Abstract

To investigate the relationship between long-term use of low-dose aspirin and Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection, and its effect on eradication and recurrence of HP. According to the results of C14-Urea Breath Test (C14-UBT), 3256 patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases from March 2019 to December 2020, were divided into HP infection group and non-infection group. Univariate and multivariate was used to investigate the relationship between Low-dose aspirin use and HP infection. 859 patients with hypertension combined with HP infection were divided into aspirin group, non-aspirin group and control group, the eradication rate after 2 weeks of bismuth-containing quadruple drug treatment and the recurrence rate after 1,3 year were compared. The overall infection rate of HP was 53.3%. The results of univariate analysis showed that the infection rate of female, age, BMI, LDL-C, FBG of HP infected group was higher than non-infection. The infection rate of patients who took low-dose aspirin was higher than no-aspirin [56.6% vs. 51.3%, χ2 = 8.548, P = 0.003]. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis showed that long-term aspirin use still increased the risk of infection (OR = 1.433, 95% CI 1.196–1.947, P < 0.001). The Per-Protocol analysis showed that the overall eradication rate was 87.6%, and among the eradication rates of aspirin group, non-aspirin group and control group were not statistically significantly (87.8%, 88.5%, and 86.6%, respectively), The Intention-To-Treat analysis showed that the overall eradication rate was 84.3%, and the eradication rates among the three groups were not statistically significantly. The overall 1-year recurrence rate was 1.3%, and the recurrence rates of the three groups were no statistical significance. The overall 3-years recurrence rate was 3.1%, and the recurrence rate of aspirin group was higher than non-aspirin group and control group (5.30%, 1.90% and 1.70%, respectively, χ2 = 6.118, P < 0.05). The main adverse reactions in the first month of eradication treatment were constipation and mild nausea, and there was no statistical significance between the three groups. Long-term use of low-dose aspirin increases the risk of HP infection and the recurrence rate in 3 years after eradication. It is suggested that HP should be tested and eradicated regularly in long-term users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, studies have shown that Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection is associated with the development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases1. Low-dose aspirin (i.e. 75–100 mg once daily), used for prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, can cause gastrointestinal mucosal damage and increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding2. It remains unclear whether long-term use of low-dose aspirin increases the risk of HP infection or whether it affects the eradication and recurrence of HP. This study retrospectively analysed the correlation between HP infection and long-term use of low-dose aspirin and compared the effect of long-term use of low-dose aspirin on the eradication and recurrence of HP through a prospective case-control study.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

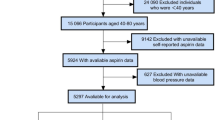

Using retrospective analysis, 3256 patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) who were treated at the Affiliated Hospital of Gansu University of Chinese Medicine, the Second People’s Hospital of Zhangye City in Gansu, the Tianshui Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine in Gansu, and the First Hospital of Lanzhou University between March 2019 and December 2020 were included in this study. There were 2147 males (65.9%) and 1109 females (34.1%) aged 34–93 (51.9 ± 9.1) years.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who underwent C14-urea breath test (C14-UBT) for the first time. (2) Patients who had lived in the local area for at least 1 year and (3) Patients that had been clearly diagnosed with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (including coronary heart disease, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, cerebrovascular diseases, peripheral arterial diseases, and others)for at least 1 year and had been given or not given the relevant treatments;

Patients who had been regularly taking low-dose enteric-coated aspirin tablets (daily dose = 100 mg) orally for at least 1 year. According to the C14-UBT results, the subjects were divided into an HP infection group (+) with 1733 patients and an HP noninfection group (−) with 1523 patients. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Those who had incomplete disease history data; (2) Those who had diabetes, severe liver and kidney dysfunction, a history of malignant tumours, or a history of abdominal surgery; (3) Those who had used various types of antimicrobials (Cephalosporin, Nitroimidazole, Penicillins, Macrolides), Proton Pump inhibitors (Omeprazole, Esomeprazole, Rabeprazole) in the last 2 months and those who had been taking other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Indomethacin, Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Celecoxib) for at least 3 month; and (4) Those who were pregnant or lactating.

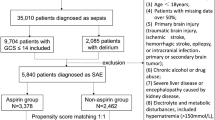

A prospective case-control study was conducted. Considering the diverse symptoms, complex conditions, and multiple medications associated with other cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, this study subjects were limited to Hypertension patients who were willing to eradicate therapy. Finally, a total of 859 Hypertension with HP infection patients were selected as the research subjects.

There were 568 males (66.1%) and 291 females (33.9%) aged 43–71 (50.3 ± 8.4) years. According to medication status, the patients were divided into the following groups: (1) Aspirin group, 432 patients who were treated with aspirin in addition to the routine use of antihypertensive drugs; (2) non-aspirin group, 427 patients who only used antihypertensive drugs routinely; and (3) control group, 418 patients with HP infection but without various acute or chronic diseases during the same period. They were not statistically significant in the age, blood pressure, BMI, FBG and TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG and UA. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) alcohol or tobacco addiction; (2) blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg; and (3) ≥ 3 risk factors, target organ damage, clinical complications and comorbidities such as diabetes, and other acute and chronic diseases.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University and followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was not obtained for this cross-sectional study, but the personal information of the study subjects was kept confidential. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for the case-control study.

Methods

-

1.

The following clinical data were collected: (1) Inclusion baseline information: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking history, and past medical history. (2) Laboratory tests and indicators: routine blood test, fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triacylglycerol (TG), uric acid (UA), homocysteine (Hcy) and C14-UBT. Abdominal ultrasound, cardiac colour Doppler ultrasound, arterial ultrasound of the neck and extremities, and brain computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (3) Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases; CVDs include various types of coronary heart disease, valvular disease, myocardial disease, and arrhythmia; cerebrovascular diseases include cerebral infarction, cerebral arteriosclerosis, transient ischaemic attack, and intracranial carotid plaque; and peripheral artery disease includes disease of the upper and lower extremity arteries, celiac artery, and extracranial carotid artery. (4) Medication status: doses and time courses of proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics and aspirin.

-

2.

Diagnosis, eradication and efficacy evaluation of HP infection: (1) Diagnostic criterion: C14-UBT count/min > 100 dpm/mmol. When the C14-UBT count was close to 100 dpm/mmol, the test was performed again after 2 weeks. (2) The eradication regimen was as follows: esomeprazole magnesium enteric-coated tablets (20 mg, 2 times/day, taken before breakfast and dinner; AstraZeneca Plc, product batch number: 1603178); bismuth potassium citrate/potassium citrate/clarithromycin/tinidazole tablets (bismuth potassium citrate tablets: 220 mg, 2 times/day, taken on an empty stomach half an hour before breakfast and dinner; tinidazole tablets: 0.5 g, 2 times/day, after breakfast and dinner; clarithromycin tablets: 0.25 g, 2 times/day, after breakfast and dinner (Livzon Pharmaceutical Group, product batch number: 160903)), with a treatment course of 2 weeks. (3) Evaluation of efficacy: The efficacy evaluation was performed 1 month after the end of eradication treatment and 1 year after successful eradication according to the original method, and the diagnostic criteria were the same. The eradication rate was calculated separately (Per-Protocol analysis = the number of successful eradication cases/the number of enrolled patients receiving treatment × 100%, and Intention-To-Treat analysis = the number of successful eradication cases/the number of patients who completed the eradication treatment × 100%). Recurrence rate = number of patients experiencing recurrence / (number of patients with successful eradication – number of patients lost to follow-up) × 100%.

-

3.

Antihypertensive treatment and safety evaluation: (1) Antihypertensive treatment: After conducting risk stratification assessments of cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical target organ damage and clinical diseases, the original antihypertensive regimen determined based on patient lifestyle was remained the same and was continually administered to the patients. (2) The subjects were urged to take the medication regularly and record adverse reactions, and liver and kidney function indicators were reviewed.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. Measurement data conforming to normal distribution are expressed as \(\:\bar{x}\pm s\), and comparisons between the two groups were made using a t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); measurement data not conforming to normal distribution are expressed as median (quartiles) [M (Q1, Q3)], and the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical variables were expressed as the case number or percentage, and the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact probability test were used. Variables with statistical significance (or close to statistical significance) according to univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model, and the risk factors for HP infection were determined using a regression analysis. A two-sided P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics of 3256 study subjects and clinical status

The overall HP infection rate was 53.3% (1733/3256). The univariate analysis showed that the infection rate in females was greater than in males [56.4% (625/1109) vs. 51.6% (1108/2147), χ2 = 6.628, P = 0.010], the age of the HP infected group were higher than the uninfected group (52.1 ± 9.2 vs. 50.4 ± 8.9, t = 3.166, P = 0.002), the BMI of the HP infected group was higher than the uninfected group (24.59 ± 3.11 vs. 24.36 ± 3.01, t = 2.135, P = 0.033), LDL-C was higher than that of uninfected group (2.36 ± 0.61 vs. 2.29 ± 0.57, t = 3.174, P = 0.002), FBG was higher than that of uninfected group (5.35 ± 0.53 vs. 5.22 ± 0.52, t = 2.519, P = 0.024).

There were 1191 patients who used small doses of aspirin for a prolonged period of time, accounting for 36.6% (1191/3256) of the patients examined in this study. The HP infection rate of patients who used aspirin was greater than that of patients who did not use aspirin [56.6% (674/1191) vs. 51.3% (1059/2065), χ2 = 8.548, P = 0.003], while the differences in infection rate between the groups that used aspirin for 1–2 years, ≥ 2–< 5 years, and ≥ 5 years were not statistically significant [54% (95/176) vs. 57% (211/370) vs. 57.1% (238/417), χ2 = 0.533, P = 0.758] (Table 1).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with HP infection

HP infection was used as the dependent variable, and age, sex, LDL-C, FBG, and long-term use of low-dose aspirin were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis as independent variables. Results showed that the risk of HP infection increases with age (OR = 1.041, 95% CI 1.008–1.086, P = 0.003); women have a greater risk of infection than men (OR = 1.332, 95% CI 1.098–1.627, P = 0.004); long-term use of aspirin can increase the risk of infection (OR = 1.526, 95% CI 1.231–2.015, P < 0.001); the risk of infection increases with increased FBG (OR = 1.528, 95% CI 1.337–2.189; P < 0.001); the risk of infection increases with increased LDL-C levels (OR = 1.103, 95% CI 1.034–1.392, P = 0.007). After controlling for age, sex, BMI and other factors, long-term use of aspirin was still found to increase the risk of infection (OR = 1.433, 95% CI 1.196–1.947, P < 0.001).

HP eradication and recurrence after 1 year and 3 years

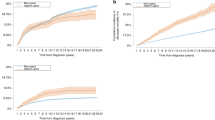

The per-protocol analysis showed that the overall eradication rate was 87.6% (1077/1229), and the eradication rates among the aspirin group, the nonaspirin group and the control group were 87.8% (367/418), 88.5% (361/408), and 86.6% (349/403), respectively, and were not statistically significantly different (χ2 = 0.667, P = 0.607). The Intention-To-Treat analysis showed that the overall eradication rate was 84.3% (1077/1277), and the eradication rates among the three groups were 84.9% (367/432), 84.5% (361/427), and 83.5% (349/418) respectively, and were not statistically significantly different (χ2 = 0.364, P = 0.843).

A total of 31 patients were lost to the 3-year follow-up, and the loss rate was 2.90% (31/1077). The overall 1-year recurrence rate was 1.3% (14/1046); the recurrence rates of the 3 groups were 1.10% (4/359), 1.70% (6/352), and 1.20% (4/335), respectively; and the recurrence rates among the groups were not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.547, P = 0.761).

The 3-year overall recurrence rate was 3.1% (32/1046), and the recurrence rates of the 3 groups were 5.30% (19/359), 1.90% (7/352), and 1.70% (6/335), respectively; the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 9.214, P = 0.01). The recurrence rate in the aspirin group was significantly greater than that in the nonaspirin group and the control group (χ2 = 6.118 and 5.507, respectively, P = 0.01 and 0.015). There was no significant difference between the nonaspirin group and the control group (χ2 = 0.036, P = 0.537) (Fig. 1).

Safety evaluation

There were no abnormal changes in indicators such as liver or kidney function after 1 or 3 years of eradication treatment. The main adverse reactions that occurred within 1 month of the eradication treatment/follow-up were constipation, mild nausea, abdominal distension, dry mouth, bad breath, headache, and fatigue, and the differences in adverse reactions among the three groups were not statistically significant (all P > 0.05, Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Low-dose aspirin is widely used to prevent various cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events3. The long-term use of aspirin can cause gastrointestinal mucosal damage and increase the incidence of gastrointestinal haemorrhage, with a marked age-dependence (i.e., higher mortality in the elderly)2,4. Ageing is strongly associated with an increased risk of HP infection2, but it is not clear whether the increased risk of HP infection is associated with the use of aspirin. In this study, the univariate analysis showed that the HP infection rate in long-term low-dose aspirin users was greater than that in nonusers, and the multivariate regression analysis also showed that long-term use of low-dose aspirin was associated with an increased risk of HP infection. The risk of infection remained high and statistically significant when controlling for factors, such as age and sex5. The possible cause is related to the effect of the salicylates produced by the hydrolysis of aspirin on factors of the gastric environment, such as the pH, and these changes favour the passage of HP across the mucus barrier and subsequent colonization.

In the middle-age and elderly populations, HP infection is an important risk factor for aspirin-associated peptic ulcers6, and combined HP infection increases risks of bleeding and perforation in aspirin users7. Currently, the combination of aspirin use and HP infection is considered to have an enhanced effect on gastric mucosal damage8,9. The damage caused by aspirin to the gastric mucosa is mainly due to cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) inhibition and prostaglandin depletion, leading to a reduced defence-repair capacity of the gastric mucus-mucosal barrier and mucosal ischaemia10. Moreover, HP can secrete a variety of pathogenic factors that trigger immune and inflammatory responses11,12 and aggravate gastric mucosal injury. Yoshida13 reported that HP tends to evade the immune response in the stomach, which is disrupted by aspirin, and can colonize and multiply in the gastric mucosa for a prolonged period of time. HP infects the gastric mucosa and induces the accumulation of neutrophils, which is an important process that exacerbates the damaging effect of aspirin on the gastric mucosa14. The 2022 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation statement emphasized that for people ≥ 60 years old, the bleeding risk of aspirin could offset the benefit of CVD prevention15. Therefore, elderly individuals that use aspirin should be carefully monitored for HP infection and treated with an eradication treatment protocol if HP infection is present to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding and recurrence16,17.

This study also showed that there was no significant difference in the infection rate between the groups treated with aspirin over different periods of time, which was consistent with the results reported in the literature18. It is also unclear whether long-term use of low-dose aspirin affects the eradication of HP. This study used the 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for HP eradication, and the effects were basically consistent with those of the 10-day classic quadruple regimen commonly used in China19. The difference in the eradication rate between the aspirin and nonaspirin groups was not statistically significant. A previous study confirmed5 that the aspirin use and course of treatment did not affect the HP eradication rate. Therefore, long-term use of low-dose aspirin did not affect the efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for HP eradication, and patients did not experience serious adverse reactions during treatment.

The recurrence rate of HP varies greatly in different regions and among different populations. A study focusing on people 18–65 years old in 18 hospitals in 15 provinces in China showed that the annual reinfection rate after the first HP eradication in China was 1.5%/year20. It remains unclear whether patients who use low-dose aspirin for a long time are more likely to experience recurrence. This study showed that the overall recurrence rate after HP eradication was 1.3%; the comparison of the recurrence rates among the three groups was not statistically significant. The overall 3-year recurrence rate was 3.1%, while that of the aspirin group was 5.30%, which was higher than that of the nonaspirin group and the control group.

In summary, we believe that long-term use of low-dose aspirin can increase the risk of HP infection and the 3-year recurrence rate after eradication but cannot affect the efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for HP eradication. Moreover, patients do not experience severe adverse events during the eradication treatment regardless of aspirin use.

This study provides evidence for the possible correlation between aspirin use and HP infection. However, there are certain limitations. This study was a retrospective study and could not determine the sequence of aspirin use and HP infection. In view of the significant efficacy of aspirin in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, how to use aspirin rationally to maximize its efficacy and reduce adverse reactions has become an important research topic. This study provides a reference for clinical decision-making and the treatment of HP.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Ju, L. & Hao, C. Research progress of Helicobacter pylori infection and cardiovascular disease [J]. Chin. J. Intern. Med. 61(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20210105-00015 (2022).

Cuzick, T. M. A. Prophylactic use of aspirin: systematic review of harms and approaches to mitigation in the general population [J]. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 3 0(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9971-7 (2015).

Arnett, D. K. et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines [J]. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. v74(10), 1376–1414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.009 (2019).

Iwakiri, S. N. & Tsuruoka, R. A case-control study of the risk of upper gastrointestinal mucosal injuries in patients prescribed concurrent NSAIDs and antithrombotic drugs based on data from the Japanese national claims database of 13 million accumulated patients[J]. J. Gastroenterol. 53 (12), 1253–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-018-1483-x (2018).

Zhou Yun, C. & Yibo, L. Correlation between long-term aspirin use and Helicobacter pylori infection in the elderly and its effect on eradication efficacy.[J]. Chin. J. Geriatr. 43 (3), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254s-9026.2024.03.004 (2024).

Nguyen, C. T. et al. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in special patient populations [J]. Pharmacotherapy 39(10), 1012–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2318 (2019).

Tsai, T. J. et al. Upper gastrointestinal lesions in patients receiving clopidogrel anti-platelet therapy [J]. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 111(12), 705–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2011.11.028 (2012).

Chey, W. D. et al. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection[J]. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112(2), 212–239 (2017).

Lanza, F. L., Chan, F. K. & Quigley, E. M. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID related ulcer complications [J]. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104(3), 728–378. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.115 (2009).

Cryer, B. et al. Effects of cutaneous aspirin on the human stomach and duodenum[J]. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians. 111, 448–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/paa.1999.111.5.448 (1999).

Chan, F. K. et al. Expression and cellular localization of COX-1 and – 2 in Helicobacter pylori gastritis[J]. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15 (2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00918.x (2001).

Tatsuguchi, A. et al. Localisation of cyclooxygenase 1 and cyclooxygenase 2 in Helicobacter pylori related gastritis and gastric ulcer tissues in humans[J]. Gut. 46 (6), 782–789. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.46.6.782 (2000).

Yoshida, N. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection potentiates aspirin induced gastric mucosal injury in Mongolian gerbils[J]. Gut. 50 (5), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.50.5.594 (2002).

Feldman, M. et al. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroduodenal injury and gastric prostaglandin synthesis during long term ⁄ low dose aspirin therapy: a prospective placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial[J]. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96 (6), 1751–1757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03928.x (2001).

US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation Statement. Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease [J]. JAMA. 327(16), 1577–1584. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4983 (2022).

Sarri, G. L. et al. Helicobacter pylori and low-dose aspirin ulcer risk: a meta-analysis[J]. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34 (3), 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14539 (2019).

Chan, F. K. et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and risk of peptic ulcers in patients starting long-term treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomized trial[J]. Lancet. 359 (9300), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736 (2002).

García Rodríguez, L. A. et al. Bleeding risk with long-term low-dose aspirin: a systematic review of observational studies[J]. PLoS One. 11 (8), e0160046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160046 (2016).

Zheng, Q. et al. Comparison of the efficacy of triple versus quadruple therapy on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance[J]. J. Dig. Dis. 11 (5), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00457.x (2010).

Xie, Y. et al. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori reinfection and its risk factors after initial eradication: a large-scale multicentre, prospective open cohort, observational study[J]. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9 (1), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1737579 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by Hospital fund of The First Hospital of Lanzhou University (ldyyyyn2023-46); Science and technology Project of Gansu Province (Key Research and Development Program, 21YF5FA120);Gansu Province Health Industry Research Project (GSWSKY2020-12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y., and L.S., wrote the main manuscript text. Q.Y. prepared figures and tables. Z.L, Z.X., Y.S., B.L., provided research work support, data collection. Corresponding author’s name is Liu Shixiong, He directly involved in the design and implementation of the research; collect and analyze data, write articles, and obtain research funding; Support and guide experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (No. LDYYLL2022-02), Signed written informed consents were obtained from the patients and/or guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Qiao, Y., Zhao, L. et al. Association of long-term use of low-dose aspirin with Helicobacter pylori infection and effect on recurrence rate. Sci Rep 14, 22084 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73661-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73661-9