Abstract

In contemporary floriculture, particularly within the cut flower industry, there is a burgeoning interest in innovative methodologies aimed at enhancing the aesthetic appeal and prolonging the postharvest longevity of floral specimens. Within this context, the application of nanotechnology, specifically the utilization of silicon and selenium nanoparticles, has emerged as a promising approach for augmenting the qualitative attributes and extending the vase life of cut roses. This study evaluated the impact of silicon dioxide (SiO2-NPs) and selenium nanoparticles (Se-NPs) in preservative solutions on the physio-chemical properties of ‘Black Magic’ roses. Preservative solutions were formulated with varying concentrations of SiO2-NPs (25 and 50 mg L−1) and Se-NPs (10 and 20 mg L−1), supplemented with a continuous treatment of 3% sucrose. Roses treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs exhibited the lowest relative water loss, highest solution uptake, maximum photochemical performance of PSII (Fv/Fm), and elevated antioxidative enzyme activities. The upward trajectory of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in petals was mitigated by different levels of SiO2 and Se-NPs, with the lowest H2O2 and MDA observed in preservatives containing 50 mg L−1 SiO2- and 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs at the 15th day, surpassing controls and other treatments. Extended vase life and a substantial enhancement in antioxidative capacity were noted under Se and Si nanoparticles in preservatives. The levels of total phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanin increased during the vase period, particularly in the 50 and 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs. Petal carbohydrate exhibited a declining trend throughout the longevity, with reductions of 8% and 66% observed in 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs and controls, respectively. The longest vase life was achieved with Se-NPs (20 mg L−1), followed by SiO2-NPs (50 mg L−1) up to 16.6 and 15th days, respectively. These findings highlight the significant potential of SiO2- and Se-NPs in enhancing the vase life and physiological qualities of ‘Black Magic’ roses, with SiO2-NPs showing broad-spectrum efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Roses hold significant prominence in floriculture, being traded globally as both potted and cut flowers, with a substantial worldwide demand1,2. The paramount objectives in rose cut flower production include achieving high yield, maintaining acceptable quality, and ensuring an extended vase life. Attaining these goals is contingent upon the pre-harvest nutritional status of the plant, although the composition of chemicals in vase solutions also plays a crucial role. The longevity of a flower is a pivotal quality trait, influencing consumer demand and the overall value of cut flowers. Well-established factors contributing to the abbreviated vase life of cut flowers include bacterial occlusion of xylem vessels3, physiological responses induced by cutting4, and air embolism5. Over time, various compounds, such as 8-HQS, 8-HQC, Ag₂S₂O₃, CuSO₄, AgNO₃, Al₂(SO₄)₃, and C₂H₆O, have been utilized as antimicrobial agents in vase solutions6,7. The inclusion of sugar in preservatives is of paramount importance, as carbohydrates play a pivotal role in supplying energy to petals, positively influencing metabolic processes, expansion, pigmentation, longevity, prevention of ethylene biosynthesis, and hydraulic balance maintenance8. The integration of nanotechnology, particularly in conjunction with nutrient elements, represents a noteworthy advancement in preserving quality and enhancing the longevity of ornamentals9.

In the exploration conducted by Rafi and Ramezanian10, the effectiveness of silver nanoparticles and S-carvone in extending the vase life of cut roses (‘Avalanche’ and ‘Fiesta’) was scrutinized. The administration of nano silver treatments demonstrated a significant enhancement in postharvest longevity through the mitigation of microbial proliferation and the optimization of water relations. Notably, the most efficacious results were observed with the application of nano silver at a concentration of 200 mg L−1, which facilitated an extended vase life of 18 days. The association between flower longevity and the potential for scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) by various chemicals in vase solutions is emphasized in existing literature11. A previous study on R. hybrida ‘Black Magic’ demonstrated that a preservative solution containing 10 mg L−1 chitosan nanoparticles effectively extended the longevity of these roses by 15 days compared to controls12. Silicon (Si), recognized as an indispensable plant nutrient abundant in soil, elicits alterations in plant morphology, anatomy, physiological processes, and metabolic pathways13. Researchers attribute these changes to the efficacy of silicon in maintaining plant hydraulic balance, activating oxidative enzymes, promoting photoassimilation, facilitating nutrient adsorption, enhancing ion mobility in plant tissues, regulating gene expression, and balancing hormonal activity14. Evaluation of various Si levels (0, 200, 400, and 800 g L−1) during the pre-harvest stage revealed significant impacts on the characteristics and vase life of cut roses. Silicon treatment, particularly at an application of 800 g L−1, resulted in reduced water loss and sustained petal water content. Additionally, this concentration led to a decline in peroxidase enzyme activity at both harvest and the conclusion of the vase life, while the application of 200 g L−1 yielded maximum peroxidase activity 4 and 6 days after storage15. On the other hand, selenium (Se), a common nutrient in soil, has garnered recent recognition for its pivotal role in defense systems, antioxidant activity, and hormonal balance in plants16. Moderate Se doses have been reported to enhance plant performance and antioxidative defense systems, along with modulating hormonal status17. The synergistic impact of Se and Si has been demonstrated to increase trichome development18. The efficiency of Se in scavenging ROS through the activation of antioxidative enzymes has been substantiated across various plants19,20. Lu et al.21 highlighted that Na2SeO3 increased the activity of superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, glutathione reductase, dehydroascorbate reductase, and monodehydroascorbate reductase in Lilium longiflorum during vase life. Specifically, increments in ascorbate peroxidase, dehydroascorbate reductase, and monodehydroascorbate reductase activities were responsible for H2O2 scavenging22.

In contemporary floriculture, particularly within the cut flower industry, there is a burgeoning interest in innovative methodologies aimed at enhancing the aesthetic appeal and prolonging the postharvest longevity of floral specimens. Within this context, the application of nanotechnology, specifically the utilization of silicon and selenium nanoparticles, has emerged as a promising approach for augmenting the qualitative attributes and extending the vase life of cut roses. This growing focus on nanotechnology in horticulture is part of a broader trend in agricultural sciences, where nanoparticles are being explored for their multifaceted benefits across various plant species and cultivation systems. The potential of nanoparticles in plant science extends far beyond cut flower preservation. Silicon nanoparticles, for instance, have demonstrated significant efficacy in enhancing plant growth, stress tolerance, and disease resistance in diverse crops23. These nanoparticles can optimize plant physiological processes, including photosynthesis, and stimulate the synthesis of antioxidant compounds, thereby fortifying plant defense mechanisms against various biotic and abiotic stresses. In the domain of plant tissue culture, nanoparticles have shown remarkable potential in mitigating biological contamination and enhancing organogenic regeneration, as evidenced in banana cultures24. This application not only improves the success rate of micropropagation but also potentially reduces the reliance on chemical sterilants, offering a more sustainable approach to plant biotechnology. Furthermore, the synergistic application of zinc oxide and silicon nanoparticles has been reported to significantly improve salt stress resistance and annual productivity in mango trees25. These nanoparticles were found to enhance photosynthetic efficiency, water relations, and antioxidant enzyme activities, leading to improved fruit yield and quality under saline conditions. Notably, foliar application of nanoparticles has been found to alleviate chilling stress effects on photosynthesis and photoprotection mechanisms in sugarcane26. The nanoparticles enhanced the activity of key enzymes involved in carbon fixation and improved the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus under low-temperature stress.

Maintaining the post-harvest quality of cut roses remains a significant challenge for the floriculture industry. Recent studies indicate that the application of silicon and selenium nanoparticles has the potential to extend vase life and enhance flower quality. These elements positively affect plant physiology by providing protection against oxidative stress and improving water uptake. However, further research is needed on factors such as application methods, dosage, and cost-effectiveness to effectively integrate these nanoparticles into commercial practices. In light of previous literature pointing to the limited longevity of cut roses, specifically ‘Black Magic’27, the primary objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of Selenium and SiO2 nanoparticles on the hydraulic relations and biochemical status of R. hybrida ‘Black Magic’ petals. This research seeks to provide a comprehensive exploration into the fundamental mechanisms that underlie the application of nanoparticles, aiming to contribute to a more profound understanding of how these nanoparticles can effectively enhance the longevity of rose flowers.

Results

Vase life, microbial contamination, physiological and biochemical attributes

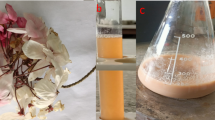

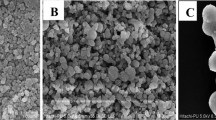

The results of the vase life experiment, as illustrated in Fig. 1a-b, demonstrate significant variations in cut rose longevity across different treatments. The most pronounced extension of vase life was observed in roses treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs, which exhibited a mean lifespan of 16.6 days. This was followed by roses treated with 50 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs, which maintained quality for an average of 15 days. Treatments with lower concentrations of nanoparticles also yielded substantial improvements in longevity, with 10 mg L−1 Se-NPs and 25 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs extending vase life to 13.6 and 11 days, respectively. In contrast, control flowers maintained in distilled water displayed the shortest vase life of 7.3 days. Microbial contamination analyses, presented in Fig. 2a and b, reveal a marked reduction in bacterial proliferation across various SiO2- and Se-NPs treatments. The control treatment exhibited the highest mesophilic bacterial count, reaching 4.24 Log CFU mL−1. Conversely, the lowest bacterial count of 0.93 Log CFU mL−1 was recorded in the 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs treatment (T5). The 50 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs treatment (T3) also demonstrated significant antimicrobial efficacy, with a contamination level of 1.36 Log CFU mL−1. Microscopic examination of the vase solution, as shown in Fig. 2c, indicated that the predominant microbial contaminants were Gram-negative bacilli. This observation provides insight into the specific types of microorganisms present in the vase solution and potentially affecting cut flower longevity. These results collectively demonstrate the efficacy of Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs in extending the vase life of cut roses and reducing microbial contamination in vase solutions, with the most pronounced effects observed at concentrations of 20 mg L−1 for Se-NPs and 50 mg L−1 for SiO2-NPs.

Effect of various levels of SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs on (a) Microbial accumulation in vase solution at 7th day; (b) Different microbial populations on different vase solutions on the 7th day, and (c) Microscopic observation of T1 (distilled water + 3% sucrose) and T5 (containing 20 mg L-1 Se-NPs + 3% sucrose).

The analysis of solution uptake, as depicted in Fig. 3, reveals a consistent decrease in water uptake across all treatments throughout the experiment. Notably, the control flowers exhibited the lowest water uptake on the final day of vase life. The maximum solution uptake was observed in roses treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs, maintaining 5.6 times higher water uptake than the controls at the 15th day. Interestingly, this performance was statistically comparable to the SiO2-NPs treatment at 50 mg L−1 throughout the vase life. Nano particle treatments, in general, exhibited superior water uptake compared to the control, particularly in the initial 4 days of longevity. Regarding Membrane Stability Index (MSI %), the incorporation of SiO2 and Se nanoparticles into vase solutions demonstrated a notable reduction in electrolyte leakage, signifying enhanced membrane stability in petals compared to the control group. While all petals exhibited the highest MSI at the harvest day, a gradual decrease occurred until the conclusion of the vase life. Interestingly, the petals with the firmest membranes, indicated by the lowest electrolyte leakage percentage, were those immersed in vase solutions containing 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles at the 8th day. However, no significant differences in electrolyte leakage were observed between treatments and controls on the 15th day (Fig. 4).

The analysis of Relative Fresh Weight (RFW) and Relative Water Content (RWC %), as presented in Fig. 5a, reveals an initial increase in RFW of flowers at day 4, followed by a progressive decline until the termination of vase life. The introduction of rose cut flowers into vase solutions containing SiO₂ and Se nanoparticles resulted in a significant reduction in RFW by day 15 relative to the control specimens. Despite this overall decrease in RFW, petals subjected to treatments with 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles exhibited the lowest RFW on day 15, demonstrating reductions of 13% and 23%, respectively, in comparison to the control group. Furthermore, RWC, serving as an indicator of hydration status, was observed to be at its peak at the time of harvest and subsequently underwent a gradual decline across all treatments throughout the vase life period. Notably, petals maintained in solutions containing 50 mg L−1 SiO₂ nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles retained a higher relative water content on the 15th day when compared to both the control group and other treatment conditions (Fig. 5b).

Analysis of leaf chlorophyll fluorescence parameters revealed distinct trends across treatments. The maximal fluorescence (Fm) exhibited a declining pattern throughout the longevity of flowers in the control group and those treated with 25 mg L−1 SiO₂ nanoparticles and 10 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles. Conversely, specimens treated with 50 mg L−1 SiO₂ nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles demonstrated an initial increase in Fm at day 4 of vase life, followed by a subsequent decrease. Notably, flowers in vase solutions containing 50 mg L−1 SiO₂ nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles exhibited significantly elevated Fm values compared to the control and other treatments on day 15. Among the treatments, the highest Fm values were observed in flowers immersed in 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, the Fv/Fm ratio, an indicator of the maximal photochemical efficiency of Photosystem II (PSII), displayed a decreasing trend during the vase life period. Flowers maintained in vase solutions with 50 mg L−1 SiO₂ nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles retained higher Fv/Fm ratio values compared to those recorded in the controls at the conclusion of the vase life, as illustrated in Fig. 6b.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) exhibited an increasing trend, with values exceeding those recorded at harvest in all treatments, except for the control group maintained in distilled water. In contrast to the control, all other treatments demonstrated an initial elevation in SOD activity, followed by a subsequent decrease throughout the vase life period. Notably, flowers preserved in 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles exhibited the highest SOD activity values throughout the entire vase life compared to all other treatments (Fig. 7). Catalase (CAT) activity increased across all treatments, with values surpassing those recorded at harvest and in comparison to the controls. This upward trend in CAT activity was particularly pronounced in rose flowers immersed in 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles, reaching the highest CAT activity value (3.57) in petals at the conclusion of the vase life compared to the control and other treatments, as depicted in Fig. 8.

The activity of POX exhibited significant variations among treatments. Specifically, the POX activity in treatments with 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles and 10 and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles was notably higher than that in the control and 25 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles treatments. Moreover, the POX activity in the 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles treatment was substantially higher than that in the control treatment, exceeding the POX activity in the 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles treatment by 26% on day 15 (Fig. 9).

The activity of PPO displayed an upward trend on the 8th day across all treatments, followed by a subsequent decrease on day 15. Notably, rose flowers preserved in vase solutions containing 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles and 20 mg L−1 Se nanoparticles exhibited increased PPO activity, surpassing that in the 50 mg L−1 SiO2 nanoparticles treatment by 21% on day 15 (Fig. 10). As depicted in Fig. 11, the activity of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) exhibited an increasing trend specifically in Se-NPs treatments until the conclusion of the vase life. In SiO2-NPs treatments, an increase was observed on day 4, followed by a decrease until the end of the vase life, although the values remained higher than those recorded at the beginning of the experiments.

As illustrated in Fig. 12a, H₂O₂ levels demonstrated an upward trend throughout the vase life, with fold increases of 2.1, 1.9, 1.3, 1.6, and 1.8 observed in control, SiO₂-NPs (25 and 50 mg L−1), and Se-NPs (10 and 20 mg L−1) treatments, respectively. Notably, flowers preserved in 50 mg L−1 SiO₂-NPs exhibited the least significant increase in H₂O₂ compared to control and other treatments. A comparable increasing pattern was observed in the malondialdehyde (MDA) levels of rose petals during vase life (Fig. 12b), with the distinction that the lowest MDA levels were associated with flowers maintained in vase solution containing 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs, which increased by 1.6-fold compared to the control (2.7-fold). Figure 13a demonstrates that various treatments significantly enhanced phenol content compared to the control, with the most substantial increase observed in the 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs treatment. The total phenol content in rose petals at day 15 was 13.35 mg GAE g−1 FW, while it was 6.03 mg GAE g−1 FW in control flowers. Flowers preserved in 50 mg L−1 SiO₂-NPs also exhibited an increase in petal total phenolic content (TPC) by 1.4-fold compared to controls at the conclusion of the vase life. Figure 13b illustrates a similar increasing trend in the total flavonoid content (TFC) of rose petals. The most significant increase in TFC was recorded in flowers preserved in solutions containing 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs, followed by 25 mg L−1 SiO₂-NPs, with 2.1-fold and 1.9-fold increases, respectively, compared to controls.

Figure 14 shows that petal total carbohydrate decreased during vase life, with control flowers having the lowest (2.3 mg g−1FW) and preservative solution containing 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs having the highest (6.2 mg g−1FW) total carbohydrate in petals at the last day of longevity. Regarding Fig. 15, anthocyanin levels in petals increased during vase life. Vase solution containing 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs had the highest anthocyanin value (8.12 mg g−1FW), while controls had the lowest value (0.64 mg g−1FW) compared to the values at harvest day.

Pearson correlation

The Pearson correlation analysis, as depicted in Fig. 16, revealed a complex network of relationships among the measured physiological and biochemical parameters in the study. A strong positive correlation is observed between SPAD values, Total Phenolic Content (TPC), and carbohydrate levels. Conversely, Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) contents exhibit negative correlations with carbohydrate levels, antioxidant enzyme activities (Superoxide Dismutase [SOD], Polyphenol Oxidase [PPO], Catalase [CAT], and Ascorbate Peroxidase [APX]), and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv, Fm, and Fv/Fm ). This inverse relationship indicated that increased oxidative stress markers (MDA and H₂O₂) are associated with decreased carbohydrate content, reduced antioxidant enzyme activity, and impaired photosynthetic efficiency. Furthermore, the analysis revealed positive correlations between antioxidant enzyme activities and the Membrane Stability Index (MSI). This association suggested that enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity contributes to maintaining membrane integrity under stress conditions. The Relative Water Content (RWC) shows positive correlations with MSI and several other parameters, indicating its importance in overall plant physiological status. These intricate correlations showed the complex interplay between various physiological and biochemical processes in response to the experimental treatments, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms of stress tolerance and senescence regulation in the studied plant system.

Pearson correlation analysis of SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs treatment and variable trait relationship. Heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficient (r) values of variable traits, wherethe colored scale indicates the positive (green) or negative (orange) correlation and the ‘r’ coefficient values (r = -1.0 to 1.0).

Discussion

Vase life, microbial contamination, and physiological traits

The present investigation elucidates the efficacy of selenium nanoparticles (Se-NPs) and silicon dioxide nanoparticles (SiO2-NPs) in augmenting the postharvest longevity and quality attributes of Rosa hybrida cv. Black Magic. The results demonstrate a significant extension of vase life in cut roses treated with these nanoparticles, particularly at higher concentrations, corroborating previous findings on the beneficial effects of Se on cut snapdragon flowers26. The observed prolongation of vase life can be attributed to several interconnected physiological mechanisms. Primarily, the maintenance of favorable water relations appears to be a crucial factor. The gradual decline in water balance observed in treated flowers, as opposed to the rapid decline in control specimens, suggests an enhanced ability to regulate water uptake and transpiration. This is further substantiated by the significantly higher water uptake and maintenance in flowers treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs and 50 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs, resulting in elevated petal relative water content. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating Se’s role in improving water content through enhanced osmolyte production, such as proline, glycine betaine, and trehalose27,28. It is hypothesized that the improved water relations may be partially attributed to the potential antimicrobial properties of the nanoparticles, particularly SiO2-NPs, as previously observed in lisianthus vase solutions29. Although microbial accumulation was not directly assessed in this study, the reduction of microbial growth in the vase solution could contribute to maintaining vascular functionality and, consequently, water uptake. This hypothesis warrants further investigation through comprehensive microbial assays. Interestingly, the evaluation of membrane stability through electrolyte leakage did not reveal significant differences between treatments at the experiment’s conclusion. This outcome contrasts with some literature reporting reduced electrolyte leakage in Se-treated plants at lower concentrations. The discrepancy may be attributed to the variable responses of plants to nanoparticles, which are influenced by factors such as plant species, vegetative stage, and nanoparticle characteristics30. This shows the complexity of plant-nanoparticle interactions and highlights the importance of optimizing concentrations for specific applications. The most pronounced effect on photosynthetic efficiency was observed in leaves treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs. This enhancement in chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthetic potential aligns with previous findings on Se-NPs’ role in protecting chlorophyll from degradation through chloroplast enzyme protection and starch accumulation in chloroplasts31,32. The optimal concentrations of SiO2 and Se nanoparticles appear to be crucial in enhancing leaf pigments by fortifying antioxidant capacity and delaying leaf tissue senescence. The synergistic effects of Se and Si nanoparticles on photosynthetic efficiency can be explained by their respective roles in plant physiology. Selenium’s participation in chlorophyll biosynthesis33,34 and its protective effect on chloroplast enzymes35, combined with silicon’s necessity for Rubisco enzyme production36, collectively contribute to the improvement of photosynthesis in treated plants. It is postulated that these nanoparticles may modulate key enzymatic pathways involved in chlorophyll synthesis and carbon fixation, thereby enhancing overall photosynthetic efficiency. These findings suggest that the application of Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs in postharvest treatments for cut flowers may offer a promising approach to extending vase life and maintaining flower quality. The mechanisms underlying these effects appear to involve a complex interplay of improved water relations, potential antimicrobial activity, and enhanced photosynthetic efficiency. Further research is warranted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed physiological changes. Additionally, investigations into the potential synergistic effects of combining Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs at optimal concentrations could provide valuable insights for developing more effective postharvest treatments for cut flowers. Moreover, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses could shed light on the specific genes and proteins modulated by these nanoparticles, potentially revealing novel targets for enhancing cut flower longevity.

Antioxidative enzymes, biochemical solutes and anthocyanin

The present study elucidates the crucial role of antioxidative enzymes, particularly superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POX), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), in preserving post-harvest plant tissues and mitigating senescence, thereby significantly influencing the postharvest quality and vase life of cut flowers37. The observed augmentation in SOD, catalase (CAT), POX, polyphenol oxidase (PPO), and APX activities (Figs. 6–10) in response to varying concentrations of SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs treatments, compared to controls at harvest day, suggests an enhanced capacity for scavenging induced oxidative stress in Rosa hybrida cv. Black Magic. Notably, the antioxidative enzyme activities were most pronounced at 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs and 50 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs, with APX exhibiting higher activity at both Se-NPs concentrations (Fig. 10). This differential response of APX to Se-NPs concentrations warrants further investigation and may indicate a specific selenium-mediated regulation of APX gene expression or enzyme activation. The positive correlation between selenium concentration and increased APX activity suggests a potential mechanism by which APX contributes to delaying senescence and extending the display life of ‘Black Magic’ roses. It is hypothesized that the observed enhancement of postharvest quality in cut roses is attributable to the synergistic effect of elevated antioxidative enzyme activities and concurrent decreases in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (Fig. 11a and b). This dual action of enhancing antioxidant defenses while reducing oxidative stress markers provides a physiological basis for the extended vase life and improved flower quality. The differential stimulatory effects of Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs on antioxidative enzymes, particularly the more pronounced effect of Se-NPs on POX activity, suggest distinct mechanisms of action for these nanoparticles. While both demonstrate the ability to scavenge oxygen free radicals, the effective concentration range appears to differ, with SiO2-NPs requiring higher concentrations than Se-NPs for optimal effects. This disparity may be attributed to silicon’s role in enhancing plant defense systems through the formation of complexes with toxic substances in plant tissues14. The efficacy of Si-NPs in extending cut rose longevity through maintenance of membrane integrity, enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activity, and limitation of lipid peroxidation38 corroborates our findings. Similarly, the synergistic effects of Si/Se application reported by Golubkina et al.18 in Artemisia annua align with our observations, suggesting a potentially universal mechanism across diverse plant species. Furthermore, the observed enhancement of plant antioxidant status due to nano-Si application emerges as a potential mechanism for plant protection against abiotic stresses such as drought25 and salinity11. This finding has broader implications for understanding plant stress responses and developing strategies to mitigate environmental challenges in horticultural practices.nBased on these results, we propose a model wherein Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs act as signaling molecules, triggering a cascade of physiological responses that culminate in enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities. This model posits that the nanoparticles may interact with cellular receptors or directly modulate gene expression, leading to upregulation of antioxidant enzyme synthesis or activation of existing enzyme pools. The differential responses to varying concentrations of nanoparticles suggest a hormetic effect, where low to moderate concentrations elicit beneficial responses, while higher concentrations may be less effective or potentially detrimental. This hypothesis warrants further investigation through dose-response studies and molecular analyses of gene expression patterns.

The present study elucidates the dynamic changes in total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) during the vase life of R. hybrida cv. Black Magic under various nanoparticle treatments. The observed increase in TPC and TFC across all treatments, with notably higher accumulations in flowers treated with 20 and 50 mg L−1 Se-NPs and SiO2-NPs (Fig. 12a and b), corroborates previous findings by Mwangi and Bhattacharjee39 in cut rose cv. Golden Gate. This phenomenon suggests a potential adaptive response to postharvest stress, wherein phenolic compounds and flavonoids may serve as crucial antioxidants in mitigating oxidative damage during senescence. The differential efficacy of nanoparticle concentrations observed in this study aligns with the concept of hormesis in plant physiology. Low concentrations of selenium have been demonstrated to enhance oxidative stress tolerance by augmenting antioxidant capacity16. This hormetic effect is hypothesized to involve complex signaling cascades that upregulate antioxidant enzyme synthesis and activate stress response genes. Similarly, the optimal concentration of 40 mg L−1 nano-silicon identified for Eustoma grandiflorum29 suggests a species-specific threshold for nanoparticle-induced benefits. The role of sucrose in delaying wilting and regulating water balance40 provides a physiological basis for understanding the interplay between carbohydrate metabolism and flower senescence. It is postulated that the inclusion of nanoparticles in vase solutions may modulate sugar translocation and utilization, potentially enhancing the efficacy of exogenous sucrose applications. The necessity of antibacterial agents in vase solutions41 further underscores the complex interactions between microbial ecology, vascular function, and flower longevity. The preservation of higher carbohydrate levels in rose petals treated with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs (Fig. 13) suggests a selenium-mediated enhancement of carbohydrate metabolism or retention. This observation aligns with previous reports on the positive effects of sodium selenite on antioxidant enzyme activity and carbohydrate content in Lilium cut flowers21. We hypothesize that selenium may influence key enzymes involved in carbohydrate synthesis or degradation, potentially through post-translational modifications or gene expression regulation. The accumulation of anthocyanins, pivotal flavonoid pigments contributing to flower coloration, exhibited a treatment-dependent response (Fig. 14). The elevated anthocyanin levels observed in flowers treated with 50 and 20 mg L−1 SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs, respectively, corroborate previous findings on selenium-enhanced flavonoid and anthocyanin accumulation42. This phenomenon may be attributed to the activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, possibly through the modulation of key transcription factors or enzymes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. The multifaceted effects of SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs on the biochemical and physiological attributes influencing postharvest quality and vase life of cut roses suggest a complex network of interactions at the cellular and molecular levels. We propose a model wherein these nanoparticles act as elicitors, triggering stress response pathways that lead to enhanced antioxidant production, improved water relations, and delayed senescence. This model posits that the nanoparticles may interact with membrane-bound receptors or cellular signaling molecules, initiating cascades that ultimately result in transcriptional and metabolic changes conducive to extended flower longevity.

Conclusion

The application of Se-NPs at a concentration of 20 mg L−1 significantly enhanced the water balance of the cut rose variety ‘Black Magic.’ This enhancement was evidenced by improvements in water absorption, membrane stability index, mitigation of chlorophyll degradation, and up-regulation of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. Se-NPs at 20 mg L−1 led to a substantial extension of vase life, reaching up to 16.6 days, establishing it as a cost-effective and environmentally-safe agent for extending the floral longevity of cut roses. However, it is suggested that SiO2-NPs, particularly at concentrations higher than 50 mg L−1, may exhibit comparable effects to those observed with 20 mg L−1 Se-NPs, indicating a potential dose-dependent relationship. This observation implies that higher concentrations of SiO2-NPs might elicit similar benefits to the optimal concentration of Se-NPs. Moreover, our study provided evidence supporting the potential of Se-NPs to impede the senescence of cut rose flowers ‘Black Magic.’ This protective effect was manifested through the reduction of petal water loss, stimulation of antioxidant enzyme activities, and prevention of leaf chlorophyll degradation. In a broader context, SiO2 and Se nanoparticles have the potential to play a crucial role in enhancing the postharvest characteristics of various cut flowers. Their advantageous features, such as ease of application, non-toxicity, large surface area, durability, reduction of bacterial proliferation, prevention of ethylene biosynthesis, limitation of protein and chlorophyll degradation, and improvement of antioxidant enzyme activity, collectively contribute to mitigating the effects of oxidative stress during flower senescence. These findings underscore the significant role of SiO2 and Se nanoparticles in the floricultural industry, providing accessible, sustainable, and effective strategies for extending vase life and enhancing the overall quality of cut flowers.

Materials and methods

Plant material and treatments

The flowers of R. hybrida ‘Black Magic’ were sourced from a greenhouse in Tehran, Iran, adhering to established rose maturity indices47. Subsequently, the cut roses were re-trimmed to a standardized height of 40 cm and immersed in various preservative solutions containing SiO2-NPs (T2 = 25 and T3 = 50 mg L−1) and Se-Nps (T4 = 10 and T5 = 20 mg L−1), along with 3% sucrose, as a continuous treatment, with each treatment having three replications12. The SiO2 and Se-NPs were procured from the NANOSANY Corporation in Mashhad, Iran. For the control group, flowers were placed in distilled water (T1 = Distilled water). Throughout the experiment, the cut roses were stored in a cold room with a temperature of 10 ± 2°C, relative humidity of 60%, and a 12-h light period at an intensity of 15 µM m−2 s−1. To assess the impact of the preservative solutions, flowers were subjected to evaluations of their physiological and biochemical traits at specific sampling intervals of 0, 4, 8, and 15 days after harvest. This systematic approach allowed for a comprehensive analysis of how SiO2-NPs and Se-NPs, in conjunction with sucrose, influenced the key characteristics of R. hybrida ‘Black Magic’ flowers over the designated period.

Vase life and contamination

Vase life was determined by measuring the duration from the moment roses were introduced into different preservative solutions until signs of decay, such as shriveling, bluing, petal enrolling, and abscission, became evident48. To assess microbial contamination, one milliliter of vase solutions was sampled and diluted to a concentration of 104. Subsequently, these samples were cultured on a nutrient agar medium on the 7th day of the vase life, with each treatment replicated three times. The cultures were then incubated at 37ºC for 48 h to facilitate the detection and quantification of microbial contaminants. This methodology allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of both the longevity of the roses and the extent of microbial contamination within the preservative solutions.

Physiological and biochemical traits assay

The uptake of the preservative solution was measured at two-day intervals after the transfer of roses from the bucket to vases, employing the formula (1) as outlined by He et al.3.

Membrane stability index (MSI) was assessed to examine the petal membrane’s stability. Initially, 0.1 g of petals was weighed and uniformly cut. Subsequently, the cut petals were placed in separate test tubes, each containing 10 ml of distilled water. Two sets of samples were then subjected to measurements of electrical conductivity, with the first set measured after incubation at 40 °C for 30 min (C1) and the second set after incubation at 100 °C for 15 min (C2). The electrical conductivity measurements were conducted using EC meters (Jenway model, UK) following the methodology outlined by Almeselmani et al.49. The membrane stability index was calculated using the formula (2).

Relative Fresh Weight (RFW) and Relative Water Content (RWC) were assessed using the formula RWC = (FW − DW) / (TW − DW), where FW represents fresh weight, DW is dry weight, and TW is turgid weight. Leaf discs, obtained from 3 to 4 leaves, were promptly placed in Petri dishes to minimize evaporation. These samples were stored in the dark and weighed to determine the fresh weight (FW). Leaf pieces were then submerged in deionized water for 24 h, ensuring inhibition of physiological activity through dark incubation in the fridge. Subsequently, the turgid weight (TW) was determined, and the leaf pieces were blotted to dryness, reweighed, and subjected to drying at 70 °C for 3 days for dry weight (DW) determination, following the protocol outlined by He et al.3. The relative weight of the flowering stems was measured using a digital scale with an accuracy of 0.01 g at the initiation of the experiment, before immersion in the solutions, and periodically throughout the experiment. The relative weight of the flowering branch was calculated as a percentage using Eq. (3).

Chlorophyll fluorescence in the rose flower leaf of R. hybrida cv. Black Magic was assessed using a portable photosynthesis meter (Walz GmbH Licensing, Germany) throughout the vase life. Minimal fluorescence (F0) was measured in leaves after a 30-min dark incubation, while maximal fluorescence (Fm) was determined in the same leaf samples under full light conditions. Maximal variable fluorescence (Fv) and the maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) were then calculated based on the reported parameters50.

For rose petal antioxidative enzymes, one gram of rose petals was homogenized in 5 mL of 50 mM K–phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), supplemented with 5 mM Na–ascorbate and 0.2 mM EDTA from concentrated stocks. The homogenate samples underwent centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was used for enzyme activity measurements at 4 °C. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) was determined following the protocol by Li et al.51.

Additionally, petals (0.5 g) were collected and ground in liquid nitrogen, and the extraction process involved 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) PVP, and 0.1% (v/v) Triton x100. This extract was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were utilized for evaluating enzyme activities. Ascorbate peroxidase activity was assessed according to the protocol by Yoshimura et al.52. Peroxidase (POX) enzyme was extracted using the method by MacAdam et al.53, and its activity was measured by recording absorbance at 475 nm with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity was determined following the protocol by Nicoli et al.54.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content in rose petals was determined as per the procedure by Liu et al.55. Specifically, 0.5 g of rose petals was ground in liquid nitrogen, and the extracts were centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 25 min at 4 °C. A 100 µL aliquot of the supernatants was combined with 1 mL of xylenol solution, and after 30 min, absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) was measured as a 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactive metabolite, following the procedure described by Zhang et al.56. About 1.5 mL of the extraction was homogenized into 2.5 mL of 5% TBA made in 5% trichloroacetic acid. The reaction solution was heated at 95 °C for 15 min, cooled rapidly, and the absorbance of the supernatants was read at 532 nm.

Total phenolic compounds (TPC) were quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu method with gallic acid as the standard57. Total flavonoid compounds (TFC) were determined using a colorimetric assay following the protocol by Shin et al.58.

Carbohydrate extraction involved anthrone reagent. Fresh rose petals (0.5 g) were ground with 5 mL ethanol, and the extract was centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm. The supernatant was subjected to anthrone reagent (3 mL), and the absorbance was recorded at 625 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) according to the Fales59 method.

For measuring anthocyanins, 0.1 g of fresh rose petals was ground in 10 mL acidified methanol (1:99 v/v). The solution was centrifuged, and the supernatants were kept overnight in darkness. Absorption was read spectrophotometrically at 550 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Anthocyanin concentration was calculated using the extinction coefficient (ε = 33000 cm2 mol−1) and the formula A = εbc60.

Statistics

The experiment was designed as a factorial experiment following a completely randomized design with three replications. Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using SAS ver 9.1 software, and mean separations were executed through Duncan’s test, considering a significance level of 0.05. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was carried out using R v3.4.3 (www.r-project.org). Additionally, Pearson correlation and cluster dendrogram heat maps were generated using R foundation for statistical computing (version 4.1.2), Iran (2021).

Data availability

Availability of data and materials Correspondence and requests for the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study and materials should be addressed to Hanifeh Seyed Hajizadeh.

References

Liao, W. B., Zhang, M. L. & Yu, J. H. Role of nitric oxide in delaying senescence of cut rose flowers and its interaction with ethylene. Sci. Hort.155, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2013.03.005 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Magnesium hydride acts as a convenient hydrogen supply to prolong the vase life of cut roses by modulating nitric oxide synthesis. Postharvest Biol. Technol.177, 111526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2021.111526 (2021).

He, S., Joyce, D. C., Irving, D. E. & Faragher, J. D. Stem end blockage in cut Grevillea ‘Crimson yul-lo’inflorescences. Postharvest Biol. Technol.41(1), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.03.002 (2006).

Williamson, V. G., Faragher, J. D., Parsons, S. & Franz, P. Inhibiting the post-harvest wound response in wildflowers. Rural Industries Res. Dev. Corporation (RIRDC) Publication, (2002). (02/114).

Van Ieperen, W., Van Meeteren, U. & Nijsse, J. Embolism repair in cut flower stems: a physical approach. Postharvest Biol. Technol.25(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(01)00161-2 (2002).

Asrar, A. W. A. Effects of some preservative solutions on vase life and keeping quality of snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus L.) cut flowers. J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci.11(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2011.06.002 (2012).

Hajizadeh, H. S., Farokhzad, A. & Chelan, V. G. Using of preservative solutions to improve postharvest life of Rosa hybrid cv. Black Magic. 1801–1810. (2012).

Reid, M. S. Handling of cut flowers for export. Proflora Bull., 1–26. (2009).

Prasad, R., Bhattacharyya, A. & Nguyen, Q. D. Nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture: recent developments, challenges, and perspectives. Front. Microbiol.8, 1014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01014 (2017).

Rafi, Z. N. & Ramezanian, A. Vase life of cut rose cultivars ‘Avalanche’and ‘Fiesta’as affected by Nano-Silver and S-carvone treatments. South. Afr. J. Bot.86, 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2013.02.167 (2013).

Hajizadeh, H. S. et al. Silicon dioxide-nanoparticle nutrition mitigates salinity in gerbera by modulating ion accumulation and antioxidants. Folia Horticulturae. 33 (1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.2478/fhort-2021-0007 (2021).

Seyed Hajizadeh, H., Dadashzadeh, R., Azizi, S., Mahdavinia, G. R. & Kaya, O. Effect of Chitosan nanoparticles on quality indices, metabolites, and vase life of Rosa Hybrida Cv. Black magic. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric., 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-023-00387-7(2023).

Nakata, Y. et al. Rice blast disease and susceptibility to pests in a silicon uptake-deficient mutant lsi1 of rice. Crop Prot.27(3–5), 865–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2007.08.016 (2008).

Savvas, D. & Ntatsi, G. Biostimulant activity of silicon in horticulture. Sci. Hort.196, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.010 (2015).

Geerdink, G. M. et al. Pre-harvest silicon treatment improves quality of cut rose stems and maintains postharvest vase life. J. Plant Nutr.43(10), 1418–1426. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2020.1730894 (2020).

Turakainen, M. Selenium and its effects on growth, yield and tuber quality in potato. (2007).

Golubkina, N. A. et al. Intersexual differences in plant growth, yield, mineral composition and antioxidants of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) as affected by selenium form. Sci. Hort.225, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.07.001 (2017).

Golubkina, N. et al. Foliar application of selenium under nano silicon on Artemisia annua: effects on yield, antioxidant status, essential oil, artemisinin content and mineral composition. Horticulturae. 8 (7), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070597( (2022).

Chi SunLin, C. S., Xu WeiHong, X. W., Liu Jun, L. J. & WeiZhong, W. W. W., & Xiong ZhiTing, X. Z. Effect of exogenous selenium on activities of antioxidant enzymes, cadmium accumulation and chemical forms of cadmium in tomatoes. (2017).

Pereira, A. S. et al. Selenium and silicon reduce cadmium uptake and mitigate cadmium toxicity in Pfaffia Glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen plants by activation antioxidant enzyme system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.25, 18548–18558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-2005-3 (2018).

Lu, N., Wu, L. & Shi, M. Selenium enhances the vase life of Lilium longiflorum cut flower by regulating postharvest physiological characteristics. Sci. Hort.264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109172 (2020).

Wu, Z., Liu, S., Zhao, J., Wang, F., Du, Y., Zou, S., … Huang, Y. Comparative responses to silicon and selenium in relation to antioxidant enzyme system and the glutathione-ascorbate cycle in flowering Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp. chinensis var. utilis) under cadmium stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 133, 1–11.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.09.005 (2017).

Rastogi, A., Tripathi, D. K., Yadav, S., Chauhan, D. K., Živčák, M., Ghorbanpour, M., ... & Brestic, M. (2019). Application of silicon nanoparticles in agriculture. 3 Biotech, 9, 1-11.

Helaly, M. N., El-Metwally, M. A., El-Hoseiny, H., Omar, S. A. & El-Sheery, N. I. Effect of nanoparticles on biological contamination of’in vitro’cultures and organogenic regeneration of banana. Aust. J. Crop Sci.8(4), 612–624 (2014).

Elsheery, N. I., Helaly, M. N., El-Hoseiny, H. M. & Alam-Eldein, S. M. Zinc oxide and silicone nanoparticles to improve the resistance mechanism and annual productivity of salt-stressed mango trees. Agronomy. 10 (4), 558 (2020).

Tognon, G. B., Sanmartín, C., Alcolea, V., Cuquel, F. L., & Goicoechea, N. Mycorrhizal inoculation and/or selenium application affect post-harvest performance of snapdragon flowers. Plant growth regulation, 78, 389-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-015-0100-8 (2016).

Hajizadeh, H. et al. Identification and characterization of genes differentially displayed in Rosa Hybrida petals during flower senescence. Sci. Hort.128(3), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2011.01.026 (2011).

Ahmadi-Majd, M., Mousavi-Fard, S., Nejad, R. & Fanourakis, D. Nano-Selenium in the holding solution promotes rose and carnation vase life by improving both water relations and antioxidant status. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol.98(2), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2022.2125449 (2023).

Kamiab, F., Shahmoradzadeh Fahreji, S., & Zamani Bahramabadi, E. Antimicrobial and physiological effects of silver and silicon nanoparticles on vase life of lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflora cv. Echo) flowers. International Journal of Horticultural Science and Technology, 4(1), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijhst.2017.228657.180 (2017).

Tognon, G. B., Sanmartín, C., Alcolea, V., Cuquel, F. L. & Goicoechea, N. Mycorrhizal inoculation and/or selenium application affect post-harvest performance of snapdragon flowers. Plant. Growth Regul.78, 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-015-0100-8 (2016).

Zheng, M. & Guo, Y. Effects of neodymium on the vase life and physiological characteristics of Lilium Casa Blanca petals. Sci. Hort.256, 108553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108553 (2019).

Handa, N. et al. Selenium ameliorates chromium toxicity through modifications in pigment system, antioxidative capacity, osmotic system, and metal chelators in Brassica juncea seedlings. South. Afr. J. Bot.119, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2018.08.003 (2018).

Kamiab, F., Fahreji, S. & Zamani Bahramabadi, E. Antimicrobial and physiological effects of silver and silicon nanoparticles on vase life of lisianthus (Eustoma Grandiflora Cv. Echo) flowers. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol.4(1), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijhst.2017.228657.180 (2017).

Bahabadi, S. E. et al. Time-course changes in fungal elicitor-induced lignan synthesis and expression of the relevant genes in cell cultures of Linum album. J. Plant Physiol.169(5), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2011.12.006 (2012).

Song, J., Yang, J. & Jeong, B. R. Synergistic effects of Silicon and Preservative on promoting Postharvest Performance of Cut flowers of Peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall). Int. J. Mol. Sci.23(21), 13211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113211( (2022).

Gitelson, A. A., Gritz, Y. & Merzlyak, M. N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol.160(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1078/0176-1617-00887 (2003).

Dwivedi, S. K., Arora, A., Singh, V. P., Sairam, R., & Bhattacharya, R. C. Effect of sodium nitroprusside on differential activity of antioxidants and expression of SAGs in relation to vase life of gladiolus cut flowers. Scientia Horticulturae, 210, 158-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.07.024 (2016).

Sali, A., Zeka, D., Fetahu, S., Rusinovci, I. & Kaul, H. P. Selenium supply affects chlorophyll concentration and biomass production of maize (L). Die Bodenkultur: J. Land. Manage. Food Environ.69(4), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.2478/boku-2018-0021 (2018).

Mwangi, M., & Bhattacharjee, S. K. Influence of pulsing and dry cool storage on postharvest life and quality of ‘Noblesse’cut roses. Journal of Ornamental Horticulture, 6(2), 126–129. (2003).

Madhumitha, G. & Saral, A. M. Free radical scavenging assay of Thevetia neriifolia leaf extracts. 21(3):2468–2470. (2009).

Dwivedi, S. K., Arora, A., Singh, V. P., Sairam, R. & Bhattacharya, R. C. Effect of sodium nitroprusside on differential activity of antioxidants and expression of SAGs in relation to vase life of gladiolus cut flowers. Sci. Hort.210, 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.07.024 (2016).

El-Serafy, R. S. Silica nanoparticles enhances physio-biochemical characters and Postharvest Quality of L. Cut Flowers. J. Hortic. Res.27(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.2478/johr-2019-0006 (2019).

Mwangi, M. & Bhattacharjee, S. K. Influence of pulsing and dry cool storage on postharvest life and quality of ‘Noblesse’cut roses. J. Ornam. Hortic.6(2), 126–129 (2003).

Seyed Hajizadeh, H., Mostofi, Y., Razavi, K., Zamani, Z. & Mousavi, A. Gene expression in opening and senescing petals of rose (Rosa Hybrida L). Acta Physiol. Plant., 36, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-013-1400-0(2014).

Hajizadeh, H. S. The study of freesia (Freesia spp.) cut flowers quality in relation with nano silver in preservative solutions. In III International Conference on Quality Management in Supply Chains of Ornamentals 1131. 1–10. (2015), May.

Triticum aestivum L.) grains. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 70(41), 13431–13444. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c04868 (2022).

Rezai, S., Nikbakht, A., Zarei, H., & Sabzalian, M. R. (2023). Physiological, biochemical, and postharvest characteristics of two cut rose cultivars are regulated by various supplemental light sources. Scientia Horticulturae313 111934.

Jiang, Y. et al. Cu/ZnSOD involved in tolerance to dehydration in cut rose (Rosa Hybrida). Postharvest Biol. Technol.100, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.10.005 (2015).

Almeselmani, M. et al. Effect of drought on different physiological characters and yield component in different varieties of Syrian durum wheat. J. Agric. Sci.3(3), 127 (2011).

Jia, M., Li, D., Colombo, R., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Cheng, T., … Zhang, C. Quantifying chlorophyll fluorescence parameters from hyperspectral reflectance at the leaf scale under various nitrogen treatment regimes in winter wheat. Remote Sensing, 11(23), 2838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11232838(2019).

Li, J. T., Qiu, Z. B., Zhang, X. W. & Wang, L. S. Exogenous hydrogen peroxide can enhance tolerance of wheat seedlings to salt stress. Acta Physiol. Plant.33, 835–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-010-0608-5 (2011).

Yoshimura, K., Yabuta, Y., Ishikawa, T. & Shigeoka, S. Expression of spinach ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes in response to oxidative stresses. Plant Physiol.123(1), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.123.1.223 (2000).

MacAdam, J. W., Nelson, C. J. & Sharp, R. E. Peroxidase activity in the leaf elongation zone of tall fescue: I. spatial distribution of ionically bound peroxidase activity in genotypes differing in length of the elongation zone. Plant Physiol.99(3), 872–878. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.99.3.872 (1992).

Nicoli, M. C., ELIZALDE, B. E., PITOTTI, A. & LERICI, C. R. Effect of sugars and maillard reaction products on polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase activity in food. J. Food Biochem.15(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4514.1991.tb00153.x (1991).

Liu, Y. H., Offler, C. E. & Ruan, Y. L. A simple, rapid, and reliable protocol to localize hydrogen peroxide in large plant organs by DAB-mediated tissue printing. Front. Plant Sci.5, 745. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00745 (2014).

Zhang, Z. B. et al. On evolution and perspectives of bio-watersaving. Colloids Surf., B. 55 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.10.036 (2007).

Slinkard, K. & Singleton, V. L. Total phenol analysis: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Viticult.28(1), 49–55 (1977).

Shin, Y., Liu, R. H., Nock, J. F., Holliday, D. & Watkins, C. B. Temperature and relative humidity effects on quality, total ascorbic acid, phenolics and flavonoid concentrations, and antioxidant activity of strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol.45(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.03.007 (2007).

Fales, F. The assimilation and degradation of carbohydrates by yeast cells. J. Biol. Chem.193(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52433-4 (1951).

Wagner, G. J. Content and vacuole/extravacuole distribution of neutral sugars, free amino acids, and anthocyanin in protoplasts. Plant Physiol.64(1), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.64.1.88 (1979).

Acknowledgements

The present study was carried out by the use of facilities and materials at the University of Maragheh and the paper is published as the part of a MSc. Student research at University of Maragheh, research affairs office.

Funding

The current research has received no funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S.H. conceived and designed the experiments; S.E. performed the experiments; S.M.Z. and H.F. analyzed the data; H.S.H. and O. K. wrote and proof the final paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Plant permission statement

We obtained permission for collection of plant material used in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

SeyedHajizadeh, H., Esmaili, S., Zahedi, S.M. et al. Silicon dioxide and selenium nanoparticles enhance vase life and physiological quality in black magic roses. Sci Rep 14, 22848 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73443-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73443-3