Abstract

Intracranial hemorrhage is a critical emergency that requires prompt and accurate diagnosis in the emergency department (ED). Deep learning technology can assist in interpreting non-enhanced brain CT scans, but its real-world impact on clinical decision-making is uncertain. This study assessed a deep learning-based intracranial hemorrhage detection algorithm (DLHD) in a simulated clinical environment with ten emergency medical professionals from a tertiary hospital’s ED. The participants reviewed CT scans with clinical information in two steps: without and with DLHD. Diagnostic performance was measured, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. Consistency in clinical decision-making was evaluated using the kappa statistic. The results demonstrated that DLHD minimally affected experienced participants’ diagnostic performance and decision-making. In contrast, inexperienced participants exhibited significantly increased sensitivity (59.33–72.67%, p < 0.001) and decreased specificity (65.49–53.73%, p < 0.001) with the algorithm. Clinical decision-making consistency was moderate among inexperienced professionals (k = 0.425) and higher among experienced ones (k = 0.738). Inexperienced participants changed their decisions more frequently, mainly due to the algorithm’s false positives. The study highlights the need for thorough evaluation and careful integration of deep learning tools into clinical workflows, especially for less experienced professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intracranial hemorrhage is a potentially catastrophic neurological emergency requiring prompt attention as neurological deterioration frequently occurs within the initial hours following its onset1,2,3. This circumstance, with a substantial mortality rate of up to 45% and severe functional impairment among survivors, underscores the need for timely medical care for patients presenting to the emergency department (ED)4,5,6,7. Non-enhanced brain computed tomography (CT) serves as a primary diagnostic modality due to its noninvasive and rapid nature in the ED in cases of central nervous system emergencies, such as acute traumatic brain injury and intracranial hemorrhagic lesions8. Therefore, accurate identification of the type and location of acute intracranial hemorrhage through brain CT scans is crucial for guiding subsequent clinical management of these conditions. Furthermore, it holds significant implications in determining the need for emergent surgical intervention and the selection of appropriate surgical approaches9.

The field of clinical medicine has witnessed marked progress in the integration of deep learning technology. While various deep-learning solutions for diagnosing intracranial lesions are gradually being incorporated into radiology and have demonstrated considerable diagnostic capabilities10,11,12,13,14, their applicability and utility in clinical practice remain largely uncertain.

Deep learning-based assistive algorithms are compelled to focus on aiding individuals in decision-making rather than completely replacing physicians by autonomously making diagnoses. This is primarily due to their limited applicability across all patients and their inability to meet the diverse objectives of all physicians. Extensive implementation of such solutions as clinical decision support systems necessitates comprehensive evaluation within the clinical workflow of end-use physicians15,16,17,18.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of utilizing a deep learning-based assistive intracranial hemorrhage detection algorithm (DLHD) on the interpretation of non-enhanced brain CT scans and decision-making through a simulation-based interventional design.

Methods

Study design and participants

This simulation-based prospective interventional study was conducted using a web-based questionnaire. Participants for the study were recruited through an official notice as part of a research project operated by The National IT Industry Promotion Agency under the Government of South Korea. Participants included in the study were individuals aged 18 years or older, including board-certified emergency physicians, residents undergoing emergency medicine training, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) working at the study site’s ED. Participants who did not comprehend the study content or withdrew after agreeing to participate were excluded. The study was conducted at an emergency center within a tertiary hospital that had a total of 18 board-certified emergency physicians, 29 residents undergoing emergency medicine training, and 5 EMTs with nationally certified licenses. Among them, three board-certified emergency physicians, two senior residents, three junior residents, and two EMTs voluntarily participated in the study, resulting in a total of ten participants. The participants’ work experience in the ED varied, with two emergency physicians having 89 months of experience; one, 53 months; two, 41 months; one EMT, 9 months; one EMT, 6 months; and three emergency physicians, 5 months of experience. Emergency medical professionals with less than 24 months of experience were classified as “inexperienced.” All participants received detailed information regarding the study purpose and the mechanics of the simulation system. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, South Korea (approval number 4-2023-0821) and adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were provided with an explanation of the study before enrollment, and informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Boards of Severance Hospital approved the study and granted a waiver of documentation, waiving the requirement for written informed consent.

Selection of clinical data

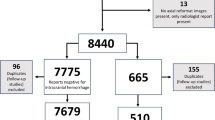

A total of 2596 patients underwent non-enhanced brain CT scans in the ED between July and December 2022. The study included adult patients aged 18 years and above who were initially assessed in the ED. Among the collected brain CT data, 450 cases of follow-up CT scans ordered by physicians other than those in the ED were excluded. The DLHD’s interpretations were assessed for intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). True positives occurred when the DLHD correctly identified ICH, false positives when incorrectly identifying ICH in its absence, false negatives when failing to identify present ICH, and true negatives when correctly identifying absent ICH. For simulation, relevant information such as the patient’s present illness, vital signs, and past medical history were extracted from electronic medical records. Then, an unbiased ED physician independently assessed the radiological and clinical evidence presented by each brain CT scan for study. Among the 2146 cases, since cases without intracranial hemorrhage could dominate due to the emergency department’s clinical environment, the DLHD’s interpretations of all cases were compared with the radiologist’s official readings and classified into true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. A total of 111 cases were randomly selected to ensure statistical significance while maintaining an even distribution within these four categories. Each case included their associated clinical data and three questionnaires, enabling assessment of interpretation performance and decision-making effect. This approach allows for a balanced evaluation of clinical decisions across various scenarios. These anonymous datasets were automatically obtained using the clinical research analysis portal developed by the hospital’s digital healthcare department.

Deep learning-based assistive intracranial hemorrhage detection algorithm

Brain non-enhanced CT images were analyzed using deep learning software (JBS-04 K; JLK Inc., Korea), which was approved by the Korea Food and Drug Administration for clinical use. The algorithm was developed using 6963 brain CT scans with intracranial hemorrhage and 6963 without intracranial hemorrhage from the Artificial Intelligence Hub directed by the Korean National Information Society Agency. All hemorrhage lesions on CT images were manually segmented by neuroradiologists. Taking intracranial hemorrhage subtypes into account, five deep learning models were developed using 2D U-net with the Inception module 1, 2: lesion segmentation model, lesion subtype pre-trained segmentation model, subdural hemorrhage model, subarachnoid hemorrhage model, and small (< 5 mL) lesion segmentation model19. Dice loss function, Adam optimizer, and learning rate of 1e-4 were used for the model training. Following this, five base models were ensembled using weighting values derived from a deep learning-based weighted model in which input data consisted of 5-channel segmentation results from five base models with a range of 0–1. Using random initiative weight values, the weighted model was trained to minimize Dice loss between predicted segmentation and ground-truth segmentation. Five different hemorrhage detection models and the weighted ensemble model yielded five segmentation outputs and weight values per slice, respectively. The segmentation outputs and weight values were then multiplied, and the pixel probability with the highest value was selected as the maximal probability at the slice level20.

The protocol of prospective simulation for performance assessment

The prospective simulation sessions conducted in this study were meticulously designed to align with the patient management process in the ED of the study site. Performance assessment was carried out in individual rooms under the supervision of a researcher. Participants were presented with brain CT findings, accompanied by the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, including age, sex, chief complaint, and vital signs. The participants received access to a monitor screen displaying the patient’s relevant clinical information and the CT scan. The simulation session consisted of two sequential steps, recorded using a web-based form (Google Forms; Google, Mountain View, CA). In the first step, participants were tasked with scrutinizing the provided CT scan for abnormalities and making clinical decisions concerning the need for further diagnostic studies and the appropriate disposition of the patient. They relied solely on the provided clinical information without incorporating a deep learning algorithm. Following the first step, participants were given a washout period of approximately one day before proceeding to the second step21. In each round of the study, the order of the cases was randomized to help minimize potential biases. This randomization aimed to reduce the likelihood that the last N cases in the unaided arm would be presented in close proximity to the first N cases in the aided arm, mitigating the risk of carryover effects due to the short washout period. Here, they examined the same cases; however, the CT scans were provided with the deep learning algorithm and clinical information. Participants were not allowed to alter their responses from the first step, and all subsequent responses were recorded in real time. The brain CT image was provided to the participants in the form of video footage that could be scrolled. Only the axial view was available, with the brightness and size of the image not adjustable. There were no imposed time constraints for participants to complete the simulation.

Definition of the reference standard

Retrospective annotation of brain imaging served as the reference standard to determine the presence of intracranial hemorrhage. A panel of seven board-certified neuroradiologists, each with a minimum of 8 years of experience, meticulously reviewed the CT scans while considering relevant previous imaging findings and other pertinent clinical information extracted from medical records. Notably, they were blinded to any information regarding the use of DLHD.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables are presented using counts and percentages, while the chi-square test was utilized to examine differences between groups. Continuous variables are reported as median (q1, q3), and between-group differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. To evaluate the performance of interpretation, various measures, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), were computed. These measures were calculated for each individual participant and then aggregated for all participants. The level of agreement in clinical decision-making was assessed using the kappa statistic, with k values categorized as minor agreement (< 0.20), fair agreement (0.21–0.40), moderate agreement (0.41–0.60), high agreement (0.61–0.80), and excellent agreement (> 0.80)22. Within-participant comparisons of AUROC estimates were conducted using the DeLong test, while between-participant comparisons were performed using the multi-reader multi-case ROC method. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy parameters were compared using the generalized estimating equation method. Kappa statistics were compared using the bootstrap method. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical software SAS (version 9.4, SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and the “MRMCaov” and “multiagree” R packages (version 4.2.3, http://www.R-project.org) were used for data analyses.

Results

Table 1 presents an overview of the diagnostic performance of DLHD assessed using 2146 CT scans conducted at the study site. DLHD showed a sensitivity of 70.81 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66.65–74.97), specificity of 86.72 (95% CI: 85.10–88.34), accuracy of 83.32 (81.74–84.90) and AUROC of 0.788 (0.765–0.810). The negative and positive predictive values of DLHD were 59.20 and 91.61, respectively.

Of the 111 cases selected for the prospective simulation study, there were 32 true-positive cases, 27 true-negative cases, 24 false-positive cases, and 28 false-negative cases for the diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage (Figs. 1 and 2). The average age of included patients was 62.7 years, with 73.9% being male. Fifteen patients (13.5%) had a history of tumors, and three (2.7%) had previous brain operations.

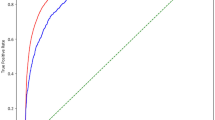

Table 2 displays the impact of using DLHD on the diagnostic performance of emergency professionals. When comparing cases with and without algorithm assistance, the sensitivity of the inexperienced group increased significantly from 59.33 to 72.67% (p < 0.001), while the specificity decreased from 65.49 to 53.73% (p < 0.001). However, no statistically significant differences were observed in terms of accuracy and AUROC depending on whether the algorithm was utilized or not. Conversely, in the experienced group, no statistically significant differences were observed in sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and AUROC, depending on the use of DLHD.

Table 3 summarizes the results regarding the consistency of clinical decision-making with the use of deep learning-assisted interpretation. The overall kappa values were 0.594 (95% CI: 0.533–0.655) for interpretation of CT images and 0.586 (95% CI: 0.539–0.633) for deciding the disposition of ED patients, respectively. For the experienced group, the kappa values were 0.769 (95% CI: 0.702–0.836) for interpretation of CT images and 0.738 (95% CI: 0.687–0.789) for deciding the disposition of ED patients, indicating considerable consistency. However, for the inexperienced group, the values were significantly lower, with a kappa value of 0.421 (95% CI: 0.296–0.546) for interpretation of CT images and 0.425 (95% CI: 0.362–0.488) for deciding the disposition. Inconsistent opinions were observed in brain CT interpretation, decision of disposition, and reasoning for decisions when employing the deep learning assistive technique. Notably, these changes in clinical decisions were more frequent in inexperienced emergency medical professionals compared to experienced ones (p < 0.001).

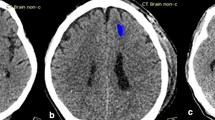

Among experienced emergency medical professionals, the utilization of DLHD (Deep Learning-based Hemorrhage Detection) resulted in changes in the disposition of an average of 19 out of 111 cases. These changes were due to the identification of previously unnoticed hemorrhagic lesions that required observation or admission, which were aided by DLHD, resulting in an average rate of change of 17.9%. In contrast, among inexperienced emergency medical professionals, changes in disposition were observed in an average of 38 out of 111 cases. The average rate of change specifically due to newly identified hemorrhagic lesions using DHLD was 45.3%, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of DLHD on the decision-making process of emergency medical professionals in a clinical environment. Our findings revealed that sensitivity to detect intracranial hemorrhage increased when utilizing DLHD among inexperienced emergency medical professionals. Moreover, this study indicates minimal influence of the algorithm on experienced participants’ ability to detect hemorrhages and make clinically informed decisions. In contrast, inexperienced participants were significantly influenced by the algorithm’s output.

DLHD can enhance sensitivity in detecting abnormalities on brain CT scans. When interpreting these scans, experienced clinicians conduct targeted interpretation of imaging studies and may identify incidentally discovered abnormal findings along with cerebral hemorrhages. However, our observations revealed that inexperienced emergency professionals were significantly more influenced by the algorithm in both hemorrhage detection and the decision-making processes, relying more on annotation aids compared to their experienced counterparts. Notably, the algorithm occasionally misclassifies not only hemorrhages but also other lesion types, such as tumors and benign abnormalities, as hemorrhages23,24. Differentiating intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) from conditions like parenchymal calcifications, dural patches, and tumors poses challenges due to the similarities in the hyperdensities of these anomalies. Moreover, deep learning-induced misclassifications can occur with typical hyperdensities caused by calcifications of various structures in the brain. Hence, clinicians must meticulously examine these structures to accurately differentiate between actual presence in the blood and misclassifications25,26. Inexperienced emergency professionals face difficulties in accurately distinguishing between these lesion types, making them more susceptible to false positives generated by the algorithm. In this study, after encountering 24 false-positive cases among those detected by the algorithm, average interpretation changes of 12.5% and 38.3%, respectively, were observed in the experienced and inexperienced groups. Overall, inexperienced professionals showed greater dependence, leading to changes in clinical decisions. This highlights the need for cautious implementation and comprehensive evaluation of deep learning solutions in the clinical workflow of EDs. Therefore, deep learning-based assistive technology should be considered as a screening tool rather than a definitive diagnostic tool.

Previous studies have primarily focused on the diagnostic performance of automatic detection algorithms25,27,28,29. However, conducting practical validation before implementing this technology in clinical practice is crucial to ensure its effectiveness and practicality for end-users30. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effects of deep learning-based CT annotation solutions on clinical decision-making in emergency medical professionals. To simulate real-world clinical scenarios, we provided participants with comprehensive patient information, including medical histories, chief complaints, vital signs, and brain CT findings, all of which play important roles in clinical practice alongside imaging results. This was vital as emergency medical professionals base their decisions on multiple factors, considering both brain CT results and overall clinical evaluation rather than relying solely on imaging.

The ED prioritizes rapid screening for critical illnesses, necessitating timely management. Non-enhanced brain CT scans are particularly effective and efficient in evaluating ED patients with central nervous system symptoms, including headaches, mental status deterioration, and other neurological deficits31,32. The ability to screen critical findings from non-enhanced brain CT results is crucial, especially in the ED33. Therefore, it is imperative to emphasize the need for heightened sensitivity in diagnostic assistance; implementing a solution that facilitates the triage of abnormalities rather than providing definitive diagnoses would be practical. In under-resourced hospitals with resource constraints resulting in a single physician covering the entire department or during frequently understaffed night shifts, or when residents who may have limited experience are responsible for the interpretation34,35,36,37, the implementation of deep learning-based CT annotation solutions can provide valuable support for patient safety to enhance the sensitivity of detecting intracranial hemorrhages in brain CT scans.

When interpreting these results, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, as this study was based on simulations, the findings may not precisely reflect real-world cases. The simulation did not include profound physical and neurological examination, laboratory results, and focused history-taking, which are important components of the decision-making process. Second, the deep learning-based CT annotation solution used in this study had a limited target range, which may have restricted the identification of other abnormalities in brain CT scans. Future research should explore algorithms that encompass a broader target range. Third, the changes in clinical decisions reported in this study did not necessarily correlate with improved clinical outcomes. Finally, selection bias is possible as all participants were emergency medical professionals working in the same ED. Therefore, the recommendations for clinical decisions presented in the simulation may not be generalizable to all emergency medical professionals. Furthermore, although the 1-day washout period aimed to prevent participants from acquiring answers or additional information between the two experiments, thereby potentially enhancing the significance of AI’s impact, the short interval between readings could result in participants remembering their initial responses. This could artificially enhance the performance of the AI-assisted second reads. Further studies are required with varying washout periods to validate our findings and address any residual concerns about recall bias.

In conclusion, the utilization of DLHD had variable effects on the diagnostic performance and decision-making of emergency medical professionals. The study underscores the importance of comprehensive evaluation and careful integration of deep learning solutions in the clinical workflow, particularly for inexperienced professionals. Further research is warranted to assess the algorithm’s impact on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and its generalizability across diverse clinical settings.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Qureshi, A. I. et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl. J. Med.344, 1450–1460. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105103441907 (2001).

Elliott, J. & Smith, M. The acute management of intracerebral hemorrhage: a clinical review. Anesth. Analg.110, 1419–1427. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d568c8 (2010).

Jolink, W. M. et al. Time trends in incidence, case fatality, and mortality of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology85, 1318–1324. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002015 (2015).

Hemphill, J. C. et al. 3rd Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke46, 2032-60. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000069 (2015).

Cordonnier, C., Demchuk, A., Ziai, W. & Anderson, C. S. Intracerebral hemorrhage: current approaches to acute management. Lancet392, 1257–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31878-6 (2018).

González-Pérez, A., Gaist, D., Wallander, M. A., McFeat, G. & García-Rodríguez, L. A. Mortality after hemorrhagic stroke: data from general practice (the Health Improvement Network). Neurology81, 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829e6eff (2013).

Béjot, Y. et al. Temporal trends in early case-fatality rates in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology88, 985–990. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003681 (2017).

Alobeidi, F. & Aviv, R. I. Emergency Imaging of Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. Neurosci.37, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000437110 (2015).

Morotti, A. & Goldstein, J. N. Diagnosis and management of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Emerg. Med. Clin. North. Am.34, 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2016.06.010 (2016).

Olive-Gadea, M. et al. Deep learning based software to identify large vessel occlusion on noncontrast computed tomography. Stroke51, 3133–3137. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030326 (2020).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open.2, e191095. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1095 (2019).

Weikert, T. et al. Automated detection of pulmonary embolism in CT pulmonary angiograms using an AI-powered algorithm. Eur. Radiol.30, 6545–6553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-06998-0 (2020).

Yeo, M. et al. Review of deep learning algorithms for the automatic detection of intracranial hemorrhages on computed tomography head imaging. J. Neurointerv Surg.13, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-017099 (2021).

Seyam, M. et al. Utilization of artificial intelligence–based intracranial hemorrhage detection on emergent noncontrast CT images in clinical workflow. Radiol. Artif. Intell.4(2), e210168. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.210168 (2022).

Buchlak, Q. D. et al. Effects of a comprehensive brain computed tomography deep learning model on radiologist detection accuracy. Eur. Radiol.34(2), 810–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-10074-8 (2024).

Davis, M. A., Rao, B., Cedeno, P. A., Saha, A. & Zohrabian, V. M. Machine learning and improved quality metrics in acute intracranial hemorrhage by noncontrast computed tomography. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol.51(4), 556–561. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2020.10.007 (2022).

Kim, J. H., Han, S. G., Cho, A. & Shin, H. J. Effect of deep learning-based assistive technology use on chest radiograph interpretation by emergency department physicians: a prospective interventional simulation-based study. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak.21, 311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01679-4 (2021).

Seyam, M. et al. Utilization of artificial intelligence-based intracranial hemorrhage detection on emergent noncontrast CT images in clinical workflow. Radiol. Artif. Intell.4, e210168. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.210168 (2022).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Intervention MICCAI234, 41. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1505.04597 (2015).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S. & Shlens, J. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In 2016 IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2818-26. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1512.00567 (2016).

Park, S. H. et al. Methods for clinical evaluation of artificial intelligence algorithms for medical diagnosis. Radiology306(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.220182 (2023).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics33, 159–174 (1977).

Arbabshirani, M. R. et al. Advanced machine learning in action: identification of intracranial hemorrhage on computed tomography scans of the head with clinical workflow integration. NPJ Digit. Med.1, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-017-0015-z (2018).

Rava, R. A. et al. Assessment of an artificial intelligence algorithm for detection of intracranial hemorrhage. World Neurosurg.150, e209–e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.02.134 (2021).

Voter, A. F., Larson, M. E., Garrett, J. W. & Yu, J. J. Diagnostic accuracy and failure mode analysis of a deep learning algorithm for the detection of cervical spine fractures. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.42, 1550–1556. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7179 (2021).

Bello, H. R. et al. Skull base-related lesions at routine head CT from the emergency department: pearls, pitfalls, and lessons learned. Radiographics39, 1161–1182. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019180118 (2019).

Wismuller, A. & Stockmaster, L. A prospective randomized clinical trial for measuring radiology study reporting time on artificial intelligence-based detection of intracranial hemorrhage in emergent care head CT. Proc. SPIE11317, 253. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2002.12515 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health1, e271–e97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30123-2 (2019).

Chodakiewitz, Y. G., Maya, M. M. & Pressman, B. D. Prescreening for intracranial hemorrhage on CT head scans with an AI-based radiology workflow triage tool: an accuracy study. J. Med. Diag Meth8, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.35248/2168-9784.19.8.286 (2019).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal.42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Bekelis, K. et al. Computed tomography angiography: improving diagnostic yield and cost effectiveness in the initial evaluation of spontaneous nonsubarachnoid intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg.117, 761–766. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.7.JNS12281 (2012).

Blacquiere, D. et al. Intracerebral hematoma morphologic appearance on noncontrast computed tomography predicts significant hematoma expansion. Stroke46, 3111–3116. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010566 (2015).

Delgado Almandoz, J. E. et al. Diagnostic accuracy and yield of multidetector CT angiography in the evaluation of spontaneous intraparenchymal cerebral hemorrhage. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.30, 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1546 (2009).

Sellers, A., Hillman, B. J. & Wintermark, M. Survey of after-hours coverage of emergency department imaging studies by US academic radiology departments. J. Am. Coll. Radiol.11, 725–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2013.11.015 (2014).

Strub, W. M., Leach, J. L., Tomsick, T. & Vagal, A. Overnight preliminary head CT interpretations provided by residents: locations of misidentified intracranial hemorrhage. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.28, 1679–1682. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0653 (2007).

Platon, A. et al. Emergency computed tomography: how misinterpretations vary according to the periods of the nightshift? J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr.45, 248–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/RCT.0000000000001128 (2021).

Arendts, G., Manovel, A. & Chai, A. Cranial CT interpretation by senior emergency department staff. Australas Radiol.47, 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.01204.x (2003).

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical AI Clinic Program through the National IT Industry Promotion Agency, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Project number S1313-22-1003, H0124-23-1006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. and J.H.K. conceived and designed the study, and J.H.K. obtained research funding. S.Y.C. and A.C. supervised the conduct of the study and data collection. J.H.K. and H.S.C. managed the data, including quality control. S.Y.C. and S.L. were in charge of initial data mining and cleansing, and E.H.K. analyzed the data. S.Y.C. and A.C. drafted the manuscript, and J.H.K and A.C. contributed to its revision. S.Y.C. and J.H.K. contributed equally. A.C. assumes the overall responsibility for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, South Korea (approval number 4-2023-0821) and adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were provided with an explanation of the study before enrollment, and informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Boards of Severance Hospital approved the study and granted a waiver of documentation, waiving the requirement for written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, S.Y., Kim, J.H., Chung, H.S. et al. Impact of a deep learning-based brain CT interpretation algorithm on clinical decision-making for intracranial hemorrhage in the emergency department. Sci Rep 14, 22292 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73589-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73589-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Artificial intelligence in nephrology: predicting CKD progression and personalizing treatment

International Urology and Nephrology (2025)