropyl alcohol (90:10 v/v). The elution program was: 0–2 min 20% B, 2–4 min 35% B, 4–6 min 40% B, 6–7 min 42% B, 7–9 min 48% B, 9–15 min 65% B, 15–17 min 75% B, 17–18.50 min 85% B, 18.50–19.50 min 95% B, 19.50–24 min 95% B, 24–26 min 99% B, 26–30 min 99% B, 30–34 min 20% B. Sample was separated at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min (0–24 min), 1 mL/min (24–30 min), 0.6 mL/min (30–34 min). The column temperature was set at 60 °C. The injection volume was 10 µL. Free fatty acids were identified by single ion monitoring (SIM) approach, while o xylipins and hormones were identified by Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) approach . Detailed data on all the identified metabolites are shown in S1 and S2 tables.

Extraction and quantification of chlorophylls and carotenoids of tomato leaves

The content of chlorophylls and carotenoids was analyzed by spectrophotometric analysis75. A total of 50 mg of tomato leaves were sampled from nodes of the same age for each treatment. The samples were added to a 96% hydroalcoholic methanol solution (v/v), in a 1:50 ratio (w/v) and maintained at 4 °C under dark conditions for 72 h. The extract was then separated and analyzed using the Shimadzu UV-1280 spectrophotometer (Japan). The analysis for quantifying chlorophyll a (Chl a) and b (Chl b) was carried out at 666 nm and 653 nm, respectively. The total content of carotenoids (Cars) in leaves was determined at 470 nm. After obtaining the absorbances (abs) of the samples, chlorophylls and carotenoids were quantified with the following formulas and the quantity was expressed in µg gFW-1 (fresh weight):

Statistical analysis

Multivariate partial least square analysis (PLS-DA) was applied on the metabolomic data matrix with using the Unscrambler ver. 10.5 software (Camo Software AS, Oslo, Norway).

Univariate t-test and one-way ANOVA were carried out on the metabolomics and lipidomics data matrix, chlorophyll and carotenoids with SigmaPlot 14.0 software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed on each variable to assess data normality prior to one-way ANOVA. A Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to identify significant differences between categories (p < 0.05). Mann–Whitney U test was also run to determine significant differences for considered metabolites. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data supporting the results are included in the article. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Saritha, G. N. G., Anju, T. & Kumar, A. Nanotechnology-Big impact: How nanotechnology is changing the future of agriculture?. J. Agric. Food Res.10, 100457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100457 (2022).

Mittal, D., Kaur, G., Singh, P., Yadav, K. & Ali, S. A. Nanoparticle-based sustainable agriculture and food science: recent advances and future outlook. Front. Nanotechnol.2, 579954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2020.579954 (2020).

Simonetti, G. et al. Anti-Candida biofilm activity of pterostilbene or crude extract from non-fermented grape pomace entrapped in biopolymeric nanoparticles. Molecules24, 2070 (2019).

Rivero-Montejo, S. D. J., Vargas-Hernandez, M. & Torres-Pacheco, I. Nanoparticles as novel elicitors to improve bioactive compounds in plants. Agriculture11, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11020134 (2021).

Zhang, B., Zheng, L. P., Yi Li, W. & Wen Wang, J. Stimulation of artemisinin production in Artemisia annua hairy roots by Ag-SiO2 core-shell nanoparticles. Curr. Nanosci.9, 363–370 (2013).

Lala, S. Enhancement of secondary metabolites in Bacopa monnieri (L.) Pennell plants treated with copper-based nanoparticles in vivo. IET Nanobiotechnol.14, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-nbt.2019.0124 (2020).

Prasad, R., Bhattacharyya, A. & Nguyen, Q. D. Nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture: recent developments, challenges, and perspectives. Front. Microbiol.8, 1014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01014 (2017).

De Angelis, G. et al. A novel approach to control Botrytis cinerea fungal infections: uptake and biological activity of antifungals encapsulated in nanoparticle based vectors. Sci. Rep.12, 7989. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11533-w (2022).

Chronopoulou, L., Sparago, C. & Palocci, C. A modular microfluidic platform for the synthesis of biopolymeric nanoparticles entrapping organic actives. J. Nanopart. Res.16, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-014-2703-99 (2014).

Valletta, A. et al. Poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid nanoparticles uptake by Vitis vinifera and grapevine-pathogenic fungi. J. Nanopart. Res.16, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-014-2744-0 (2014).

Palocci, C. et al. Endocytic pathways involved in PLGA nanoparticle uptake by grapevine cells and role of cell wall and membrane in size selection. Plant Cell Rep.36, 1917–1928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-017-2206-0 (2017).

Chronopoulou, L. et al. Microfluidic synthesis of methyl jasmonate-loaded PLGA nanocarriers as a new strategy to improve natural defenses in Vitis vinifera. Sci. Rep.9, 18322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54852-1 (2019).

Orekhova, A. et al. Poly-(lactic-co-glycolic) Acid Nanoparticles Entrapping Pterostilbene for Targeting Aspergillus Section Nigri. Molecules.27, 5424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175424 (2022).

Kambiranda, D. M., Basha, S. M., Stringer, S. J., Obuya, J. O. & Snowden, J. J. Multi-year quantitative evaluation of stilbenoids levels among selected muscadine grape cultivars. Molecules.24, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24050981 (2019).

Manickam, M., Ramanathan, M., Jahromi, M. A., Chansouria, J. P. & Ray, A. B. Antihyperglycemic activity of phenolics from Pterocarpus marsupium. J. Nat. Prod.60, 609–610. https://doi.org/10.1021/np9607013 (1997).

Maurya, R. et al. Constituents of Pterocarpus marsupium: an ayurvedic crude drug. Phytochemistry.65, 915–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.01.021 (2004).

Sobolev, V. S. et al. Biological activity of peanut (Arachis hypogaea) phytoalexins and selected natural and synthetic Stilbenoids. J. Agric. Food Chem.59, 1673–1682. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf104742n (2011).

Rimando, A. M., Kalt, W., Magee, J. B., Dewey, J. & Ballington, J. R. Resveratrol, pterostilbene, and piceatannol in Vaccinium berries. J. Agric. Food Chem.52, 4713–4719. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf040095e (2004).

Adrian, M. & Jeandet, P. Effects of resveratrol on the ultrastructure of Botrytis cinerea conidia and biological significance in plant/pathogen interactions. Fitoterapia.83, 1345–1350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2012.04.004 (2012).

Koh, J. C., Barbulescu, D. M., Salisbury, P. A. & Slater, A. T. Pterostilbene is a potential candidate for control of blackleg in canola. PLoS One.11, e0156186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156186 (2016).

Verdoni, N., Mench, M., Cassagne, C. & Bessoule, J. J. Fatty acid composition of tomato leaves as biomarkers of metal-contaminated soils. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.20, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620200220 (2001).

Novitskaya, G. V., Suvorova, T. A. & Trunova, T. I. Lipid composition of tomato leaves as related to plant cold tolerance. Russ. J. Plant Physiol.47, 728–733 (2000).

Upchurch, R. G. Fatty acid unsaturation, mobilization, and regulation in the response of plants to stress. Biotechnol. Lett.30, 967–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-008-9639-z (2008).

Blée, E. Impact of phyto-oxylipins in plant defense. Trends Plant Sci.7, 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02290-2 (2002).

Beccaccioli, M. et al. Fungal and bacterial oxylipins are signals for intra-and inter-cellular communication within plant disease. Front. Plant Sci.13, 823233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.823233 (2022).

Deleu, M. et al. Linoleic and linolenic acid hydroperoxides interact differentially with biomimetic plant membranes in a lipid specific manner. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces175, 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.12.014 (2019).

Siebers, M. et al. Lipids in plant–microbe interactions. Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids.1861, 1379–1395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.02.021 (2016).

Shelp, B. J. & Zarei, A. Subcellular compartmentation of 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) metabolism in Arabidopsis: An update. Plant Signal Behav.12, e1322244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2017.1322244 (2017).

Gramazio, P., Takayama, M. & Ezura, H. Challenges and Prospects of New Plant Breeding Techniques for GABA Improvement in Crops: Tomato as an Example. Front. Plant Sci.11, 577980. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.577980 (2020).

Bouche, N. & Fromm, H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite?. Trends Plant Sci.9, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006 (2004).

Podlešáková, K., Ugena, L., Spíchal, L., Doležal, K. & De Diego, N. Phytohormones and polyamines regulate plant stress responses by altering GABA pathway. N. Biotechnol.48, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2018.07.003 (2019).

Kinnersley, A. M. & Turano, F. J. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and plant responses to stress. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci.19, 479–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352680091139277 (2000).

Ramesh, S. A., Tyerman, S. D., Gilliham, M. & Xu, B. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants. Cell Mol. Life Sci.74, 1577–1603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2415-7 (2017).

Kang, J. E., Yoo, N., Jeon, B. J., Kim, B. S. & Chung, E. H. Resveratrol oligomers, plant-produced natural products with anti-virulence and plant immune-priming roles. Front. Plant Sci.13, 885625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.885625 (2022).

Kerchev, P. et al. Molecular priming as an approach to induce tolerance against abiotic and oxidative stresses in crop plants. Biotechnol. Adv.40, 107503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107503 (2020).

Vijayakumari, K. & Puthur, J. T. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) priming enhances the osmotic stress tolerance in Piper nigrum Linn. plants subjected to PEG-induced stress. Plant Growth Regul.78, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-015-0074-6 (2016).

Páramo, L. et al. Impact of nanomaterials on chlorophyll content in plants. In Nanomaterial Interactions with Plant Cellular Mechanisms and Macromolecules and Agricultural Implications (eds Al-Khayri, J. M. et al.) (Springer, Cham, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20878-2_4.

De Bona, G. S. et al. Dual mode of action of grape cane extracts against Botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem.67, 5512–5520. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b07098 (2019).

Duke, S. O. Benefits of resveratrol and pterostilbene to crops and their potential nutraceutical value to mammals. Agriculture12, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12030368 (2022).

Barros, J. & Dixon, R. A. Plant phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia-lyases. Trends Plant Sci.25, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2019.09.011 (2020).

Jan, R., Asaf, S., Numan, M. & Lubna, K. M. Plant secondary metabolite biosynthesis and transcriptional regulation in response to biotic and abiotic stress conditions. Agronomy11, 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11050968 (2021).

Agati, G., Azzarello, E., Pollastri, S. & Tattini, M. Flavonoids as antioxidants in plants: location and functional significance. Plant Sci.196, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.07.014 (2012).

Stevenson, P. C. For antagonists and mutualists: the paradox of insect toxic secondary metabolites in nectar and pollen. Phytochem Rev.19, 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-019-09642-y (2020).

Adedeji, A. A. & Babalola, O. O. Secondary metabolites as plant defensive strategy: a large role for small molecules in the near root region. Planta252, 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-020-03468-1 (2020).

Piasecka, A., Jedrzejczak-Rey, N. & Bednarek, P. Secondary metabolites in plant innate immunity: conserved function of divergent chemicals. New Phytol.206, 948–964. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13325 (2015).

Zhao, L., Huang, Y. & Keller, A. A. Comparative metabolic response between cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and corn (Zea mays) to a Cu (OH)2 nanopesticide. J. Agric. Food Chem.66, 6628–6636. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01306 (2017).

Feng, L. et al. Synergetic toxicity of silver nanoparticle and glyphosate on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Total Environ.797, 149200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021a.149200 (2021).

Kalisz, A. et al. Nanoparticles of cerium, iron, and silicon oxides change the metabolism of phenols and flavonoids in butterhead lettuce and sweet pepper seedlings. Environ. Sci. Nano.8, 1945–1959. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1en00262g (2021).

Soria, N. G. C., Bisson, M. A., Atilla-Gokcumen, G. E. & Aga, D. S. High-resolution mass spectrometry-based metabolomics reveal the disruption of jasmonic pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana upon copper oxide nanoparticle exposure. Sci. Total Environ.693, 133443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.249 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. Antioxidant response of cucumber (Cucumis sativus) exposed to nano copper pesticide: Quantitative determination via LC-MS/MS. Food Chem.270, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.069 (2019).

Douglas, C. J. Phenylpropanoid metabolism and lignin biosynthesis: from weeds to trees. Trends Plant Sci.1, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/1360-1385(96)10019-4 (1996).

Riaz, U. et al. Prospective roles and mechanisms of caffeic acid in counter plant stress: A mini review. Pak. J. Agric. Res.32, 8. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjar/2019/32.1.8.19 (2019).

Kundu, A. & Vadassery, J. Chlorogenic acid-mediated chemical defence of plants against insect herbivores. Plant Biol. (Stuttg)21, 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12947 (2019).

Tripathi, D., Singh, M. & Pandey-Rai, S. Crosstalk of nanoparticles and phytohormones regulate plant growth and metabolism under abiotic and biotic stress. Plant Stress.6, 100107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2022.100107 (2022).

van Hulten, M., Pelser, M., Van Loon, L. C., Pieterse, C. M. & Ton, J. Costs and benefits of priming for defense in Arabidopsis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103, 5602–5607. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.051021310 (2006).

Wilson, D. C., Carella, P. & Cameron, R. K. Intercellular salicylic acid accumulation during compatible and incompatible Arabidopsis-Pseudomonas syringae interactions. Plant Signal Behav.9, e29362. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.29362 (2014).

Gully, K. et al. Biotic stress-induced priming and de-priming of transcriptional memory in Arabidopsis and apple. Epigenomes.3, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes3010003 (2019).

Koo, Y. M., Heo, A. Y. & Choi, H. W. Salicylic Acid as a Safe Plant Protector and Growth Regulator. Plant Pathol. J.36, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.RW.12.2019.0295 (2020).

Lefevere, H., Bauters, L. & Gheysen, G. Salicylic acid biosynthesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci.11, 338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00338 (2020).

Vankova, R. et al. ZnO nanoparticle effects on hormonal pools in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Total Environ.593–594, 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.160 (2017).

Cai, L. et al. Foliar exposure of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on Nicotiana benthamiana: Evidence for nanoparticles uptake, plant growth promoter and defense response elicitor against plant virus. J. Hazard Mater.393, 122415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122415 (2020).

El-Shetehy, M. et al. Silica nanoparticles enhance disease resistance in Arabidopsis plants. Nat. Nanotechnol.16, 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-020-00812-0 (2021).

Peng, D. et al. Exogenous application and endogenous elevation of salicylic acid levels by overexpressing a salicylic acid-binding protein 2 gene enhance nZnO tolerance of tobacco plants. Plant Soil450, 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04521-4 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Plant lipid remodeling in response to abiotic stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot.165, 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.06.005 (2019).

Kachroo, A. & Kachroo, P. Fatty Acid-derived signals in plant defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol.47, 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081820.PMID:19400642 (2009).

Yeats, T. H. & Rose, J. K. The formation and function of plant cuticles. Plant Physiol.163, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.222737 (2013).

Ding, P. & Ding, Y. Stories of salicylic acid: a plant defense hormone. Trends Plant Sci.25, 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2020.01.004 (2020).

Wasternack, C. & Feussner, I. The oxylipin pathways: biochemistry and function. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.69, 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.222737 (2018).

Sun, L. et al. Cotton cytochrome P450 CYP82D regulates systemic cell death by modulating the octadecanoid pathway. Nat. Commun.5, 5372. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6372 (2014).

Al-Khayri, J. M. et al. Stilbenes, a versatile class of natural metabolites for inflammation—an overview. Molecules28, 3786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093786 (2023).

Rodrigues de Queiroz, A. et al. The effects of exogenously applied antioxidants on plant growth and resilience. Phytochem. Rev.22, 407–447 (2023).

Tomassini, A. et al. (1)H NMR-based metabolomics reveals a pedoclimatic metabolic imprinting in ready-to-drink carrot juices. J. Agric. Food Chem.64, 5284–5291. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01555 (2016).

Spinelli, V. et al. Biostimulant effects of Chaetomium globosum and Minimedusa polyspora culture filtrates on Cichorium intybus plant: growth performance and metabolomic traits. Front. Plant Sci.13, 879076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.879076 (2022).

Beccaccioli, M. et al. The Effect of Fusarium verticillioides fumonisins on fatty acids, sphingolipids, and oxylipins in maize germlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 2435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052435 (2021).

Brasili, E. et al. Remediation of hexavalent chromium contaminated water through zero-valent iron nanoparticles and effects on tomato plant growth performance. Sci. Rep.10, 1920. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58639-7 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Sapienza Ateneo Grant 2019 n° RG11916B427D180B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB, MB, VP and LC performed the experiments; EB, CB and MB wrote the manuscript; MB, FS, EB, CB, VP analyzed the data, MR, AM, CP, GP critically evaluated the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Badiali, C., Beccaccioli, M., Sciubba, F. et al. Pterostilbene-loaded PLGA nanoparticles alter phenylpropanoid and oxylipin metabolism in Solanum lycopersicum L. leaves. Sci Rep 14, 21941 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73313-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73313-y