Abstract

In this study, four Artificial intelligence (AI) - based machine learning models were developed to estimate the Residual compressive strength (RCS) value of concrete supported with nano additives of Nanocarbon tubes (NCTs) and Nano alumina (NAl), after exposure to elevated temperatures ranging from 200 to 800 degrees. These models were developed via adapting meta- heuristic models including the Water cycle algorithm (WCA), Genetic algorithm (GA), and classical AI models of Artificial neural networks (ANNs), Fuzzy logic models (FLM), in addition to the statistical method of Multiple linear regression (MLR). 156 post heating experimental results available as a literature data (represents four input parameters of temperature change, heat exposure duration, nanomaterial type, and replacement proportion) are used to achieve the study’s objective. Results of the developed models demonstrated that ANN and FLM have strong potential in predicting RCS. However, it is often infeasible to generate practical equations that relate input and output variables from these models. Upon analysing the results of the WCA and GA, it was found that WCA yielded the most accurate predictions based on all performance indicators. Furthermore, RCS prediction equations with superior accuracy were derived utilizing the meta-heuristic AI models of WCA and GA, with Mean absolute errors (MAEs) of 3.09 kg/cm² and 3.53 kg/cm² for the training, 1.91 kg/cm² and 2.72 kg/cm² for the validation, and 1.91 kg/cm² and 2.72 kg/cm² for the testing data sets, respectively. Additionally, sensitivity analysis via neural networks weights and SHAP investigation were performed to reveals the impact and relationship of the input variables with the output variables. Both techniques reveal that temperature degree and time of exposure had the highest positive impact on RCS value, followed by NAl and NCTs, in order.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete exposure of high elevated temperatures commonly has a major effect on its mechanical properties, which can lead to structural failure and loss of functionality when temperatures extend a specific threshold or when exposed to high temperatures over an extended duration1. Exposure to elevated temperatures induces a series of transformations in concrete, including both physical and chemical changes. These changes entail the evaporation of water, disintegration of hydration compounds and aggregates, expansion of the microstructure, mass loss, and an increase in porosity2. Additionally, spalling, caused by elevated water vapor pressure and thermal stresses, can occur3. Such modifications are accountable for the degradation of concrete’s mechanical properties (specially the compressive strength) under high-temperature conditions.

Critical temperature thresholds govern specific physical and performance variations in concrete. Above 105 °C, the release of chemically bonded water from cement hydration products, such as Calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and Calcium hydroxide (Ca-OH) leads to microcracking as the cement paste undergoes dehydration. Although elevated temperatures can initially accelerate the hydration process, they can also cause premature cessation of hydration in later stages, resulting in lower strength development4. Furthermore, the differential thermal expansion between the aggregate and cement paste can create tensile stresses and lead to cracking in the interfacial transition zone due to varying rates of thermal expansion. Additionally, the dehydration and decomposition of cement minerals induce structural changes in the cement matrix, leading to increased porosity and friability. The decomposition of calcium hydroxide into calcium oxide further contributes to the formation of microcracks. When temperatures exceed 550 °C, pressurizing gases generated from chemical reactions can cause networking and longitudinal cracks within the cementitious binder network, significantly reducing its load-bearing capacity for the various mechanical stresses5. Similarly, exposure to 800 degrees Celsius often leads to a significant reduction in compressive strength, translating to approximately 50% of its original value, along with a mass loss exceeding 10%6. Concrete’s performance and structural functionality considerably diminish when temperatures range from 1000 to 1200 degrees Celsius, resulting in substantial mass loss and a notable decrease in mechanical strength7. It is worth emphasizing that the choice of aggregates in the concrete mix plays a pivotal role in compressive strength reduction following high-temperature exposure. Siliceous aggregates demonstrate the highest expansion and inflict the most severe damage. In contrast, calcareous aggregates, such as limestone and dolomite, exhibit lower thermal expansion than siliceous aggregates, resulting in less harm to concrete with calcareous aggregates compared to siliceous concrete8,9,10. Table 1 provides a summary of the most significant effects and decomposition stages resulting from elevated temperatures up to 800 degrees Celsius as highlighted by (Arioz, 2007)5. Due to the significant effects of high temperatures on the behavior and resistance of concrete, improving its performance under high-temperature conditions through the use of various types of additives has been an active area of research for many years11. Among the modern materials used in this field are nanomaterial additives, Various materials such as nano-silica12, nano-Ferrite13, nano- calcium carbonate14, Nano alumina (NAl)15, Nanocarbon tubes (NCTs)16, nano metakaolin8, and other different types17, have been successfully employed in different replacement or addition proportions to enhance the mechanical strength values of concrete exposed to high temperature conditions.

The current study represents an extension of a previous investigation18, where the authors utilized different ratios of NCTs and NAl individually and in a combined mixes to achieve the optimum replacement ratios with cement while enhancing the residual compressive strength (RCS) values following exposure to various temperatures ranging between 200 and 800 degrees Celsius for one to two hours. The values of other variables that could affect the RCS, such as the proportions of the concrete mixture (aggregates, admixtures, W/C ratio), were kept constant to capture the impact of the investigated nanomaterial additives. The obtained experimental results were utilized as a data set to develop a prediction and simulation model of RCS values using artificial neural networks (ANN). The developed model demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting RCS values with a regression value of 0.9877. However, it was not feasible via the ANN to develop a predictive equation that directly relates all input variables to the final output of the dependent variable, which is RCS.

A total of 156 results for the RCS values, reflecting 12 different replacement ratios of NCTs and NAl, whether in individual or combined ratios, were obtained. Besides the redevelopment of the ANN prediction model, these results formed the basis for constructing a database used to develop predictive models employing diverse AI – bases machine learning methods, including fuzzy logic models (FLM), genetic algorithm (GA), and water cycle algorithm (WCA). The WCA, utilized sparingly in previous studies focused on concrete behavior and optimal concrete mixture design, is introduced in this research to simulate and predict RCS values following exposure to high temperatures. Furthermore, through the adaptation of GA and WCA algorithms, a highly accurate predictive equations were derived, establishing a connection between RCS value and all influencing input variables which are temperature degree, heat exposure period, as well as the type and percentage of nano material replacements.

It is worth noting that earlier studies aimed at developing prediction and simulation machine learning models for the behavior of concrete, especially the RCS after elevated temperatures exposure, are quite few in number yet. In addition, studies related to predicting the behavior of concrete reinforced with nano additives, particularly its compressive strength, are extremely rare. The positive effect of nano additives in concrete is usually attributed to one of two explanations: they either act as fillers that fill the voids in the microstructure of the concrete, or they function as pozzolanic materials that serve as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) that help in the improvement and continuity of hydration reactions. High temperatures have accompanying physicochemical effects that, in turn, impact the mechanical properties of nano concrete. The strength of these effects is related to the nature of the nano materials used, as well as additional factors concerning the concrete mix and curing conditions. Therefore, predicting the behavior of nano concrete after exposure to high temperatures and correlating this with the numerous influencing variables is a promising research area, especially given the limited studies that have addressed this aspect. Furthermore, studies that have succussed in developing accurate prediction equation for the RCS values can be counted in on one hand. The difficulty in developing such models is attributed to the multitude of variables that can contribute to the RCS value. These variables could be related to the concrete composition such as types of cement, concrete cover thickness, type and ratios of the used aggregates, W/C ratio, types and proportions of mineral admixtures, chemical additives, and cement replacement materials when used. The other affecting variables are related to the surrounding conditions such as temperature degree, heat exposure period, heat source whether elevated temperature or a direct fire or flames effects, and the cooling regimes. This wide range variable also complicates the task of deriving accurate and comprehensive predictive equations for concrete behavior following exposure to high temperatures. Therefore, any study or predictive model is always constrained within the boundaries of the values and variables on which it is based.

Literature review and research significance

Concrete research has evolved through four distinct phases: empiricism, theory, regression analysis-based computations and data driven-based metaheuristic algorithms. Initially, empirical approaches relied on trial-and-error methods to achieve desired concrete properties, but this approach was time-consuming and resource-intensive. While effective for some applications, it became impractical for complex mixtures due to the exponential increase in experiments needed. In the theoretical phase, which began in the 1980s, microstructural models of cement hydration provided insights into the relationship between microstructure and properties. These models, based on fundamental principles of kinetics, thermodynamics, and mechanics, aimed to simulate the hydration process and microstructure development of cementitious systems. However, their accuracy depended heavily on complex data and experimental observations, posing challenges for generalizability. The advent of regression analysis based computational science in the 2000s marked the third phase, leveraging tools like density-functional theory (DFT) and classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. These first-principal models offer insights into concrete behavior at atomic and molecular scales, particularly focusing on phases like C-S-H gel, a key product of cement hydration. While computationally intensive, these simulations provide valuable structural and kinetic data, complementing experimental studies. Despite these advancements, challenges persist. Concrete’s complexity, stemming from its diverse mixture constituents and variability in properties, complicates the process of understanding its behavior. Iterative trial-and-error cycles, high computational costs, and the need for extensive domain expertise remain significant obstacles.

Integrating the three paradigms of empiricism, theory, and computation can significantly advance our comprehension of concrete materials. By blending empirical, theoretical, and computational approaches, researchers can surmount existing challenges, fostering more efficient and sustainable concrete design and construction practices. Furthermore, a fourth paradigm is emerging in concrete research: data-driven science, spearheaded by artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) techniques. Recently, DL techniques like recurrent neural network and long-short-term memory network have gained significant traction in civil engineering19. DL models have proven to be highly effective and reliable in predicting various concrete properties, especially when large datasets are available20. Their ability to handle vast amounts of data and uncover complex patterns makes them particularly advantageous in this field. On the other side, ML models are autonomously uncovering implicit patterns and extract valuable insights, accommodating the intricate nature of concrete mixtures and properties21. They serve as potent tools in elucidating process–structure–property–performance relationships, identifying cement hydration mechanisms, and aiding concrete materials design and discovery, alongside high-throughput experimentation and computation22.

Among ML approaches, ANN are a flagship method for estimating mechanical characteristics like the RCS of concrete under elevated temperatures (Table 2). Before the detailed presentation and corresponding commentary on the works presented in this table, it is worth noting that only qualitative findings can be drawn. A comparison between the different works becomes unfeasible as each study uses different input parameters, as well as a different number of data points. This is because the input parameters and the amount of data points used in each study may vary significantly, making it challenging to directly compare them. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from the comparison should be qualitative rather than quantitative.

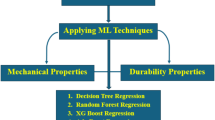

Uysal and Tanyildizi (2012)23 studied 12 variables, including temperature and cement quantity, to develop an ANN model for self-compacting concrete, achieving high prediction accuracy (R² = 0.9757). Similarly, Harun Tanyildizi (2018)24 employed ANN and Support Vector Machine algorithms to predict the RCS of carbon fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete, achieving R² values of 0.9902 and 0.9701, respectively. Ashteyat and Ismeik (2018)25 utilized 332 literature datasets to construct an ANN model for self-compacting concrete RCS, achieving an R² value of 0.9443. Similarly, there are similar studies where researchers have successfully employed ANN for prediction and simulation purposes regarding the compressive strength of concrete after exposure to high temperature effects. This was conducted for various types of concrete, including High strength concrete26, Rubberised concrete32, Ordinary concrete33, Self-consolidating concrete34, Nano additives concrete18, and Fiber reinforced concrete35. All of these developed models demonstrated a high predictive capability and achieved high accuracy. However, none of them was able to derive a predictive equation that could be used directly instead of the neural network model. Moreover, it was not possible to formulate predictive equations for concrete behavior after exposure to high temperatures using other AI methods such as FLM, K nearest neighbor, AdaBoost, Random Forest, Decision tree, Convolutional neural networks, and Weibull distribution33,34,35,36,37. From this perspective, the significance of metaheuristic algorithms such as WCA and GA becomes evident. Their adaptability in generating equations that precisely characterize the behavior of input and output variables is demonstrated through the execution of numerous iterations until getting the optimum solve with the lowest possible errors. One of the rare studies that succeeded in developing a predictive equation for RCS of ordinary and high strength concretes after exposure to high temperatures using the metaheuristic GA expression programming was conducted by (Alaskar et al., 2023)28. Utilizing 207 available actual results representing 8 input variables, the formulated equation achieved good R2 value of 0.854 with low error statistical indices of mean absolute errors (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE) at 5.536 MPa, and 0.030 MPa, respectively. The WCA has also been employed in a few previous studies to develop predictive equations for the compressive strength behavior of concrete as a result of various variables, while exposure to high temperatures wasn’t one of them38,39. Given the available literature studies up to the current study date, this research targets to address the gap in the existing literature related to predicting the post heating compressive strength of nano concrete using ANN, FLM, GA, and WCA. Additionally, the predictive equations developed using the WCA and GA techniques that which achieved superior R2 values exceeding 0.9858 and 0.9748 for the testing datasets, in order, represent a research significance of the current study. Such high accuracy nonlinear equations. The development of such highly accurate nonlinear predictive equations represents a significant contribution to this study, as there are hardly any similar equations in the literature studies concerning the prediction of the behavior of concrete exposed to high temperatures. Furthermore, Shapley Additive explanation (SHAP) method was integrated as a novel sensitivity analysis technique with ML technique to analyze the significance and impact of individual and combined variables on RCS predicted values.

Methodology

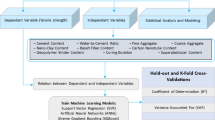

In this section, the methodology employed to achieve the objectives of the current study will be outlined. The first objective involves accurate prediction and simulation processes using various AI techniques (ANN, FLM, WCA, and GA) to assess the impact of replacing cement with different proportions of nano-additives, including CNTs and Nal, on the value of RCS after elevated temperature exposure. Furthermore, the authors seek to derive precise predictive nonlinear equations for estimating RCS values based on the changing values of the four input variables using both the WCA and GA. To reach these objectives, 156 actual RCS values obtained via the experimental program of our previously published study18 were employed as data sets to develop the proposed models and equations. Temperature degree, Exposure time, NAl % (as replacement of cement content), and CNTs % (as replacement of cement content) are considered as the input variables of the AI models, while RCS represents the sole output. Seven specimen results were selected randomly for the simulation process. To maintain consistency and better performance of the developed AI models, it is necessary to scale the inputs and outputs of the study which have varying ranges to a uniform range. The common approach is to scale the data in a range between zero and one. In the current study, the use of logarithmic equations in the basic algorithms makes it impractical to use zero in these modes. To overcome this limitation, all the data is rescaled between 0.1 and 0.9 as described in Eq. (1) highlighted is the study of (Sobhani et al.2010)40.

where i represents the primitive value of data, Si is the value of data after scaling, and imax and imin are the values of maximum and minimum values of primitive data, in the order mentioned. Tables 3 and 4 introduce the experimental raw data values of compressive strength used to develop the four machine learning models in addition to the multiple linear regression (MLR) model. Using these results, RCS values after high elevated temperature were calculated using Eq. 2. The reason for adopting the values of RCS as outputs of the developed models instead of the direct values of compressive strength after elevated temperature exposure is attributed to the fact that initial compressive strength before heat exposure is an influencing factor in its value after heat exposure. Since the initial compressive strength values cannot be experimentally controlled like the other main four input variable in this study, the prediction models were designed considering the RCS value, which links the compressive strength value before and after exposure to high temperature, as the sole output. The standard deviation, maximum, minimum, and average amount of primitive data used to develop the AI predictive models in this study are displayed in Table 5. Table 6 presents the equations required to scale parameter values used in various AI applications to the interval of 0.1 to 0.9. After excluding 7 random results for the simulation process as shaded in Tables 3 and 4, the remaining 149 experimental data are divided into three groups; 70% of the specimens are used as a training subset (105 samples), 15% as validation subset (22 samples), and 15% as testing subset (22 samples). To assess the performance and evaluate the accuracy of the developed models, five statistical performance indices were calculated for each model results: MAE, mean square error (MSE), RMSE, \(\:{R}^{2}\), and correlation coefficient (R). The formulas for these statistical coefficients, represented by Eqs. (3–7), were utilized in the calculation process.

where (\(\:\:EXPi\)), (\(\:\:\stackrel{-}{EXPi}\)), (PRE\(\:i\)), (\(\:\:\stackrel{-}{PRE}i\)), and n are the actual RCS values, average of actual data, predicted data, average of predicted data, and the number of specimens, orderly. The R index, with a range of 0 to 1 and an ideal value of 1, indicates the appropriateness of the chosen predictors in predicting the target variable. On the other hand, the RMSE and MAE, both with a range of 0 to + 1 and an ideal value of 0, serve as measures to assess the accuracy of the predictions, where higher values indicate lower accuracy. The various techniques of the used machine learning models are implemented, and the outcomes of these models besides the conventional regressions are assessed for the training and testing datasets.

Meta-heuristic algorithms

Machine learning techniques commonly operate as black boxes, unable to explain how they produce outputs from given inputs. Various machine learning techniques such as ANN and FLM can be adapted to describe and solve problems under study with the aim of prediction and simulation of data, while achieving superior accuracy levels41. However, reaching predictive equations that describe the complex (often nonlinear) relationships between input and output variables of these model has always been a challenge in these techniques. To asses this shortcoming, metaheuristic-based programming can be employed, as it is unbiased and adaptable to various model structures. This study utilizes two metaheuristic algorithms of WCA and GA to estimate the values of RCS after elevated temperature exposure, and to derive predictive equations that describe the relation between the varying input factors and the sole output of RCS value. Each input is evaluated using 8000 distinct modes. These modes consist of two constants and one function, with 20 different options assignable to the symbolic constants and the function. The algorithms select the most effective option from these 8000 possibilities. The functions served by the inputs are: sine(x), cosine(x), tangent(x), cotangent(x), log10 (x), log2 (x),\(\:{x}^{2},\:{x}^{3},\sqrt[2]{x}\), \(\:\sqrt[3]{x}\) ,\(\:\:\:\frac{1}{x}\), \(\:\frac{1}{{x}^{3}}\), \(\:\frac{1}{{x}^{3}}\), exp(x), \(\:{2}^{X}\),\(\:\:{3}^{X}\),\(\:\:{4}^{X}\), x, -x\(\:\sqrt{2}\) ,and-x\(\:\sqrt{3}\).

To generate the final input format, the constant values and the input function are multiplied. To enhance the model’s authenticity and structural adaptability, 400 different combination functions are employed to combine the final input format. These combination functions include logarithmic functions with diverse bases, trigonometric functions (sine, cosine, tangent, and cotangent), radical functions, exponential functions, in addition to various combinations of these functions. The metaheuristic machine learning techniques exhaustively search the feasible region to identify the optimal combination of input constants, input functions, and the inverse form of the combination functions. Each algorithm is run ten times, and the obtained formula with the highest accuracy is selected as the final algorithm’s result. Hence, the most precise model is chosen to predict RCS values.

Water cycle algorithm

WCA is an effective metaheuristic algorithm that was invented by (Eskandar, et al. 2012)42 to mimic the natural flow of water to intelligently find optimal or near-optimal solutions of complex problems. WCA was inspired by the hydrological cycle, where rivers and streams naturally follow their paths towards the oceans and seas, as cleared in Fig. 1. This cycle involves processes like evaporation, precipitation, and surface runoff. In WCA, each solution vector represents a potential solution which is treated as a raindrop. In each iteration, the solution vectors are evaluated based on their objective function values. The most promising solution vector that akin to the sea receives special attention43. The remaining solution vectors are categorized into rivers and streams based on their relative performance. Streams, representing fewer promising solutions are moved towards rivers and the sea, which represent better solutions. Rivers with relatively good solutions are also moved closer to the sea, indicating further improvement. This process mimics the gradual movement of water from streams to rivers and eventually to the sea. The evaporation operation is triggered when the distances between rivers and the sea or streams and rivers fall below a predefined threshold, known as the evaporation rate. This mechanism simulates the natural process of evaporation, where water droplets in rivers and streams evaporate and return to the atmosphere44. During the evaporation phase, new solution vectors that represents potential solutions are randomly generated, similar to raindrops. These new solution vectors are compared to the existing ones. If a new solution vector outperforms the existing ones, it replaces the existing vector. However, if a new solution vector proves to be less effective than the existing ones, it is discarded. This process continues until a predetermined stopping criterion is met. The number of iterations is commonly used as the stopping criterion. Ultimately, the best solution represented by the sea is identified as the optimal solution to the problem39. The MATLAB implementation of the WCA in this study involves tuning the algorithm’s parameters. Specifically, the number of raindrops, iterations, rivers and seas components, as well as the constant for the evaporation condition, are set to 500, 7000, 8, and a random number that is less than 0.1, in order. Figure 2 displays the flow chart of the adjusted WCA used to solve this problem. It outlines the steps and processes involved in the algorithm’s execution. Despite the recent invention of WCA, it has been widely adopted in various studies associated with solving complex problems related to optimization. More specifically in the fields of designing concrete mixtures and predicting concrete behavior, WCA has found significant application where the majority of published studies affirmed its high efficiency and superior capability. (Naseri et al., 2020)39 adopted three meta-heuristic algorithms of WCA, GA, and soccer league competition algorithm to design various sustainable concrete mixes and to develop a predictive equation of the compressive strength values based on the variation of 11 input factors representing 16 mixes design. The predictive equation developed via WCS showed the best performance indices through the three algorithms with R2 value of 0.936. Similar equations could be developed by (Naseri et al., 2020)38 with the aim of predicting the compressive strength of fly ash concrete. Once again, the developed equation through WC achieved better performance, as measured by various statistical indices, compared to the other techniques with R2 value of 0.89 for the testing dataset. (Ashrafian et al., 2020)45 used WCA to optimize multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) prediction model process of lightweight foam concrete’s compressive strength. The combined MARS-WCA model exhibited significantly superior predictive capabilities for the compressive strength variable in comparison to other methods. Utilizing the WCA meta-heuristic algorithm facilitated highly efficient internal calibration of the MARS model parameters, enhancing its overall predictive accuracy. In a study by (Naseri et al., 2022)46, WCA was utilized alongside a novel metaheuristic model called coyote optimization programming to achieve optimal design expressed through the compressive strength of various sustainable concrete mixtures. The findings indicate that implementing these innovative optimization techniques in the design of concrete mixture proportions can lead to a significant reduction in the overall cost, amounting to 36.6%. Additionally, it is possible to develop hybrid models between WCA and other AI techniques. This approach has the potential to harness the superior optimization capabilities of WCA to develop improved models for these techniques, effectively tackling diverse challenges in construction engineering. Among these challenges, WCA has proven to be highly accurate in structural damage determination, estimation of bearing capacity of foundations, design of truss structures, pavement maintenance and rehabilitation scheduling, and prediction of high-performance concrete behavior47.

Genetic algorithm

GA is a well-established metaheuristic optimization algorithm that mimics the natural process of evolution to identify improved solutions within the feasible region. It draws inspiration from Darwin’s principles of natural selection, employing a mechanism of survival of the fittest to guide the search for optimal solutions48. GA represents a classic metaheuristic optimization technique inspired by the natural process of evolution. In this approach, each solution vector is represented as a chromosome, composed of genes that correspond to specific data characteristics. The population, encompassing all chromosomes, is initialized randomly and updated in each iteration. Three fundamental operators drive the generation of a new population: selection, crossover, and mutation. During the selection phase, pairs of solution vectors, referred to as parents, are chosen. The crossover operation combines these parents to generate offspring, introducing new genetic combinations. The mutation operator, on the other hand, randomly modifies certain genes in each solution vector, ensuring genetic diversity. After creating the new population, the current and generated populations are evaluated based on an objective function, and the fittest chromosomes are retained. Meanwhile, inferior chromosomes are eliminated from the population. This iterative process continues until a termination criterion, such as a predefined number of iterations, is met. The best chromosome, representing the optimal solution vector, is then identified and reported. This study employs three selection operators simultaneously: roulette wheel selection, random selection, and tournament selection. This approach aims to explore a broader range of solutions and cover more regions within the feasible solution space. Additionally, double-point crossover is utilized to enhance the efficiency of the crossover operator. In this study, the selection operators for the genetic algorithm are chosen to be tournament selection, random selection, and roulette wheel selection. One of these operators is randomly selected for each selection process. Furthermore, a two-point (double point) crossover technique is employed to enhance the coverage of the data. After executing the algorithm, the genetic parameters are adjusted and calibrated. The population size, number of iterations, crossover percentage, mutation rate, and mutation percentage are set to 500, 7000, 0.8, 0.1, and 0.2, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the GA cycle inspired by the natural selection of genes. The flow chart of the GA utilized in this study is presented in Fig. 4. This flow chart outlines the steps and processes involved in the genetic algorithm, providing a visual representation of its operation.

Evolutionary optimization models such as GA can play a pivotal role in the optimization of material compositions and mix designs, considering several factors like mechanical properties, workability, sustainability indices, and cost49. By exploring a vast solution space, GAs can uncover innovative and efficient material combinations that may be hard to find through traditional methodologies. In a study by (Lim et al., 2004)50, GAs were employed for designing optimal proportions and additives in the production of high-performance concrete. GAs helped reduce the number of experimental attempts required to produce the best-performing concrete, and the results demonstrated the efficiency and effectiveness of GAs in concrete mixture design. Later, (Jayaram et al., 2009)51 conducted a similar study with the aim of utilizing GA for the design of high-performance concrete, but this time using a larger database of 350 various design mixes. Results proved the effectiveness of GAs in the design and determination of additives ratios for high performance concrete with high fly ash content, while achieving minimal errors in the design proportions. (Kwon et al., 2014)52 developed GA - based optimization models with the goal of determining the optimal concrete mix components for reinforced concrete structures exposed to carbonation attack. Utilizing the GA technique, they generated three simulated concrete mixing ratios for the verification process. These ratios underwent testing in twelve verification cases, yielding favorable results with an average relative error value of 4.6%. Similarly, Yue et al. (2020)53 employed GA to improve the crack resistance of concrete through the optimization of its mix proportions. The developed GA model for demonstrates strong practicality. In a study by Jafari and Mahini (2017)54, GAs were employed as part of a suite of AI techniques based on gene expression programming to achieve optimal designs of lightweight concrete mixes. Utilizing 100 samples, intelligent GA models were constructed showcasing significant accuracy in both achieving optimal design ratios and deriving predictive equations for compressive strength values. recently, a new trend has emerged in several studies that involves integrating the capabilities of GAs with other AI techniques such as ANNs, aiming to maximize their potential in tasks related to prediction and optimization of data55,56. For example, hybrid systems such as (GA-ANN) may entail integrating GAs to optimize the connection weights of neurons within a pre-established ANN to achieve enhanced and superior results compared to using ANN alone.

WCA and GA results

MATLAB code utilizes the WCA and GA to solve a discrete optimization problem. It determines the best combination of modes to minimize an objective function (Fmin). The modes consist of two constants and one function, with 20 options available for each. The algorithm exhaustively searches through 8000 possibilities to find the most effective combination. The input function can be one of 20 different mathematical functions, including trigonometric, logarithmic, exponential, and radical functions. The code also employs 400 different combination functions to enhance the model’s adaptability. The goal is to identify the optimal combination of input constants, input functions, and the inverse form of the combination function. The WCA and GA algorithm are used to search the feasible region and minimize prediction error. Figure 5 presents a graphical representation of the function values (MAE) plotted against the number of iterations for the WCA and GA model. This graph provides a visual depiction of how the MAE values change over the course of the iterations, showing the convergence towards the optimal solution. The algorithm is run for a total of 10 times, and the goal is to identify and report the optimal solution, which corresponds to the lowest MAE. The MAE serves as the objective function, with the aim of minimizing the prediction error. The minimum error with least MAE value of the training data was recorded in the 6th and 3th run with MAE equal to 3.09 and 3.53 for WCA and GA respectively Eqs. (8,9) display the predictive equations for RCS derived using the input data and trained using the WCA and GA. Figure 6 clearly demonstrates that the RCS values predicted by the WCA and GA exhibit a strong agreement with the target experimental results.

Artificial neural networks

ANNs were invented with the aim of emulating the functioning of the human brain. Despite being much simpler and smaller in size compared to the human brain, ANNs possess remarkable capabilities in knowledge and information processing, owing to their resemblance to biological neural networks57. As a result, ANNs have become a powerful tool for various engineering applications. ANNs are particularly effective in capturing and representing the relationships between input and output variables. These networks consist of interconnected neurons and layers, including the input layer, hidden layer(s), and output layer. Neurons within the layers are connected to each other through connection weights58. The input layer receives input data, which is then transmitted to the hidden layer. Within the hidden layer, the weighted input values are aggregated with a bias value added at each neuron. The combined input values are then passed through a transfer function to produce the output value of the neurons. Ultimately, the network model generates its output value through the output layer neurons59.

A three-layered ANN is illustrated in Fig. 7, comprising layers i, j, and k, with corresponding weights Wij and Wjk. In the calibration process, the model’s target variables are compared to the measured outputs. Any errors that arise are then back-propagated through the network. This back-propagation process involves modifying the initially randomly assigned weights and iteratively updating them to minimize the errors. Eventually, the final weights are obtained through this error minimization procedure60. To calculate the input (X) for each neuron in the second and third layers, the weighted sum of outputs from the first layer is computed in Eq. (10). Specifically, the value (y) for a neuron in the second layer, denoted by index (j), is determined using this process.

Subsequently, a nonlinear activation function is applied to (y), resulting in the calculation of the output (f(y)) for each neuron in the second and third layers37. In the present research, the neural networks were constructed using the (Tan-Sigmoid) activation function as defined in Eq. (11).

ANNs have been successfully employed in various construction engineering applications that related to data classification, simulation, and prediction. ANN have been utilized for tasks such as detecting structural damage of the structural elements61, construction engineering management and cost estimation62, modeling material behavior63, prediction of concrete mechanical properties64, and determining concrete mix proportions65. Its worth noting that the developed ANN prediction through this study followed different design criteria than the followed in the earlier designed one. In the earlier literature study published by the current authors18, six neural networks were developed and trained where the average results of them were taken as the overall model’s output. The literature model recorded extremely high overall average R2 value at 0.9877. The main design layouts of the redeveloped ANN model are cleared in the upcoming subsections.

ANN model structure

MATLAB platform (neural network fitting tool) was used to develop the ANN model. Among the various kinds of ANN approaches, this tool uses two-layer feed-forward architecture with tan-sigmoid hidden neurons and linear output neurons as shown in Fig. 8. The limit values of input and output variables used in ANN model are listed in Table 5. One hidden layer with ten neurons (as illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8) was used in the architecture of multilayer neural network due to its minimum mean square error values (MSE) for training, validation, and testing sets. The MATLAB code proceeds to create and train a neural network using the Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation algorithm (trainlm). The data is divided into training, validation, and testing sets using the divideblock method. The default divide ratios for training, validation, and test subsets are 70%, 15% and 15% respectively. To avoid bias arising from the selection of specified samples for training, validation, or testing in neural network model development, the 149 samples were divided and rotated according to the order specified in Table 7. The bias avoidance process led to the creation of five distinct neural networks, representing the main components of the proposed model. The final model output is determined by averaging the outputs of these five neural networks. The neural network fitting tool initially suggested 10 hidden neurons for the network architecture. However, for this study, the constructed five ANNs were trained by varying hidden neurons with only 2 hidden neurons as a starting point. This number was then systematically increased by one each time to assess the network’s performance. By iteratively adjusting the number of hidden neurons, we aimed to identify the optimal configuration that minimized the error.

Neural network results

The performance of Net 1 (as example of the developed nets) is illustrated in Fig. 9, showcasing the expected decrease in error as the network learns. This is a clear sign of successful training. The figure consists of three lines, corresponding to the three datasets used: training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%). The blue line depicts the declining error on the training data, reflecting the network’s internal improvement. The green line represents the validation error, which serves as a gauge of the network’s generalizability. Training is stopped when the validation error ceases to improve, preventing overfitting. As the figure demonstrates, the training error remains lower than the validation error, confirming the absence of overfitting. Prediction errors (residuals) based on the training set inform us about the model’s fit, while those based on the validation set measure the model’s ability to generalize the unseen data (prediction performance). Finally, the red line shows the error on the test data, indicating how well the model generalizes to new data and providing an independent assessment of the network’s performance throughout and beyond training.

Figure 10 visualizes the training process of the selected Net 1 architecture (NN4-12-1) (four input neurons, a single hidden layer having twelve neurons and one output neurons). As shown in Fig. 11, the achieved regression values were 0.99569, 0.9899, and 0.9817 for training, validation, and testing sets, respectively for (NN4-12-1) model. For the best performance of each network, number of hidden neurons and performance measures are presented in Table 8. The RCS values (as the average of the obtained results of the five neural networks) generated by the model were very close to those of experimental counterparts as shown in Fig. 12.

Fuzzy logic concept

FLM are a branch of AI that were initially developed by Lotfi Zadeh in 1965, then it were developed by the years. The fuzzy set theory deals with the complexity and imprecision of data that is often present in real applications, especially those related to the engineering problems66. The concept involves using fuzzy or imprecise terms to represent concepts, allowing the system to efficiently handle unclear or uncertain information. The working principle of fuzzy logic systems relies on a set of logical rules connecting fuzzy variables to make decisions67. This type of AI utilizes fuzzy thinking techniques to represent knowledge and analyze data. In comparison to other AI methods, the distinctive feature lies in its ability to deal with uncertainty and interpret imprecise information more effectively. Fuzzy logic concepts are easy to understand and modify, allowing for adjustments based on real-world conditions. In concrete applications, accurate forecasting of concrete properties represents a significant challenge due to the multitude of influencing factors. FLM provides a flexible framework to model and analyze imprecise data associated with these variables, enabling more reliable predictions68. When it comes to concrete mixtures design which involves various components, FLM excels in handling the vagueness associated with the designed ratios of aggregates, cement, water, and admixtures, allowing for more nuanced approach to mix design69.

Fuzzy logic modeling

As mentioned, FIM are effective tools that leverage fuzzy logic and linguistic fuzzy rules to simulate and model nonlinear data. By applying this to the nature of the data in this study which represents RCS after exposure to high temperatures, the input data values (representing a wide range of four main influencing variables) and the output are interconnected by non-linear relationships that are challenging to model. Due to its proven efficiency and high accuracy in several previous studies related to predicting such relationships70, developing a prediction model using FLM alongside other AI methods employed in the current study makes it a candidate for providing predictions with high regression values. FIS mainly consists of three components: fuzzification, fuzzy rule evaluation, and defuzzification. Fuzzification maps crisp input values to fuzzy sets by a lookup in one or more several membership functions (simple linear functions, such as gauss or triangular ones, are preferable)71, while fuzzy rule evaluation applies linguistic fuzzy rules to determine the relationship between inputs and the output variable. Finally, defuzzification converts the fuzzy output into a crisp value. There are Two primary types of fuzzy rules such as Mamdani and Sugeno. This study employed Sugeno-type fuzzy rules. There are basically two main types of inference operators exist: minimization (min) and product (prod)72. In this study, the prod method was employed because of its better performance. There are many defuzzification methods such as weighted average (wtaver) or weighted sum (wtsum). In Sugeno fuzzy inference systems (FIS), the outputs of fuzzy rules are characterized by crisp function outputs. Mathematically, if F represents a real and continuous mapping within a closed interval, then the parameterized non-linear mapping of a Sugeno-type FIS can be expressed by Eq. (12).

where m denotes number of rules, n defines number of data points, and µA is the membership function of fuzzy set A. Partitioning the input space plays a significant role in determining the effectiveness of the fuzzy inference system. Several approaches, such as grid and tree partitioning, achieve this division, influencing the overall accuracy and interpretability of the system73. For simplicity, it was assumed that FLM had two inputs, x and y, and one output, z. For the zero-order Sugeno-type fuzzy system, typical two rules can be expressed74:

where Ai and Bi are the linguistic labels (low, medium, high, etc.) pi, qi and ri are the parameters set in the consequence function, while z1 and z2 are constants instead of linear Eq. 76. This model utilizes the back-propagation gradient descent algorithm for adaptive learning. This algorithm recursively calculates error signals from the output layer back to the input nodes, similar to the back-propagation learning rule commonly used in feed-forward neural networks75.

Fuzzy logic model layers

FLM system typically consists of 6 layers as shown in Fig. 13, where each serving a specific purpose in the inference process. The input layer distributes the input signals directly to neurons in the next layer without any processing or transformation of input signals. Fuzzification layer is responsible for mapping the input variables to fuzzy sets using membership functions. Each node in this layer calculates the degree of membership of the input to a particular fuzzy set using a membership function. The most common membership functions are Gaussian, triangular, or bell-shaped functions. Each neuron’s output Oi2 is calculated as cleared in Eq. (13).

The fuzzy rule layer involves the formation of fuzzy rules by combining the fuzzy sets from layer 2, called as w in the following Eq. (14). The nodes in this layer compute the RCS of each rule, representing the degree to which the input satisfies the conditions specified by that rule. The RCS is typically calculated using the product (AND) or minimum operation.

The normalization layer normalizes the RCS to ensure that the sum of all RCS is equal to 1. The nodes in this layer adjust the parameters (coefficients) associated with each fuzzy rule. Each node divides the RCS of a rule by the sum of all RCS. and is calculated as in the following Eq. (15).

Defuzzification layer aggregates the results from layer 4 to obtain a crisp output. Depending on the type of system, various methods like the centroid method, mean of maximum (MOM), or other de-fuzzification techniques are employed to obtain a single output value.

where \(\:\stackrel{-}{W}\) is the ith neuron’s output from the previous layer. pi, qi and ri are the parameters set in the consequence function and also the coefficients of linear combination in Sugeno-type fuzzy inference system. Finally, the output layer represents the final output of the FLM model. Each rule’s fuzzy results are transformed into a crisp output in this layer by defuzzification process using the following equations (17).

FL prediction model results

In order to apply for the Sugeno-type FIS in FL system, RCS experimental results were divided into the training, validation and testing groups. Herein, 105 of the experimental data values were used for training dataset, whereas 22 were employed for both the validation and testing datasets. All of the proposed membership functions in this study consist of four inputs and one output as shown in Fig. 14. The limit values of input and output variables used in Sugeno-type fuzzy inference model are listed in Table 5. The training process was prolonged for over 1000 epochs and was halted upon observing the stabilization of error reduction as shown in Fig. 15. For the input variables of the fuzzy controller (RCS), the membership functions in the training dataset were of the triangular type. Additionally, the premise parameter sub-spaces were determined by employing clustering of the training dataset. Thus, 16 rules being obtained as in the following:

Ri: If (Tempreture Degree is in1mf1) and (Exposure Time is in2mf1) and (NAl% is in3mf1) and (NCTs% is in4mf1) then (output is out1mf1) (i = 1, 2,….,16).

Figure 15 displays surface plots illustrating the impact of two variables on the RCS according to the FLM prediction results. Figure 16-a depicts the influence of Time and the percentage of (NCTs) on RCS. In Fig. 16-b, the effects of Time and the percentage of (NAl) on RCS are depicted. Additionally, Fig. 16-c illustrates the impact of Temperature and the percentage of (NAl) on RCS. Figure 17 illustrates the RCS experimental dataset alongside the corresponding predicted values for the training, validation, and testing phases of the FLM model.

3.4. Multiple linear regression

Multiple Regression is a commonly employed method for prediction that has been extensively used for a long time. However, its accuracy and reliability have been found to be unsatisfactory. The limitations of regression models stem from their predetermined structures, which require prior definition. On the other hand, these models are capable of providing an equation based on the input(s) and output(s) of the prediction model76. In this particular study, MLR is employed as a benchmark to compare against novel machine learning methods. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software is utilized to develop the regression equation. The regression technique involves finding the best-fitting line that represents the overall trend of the data, and from there, the equation of the line can be derived. By utilizing data from 149 specimens, the resulting Eq. (18) was obtained as the primary outcome using SPSS.

Comparison of proposed self-adaptive and benchmark models

As mentioned previously, Temperature degrees, exposure durations, NAl and NCTs at different substitution ratios are considered as the input variables with RCS as the model output. The RCS values (22 samples) obtained experimentally were compared to the corresponding testing predicted values from different AI techniques models, as illustrated in Table 9. The statistical analysis in Table 5 demonstrates that the proposed ANN and FLM models accurately predict the RCS values, closely matching the experimental values. Regression analysis is a commonly used statistical technique to assess the influence of predictor variables on a single dependent target variable. It helps analyze the relationship between input and output variables and determine their respective contributions to the relationship After tuning and calibration, the WCA and GA models are compared with ANN, FLM, and MLR models based on performance indicators. The results in Table 10 indicate that the WCA model is the most precise in predicting testing data, followed by the GA model. The performance of ANN and FLM is superior to that of the WCA model. However, it is worth noting that these models do not provide a formulation that relates the input and output data. Additionally, the MLR model is not well-suited for accurately predicting the RCS of the testing data. Figures 18, 19 and 20 display the linear least square fit line, its equation, and the \(\:{R}^{2}\:\)values for the training, validation, and testing datasets for all the AI techniques used. The highest \(\:{R}^{2}\) values are associated with ANN, followed by FLM, WCA, GA, and MLR. These respective values for the training dataset are 0.996, 0.989, 0.929, 0.913, and 0.761. For the validation dataset, they are 0.996, 0.982, 0.982, 0.973, and 0.783. Similarly, for the testing dataset, the \(\:{R}^{2}\) values are 0.968, 0.962, 0.985, 0.974, and 0.815 for ANN, FLM, WCA, GA, and MLR, respectively. Therefore, the results of this analysis align with the findings from other sections of the study, indicating that the accuracy of the WCA model significantly outperforms that of the GA model when compared to the ANN, FLM, and MLR models. The performance of WCA, GA, ANN, FL, and MLR models, was evaluated by comparing their predictions to experimental results for the RCS of concrete after elevated temperature exposure. To conduct this evaluation, data from 7 randomly selected specimens was set aside. The results from this comparison, as presented in Table 11, indicate that WCA, GA, FLM, and ANN demonstrate a high level of accuracy in predicting RCS, outperforming MLR.

Compared to the results of previous studies on predicting the compressive strength of concrete after exposure to high temperatures, as reviewed in Table 2 and the literature review, the linear regression values obtained for the four ML methods are among the highest. However, the most significant contribution of the current study lies in developing nonlinear prediction equations with extremely high regression values, which were developed using WCA and GA techniques. These equations, which appear to be inferred in this nonlinear pattern for the first time in studies predicting the behavior of concrete after exposure to high temperatures are linking the input variables to the outcomes with ease, smoothness, and high accuracy. It is worth noting that as larger databases with more variables become available, more comprehensive and accurate equations can be developed for use in design codes for fire-exposed concrete. The equations derived in the current study remain limited by the boundaries and amount of input used in their construction.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis by ANN weights

In the field of developing ANN research, researchers efforts have been focused on advancing learning rules, enhancing networkss architecture, and exploring new applications for ANNs. However, there has been a lack of sufficient research dedicated to developing fundamental knowledge that allows for a deep understanding of the internal representations generated by ANNs in response to specific problems.Often, ANNs are perceived as black boxes with complex internal workings that transform inputs into desired outputs. Due to the complexity of many ANNs, it is challenging to unravel the intricate mechanisms underlying the network’s weights and the activation values of hidden neurons in relation to the problem at hand. This sets ANNs apart from classical statistical models, as determining the relationship between each explanatory variable and the dependent variable in an ANN is highly complex and non-trivial77. Sensitivity analysis aims to investigate how uncertainties in the output of a mathematical model or system can be attributed to different sources of uncertainty in its inputs. By recalculating outcomes under alternative assumptions, the effect of variables can be determined to provide an efficient method for gaining a deeper understanding of the underlying relationships between input and output variables in a model. In this study, the relative importance of input factors was assessed by examining the importance of weights using the method proposed by (Garson, 1991)78 ,as described in Eq. (19). This approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the significance of weights in determining the relative importance of input factors.

Where IIP is the importance of input parameters, ninput is the number of inputs, nhidden is the number of units and noutput is the number of outputs. The weights in the neural network are crucial parameters that are adjusted during training to optimize the network’s performance and capture underlying patterns in the data. The outcomes obtained from training the (NN4-12-1) model with experimental data are presented in Table 12. For the sensitivity analysis and assessment of weight importance, the training set was used as the data source. Garson’s method was specifically applied to the connection weights within the networks. The impact of each parameter on the RCS value for (NN4-12-1) after exposure to elevated temperatures is visually depicted in Fig. 21. The analysis reveals that the temperature degree and exposure time are the most influential parameters affecting the RCS, followed by the replacement ratios of NAl and NCTs.

Sensitivity analysis with SHAP analysis

The creation of reliable forecasting tools is largely due to ML algorithms’ capability to learn from existing data and predict outcomes in uncharted areas. However, most ML modeling approaches tend to be more complex and less interpretable79. In this study, SHAP method was used to examine the input parameters that lead to accurate prediction of the output RCS data. SHAP goes beyond explaining model behavior, allowing you to pinpoint the individual influence of each input parameter on a specific prediction, with the largest absolute SHAP values highlighting the most influential parameters80. In SHAP analysis, the model predicts the outcomes for each sample, and SHAP values show how much each feature in that sample contributes to the prediction81. MATLAB coodinng was adopted to calculate SHAP values for interpreting the predictions of the developed Artificial ANN model of (NN4-12-1). The developed MATLAB code offers a rich suite of visualization tools for exploring these SHAP values, including mean absolute SHAP values, global explanations, SHAP summary plots, importance bar plots, force plots, and SHAP value heatmaps. Figure 22 clears the obtained SHAP importance values of the scaled RCS predictions. Its follow the same order of the sensitivity analysis calculated via NN weights with different rates. Hierarchical clustering (Fig. 23) is employed in the SHAP Values Heatmap to uncover patterns in feature importance across samples and features. The Force Plot visually represents feature interactions and their effects on predictions for a specific instance as shown in Fig. 24. The SHAP Summary Plot Show the overall impact of features on the model’s predictions across the entire dataset. Feature values are primarily represented using a color code where blue indicates lower feature values and brown indicates higher feature values as indicated in Fig. 25. On the other hand, the f(x) SHAP Values Plot demonstrates feature contributions across different output values as shown in Fig. 26. It is show that the curve aligns with the f(x) values, where an increase in f(x) values leads to an increase in the magnitude of positive SHAP values and a decrease in the magnitude of negative SHAP values if the model leans towards larger predictions.

Limitations and future perspectives

In this section, we discuss the limitations and future perspectives of the study, emphasizing the need for further research in the field. While the focus of this study is on simulating and predicting the RCS of Nano additives-supported concrete under elevated temperatures, it’s acknowledged that the selected four input variables are somewhat limited compared to the myriad factors influencing RCS (as depicted in Table 5). These factors encompass aspects related to concrete design and composition, such as the proportions and types of basic components like cement, aggregate, water, and chemical or mineral admixtures.

Moreover, the study primarily investigates temperature degree and exposure duration, leaving out other pertinent factors like the method of sample cooling post-exposure, effects of fire and flame impingement variations, and sample curing methodology pre-testing. Nonetheless, the developed AI machine learning models successfully model nonlinear relationships between input variables and predict outputs, as demonstrated by the WCA and GA models.

In future studies, leveraging a larger dataset could enable exploration of additional input variables’ influences on RCS. The extensive data capacity of AI models could enhance simulation accuracy and reliability, paving the way for predicting various concrete properties beyond RCS. This includes mechanical properties like tensile and flexural strength, workability, durability, physical properties, and even radiation shielding capabilities, provided relevant data is available. Such advancements could significantly enrich our understanding and application of concrete materials in diverse contexts.

Conclusions

In this study, four prediction and simulation models for Residual Compressive Strength (RCS) of concrete with nano additives post high-temperature exposure were developed using various AI-based machine learning techniques. Alongside, a Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) model was utilized for comparison. The models employing Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Fuzzy Logic Models (FLM), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Water Cycle Algorithm (WCA) showcased remarkable accuracy in prediction and simulation, particularly in deriving precise equations for concrete strength post high-temperature exposure. Notably, the application of WCA in this context is a novel contribution to predicting concrete behavior after such exposure.

Key conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

-

1.

Meta-heuristic algorithms like WCA and GA excel in creating accurate nonlinear equations, offering flexibility and adaptability compared to classical regression methods.

-

2.

AI-based machine learning algorithms demonstrate superior capability in capturing intricate relationships and nonlinear patterns, enhancing reliability in modeling complex systems.

-

3.

While ANN and FLM models perform comparably to WCA and GA, they lack the ability to formulate explicit prediction equations for RCS. Notably, the ANN model outperforms other models in simulating RCS.

-

4.

Equations derived from meta-heuristic algorithms like WCA and GA exhibit high accuracy, serving as robust tools for both researchers and practicing engineers.

-

5.

Sensitivity analysis highlights the highly nonlinear nature of nano concrete under elevated temperatures, emphasizing temperature variations, exposure duration, and nano-additive ratios as significant factors influencing RCS.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khoury, G. A. Effect of fire on concrete and concrete structures. Prog. Struct. Mat. Eng. 2 (4), 429–447 (2000).

Seleem, H. E. H., Rashad, A. M. & Elsokary, T. Effect of elevated temperature on physico-mechanical properties of blended cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (2), 1009–1017 (2011).

Ma, Q., Guo, R., Zhao, Z., Lin, Z. & He, K. Mechanical properties of concrete at high temperature—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 93, 371–383 (2015).

Heikal, M. Effect of elevated temperature on the physico-mechanical and microstructural properties of blended cement pastes. Build. Res. J. 56 (2–3), 157–172 (2008).

Arioz, O. Effects of elevated temperatures on properties of concrete. Fire Saf. J. 42 (8), 516–522 (2007).

Malik, M., Bhattacharyya, S. K. & Barai, S. V. Thermal and mechanical properties of concrete and its constituents at elevated temperatures: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 270, 121398 (2021).

Kodur, V. Properties of concrete at elevated temperatures. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014. (2014).

Elsayd, A. A. & Fathy, I. N. Experimental study of fire effects on compressive strength of normal-strength concrete supported with nanomaterials additives. IOSR J. Mech. Civil Eng. (IOSR-JMCE). 16 (1), 28–37 (2019).

Hertz, K. D. Concrete strength for fire safety design. Magazine Concrete Res. 57 (8), 445–453 (2005).

Netinger, I., Kesegic, I. & Guljas, I. The effect of high temperatures on the mechanical properties of concrete made with different types of aggregates. Fire Saf. J. 46 (7), 425–430 (2011).

Alhamad, A., Yehia, S., Lublóy, É. & Elchalakani, M. Performance of different concrete types exposed to elevated temperatures: a review. Materials. 15 (14), 5032 (2022).

Guler, S., Türkmenoğlu, Z. F. & Ashour, A. Performance of single and hybrid nanoparticles added concrete at ambient and elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 250, 118847 (2020).

Tobbala, D. E., Rashed, A. S., Tayeh, B. A. & Ahmed, T. I. Performance and microstructure analysis of high-strength concrete incorporated with nanoparticles subjected to high temperatures and actual fires. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 22 (2), 85 (2022).

Syamsunur, D., Wei, L., Ahmed Memon, Z., Surol, S. & Md Yusoff, N. I. Concrete performance attenuation of Mix Nano-SiO2 and Nano-CaCO3 under High Temperature. Compr. Rev. Mater. 15 (20), 7073 (2022).

Farzadnia, N., Ali, A. A. A. & Demirboga, R. Characterization of high strength mortars with nano alumina at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 54, 43–54 (2013).

Baloch, W. L., Khushnood, R. A. & Khaliq, W. Influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the residual performance of concrete exposed to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 185, 44–56 (2018).

Sikora, P., Abd Elrahman, M. & Stephan, D. The influence of nanomaterials on the thermal resistance of cement-based composites—a review. Nanomaterials. 8 (7), 465 (2018).

El-Sayed, A. A., Fathy, I. N., Tayeh, B. A. & Almeshal, I. Using artificial neural networks for predicting mechanical and radiation shielding properties of different nano-concretes exposed to elevated temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 324, 126663 (2022).

Das, P. et al. Alkali-activated binder concrete strength prediction using hybrid-deep learning along with shapely additive explanations and uncertainty analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 435, 136711 (2024).

Das, P., Kashem, A., Rahat, J. U. & Karim, R. A Comparative Study of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Recycled Aggregate Concrete and Parametric Analysis1–26 (Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design, 2024).

Karim, R., Islam, M. H., Datta, S. D. & Kashem, A. Synergistic effects of supplementary cementitious materials and compressive strength prediction of concrete using machine learning algorithms with SHAP and PDP analyses. Case Stud. Constr. Mater., 20, e02828. (2024).

Islam, M. M. et al. Prediction of compressive strength of high-performance concrete using optimization machine learning approaches with SHAP analysis. J. Building Pathol. Rehabilitation. 9 (2), 1–20 (2024).

Uysal, M. & Tanyildizi, H. Estimation of compressive strength of self compacting concrete containing polypropylene fiber and mineral additives exposed to high temperature using artificial neural network. Constr. Build. Mater. 27 (1), 404–414 (2012).

Tanyildizi, H. Prediction of the strength properties of carbon fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete exposed to the high temperature using artificial neural network and support vector machine. Adv. Civil Eng. 2018, 1–10 (2018).

Ashteyat, A. M. & Ismeik, M. Predicting residual compressive strength of self-compacted concrete under various temperatures and relative humidity conditions by artificial neural networks. Computers Concrete. 21 (1), 47–54 (2018).

Abbas, H., Al-Salloum, Y. A., Elsanadedy, H. M. & Almusallam, T. H. ANN models for prediction of residual strength of HSC after exposure to elevated temperature. Fire Saf. J. 106, 13–28 (2019).

Ahmad, M., et al. Supervised learning methods for modeling concrete compressive strength prediction at high temperature. Materials. 14(8), 1983 (2021).

Alaskar, A. et al. Comparative Study of Genetic Programming-Based Algorithms for Predicting the Compressive Strength of Concrete at Elevated Temperature (Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2023). e02199.

Alyousef, R. et al. Machine learning-driven predictive models for compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete subjected to high temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02418 (2023).

Kharrazi, H., Toufigh, V. & Boroushaki, M. General and optimal 2D convolutional neural networks to predict the residual compressive strength of concretes exposed to high temperatures. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 131, 107901 (2024).

Farhangi, V., Moradi, M. J., Daneshvar, K. & Hajiloo, H. Application of artificial intelligence in predicting the residual mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) after high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134609 (2024).

Gupta, T., Patel, K. A., Siddique, S., Sharma, R. K. & Chaudhary, S. Prediction of mechanical properties of rubberised concrete exposed to elevated temperature using ANN. Measurement. 147, 106870 (2019).

Akbari, M. & Jafari Deligani, V. Data driven models for compressive strength prediction of concrete at high temperatures. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 14, 311–321 (2020).

Al-Zwainy, F. M., Salih, S. A. & Aldikheeli, M. R. Prediction of residual strength of sustainable self-consolidating concrete exposed to elevated temperature using artificial intelligent technique. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 18 (2), 1–15 (2021).

Adamu, M., Rehman, K. U., Ibrahim, Y. E. & Shatanawi, W. Predicting the strengths of date fiber reinforced concrete subjected to elevated temperature using artificial neural network, and Weibull distribution. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 18649 (2023).

Ahmad, M., et al. Supervised learning methods for modeling concrete compressive strength prediction at high temperature. Materials 14(8), 1983 (2021).

Chen, H., Yang, J. & Chen, X. A convolution-based deep learning approach for estimating compressive strength of fiber reinforced concrete at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 313, 125437 (2021).

Naseri, H., Jahanbakhsh, H., Moghadas Nejad, F. & Golroo, A. Developing a novel machine learning method to predict the compressive strength of fly ash concrete in different ages. AUT J. Civil Eng. 4 (4), 423–436 (2020).

Naseri, H., Jahanbakhsh, H., Hosseini, P. & Nejad, F. M. Designing sustainable concrete mixture by developing a new machine learning technique. J. Clean. Prod. 258, 120578 (2020).

Sobhani, J., Najimi, M., Pourkhorshidi, A. R. & Parhizkar, T. Prediction of the compressive strength of no-slump concrete: a comparative study of regression, neural network and ANFIS models. Constr. Build. Mater. 24 (5), 709–718 (2010).

Abduljabbar, R., Dia, H., Liyanage, S. & Bagloee, S. A. Applications of artificial intelligence in transport: an overview. Sustainability. 11 (1), 189 (2019).

Eskandar, H., Sadollah, A., Bahreininejad, A. & Hamdi, M. Water cycle algorithm–A novel metaheuristic optimization method for solving constrained engineering optimization problems. Comput. Struct. 110, 151–166 (2012).

Nasir, M., Sadollah, A., Choi, Y. H. & Kim, J. H. A comprehensive review on water cycle algorithm and its applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 17433–17488 (2020).

Sadollah, A., Eskandar, H., Bahreininejad, A. & Kim, J. H. Water cycle algorithm with evaporation rate for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 30, 58–71 (2015).

Ashrafian, A., Shokri, F., Amiri, M. J. T., Yaseen, Z. M. & Rezaie-Balf, M. Compressive strength of Foamed Cellular Lightweight concrete simulation: new development of hybrid artificial intelligence model. Constr. Build. Mater. 230, 117048 (2020).

Naseri, H. et al. A novel evolutionary learning to prepare sustainable concrete mixtures with supplementary cementitious materials. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25 (7), 5831–5865 (2023).

Moayedi, H. et al. Optimized ANNs for predicting compressive strength of high-performance concrete. Steel Compos. Struct. 44, 853–868 (2022).

Pandey, H. M., Chaudhary, A. & Mehrotra, D. A comparative review of approaches to prevent premature convergence in GA. Appl. Soft Comput. 24, 1047–1077 (2014).

Nunez, I., Marani, A., Flah, M. & Nehdi, M. L. Estimating compressive strength of modern concrete mixtures using computational intelligence: a systematic review. Constr. Build. Mater. 310, 125279 (2021).

Lim, C. H., Yoon, Y. S. & Kim, J. H. Genetic algorithm in mix proportioning of high-performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 34 (3), 409–420 (2004).

Jayaram, M. A., Nataraja, M. C. & Ravikumar, C. N. Elitist genetic algorithm models: optimization of high performance concrete mixes. Mater. Manuf. Processes. 24 (2), 225–229 (2009).

Kwon, S. J., Lee, B. J. & Kim, Y. Y. Concrete mix design for service life of RC structures under carbonation using genetic algorithm. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014. (2014).

Yue, L., Hongwen, L., Yinuo, L. & Caiyun, J. Optimum design of high-strength concrete mix proportion for crack resistance using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithm. Front. Mater. 7, 590661 (2020).

Jafari, S. & Mahini, S. S. Lightweight concrete design using gene expression programing. Constr. Build. Mater. 139, 93–100 (2017).

Chandwani, V., Agrawal, V. & Nagar, R. Modeling slump of ready mix concrete using genetic algorithms assisted training of Artificial neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 42 (2), 885–893 (2015).

Rebouh, R., Boukhatem, B., Ghrici, M. & Tagnit-Hamou, A. A practical hybrid NNGA system for predicting the compressive strength of concrete containing natural pozzolan using an evolutionary structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 149, 778–789 (2017).

Kriegeskorte, N. Deep neural networks: a new framework for modeling biological vision and brain information processing. Annual Rev. Vis. Sci. 1, 417–446 (2015).

Park, Y. S. & Lek, S. Artificial neural networks: multilayer perceptron for ecological modeling. In Developments in Environmental Modelling (Vol. 28, 123–140). Elsevier. (2016).

Hassan-Esfahani, L., Torres-Rua, A., Jensen, A. & McKee, M. Assessment of surface soil moisture using high-resolution multi-spectral imagery and artificial neural networks. Remote Sens. 7 (3), 2627–2646 (2015).

Cao, W., Wang, X., Ming, Z. & Gao, J. A review on neural networks with random weights. Neurocomputing. 275, 278–287 (2018).

Gordan, M. et al. A hybrid ANN-based imperial competitive algorithm methodology for structural damage identification of slab-on-girder bridge using data mining. Appl. Soft Comput. 88, 106013 (2020).

Wang, Y. R., Yu, C. Y. & Chan, H. H. Predicting construction cost and schedule success using artificial neural networks ensemble and support vector machines classification models. Int. J. Project Manage. 30 (4), 470–478 (2012).

Baldo, N., Manthos, E. & Pasetto, M. Analysis of the mechanical behaviour of asphalt concretes using artificial neural networks. Adv. Civil Eng. 2018. (2018).

Yoon, J. Y., Kim, H., Lee, Y. J. & Sim, S. H. Prediction model for mechanical properties of lightweight aggregate concrete using artificial neural network. Materials. 12 (17), 2678 (2019).

Açikgenç, M., Ulaş, M. & Alyamaç, K. E. Using an artificial neural network to predict mix compositions of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 40, 407–419 (2015).

Wang, H., Xu, Z. & Pedrycz, W. An overview on the roles of fuzzy set techniques in big data processing: Trends, challenges and opportunities. Knowl. Based Syst. 118, 15–30 (2017).

Dumitrescu, C., Ciotirnae, P. & Vizitiu, C. Fuzzy logic for intelligent control system using soft computing applications. Sensors. 21 (8), 2617 (2021).

Fathy, I. N., El-Sayed, A. A. & Sufe, W. H. Predicting gamma ray linear attenuation coefficient for different nano-concrete types using artificial intelligence. Fayoum Univ. J. Eng. 4 (1), 176–190 (2021).

Ghoddousi, P., Shirzadi Javid, A. A. & Sobhani, J. A fuzzy system methodology for concrete mixture design considering maximum packing density and minimum cement content. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 40, 2239–2249 (2015).

Chaabene, W. B., Flah, M. & Nehdi, M. L. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties of concrete: critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 260, 119889 (2020).

Demir, F. A new way of prediction elastic modulus of normal and high strength concrete—fuzzy logic. Cem. Concr. Res. 35 (8), 1531–1538 (2005).