Abstract

The cementation of desert aeolian sand is a key method to control land desertification and dust storms, so an economical, green and durable process to reach the binding between sand grains needs to be searched. The method based on the microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) appeared in recent years as a promising process that proved its efficiency. The feasibility of the MICP technique to treat aeolian sand composed by low clay content, fine particles, low water content and characterized by weak permeability was demonstrated in the present paper. The effects of initial dry density, cementation number and curing time on the permeability and strength of MICP-treated aeolian sand were investigated using permeability tests and unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests. The microstructure of aeolian sand was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) tests and X-ray diffraction (XRD), aiming to reveal the solidification principle of MICP. The tests result indicated that when the initial dry density and the cementation number rose, the hydraulic conductivity of aeolian sand decreased while the mechanical strength given by UCS values improved. When the initial dry density was 1.65 g/cm3, the curing time was 3 h and the cementation number reached 20, the hydraulic conductivity and UCS reached 0.00151 cm/s and 1050.30 kPa, respectively. With increasing curing time, the hydraulic conductivity first decreased, followed by an increase, while the UCS exhibited an up and then a downtrend. Furthermore, the correlation between UCS values and the CaCO3 content reached a high R2 value equal to 0.912, which confirmed that the cementation occurred in sandy material and governed the soil strengthening. Indeed, the calcium carbonate crystals observed by SEM and XRD enhanced the friction between particles when they wrapped around the sand grains surface, while carbonates reduced the soil permeability when filling the pores and sticking the sand particles together. Finally, the theoretical and scientific knowledge brought by the present study should help in managing sand in desert areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land desertification accelerates the deterioration of the ecological environment, leading to vegetation destruction, soil erosion, arable land reduction, and dust storm outbreaks, which seriously restricts the rapid development of the economy1. Therefore, the way to effectively restrain land desertification is a current hot topic of research in the field of ecological protection. Under the extremely dry and semi-dry conditions of desert zones, the aeolian sand composed by low clay content, and fine particles, is characterized by low water content and weak permeability, and the flowing of aeolian sand under environmental changes and human activities is the main cause of land desertification. Currently, the traditional methods for sand cementation can be divided into engineering methods, the chemical ones and the methods based on vegetation. But such methods have disadvantages of cumbersome construction, high maintenance cost and weak durability2,3,4. Among them, the resulting material from the engineering sand fixation method is prone to being buried by quicksand and the method is often used as a temporary and auxiliary sand fixation method. The chemical sand fixation method has poor compatibility with desert environments and is prone to produce side effect with secondary pollution. Finally, the vegetation sand fixation method is greatly influenced by climate and season. So, the microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) and enzyme-induced calcite precipitation (EICP) techniques offered new opportunities to treat sandy material and produce soil stabilization, by involving calcium carbonate precipitation through a biochemical reaction catalyzed by urease enzymes obtained from bacteria cells or plants5,6,7,8,9,10. An increase of the soil mechanical strength after such process occurred as well as a reduction of seepage by rapid consolidation of the soil grains into units11,12,13.Unlike conventional methods, MICP and EICP techniques are environmentally friendly and sustainable. Both methods have significant potential for many scientific and engineering applications including a soil strength improvement, a decrease of soil liquefaction potential, the control of soil surface erosion, the reducing permeability, and a way to remediate soil from heavy metal contamination14,15,16,17. In EICP method, the cost of enzymes remains high18 and the EICP process lacks nucleation points, which may not effectively bind soil particles. The MICP technology can compensate for the shortcomings of EICP technology with microorganisms attached to soil particles, that provide effective nucleation sites for mineral precipitation, thereby enhancing the morphology of precipitated poly crystals and improving the strength and stability of the treated soil.

Among literature dealing with the MICP researches, several authors brought evidences on MICP efficiency. Pakbaz et al.19 concluded that the UCS of samples treated by aerobic bacteria was 22–73% higher than the ones of soil cemented by anaerobic bacteria, and the UCS of the test pieces improved by 156–270% compared with that of untreated samples. Liang et al.20 analysed also the impact of fibres on the strength of MICP-treated sand. According to the results, the treated sand showed first the UCS rise and then a collapse with increasing fibres length, whose optimum length for polypropylene fibres and basalt fibres was 9 and 12 mm, respectively. Wang et al.21 reported that the combination of calcium carbonate crystal filling from the MICP process and extracellular polysaccharide bonding (polysaccharides come from plant and are the most abundant natural biopolymer) enhanced the strength and ductility of sand columns. Imran et al.22 noted also that the addition of fiber (jute) improved the durability of the MICP-treated samples by more than 50%, and the wet-dry cyclic operation alter its mechanical properties. Zhao et al.23 noted that the failure strain and ductility of MICP-treated calcareous sand were improved when using fibers. The optimum contents of glass fiber and polyester fiber were 0.20% and 0.25%, respectively. Tangential flow-induced interface erosion poses a major threat to a wide variety of engineering structures. Saracho et al.24 used a flow velocity measurement method to measure the erosion characteristics of fine sand and tests were conducted using a newly designed erosion function apparatus (EFA). The results showed that MICP-treated sand eroded under a block form, while untreated samples exhibited erosion by particles and piece of material departure. All previous results indicate that effective contact between fiber and sand particles can improve the failure strain, ductility, and strength of specimens. However, fiber-solidified sand has problems such as uneven fiber distribution and unclear toughening mechanism in the practical engineering. Furthermore, the CaCO3 content and the concentration of the binding treatment solution also affected the erosion rate.

Wu et al.25 showed also that the MICP-treated sand exhibited significantly greater dilatancy in comparison to uncemented sand characterized by similar density, and the higher dilatancy was attributed to a higher shear strength, resulting from a greater effective cohesion. Lai et al.26 found that under low-pH bacterial solution conditions, the consolidation of iron tailing sand by the MICP method is more efficient than the one of usual sand. Indeed, the low-pH bacterial solution can lead to a higher quantities of CaCO3 precipitates and to a longer bioflocculation generation time. In addition, due to the existence of CaO in iron tailing sand, a better cementation effect was obtained compared to usual quartz sand.

Researchers conducted also experiments more specifically on MICP-treated aeolian sand: based on the scanning electron microscope (SEM) testing results, Gao et al.27 found that numerous pores were generated in calcium carbonate after long-term ultraviolet degradation (UV-degradation), which proved that the property of calcium carbonate was weakened. Ming et al.28 studied the impact of different calcium sources on the mechanical strength developed by aeolian sand treated with MICP. The calcium chloride produced a higher content of calcite crystals between sand particles, while the calcium acetate produced calcite crystals with irregular shapes and smaller particles, resulting in low mechanical strength and hydraulic conductivity.

Furthermore, Li et al.29 observed that the MICP-mineralized overlay (forming a crust on desert sand) started to form by 4 days in the field test and the overlay showed stable mechanical strength and thickness by 7 days. The bio-mineralized overlay crust had an average thickness of approximately 2.0–2.5 cm. Li et al.3 discovered also that CaCO3 occupied the gaps among the aeolian sand particles, which induces a lowering of pore volume. With increasing concentration of the treatment solution, the levels of CaCO3 and UCS went up while the permeability went down. In complement, Tian et al.30,31 showed that MICP has a good effect on preventing wind erosion occurring in aeolian sand, considering that UCS reached 14.01 MPa after treatment while the hydraulic conductivity was significantly reduced compared with the untreated soil. However, the uniformity of the sample was greatly affected by the injection rate of the treatment solution. The CaCO3 crystal produced between sand particles were calcite, with polyhedral/spherical form, accompanied by inflorescence occurrence on sample surface. Considering the wind tunnel tests applied by Dubey et al.32, the MICP-cured aeolian sand samples showed UCS around 1 MPa with a CaCO3 content close to 1.3% after a 0.5 M consolidation solution treatment. After a 1 M treatment, the maximum wind speed that prevents soil from wind effect exceeded 55 km/h, suggesting that bio-consolidation can significantly enhance erosion resistance. In agreement with previous results, Devrani et al.33 stated that the threshold friction velocity of aeolian sand increased from 20 km/h to 45 km/h following MICP treatment and the urea-CaCl2 concentration played a crucial role in the aeolian sand cementation.

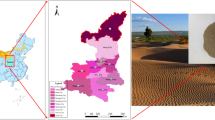

Considering results in literature, the few papers on the solidification of aeolian sand using the MICP process used to fight against the harmful phenomenon induced by uncemented sand particles in desert areas, needs to be completed. If the mechanical properties of the MICP treated aeolian sand through unconfined compressive strength tests (UCS) is mainly described, the permeability test on such material after treatment remains little described. In the present study, the tested aeolian sand came from the Maowusu Desert in Yulin City, Shaanxi Province and the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and permeability tests allowed to discuss the effects of initial dry density, cementation number(corresponding to the number of the cementing solution injection), and curing time on the efficiency of aeolian sand treatment. In complement, the mechanism of MICP solidification of aeolian sand was analyzed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) to observe the shape and size of particles precipitated between sand particles and to compare them to the various microstructures described in literature.

Materials and methods

Test materials

The tested aeolian sand in the study came from Maowusu Desert, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province, China. According to the Soil Test Method Standard (GB/T 50123 − 2019)34, the tested sand was classified as poorly graded fine sand. Table 1 shows the physical properties of aeolian sands.

For MICP treatment, the Bacillus pasteurii (ATCC 11859) was purchased from the Shanghai Bioresource Collection Centre in China. Urea (AR, purity 99.7%) was purchased from Tianjin Hengxing Chemical Reagent Manufacturing Co., Ltd. in China, and anhydrous calcium chloride (AR, purity 99.7%) was purchased from China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. in China. Figure 1 showed the bacterial culture process. The bacterial culture medium corresponded to 15 g tryptone, 5 g peptone, 5 g sodium chloride mixed with 900 mL distilled water and 100 mL 20% urea. Previous mixture was (1:1) diluted in 90 mL of distilled water, and the solution pH was adjusted to 9 by adding NaOH solution. After that, the substance was sterilized using high-pressure steam at 121℃ for 15 min. After cooling down to 60℃, the mixture was poured into 10 mL of water containing 20% urea, which had been filtered and sterilized (step I). The culture medium with Bacillus pasteurii bacterial was then incubated at 30℃ on a shaker at a shaking frequency of 200 rpm. The bacterial culture was stopped when the OD600 reached 1.0, and reserved at 4℃ for future use (step II). After the step II, 1mL bacterial solution (OD600 = 1.0) was inoculated into the culture medium (step I) followed by on a 200 rpm shaking at 30℃ until the OD600 reached 1.5 (step III). The final bacterial solution (solution 1, and OD600 = 1.5) was produced and used for injection in soil.

For sand consolidation, the cementing solution (solution 2) consisted of a (1:1 in volume) combination of 1 M CaCl2 and 1 M urea prepared in parallel to the bacterial solution. The solution 1 which was produced in the step III was used to inject in soil.

Sample preparation and experimental setup

The Fig. 2 shows the experimental setup containing the soil specimen that is submitted to MICP treatment.

Aperspex tubes with a 150 mm height and a 39.1 mm diameter was used as a mold to contain the tested soil specimen. The mold is split into two parts for easy soil removal (both parts are fixed with hot melt adhesive). The tested samples of aeolian sand in the mold were 80 mm in height and 39.1 mm in diameter. A thin plastic film was placed around the sample to prevent lateral leakage. To fill the mold, the sand was first sieved to pass through a 0.5 mm sieve. Then after weighing of the sand quantity required to reach the targeted initial dry density (listed in the program design in Table 2. The sample was prepared in 4 layers in the mold and each layer was compacted to 20 cm using a sample controller. Three layers of filter paper were positioned beneath the sample prior to filling, whilst an additional layer was situated on top of the sample to prevent any particles departure during the treatment by solutions injection. The top and bottom ends of the mold were closed off with rubber plugs that had openings in them. The pre-existing aperture was linked to the liquid inlet and outlet and a peristaltic pump acts as an injection device for both the bacterial and cementing solution. As shown in Fig. 2, the bacteria solution and cementing solution were injected separately.

Testing program

To investigate the influence of initial dry density, cementation number and curing time on the strength and permeability properties of aeolian sand, a experimental program was applied as described in Table 2.

For aeolian sand solidification, the bacterial solution (solution 1) and the cementing solution (solution 2) were alternatively injected from the top to the bottom of the sand sample35,36, which can utilize the gravity effect to allow solutions to permeate into the sample and ensure the most complete reaction. According to the microbial growth characteristic of the logarithmic period and stable period36, the appropriate curing time was sought to achieve the best effect for sand consolidation. The bacterial number represents the total number of times when bacterial solutions was injected. The cementation number represents the number of times that the cementing solution was injected. The curing time refers to the duration for the bacterial solution infiltration before the injection of the cementing solution. The injection sequence describes the injection number of bacterial solution followed by the injection of cementing solution. The step wise infusion method was used in the experiments, and the infusion of cementing solution standing for a curing time after the infusion of bacteria solution. The bacterial solution (40 mL) was injected into the sand and stood for a period of time (1 h, 3 h, or 5 h), and then the cementing solution (40 mL) was injected into the sand at 12-hours intervals.

After injection test, the samples were washed 3 times with 100 ml deionized water to end the MICP reaction and oven-dried at 80 °C for 48 h.

After extraction of the sand specimen from the mold, the permeability and the UCS test were carried out on MICP-treated aeolian sand by the Standard for Soil Test Method (GB/T 50123 − 2019). Permeability testing was carried out using a variable water head method. The UCS testing used a soil triaxial instrument (KTL-LDF 50 type, Xi’an KTL Instruments Co., Ltd, Xi’an, China). The UCS test was loaded at 1% per minute and stopped when reaching15% axial strain. The acid washing method is used in the experiment to determine the amount of calcium carbonate generated and the weight difference before and after acid washing is the content of calcium carbonate37. In the experiment, each group of tests was repeated twice. For data obtained from two experiments, it consisted to eliminate one unreasonable value and to keep the reasonable one as the final value.

Results and discussion

Effect of initial dry density on the permeability and strength properties

The hydraulic conductivity versus initial dry density curves at 1, 3 and 5 h curing times are shown in Fig. 3.

As expected, the hydraulic conductivity of the MICP-treated specimen dropped as the initial dry density increased38.

When the curing time was 3 h and the cementation number reached 20, the k of the MICP-treated samples with initial dry densities of 1.45 g/cm3, 1.55 g/cm3, and 1.65 g/cm3 reached 0.00456 cm/s, 0.00270 cm/s, and 0.00151 cm/s, respectively. Under the same condition for the MICP treatment, when the initial dry density became 1.65 g/cm3, the k decreased by 66.9% and 44.1%, respectively, compared to k with initial dry densities of 1.45 g/cm3 and 1.55 g/cm3. At a constant curing time, the hydraulic conductivity decreased with an increase in the cementation number. The hydraulic conductivity reached 0.0071 cm/s under the conditions of 1.45 g/cm3 initial dry density, 12 cementation number, and 1 h curing time, and the hydraulic conductivity decreased until 0.0017 cm/s under the conditions of 1.65 g/cm3 initial dry density, 20 cementation number, and 1 h curing time. The key reason for this phenomenon is that the sand particles were in close contact under high dry density, and the CaCO3 produced from the MICP process could effectively cement the sand particles and block the infiltration pathways, thereby leading to decreased hydraulic conductivity. As the cementation number increased, the bacterial solution and cementing solution reacted more and more to produce increasing number of CaCO3 crystals that cover the sand particles or fill the spaces between sand gains, which induce a blockage of the specimen drainage and reduce its permeability.

The Fig. 4 shows the UCS measurements versus specimen initial dry density at the curing time of 1, 3 and 5 h, respectively.

The UCS of the cemented sample after MICP treatment rose as the initial dry density increased, and the UCS increased with increasing cementation number when curing time kept constant. The UCS reached 121.6 kPa under the conditions of 1.45 g/cm3 initial dry density, 12 cementation number, and 1 h curing time. With an initial dry density of 1.65 g/cm3, a cementation number of 20 and a curing time of 1 h, the UCS reached 925.8 kPa. When the curing time was 3 h and the cementation number was 20, the initial dry density change from 1.45 g/cm3 to 1.65 g/cm3, and the UCS increased from 534.22 kPa to 1050.30 kPa, which improved by 96.6%. Results demonstrated that the CaCO3 crystals could effectively bind the sand particles under a large range of initial dry density. Compared to the loose aeolian sand (low initial density), the cohesion and frictional forces of cemented sand should increase when subject to external stress, which results in the improvement of strength as observed by Tasuji et al.39.

Effect of the cementation number on the permeability and strength properties

Figure 5 displays the hydraulic conductivity curves compared to the cementation number after curing for 1, 3, and 5 h. The hydraulic conductivity decreased as the cementation number increased, indicating that the cementation effect of aeolian sand increased with the increase of the cementation number. Furthermore, as the initial dry density increased, the hydraulic conductivity dropped when the curing time remained constant.

Figure 6 displays the plots of UCS about the cementation number at curing time of 1, 3 and 5 h, respectively. The results show an increase in UCS with an increase in cementation number, which exhibited an opposite tendency to the hydraulic conductivity. When the curing time was kept constant, the UCS rose with increasing initial dry density. The level of reaction between the bacterial solution and the cementing solution in the MICP process determined the strengthening impact of the aeolian sand. Under a large cementation number (20), the bacterial solution reacted fully with the cementing solution to produce more CaCO3 crystals. The CaCO3 crystals fill the pores of sand particles, reducing the hydraulic conductivity and increasing the UCS.

Effect of curing time on the permeability and strength properties

The duration between bacterial solution and cementing solution during the MICP process significantly influences the form of CaCO3 crystals. Figure 7 illustrates the hydraulic conductivity curves plotted against the curing time for the initial dry densities of 1.45 g/cm3, 1.55 g/cm3, and 1.65 g/cm3, respectively.

The hydraulic conductivity of the MICP-treated aeolian sand decreased and then increased with longer curing time. When the initial dry density was kept constant, the hydraulic conductivity dropped as the cementation number rose. Figure 8 displays the UCS curves against curing time, respectively, for initial dry densities of 1.45, 1.55, and 1.65 g/cm3. The UCS of aeolian sand demonstrated an initial increase, followed by a fall with increasing curing time. The UCS gradually raised as the cementation number increased for the same initial dry density. The key reason for this phenomenon is that the bacterial solution was first injected during the experiment, and the bacterial solution infiltrated along the sand column from top to bottom under the gravity effect, attached slowly to the sand surface. Due to the size of the bacteria themselves (0.5–3 μm)40, it takes more time for them to penetrate into the sand column and spread evenly over the sand surface. After a preset curing time, the cementing solution was injected and reacted with the bacterial solution to cement the sand particles by precipitating some CaCO3 crystals. From the experimental results, it can be seen that the bacterial solution had less contact with sand particles, and the MICP mineralization reaction produced less CaCO3 which induce low sand mechanical strength when the curing time was 1 h. When the curing time was 3 h, the MICP mineralization reaction produced a large amount of CaCO3 that combined with sand particles, resulting in higher mechanical strength. After 5 h curing time, the bacterial solution flowed out from the sand from top to bottom, resulting in a decrease in sand mechanical strength.

UCS versus CaCO3 content

Figure 9 displays the relationships between the initial dry density and cementation number.

The dry density of the specimens rose progressively with increasing cementation number which is in agreement with the Liu et al.’s results38. The analysis suggests that the CaCO3 crystals formed during the MICP process filled the pores between sand particles, leading to an increase in the initial dry density. When the cementation number remained unchanged, the dry density increased as the initial dry density rose. This indicates that a large initial dry density is beneficial to generate CaCO3 crystals.

To go further, Fig. 10 shows the curves of UCS versus CaCO3 content.

An increasing CaCO3 content enhanced the specimen UCS, resulting in a coefficient of determination equal to 0.912. Such good relationship between UCS and CaCO3 content was also observed by Liu et al.’sresults38. Calcium carbonate crystals served as both a filler and bonding agent for sand grains, ultimately resulting in heightened cohesion, friction, and compressive strength. Thus, a noteworthy correlation existed between the CaCO3 level and UCS of solidified aeolian sand.

Cementation mechanism in MICP-treated aeolian sand

To compare the mineral composition of aeolian sand before and after solidification, and evaluate the effect of MICP solidification reaction on aeolian sand, the crystal phase of the sample was determined through XRD testing. Figure 11 shows the XRD pattern of loose aeolian sand and MICP-solidified aeolian sand. According to the analysis conducted the software Jade 6 (TiLab, Beijing, China), the mineral composition was mainly quartz for loose aeolian sand samples. Characteristic diffraction peaks of calcite appeared as expected on the XRD pattern of aeolian sand treated with MICP, the intensity was achieved 4930 when the scanning angle was 26.7°, with some other peaks with low intensity.

As expected, the observations allowed explaining the strengthening of MICP-cemented caused by the CaCO3 development during the urea/urease reaction. However the literature mentioned that the strength was dependent on the distribution form of the CaCO3 crystals (crystal size, shape and organization, aggregation rate inducing a porous binding matrix). According to the distribution relationship between CaCO3 crystals and sand particles, the cementation modes were usually divided into three types41: namely coverage, contact, and cementation. The CaCO3 crystals generated during the MICP process are mainly classified into calcite, aragonite and vaterite42. The studies found that Ca2+ concentration can affect bacterial metabolism and subsequent enzymatic reactions, thereby affecting the crystal form and morphology of CaCO344. Low bacterial activity can lead to insufficient enzymatic reactions, preventing the complete transformation of vaterite into calcite, resulting in the coexistence of both calcite and vaterite crystal structures43.

In Fig. 12(a), CaCO3 crystals are covered the sand surfaces so the cementation modes of CaCO3 crystals precipitation was the coverage. The bacteria were first adsorbed onto the surface of sand particles during the MICP process and provided nucleation sites for CaCO3 generated. Subsequently, the CaCO3 accumulated around the bacteria and deposited on the sand surfaces44. So coverage type can reduce the permeability of aeolian sand to some extent but has limited effect on enhancing the strength. However, as the MICP mineralization reaction proceeded, a large amount of Ca2+ in the cementing solution was reacted with CO32− produced by urea hydrolysis to form CaCO3, which gradually enveloped microbial, causing bacterial death resulting from hypoxia and ultimately stopping urease production. Furthermore, urease gradually loses its activity and reduced production of CaCO345.

As shown in Fig. 12(b), CaCO3 crystals filled the sand pores, and the contact form changed from no-contact to point-contact. With the development of the MICP process, the sand particles in the pores were stacked more densely, resulting in a reduction in permeability and some improvement in strength. Figure 12(c) shows that the CaCO3 crystals held the sand particles together, and the contact form converted from point-contact to surface-contact, enhancing surface roughness and occlusion of sand particles. With the increase of the cohesion and friction between sand particles, aeolian sand strength increased. Based on XRD test result, the CaCO3 crystals with a prismatic microscopic morphology in the Fig. 12(d), signified the predominance of calcite-type among carbonates but other crystal shape could be observed such as schist morphology. However, the stability of calcite appears usually significantly far exceeding the one of aragonite and vaterite46. Therefore, mainly calcite crystals effectively bonded sand particles to improve their strength.

Furthermore the Fig. 12 (e) and (f) show respectively SEM images of MICP-treated aeolian sand with cementation numbers of 16 and 20, when the initial dry density was 1.65 g/cm3 and the curing time was 3 h. When the cementation number was 16, the CaCO3 cementation modes were mainly contact with few coverage. The CaCO3 mostly covered the sand particle surface, increasing particle volume and surface area, and decreasing the contact between particles. The CaCO3 generated by the MICP mineralization reaction filled the sand particles, resulting in a decrease in permeability and an increase in strength. When the cementation number was 20, the MICP mineralization reaction generated a large amount of CaCO3. The main cementation modes of CaCO3 were cementation followed by contact type. The CaCO3 deposited, aggregated and grew between non-contacting sand particles until the particles were bonded together by the physical interaction of precipitated particles. With the development of the MICP process, the sand particles in the pores were stacked more densely, resulting in a reduction in permeability and a significant increase in strength.

Conclusions

Complementary to the usual UCS testing, the permeability of MICP-treated sand specimen was assessed in order to confirm the treatment efficiency for wind erosion control. In order to optimize treatment, the impact of the curing time, the cementation number and initial dry density of sandy specimen on the hydraulic conductivity and the UCS were analysed conducting to the establishment of a relationship between UCS and precipitated CaCO3 concentration content. The mechanism of MICP solidification of aeolian sand was analyzed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

As the initial dry density increased, the hydraulic conductivity of solidified sand decreased, whereas the UCS increased. When the curing time was kept constant, the hydraulic conductivity decreased and the UCS increased as the cementation number increased. When the initial dry density was 1.65 g/cm3, the curing time was 3 h and the cementation number reached 20, the hydraulic conductivity and UCS reached 0.00151 cm/s and 1050.30 kPa, respectively.

-

(2)

With increasing of cementation number, the hydraulic conductivity decreased, while the UCS increased. At constant curing time, the hydraulic conductivity decreased and UCS improved with rising initial dry density.

-

(3)

With increasing curing time, the hydraulic conductivity first dropped and then rose, while the unconfined compressive strength first rose and then fell. When the initial dry density was kept constant, the hydraulic conductivity decreased and UCS increased with increasing of cementation number.

-

(4)

The UCS reached 1050.30 kPa under the conditions of initial dry density was 1.65 g/cm3, the cementation number was 20, and the curing time was 3 h, which was the optimized condition to obtain cementation in MICP-treated aeolian sand.

-

(5)

The initial dry density of the specimens increased progressively with the rise in cementation number. With increasing CaCO3 generation, the UCS increased following a trend with a high determination coefficient (reaching 0.912).

-

(6)

When CaCO3 crystals wrapped on the sand surfaces, the permeability of aeolian sand decreased. When CaCO3 crystals filled the pores between sand particles, the permeability reduced and the strength improved. When CaCO3 crystals bonded sand particles into a whole, the cohesion and friction were increased, resulting in the strength improvement in aeolian sand.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published paper. The detailed data could be supplied on demand after corresponding author.

References

Xu, D. Y., You, X. G. & Xia, C. L. Assessing the spatial-temporal pattern and evolution of areas sensitive to land desertification in North China. Ecol. Indic.97, 150–158 (2019).

Zhang, Z. H. & Huisingh, D. Combating desertification in China: monitoring, control, management and revegetation. J. Clean. Prod.182, 765–775 (2018).

Li, Z. H. et al. Synergistic effect of cyanobacteria and nano-sand-stabilizer on biocrust formation and sand fixation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.9, 104887 (2021).

Lababpour, A. Potentials of the microalgae inoculant in restoration of biological soil crusts to combat desertification. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.13, 2521–2532 (2016).

Li, M. D. et al. Influence of fiber addition on mechanical properties of MICP-treated sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.28, 04015166 (2016).

Li, M. D., Lin, L. & Zhang, Z. D. Review, outlook and application technology design on soil improvement by microbial induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Chi Civ. Eng. J.49, 80–87 (2016).

Fan, W. J. et al. Comparison of bioaugmentation and biostimulation approaches for biocementation in soil column experiments. J. Build. Eng.82, 108335 (2024).

Miao, L. C., Wang, H. X., Sun, X. H., Wu, L. Y. & Fan, G. C. Effect analysis of biomineralization for solidifying desert sands. Biogeotechnics. 2, 100065 (2024).

Zhang, X., Zhou, B., You, L. H., Wu, Z. Y. & Wang, H. B. Cementation anisotropy associated with microbially induced calcium-carbonate precipitation and its treatment effect on calcareous and quartz sands. Constr. Build. Mater.395, 132237 (2023).

Deng, X. J. et al. Cementing mechanism of MICP-treated mortar and performance improvement by innovative molds. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.36, 04024150 (2024).

Tang, C. S. et al. Factors affecting the performance of microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) treated soil: a review. Environ. Earth Sci.79, 94 (2020).

Yu, T. et al. Review on engineering properties of MICP-treated soils. Geomech. Eng.27, 13–30 (2021).

Wang, Z. Y. et al. Review of ground improvement using microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). Mar. Georesour Geotechnol. 35, 1135–1146 (2017).

Baek, S., Kwon, T. & DeJong, J. T. Reductions in hydraulic conductivity of sands caused by microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng.150, 11570 (2024).

Li, M. D. et al. Effects of sorbitol and sucrose on soybean-urease induced calcium carbonate precipitate. Biogeotechnics. 1, 100052 (2023).

Yang, Y. J. et al. The effect of nucleating agents on enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation and corresponding microscopic mechanisms. Materials. 15, 5814 (2022).

Li, D. M. et al. Enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation using yellow soybean for eco-friendly treatment of expansive. Soils Int. J. Geomech.24, 04024007 (2024).

Miftah, A., Tirkolaei, H. K. & Bilsel, H. Bio-precipitation of CaCO3 for soil improvement: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng.800, 012037 (2020).

Pakbaz, M. S., Kolahi, A. & Ghezelbash, G. R. Assessment of microbial induced calcite precipitation (MICP) in fine sand using native microbes under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Ksce J. Civ. Eng.26, 1051–1065 (2022).

Liang, S. H. et al. Influence of fiber type and length on mechanical properties of MICP-treated sand. Mater. 15, 4017 (2022).

Wang, X. R., Li, C. & He, J. A highly effective strain screened from soil and applied in cementing fine sand based on MICP-bonding technology. J. Biotechnol.350, 55–66 (2022).

Imran, M. A. et al. Durability improvement of biocemented sand by fiber-reinforced MICP for coastal erosion protection. Mater. 15, 2389 (2022).

Zhao, J. T. et al. Effects of different types of fibers on the physical and mechanical properties of MICP-treated calcareous sand. Mater. 14, 268 (2021).

Saracho, A. C., Haigh, S. K. & Jorat, M. E. Flume study on the effects of microbial induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) on the erosional behaviour of fine sand. Geotechnique. 71, 1135–1149 (2021).

Wu, S. F., Li, B. & Chu, J. Stress-dilatancy behavior of MICP-treated sand. Int. J. Geomech.21, 04020264 (2021).

Lai, Y. M. et al. Experimental study to improve the mechanical properties of iron tailings sand by using MICP at low pH. Constr. Build. Mater.273, 121729 (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. Micro-experiment on MICP-treated aeolian sandy soil under ultraviolet erosion environment. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng.42, 254–258 (2020).

Ming, D. G. et al. Experimental study on effect of calcium source on bio-cementation of aeolian sand. Yellow River. 42, 85–88 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Field experimental study on stability of bio-mineralization crust in the desert. Rock. Soil. Mech.40, 1291–1298 (2019).

Tian, K. L. et al. Increasing wind erosion resistance of aeolian sandy soil by microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Land. Degrad. Dev.29, 4271–4281 (2018).

Tian, K. L. et al. Effect of reactant injection rate on solidifying aeolian sand via microbially induced calcite precipitation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.32, 04020291 (2020).

Dubey, A. A. et al. Experimental investigation to mitigate aeolian erosion via biocementation employed with a novel ureolytic soil isolate. Aeolian Res.52, 100727 (2021).

Devrani, R. et al. Applications of bio-cementation and bio-polymerization for aeolian erosion control. J. Arid Environ.187, 104433 (2021).

GB/T. 50123 – 2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method (Construction Ministry of PRC: Beijing, China, 2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Experimental study on permeability and strength characteristics of MICP-treated calcareous sand. Biogeotechnics. 1, 100034 (2023).

Yang, D., Xu, G. & Duan, Y. Effect of particle size on mechanical property of bio-treated sand foundation. Appl. Sci.10, 8294 (2020).

Wu, J. Z. et al. Chongqing University Press,. University Chemistry. 107–135 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Mechanical properties of eolian sand solidified by microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP). Geomicrobiol. J.40, 688–698 (2023).

Tasuji, M. A. et al. Experimental investigation of sandy soil stabilization using chitosan biopolymer. Transp. Geotech.46, 101266 (2024).

He, J. et al. Research advances in biogeotechnologies. Chin. J. Geo Eng.38, 643–653 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Advances in soil cementation by biologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Rock. Soil. Mech.43, 345–357 (2022).

Fouladi et al. Application of microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) technology in construction materials: a comprehensive review of waste stream contributions. Constr. Build. Mater.388, 131546 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. A review on the application of microbial induced carbonate precipitation to concrete surface protection. J. Build. Mater. 1–17 (2024).

Tian, Z. F. et al. Experimental study and mechanism analysis on sand reinforcement with different compositions of biological solution. J. Harbin Inst. Technol.52, 120–126 (2020).

Wen, K. J. et al. Impact of bacteria and urease concentration on precipitation kinetics and crystal morphology of calcium carbonate. Acta Geotech.15, 17–27 (2020).

Zhao, D. D. et al. Stabilizing mechanisms of metastable vaterite in cement systems. Cem. Concr Res.178, 107441 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (2021JM-535), Scientific Research Program Funded by Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial Government (23JS061) and Provincial Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (S202312715038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L. and J.L. contributed to the paper conception; J.L. provided the method; X.Q.H. and X.L. validated the writing; Y.J.Z. contributed significantly to the writing of the original draft; G.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript; G.L. acquired funding. All authors read and agreed for the publishment of the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Zhang, Yj., Hua, Xq. et al. Mechanical properties of aeolian sand cemented via microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP). Sci Rep 14, 22745 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73986-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73986-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Freeze–Thaw Effects on the Mechanical Behavior of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Cemented Aeolian Sand

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2026)

-

Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation: A Critical Review on a Sustainable Method for Improving Expansive Soil in the Era of Climate Change

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Microbial induced calcite precipitation for improving low-cohesive soil: mechanisms, methods and macroscopic properties

Low-carbon Materials and Green Construction (2024)