Abstract

The plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)→mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor (mBDNF) pathway plays a pivotal role in the conversion of probrain-BDNF (ProBDNF) to mBDNF, but its clinical relevance in patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) remains unknown. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to examine the relevant protein levels of components of the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway in plasma samples from three groups of subjects, and statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and one-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Our findings revealed significant alterations induced by alcohol. (1) AUD was associated with significant decreases in tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), mBDNF, and tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB); significant increases in PAI-1, ProBDNF, and P75 neurotrophin receptor (P75NTR); and inhibited conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF. (2) Following abstinence, the levels of tPA, mBDNF, and TrkB in the AUD group significantly increased, whereas the levels of PAI-1, ProBDNF, and P75NTR significantly decreased, promoting the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF. These clinical outcomes collectively suggest that AUD inhibits the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF and that abstinence reverses this process. The PAI-1→mBDNF cleavage pathway is hypothesized to be associated with AUD and abstinence treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents a significant global challenge with serious implications for both economies and public health in numerous countries1. Neuroimaging of patients with AUD has shown damage to the hippocampus, amygdala, cerebellum, nucleus ambiguous, corpus callosum, and brainstem2, and alcohol has been shown to adversely affect neurocognitive function3. In basic experiments, chronic alcohol use in rats causes prefrontal cortex neuronal cell death, leading to cognitive impairment4. However, the precise mechanisms through which alcohol inflicts harm to the body remain elusive, and the mechanisms underlying the effects of abstinence treatment for AUD in clinical practice are still poorly understood.

In clinical practice, abstinence remains the primary approach for addressing AUD. However, the precise mechanism underlying alcohol-induced damage to the body is not clear, and there are currently no specific drugs that target the bodily harm caused by AUD. mBDNF plays a key role in AUD, and significantly reduced levels of mBDNF have been observed in patients with this disorder5,6. Elevating the mBDNF level has demonstrated significant potential in reversing the neurotoxic effects induced by alcohol use7,8,9,10,11. This is attributed to the capacity of mBDNF to bind to the TrkB receptor, thereby fostering the survival, growth, and differentiation of neuronal cells12. Inhibiting this process leads to the accumulation of ProBDNF, which, upon binding to P75NTR, can promote neuronal atrophy and apoptosis13. Previous studies have shown that PAI-1 and tPA are key proteases involved in the cleavage of ProBDNF to mBDNF, where tPA mainly plays a role in hydrolytic cleavage14, and the activity of tPA is tightly regulated by its natural inhibitor PAI-115. Studies in patients with Alzheimer’s disease have shown that the upregulation of PAI-1 inhibits the production of fibrinolytically regulated mBDNF16,17. Clinical studies in depressed patients have shown that the tPA fibrinogen system influences and plays an important role in the cleavage of ProBDNF to mBDNF14. Therefore, this study proposed the pathway PAI-1→mBDNF, and its mechanism is shown in Fig. 1.

PAI-1→mBDNF partial mechanism. PAI-1 is a natural inhibitor of tPA that tightly regulates tPA. tPA is a key protease involved in the cleavage of ProBDNF. proBDNF binds to P75NTR and causes neural atrophy and apoptosis. mBDNF binds to the TrkB receptor and promotes neuronal survival, growth, and differentiation.

With respect to patients with AUD, however, there is no literature that clearly indicates whether alcohol affects mBDNF production through the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway. Excessive alcohol intake can lead to an increase in PAI-118, and there is an overall increase in fibrinolytic activity following abstinence, which is driven mainly by a decrease in the PAI-1 level19. Moreover, clinical studies have indicated that the serum mBDNF level is significantly reduced in patients with AUD20. During abstinence, the serum mBDNF level is significantly greater than that in nonabstinence conditions21. Similar patterns have also been reported in animal experiments. Chronic alcohol intake decreases BDNF protein levels22. High chronic alcohol intake significantly reduces mBDNF expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus23. The mBDNF protein level increases following long-term alcohol abstinence24. Based on these findings both in humans and in animals, it is reasonable to hypothesize that alcohol similarly influences mBDNF production through the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway, but there are no studies supporting this.

In summary, it is important to further investigate the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway in depth in clinical patients with AUD. The current study explored this issue for the first time. First, the trends of PAI-1→mBDNF pathway-related proteins under different levels of alcohol stimulation were assessed. Second, abstinence treatment was performed on patients with AUD in the clinic to observe protein variations. PAI-1→mBDNF pathway-related proteins were dynamically observed and analyzed in the our two-dimensional study, aiming to explore the possible role of the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway in the pathology associated with AUD.

Methodology

Participants

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Jinhua City, China. All the experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). A total of 45 male subjects were recruited from October 2021 to October 2023, and the subjects were enrolled in the study after signing an informed consent form. These subjects were categorized into three groups: healthy controls (HCs), alcohol nondependent (AN) patients, and patients with AUD.

The HC group, comprising individuals with no history of alcohol intake, reported an average daily alcohol intake of 0 g (pure ethanol) over the previous three months. The AN group was characterized by individuals with a history of alcohol intake exceeding 35 g (pure ethanol) per day in the past three months but not meeting the criteria for AUD as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). The AUD group consisted of subjects who met the diagnostic criteria for AUD according to the DSM-5 and reported an average daily alcohol intake exceeding 50 g (pure ethanol) over the past three months.

The exclusion criteria included concurrent abuse or dependence on other nonnicotine drugs, including sedatives; recent use of sedatives within the past month; presence of severe physical illness; presence of other mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression; and severe cognitive impairment, making it difficult to understand the study content. For patients diagnosed with AUD, the oral administration of oxazepam was initiated at doses ranging from 30 to 120 mg/d, tailored to the severity of abstinence symptoms. Additionally, symptomatic supportive treatment was provided to alleviate abstinence symptoms effectively. The flowchart of this experiment is shown below in Figs. 2 and 3.

In this study, the subjects were divided into three groups according to their alcohol intake: HC healthy controls, AN alcohol nondependent, AUD alcohol use disorder. Baseline assays and statistical analyses of plasma levels of PAI-1, tPA, mBDNF, ProBDNF, TrkB, and P75NTR were performed in all three groups.

Blood sampling

During the baseline period and at the 2nd and 4th weeks of AUD abstinence, fasting venous blood samples of 5 ml were obtained from subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups at 7 a.m. These samples were then carefully transferred into blood collection tubes containing 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and gently mixed to prevent blood clotting. The blood samples were subsequently transferred into centrifuge tubes containing protease inhibitor peptides, gently mixed once more, and centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting plasma was collected and stored in an 80 °C freezer for subsequent analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to quantify the levels of tPA, PAI-1, mBDNF, ProBDNF, TrkB, and P75NTR in plasma samples. The test kits used were from ELK Biotechnology, with the following item numbers: tPA (ELK8621), PAI-1 (ELK1250), mBDNF (ELK1394), ProBDNF (ELK8417), TrkB (ELK9411), and P75NTR (ELK9458). Measurements were performed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experiment was performed in duplicate to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted via SPSS 22.0, and the experimental results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (means ± SDs). Intergroup comparisons of demographic data were analyzed via the chi-square test, while multigroup comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons via the least significant difference method. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze data from the AUD group at each time point. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 reveals no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics among all the subjects. ANOVA was used to compare the ages of the three groups and revealed no significant differences among the HC group (40.46 ± 12.12), AN group (41.13 ± 11.76), and AUD group (43.53 ± 12.08) (F = 0.271, P > 0.05). Notably, all the subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups were male and of Han ethnicity, with no differences in sex or ethnicity.

Single-factor analysis of variance was conducted to assess various indicators in plasma, yielding the following results. Across subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups, as alcohol intake increased, the PAI-1 content significantly increased, with the effect of alcohol intake on the PAI-1 level proving statistically significant (F = 23.915, P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). Similarly, in the plasma of the subjects within these groups, alcohol intake was associated with a notable decrease in tPA content, with the effect being statistically significant (F = 64.791, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B).

A B

Results of PAI-1 and tPA levels among the three groups. (A): Significant differences in the PAI-1 levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups were observed through pairwise comparisons (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase in the PAI-1 level with increasing alcohol intake. (B): Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in tPA levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), with a notable decrease in tPA levels observed as alcohol intake increased. The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of the data for the three groups. * denotes P < 0.05 between two groups.

To determine the effects of alcohol on PAI-1 and tPA protein levels, this study investigated the influence of alcohol on ProBDNF cleavage by examining mBDNF and ProBDNF levels within the pathway. In the plasma of HCs, AN patients, and AUD patients, the level of mBDNF decreased significantly with increasing alcohol intake (F = 96.270, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Conversely, the level of ProBDNF increased significantly with increasing alcohol intake (F = 23.992, P < 0.05; Fig. 5B).

A B

Results of mBDNF and proBDNF levels among the three groups. (A): Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in mBDNF levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), with a significant decrease in mBDNF levels as alcohol intake increased. (B): Significant differences in proBDNF levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups were observed through pairwise comparisons (P < 0.05), with a significant increase in proBDNF levels as alcohol intake increased. The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of the data for the three groups. * denotes P < 0.05 between two groups.

In addition to the observed alterations in mBDNF and ProBDNF levels, the receptor levels of TrkB and P75NTR were assessed to determine whether mBDNF and ProBDNF exert their effects through the corresponding receptors. In the plasma of subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups, the level of TrkB decreased significantly with increasing alcohol intake (F = 37.857, P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). Conversely, the level of P75NTR increased significantly with increasing alcohol intake (F = 41.122, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B).

A B

TrkB and p75NTR levels in the three groups. (A): Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in TrkB levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), with a significant decrease in TrkB levels as alcohol intake increased. (B): Significant differences in p75NTR levels (pg/ml) among the HC, AN, and AUD groups were observed through pairwise comparisons (P < 0.05), with a significant increase in p75NTR levels as alcohol intake increased. The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of the data for the three groups. * denotes P < 0.05 between two groups.

These findings clearly revealed that increasing alcohol intake significantly inhibited tPA, mBDNF, and TrkB and significantly activated PAI-1, ProBDNF, and P75NTR. Further, one-way ANOVA was used to compare the ratios of tPA/PAI-1, mBDNF/ProBDNF, and TrkB/P75NTR in the plasma of subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups. The differences in the tPA/PAI-1 ratios among the HC, AN, and AUD groups were statistically significant (F = 60.962, P < 0.05; Fig. 7A). Similarly, the difference in the ratio of mBDNF/ProBDNF among subjects in the HC, AN, and AUD groups was statistically significant (F = 34.740, P < 0.05; Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the difference in the ratio of TrkB/P75NTR among the HC, AN, and AUD groups was statistically significant (F = 33.142, P < 0.05; Fig. 7C).

A B C

Baseline ratios of tPA/PAI-1, mBDNF/ProBDNF, and TrkB/P75NTR in the HC, AN, and AUD groups were subjected to statistical analysis via ANOVA. (A): Significant differences in the tPA/PAI-1 ratio were observed pairwise between the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), with a significant decrease as alcohol intake increased. (B): Significant differences in the mBDNF/ProBDNF ratio were observed through pairwise comparisons between the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), indicating a significant decrease with increasing alcohol intake. (C): Significant differences in the TrkB/P75NTR ratio were observed pairwise between the HC, AN, and AUD groups (P < 0.05), with a significant decrease as alcohol intake increased. The HC group represents the absolute nondrinking group, the AN group represents the nonaddictive drinking group, and the AUD group represents the alcohol use disorder group. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and ANOVA was applied for statistical analysis of the data for the three groups. * denotes P < 0.05 between two groups.

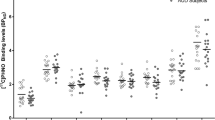

One-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze the plasma indicators of subjects in the AUD group at weeks 0, 2, and 4 after abstinence treatment. The results for PAI-1 and tPA are shown in Fig. 8A. There was a significant difference in the impact of the PAI-1 level after abstinence treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 10.748, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in the PAI-1 level were detected between weeks 0 and 2 and between weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). Conversely, no significant difference in the PAI-1 level was observed between weeks 2 and 4 (P > 0.05). There was a significant difference in the impact of tPA levels after abstinence treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 6.920, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in tPA levels were observed between weeks 0 and 2 and between weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). However, there was no statistically significant difference in tPA levels between weeks 2 and 4 (P > 0.05). The results for mBDNF and ProBDNF are shown in Fig. 8B. Significant differences were observed in the impact of mBDNF levels in patients after abstinence treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 24.346, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in mBDNF levels were noted between patients at 0 and 2 weeks, 0 and 4 weeks, and 2 and 4 weeks (P < 0.05). Similarly, significant differences were observed in the impact of ProBDNF levels after abstinence treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 in patients (F = 33.698, P < 0.05). Significant differences in ProBDNF levels were notably evident between patients at weeks 0 and 2, 0 and 4, and 2 and 4 (P < 0.05). The results concerning TrkB and P75NTR are shown in Fig. 8C. Significant differences in TrkB levels were detected in patients after abstinence at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 10.166, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in TrkB levels were noted between patients at weeks 0 and 2 and between weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). However, the difference between weeks 2 and 4 was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Similarly, significant differences were observed in the impact of P75NTR levels after abstinence treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 in patients (F = 10.944, P < 0.05). Notably, significant differences in P75NTR levels were evident between patients at weeks 0 and 2, as well as at weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). Conversely, the difference between weeks 2 and 4 was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

A B C

The plasma indicator results of the AUD group at weeks 0, 2, and 4 after abstinence treatment. (A): PAI-1 levels in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly higher than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. Conversely, tPA levels in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly lower than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant decrease after abstinence. (B): mBDNF levels in the plasma of the AUD group were significantly greater at weeks 2 and 4 than at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. The levels of proBDNF in the plasma of the AUD group were significantly lower at weeks 2 and 4 than at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant decrease after abstinence. (C): The levels of TrkB in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly lower than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant decrease after abstinence. The levels of P75NTR in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly greater than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. The HC (n = 15), AN (n = 15), and AUD (n = 15) groups are represented as the means ± standard deviations; * represents P < 0.05 between groups.

Based on the above results, the levels of PAI-1, tPA, mBDNF, ProBDNF, TrkB and P75NTR were affected following alcohol abstinence. Therefore, this study used one-way repeated-measures ANOVA to further compare the ratios of tPA/PAI-1, mBDNF/ProBDNF, and TrkB/P75NTR in the plasma of subjects at weeks 0, 2, and 4. The results of tPA/PAI-1 are depicted in Fig. 9A. Significant differences were observed in the effect on tPA/PAI-1 levels in patients after treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 17.948, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in tPA/PAI-1 levels were noted between patients at weeks 0 and 2, as well as at weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). However, the difference between weeks 2 and 4 was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The mBDNF/ProBDNF results are shown in Fig. 9B. Significant differences in mBDNF/ProBDNF levels in patients were detected after treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 41.425, P < 0.05). Notably, significant differences in mBDNF/ProBDNF levels were evident in patients between weeks 0 and 2, 0 and 4, and 2 and 4 (P < 0.05).The TrkB/P75NTR results are shown in Fig. 9C. Significant differences in TrkB/P75NTR levels in patients were measured after treatment at weeks 0, 2, and 4 (F = 16.310, P < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences in TrkB/P75NTR levels were noted between patients at weeks 0 and 2, as well as at weeks 0 and 4 (P < 0.05). However, the difference between weeks 2 and 4 was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

A B C

The ratios of tPA/PAI-1, mBDNF/ProBDNF, and TrkB/P75NTR in the AUD group at weeks 0, 2, and 4 were analyzed via one-way repeated-measures ANOVA. (A): The ratios of tPA/PAI-1 in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly greater than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. (B): The ratios of mBDNF/ProBDNF in the plasma of the AUD group were significantly greater at weeks 2 and 4 than at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. (C): The ratios of TrkB/P75NTR in the plasma of the AUD group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly greater than those at week 0 (P < 0.05), indicating a significant increase after abstinence. The HC (n = 15), AN (n = 15), and AUD (n = 15) groups are represented as means ± standard deviations; * represents P < 0.05 between groups.

Discussion

This clinical study revealed a correlation between the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway and mBDNF production in AUD patients. Alcohol disrupts the equilibrium of the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway and inhibits the efficiency of the cleavage of ProBDNF to mBDNF, resulting in a significant reduction in mBDNF production. Moreover, mBDNF production increases significantly after abstinence from alcohol. These findings provide new insights into the biological changes caused by AUD and the reversal of these changes after abstinence.

Effects of alcohol use on the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway

In this study, increased alcohol intake was associated with a significant increase in PAI-1 and a significant decrease in tPA. Previous studies have focused on the relationships among PAI-1, tPA and thrombosis, and clinical observations have revealed an increased incidence of thrombotic events in patients with AUD25. This may be because alcohol, as a toxin, affects several organs and systems when it enters the body. This finding suggests that when treating AUD, it is important to focus not only on the patient’s abstinence symptoms but also on the patient’s coagulation function to prevent cardiovascular disease.

While PAI-1 and tPA are conventionally associated with thrombus formation, recent clinical investigations have highlighted their involvement in the cleavage process of proBDNF to mBDNF17,26. These studies indicated that there was a significant increase in ProBDNF expression, accompanied by a significant decrease in mBDNF levels, which may be related to an increase in alcohol intake. Previous studies have demonstrated a similar pattern in AUD patients, where ProBDNF expression increases significantly, whereas the mBDNF level decreases notably27. Additionally, animal studies have indicated that, after alcohol exposure, proBDNF protein levels increase in the nucleus accumbens, cortex, and amygdala22, and BDNF levels in the serum level of rats is negatively correlated with alcohol intake28, which is consistent with the results of the present study.

Further, distinguishing the roles of ProBDNF-P75NTR and mBDNF-TrkB in AUD is crucial, as their binding has opposite biological effects29. This study further revealed that P75NTR was significantly upregulated, whereas TrkB was significantly downregulated, which may be related to the increase in alcohol intake. These results corroborate previous findings, indicating significant enhancement of the ProBDNF-P75NTR pathway and suppression of the mBDNF-TrkB pathway in patients with AUD, suggesting a disruption in neurotrophic and neurodegenerative balance. Overall, these findings indicate that alcohol inhibits the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF through the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway.

Effects of alcohol abstinence on the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway

Clinical studies have shown that the PAI-1 level decreases after alcohol intake ceases in patients with AUD, thereby reducing the risk of thrombotic events30. This study confirms that there is a significant decrease in PAI-1 level alongside a significant increase in tPA within the body after alcohol abstinence treatment. However, beginning in the second week of abstinence, both tPA and PAI-1 enter a plateau phase, whereas ProBDNF and mBDNF continue to exhibit changing trends. These findings suggest that although tPA and PAI-1 reach a steady state after the second week of abstinence, other pathways may promote the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF, necessitating further investigation.

This study revealed that elevated tPA levels are associated with alcohol abstinence in AUD patients, which also promotes the cleavage efficiency of ProBDNF, leading to a significant increase in mBDNF levels. Previous studies have reported a decrease in ProBDNF levels and an increase in mBDNF levels after alcohol cessation, which is consistent with our findings31. Further, the mean mBDNF level is lower in alcohol-dependent patients with a positive family history of alcohol dependence than in those with a negative family history32. Animal experiments have shown that the intracerebral injection of mBDNF into the prefrontal cortex of alcohol-dependent mice can reduce alcohol intake33. Although our study revealed a significant rebound in the mBDNF level by the fourth week of abstinence, it did not reach the levels observed in the normal control group. This may contribute to persistent alcohol cravings after abstinence treatment or even serve as a primary factor in patient relapse, necessitating further research and discussion.

This study also revealed that decreased P75NTR levels and increased TrkB levels are associated with abstinence in AUD patients, which is consistent with previous research results31. However, the TrkB level appeared to reach stability in the second week, with no significant changes between the second and fourth weeks. These findings suggest that despite the significant increase in mBDNF levels during the fourth week, TrkB receptors remain relatively stable, thus limiting the therapeutic effect after abstinence. Therefore, increasing the level of TrkB may further improve the effectiveness of abstinence treatment and facilitate overall recovery.

In conclusion, this clinical study reveals the effects of alcohol intake and abstinence on the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF via the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway. Although the levels of PAI-1 and tPA were stable after the second week, the levels of mBDNF and ProBDNF at the fourth week were significantly different from those at the second week. These findings suggest that alternative pathways may control the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF. Previous studies have shown that in addition to PAI-1 and tPA, extracellular proteases are also the major pathways to produce ProBDNF. For example, matrix metalloproteinase 9 is also a major pathway by which extracellular proteases cleave ProBDNF to generate mBDNF34. Further exploration of other possible mechanistic pathways is needed in the future to provide a new theoretical basis for the treatment of AUD.

Limitations

Although this clinical study revealed that alcohol inhibits the maturation of mBDNF through the PAI-1→mBDNF signaling pathway, several limitations remain. First, a single sex (only males) and relatively small sample sizes were included within each experimental group. Second, the observational period of four weeks, inherent to this clinical approach, may not accurately capture the full spectrum of long-term effects. Third, the administration of oral oxazepam to all enrolled patients posthospitalization introduces an additional variable, potentially confounding the influence of medication and alcohol cessation on the measured parameters. Nonetheless, our findings are highly instructive for AUD clinical treatment.

Conclusion

The results of this clinical study suggest that AUD inhibits the conversion of ProBDNF to mBDNF via the PAI-1→mBDNF pathway and that the production of mBDNF significantly increases after abstinence treatment. Therefore, the PAI-1→mBDNF cleavage pathway is intricately linked to AUD and its treatment during abstinence. The development of PAI-1 inhibitors is expected to increase the level of mBDNF in individuals with AUD, which may serve to counteract AUD-induced damage. More importantly, the strategic approach to the future application of PAI-1 inhibitors has great potential for therapeutic intervention, providing a pathway for reversing the damage caused by alcohol and potentially serving as a key strategy for preventing relapse in this patient.

Data availability

This article and its supplementary information files contain entire data generated or analyzed during the course of this investigation and are made available to the readers.

References

Glantz, M. D. et al. The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: findings from the World Mental Health surveys. Addict. Behav. 102, 106128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106128 (2020).

Tomasi, D. et al. Accelerated aging of the Amygdala in Alcohol Use disorders: relevance to the Dark side of addiction. Cereb. Cortex. 31, 3254–3265. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab006 (2021).

Janssen, G. T. L., Egger, J. I. M. & Kessels, R. P. C. Impaired Executive Functioning Associated with Alcohol-Related Neurocognitive Disorder including Korsakoff’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206477 (2023).

Charlton, A. J. et al. Chronic voluntary alcohol consumption causes persistent cognitive deficits and cortical cell loss in a rodent model. Sci. Rep. 9, 18651. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55095-w (2019).

Silva-Peña, D. et al. Alcohol-induced cognitive deficits are associated with decreased circulating levels of the neurotrophin BDNF in humans and rats. Addict. Biol. 24, 1019–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12668 (2019).

Shafiee, A. et al. Effect of alcohol on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) blood levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 17554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44798-w (2023).

Girard, M., Carrier, P., Loustaud-Ratti, V. & Nubukpo, P. BDNF levels and liver stiffness in subjects with alcohol use disorder: evaluation after alcohol withdrawal. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 47, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2020.1833211 (2021).

Girard, M., Labrunie, A., Malauzat, D. & Nubukpo, P. Evolution of BDNF serum levels during the first six months after alcohol withdrawal. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 21, 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2020.1733079 (2020).

Ornell, F. et al. Serum BDNF levels increase during early drug withdrawal in alcohol and crack cocaine addiction. Alcohol 111, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2023.04.001 (2023).

Kethawath, S. M., Jain, R., Dhawan, A., Sarkar, S. & Kumar, M. An observational study of serum brain derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with Alcohol Dependence during Withdrawal. J. Psychoact. Drugs 52, 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1795327 (2020).

Valerio, A. G. et al. Increase in serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels during early withdrawal in severe alcohol users. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 44, e20210254. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0254 (2022).

Wang, C. S., Kavalali, E. T. & Monteggia, L. M. BDNF signaling in context: from synaptic regulation to psychiatric disorders. Cell 185, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.003 (2022).

Diniz, C., Casarotto, P. C., Resstel, L. & Joca, S. R. L. Beyond good and evil: a putative continuum-sorting hypothesis for the functional role of proBDNF/BDNF-propeptide/mBDNF in antidepressant treatment. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 90, 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.001 (2018).

Jiang, H. et al. The serum protein levels of the tPA-BDNF pathway are implicated in depression and antidepressant treatment. Transl Psychiatry 7, e1079. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.43 (2017).

Dai, W. et al. Intracellular tPA-PAI-1 interaction determines VLDL assembly in hepatocytes. Science. 381, eadh5207. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh5207 (2023).

Gerenu, G. et al. Modulation of BDNF cleavage by plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1 contributes to Alzheimer’s neuropathology and cognitive deficits. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 991–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.01.023 (2017).

Angelucci, F., Veverova, K., Katonová, A., Vyhnalek, M. & Hort, J. Serum PAI-1/BDNF ratio is increased in Alzheimer’s Disease and correlates with Disease Severity. ACS Omega. 8, 36025–36031. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04076 (2023).

Sasaki, A., Kurisu, A., Ohno, M. & Ikeda, Y. Overweight/obesity, smoking, and heavy alcohol consumption are important determinants of plasma PAI-1 levels in healthy men. Am. J. Med. Sci. 322, 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200107000-00004 (2001).

Delahousse, B. et al. Increased plasma fibrinolysis and tissue-type plasminogen activator/tissue-type plasminogen activator inhibitor ratios after ethanol withdrawal in chronic alcoholics. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 12, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001721-200101000-00009 (2001).

Kethawath, S. M., Jain, R., Dhawan, A. & Sarkar, S. A review of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in alcohol-dependent patients: current understanding. Indian J. Psychiatry. 62, 15–20. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_134_19 (2020).

Costa, M. A., Girard, M., Dalmay, F. & Malauzat, D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum levels in alcohol-dependent subjects 6 months after alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 35, 1966–1973. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01548.x (2011).

Popova, N. K. et al. On the interaction between BDNF and serotonin systems: the effects of long-term ethanol consumption in mice. Alcohol. 87, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.04.002 (2020).

Logrip, M. L., Barak, S., Warnault, V. & Ron, D. Corticostriatal BDNF and alcohol addiction. Brain Res. 1628, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.03.025 (2015).

Geoffroy, H. & Noble, F. BDNF during withdrawal. Vitam. Horm. 104, 475–496 (2017).

Zöller, B., Ji, J., Sundquist, J. & Sundquist, K. Alcohol use disorders are associated with venous thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 40, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-015-1168-8 (2015).

Hoirisch-Clapauch, S. Mechanisms affecting brain remodeling in depression: do all roads lead to impaired fibrinolysis? Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01264-1 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. ProBDNF/p75NTR/sortilin pathway is activated in peripheral blood of patients with alcohol dependence. Transl. Psychiatry. 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0015-4 (2018).

Ehinger, Y. et al. Differential correlation of serum BDNF and microRNA content in rats with rapid or late onset of heavy alcohol use. Addict. Biol. 26, e12890. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12890 (2021).

Pettorruso, M. et al. Enhanced peripheral levels of BDNF and proBDNF: elucidating neurotrophin dynamics in cocaine use disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 29, 760–766. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02367-7 (2024).

Mennesson, M. & Revest, J. M. Glucocorticoid-responsive tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and its inhibitor plasminogen activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1): relevance in stress-related Psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054496 (2023).

Zhou, L., Xiong, J., Gao, C., Bao, J. & Zhou, X. F. Early Alcohol Withdrawal Reverses the Abnormal Levels of proBDNF/mBDNF and their Receptors. (2021).

Joe, K. H. et al. Decreased plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 1833–1838. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00507.x (2007).

Haun, H. L. et al. Increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in medial prefrontal cortex selectively reduces excessive drinking in ethanol dependent mice. Neuropharmacology. 140, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.07.031 (2018).

Go, B. S., Sirohi, S. & Walker, B. M. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in negative reinforcement learning and plasticity in alcohol dependence. Addict. Biol. 25, e12715. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12715 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research assistants and all the staff of the Science and Technology Bureau of Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, China. This research was funded in part by the Jinhua Key Science and Technology Program Projects, grant numbers 2023-3-154 and 2023-3-157.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.,G.L.,S.L.,designed this study and wrote the manuscript. X.X.,D.Z.,W.W.,Y.H.and X.L.performed the experiments.N.J. organizes data. All authors read and provided input on the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Xie, X., Zhao, D. et al. Alcohol use disorder disrupts BDNF maturation via the PAI-1 pathway which could be reversible with abstinence. Sci Rep 14, 22150 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73347-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73347-2