Abstract

Classifying malicious traffic, which can trace the lineage of attackers’ malicious families, is fundamental to safeguarding cybersecurity. However, the deep learning approaches currently employed require substantial volumes of data, conflicting with the challenges in acquiring and accurately labeling malicious traffic data. Additionally, edge network devices vulnerable to cyber-attacks often cannot meet the computational demands required to deploy deep learning models. The rapid mutation of malicious activities further underscores the need for models with strong generalization capabilities to adapt to evolving threats. This paper introduces an innovative few-shot malicious traffic classification method that is precise, lightweight, and exhibits enhanced generalization. By refining traditional transfer learning, the source model is segmented into public and private feature extractors for stepwise transfer, enhancing parameter alignment with specific target tasks. Neuron importance is then sorted based on the task of each feature extractor, enabling precise pruning to create an optimal lightweight model. An adversarial network guiding principle is adopted for retraining the public feature extractor parameters, thus strengthening the model’s generalization power. This method achieves an accuracy of over 97% on few-shot datasets with no more than 15 samples per class, has fewer than 50 K model parameters, and exhibits superior generalization compared to baseline methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing frequency of cyber attacks, national-level threats often come into public view, causing significant negative impacts on public life and social order1. As the initial step in the network malicious resource detection task, malicious traffic classification has garnered widespread attention2.

To evade tracking and detection, malicious actors employ several techniques. First, they often use encryption to obscure their activities, making it difficult for traditional inspection methods3,4,5,6 to identify threats. Second, malicious actors design their traffic to minimize detection, resulting in smaller, less noticeable traffic spikes. Activities such as Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) might only involve sporadic data transfers or connection attempts, making it hard to accumulate significant traffic data. Low peak and infrequent traffic data often lead to few-shot problems7. Third, attackers frequently change their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to avoid creating a predictable pattern. These characteristics of malicious traffic present significant challenges in establishing a reliable traffic classification model.

In recent years, deep learning has become the mainstream method for traffic classification8,9,10,11. However, deep learning is data-driven, and the few-shot size of malicious traffic data is insufficient to train a powerful model, resulting in poor generalization capability and high error rates. Additionally, deep learning model has a substantial structure. For instance, the classic traffic classification model DeepPacket12 contains over 30 million parameters and demands up to 2.1 billion calculations. Some edge network devices, such as routers, possess limited computational resources, making it challenging to meet the computational demands of deep learning13. Moreover, the significant computational load posed by large models relative to the target tasks creates conflicts with the need for real-time classification, especially for delay sensitive traffic. Against this backdrop, this paper focuses on three aspects: accuracy, lightweight design, and generalization of classification models for few-shot malicious traffic classification tasks, and conducts research and improvement based on current technology.

Firstly, since the transferability of deep learning models has been confirmed14,15, deep transfer learning has been recognized as a favorable framework for few-shot classification tasks16,17,18. During conventional transfer processes, shallow network parameters are often directly copied from the source to the target model19,20, introducing biases due to differences between datasets. Additionally, there is a marked need to enhance the methods for discerning similarities within traffic data, implying that shallow network parameters should be effectively retrained rather than duplicated. Due to the challenge of fine-tuning the entire model with limited samples, this paper introduces the concept of stepwise transfer. It contemplates the stepwise transfer of shallow and deep networks, categorized as public and private feature extractors. By incorporating a subset of the source dataset, this method aids in retraining shallow network parameters, tailoring them to extract features more accurately aligned with the target task. This approach improved adaptation of models to their intended few-shot tasks.

Secondly, in the context of few-shot scenarios, this paper focuses on lightweighting transfer models. The effectiveness of transfer learning largely hinges on the inclusion of well-suited sparse subnetworks for the target task21, leading to an abundance of redundant neurons for the target task. Given this, the paper explores the use of pruning methods to trim redundant model structures for model lightweighting, as the precise model structure plays a significant role in the classification accuracy the model can provide22,23. The success of pruning relies on accurately identifying redundant neurons, necessitating that the neuron weights of the trained model are positively correlated with the target classification task. Consequently, this paper addresses the specific problem of model lightweighting under few-shot conditions. By combining the proposed step-by-step transfer method, we perform model pruning on both the shallow and deep networks for different feature extraction tasks, making it more targeted compared to traditional integrated pruning.

In the study of lightweight models for few-shot malicious traffic, the issue of model generalization cannot be ignored. Under few-shot conditions, the limited training data prevents the model from accounting for feature diversity. This often leads to a high penalty for errors, increasing the risk of overfitting and thus resulting in suboptimal model performance during task transfer. Additionally, the purpose of a lightweight model is to remove model structures irrelevant to the current task without affecting accuracy. This process may lead to the elimination of neurons that extract basic features, rendering the post-lightweighting model structure specific only to the current task24. These dual objectives introduce challenges in solving the generalization issue of lightweight models in few-shot tasks. To address this, the paper proposes incorporating an adversarial concept during the training phase to extract public features. This involves considering the generality of features extracted by the shallow network of the transfer model, alongside their utility for the target classification task, as a joint training objective. This approach aims to uncover invariant representations within the sample data, ultimately enhancing the model’s generalization capability.

In summary, the design of lightweight model for few-shot malicious traffic classification still faces the following challenges:

Challenge1. Model accuracy: Owing to the inherent differences between source and target datasets, transfer models are susceptible to negative transfer. Furthermore, the limited capacity for fine-tuning with a few-shot size leads to suboptimal accuracy in the transferred models.

Challenge2. Pruning effectiveness: Biases in the shallow network parameters of transfer models concerning the target classification task prevent accurate ranking of neurons’ contributions, thus diminishing the effectiveness of model pruning.

Challenge3. Model generalization: Due to the extremely high sparsity of the lightweight model, and the use of few-shot dataset fine-tuning makes the model further over-fitting, resulting in poor generalization of the model.

In response to the above challenges, we propose a few-shot malicious traffic classification lightweight model design method STPN. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

We propose a novel stepwise transfer method, wherein the source model is retrained separately as a public and a private feature extractor to mitigate biases in parameter fine-tuning that arise from differences between transfer datasets.

-

The method employs fine-grained pruning of the transfer model’s convolutional layers based on the feature extraction objectives of the network layers, resulting in precise model parameters reduction without significant performance loss.

-

An adversarial learning idea is introduced into the training of the public feature extractor to discover invariant features between transfer datasets, enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities. To the best of our knowledge, the first investigation into the generalization issue of lightweight models in few-shot scenarios.

-

The proposed method consistently achieves over 97% classification accuracy on various few-shot datasets, outperforming current mainstream few-shot traffic classification methodologies. Notably, it reduces model parameters by over 85% while limiting accuracy loss to within 1%, thus demonstrating superior generalization compared to other lightweight techniques.

Related work

According to the research objectives of this paper, we sort out the related work of few-shot malicious traffic classification method based on deep transfer learning and model lightweight method.

Few-shot traffic classification based on deep transfer learning

Since the transferability of deep learning models has been confirmed, researchers have explored various methods to apply large models to few-shot tasks. For example, He et al.25 proposed a deep feature-based autoencoder network for detecting malicious traffic in a small number of scenarios. Initially, attempts were made to simultaneously train the source model on both the source and target datasets. However, the imbalance resulting from the discrepancy in dataset sizes led to poor performance of the transfer model in targeted classification tasks26. Further, researchers duplicated the parameters of the source model, fine-tuning it solely with the target dataset, a practice that often resulted in difficulties converging when samples are scarce27,28.

Currently, researchers freeze the shallow network parameters of the source model, allowing only the fine-tuning of the remaining parameters with the few-shot dataset, which has yielded positive results. Guan et al.29 applied deep transfer learning to address dataset scarcity in the classification of 5G IoT system traffic, achieving near-full dataset accuracy levels with only 10% of the labeled data. Guarino et al.30 transferred knowledge trained in resource-rich source domains to target domains with sparse resource availability. Despite limited resource access, their method maintained classification performance and increased classification speed. Idriss et al.31 applied transfer learning to update deep learning-based Intrusion Detection Systems (DL-IDS) solutions. Furthermore, Eva et al.32 proposed an efficient intrusion detection framework based on transfer learning, knowledge transfer, and model refinement, considering the potential for freezing shallow network parameters, which achieved high accuracy and a low false positive rate. However, previous methods have paid limited attention to the impact of the correlation between transfer datasets on model performance. Ma et al.33 introduces an adversarial domain adaptation approach combining a dual domain pairing strategy for IoT intrusion detection under few-shot samples. The method minimizes the distribution difference between source and target domains while employing adversarial learning to enhance detection performance in the target domain.

Model lightweight

As deep learning continues to evolve, the substantial architecture of neural networks is increasingly at odds with the limited resources of edge devices, leading to a demand for lightweight models capable of few-shot classification. In recent years, researchers have proposed a myriad of techniques for model lightweighting, including low-rank factorization34, knowledge distillation35,36, quantization37, and pruning38,39. Model pruning involves the selection and removal of redundant neurons based on their contribution to the classification task, resulting in a new model structure that aligns with our aim of optimizing non-beneficial sparse subnetworks in transfer models.

Various domains have witnessed trials in model pruning, with Liu et al.40 pioneering a lightweighting approach known as “network slimming” that achieved channel-level sparsity, reducing the size of the VGGNet model by approximately 20-fold and computational operations by five-fold. Focusing on the issues of weight reduction rate and convergence time in the pruning process, Zhang et al.41 proposed a systematic weight pruning framework for DNNs using alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM), which reduced the total computation by five times compared to the baseline. Subsequently, Xu et al.42 employed filter pruning as the main tool for reconfiguration, and used two optimization methods, ‘algorithm-oriented’ and ‘resource-aware,’ to effectively reconfigure the DNN model according to the resource constraints of different mobile devices. Niu et al.43 evaluated the compatibility of their proposed pattern-based pruning scheme with compiler code generation and developed multiple novel compiler optimizations for compressed DNN execution. Liao et al.44 merged model compression with transfer learning to create a streamlined custom model. Zhao et al.45 utilized filter pruning for model compression, crafting lightweight trainable models for large-scale image recognition tasks. Going further, Poyatos et al.46 addressed the oversight of fully connected layers in model pruning by replacing the final dense layers with sparsely populated ones optimized by genetic algorithms, and applying global pruning to lighten the overall model. However, most current pruning methods lack fine-grained pruning of the network layers in transfer models tailoring to the specific goals of the transfer.

STPN method

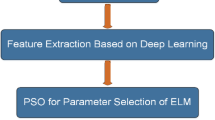

This paper introduces a lightweight model design methodology tailored for few-shot malicious traffic classification tasks. Initially, we designed and trained a source model for transfer learning based on a fully convolutional neural network architecture. Subsequently, we transferred the shallow network layers from the source model and added a classification layer to configure it as a public feature extractor. This extractor was fine-tuned using a combination of partial source dataset and target dataset data to facilitate the extraction of public features. Furthermore, the fine-tuned shallow network was integrated with the deeper network, and the parameters of the shallow layers were frozen to ensure that the deep network functioned exclusively as a private feature extractor for precise fine-tuning. Upon completing the transfer and fine-tuning of both feature extractors, the importance of neurons was evaluated for model pruning. The target dataset was then used to reform the new model structure, resulting in the final lightweight model optimized for few-shot malicious traffic classification. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of our method.

Problem definition

This section introduces symbols and annotations to define the optimization aims of the method. Assuming \({W_s}\) is a source model, \(_{s}\) represents that the model has been optimized for the source domain. In this study, \({D_s}\) and \({D_t}\) are utilised to represent the source and target data. \(\mathcal{L}\) is a loss function used to optimize the network. In the source model training stage, the optimization objectives might be defined as follows:

In the context of stepwise transfer learning, this study proposes using a subset of source data in conjunction with the entire target dataset to collaboratively guide a public feature extractor \({E_c}\). Concurrently, only the target dataset is employed to fine-tune a private feature extractor \({E_p}\). The optimization objective for the transfer model is defined as follows:

In the pruning phase, it is assumed that \({W^f}\) is the transfer model and \(f\) is the number of all neurons in the transfer model. The purpose of this study is to discover the most lightweight structure \({W^{f*}}\) according to a specified pruning ratio \(q\), while ensuring that the model’s loss in classification accuracy on the target task remains below 1%. This can be expressed as follows:

Source model architecture

In this work, we developed a classification model based on a fully convolutional neural network (FCNN) to serve as the source model for transfer learning. The selection of an FCNN is justified by its capability to evaluate and optimize neurons in all layers except the final classification layer, significantly reducing the complexity of the network structure.

Considering the distinctive features of network traffic data, a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) serves as the core architecture of the proposed model. This architecture is capable of capturing byte-level dependencies within traffic packets and discerning distinctive patterns across various categories. The model is empirically constructed with 10 layers of one-dimensional CNN and 7 pooling layers, allocating 200 and 100 neurons to the convolutional layers at the shallow and deep ends, respectively. The convolutional layers have a stride of 1, while the pooling layers have a stride of 2. Batch Normalization (BN) layers are appended to each convolutional layer, except for the last layer, which acts as the classifier. Beyond their traditional role in preventing overfitting and expediting model convergence, the scaling factors in BN layers are instrumental during the pruning stage for evaluating the importance of neurons. The ReLU function is adopted as the activation function. The model’s detailed structure and parameters are presented in Fig. 2.

In contrast to traditional classification models, the proposed model uses convolutional layers to replace fully connected layers as the classifier. The neurons in these layers are connected to only a localized region of the input data, sharing parameters within the convolutional stacks. This trait better suits the model pruning requirements that follow. Neurons in both fully connected and convolutional layers perform dot product computations and are functionally analogous. Hence, it is practical to replace fully connected layers with convolutional ones. By setting the input channel number of the final convolutional layer to match the number of classification categories and performing several convolutions and pooling operations, the model’s last layer outputs a high-dimensional feature map of the input sample. Vector values from this feature map are used as the prediction scores for classification, and through forward propagation, model training is completed. The dataset was divided into two equal parts: 50% for the training set and 50% for the test set. After five-fold cross-validation on the training set, hyperparameters were adjusted using a grid search based on the optimal average precision.

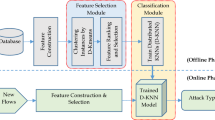

Model stepwise transfer

In this study, the source model is restructured into two distinct components for transfer: a public feature extractor and a private feature extractor. Each extractor engages a different transfer method and employs a unique loss function to recalibrate parameters, enhancing the network’s feature representation capabilities for the designated task. After their respective transfer processes, these extractors are fused into a unified model that incorporates both a common representation resembling that found across two datasets and a private representation tailored for the target few-shot dataset. Such a stepwise transfer approach ensures that the classifier, fine-tuned on the common representation, generalizes better across domains as it is not influenced by domain-specific representational traits. Concurrently, the few-shot dataset is solely responsible for the fine-tuning of the private representation, reducing its training burden and yielding a classifier with improved performance.

Public feature extractor transfer

In this research, the public feature extractor is designed to identify an invariant representation between the source and target datasets while retaining its classification capabilities for the target dataset. By mining the public features across datasets, the model ensures that the extracted features are beneficial when applied to other tasks. To achieve these objectives, the paper introduces an adversarial approach that facilitates this process.

Initially, this paper transfers the parameters of the shallow network layers from the source model. The selection principle for shallow network parameters is that the features extracted in this layer should be common to both the source and target datasets. A common feature is defined as one that does not allow the input data to be identified as either from the source dataset or the target dataset based on this feature. Therefore, it is possible to iteratively perform binary classification tasks on different network layers for samples from both datasets and identify the network layer with higher loss as the shallow network. The rationale behind the selection of these particular shallow layers is thoroughly discussed in Section B of the appendix and will not be reiterated here. Subsequently, a classifier is integrated with the shallow network to form a public feature extractor. This classifier is responsible for two classification tasks: Firstly, classifying whether a sample belongs to the source dataset or target dataset is considered as task1 in the network. If the shallow network extracts public features, the classification loss of task1 will be significant. Therefore, a gradient reversal layer (GRL) is introduced. The gradient reversal layer, denoted by function1, is formally expressed as the reversal of gradients:

By incorporating the gradient reversal layer, during the training of the public feature extractor, as the backpropagation proceeds, the original loss of the classifier increases. This increase in loss results in a decrease in the overall loss, thereby promoting the extraction of shared features.

However, the characteristic that determines the increase in the loss function of the domain classification task is the public feature, which easily guides the network to extract meaningless features. Therefore, in this paper, we construct classification task2, by training a public feature extractor for the source and target domains to perform multi-classification tasks on the samples, in order to counteract the meaningless behavior of the public feature extractor during training. The ultimate training objective of the public feature extractor is to minimize the following loss:

\(\partial\) is a parameter that controls the interaction of loss terms. The adjustment process of parameters is discussed in depth in Appendix A, and is not expanded here.

Under the action of two loss terms, the loss function outputs the common loss of the current parameters of the network for domain classification and sample category classification, and performs back propagation to direct the network to adjust the parameters to extract valuable public features. The training process of the public feature extractor is shown in Fig. 3.

Private feature extractor transfer

The objective of the private feature extractor is to search for the private features of the target few-shot dataset. Therefore, we freeze the retrained shallow network parameters to directly output the public features. We add the shallow network to the remaining layers of the source model as the private feature extractor and train it using the target dataset. The private feature extractor encourages the extraction of features that can distinguish different sample categories in the target task, minimizing the discrepancy between each target dataset sample \({y_i}\) and its predicted value \({p_i}\) Therefore, the loss function is defined as follows:

Transfer model pruning

Model pruning evaluates the contribution of neurons in a well-trained network through specific evaluation methods. This requires that the training of neuron weights during model training be effective. Traditional pruning methods directly rank and prune all neuron parameters of the transfer model uniformly. This approach may lead to the removal of redundant neurons that are beneficial for the source dataset classification task but not for the transferred target task, as the transfer network only fine-tunes the deep network using the target dataset for parameter adjustment. To address this problem, based on the step-by-step transfer approach, this paper divides the model into a public feature extractor and a private feature extractor for pruning and reshaping, respectively. This ensures that the pruned redundant parameters are beneficial for the few-shot classification task. Since parameter retraining has already been performed based on the different tasks of the two extractors during step-by-step transfer, the pruning work only requires determining the weight ranking and sequentially pruning the neurons.

The source model proposed in this work is comprised solely of convolutional layers, so it only needs to consider the redundancy of neurons in the convolutional layers. This reduces the operational complexity of the pruning stage and allows for a global pruning method based on the BN layer scaling factor. As the data normalization procedure before the activation layer in the neural network, the BN layer performs the following conversion:

\({z_{in}}\) and \({z_{out}}\) are the input and output of the BN layer, \(B\) is the current training batch, \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are the mean and standard deviation values of the input activation, \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\) are the trainable affine transformation parameters (ratio and shift), which provides the possibility of returning the normalized activation linear transformation to any ratio. In this study, the parameter in the BN layer was used as an index to evaluate neurons. During the pruning process, the values of all BN layers are first statistically sorted. Next, the values in the BN layers are traversed, and a mask is applied to each layer (assigning 1 to weights greater than the threshold and 0 to those less than the threshold). The non-zero indices from this mask are then retained, and the corresponding neuron weights are preserved. Finally, a new model structure is generated according to the mask, and the pruned model is loaded. The weights of the pruned model are assigned, and the model is reshaped. The threshold is defined as a percentile of the value. As the model is pruned iteratively, different thresholds are set for public feature extractors and private feature extractors to ensure that the accuracy of their respective classification tasks is maintained within a 1% margin. The pruning algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 1.

Based on the aforesaid pruning procedure, the model is pruned step by step. Firstly, for the public feature extractor, the parameters of the transferring network BN layer are collected and pruned according to the threshold, to search for the ideal network structure that can extract effective public features. For the private feature extractor, the pruning is performed according to the same approach. After the pruning is completed, it is integrated with the optimal structure sought by the public feature extractor to get a new network, and the target dataset is utilised to reshape the new network structure.

Experiments

In this section, we first present experimental settings. Then, we conduct experiments on multiple datasets and baselines and analyze the results. We also analyze the pruning effectiveness of STPN to demonstrate the lightweighting results of the model. Finally, we conducted task transfer experiments on STPN to evaluate the generalizability of the model.

Experimental settings

Dataset

In this paper, three public datasets, namely ISCX VPN-nonVPN, USTC-TFC, MCFP, and a Self-Made dataset, are used as experimental datasets. Among them, the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset is used to train the source model, while the USTC-TFC, MCFP, and Self-Made Dataset are used to evaluate the STPN method as target classification datasets. To align with the focus of this study, we selected subsets from the three datasets to serve as few-shot datasets and performed data balancing and preprocessing on them. The detailed information of the four datasets is shown in Table 1, including data types, highest visible protocol, number of sample classes, average quantity of packages per class and dataset size. Due to space limitations, the text only shows the information of the data set. The detailed information of each type of sample is shown in Appendix C.

ISCX VPN-nonVPN47: The captured data consists of normal traffic packets generated by various applications, as well as encrypted data packets captured through virtual private network (VPN) sessions and Tor software traffic.

USTC-TFC48: The traffic packets included in this study are generated by nine types of malware collected by CTU researchers from real network environments between 2011 and 2015.

MCFP: The data includes network files, logs, DNS requests, and other artifacts generated by malicious programs, all in the pcap format.

Self-made dataset: To replicate the performance of the model in a real-world scenario, we simulated the attack behavior of nine types of Trojans. The primary type is remote access Trojans, which are remotely controlled through different protocols to steal sensitive information or execute malicious commands. The Trojan program is implanted into a pre-deployed victim computer (virtual machine) and triggers an attack behavior through a remote control tool (such as a C&C server) to simulate a real attack scenario. During this process, the Wireshark packet capture tool is used to collect the traffic data during the attack and save it in PCAP format, forming our proprietary dataset. The details of this custom dataset are shown in Table 2.

Data preprocessing

The preprocessing process is implemented to filter and unify the format of traffic data, including filtering redundancies, truncating data, removing bad samples, and normalizing. Firstly, the useless Ethernet header information is removed for traffic classification. Secondly, due to the different header lengths of the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP), there are format differences in the input. To address this, zeros are injected at the end of the UDP segment header to make its length equal to that of the TCP header. Additionally, the IP address information is masked. The dataset is captured in a real simulation environment, and meaningless packets that do not contain valid payloads are discarded. Finally, to standardize the sample size for the input of the neural network, vectors with sample sizes exceeding 1500 are truncated, and byte vectors smaller than 1500 are padded with zeros. In the normalization stage, each element of the vector is divided by 255 to normalize the byte vector.

Implementation details and baselines

The experiments were performed using the following hardware and software platforms: All models with PyTorch 0.4.1 in each experiment 10 times independently to take average on a single NVIDIA GeForce GTX1650.

In the experiment, the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset was used to train the source model. The USTC-TFC, MCFP, and custom datasets were randomly sampled, with 15 samples selected from each type to simulate few-shot datasets. Among these, 70% were used as training sets, 20% as test sets, and 10% as validation sets for the supervised training and pruning of the transfer model. We conducted multi-dataset experiments, baseline method comparison experiments, and model robustness experiments. The hyperparameters used during the model training process are shown in Table 3.

In the method comparison experiment, we selected Deeppacket12, CNN-LSTM49, Idriss et al.31, and Eva et al.32 as the baselines for the accuracy test of few-shot traffic classification. Deeppacket and CNN-LSTM are classic models in the field of traffic classification. Idriss et al. and Eva et al. are newly proposed methods addressing the issue of few-shot classification using transfer learning. For the lightweight test, we used the methods proposed by Liu et al.40 and Liao et al.44 as baselines for comparison. Liu et al.‘s method is a classical model pruning technique, while Liao et al.‘s method is a lightweight few-shot traffic classification model based on pruning.

Multiple dataset experiment

Accurate classification of target tasks is a critical objective in the design of classification models. Therefore, this subsection presents tests conducted on models trained with the STPN method using three distinct datasets. The procedure involved training a source model with the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, which consists of regular traffic data. The STPN method was then applied for stepwise transfer learning and pruning. Throughout this process, training sets from three targeted few-shot datasets were used for fine-tuning, resulting in lightweight classification models adapted for classification tasks. The classification models were tested individually using their respective partitioned test sets. In order to provide an intuitive representation of the method’s multi-classification performance on various datasets, the classification results are presented in a heatmap as illustrated in Fig. 4.

For different types of malicious traffic samples, this method uses an end-to-end one-dimensional convolutional neural network as the main body of the classification model. This method can adapt to the encryption characteristics of malicious traffic samples. The malicious samples in the three sample data sets are mostly remote control trojans. The traffic transmitted by such trojans shows the characteristics of low peak and low frequency, and it is not easy to capture the complete traffic. Therefore, we randomly select 15 samples to form a few-shot for model training, and design a step-by-step transfer and pruning strategy to make the model parameters and target tasks better for it and extract more effective features. At the same time, the common feature extraction enhancement strategy in this paper also makes the model transfer more inclusive of the differences between the source data set and the target data set. Finally, on three few-shot datasets, the model shows an average classification accuracy of 97.74%, 99.22%, and 98.00%.

Comparison experiments

Comparison with few-shot classification methods

In this section, we compare the STPN method with the classical traffic classification methods, including Deeppacket, CNN-LSTM, and the methods proposed by Idriss et al. and Eva et al., in the field of few-shot traffic classification on three few-shot datasets. In the comparison, we follow the model structure and parameters used by the authors in the original paper. For the methods of Idriss et al. and Eva et al., we adhere to their prescribed model transfer and fine-tuning procedures. Table 4 summarizes the performance and model efficiency of these methods in different classification tasks.

Table 4 shows that the STPN method outperforms other methods in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score indicators, all of which exceed 97 points. Traditional traffic classification methods have poor accuracy in few-shot problems due to the mismatch between the number of parameters and the amount of data. Additionally, the huge model has obvious disadvantages in the number of model parameters and the Flops index. Compared with the other two mainstream few-shot classification methods, the STPN method retrains the parameters rather than simply freezing them, ensuring that the shallow network parameters are more consistent with the target task. Also, in the model pruning stage, fine-grained hierarchical pruning is used to remove redundant neurons and structurally make the model more effectively adapt to the target task. Therefore, the STPN method achieves the highest accuracy, and its model complexity is significantly reduced. Specifically, it uses only 0.3% of the parameters required by the Idris method, 1.2% of the parameters required by the Eva method, and FLOPS is reduced by about 40%.

Comparison with the lightweight methods

This section conducts tests on the classification performance of STPN compared with the current prevalent lightweight methods proposed by Liu et al. and Liao et al. across three few-shot datasets. This evaluation also considers the quantity of parameters and the number of computational operations required by the models when achieving optimal classification accuracy.

To ensure an equitable comparison, all three methods undergo transfer learning and pruning on the source model established in this paper. For the method by Liu et al., this study follows their original guideline of retaining only the architecture of the pruned model, discarding the weights, and randomly initializing new weights for subsequent training. Regarding Liao et al.‘s method, it aligns with their prescribed order of pruning prior to transfer, applying a superior global pruning strategy based on the average neuron weight identified by the authors, with fine-tuning of the model weights employed during transfer. For these three methods, iterative pruning was ceased when the maximum accuracy was maintained, ensuring that the pruning process did not compromise model performance. The results of this comparative analysis are detailed in Table 5.

In terms of the number of parameters and computational operations, the STPN method does not exhibit a significant advantage over the other two methods. However, it demonstrates a markedly superior classification accuracy. This is attributed to the fine-grained parameter matching conducted during transfer learning and pruning in this work, which mitigates issues related to negative transfer and over-pruning, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the lightweight model. Furthermore, this paper proposes the use of fully convolutional neural networks as the source model, inherently making the model more lightweight than traditional architectures and allowing for more extensive pruning. As a result, the final lightweight model obtained in this study has a parameter count of only approximately 50 K.

Comparative experiment based on ROC curve

To comprehensively compare the STPN method with other baseline approaches, we have plotted the ROC curves for the classification of six baseline methods on the Self-Made few-shot dataset in this section and calculated their AUC values. In the ROC curves, the x-axis represents the False Positive Rate (FPR), while the y-axis represents the True Positive Rate (TPR). The closer the curves are to the upper left corner, the better the classification performance. The AUC value, which stands for the area under the ROC curve, offers an intuitive measure of the classifier’s performance across different samples. As depicted in Fig. 5, our method achieves a higher true positive rate across various data classes. The average AUC values for the seven methods are as follows: STPN (0.99), Deeppacket (0.93), CNN-LSTM (0.92), Idriss (0.92), Eva (0.96), Liu (0.96), and Liao (0.96).

Comparison of time consumption and memory usage

For classification models, time consumption is also an important comparison indicator. Therefore, in this section, we refer to the method of He et al. and record the time consumption of STPN and six baseline methods during the model training and testing stages. We also calculate the memory resource consumption required for the classification model. For Deeppacket, CNN-LSTM, Idriss, and Eva, the original authors did not perform lightweight processing, so these methods do not include pruning duration. However, as shown in Table 6, the STPN method consumes less time than the other four methods in the long run. This is because when the source model is designed, STPN adopts a fully convolutional structure and uses a convolutional layer as the classification layer. The convolutional layer parameters are shared, sparsely connected, and the computational complexity is low, saving a significant amount of computation time. Additionally, when pruning the fully convolutional structure, only parameter sorting and model reconstruction are needed, which simplifies the computation and reduces the time required.

In comparison with other pruning methods, for the sake of fairness, STPN and the two baseline methods perform pruning operations under the transfer model of this paper. The results show that because STPN performs step-by-step pruning of both the shallow and deep networks, the time consumption is higher than that of the two baseline methods. However, the pruning operation itself does not involve complex calculations, so the difference in time consumption is not significant. From the memory usage of the final model, it can be seen that the pruned model only requires about 50 MiB of computing resources, which is much lower than traditional classification models. This paper investigates the computing resources available on current market edge computing devices. Generally, low-end edge devices (embedded microcontrollers, edge routers, etc.) have about hundreds of KB to dozens of MiB of storage resources. Middle-end edge devices (mobile robots, home smart devices, etc.) have about dozens of MiB to hundreds of MiB, and high-end edge devices (smartphones, edge servers, etc.) have several GB to dozens of GB. Therefore, based on the lightweight operation in this paper, the model can meet the deployment constraints of most edge devices while maintaining accuracy.

STPN lightweight experiment

Traditional methods of pruning shallow layers in transfer models often involve sorting neurons based on their weights initialized from the source model. This criterion may inadvertently lead to the removal of beneficial neurons if the copied weights do not positively correlate with the target classification task. To address this issue, our study implements a phased approach to transfer and pruning. By retraining shallow network parameters, we enhance their relevance to the target classification task, thereby improving the accuracy of pruning and minimizing the chances of removing beneficial neurons.

To evaluate whether the STPN can accurately remove neurons that play a minor role in extracting public features from shallow networks, this section presents a comparative analysis involving lightweight model structures resulting from both traditional methods and the STPN method after pruning. This analysis involves generating and vertically concatenating feature maps from the shallow networks at pruning rates of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8, to visually assess the effectiveness of pruning within the shallow network. The findings of this analysis are presented in Fig. 6.

In the domain of network traffic, packet header information often contains public feature information of the samples. Therefore, neurons that yield feature maps with sparse packet header information are considered to minimally contribute to the extraction of public features. As shown in Fig. 6, traditional methods do not markedly remove neurons with sparse packet header information as the pruning rate increases. This is evident in the feature maps, where the sparsity of packet header information is indicated by the red circles. In contrast, the STPN method retains neurons containing rich information as the pruning rate increases.

70

STPN generalization analysis

This section tests the generalizability of the STPN method using the task transfer probe experiment proposed by Aghajanyan et al.51. Specifically, the lightweight models STPN, Liu, and Liao are initially trained on a self-made dataset to set the model parameters. After training, the full set of parameters from each model is duplicated, with only the classification layer adjusted to adapt to the unknown classification tasks of three datasets: ISCX VPN-nonVPN, USTC-TFC, and MCFP. The goal is to explore the models’ transfer classification performance without further training on these new tasks. Performance testing of the lightweight models derived from the three methods is conducted at pruning rates of 40%, 60%, and 80%. As commonly understood, a higher pruning rate suggests a greater degree of fit to the initial target. By setting different pruning rates, this study aims to investigate whether the STPN method maintains its performance superiority on unknown tasks when subject to high levels of sparsity.

The heatmap presented in Fig. 7 shows the task transfer capability of different methods applied to three unknown datasets at certain pruning rates, where each cell represents the average accuracy for multi-classification tasks. The STPN method differentiates between the transfer of public and private features, and the application of adversarial concepts in the public feature extractor ensures that the extracted public features are foundational elements of traffic data. Consequently, as pruning rates increase, the STPN method retains these essential features, which benefits the classification of unknown tasks. At higher pruning rates of 60% and 80%, the STPN method notably exhibits superior generalization capabilities.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a lightweight model design method for few-shot malicious traffic classification. The method improves upon traditional transfer learning by dividing the model transfer process into stepwise shallow network transfer and deep network transfer, resulting in a model that is more aligned with the target few-shot task. During the training of the public feature extractor, an adversarial concept is introduced to leverage a portion of the source dataset for extracting more generalized data features, thereby enhancing the model’s generalizability. Additionally, based on the stepwise transfer, the model undergoes fine-grained pruning of both feature extractors to achieve structural compatibility with the target few-shot task. Using a fully convolutional neural network as the source model further enhances the lightweight nature of the model. Experimental results indicate that the proposed method yields a classification model that is more accurate, lighter, and exhibits greater generalizability compared to existing few-shot traffic classification methods and lightweight approaches. This work could offer a new perspective for research on lightweight models in few-shot malicious traffic classification.

Future work can focus on two key aspects. Firstly, the method needs to be adjusted to keep up with changes in the network environment, open new category spaces, and expand the classification ability of new samples through the class incremental method to address updated iterations of real applications. Secondly, the method needs to reuse the dataset for fine-tuning during transfer and pruning. The reuse of data increases the model’s sensitivity to training data, thereby increasing the difference in predictive confidence between training and non-training data. This will pose specific data privacy risks to the pruned neural network. Future studies can focus on reducing retraining times and improving the privacy protection of training data to enhance model security.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khan, M. & Ghafoorr, L. Adversarial machine learning in the context of network security: challenges and solutions. J. Comput. Intell. Robot. 4, 51–63 (2024).

Haque, M. A. & Palit, R. A review on deep neural network for computer network traffic classification. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 2205, 10830. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.10830 (2022).

Dainotti, A., Pescape, A. & Claffy, K. C. Issues and future directions in traffic classification. IEEE Netw. 26, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.2012.6135854 (2012).

Khalife, J., Hajjar, A. & Diaz-Verdejo, J. A multilevel taxonomy and requirements for an optimal traffic-classification model. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 24, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/nem.1855 (2014).

Lashkari, A. H., Draper-Gil, G. & Mamun, M. S. I. Characterization of encrypted and VPN traffic using time-related features. In The International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP) 407–414 (2016).

Yamansavascilar, B., Guvensan, M. A. & Yavuz, A. G. Application identification via network traffic classification. In International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC) 843–848 (2017).

Wang, Y., Yao, Q. & Kwok, J. T. Generalizing from a few examples: A survey on few-shot learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 53, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/3386252 (2020).

Schreiber, L. V., Atkinson, A. J. G. & Guimarães, L. Above-ground biomass wheat estimation: Deep learning with UAV-based RGB images. Appl. Artif. Intell. 36, 2055392 (2022).

Zheng, H., Liu, J. & Ren, X. Dim target detection method based on deep learning in complex traffic environment. J. Grid Comput. 20, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-177944/v1 (2022).

Samant, R. M., Bachute, M. & Gite, S. Framework for deep learning-based language models using multi-task learning in natural language understanding: A systematic literature review and future directions. IEEE Access 10, 17078–17097 (2022).

Le, N. Q. K., Ho, Q. T. & Nguyen, V. N. BERT-promoter: An improved sequence-based predictor of DNA promoter using BERT pre-trained model and SHAP feature selection. COMPUT. BIOL. CHEM. 99, 107732 (2022).

Lotfollahi, M., Jafari, S. M. & Shirali, H. Z. R. Deep packet: A novel approach for encrypted traffic classification using deep learning. Soft Comput. 24, 1999–2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-019-04030-2 (2020).

Aceto, G., Ciuonzo, D. & Montieri, A. Mobile encrypted traffic classification using deep learning: Experimental evaluation, lessons learned, and challenges. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. 16, 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2019.2899085 (2019).

Yosinski, J., Clune, J. & Bengio, Y. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. (NIPS) 27 (2014).

Neyshabur, B., Sedghi, H. & Zhang, C. What is being transferred in transfer learning? Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 512–523. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2008.11687 (2020).

Chen, B. J. & Chang, R. Y. Few-shot transfer learning for device-free fingerprinting indoor localization. In International Conference on Communications (ICC) 4631–4636 (2022).

Dhillon, H. & Haque, A. Towards network traffic monitoring using deep transfer learning. In IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom) 1089–1096 (2020) (2020).

Xu, C., Shen, J. & Du, X. A method of few-shot network intrusion detection based on meta-learning framework. IEEE Trans. Inform. Forensics Secur. (TIFS) 3540–3552. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2020.2991876 (2020).

Jiang, J., Shu, Y. & Wang, J. Transferability in deep learning: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2201.05867. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.05867 (2022).

Zhang, W., Deng, L. & Zhang, L. A. Survey on negative transfer. IEEE-CAA J. Autom. 10, 305–329. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2022.106004 (2023).

Frankle, J. & Carbin, M. The lottery ticket hypothesis: finding sparse, trainable neural networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1803.03635 (2019).

Zhao, R. et al. A novel intrusion detection method based on lightweight neural network for internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. (JIOT) 9960–9972. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3119055 (2021).

Alazzam, H., Sharieh, A. & Sabri, K. A lightweight intelligent network intrusion detection system using OCSVM and Pigeon inspired optimizer. Appl. Intell. (AI) 52, 3527–3544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-021-02621-x (2022).

Xu, R., Luo, F. & Wang, C. From dense to sparse: Contrastive pruning for better pre-trained language model compression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 11547–11555 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v36i10.21408

He, M. et al. Deep-feature-based autoencoder network for few-shot malicious traffic detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. (SCN) 6659022https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6659022 (2021).

Rezaei, S. & Liu, X. How to achieve high classification accuracy with just a few labels: A semi-supervised approach using sampled packets. arXiv preprint arXiv. 1812, 09761. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1812.09761

Xiao, Y., Sun, H. & Zhuang, Z. Common knowledge based transfer learning for traffic classification. In Conference on Local Computer Networks 311–314 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCN.2018.8638070

Bousmalis, K., Trigeorgis, G. & Silberman, N. Domain separation networks. NIPS 29 (2016).

Guan, J., Cai, J. & Bai, H. Deep transfer learning-based network traffic classification for scarce dataset in 5G IoT systems. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 12 3351–3365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-021-01415-4 (2021).

Guarino, I., Wang, C. & Finamore, A. Many or few samples? Comparing transfer, contrastive and meta-learning in encrypted traffic classification. In Network Traffic Measurement and Analysis Conference (TMA) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.23919/TMA58422.2023.10198965 (2023).

Idrissi, I., Azizi, M. & Moussaoui, O. Accelerating the update of a DL-based IDS for IoT using deep transfer learning. J. Indones J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 23, 1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.11591/IJEECS.V23.I2.PP1059-1067 (2021).

Rodríguez, E., Valls, P. & Otero, B. Transfer-learning-based intrusion detection framework in IoT networks. Sensors 22, 5621 (2022).

Ma, W., Liu, R., Li, K., Yan, S. & Guo, J. An adversarial domain adaptation approach combining dual domain pairing strategy for IoT intrusion detection under few-shot samples. Inform. Sci. (IS) 719–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2023.02.031 (2023).

Zhou, A., Yao, A. & Guo, Y. Incremental network quantization: towards lossless CNNs with low-precision weights. arXiv preprint arXiv. 1702, 03044, (2017). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1702.03044

Urban, G., Geras, K. J. & Kahou, S. E. Do deep convolutional nets really need to be deep (or even convolutional)? arXiv Preprint arXiv. 160 (05691). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1603.05691 (2016).

Zhang, L., Tan, Z. & Song, J. SCAN: A scalable neural networks framework towards compact and efficient models. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. (NIPS). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.03951 (2019).

Jung, S., Son, C. & Lee, S. Learning to quantize deep networks by optimizing quantization intervals with task loss. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 4350–4359 (2019).

Liu, B., Cai, Y., Guo, Y. & TransTailor pruning the pre-trained model for improved transfer learning. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 8627–8634 (2021).

Li, G., Ma, X. & Wang, X. Optimizing deep neural networks on intelligent edge accelerators via flexible-rate filter pruning. Syst. Archit. 124, 102431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sysarc.2022.102431 (2022).

Liu, Z., Li, J. & Shen, Z. Learning efficient convolutional networks through network slimming. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2755–2763 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.298

Zhang, T. et al. A systematic DNN weight pruning framework using alternating direction method of multipliers. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) 184–199 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01237-3_12

Xu, Z., Yu, F., Liu, C., Chen, X. & Reform static and dynamic resource-aware dnn reconfiguration framework for mobile device. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 1–6. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3316781.3324696

Niu, W. et al. PatDNN: Achieving real-time DNN execution on mobile devices with pattern-based weight pruning. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems 907–922. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3373376.3378534

Liao, C. Y., Liu, P. & Wu, J. Convolution filter pruning for transfer learning on small dataset. Int. Comput. Symp. (ICS) 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICS51289.2020.00025 (2020).

Zhao, K., Chen, Y. & Zhao, M. Enabling Deep Learning on Edge devices through Filter Pruning and Knowledge transfer. arXiv e-prints 2201, 10947. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.10947 (2022).

Poyatos, J., Molina, D. & Martinez, A. D. EvoPruneDeepTL: An evolutionary pruning model for transfer learning based deep neural networks. Neural Netw. 158, 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2022.10.011 (2023).

Draper-Gil, G., Lashkari, A. H., Mamun, M. S. I. & Ghorbani, A. A. Characterization of encrypted and vpn traffic using time-related. In Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on information systems security and privacy (ICISSP) 407–414 (2020). https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/vpn.html/

Wang, W. et al. Malware traffic classification using convolutional neural network for representation learning. In 2017 International conference on information networking (ICOIN) 712–717 (2017).

Zhuang, Z. et al. Encrypted traffic classification with a convolutional long short-term memory neural network. In IEEE 20th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications; IEEE 16th International Conference on Smart City; IEEE 4th International Conference on Data Science and Systems (HPCC/SmartCity/DSS) (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/HPCC/SmartCity/DSS.2018.00074 (2018).

He, M., Huang, Y., Wang, X. L., Wei, P. & Wang, X. J. A lightweight and efficient IoT intrusion detection method based on feature grouping. IEEE Internet Things J. (JIOT). 11, 2935–2949. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3294259 (2023).

Aghajanyan, A., Shrivastava, A. & Gupta, A. Better fine-tuning by reducing representational collapse. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2021).

Sun, G., Liang, L. & Chen, T. Network traffic classification based on transfer learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 69, 920–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2018.03.005 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.N. and M.H. conceived the experiments. J.J. and W.J. conducted the experiments. H.Z. and Z.W. analyzed the results. L.Q. drafted the manuscript. R.N., M.H. and J.J. edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Huang, M., Zhao, J. et al. A lightweight model design approach for few-shot malicious traffic classification. Sci Rep 14, 24710 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73342-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73342-7