Abstract

The use of supramolecular assemblies in pharmaceuticals has garnered significant interest. Recent studies have shown that the activities of antibacterial agents can be enhanced through complexation with cyclic oligomers and metal ions. Notably, these complexes sometimes possess greater therapeutic properties than the parent drugs. To develop microbiologically potent supramolecular drugs, the complexation of macrocyclic hosts with fluoroquinolone (FQ) antibiotics was investigated. FQs are a successful family of antibiotics that target the bacterial enzymes DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV, leading to bacterial cell death through the inhibition of DNA synthesis. However, antibiotic resistance resulting from the repeated use of FQs over time has limited their effectiveness against resistant pathogens. To overcome this issue, the encapsulation of FQs in polyphenolic macrocycles was investigated. This study highlights resorcinarene, a polyphenolic host with antibacterial properties, and its ability to chemically interact with FQs. The inclusion complexation process was analyzed using NMR and FTIR techniques. The binding constants determined by 1H-NMR titration revealed that levofloxacin forms more stable complexes with resorcinarene than with β-cyclodextrin, which aligned with MD simulations. Assessment of the geometric characteristics of the inclusion complexes using 2D NMR analysis confirmed that different moieties of various FQs can fit into a single host cavity and improve activity against gram-negative bacteria. Overall, these findings suggest that encapsulation in polyphenolic macrocycles is a promising strategy for utilizing FQs against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotics have played a vital role in healthcare since the 1940s1, safeguarding vulnerable patients, especially during surgeries2. However, the “golden age” of antibiotic discovery3 from natural microorganisms (1940–1962) was followed by an “innovation gap” due to antibiotic-resistant strains4,5. Efforts to modify existing compounds have faced obstacles, such as high costs and rapid resistance development. The latter issue is exemplified by the appearance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) following the introduction of methicillin-based antibiotics6. The overuse of antibiotics7,8, driven by factors including rising incomes and increased demand for animal proteins9, has exacerbated this problem. Despite steady growth in the antibiotic market, developing new antibiotics remains challenging, with a low success rate and long development period. Typically, combating resistance involves neutralizing bacterial defense mechanisms through structural modifications or enhancing existing drug efficacy using carriers such as liposomes10, nanoparticles11, and macrocycles12,13,14,15,16.

Macrocycles are cyclic molecules that have distinctive sizes, shapes, and repeating units that contribute to unique guest binding and self-assembling properties. Crown ethers are known for their selective cation binding17. Cyclodextrins feature hydrophobic cavities18, while calixarenes have modifiable cup-shaped structures19,20. Cucurbiturils possess rigid, high-affinity binding cavities21, and pillararenes are characterized by symmetric cylindrical cavities22,23,24. Each of these macrocycles offers properties that make them versatile carriers for pharmaceutical applications. Among macrocycles, cyclodextrins stand out as naturally derived and safe compounds. Thus, cyclodextrins are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to enhance the solubility and stability of various drugs, such as itraconazole25 and rifampicin26. As macrocyclic supramolecular hosts, calixarenes27,28 and closely related resorcinarenes29,30 possess concave binding cavities and exhibit strong affinities for a wide range of guest molecules, including cations (alkali and alkaline earth metals, transition metals, and ammonium ions), anions, and small organic compounds31,32. Resorcinarenes30,33, cyclic polyphenols 34, are remarkably adaptable, as they can incorporate distinct substituents in the electron-rich upper-rim groups and lower-rim alkyl chains35. In addition, resorcinarenes bearing sulfonate groups have anionic properties, resulting in enhanced water solubility, and an electron-rich hydrophobic interior cavity36 that can interact with various guests through hydrogen bonding or π-interactions34. Because of their exceptional adaptability and high affinity for hydrogen bonding, resorcin[4]arenes are promising candidates for host–guest chemistry. Notably, water-soluble anionic and cationic resorcinarene receptors can disrupt the peptide aggregation associated with cataracts37, exemplifying the potential of these compounds for therapeutic applications38,39. Moreover, resorcinol, the building block of resorcinarene macrocycles, acts as a coformer to enhance the solubility and dissolution rate of norfloxacin (NOR) in pharmaceutical cocrystals40. Owing to its versatile nature, with two strong hydrogen bond donors, resorcinol is also effective in stabilizing vitamin D341 and forming cocrystals with compounds such as curcumin42 and ciprofloxacin (CIPRO)43.

Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are a rapidly expanding category of antibiotics44 that inhibit bacterial enzymes crucial for DNA replication, making them effective against various bacterial infections45,46. However, the use of FQs has been limited by severe adverse reactions and antibiotic resistance47,48. Active efforts have been focused on synthesizing various derivatives and assessing their efficacy against diverse microbial infections. Breakthroughs in the development of new generations of FQs resulted in significant enhancements in potency, range of action, and physical characteristics49. The exploration of structure–activity relationships provided valuable insights into the key features responsible for antibiotic effectiveness, such as the presence of a fluorine atom and the 1-alkyl-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-quinoline-3-carboxylic acid structure50. In addition, specific functional groups, such as fluoro and piperazinyl groups, are believed to play vital roles in expanding the spectrum of activity and improving antipseudomonal properties50,51. Furthermore, chemical modifications at piperazinyl have been explored to regulate the pharmacokinetic properties and enhance the cell permeability of these promising antibacterial agents52. Notably, β-cyclodextrin (β-CD)53 and cucurbituril54 have been demonstrated to enhance the activity of FQs and other antibacterial drugs such as doxycycline55. These ongoing efforts are paving the way for more efficient and versatile FQ antibiotics.

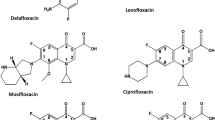

Herein, wee compared the ability of sulfonato-C-methylresorcin[4]arene (SRsC1) to form complexes with FQs (Fig. 1) to that of widely used β-CD. SRsC1 was chosen because it contains repeating phenolic units. and Polyphenols56,57,58 are known to disrupt bacterial membranes, contributing to antibacterial activity. Additionally, the acidic hydroxyl groups in non-sulfonated resorcinarenes interact with the basic amine groups of FQs through acid–base reactions29. Interestingly, the sulfonato group provides additional solubility and interaction sites. In this study, we focused on how binding stability determines the strength and specificity of the interaction between the host and guest molecules, The orientation and positioning of functional groups on both molecules can impact both stability and reactivity, which can influence bioavailability and efficacy. Inspired by the favorable characteristics of resorcinarene, we focused on developing resorcinarene-encapsulated FQ antibiotics. These compounds were tested against bacterial strains with the aim of enhancing antibiotic potency and in turn altering the clinical behavior against resistant bacteria. Furthermore, correlation of the partitioning behavior of these derivatives between octanol and buffer solutions (pH 7.4) with their antibacterial activities was explored to identify which parameters are crucial for successful host–guest complexation.

Results and discussion

Solution-state study of FQ guests with cyclic macromolecules

Complex stoichiometry and association constant

Stoichiometry is crucial factor for the in-depth characterization of host–guest interactions. Therefore, the continuous variation method or Job’s method59 was used to determine the stoichiometry of the inclusion complexes between the FQ guests and SRsC1 or β-CD. To construct Job plots, 1H-NMR titration was performed (Fig. S1). The chemical shifts (δ) were measured at different guest/host concentration ratios while keeping the total concentration ([G] + [H]) constant. The calculated factors (∆δ × XG, i.e., the difference between the chemical shifts of the host–guest mixture (δG-H) and guest (δG) multiplied by the molar ratio of the guest (XG)) were plotted against XG. All the titration curves showed a maximum at XG = 0.5 for all the monitored nuclei (Fig. S2), suggesting a 1:1 complex stoichiometry. The chemical shifts (δ) of selected protons for the FQ guests and macrocyclic hosts in the free and complexed (equimolar) states are summarized in Table 1. A positive sign for Δδ indicates a downfield shift, whereas a negative sign indicates an upfield shift. We observed no new peaks in the 1H-NMR spectra of the inclusion complexes (Fig. S3 and S4). Thus, inclusion of the FQs in the macrocycles is a fast exchange process that occurs on the NMR timescale60.

Levofloxacin (LEVO) with SRsC1/β-CD: In the presence of SRsC1 or β-CD (Fig. S3a and b), the piperazine protons (H2LEVO and H4LEVO) of LEVO shifted significantly upfield, suggesting their involvement in hydrophobic interactions with the interior of the host cavity. In particular, the shift of H2LEVO could be attributed to magnetic anisotropy effects when located near the aromatic ring of SRsC1, which is rich in π-electrons61. Other aromatic protons (H8LEVO and H7LEVO) shifted gradually downfield, mainly due to variations in the polarity of their microenvironment when LEVO was within the host cavity. These changes also indicated a shielding effect resulting from the host–guest interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions34. Moreover, the downfield shift of HbSRsC1 of SRsC1 was attributed to a deshielding effect caused by π-H bonding with the piperazine moiety of LEVO. Interestingly, no proton shifts were observed for β-CD in the presence of LEVO.

SRsC1 with CIPRO/NOR: The aromatic proton of SRsC1 (HbSRsC1) shifted significantly downfield in the presence of both NOR and CIPRO, which are structurally related. Interestingly, the aromatic protons of NOR (H5NOR and H5NOR) and CIPRO (H6CIPRO and H7CIPRO) also shifted downfield (Fig. S4a and b). This strong deshielding effect was due to π–π bonding between the host and guest. In contrast, no shifts were observed for the piperazine protons of NOR and CIPRO, suggesting that the aromatic ring system of the guest plays a major role in the inclusion process. Furthermore, the strong upfield shift of the bridging proton of SRsC1 (HdSRsC1) in the presence of NOR indicated shielding by the methyl protons of NOR (H10NOR, Fig. S4b). The titration data were also used to calculate the association constant and stoichiometry for each FQ guest with the macrocycles. The Ka and N values of various host–guest complexes are given in Table 2.

The change in the chemical shift (Δδ) was plotted as a function of the host (SRsC1 or β-CD) concentration for each FQ guest (LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR), and global analysis was applied to determine the host/guest affinity (Fig. 2). LEVO was found to form a tighter complex with SRsC1 than with β-CD. Among the FQ guests, SRsC1 exhibited the strongest binding with CIPRO. In each case, except for β-CD–LEVO, the binding stoichiometry was 1:1, consistent with the results of the continuous variation method. However, as Job plots have some limitations62 for higher stoichiometries, the formation of a 2:1 β-CD–LEVO complex is likely. Notably, the association constant values obtained for the complexes are generally considered suitable for improving the bioavailability or therapeutic efficacy of guests63.

Intermolecular interactions between hosts and FQ guests

Diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY). The intrinsic diffusion coefficients (D) of molecules, as determined using DOSY experiments, can be used to characterize intermolecular interactions in solution. Table 3 shows the D values of the free host and guest molecules as well as those of the host–guest complexes at equimolar ratios. A slowly diffusing molecule, indicated by a lower D value, is typically heavier. The guests had higher D values than the host molecules, consistent with the FQs being smaller than the macrocycles64. Moreover, the FQ–macrocycle mixtures diffused more slowly than the free components, indicating an increase in molecular size due to complexation. However, the D value of SRsC1 was relatively unaffected by the presence of CIPRO or NOR owing to the small relative mass change upon complexation of the macrocycle with these structurally related guests. Nonetheless, the D values of both CIPRO and NOR decreased in the presence of SRsC1 (Table 3 and Fig. S5c, d), providing evidence that these guests are included in the SRsC1 cavity and undergo slow diffusion. Similarly, the D value of LEVO decreased in the presence of SRsC1 or β-CD (Table 3 and Fig. S5a, b), indicating that this guest diffuses slowly because it is included in the cavities of both macrocycles.

2D NOESY. Nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) cross-peaks between the protons of the guest and macrocycle indicate that the protons are near each other in space (< 4 Å)65. As revealed by the full 2D NOE spectra in Fig. 3a, intermolecular cross-peaks occurred between the protons of the FQs and SRsC1. Strong intermolecular cross-peaks were present between the Hb and Hd protons of SRsC1 and the H2 proton of LEVO, although that with the bridging Hd proton of SRsC1 was weaker. These results indicate that the piperazine moiety of LEVO enters the SRsC1 cavity while the aromatic and pyrido rings remain outside. In contrast, β-CD only exhibited intramolecular cross-peaks, with no intermolecular cross-peaks with LEVO (Fig. S6). This behavior suggests that β-CD forms dimers that encapsulate LEVO, in agreement with the 1H-NMR results66.

Both CIPRO and NOR exhibited two significant sets of intermolecular cross-peaks (Fig. 3b and c), suggesting that both guests interact with SRsC1 in a similar manner. Strong cross-peaks were observed between the piperazine protons (H2, H3, and H8 of NOR; H3 and H4 of CIPRO) and the aromatic protons (Hb) of the host, indicating close interactions between these groups. In addition, we observed proximity between the aliphatic protons of the guests (H1, H4, and H10 of CIPRO; H1 of NOR) and the host protons (Hb and Hd). These results suggest complexation and the formation of specific interactions between SRsC1 and CIPRO or NOR. Notably, no cross-peaks were observed for the aromatic protons of the guests CIPRO and NOR, consistent with the 1D 1H-NMR results. This finding may indicate a different mode of interaction or less direct involvement in complexation.

Solid-state study of FQ guests with cyclic macromolecules via FTIR spectroscopy

We investigated the IR absorption peaks of different host–guest systems to gain insights into the interactions in the inclusion complexes. Significant differences were observed between the FTIR spectra of SRsC1 and freeze-dried SRsC1–LEVO (1:1) (Fig. 4a). The disappearance of the peaks at 3233.6 and 2802.1 cm−1, corresponding to N–H and C–H stretching (aliphatic methyl group) in LEVO, respectively, indicates the formation of a host–guest complex, with the hydroxy (–OH) group of SRsC1 hydrogen bonding to a partially negatively charged tertiary nitrogen of LEVO67. Furthermore, the O–H stretching frequency of neat SRsC1 (3387.6 cm−1) was red-shifted to 3406 cm−1 upon interaction with LEVO, suggesting the presence of hydrogen bonding68,69 in the SRsC1–LEVO complex.

The disappearance of the C = O peak of LEVO at 1719.5 cm−1 in the SRsC1–LEVO mixture further confirms the involvement of the carbonyl group in complexation, consistent with the solution-state results. In the presence of β-CD, the absorption peak of LEVO at 3233.6 cm−1, corresponding to N–H stretching, disappeared (Fig. 4b), indicating the formation of a complex. In addition, the β-CD peak at 3274.6 cm−1 (O–H stretching) decreased in intensity and shifted to a higher wavenumber, suggesting the formation of an inclusion complexation with LEVO. Furthermore, the bands at 1642.7 and 1719.5 cm−1 (C = O stretching) of both β-CD and LEVO disappeared for the β-CD-LEVO (1:1) complex, and decreases in intensity and masking were observed in the fingerprint region.

For freeze-dried SRsC1–NOR (1:1), the peak corresponding to the N–H stretching of the piperazinyl group in NOR was red-shifted to 3405.8 cm−1 (Fig. 4c). This shift likely resulted from proton exchange via hydrogen bonding with SRsC1, leading to an overlap between the NOR peak at 3339.1 cm−1 and the SRsC1 peak at 3387.6 cm−1. A similar shift was observed for freeze-dried SRsC1–CIPRO (1:1) (Fig. 4d). These results provide valuable evidence for the formation of inclusion complexes, as changes in the shape, position, and intensity of the IR absorption peaks of guest or host molecules can be indicative of complex formation70. Unlike those of the inclusion complexes, the FTIR spectra of the physical mixtures exhibited peaks corresponding to the individual hosts and FQs (Fig. 4), consistent with previous findings71. Although the spectra of the physical mixtures appeared nearly identical to those of the host and FQ drugs alone, these results suggest that weak interactions occur in the physical mixtures.

Computational results: Classical MD simulations were utilized to probe possible interactions between hosts (SRsC1 and β-CD) guests (FQs). To quantify the effect of host–guest interactions on the host geometry, we monitored the lower-rim, upper-rim, and mid radii of the hosts and the center of mass (COM) distance between the host and guest (Tables S1 and S2). Host–guest interactions had minimal effects on the SRsC1 or β-CD framework, which maintained their original conformations. However, the sulfonato groups of SRsC1 did vary interaction with a guest molecule. Production runs were carried out for SRsC1 with the piperazinyl group of the guest oriented within the host cavity and with the guest at least 10 Å above the host. When the piperazinyl group was oriented within the host cavity, the guest stayed in the cavity, except in the case of SRsC1–NOR, (Fig. 5a, c). Although sulfonato group rotation was relatively unhindered, the sulfonato groups of SRsC1 tended to interact with the guest. For this initial SRsC1–NOR structure, a Na+ ion came into proximity and interacted with SRsC1 during NPT equilibration. Consequently, the SRsC1–NOR interaction was disrupted, leading to NOR interacting with the top rim of SRsC1. For all the host–guest combinations with the guest initially oriented above the host, the guest moved closer and began to interact with the side of the host or the upper rim (Fig. 5b, d). Interestingly, in the SRsC1–NOR simulation, NOR began to move toward SRsC1 (around 4 ns in Fig. 5d) at the same time as Na+ moved toward SRsC1. At 4–13 ns, the Na+ ion interacted with 2–3 of the sulfonato groups , while NOR started to interact with SRsC1 at ~7 ns. As NOR began to interact with the top rim of SRsC1, the Na+ ion was released.

Distances between the COMhost and COMguest. The data for SRsC1–LEVO and β-CD–LEVO when LEVO is initially within SRsC1/β-CD and above SRsC1/β-CD are shown in (a) and (b), respectively. The data for SRsC1–CIPRO and SRsC1–NOR when CIPRO/NOR is initially within SRsC1 and above SRsC1 are shown in (c) and (d), respectively.

The interaction of SRsC1–NOR with Na+ ions could be key to designing more effective drug delivery systems by influencing drug stability, release rates, and membrane penetration. Na+ ions could enable controlled, targeted delivery via ion-triggered release to directs the drug to specific tissues or cells where Na+ levels vary and promote competitive binding in specific environments. These factors enhance therapeutic precision and minimize side effects, offering valuable insights for optimizing drug efficacy and safety72,73. An additional set of production runs was perfomed in which the guest interacted with the host cavity and the number of solvent molecules was constant. For all host–guest combinaations, the guest interacted with the host throughout the production run. The host–guest distance resembled that in Fig. 5a, and complete data can be found in the supporting information. The SRsC1 complexes exhibited stronger interactions due to the sulfonato group interacting with the guest. For LEVO (Fig. 6a) and NOR, the piperazine group stayed within the cavity for the entire simulation. However, the most favorable binding enthalpy was observed for SRsC1–CIPRO (Fig. 6b; Table 4), in which the cyclopropyl group of CIPRO remained within the SRsC1 cavity. This results is indicative of hydrogen bonding interactions between the NH group of CIPRO and a neighboring SO3 group of SRsC1 as well as interactions between the SO3 groups and the COOH end of CIPRO. Regardless of the solvent–host/guest–ion system investigated, host–guest interactions were observed. Thus, complex formation was favorable despite the variation in interaction sites. For the guest interacting with the host cavity and its functional groups, the binding enthalpy trend agreed with the experimentally obtained Ka values, which implies that the enthalpic contribution to ΔG is greater than the entropic contribution.

Antibacterial activity

Activities of FQ complexes against gram-negative and positive bacteria. The antibacterial effectiveness of complexed FQs against gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) was compared with that of uncomplexed FQs. For this purpose, a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay was conducted at various concentrations via serial dilution from 2× MIC on 96-well plates. The percentage growth inhibition of bacterial cells treated with complexed and uncomplexed FQs was determined by comparison with the untreated control (Fig. S8a, b & c). The concentrations tested for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus varied based on the MIC of individual antibiotics. Notably, the FQs exhibited a growth inhibitory effect on P. aeruginosa at 2- or 3-times lower concentrations than required for S. aureus.

All three FQs (CIPRO, NOR, and LEVO) and their complexes with the polyphenolic macrocycle SRsC1 demonstrated 90% inhibition of bacterial cells at higher concentrations. However, the inhibitory effect against both bacterial strains decreased at lower concentrations. The percent inhibition curves for the free and complexed FQs exhibited similar behavior. However, at specific concentrations, the complexed FQs displayed slightly lower inhibition of both bacteria. The MIC assays of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in Fig. S8a revealed that exposure to 12 µg/mL of SRsC1–CIPRO or CIPRO killed 98.30 ± 0.26% of S. aureus, whereas 4 µg/mL was required to kill 100.67 ± 0.39% of P. aeruginosa. Similarly, SRsC1–NOR and NOR both demonstrated inhibitory effects of 97.90 ± 0.38% aginst S. aureus at 128 µg/mL and 100.43 ± 0.17% against P. aeruginosa at 40 µg/mL (Fig. S8b). We also evaluated LEVO complexed with β-CD (Fig. S8c) to assess the impact of the macrocycle on biological activity. β-CD–LEVO exhibited a 78.08 ± 3.66% inhibitory effect against S. aureus and a 54.84 ± 6.02% inhibitory effect against P. aeruginosa at 4 and 8 µg/mL, respectively, representing an approximately 2-fold decrease compared to the inhibitory effects of SRsC1–LEVO (Fig. S8c).

Although the complexed forms of NOR, CIPRO, and LEVO did not exhibit significant improvements compared to their free forms, they each hada 1:1 stoichiometry with the host. Consequently, the measured quantity of antibiotic within the complex was reduced by half compared to the free antibiotic dose. This deliberate configuration ensured that the efficacy of each FQ (CIPRO, NOR, and LEVO) remained robust in the presence of SRsC1. The sustained antimicrobial effectiveness at a reduced quantity underscores the efficacy of the 1:1 stoichiometric complexation strategy employed in this study.

Effect of FQ complexes on sensitive and resistant strains of P. aeruginosa. We also compared the inhibitory activitis of the FQ complexes with those of the free antibiotics against sensitive (S) and resistant (R) strains of P. aeruginosa. Both complexed and free FQs exhibited lower inhibitory activities against resistant strains. However, a 2-fold increase in inhibitory effect was observed for SRsC1–CIPRO (0.09 ± 0.01 absorbance at 600 nm) compared to free CIPRO (0.19 ± 0.07 absorbance at 600 nm) at 4 µg/mL (Fig. S9a). As shown in Fig. 7a, SRsC1–CIPRO exhibited significant inhibitory effects at 4 and 0.5 µg/mL. The enhanced activity of the SRsC1–CIPRO complex is likely due to the orientation of CIPRO within the macrocycle, with the piperazine moiety extending outside the cavity. This orientation may facilitate bacterial membrane penetration through electrostatic interactions with anionic groups on the bacterial surface, potentially bypassing traditional porin channels and enabling broader antibiotic uptake56,74,75. However, it is important to clarify whether the bacteriostatic activity of CIPRO is sustained when complexed with SRsC1 or only triggered upon release from the complex. The mechanism of release, which could involve environmental triggers such as pH changes or interactions with bacterial enzymes, remains unclear, as does the specific interaction of the complex with FQs in resistant bacteria. Further investigation is needed to determine the exact pathways by which these complexes exert antibacterial effects. In contrast, NOR, an analog of CIPRO with a slightly different side chain, maintained inhibitory effects against both strains in its free and complexed forms (Fig. S9b). Although complexed NOR was effective at lower concentrations (2.25 and 4.50 µg/mL) against the resistant strain of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7b), the impact was nonsignificant. When comparing the complexes of LEVO with two different macrocycles (SRsC1 and β-CD), we observed that SRSC1–LEVO performed better against both the sensitive and resistant strains (Fig. S9c, d). Moreover, the activities of SRsC1–-LEVO and free LEVO against resistant bacteria remained consistent throughout the entire range of tested concentrations (Fig. S9c). In contrast, β-CD–LEVO exhibited greater inhibition of the resistant strain than the sensitive strain at higher concentrations (8–2 µg/mL), but was not comparable to LEVO itself. Despite the inherent resistance of these strains, the SRsC1–LEVO complex exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect than β-CD–LEVO, as shown in Fig. 7c and d. At certain concentrations in Fig. 7, the FQs complexed with SRsC1 were more effective against resistant bacteria than the free FQs were against sensitive strains. Comparable inhibitory effects against resistant bacteria were predominant at lower concentrations (4–0.5 µg/mL, 2.25–4.5 µg/mL, and 0.5–2.0 µg/mL) for SRsC1-complexed CIPRO, NOR, and LEVO than for the individual FQs. However, at subinhibitory concentrations, increases in concentration did not always increase the growth inhibition of sensitive strains. This behavior may be due to the subinhibitory effects of the antibacterial agent, which do not completely prevent bacterial growth. Subinhibitory effects occur when bacteria are exposed to concentrations of an antibacterial agent below the MIC or altered by gene expression or adaptive responses76,77.

Effect of complexed FQ antibiotics against resistant (R) strains of P. aeruginosa: (a) CIPRO, SRsC1–CIPRO, (b) NOR, SRsC1–NOR, (c) LEVO, SRsC1–LEVO, and (d) LEVO, β-CD–LEVO. Values represent the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Student’s paired two-tailed t-test, * statistically significant value with p < 0.05 for macrocycle–FQ complexes vs. FQs (control).

Correlation between partition coefficient and log MIC. The experimental partition coefficients between octanol and phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (Ko/w), expressed as log P, of the free FQs and their complexes with macrocyclic hosts are listed in Table 5. The experimental log P values, which are similar to reported values, indicate that the free FQs are hydrophilic in nature. LEVO was least hydrophilic (log P = −0.41), followed by CIPRO and NOR (log P= −0.99 and −2.07). This hydrophilicity is due to the zwitterionic nature of the FQs at physiological pH, which is close to the isoelectric point (pH 7.0). The neutral species of similar compounds tend to be more lipophilic than the zwitterionic species78,79, and the partitioning of quinolones is presumed to follow this trend. Unsurprisingly, despite having aromatic groups, polyphenolic macrocycle SRsC1 exhibited a negative log P value (−0.99), which indicates partitioning behavior in the aqueous phase similar to that of CIPRO. Furthermore, the macrocyclic complexes of the FQs (SRsC1–LEVO, log P = 0.34; SRsC1–NOR, log P = 0.51; and SRsC1–CIPRO, log P = 0.40) were less hydrophilic than the free FQs. The increased partition coefficients could result from an increase in hydrophobicity of the FQs after complexation with SRsC180. Similarly, β-CD slightly decreased the hydrophilicity of LEVO, with log P increasing from −0.41 to −0.02.

To further understand the influence of the partition coefficient on the antibacterial activity of FQ complexes, the parabolic curve correlation was evaluated49. The parabolic relationship between the antibacterial activities (log MIC) and experimental log P was fitted by applying the following general regression equation.

where Y = log MIC; log X = log P; and a, b and c are constants.

The parabolic curve fitting between log MIC and log P was not correlated for gram-positive (S. aureus) and resistant gram-negative (P. aeruginosa) bacteria (r2 = 0.182 and 0.363) Thus, the lipophilicity of the molecule is not the only factor determining penetration into the bacterial membrane and hence the activity. Indeed, other factors such as molecular bulkiness and the difference in affinity between complexed and free FQs also play important roles in bacterial membrane penetration81,82.

This correlation was stronger in the case of sensitive gram-negative P. aeruginosa (r2 = 0.605), as shown in Fig. S10. These findings are consistent with a previous study on the hydrophobicity of NOR derivatives, which revealed good correlation between MIC and hydrophobicity for sensitive strains of P. aeruginosa49. Molecular mass and bulkiness have been reported to hinder the penetration of FQs into gram-negative bacteria through porin channels, although hydrophobic molecules may enter via the lipopolysaccharide layer or across the lipid bilayer83,84. Optimizing the partition coefficient is key to improving both drug delivery and therapeutic effectiveness, especially when targeting bacterial membranes. A properly balanced partition coefficient ensures that the solubility and permeability of an antibiotic is suitable for efficiently penetrating bacterial cells and reaching its intended site of action. This knowledge also enables the strategic modification of antibiotic structures to improve interactions with bacterial membranes, ultimately leading to more effective, targeted antibiotic therapies with improved pharmacokinetics and reduced resistance potential.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we systematically investigated the complexes formed by SRsC1 and the FQs LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR as well as β-CD and LEVO using NMR and FTIR analyses to gain insights into their stability, stoichiometry, and structural characteristics. Our experimental and theoretical investigations revealed that the complexes between SRsC1 and the FQs (LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR) had a 1:1 stoichiometry. However, complex formation between β-CD and LEVO was experimentally observed to involve a β-CD dimer, which did not align with theoretical predictions. Among the inclusion complexes, SRsC1–CIPRO had the highest stability. Interestingly, LEVO formed a stronger complex with SRsC1 than with β-CD. MD simulations probing the interactions between the host and guest showed the importance of the SO3 groups. Moreover, the computed binding enthalpies agreed with the experimental trends. The spatial characteristics of the inclusion complexes, unveiled through 1D and 2D NMR experiments, indicated the involvement of the piperazine moiety of the FQs in the inclusion process, except in the case of CIPRO. The spectral changes observed following complex lyophilization provided further evidence of complex formation, even in the solid state. Compared to the free FQs, the complexed FQs exhibited enhanced inhibitory effects against resistant P. aeruginosa, with SRsC1–CIPRO showing significant growth inhibition at lower concentrations. We assume that the FQ antibiotics maintain antibacterial activity while in the host–guest complex and that polyphenolic SRsC1 aids in disrupting the bacterial membrane, thereby sustaining the activity, especially for CIPRO complexes. LEVO demonstrated superior activity when complexed with polyphenolic SRsC1 than with β-CD. In addition, the MIC against S. aureus remained consistent for both free and complexed FQs, suggesting better activity against gram-negative bacteria due to a strong correlation between log MIC and log P. Overall, these findings clarify the interaction mechanisms, stoichiometry, and spatial aspects of the inclusion complexes of FQs, which have implications for drug delivery and pharmaceutical applications.

Experimental methods

Complex formation between macrocycles and FQs. SRsC1 was synthesized following a previously reported method34,85; see the supplementary information for details and proton NMR spectra (Fig. S11). All antibiotics (LEVO, NOR, and CIPRO), β-CD, deuterated water (D2O), and sodium deuteroxide (NaOD) solution were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). SRsC1 and each FQ (LEVO, NOR, and CIPRO) were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio in water at room temperature for 24 h. After passing the solution through a 0.45 μm Millipore membrane filter53,86, the solid complex was obtained by freeze-drying (Labconco freeze dryer, USA) for 24 h. Physical mixtures were prepared by blending the host and each FQ in a 1:1 molar ratio. β-CD and LEVO complexes were prepared in a similar manner.

Characterization of complexes

Determination of complex stoichiometry and association (binding) constant via 1H-NMR titration. For each FQ guest (LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR), titrations were carried out with each macrocyclic host (SRsC1 and β-CD)1. To prepare Job plots, 1H-NMR spectra were collected for samples with a fixed total concentration. Stock solutions (0.01 M) of SRsC1 or β-CD and LEVO in D2O as well as SRsC1 and CIPRO or NOR in 5% NaOD in D2O were mixed at different volume ratios at 298 K. The total concentration of host and guest was 0.01 M, and the starting concentration of guest was 0.0 M. The solutions were mixed in different ratios (host:guest, 1:0, 1:1, 1:1.5, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:6, 1:9 and vice versa) and background medium (D2O) was added to give a total volume of 700 µL. After 24 h, the 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV 400 MHz spectrometer. The chemical shift (δobs) of a given nucleus can be expressed using the following formula53,87:

where \(\:\varDelta\:\delta\:={\delta\:}_{G-H}-{\delta\:}_{G}\) is the difference between the proton chemical shifts of the mixture (δG-H) and guest (δG). The total concentration of the mixture (total concentration of host ([H]T) and total concentration of guest ([G]T)) was constant during the titration, but the ratio of host and guest molecules varied. The binding constant (K), also known as the association constant (Ka), of the inclusion complex was calculated by nonlinear parameter fitting of Eq. (2) to the δobs versus [H]T datasets using a solver program based on previous work53.

2D 1H-NMR experiments. DOSY spectra were collected using a stimulated echo pulse sequence88 with two spoil gradients. Smoothed rectangular pulses of 0.66–1.84 ms were used from approximately 50 to 1.0 G/cm in 16 increments with a diffusion time of 60 ms. All NMR datasets were collected using a Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm broadband SmartProbe (USA). The diffusion coefficients were calculated by fitting the peak height as a function of the gradient strength using the “dosy2d” program in Topspin 4.1. This method was used to separate the peaks corresponding to different compounds in the mixtures (SRsC1–LEVO, β-CD–LEVO, SRsC1–CIPRO, and SRsC1–NOR) and to probe multimerization or intermolecular binding.

NOESY/ROESY: The molecular geometry of each complex was investigated using 2D phase-sensitive rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY or NOESY). The structure of the inclusion complex was determined by applying a spinlock of 3 kHz for a mixing time of 0.5 ms. The samples for the 2D NOSEY/ROESY measurements consisted of equimolar solutions of FQ guests and macrocycle hosts at a concentration of 50 mM in 10% NaOD in D2O.

FTIR spectroscopic measurements. IR spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 using a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer and software version OMNIC 7.4.

Computational details: MD simulations. The host–guest combinations SRsC1–LEVO, β-CD–LEVO, SRsC1–CIPRO, and SRsC1–NOR were investigated in the presence of H2O. Before solvation, the host–guest systems were constructed by placing the guest in different orientations around the host. The guest orientations included encapsulation, where the piperazine group or the carboxylic group was oriented within the host cavity through both the upper and lower rims, placing the guest to the side of the host, placing the guest outside the upper or lowerrim, and placing the guest ~10 Å from the upper or lower rim. The isolated host–guest system was minimized, solvated with a 10 Å truncated octahedron with four randomly placed Na+ ions, and then minimized. The solvated system was heated from 0 to 298.15 K over 60 ps. The system was equilibrated using a canonical ensemble (NVT) over 30 ps before running an NPT simulation over 50 ps. Further NPT production runs were carried out for 20 ns to monitor the behavior of the host–guest system. All simulations were carried out with the AmberTools suite of programs89 and visualized with Chimera90. Analysis was performed using CPPTraj91. Complete details can be found in the supporting information.

To further probe the host–guest interactions and determine the binding enthalpy (ΔH), additional simulations were carried out for all the solvated host–guest combinations listed above (with piperazine oriented within the host), solvated hosts (SRsC1 and β-CD), solvated guests (LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR), and the solvent. Each of these systems contained 1500 H2O molecules and 4 Na+ ions. The above-described protocol for minimization, equilibration, and production runs was implemented. To evaluate the binding of the guest by the host (Eq. (3)), ΔH was calculated using Eq. (4), where < E > for each system is the average potential energy. This approach has been implemented in previous studies on the ΔH values of host–guest systems92,93,94. To determine ΔH, the potential energy was sampled every 0.1 ps and the average was found for the 20 ns production run, excluding the first 50 ps, which was used for further equilibration. This uncertainty in the binding affinity was determined via blocking analysis93,95 using a block size of 100 ps. The uncertainty in the binding affinity was determined as shown in Eq. (5).

Antibacterial activity. The in vitro antibacterial activities were tested using gram-positive S. aureus and sensitive and resistant strains of gram-negative P. aeruginosa. A high-throughput method employing a 96-well microtiter plate and serial dilution was used to obtain the MIC values. Briefly, an inoculum of the test organism was grown to mid-log phase in a Luria broth (LB) medium containing 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L sodium chloride. The inoculum was then diluted 1000-fold in the same medium. The bacteria (105 CFU/mL) were inoculated into LB and dispensed at 0.1 mL/well in a 96-well microtiter plate without test compounds. As positive controls, LEVO, CIPRO, and NOR were used. A 50 µL aliquot of the 105 CFU/mL bacterial inoculum was placed in each test well. For each system, except NOR and CIPRO, individual test concentrations were achieved by 2-fold serial dilution with the LB medium. Because of poor solubility, NOR and CIPRO were instead solubilized in 10% v/v DMSO (an inert solvent that does not kill bacteria) in LB media. With S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, the final concentration ranges for the test compounds were 128–0.03 µg/mL and 36–0.06 µg/mL, respectively. The MIC was defined as the concentration of a test compound that completely inhibited bacteria growth during 24 h incubation at 37 °C. Microbial growth in each well was monitored by reading the absorbance at 600 nm using a Biotek Epoch2 microplate reader. All experiments were performed in triplicate. For each measurement, three samples in each replicate were analyzed and data were recorded as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A paired two-tailed t-test was employed for mean comparison, with significance determined at p < 0.05. The data analysis was conducted using Excel.

Determination of partition coefficient. The experimental partition coefficient (Ko/w) between n-octanol and phosphate buffer was determined using the method described by Abuo-Rahma et al49 with slight modifications. Briefly, 80 µL of a sample stock solution (0.3 mg/mL) was diluted with 1.9 mL of phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) and mixed with 2 mL of octanol to mutually sature the organic and aqueous phases. The vials were protected from light by wrapping in aluminum foil. To determine Ko/w of the FQs complexed with hosts (SRsC1 and β-CD), a 10-times more concentrated stock solution (3 mg/mL) of host was added to the FQ-containing aqueous phase (Table S5). The two phases were vortexed for 1 min and agitated at 120 rpm for 24 h in a shaker at 25 ± 0.1 °C. After equilibration, the aqueous phase was removed with a Pasteur pipette. Both phases were analyzed spectrophotometrically to determine the drug concentration. The partition coefficient was calculated as the ratio between the molar concentrations in n-octanol and the aqueous phase using Eq. (6).

where Co and Cw represent the solute concentrations in the octanol and aqueous phases after distribution, respectively; and Vw and Vo represent the volumes of the aqueous and organic phases, respectively. All partition coefficient determinations were performed in triplicate. A microplate reader (Varioskan Lux with SkanIt 4.1 software (USA)) was used for all measurements.

Data availability

All the data relevant to publication (NMR data, computational details) are available in the Supporting Information.

Abbreviations

- SRsC1:

-

Sulfonato-C-methylresorcin[4]arene

- β-CD:

-

β-cyclodextrin

- S. aureus:

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- P. aeruginosa:

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- FQ:

-

Fluoroquinolone

- LEVO:

-

Levofloxacin

- NOR:

-

Norfloxacin

- CIPRO:

-

Ciprofloxacin

References

Levy, S. B. & Bonnie, M. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: Causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10, S122–S129. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1145 (2004).

L, C. A. & Adhar, M. Compositions and methods for affecting virulence determinants in bacteria (2008).

Nathan, C. & Cars, O. Antibiotic resistance—problems, progress, and prospects. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1761–1763. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1408040 (2014).

Walsh, C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro727 (2003).

Fischbach, M. A. & Walsh, C. T. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Sci. (American Association Advancement Science). 325, 1089–1093. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1176667 (2009).

Kirby, W. M. M. Extraction of a highly potent penicillin inactivator from penicillin resistant staphylococci. Sci. (American Association Advancement Science). 99, 452–453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.99.2579.452 (1944).

Medina, E. & Pieper, D. H. Tackling threats and future problems of Multidrug-resistant Bacteria. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 398, 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2016_492 (2016).

Prestinaci, F., Pezzotti, P. & Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathogens Glob. Health 109, 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030 (2015).

Jukes, T. H. Antibiotics in animal feeds and animal production. Bioscience. 22, 526–534. https://doi.org/10.2307/1296312 (1972).

Khuller, G. K., Kapur, M. & Sharma, S. Liposome technology for drug delivery against mycobacterial infections. Curr. Pharm. Design. 10, 3263–3274. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612043383250 (2004).

Khalid, S. et al. Calixarene coated gold nanoparticles as a novel therapeutic agent. Arab. J. Chem. 13, 3988–3996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2019.04.007 (2020).

Wang, X., Ma, L., Li, C. & Yang, Y. W. Macrocycle-based antibacterial materials. Chem. Mater. 36, 2177–2193. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c03322 (2024).

Du, X. et al. Synthesis of Cationic Biphen[4, 5]arenes as Biofilm disruptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301857–n. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202301857 (2023).

Yan, S. et al. Biodegradable Supramolecular Materials Based on Cationic Polyaspartamides and Pillar[5]arene for Targeting Gram-Positive Bacteria and Mitigating Antimicrobial Resistance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, n/a-n/a (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201904683

Li, Q. et al. Construction of Supramolecular Nanoassembly for responsive bacterial elimination and effective bacterial detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 10180–10189. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b00873 (2017).

Wei, T., Zhan, W., Yu, Q. & Chen, H. Smart Biointerface with Photoswitched functions between bactericidal activity and Bacteria-releasing ability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 25767–25774. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b06483 (2017).

Gokel, G. W., Leevy, W. M. & Weber, M. E. Crown Ethers: sensors for ions and molecular scaffolds for materials and Biological models. Chem. Rev. 104, 2723–2750. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020080k (2004).

Zhan, W. et al. Tandem guest-host-receptor recognitions precisely Guide Ciprofloxacin to Eliminate Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62, e202306427. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202306427 (2023).

Martins, J. N. et al. Photoswitchable Calixarene activators for controlled peptide transport across lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13126–13133. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c01829 (2023).

Li, J. J. et al. Lactose azocalixarene drug delivery system for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa infected diabetic ulcer. Nat. Commun. 13, 6279–6279. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33920-7 (2022).

Ji, Q. T. et al. Cucurbit[7]uril-Mediated Supramolecular Bactericidal nanoparticles: their assembly process, controlled release, and Safe Treatment of Intractable Plant Bacterial diseases. Nano Lett. 22, 4839–4847. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c01203 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Supramolecular trap for catching polyamines in cells as an anti-tumor strategy. Nat. Commun. 10, 3546–3548. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11553-7 (2019).

Wang, Z. Q., Wang, X. & Yang, Y. W. Pillararene-based supramolecular polymers for adsorption and separation. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim). 36, e2301721–n. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202301721 (2024).

Li, D., Wu, G., Zhu, Y. K. & Yang, Y. W. Phenyl-extended Resorcin[4]arenes: synthesis and highly efficient iodine adsorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202411261 (2024).

Stevens, D. A. Itraconazole in Cyclodextrin Solution. Pharmacotherapy. 19, 603–611. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.19.8.603.31529 (1999).

Anjani, Q. A. O. X. et al. Inclusion complexes of rifampicin with native and derivatized cyclodextrins: In silico modeling, formulation, and characterization. LID – LID – 20. 10.3390/ph15010020

Kumar, R. et al. Revisiting fluorescent calixarenes: From molecular sensors to smart materials. Chem. Rev. 119, 9657–9721. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00605 (2019).

Saluja, V. & Sekhon, B. S. Calixarenes and cucurbiturils: Pharmaceutial and biomedical applications. J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 4, 16–25 (2013).

Dawn, A., Chandra, H., Ade-Browne, C., Yadav, J. & Kumari, H. Frontispiece: Multifaceted supramolecular interactions from C‐Methylresorcin[4]arene lead to an enhancement in in vitro antibacterial activity of Gatifloxacin. Chem. Eur. J. 23, n/a-n/a (2017).

Kumari, H., Deakyne, C. A. & Atwood, J. L. In Macrocyclic and Supramolecular Chemistry. 325–345 (eds Izatt, R. M.) (Wiley, 2016).

Beyeh, N. K., Valkonen, A. & Rissanen, K. Encapsulation of tetramethylphosphonium cations. Supramol. Chem. 21, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610270802308411 (2009).

Busi, S., Saxell, H., Fröhlich, R. & Rissanen, K. The role of cation⋯π interactions in capsule formation: Co-crystals of resorcinarenes and alkyl ammonium salts. CrystEngComm 10, 1803–1809. https://doi.org/10.1039/b809503e (2008).

Chwastek, M. & Szumna, A. Higher analogues of resorcinarenes and pyrogallolarenes: Bricks for Supramolecular Chemistry. Org. Lett. 22, 6838–6841. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02357 (2020).

Kazakova, E. K. et al. The Complexation properties of the water-soluble tetrasulfonatomethylcalix 4 resorcinarene toward α-Aminoacids. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 43, 65–69 (2002).

Liu, J. L. et al. Functional modification, self-assembly and application of calix[4]resorcinarenes. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 102, 201–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10847-021-01119-w (2022).

Twum, K. et al. Host–guest interactions of Sodiumsulfonatomethyleneresorcinarene and quaternary ammonium Halides: An experimental–computational analysis of the guest inclusion properties. Cryst. Growth. Des. 20, 2367–2376. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01540 (2020).

Twum, K. et al. Functionalized resorcinarenes effectively disrupt the aggregation of αA66-80 crystallin peptide related to cataracts. RSC Med. Chem. 12, 2022–2030. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1md00294e (2021).

Charnley, M. et al. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial resorcinarene-peptides for biomaterial modification. Eur. Cells Mater. 14, 23 (2007).

Panigrahi, S. D. et al. Supramolecule-driven host–guest co-crystallization of cyclic polyphenols with anti-fibrotic pharmaceutical drug. Cryst. Growth. Des. 23, 1378–1388. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.2c00895 (2023).

Fael, H., Barbas, R., Prohens, R., Ràfols, C. & Fuguet, E. Synthesis and characterization of a new norfloxacin/ resorcinol cocrystal with enhanced solubility and dissolution profile. Pharmaceutics. 14, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010049 (2021).

Bofill, L., de Sande, D., Barbas, R. & Prohens, R. A. New and highly stable cocrystal of vitamin D3 for use in enhanced food supplements. Cryst. Growth. Des. 21, 1418–1423. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.0c01709 (2021).

Sanphui, P., Goud, N. R., Khandavilli, U. B. R. & Nangia, A. Fast dissolving curcumin cocrystals. Cryst. Growth. Des. 11, 4135–4145. https://doi.org/10.1021/cg200704s (2011).

Ràfols, C. et al. Dissolution rate of ciprofloxacin and its cocrystal with resorcinol. ADMET DMPK. 6, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.5599/admet.6.1.497 (2018).

Pham, T. D. M., Ziora, Z. M. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. Quinolone antibiotics. MedChemComm. 10, 1719–1739. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9md00120d (2019).

Bush, N. G., Diez-Santos, I., Abbott, L. R. & Maxwell, A. Quinolones: Mechanism, lethality and their contributions to Antibiotic Resistance. Molecules 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25235662 (2020).

Oliphant, C. M. & Green, G. M. Quinolones: A comprehensive review. Am. Fam Phys. 65, 455–464 (2002).

Hooper, D. C. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0702.010239 (2001).

Martínez, J. L. In Antibiotic Drug Resistance (Capelo‐Martínez, J.-L. & Igrejas, G. eds.) 39–55 (Wiley, 2019).

Abuo-Rahma, G. E. D. A. A., Sarhan, H. A. & Gad, G. F. M. Design, synthesis, antibacterial activity and physicochemical parameters of novel N-4-piperazinyl derivatives of norfloxacin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 3879–3886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.027 (2009).

Koga, H., Itoh, A., Murayama, S., Suzue, S. & Irikura, T. Structure-activity relationships of antibacterial 6,7- and 7,8-disubstituted 1-alkyl-1,4-dihydro-4-oxoquinoline-3-carboxylic acids. J. Med. Chem. 23, 1358–1363. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00186a014 (1980).

Foroumadi, A., Emami, S., Mehni, M., Moshafi, M. H. & Shafiee, A. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of N-[2-(5-bromothiophen-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl] and N-[(2-5-bromothiophen-2-yl)-2-oximinoethyl] derivatives of piperazinyl quinolones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 4536–4539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.005 (2005).

Domagala, J. M. et al. New structure-activity relationships of the quinolone antibacterials using the target enzyme. The development and application of a DNA gyrase assay. J. Med. Chem. 29, 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00153a015 (1986).

Szabó, Z. I. et al. Equilibrium, structural and antibacterial characterization of moxifloxacin-β-cyclodextrin complex. J. Mol. Struct. 1166, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.04.045 (2018).

El-Sheshtawy, H. S. et al. A supramolecular approach for enhanced antibacterial activity and extended shelf-life of fluoroquinolone drugs with cucurbit[7]uril. Sci. Rep. 8, 13925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32312-6 (2018).

Suárez, D. F. et al. Structural and thermodynamic characterization of doxycycline/β-cyclodextrin supramolecular complex and its bacterial membrane interactions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 118, 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.01.028 (2014).

Miklasińska-Majdanik, M., Kępa, M., Wojtyczka, R. D., Idzik, D. & Wąsik, T. J. Phenolic compounds diminish antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102321 (2018).

Papuc, C., Goran, G. V., Predescu, C. N., Nicorescu, V. & Stefan, G. Plant polyphenols as antioxidant and antibacterial agents for shelf-life extension of meat and meat products: Classification, structures, sources, and action mechanisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 16, 1243–1268. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12298 (2017).

Macé, S., Truelstrup Hansen, L. & Rupasinghe, H. P. V. Anti-bacterial activity of phenolic compounds against Streptococcus pyogenes. Medicines (Basel Switzerland) 4, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines4020025 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Trojan antibiotics: New weapons for fighting against drug resistance. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.8b00648 (2019).

Kfoury, M. et al. Determination of formation constants and structural characterization of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes with two phenolic isomers: Carvacrol and thymol. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 12, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.3762/bjoc.12.5 (2016).

Fernandes, C. M., Carvalho, R. A., Pereira da Costa, S. & Veiga, F. J. B. Multimodal molecular encapsulation of nicardipine hydrochloride by β-cyclodextrin, hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and triacetyl-β-cyclodextrin in solution. Structural studies by 1H NMR and ROESY experiments. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 18, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-0987(03)00025-3 (2003).

Ulatowski, F., Dąbrowa, K., Bałakier, T. & Jurczak, J. Recognizing the limited applicability of job plots in studying host–guest interactions in supramolecular chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 81, 1746–1756. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.5b02909 (2016).

Yang, B., Lin, J., Chen, Y. & Liu, Y. Artemether/hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin host–guest system: Characterization, phase-solubility and inclusion mode. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 6311–6317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.060 (2009).

Jullian, C., Miranda, S., Zapata-Torres, G., Mendizábal, F. & Olea-Azar, C. Studies of inclusion complexes of natural and modified cyclodextrin with (+)catechin by NMR and molecular modeling. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 3217–3224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2007.02.035 (2007).

Schneider, H. J., Hacket, F., Rüdiger, V. & Ikeda, H. NMR studies of cyclodextrins and cyclodextrin complexes. Chem. Rev. 98, 1755–1786. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr970019t (1998).

Geue, N., Alcázar, J. J. & Campodónico, P. R. Influence of β-Cyclodextrin methylation on host-guest complex stability: A theoretical study of intra- and intermolecular interactions as well as host dimer formation. Molecules (Basel Switzerland) 28, 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28062625 (2023).

Freitas, C. A. B. et al. Assessment of host–guest molecular encapsulation of eugenol using β-cyclodextrin. Front. Chem. 10, 1061624–1061624. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.1061624 (2023).

Alnaqbi, A. M. S., Bhongade, B. A. & Azzawi, A. New validated diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopic method for the quantification of levofloxacin in pharmaceutical dosage form. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 83, 430–436. https://doi.org/10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.791 (2021).

El-Houssiny, A. S. et al. Drug-polymer interaction between glucosamine sulfate and alginate nanoparticles: FTIR, DSC and dielectric spectroscopy studies. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanatechnol. 7, 25014. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6262/7/2/025014 (2016).

Seridi, S., Seridi, A., Berredjem, M. & Kadri, M. Host–guest interaction between 3,4-dihydroisoquinoline-2(1H)-sulfonamide and β-cyclodextrin: Spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1052, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.08.035 (2013).

Zheng, D., Xia, L., Ji, H., Jin, Z. & Bai, Y. A cyclodextrin-based controlled release system in the simulation of in vitro small intestine. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 25, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051212 (2020).

Braegelman, A. S. & Webber, M. J. Integrating stimuli-responsive properties in host-guest supramolecular drug delivery systems.

He, L., Zhang, T., Zhu, C., Yan, T. & Liu, J. Crown ether-based Ion transporters in Bilayer membranes. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202300044-n. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202300044 (2023).

Guo, S. et al. Synthesis and bioactivity of guanidinium-functionalized pillar[5]arene as a biofilm disruptor. Angew. Chem. (Int. ed.) 60, 618–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202013975 (2021).

Birhanu, B. T., Lee, E. B., Lee, S. J. & Park, S. C. Targeting salmonella typhimurium invasion and intracellular survival using pyrogallol. Front. Microbiol. 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.631426 (2021).

Narimisa, N., Amraei, F., Kalani, B. S., Mohammadzadeh, R. & Jazi, F. M. Effects of sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics and oxidative stress on the expression of type II toxin-antitoxin system genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 21, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2019.09.005 (2020).

Zhanel, G. G., Hoban, D. J. & Harding, G. K. Subinhibitory antimicrobial concentrations: A review of in vitro and in vivo data. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 3, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1155/1992/793607 (1992).

Bermejo, M. et al. Validation of a biophysical drug absorption model by the PATQSAR system. J. Pharm. Sci. 88, 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1021/js980370+ (1999).

Cabrera Pérez, M. A., González Dı́az, H., Fernández Teruel, C., Plá-Delfina, J. M. & Bermejo Sanz, M. A novel approach to determining physicochemical and absorption properties of 6-fluoroquinolone derivatives: experimental assessment. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 53, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0939-6411(02)00013-9 (2002).

Beloshe, S. et al. Effect of method of preparation on pioglitazone HCl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Asian J. Pharm. 4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-8398.68470 (2010).

Ross, D. L., Elkinton, S. K. & Riley, C. M. Physicochemical properties of the fluoroquinolone antimicrobials .4. 1-Octanol-water partition-coefficients and their relationships to structure (VOL 88, PG 379, 1992). Int. J. Pharm. 90, 179–179 (1993).

Vázquez, J. L. et al. Determination of the partition coefficients of a homologous series of ciprofloxacin: Influence of the N-4 piperazinyl alkylation on the antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Pharm. 220, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00646-9 (2001).

Bazile, S., Moreau, N., Bouzard, D. & Essiz, M. Relationships among antibacterial activity, inhibition of DNA gyrase, and intracellular accumulation of 11 fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36, 2622–2627. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.36.12.2622 (1992).

Hirai, K., Aoyama, H., Irikura, T., Iyobe, S. & Mitsuhashi, S. Differences in susceptibility to quinolones of outer membrane mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29, 535–538. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.29.3.535 (1986).

Kazakova, E. K. et al. Novel water-soluble tetrasulfonatomethylcalix[4]resorcinarenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 10111–10115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01798-6 (2000).

Cheirsilp, B. & Rakmai, J. Inclusion complex formation of cyclodextrin with its guest and their applications. Bioelectromagnetics 2 (2017).

Jarmoskaite, I., AlSadhan, I., Vaidyanathan, P. P. & Herschlag, D. How to measure and evaluate binding affinities. eLife 9, e57264. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57264 (2020).

Wu, D. H., Chen, A. D. & Johnson, C. S. An improved diffusion-ordered spectroscopy experiment incorporating bipolar-gradient pulses. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A 115, 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmra.1995.1176 (1995).

Case, D. A. et al. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 6183–6191. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01153 (2023).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera-A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20084 (2004).

Roe, D. R., Cheatham, T. E. & PTRAJ,. Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 3084–3095. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct400341p (2013).

Fenley, A. T., Henriksen, N. M., Muddana, H. S. & Gilson, M. K. Bridging calorimetry and simulation through precise calculations of cucurbituril–guest binding enthalpies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 4069–4078. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct5004109 (2014).

Rogers, K. E. et al. On the role of dewetting transitions in host–guest binding free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct300515n (2013).

Ç naro lu, S. S. & Biggin, P. C. The role of loop dynamics in the prediction of ligand-protein binding enthalpy. Chem. Sci. (Cambridge) 14, 6792–6685. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc06471e (2023).

Flyvbjerg, H. & Petersen, H. G. Error estimates on averages of correlated data. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.457480 (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by HK (AFOSR and Discretionary Research Funds). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Ramana Mittapalli Reddy for his invaluable assistance with the synthesis of the polyphenolic macrocycle, Prof. Carol A. Deakyne for her insightful discussions regarding the computational work, and Olivia K. Meyer for discussions regarding the computational analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. S.P. and H.K. conceived the project and designed the research work experiments. S.P. conducted all the experiments. Computational calculations were carried out by K.C.K., E.N.R., and C.M.M. Antibacterial activity studies were designed and carried out by S.P. under the guidance of N.K. The manuscript was prepared by S.P., and computational details were added by C.M.M. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by H.K. (PI) and N.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panigrahi, S.D., Klebba, K.C., Rodriguez, E.N. et al. Enhancing antibacterial efficacy through macrocyclic host complexation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics for overcoming resistance. Sci Rep 14, 24637 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73568-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73568-5