Abstract

While foraging, marine predators integrate information about the environment often across wide-ranging oceanic foraging grounds and reflect these in population parameters. One such species, the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis; SRW) has shown alterations to foraging behaviour, declines in body condition, and reduced reproductive rates after 2009 in the South African population. As capital breeders, these changes suggest decreased availability of their main prey at high-latitudes, Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). This study analysed environmental factors affecting prey availability for this population over the past 40 years, finding a notable southward contraction in sea ice, a 15–30% decline in sea ice concentration, and a more than two-fold increase in primary production metrics after 2008. These environmental conditions are less supportive of Antarctic krill recruitment in known SRW foraging grounds. Additionally, marginal ice zone, sea ice concentration and two primary production metrics were determined to be either regionally significant or marginally significant predictors of calving interval length when analysed using a linear model. Findings highlight the vulnerability of recovering baleen whale populations to climate change and show how capital breeders serve as sentinels of ecosystem changes in regions that are difficult or costly to study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change has strong effects on marine ecosystems and its impacts have ramifications throughout the food web1,2,3. In the Southern Ocean (SO), responses to climate change vary regionally and are often masked due to high levels of natural variability3,4,5. The use of sentinel species in improving our understanding of environmental change is quickly gaining recognition, particularly in data-sparse and highly variable regions such as the SO6,7. Baleen whales are especially useful in this regard due to their life histories as migratory capital breeders, which entails a period of intensive feeding that must fulfill the immense energetic requirements associated with reproduction8,9,10.

One such baleen whale, the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis; hereafter SRW), has been monitored extensively since 1979 in the South African calving ground to assess its continued recovery from extensive whaling11,12,13. Although the population is still growing steadily, results of this long time series reveal a decline in reproductive rates after 2009, with an increased probability of a female needing two consecutive resting years between calving14. Over the same period a decline in maternal body condition15, and a northward shift in foraging distribution were also observed16,17. Due to the temporal scale, these databases provide an opportunity to explore potential environmental drivers behind the observed changes.

Based on historical whaling and telemetry data, South African SRWs are known to make use of high-latitude foraging grounds18,19, with Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) playing a significant role in meeting the energy requirements essential for reproduction20,21. This dependence on krill stems from analyses of the stomach contents of 249 SRW caught during the illegal soviet whaling activities, with 99% of the stomachs of whales caught south of 50°S containing Euphausiids (although it is not specified whether all were Antarctic krill)18. Additionally, there are anecdotal reports of SRW feeding on Antarctic krill22,23.

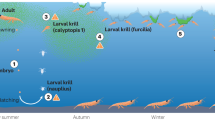

The observed reduction in reproductive rates and maternal body condition in South African SRW are therefore believed to be strongly linked to reduced availability of Antarctic krill15,20,21,24. In turn, Antarctic krill have an intimate relationship with sea ice, using it primarily as a foraging habitat that offers protection from predation, particularly during early developmental stages25,26. This association with sea ice and the role of environmental parameters in modulating the primary production necessary to support high densities of Antarctic krill results in vulnerability to environmental change27,28. In fact, it has been proposed that large-scale recruitment failure of Antarctic krill due to unfavourable environmental conditions in a given year can lead to a 3-to 4 fold variation in Antarctic krill biomass and take several years of good conditions to regain initial densities29.

A wealth of krill data has been collected over the last century, particularly along the Antarctic Peninsula and south-west Atlantic34. However, due to a shortage of repeat surveys, the patchy nature of Antarctic krill swarms and inconsistencies in sampling methods in the region of interest, assessing changes in prey distribution and biomass over the period of observed population level changes is not possible28. Therefore, proxies for foraging habitat quality are necessary in evaluating changes in environmental conditions which are known to alter prey availability (Fig. 1).

Here, we use an approach guided by our knowledge of South African SRW population demographics, as well as migratory and foraging behaviour to assess environmental changes that may have rendered high-latitude foraging grounds less favourable for Antarctic krill recruitment. We investigate temporal patterns in four variables which characterize Antarctic krill availability across the known foraging domain of South African SRW’s. In doing this, we evaluate the threat that future climate change imposes on krill-predators including still-recovering baleen whales, as well as the utility of baleen whale populations in monitoring the impacts of climate change on ecosystem functioning in the SO.

Methods

All statistical analysis and plots were performed using the R language environment30, with the exception of the spatial plots in Fig. 6 which were created with QGIS version 3.26.1.

Calving interval

Annual aerial surveys of the South African SRW calving ground have been conducted since 1979 between Nature’s Valley and Muizenberg, providing an extensive time-series of population demographic data. During these surveys, photographs of individuals, with a focus on mothers with calves, are taken to allow for individual identification through distinct callosity patterns and variations in dorsal pigmentation31. This process allows for matches between years to be made, and from this, to calculate the calving interval as described in Best et al. (2001). Three-year calving intervals are considered normal for SRW, including one year of gestation, one year of lactation and one year of recovery13,32. Four-year intervals are regarded as either coming from a failure to conceive (and thus an extra year of recovery) or an early abortion, whereas 5-year intervals are regarded as stemming from late-term abortions32. Both 4- and 5-year intervals are thus regarded as reproductive failure. In this study, only details of 3-, 4- and 5-year intervals are provided, because longer calving intervals are difficult to interpret as they may include missed observations.

Study area: feeding grounds and Antarctic krill data

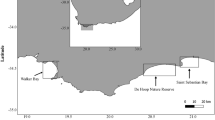

The core feeding regions for South African SRWs were inferred from American (1780–1920) and Soviet whaling (1951–1971) data as well as from a telemetry study conducted in 200118,19,33. Due to the potential spatial bias of whaling data, the study area was not limited to those areas with catches alone. Instead, a grid (divided by 5° latitude ×25° longitude cells) was used to connect areas of whaling catches and regions frequented by individuals tagged by Mate et al. (2011), creating a total of 16 regions (Fig. 2).

Selected regions (Regions 1–16) representing South African southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) foraging grounds. Orange boxes combine regions where sea ice was analysed and referred to as 14+ (combination of Regions 11 and 14), 15+ (combination of Regions 12 and 15), and 16+ (combination of Regions 13 and 16) in the text. Colours represent the mean summer (January, February, and March) chlorophyll concentrations (2000–2020) from https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov using Terra-MODIS data, and the dashed line represents the mean position of the September 60% sea ice concentration contour (1988–2020) from Climate Data Records (CDR) from NOAA/NSIDC.

Antarctic krill density and distribution data were obtained from KRILLBASE34. Densities from individual net hauls collected during surveys between 1926 and 2016 were averaged over a 2° × 2° grid.

Measures of foraging habitat quality

Four measures of potential foraging habitat quality were analysed over the period. Satellite-derived chlorophyll was used to develop two indicators of general foraging conditions for SRW’s, and two variables of sea ice were used as measures of Antarctic krill habitat suitability.

Chlorophyll

Daily 4 km resolution Terra-MODIS chlorophyll (mg/m3) ocean colour data were obtained from https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov as a proxy for potential food availability through primary production. From these data, a monthly chlorophyll index was calculated for each of the 16 regions by computing the pixel-wise monthly cumulative sum from daily chlorophyll data and calculating the spatial average for each region in every month (2000–2020). Only months with more than 90% of measurement days were included. The monthly standard deviation of mean monthly chlorophyll was calculated and averaged for each region as a measure of food variability over the same period (2000–2020). The anomalies were calculated by subtracting the monthly means from the mean climatology of the seasonal cycle over the whole period (2000–2020). Three-year moving means were calculated for the Monthly Chlorophyll Index and chlorophyll standard deviation using the Zoo package in R35.

Sea ice

All sea ice data was derived from 25 km resolution sea ice concentration data from the sea ice Climate Data Records (CDR) from NOAA/NSIDC to make sea ice metrics comparable36,37. Regions influenced by sea ice (Regions 11–16) were pooled into longitudinal bands and were named based on the three most southerly regions (Region 14+ combines Regions 11 and 14; Region 15+ combines Region 12 and 15; Region 16+ combines Region 13 and 16; see Fig. 2). The mean monthly sea ice concentration (SIC) was calculated for each region. The marginal ice zone (MIZ) variability indicator proposed by Vichi (2022) was used38, which is defined as the standard deviation of daily SIC anomalies from the monthly mean. The mean monthly MIZ extent (for the period 1988–2020) was calculated by filtering out pixels with low chances of encountering MIZ conditions38, and calculating the area by summing the number of pixels and multiplying by the pixel area. Monthly MIZ extent and SIC anomalies were calculated by subtracting the climatological monthly cycle computed over the 1988–2020 period. Five-year moving means were calculated for SIC and MIZ extents using the Zoo package in R35. Additionally, spatial anomaly plots of the MIZ variability indicator and SIC for October and November are also presented to highlight changes over selected periods before and after 2009, being the onset of the observed changes in SRW reproductive rates. These diagnostics were created by computing 5-year means and subtracting them from the 1988–2020 mean.

Linear models

Linear models were developed to quantitatively assess the temporal relationship between MIZ, SIC, Monthly Chlorophyll Index, chlorophyll standard deviation and calving interval. To test this, a linear model was fitted to the annual rolling mean of each predictor, with the calving interval as the response variable. Only the years 2000–2020 were assessed since this is the time range with data from all four variables. The predictor variables were MIZ extent, SIC, Chlorophyll Index, and chlorophyll standard deviation at 1- and 2-year lags. This is under the hypothesis that, at the individual level, and assuming a 3-year calving interval, foraging conditions within the 2 years leading up to a mother giving birth are the most influential determinant of reproductive success9. All predictor variables were normally distributed. However, the calving interval was lognormally distributed, so the natural logarithm of the calving interval was used in the model. Collinearity between continuous predictors was assessed using a cross-correlation matrix. A high threshold of collinearity (r > 0.9) was chosen since the focus of this exercise was to assess the role of all variables investigated and collinearity between highly related variables is inevitable. Predictors were considered significant at the p < 0.05 level, and marginally significant between 0.05 < p < 0.10. Three linear models were developed for each of the three sea ice regions (Regions 14+ , 15+ , and 16+).

Results

Calving interval

The period between 1983 and 2009 was characterized by a high proportion of 3-year calving intervals, with a mean proportion ± standard deviation of 0.86 ± 0.05 (Fig. 3). Between 2010 and 2015, the proportion of 3-year calving intervals declined rapidly, and 4- and 5-year calving intervals became more prevalent. The mean proportion ± standard deviation of 3-year calving intervals between 2010 and 2020 was 0.46 ± 0.15. Following this period, 2016–2020 saw a cessation to this rapid decline in 3-year calving intervals, with variable proportions in 3-, 4- and 5-year intervals (Fig. 3).

Regional changes in monthly chlorophyll index

Monthly chlorophyll index displayed considerable regional and temporal variability. Generally, regions north of 45°S revealed no noteworthy changes over the period (Fig. 4a, b). An exception to this was Region 6 which experienced an increase in chlorophyll production biomass after 2015 (Supplementary Fig. S1d). More southerly regions, particularly south of 50°S exhibited substantial increases in monthly chlorophyll index after 2009 in December–March (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Fig. S2d, S3). This signal was strongest in Regions 11 and 12 (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. 3d respectively).

Heat maps of monthly chlorophyll index for selected regions (2000–2020). Monthly mean chlorophyll index heat maps for (a) Region 2, (b) Region 4, (c) Region 8 and (d) Region 12 over the time series (2000–2020). Grey blocks indicate months which had insufficient observations to compute the monthly chlorophyll index (see Sect “Methods”). Refer to Supplementary for regions not depicted here.

Environmental changes to the seasonal sea ice zone

The three sea ice regions displayed high-levels of month-to-month variability. Two distinct periods of reduced sea ice were observed over the time series. The first period occurred between 1996 and 2002 and was centred over Region 16+ , with declines in both SIC and MIZ extent in this region, but only in SIC in Regions 14+ and 15+ (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5). The second period occurred between 2008 and 2014 and was most intense in Regions 14+ and 15+ with substantial declines in both MIZ extent and SIC (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). Patterns in primary production metrics mirrored these observed changes in sea ice, with elevated Monthly Chlorophyll Index and chlorophyll standard deviation during periods of reduced SIC and MIZ extent, and increased MIZ variability (Fig. 5 c,d and Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). A notable and abrupt increase in both Monthly Chlorophyll Index and chlorophyll standard deviation was observed after 2009 in Regions 14+ and 15+ (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. S4). Region 16+ also experienced an increase in primary production metrics after 2009, however, highest positive anomalies occurred between 2011 and 2016.

Indicators for Region 15+ . Monthly anomalies (top panel) and rolling mean of the anomaly (bottom panel) for (a) mean monthly marginal ice zone (MIZ) extent anomaly compared to the 1988–2020 mean, (b) mean monthly sea ice concentration anomaly (SIC) compared to the 1988–2020 mean, (c) monthly chlorophyll index anomaly compared to the 2000–2020 mean and (d) Monthly chlorophyll standard deviation anomaly compared to the 2000–2020. The grey-shaded region highlights the period of reduced southern right whale reproductive success after 2009 (refer to Fig. 3). Refer to Supplementary for regions not depicted here.

Spatial data shown in Fig. 6 provides some context to the regional and temporal variability in sea ice signals shown in Fig. 5. Sea ice anomalies of 5-year periods help to elucidate large-scale changes to the sea ice environment, focussing on the two distinct periods of negative SIC anomalies observed over the time-series (Fig. 6). The period between 2008 and 2012 reveals an expansive area of negative SIC anomalies, and southward contraction in the MIZ along the Antarctic Peninsula and South Atlantic, encompassing the region where most of the global Antarctic krill stock resides (Fig. 6). This configuration of anomalies was unique to the timeframe examined (see Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). On the contrary, the period of reduced sea ice between 1998 and 2002 revealed no clear pattern in the spatial distribution of anomalies, particularly over important regions for Antarctic krill (Fig. 6).

Sea ice concentration (SIC) and marginal ice zone (MIZ) indicator anomalies. The two periods of reduced sea ice (1998–2002 and 2008–2012) are presented here to compare the spatial configuration in anomalies. The anomalies represent 5-year means compared to the 1988–2020 mean. Antarctic krill densities from surveys between 1926 and 2016 are also presented33. Refer to Supplementary figures for regions not depicted here.

Effect of environmental variables on calving interval

All variables analysed were found to influence calving intervals but in different regions and with variable significance (see Table 1). In Region 14+ , Monthly Chlorophyll index and chlorophyll standard deviation at 1-year lags were the only variables significantly impacting calving intervals (p = 0.035 and 0.029 respectively). In Region 15+ , MIZ extent at a 2-year lag (p = 0.003) and SIC at a 2-year lag (p = 0.023 and 0.04 respectively) were found to impact calving intervals significantly. Additionally, MIZ extent (p = 0.056), chlorophyll index (p = 0.058) and chlorophyll standard deviation (p = 0.09) were found to be marginally significant predictors. No environmental predictors in Region 16+ were found to significantly influence calving intervals.

Discussion

This study reveals large-scale enivoronmental changes in the seasonal sea ice zone in important foraging grounds for South African SRWs, which likely drove a decline in the population’s reproductive success14,15,16. A southward contraction in sea ice marked by a decrease in MIZ extent and a decline in SIC of up to 15–30% over 5 years affected the region where most of the Antarctic krill stock is known to reside between 2008 and 2012. These reductions occurred in conjunction with a more than two-fold increase in primary producers’ biomass in regions that experienced the greatest declines in sea ice. Furthermore, all variables assessed were either found to be significant or marginally significant predictors of calving interval length when fitted with a linear model. Due to the intimate relationship between sea ice and Antarctic krill, these changes are likely to be an indication of reduced prey availability for SRWs at high-latitudes. On the other hand, mid-latitude foraging grounds (regions north of 50°S) experienced regional increases in chlorophyll metrics but no indication of changes that would have ramifications for prey abundance at large spatial scales.

The influence of food availability on calving success is well documented in baleen whales due to the elevated energetic costs associated with reproduction39,40,41. Specifically in SRW, sea ice has been shown to influence population demographics due to its crucial role in the recruitment success of Antarctic krill20,21,24,25,26,28,42. Considerable uncertainty exists about the true nature of the relationship between sea ice and Antarctic krill abundance and biomass. Despite these uncertainties, the role of sea ice in providing sheltered foraging habitat is well established28. Antarctic krill have relatively long and complex life histories and may be dependent on repeated years of favourable ice conditions43,44. Additionally, the presence of sea ice is a strong mediator of ecosystem state and plays a pivotal role in shaping community assemblages. Low ice years, for example, have been found to result in the dominance of gelatinous zooplankton such as salps (Salpa thompsoni)43,45. Sea ice has been impacted by climate change through ocean and atmospheric warming46 and increased poleward wind stress associated with a more positive Southern Annular Mode which prevents sea ice expansion47,48. Therefore, there is considerable concern within the scientific community on the fate of Antarctic krill in the face of rapid climate change28.

The global Antarctic krill population is predominantly concentrated along the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Atlantic Ocean, with the former considered a vital source region for the latter25,45,49,50. Based on sea ice conditions described here, the years between 1988 and 2003 appeared to be highly favourable for Antarctic krill recruitment, with extensive sea ice cover over the Antarctic Peninsula and South Atlantic region of the SO. Changes began occurring in the 2000s along the Antarctic Peninsula, with declines in SIC and reduced stability of the MIZ. The analysis performed by Ichii et al. (2023) also revealed a regime shift after the 2000s, characterised by significantly reduced probabilities of Antarctic krill transport from the Antarctic Peninsula to the South Atlantic region due to reduced sea ice cover52. Therefore, changes to transport processes because of declines in sea ice likely began to negatively impact prey abundance in regions reliant on source regions such as South Georgia and Bouvet Island after 200050,51,52.

Linear models only indicated a significant effect of sea ice, particularly MIZ extent, in region 15+ . Region 14+ displayed high levels of month-to-month variability in MIZ extent and SIC, which likely prevented a significant effect of sea ice on calving intervals from emerging. Region 16+ also didn’t reveal any sea ice effects, however this is likely due to the atmospheric circulation patterns that drive regional changes in sea ice extent. The sea ice contraction that occurred in the late 2000s and early 2010s was driven by the presence of the Amundsen Sea Low, which acts to reduce ice along the Antarctic Peninsula, and expand ice over the South Indian Ocean53.

In conjunction with changes in the sea ice environment post-2009, primary production substantially increased in almost all high-latitude feeding grounds. Additionally, primary production metrics were significant, and marginally significant predictors of calving interval in Regions 14+ and 15+ respectively. Towards the end of the timeseries (2016–2020), primary production and sea ice metrics return to conditions similar to those seen prior to the increase in calving cycles. At the same time, some recovery is evident in the calving interval, however 4- and 5-year intervals were still more prevalent than 3-year intervals.

The increasing trends in chlorophyll concentration are in line with other analyses of chlorophyll trends in the seasonal sea ice zone and are likely a reflection of changes in sea ice dynamics which drive changes in primary production and phytoplankton community structure54,55,56,57. Reduced sea ice extends the growth season for pelagic phytoplankton due to increased periods of open-water conditions from an earlier retreat and later onset of sea ice growth, which allows for more solar radiation to penetrate the water column57. At the same time, ice-dependent zooplankton experience a shorter duration of protection under the sea ice habitat, potentially affecting their life histories and rendering them more susceptible to predation58,59. Furthermore, salps have been found to outcompete Antarctic krill under low ice regimes due to faster reproductive and clearance rates, with studies along the Antarctic Peninsula reporting increases in the ratio of salps to krill in recent years43,60,61. Reduced grazing rates on phytoplankton during periods of low Antarctic krill stocks may have also contributed to the elevated primary production observed in the open ocean62. For example, Ryabov et al., (2017) reported the occurrence of stronger seasonal blooms and increased phytoplankton biomass during periods of reduced Antarctic krill biomass27. Additional pressure on Antarctic krill stocks is likely being added by recovering baleen whale populations, particularly humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) and fin (Balaenoptera physalus) whales, as well as the growing Antarctic krill fishery63,64,65,66. Indeed, intraspecific competition for Antarctic krill is likely increasing as most species recover from commercial whaling67,68. This will inevitably result in the emergence of density-dependent changes in foraging behaviour with implications for reproductive success. Unlike what is observed here, such changes would likely be gradual as species steadily recover, and would act as an additional pressure determining the carrying capacity of the system under different regimes of climate variability. How other krill-dependent species are impacted by the observed environmental changes is difficult to ascertain as time series data on demographic parameters of marine predators, particularly SO baleen whales, are scarce.

Additional data indicative of a South African SRWs response to changing climate conditions in their high latitude foraging grounds relates to changes in their foraging behaviour. This was inferred from shifts in stable isotope values over the same period as the observed declines in reproductive rates16, with a suggested reduction in the use of historically important high-latitude foraging grounds17. However, it is evident that these adaptive strategies through altering migratory behaviour are associated with energetic costs as revealed by Vermeulen et al. (2023). These energetic costs may arise due to reduced foraging efficiency in the high-latitudes, individuals having to undertake longer migrations, and/or ecological traps arising from site fidelity to foraging grounds16,69,70. Ecological traps arise due to the continued usage of learned migratory routes despite environmental changes which have rendered regions unfavourable for foraging. Therefore, females may be taking longer to achieve the energy requirements necessary to produce a calf, thereby decreasing in body condition15, and lengthening their calving interval14.

The presented results highlight the sensitivity of SRWs to environmental variability in their foraging grounds and the risk that climate change poses to continued population recovery post-whaling. This sensitivity also reveals the potential of the species as climate change sentinels in a system of ever-increasing rates of change and the potential baleen whales hold in improving our knowledge of future impacts of climate change in the SO and other krill-dependent predators.

Data availability

All chlorophyll and sea ice concentration metrics were obtained from online sources (refer to Sect “Methods”). The marginal ice zone indicator and calving interval data sets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hastings, R. A. et al. Climate change drives poleward increases and equatorward declines in marine species. Curr. Biol. 30, 1572–1577 (2020).

Hodapp, D. et al. Climate change disrupts core habitats of marine species. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3304–3317 (2023).

Trathan, P. N., Forcada, J. & Murphy, E. J. Environmental forcing and Southern Ocean marine predator populations: Effects of climate change and variability. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 362, 2351–2365 (2007).

Zhang, L., Delworth, T. L., Cooke, W. & Yang, X. Natural variability of Southern Ocean convection as a driver of observed climate trends. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 59–65 (2019).

Shokr, M. & Ye, Y. Why does Arctic Sea ice respond more evidently than Antarctic Sea ice to climate change?. Ocean Land Atmos. Res. 2, 0006 (2023).

Hindell, M. A. et al. Tracking of marine predators to protect Southern Ocean ecosystems. Nature 580, 87–92 (2020).

Hazen, E. L. et al. Marine top predators as climate and ecosystem sentinels. Front. Ecol. Environ. 17, 565–574 (2019).

Christiansen, F. et al. Fetal growth, birth size and energetic cost of gestation in southern right whales Key points. J. Physiol. 600, 1–22 (2022).

Christiansen, F., Sprogis, K. R., Nielsen, M. L. K., Glarou, M. & Bejder, L. Energy expenditure of southern right whales varies with body size, reproductive state and activity level. J. Exp. Biol. 226, 245137 (2023).

Williamson, M. J., Doeschate, M. T. I., Deaville, R., Brownlow, A. C. & Taylor, N. L. Cetaceans as sentinels for informing climate change policy in UK waters. Mar. Policy 131, 104634 (2021).

Best, P. B. The Status of Right Whales off South Africa (1969–1979) (Sea Fisheries Institute, 1981).

Best, P. B. Trends in the inshore right whale population off South Africa, 1969–1987. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 6, 93–108 (1990).

Best, P. B., Brandão, A. & Butterworth, D. S. Demographic parameters of southern right whales off South Africa. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2, 161–169 (2001).

Brandão, A., Ross-Gillespie, A., Vermeulen, E. & Butterworth, D. A photo-identification-based assessment model of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) surveyed in South African waters, with a focus on recent low counts of mothers with calves. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 45, 15–27 (2023).

Vermeulen, E., Thavar, T., Glarou, M., Ganswindt, A. & Christiansen, F. Decadal decline in maternal body condition of a Southern Ocean capital breeder. Sci. Rep. 13, 3228 (2023).

van den Berg, G. L. et al. Decadal shift in foraging strategy of a migratory southern ocean predator. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 1052–1067 (2021).

Derville, S. et al. Long-term stability in the circumpolar foraging range of a Southern Ocean predator between the eras of whaling and rapid climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2214035120 (2023).

Tormosov, D. D. et al. Soviet catches of southern right whales Eubalaena australis, 1951–1971. Biological data and conservation implications. Biol. Conserv. 86, 185–197 (1998).

Mate, B. R., Best, P. B., Lagerquist, B. A. & Winsor, M. H. Coastal, offshore and migratory movements of South African right whales revealed by satellite telemetry. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 27, 455–476 (2011).

Seyboth, E. et al. Southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) reproductive success is influenced by krill (Euphausia superba) density and climate. Sci. Rep. 6, 28205 (2016).

Leaper, R. et al. Global climate drives southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) population dynamics. Biol. Lett. 2, 289–292 (2006).

Hamner, W. M., Stone, G. S. & Obst, B. S. Behavior of southern right whales, Eubalaena australis, feeding on the Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba. Fish. Bull. 86, 143–150 (1988).

Calderan, S. V. et al. Observations of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) surface feeding on krill in austral winter at South Georgia. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 39, 1–7 (2023).

Agrelo, M. et al. Ocean warming threatens southern right whale population recovery. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2823 (2021).

Veytia, D. et al. Overwinter sea-ice characteristics important for Antarctic krill recruitment in the southwest Atlantic. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107934 (2021).

Meyer, B. et al. The winter pack-ice zone provides a sheltered but food-poor habitat for larval Antarctic krill. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1853–1861 (2017).

Ryabov, A., Berger, U., Blasius, B. & Meyer, B. Driving forces of Antarctic krill abundance. Sci. Adv. 9, 1–15 (2023).

Kawaguchi, S. et al. Climate change impacts on Antarctic krill behaviour and population dynamics. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 43–58 (2024).

Priddle, J. et al. Large-scale fluctuations in distribution and abundance of Krill—A discussion of possible causes. Antarct. Ocean Resour. Var. 1, 169–182 (1988).

R Core Team 2023 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Best, P. B. Natural markings and their use in determining calving intervals in right whales off South Africa. S. Afr. J. Zool. 25, 114–123 (1990).

Knowlton, A. R., Kraus, S. D. & Kenney, R. D. Reproduction in North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis). Can. J. Zool. 72, 1297–1305 (1994).

Smith, T. D., Reeves, R. R., Josephson, E. A. & Lund, J. N. Spatial and seasonal distribution of American whaling and whales in the age of sail. PLoS One 7, e34905 (2012).

Atkinson, A. et al. KRILLBASE: A circumpolar database of Antarctic krill and salp numerical densities, 1926–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 193–210 (2017).

Zeileis, A., Grothendieck, G., Ryan, J. A. & Andrews, F. Package ‘ zoo’. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/zoo/index.html (2014).

Peng, G., Meier, W. N., Scott, D. J. & Savoie, M. H. A long-term and reproducible passive microwave sea ice concentration data record for climate studies and monitoring. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 5, 311–318 (2013).

Meier, W. N., et al. NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration, Version 3. [02/1988 - 12/2020]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center. https://doi.org/10.7265/N59P2ZTG (2017).

Vichi, M. An indicator of sea ice variability for the Antarctic marginal ice zone. Cryosphere 16, 4087–4106 (2022).

Greene, C. H., Pershing, A. J., Kenney, R. D. & Jossi, J. W. Impact of climate variability on the recovery of endangered North Atlantic right whales. Oceanography 16, 98–103 (2003).

Miller, C. A. et al. Blubber thickness in right whales Eubalaena glacialis and Eubalaena australis related with reproduction, life history status and prey abundance. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 438, 267–283 (2011).

Williams, R. et al. Evidence for density-dependent changes in body condition and pregnancy rate of North Atlantic fin whales over four decades. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 70, 1273–1280 (2013).

Flores, H. et al. The association of Antarctic krill Euphausia superba with the under-ice habitat. PLoS One 7, e31775 (2012).

Loeb, V. et al. Effects of sea-ice extent and krill or salp dominance on the Antarctic food web. Nature 387, 897–900 (1997).

Quetin, B. L. & Ross, M. R. Life under Antarctic Pack Ice: A Krill Perspective (Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2009).

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. & Rothery, P. Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature 432, 100–103 (2004).

Cai, W. et al. Southern Ocean warming and its climatic impacts. Sci. Bull. 68, 946–960 (2023).

Swart, N. C., Fyfe, J. C., Saenko, O. A. & Eby, M. Wind-driven changes in the ocean carbon sink. Biogeosciences 11, 6107–6117 (2014).

Sallée, J. B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Hofmann, E. E. & Murphy, E. J. Advection, krill, and Antarctic marine ecosystems. Antarct. Sci. 16, 487–499 (2004).

Green, D. B. et al. Modeling Antarctic krill circumpolar spawning habitat quality to identify regions with potential to support high larval production. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL091206 (2021).

Fevolden, S. E. Krill off Bouvetöya and in the southern Weddell Sea with a description of larval stages of Euphausia crystallorophias. Sarsia 65, 149–162 (1980).

Ichii, T. et al. Impact of the climate regime shift around 2000 on recruitment of Antarctic krill at the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia. Prog. Oceanogr. 213, 103020 (2023).

Turner, J., Scott Hosking, J., Marshall, G. J., Phillips, T. & Bracegirdle, T. J. Antarctic sea ice increase consistent with intrinsic variability of the Amundsen sea low. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2391–2402 (2016).

Behera, N., Swain, D. & Sil, S. Effect of Antarctic sea ice on chlorophyll concentration in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res. II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 178, 104853 (2020).

Del Castillo, C. E., Signorini, S. R., Karaköylü, E. M. & Rivero-Calle, S. Is the Southern Ocean getting greener Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6034–6040 (2019).

Ryan-Keogh, T. J., Thomalla, S. J., Monteiro, P. M. S. & Tagliabue, A. Multidecadal trend of increasing iron stress in Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Science 379, 834–840 (2023).

Thomalla, S. J., Nicholson, S. A., Ryan-Keogh, T. J. & Smith, M. E. Widespread changes in Southern Ocean phytoplankton blooms linked to climate drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 975–984 (2023).

David, C. L. et al. Sea-ice habitat minimizes grazing impact and predation risk for larval Antarctic krill. Polar Biol. 44, 1175–1193 (2021).

Flores, H. et al. Sea-ice decline could keep zooplankton deeper for longer. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1122–1130 (2023).

Plum, C., Hillebrand, H. & Moorthi, S. Krill vs salps: dominance shift from krill to salps is associated with higher dissolved N: P ratios. Sci. Rep. 10, 5911 (2020).

Pietzsch, B. W. et al. The impact of salps (Salpa thompsoni) on the Antarctic krill population (Euphausia superba): an individual-based modelling study. Ecol. Process 12, 50 (2023).

Ryabov, A. B., de Roos, A. M., Meyer, B., Kawaguchi, S. & Blasius, B. Competition-induced starvation drives large-scale population cycles in Antarctic krill. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0177 (2017).

Trathan, P. N. What is needed to implement a sustainable expansion of the Antarctic krill fishery in the Southern Ocean?. Mar. Policy 155, 105770 (2023).

Seyboth, E., Meynecke, J. O., de Bie, J., Roychoudhury, A. & Findlay, K. A review of post-whaling abundance, trends, changes in distribution and migration patterns, and supplementary feeding of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.997491 (2023).

Herr, H. et al. Return of large fin whale feeding aggregations to historical whaling grounds in the Southern Ocean. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13798-7 (2022).

Ryan, C. et al. Commercial krill fishing within a foraging supergroup of fin whales in the Southern Ocean. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.4002 (2023).

Branch, T. A. Humpback whale abundance south of 60°S from three complete circumpolar sets of surveys. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2, 53–69 (2011).

Branch, T. A., Matsuoka, K. & Miyashita, T. Evidence for increases in Antarctic blue whales based on Bayesian modelling. Mar. Mam. Sci. 20, 726–754 (2023).

Vermeulen, E. et al. Swimming across the pond: First documented transatlantic crossing of a southern right whale. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 40, 309–316 (2023).

Valenzuela, L. O., Sironi, M., Rowntree, V. & Seger, J. Isotopic and genetic evidence for culturally inherited site fidelity to feeding grounds in southern right whales. Mol. Ecol. 18, 782–791 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. wrote the paper, performed the analysis and assisted with conceptualizing the idea. M.V. provided guidance, assisted with conceptualizing the idea and edited the manuscript. E.V. provided guidance, assisted with conceptualizing the idea and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Germishuizen, M., Vichi, M. & Vermeulen, E. Population changes in a Southern Ocean krill predator point towards regional Antarctic sea ice declines. Sci Rep 14, 25820 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74007-1

This article is cited by

-

Four decades of annual monitoring reveal declining reproductive success of a migratory baleen whale

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Southern Ocean humpback whales are shifting to an earlier return migration

Scientific Reports (2025)