Abstract

Self-supervised learning methods for medical images primarily rely on the imaging modality during pretraining. Although such approaches deliver promising results, they do not take advantage of the associated patient or scan information collected within Electronic Health Records (EHR). This study aims to develop a multimodal pretraining approach for chest radiographs that considers EHR data incorporation as an additional modality that during training. We propose to incorporate EHR data during self-supervised pretraining with a Masked Siamese Network (MSN) to enhance the quality of chest radiograph representations. We investigate three types of EHR data, including demographic, scan metadata, and inpatient stay information. We evaluate the multimodal MSN on three publicly available chest X-ray datasets, MIMIC-CXR, CheXpert, and NIH-14, using two vision transformer (ViT) backbones, specifically ViT-Tiny and ViT-Small. In assessing the quality of the representations through linear evaluation, our proposed method demonstrates significant improvement compared to vanilla MSN and state-of-the-art self-supervised learning baselines. In particular, our proposed method achieves an improvement of of 2% in the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) compared to vanilla MSN and 5% to 8% compared to other baselines, including uni-modal ones. Furthermore, our findings reveal that demographic features provide the most significant performance improvement. Our work highlights the potential of EHR-enhanced self-supervised pretraining for medical imaging and opens opportunities for future research to address limitations in existing representation learning methods for other medical imaging modalities, such as neuro-, ophthalmic, and sonar imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supervised training of deep neural networks requires large amounts of quality annotated data1. This is not always straightforward in applications involving clinical tasks, due to the time, cost, effort, and expertise required to collect labeled data2. Self-supervised learning has recently demonstrated great success in leveraging unlabeled data, such as in natural language processing3 and computer vision4. Such frameworks aim to learn useful underlying representations during pretraining, without any labels, which are then used in downstream prediction tasks via supervised linear evaluation.

Considering the state-of-the-art performance of self-supervised pretraining with large unlabeled data compared to end-to-end supervised learning, a plethora of recent applications in healthcare sought to harness the power of self-supervised learning by focusing on a specific type of data, usually a single modality5. For example, Xie et al6. applied spatial augmentations for 3D image segmentation, while Azizi et al7. applied transformations to Chest X-Ray (CXR) images and dermatology images to predict radiology labels and skin conditions, respectively. Zhang et al8. preserved time-frequency consistency of time-series data for several tasks, such as detection of epilepsy, while Kiyasseh et al9. leveraged electrocardiogram signals to learn patient-specific representations for the classification of cardiac arrhythmia.

Self-supervised learning methods learn task-agnostic feature representations using hand-crafted pretext tasks or joint embedding architectures10,11. Hand-crafted pretext tasks rely on the use of pseudo-labels generated from unlabeled data. Examples of such tasks include rotation prediction12, jigsaw puzzle solving13, colorization14, and in-painting15. Joint embedding methods utilize siamese networks16 to learn useful representations by discriminating between different views of samples based on a specific objective function11, without the need for human annotation or pseudo-labels. Joint embedding methods can be further categorized into contrastive and non-contrastive methods, where the latter encompasses clustering, distillation, and information maximization methods11. Contrastive methods learn representations by maximizing the agreement between positive pairs and minimizing the agreement between negative pairs17. Some prominent examples include SimCLR18, contrastive predictive coding17, and MoCo19. Non-contrastive methods focus on optimizing different forms of similarity metrics across the learned embeddings. Examples include BYOL20, SimSiam21, and VICReg11. Although most existing work considers convolutional networks as the backbone of input encoders, recent approaches explore the role of vision transformers (ViT)22for self-supervision, such as DINO23and MSN24. MSN is a state-of-the-art self-supervised learning architecture that operates on the principle of mask-denoising, without reconstruction, as well as transformation invariance with transformers. MSN has limited applications in healthcare-related tasks, and is promising considering its computational scalability.

Self-supervised learning methods have shown great promise in learning representations of different types of medical images, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging2,25,26, optical coherence tomography and fundus photography27,28,29, and endoscopy images30. Several studies investigated self-supervised learning for applications involving CXR images. For example, Sowrirajan et al31., Chen et al32., and Sriram et al33. utilized MoCo19as a pretraining strategy for chest disease diagnosis and prognosis tasks. Azizi et al7. showed that the initialization of SimCLR18during pretraining with ImageNet weights improves downstream performance in CXR classification. Van et al34. explored the impact of various image augmentation techniques on siamese representation learning for CXR.

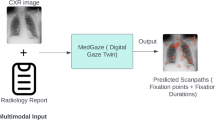

Overview of the multimodal MSN pretraining framework. We use \(x_{ehr}\) as an auxiliary modality during model pretraining. In downstream classification, we freeze \(f_{target}\) and use it as a feature extractor along with a classification head for multi-label image classification. Components of the vanilla MSN are outlined in black.

Medical data is inherently multimodal, encompassing various types of modalities, such as medical images, Electronic Health Records (EHR), clinical notes, and omics35. In clinical practice, health professionals rely on several sources of information including patient history, laboratory results, vital-sign measurements, and imaging exams to make a diagnosis or treatment decisions and to enhance their understanding of various diseases36,37. Mimicking this approach in model training allows the model to learn from the diverse types of information that clinicians use, potentially leading to better representation learning38,39,40. Additionally, EHR data can provide contextual information that enhances the features extracted from imaging data. For example, demographic information can help the model learn age- or gender-specific patterns41,42, while lab results can indicate underlying conditions that affect imaging findings43,44,45. Lastly, according to the principles of multimodal learning, integrating multiple sources of information can lead to richer and more robust representations46,47. By combining EHR data with imaging data, the model can learn complementary features that may not be apparent when using a single data modality45. Consequently, we hypothesize that making use of additional modalities during self-supervised pretraining can improve the quality of representations for downstream classification tasks48.

Some studies investigated the use of other sources of information in designing the self-supervised learning framework for CXR, mostly focusing on vision-language pretraining. Vu et al49. proposed MedAug, which considers patient metadata to generate positive pairs in the MoCo framework19. Tiu et al50. achieved expert-level performance using raw radiology reports associated with CXR as supervisory signals during self-supervised pretraining. Similarly, Zhang et al51. proposed ConVIRT, a self-supervised learning framework that learns representations from paired CXR and textual data. To the best of our knowledge, none of these methods explored the incorporation of static EHR data during self-supervised pretraining, nor did they investigate the use of MSN for CXR. To address these gaps, we specifically focus on MSN with the goal of enhancing chest X-ray representation learning using transformer pretraining with EHR data.

Although there have been significant advancements in self-supervised learning for medical images, several challenges still exist. First, existing methods mainly focus on a single modality, typically medical imaging data, which may not fully capture the complexity of clinical diagnoses that rely on multiple sources of information. Second, there is a lack of research on integrating EHR data in self-supervised learning frameworks, which can provide valuable contextual information to enhance model performance. Third, the potential of Vision Transformers (ViT), especially in a multimodal context, has been significantly less explored in healthcare applications. These gaps highlight the need for novel integrative approaches that combine multimodal data and advanced architectures to enhance representation learning quality and downstream task performance in medical imaging.

In this paper, we propose incorporating EHR data during self-supervised pretraining with a Masked Siamese Network24for CXR representation learning. In summary, our multimodal pretraining framework includes two visual encoders, adopted from the vanilla MSN, one nonimaging encoder for the EHR, and a projection module that fuses the modalities to encode each CXR-EHR pair. We investigated the inclusion of three types of EHR data, including (a) demographic variables, (b) scan metadata, and (c) inpatient stay information. We also aim to explore the effect of incorporating such information on the downstream performance under individual variables, groups, and combinations of the various variables to determine the best performing varaibles. Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We design a multimodal MSN to incorporate EHR data during self-supervised pretraining for CXR, with the goal of improving the quality of learned representations and enhancing downstream classification. This specifically involves the introduction of an EHR encoder and projection head for the multimodal representation of EHR and CXR. We compare our approach with vanilla MSN and compare MSN to other state-of-the-art methods for CXR.

-

We perform a comprehensive evaluation of relevant EHR features, analyzing their individual and combined impact on self-supervised pretraining for downstream classification.

-

We extensively evaluate our proposed approach using three publicly available datasets: MIMIC-CXR52 for pretraining and internal validation, and ChexPert53 and NIH-1454 for external validation across two different backbones including ViT-Small and ViT-Tiny.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology proposed in this study, including the formulation of the problem and a detailed description of the proposed methodology. Section 3 summarizes the experiments performed in this study, including the description of the data set, evaluation schemes, and baseline models, while Section 4 describes the experimental setup for the expermints conducted in this study. Finally, Section 5 presents the results, whereas Section 6 concludes the paper, states the limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

Methods

Problem formulation

Consider \(x_{cxr}\in \mathbb {R}^{h\times w}\), where h and w represent the height and width of the image, a CXR image collected from the patient during his hospital stay, the goal is to predict a set of disease labels \(y_{cxr}\). We assume that each \(x_{cxr}\) is associated with \(x_{ehr} \in \mathbb {R}^{n}\), a vector of static features derived from the patient’s EHR data, where n is the number of variables. We use both modalities to learn the CXR representation within our pretraining framework. An overview of the multimodal MSN architecture for pretraining is shown in Figure 1. The network consists of two components: (i) the visual encoders for CXR, (ii) a multimodal branch that incorporates the EHR data, as described in the following sections.

Masked siamese network

We adopt the MSN24 as the base model for our proposed framework due to its computational scalability and the need for pretraining transformers efficiently. For a given unlabeled input image, the goal is to align the anchor and target views, denoted by \(x^{anchor}_{cxr}\) and \(x^{target}_{cxr}\), respectively. For each image, a random transformation function T(.) is used to generate a set of Manchor views and a single target view. The transformations include image resizing, random resized cropping, and random horizontal flipping with a probability of 0.5, following Sowrirajan et al31. However, we excluded color jittering and Gaussian blurring as the former does not apply to grayscale images, while the latter may distort disease-related information31. Since the views are patchified to serve as input to a ViT, the anchor views are further masked via patch dropping (either random or focal masking as shown in Figure 2), while leaving \(x^{target}_{cxr}\) unmasked. Two encoders, \(f_{anchor}\) and \(f_{target}\), parameterized with a ViT22, are trained to generate the image embeddings. The anchor views are processed by the encoder \(f_{anchor}\), while the target views are processed by the encoder \(f_{target}\) as given in Equation 1. The weights of \(f_{target}\) are updated by an exponential moving average of \(f_{anchor}\).

The [CLS] token of the target embedding \(v_{cxr+}\) is further processed by a projection head \(h^+(.)\) to obtain the final target embedding \(z^+\), while the [CLS] token of the anchor embedding \(v_{cxr}\) is used in the multimodal mapping as described in the next section. MSN does not compute the loss directly on the generated embeddings based on a certain similarity metric. Instead, it utilizes a set of of learnable prototypes \(\textbf{q}\in \mathbb {R}^{n\times k}\), where K is the number of prototypes. The network learns to assign the learned embeddings from the anchor and target branches to the same prototype based on cosine similarity, such that \(p_{i,m}:= \text {softmax}(\frac{z_{i,m} \cdot \textbf{q}}{\tau })\) and \(p_{i}^+:= \text {softmax}(\frac{z_{i}^+ \cdot \textbf{q}}{\tau ^+})\), where \(\tau\) and \(\tau ^+\) are the temperature hyperparameters. The mappings are then used to compute the loss, where the overall loss function is defined using a standard cross-entropy loss \(H(p_i^+, p_{i,m})\) and a mean entropy maximization regularizer \(H (\bar{p})\) following Equation 2:

where B is the batch size, M is the number of anchor views, and \(\lambda\) is the weight of the mean entropy maximization regularizer. The value of \(\bar{p}\) in the regularization term is calculated as presented in Equation 3:

Multimodal pretraining

MSN on its own is designed for representation learning from images only. Instead of solely relying on CXR images, our proposed framework encourages MSN to leverage additional information extracted from the patient’s EHR data. In particular, we introduce three additional modules to the standard MSN architecture to enable EHR leveraging during pretraining. The three modules are EHR encoder denoted as \(f_{ehr}\), fusion module denoted as \(\oplus\) and projection head denoted as g. We illustrate the role of each module as follows:

First, we encode the static EHR data with the EHR encoder \(f_{ehr}\) to learn an EHR representation vector, such that:

We then concatenate (\(\oplus\)) the EHR and CXR latent representations, \(v_{ehr}\) and \(v_{cxr}\). At this stage, there exists dimensionality mismatch between the concatenated representations and \(v_{cxr+}\). To address this, we project the concatenated representation into the same dimensional space of \(v_{cxr+}\) using a linear projection head, denoted as g, resulting in \(v_{fused}\):

Lastly, the fused representation is processed by a projection head h(.) to compute z. Both z and \(z^+\) are used in the clustering of prototypes during pretraining. Overall, this simple procedure learns a joint representation of the EHR data and the anchor embeddings, with the goal of improving the mapping ability of MSN during pretraining.

Downstream classification

After pretraining the encoders \(f_{target}\), \(f_{anchor}\), and \(f_{ehr}\), we use \(f_{target}\) as a feature extractor. We then include a classification model \(f_c\) to predict the image labels:

The main assumption behind our proposed method is that introducing additional data related to the patient or the CXR scan during pretraining would provide the model with valuable contextual information. This information would contribute to enhancing the quality of the learned representations for downstream classification.

Experiments

Dataset

We conducted our experiments using the MIMIC-CXR dataset, which is a publicly available dataset of CXR images52. MIMIC-CXR includes 377,110 chest radiographs gathered from 227,835 studies between 2011 and 2016. Each image is associated with a set of ground-truth labels \({y}_{cxr}\in \mathbb {R}^{14}\) that indicates the presence of any of 14 medical conditions extracted from corresponding radiology reports. The medical conditions are Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Consolidation, Edema, Enlarged Cardiomediastinum, Fracture, Lung Lesion, Lung Opacity, Pleural Effusion, Pneumonia, Pneumothorax, Pleural Other, Support Devices, and No Finding. After pre-processing, the dataset consisted of 376,201 individual CXR images related to 65,152 patients and 82,506 stays.

Pretraining and internal validation

We used MIMIC-IV55, an EHR database associated with MIMIC-CXR, to extract EHR variables related to the CXR images. Table 1 provides a summary of the extracted EHR features, including data types, possible values, and dimensionality. After a thorough investigation of the MIMIC-IV database, we identified three sets of relevant features: patient demographics (\(x_D\)), scan metadata (\(x_{SM}\)), and inpatient stay information (\(x_{SI}\)). For patient demographics, we retrieved patient age (\(x_{age})\) for each specific admission and normalized it using MinMax normalization, as well as patient sex (\(x_{sex}\)) encoded as a one-hot vector. For scan metadata, we extracted the scan view (\(x_{view}\)) and patient position (\(x_{pos}\)) and encoded them as one-hot vectors. The possible values for view are antero-posterior (AP), lateral (L), postero-anterior (PA), or left-lateral (LL), while for patient position the possible values are erect or recumbent. For inpatient information, we defined \(x_{icu}\) and \(x_{mort}\) as binary features indicating whether the patient required intensive care treatment or experienced in-hospital mortality, respectively. In the presence of missing data, we utilize an iterative imputer wrapped with a Random Forest estimator to handle the missingness. We provide a summary of the EHR features distributions in the supplementary Figure S.1. We used MIMIC-CXR and MIMIC-EHR for pretraining and internally validated our proposed method on MIMIC-CXR only. We followed the work of Hayat et al38. to obtain the training, validation, and test splits. We create the splits randomly based on the patient identifier to avoid data leakage from the same patients between splits. The data splits are provided in Table 2.

External validation

We also performed external validation of our pretrained encoders in downstream classification using the ChexPert53 and National Institutes of Health Chest X-Ray Dataset (NIH-14)54 datasets. ChexPert is a publicly available medical imaging dataset composed of 224,316 chest radiographs of 65,240 patients, collected between 2002-2017, including inpatient and outpatient centers. It includes images and associated radiology reports, which were used to generate labels indicating the presence of 14 diseases. We evaluated the pretrained encoder and classifier obtained with MIMIC-CXR on the ChexPert test set since they have the same labels. NIH-14 is a publicly available medical imaging dataset composed of 112,120 frontal-view CXR images of 30,805 patients, collected between 1992-2015. Each image is assigned 14 common disease labels. We follow the same split reported in Irvin et al53. and perform linear evaluation using the NIH-14 training set, since it has different labels from MIMIC-CXR. The data splits are shown in Table 2.

Evaluation protocol

To assess the quality of the learned representations using our proposed pretraining framework, we conducted linear evaluation as the main evaluation protocol following previous work in self-supervised learning11,56,57. We froze the encoder \(f_{target}\) after pretraining, and trained the classification head \(f_c\), which is randomly initialized, with embeddings of the whole training set. We report performance using the Area Under the Receiver Operating characteristic Curve (AUROC) and the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) across all experiments. We report the 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) using the bootstrapping method58. We also performed statistical significance testing by comparing our proposed approach with the best performing baseline using standard student t-test.

Uni-modal self-supervised pretraining baselines

We compared the results of our proposed method with self-supervised and supervised baselines that are transformer-based for a fair comparison:

-

1.

Vanilla MSN24: MSN is a self-supervised learning model that leverages the idea of mask-denoising while avoiding pixel and token-level reconstruction. We trained the vanilla version following the architecture in the original work.

-

2.

DINO23: DINO is a transformer-based architecture that learns representation via knowledge distillation from a teacher backbone to a student backbone without labels.

-

3.

Masked AutoEncoder (MAE)59: MAE is a transformer-based encoder-decoder architecture that learns representation by reconstructing the missing pixels within an input image.

-

4.

Supervised: We train ViT-S and ViT-T in an end-to-end fashion with random and ImageNet60 weight initializations.

We consider Vanilla MSN as the primary baseline for comparison, as our work builds on top of it. Additionally, we use MAE, DINO, and ImageNet as secondary baselines to examine the performance of our proposal relative to other state-of-the-art self-supervised pretraining methods.

In our experiments, we used ViT-Small (ViT-S) as the backbone for our proposed method and the state-of-the-art self-supervised baselines. We also conducted experiments using the ViT-Tiny (ViT-T) backbone. These are smaller versions than the ones defined in Dosovitskiy et al22. and we chose them due to significantly faster training time with comparable performance compared to the original implementation with ViT-Base (ViT-B). For \(f_{ehr}\) we used a single linear layer, we empirically found that a single layer for \(f_{ehr}\) secures stable pretraining, while increasing the number of layers or dimensionality results in unstable pretraining and causes early stopping. For g projection head, we used also a single linear layer to map the fused representation into the same dimensional space of \(v_{cxr+}\).

Overview of experiments

Our experiments are designed to evaluate the impact of incorporating EHR data into the self-supervised pretraining of chest X-ray images using MSN. We investigate the following aspects:

-

1.

The effect of different categories of EHR data on representation learning as well as the downstream performance. These experiments aim at determining the set of EHR features used during pretraining that give the best downstream performance.

-

2.

The performance comparison between different Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones (ViT-Tiny and ViT-Small). The goal of this analysis is to verify the validity of our proposed approach across different backbones.

-

3.

The generalization capability of our multimodal MSN framework across different datasets. The objective of these experiments is to verify the validity of our proposed approach across different datasets.

-

4.

The verification of the quality of the learned representation in our multimodal MSN framework using t-SNE analysis. This analysis targets visually understanding and comparing the quality of the learned representation via our proposed method as compared to vanilla MSN.

Experimental setup

Pretraining setup

We follow the same hyperparameter settings as in the original MSN24, DINO23, and MAE59. Concerning masking, we use a masking ratio of 0.15 for MSN and 0.6 for MAE. We use exponential moving average with a momentum value of 0.996 to update the target encoder in MSN and the teacherencoder in DINO, along with their respective projection heads. We use the AdamW optimizer61 for MSN and the other self-supervised baselines with a batch size of 64. To select the learning rate, we conduct several experiments using different combinations of learning rate and weight decay values. We empirically found that the best learning rate and weight decay values for MSN are \(1e-4\) and \(1e-3\), respectively, while the best values for DINO and MAE are \(1e-5\) and \(1e-4\), respectively. For all pertaining experiments, we employ the cosine annealing method as a learning rate scheduler. We pretrain each model for 100 epochs with early stopping, using a patience of 5 epochs and a minimum delta of \(1e-5\) for the training loss.

To incorporate EHR data in our proposal, we implement both \(f_{ehr}\) and g as linear layers (see Figure 1). We fix the output dimension of \(f_{ehr}\) as 128 and match the output dimension of g to the hidden size D according to the backbone used. For the fusion operator \(\oplus\), we utilize simple concatenation over the first dimension of both \(v_{ehr}\) and \(v_{cxr}\). The design choices regarding \(f_{ehr}\) and g layers is determined empirically during model the developments stage. We found that found that a single linear layer for the f encoder resulted with stable pretraining. Increasing the number of layers or the dimensionality of f led to unstable training and triggered earlier stopping without improved learning. For the the projection layer g, we used a single layer as we simply sought to project the representation to the same dimensional space as \(v^+_{cxr}\).

Downstream classification setup

We use the Adam optimizer62 with a batch size of 64 for all downstream evaluation experiments. For each method evaluation, we perform three experiments with learning rates in [\(1e-3\),\(5e-4\),\(1e-4\)] following Azizi et al7., each with cosine annealing learning rate scheduler. In this setup, we apply early stopping with a patience of 5 epochs if the validation AUROC does not improve by \(1e-4\). Additionally, we conduct two more experiments with learning rates in [\(5e-4\), \(1e-4\)] and use the Reduce on Plateau learning rate scheduler without early stopping. We perform this setup once for linear evaluation and replicate it for fine-tuning experiments, resulting in 10 experiments for each model. We select the best-performing model on the validation set for test set evaluation. The maximum training epochs for all downstream evaluation tasks are set to 50 epochs. For augmentations, we apply random horizontal flip, random affine, and center crop during training, and only center crop during inference. We use ImageNet60 statistics to normalize the CXR images during both training and inference, following the same settings as during pretraining.

General training setup

We summarize the computational requirements utilized for pretraining and evaluation of our proposed method including the hardware setup, training time, computational complexity, and resource utilization. For hardware, all pretraining experiments are conducted using a single Nvidia A100 GPU (80 GB), and downstream evaluation is performed using a single Nvidia V100 GPU (32 GB). It is worth noting that these GPU specifications are not minimum specification requirement, but their usage is mainly based on their availability. However, the large memory capacity and high processing power of these GPUs are critical for efficiently handling the multimodal data and training the ViT backbones within a reasonable time-frame. With respect to training time, pretraining for 100 epochs takes approximately 20 hours and 30 hours to train ViT-T and ViT-S, respectively. The downstream evaluation of the pretrained models requires 2 hours for ViT-T and 5 hours for ViT-S to run experiments for 50 epochs. To optimize resource utilization, we employed automatic mixed-precision63 which significantly reduced the memory footprint and allowed for training larger models on the available hardware. Lastly, the computational complexity of our approach depends on the number of parameters in the ViT backbones, the size of the input data, and the complexity of the multimodal integration.

Results

Linear evaluation results

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the performance results of the linear evaluation experiments using ViT-S and ViT-T, respectively. First for ViT-S, we note that all of the models that incorporate EHR during pretraining achieve a better performance compared to the best performing baseline, vanilla MSN. The improvement is at least \(1\%\) in terms of AUROC and AUPRC, with a maximum improvement of \(2\%\) when incorporating demographic information, 0.751 AUROC with \(x_{sex}\) or \(x_{D}\), compared to 0.731 AUROC with MSN. Additionally, in most experiments where we pretrain with a single EHR feature achieve improvements greater than \(1.5\%\), while pretraining with groups of features yields slightly lower performance improvements. For ViT-T backbone, the results demonstrate that all EHR-based pretraining strategies provide better performance as compared to vanilla MSN. The best performance gained under ViT-T is achieved using \(x_{pos}\) which gives AUROC of 0.729, that is \(2.1\%\) higher than vanilla MSN. Further, both \(x_{sex}\) and \(x_{age}\) achieve comparable performance to \(x_{pos}\) (0.728 AUROC). Also, The same conclusion holds for ViT-T as compared to ViT-S regarding performance gain with individual variables versus groups or combinations.

Moreover, our proposed strategies demonstrate a significant improvement using both ViT-S and ViT-T backbones as compared to state-of-the-art self-supervised learning baselines, specifically MAE and DINO, as well as the supervised ImageNet-initialized baseline, reaching an improvement of \(10\%\) compared to the worst performing model. In summary, the results of linear evaluation demonstrate that our approach, which incorporates EHR data during pretraining, enhances the quality of the learned representations and downstream performance in a multi-label disease classification task, surpassing both the vanilla MSN and other baselines.

For the sake of completeness we also report in the Supplementary Table S.2 (ViT-S) and Table S.3 (ViT-T) the results of a secondary evaluation protocol by fine-tuning under low data regimes including \(1\%\), \(5\%\), and \(10\%\) of the full training set. In this setting, we trained both the pretrained encoder \(f_{target}\) and the classification head \(f_c\) with the training set. We note that the results are on par with vanilla MSN, which is expected since fine-tuning dilutes the effects of incorporating EHR during pretraining.

External validation results

Table 5 and Table 6present the external validation results for linear evaluation of our proposed methods using the ViT-S and ViT-T backbones, respectively, on the ChexPert53and NIH-1454 datasets. The results indicate that our multimodal pretraining enhances the robustness of self-supervised models, resulting in higher validation scores and improved performance compared to vanilla MSN in most scenarios using both ViT-S and ViT-T backbones. In the best scenario, Our proposed method achieves an AUROC score of 0.801 on the CheXpert test set under \(x_{view}\) compared to vanilla MSN, which achieves 0.770 using the ViT-S backbone. For the NIH dataset, the best performance is achieved under \(x_{SI}\) features with an AUROC score of 0.738 compared to 0.699 for vanilla MSN. Additionally, our proposed method demonstrates significantly higher performance with respect to other EHR features in comparison with vanilla MSN. We also observe similar behavior with respect to the ViT-T backbone, which achieves a performance gain of \(3\%-4\%\) (AUROC) in the best scenario. We observe better performance improvements in the NIH-14 dataset, since its training set was used to train the linear evaluation classifier, compared to off-the-shelf evaluation with CheXpert. In general, the external validation results demonstrates the generalizability of our proposed method.

Embedding visualization via t-SNE. We plot the resulting embeddings obtained via t-SNE for (a): Vanilla MSN (best performing baseline) (b): MSN\(+ x_{sex}\) (best performing proposed variant) (c): MSN\(+ x_{D}\) (best performing proposed variant) (d): MSN\(+ x_{D+SM+SI}\) (worst performing proposed variant). The first column depicts the clusters of the four most prevalent diseases in the dataset, the second column corresponds to the second four most prevalent diseases, and the last column represents the four least prevalent diseases.

T-SNE analysis results

We applied t-SNE to a subset of samples with a single label in the training set (n=68,000) of MIMIC-CXR for the ease of interpretability, considering the challenge of visualizing multi-label samples in the latent space. Figure 3 visualizes the embeddings obtained with vanilla MSN (baseline), MSN\(+ x_{sex}\), MSN\(+ x_{D}\), and MSN\(+ x_{D+SM+SI}\) for the ViT-S backbone. As MSN learns image representations by comparing cluster assignments of masked and unmasked image views, the quality of clustering is essential for downstream task performance. Based on our qualitative assessment, we observe that the clustering quality is enhanced using MSN\(+ x_{sex}\), MSN\(+ x_{D}\) and MSN\(+ x_{D+SM+SI}\) compared to vanilla MSN. More specifically, the clusters of the best performing approaches (MSN\(+ x_{sex}\), and MSN\(+ x_{D}\)) show denser clusters, with lower intra-cluster distance and larger inter-cluster distances, which is typically related to a better clustering quality in the embedding space. We hypothesize that this enhanced clustering quality yields an improved downstream performance.

Visualization of attention heat maps

Figure 4 displays attention maps generated from the last layer of the ViT-S backbone for single label examples. As illustrative cases, we compare our best-performing variant, MSN+\(x_{sex}\), against vanilla MSN model across the labels: Edema, No findings, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia, and Supporting devices. For edema, both models focus their attention on the lung area to make their predictions. However, while the vanilla MSN primarily focuses on the central thoracic region, MSN+\(x_{sex}\) covers a broader area of the lung, leading to a more confident prediction. Similarly, for the no finding label, MSN+\(x_{sex}\) examines the entire CXR scan to rule out any medical conditions, resulting in a high probability score of 0.984. In contrast, the vanilla MSN primarily focuses on the central region of the scan with only peripheral attention to the lung boundaries. For pleural effusion, both the vanilla MSN and MSN+\(x_{sex}\) models report similar prediction scores of 0.851 and 0.901, respectively, while focusing on the pleural space region. Although MSN+\(x_{sex}\) covers a broader area in this region to ensure that no potential pleural effusion is missed, vanilla MSN remains more focused on the central region of the scan, as in previous cases. In the case of pneumonia prediction, MSN+\(x_{sex}\) concentrates on lung tissues, with particular emphasis on the right side where opacity is more clearly evident. In contrast, MSN focuses on the central region, which may cause it to miss the condition and fail to detect it. Lastly, for support devices, MSN+\(x_{sex}\) attends nearly all regions where tubes are present, whereas vanilla MSN focuses specifically on regions with a dense appearance of tubes. Overall, the predictions made by MSN+\(x_{sex}\) rely on broader and more relevant regions for disease detection, while those made by vanilla MSN are more focused on the central area of the scan, potentially missing important details for detecting clinical conditions.

Discussion

In this paper, we propose the incorporation of EHR data during self-supervised pretraining for CXR representation learning, with the aim of improving performance in downstream classification. We present our proposed approach as an enhanced version of an existing self-supervised learning method, MSN24, by including clinical imaging-related patient EHR data during pretraining. We conducted extensive experiments to evaluate the impact of different categories of EHR data on the quality of learned representations and downstream performance. Additionally, we provided a comprehensive analysis of the performance of different Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones within our multimodal self-supervised framework. We also comprehensively evaluated our proposed approach on the MIMIC-CXR dataset (internal validation), and two datasets for external validation, ChexPert and NIH-14.

Our results demonstrate that the integration of EHR metadata during pretraining with MSN significantly improves performance in the downstream linear evaluation protocol. We also observe that, in general, the inclusion of a single EHR feature yields better quality embeddings compared to pretraining with combinations of EHR features, as shown by the t-SNE embeddings in Figure 3. In this regard, an interesting finding in this study is that single EHR features improve performance, but multiple EHR features impair performance. While this may seem counter intuitive and one would expect that adding more features could enhance clustering, we did not observe such behavior. In this regard, an important consideration is that it is not completely guaranteed that adding more EHR features would yield an improved performance. We gradually incorporated the EHR data in our experiments to explore how the inclusion of additional features would affect pretraining and used t-SNE to assess how the learned representations differed amongst the various combinations of EHR data. The t-SNE results, plotted in Figure 3, may, in fact, explain this observation. In most cases, the inclusion of a single EHR feature yields better quality of embeddings compared to pretraining with combinations of several EHR features. In particular, based on the t-SNE embedding, we observe that all features (i.e., MSN\(+ x_{D+SM+SI}\)) did not enhance clustering to the same degree as some individual variables (e.g., MSN\(+ x_{sex}\)) or groups (e.g., MSN\(+ x_{D}\)) did. As a result, the performance of linear evaluation in downstream tasks was higher for those models with better clustering quality, such as MSN\(+ x_{sex}\) and MSN\(+ x_{D}\). We plan to thoroughly investigate this behavior in future work.

In addition, our proposed method shows superior performance compared with other state-of-the-art self-supervised baselines, including DINO23and MAE59, as well as fully supervised baselines pretrained with ImageNet60. Our extensive evaluation highlights that our proposed approach generalizes well to external validation datasets, significantly outperforming vanilla MSN in various settings for CheXpert and in all cases for the NIH-14 dataset. A relevant insight derived from our extensive experimentation using single features and combinations of them is that it is not guaranteed that the addition of more EHR features leads to improved performance. We hypothesize that such behavior could be attributed to feature interactions, which is an area of future work. Another possible cause of such behavior is the sparsity of the EHR vector under feature combinations, which may hurt the quality of the learned representations. A thorough investigation of the causes behind this behavior is out of the scope of the present paper and will be addressed in our future work.

Our experiments also showed MAE performs poorly as compared to ImageNet as well as all other baselines including ours despite being a widely-used self-supervised learning framework. Thus, we want to note that while typically self-supervised approaches may outperform supervised baselines on ImageNet, it is not guaranteed that a self-supervised method for a specific dataset outperforms an ImageNet pre-trained supervised baseline64. To ensure the correctness of our results, we conducted a comprehensive experimentation on MAE pretraining using using different settings, hyper-parameters, and learning rates. Despite the comprehensive set of settings evaluated, we obtained similar AUROC performances for all experiments, ranging in [0.62-0.65], and reported the best setting in the paper. We hypothesize that the lower performance of MAE in comparison with ImageNet performance may have been impacted by the dataset preprocessing pipeline and intrinsic characteristics, weight initialization and downstream task inherent challenges as a multi-label task.

Lastly, the main objective of this work is to investigate whether multimodal self-supervised pretraining would improve the quality of representations, in the context of MSN specifically due to its unique architecture, and downstream task performance. While we believe that stronger baselines may produce a better comparison, such baselines do not exist in the literature. In addition, state-of-the-art methods (e.g., MAE, DINO, MSN) differ significantly, thus affecting the feasibility of implementing our proposal across architectures. For instance, the nature of MAE as an autoencoder-based architecture poses a question on how and where to incorporate the EHR data, i.e., whether it should be on the input level, latent representation level, or reconstruction level. In this regard, the strong baseline for our proposal is the vanilla MSN architecture. Hence, incorporating EHR in such frameworks requires more sophisticated methodological modifications, which we believe our work may open doors for.

Visualization of predictions using attention heat maps. Examples of attention maps generated from the last layer of the ViT-S backbone along with the prediction scores. We compare predictions across five labels: Edema, No finding, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia, and Support devices. (a) The original CXR image. (b) The attention maps generated by the vanilla MSN (best-performing baseline). (c) The attention maps generated by MSN\(+ x_{sex}\) (best-performing proposed variant).

Limitations

Despite the performance improvements shown by our framework during linear evaluation, our approach has some limitations. First, our approach did not show significant improvements during end-to-end fine-tuning. That is, it performed on-par with vanilla MSN, or slightly lower in the worst scenario as shown in the additional results in supplementary Tables S.2, S.3, S.4, and S.5. We hypothesize that fine-tuning the target encoder without the EHR data dilutes the impact of incorporating it during pretraining. Specifically, the learned representations during the pretraining stage (with EHR data) are updated during fine-tuning (without EHR data), which affects the quality of the representations. We aim to address this limitation in our future work, where the EHR data is incorporated during both linear evaluation and fine tuning, rather than solely during pretraining for a fair comparison. Furthermore, we only tested our proposed methodology with a transformer-based self-supervised learning method. In future work, we will explore its applicability to other self-supervised learning architectures and generalization as a framework for other medical imaging datasets and clinical prediction tasks. Another limitation is that our proposed approach has only been tested using medical imaging datasets associated with EHR databases, such as MIMIC-CXR and MIMIC-IV. This restricts its applicability to datasets consisting of medical images. Lastly, we tested our proposed methodology using a single self-supervised learning method, MSN. we believe that our current proposal paves the way for advancing the field of multimodal pretraining with medical images and EHR data.

Future research

As a future research direction, this work can be further improved by exploring the incorporation of additional EHR data types, such as lab results, clinical notes, and medication records, to further enhance the quality of learned representations. Moreover, assessing the performance of our approach across varying levels of data availability, particularly in scenarios where EHR data is scarce or incomplete, would offer valuable insights into its robustness and adaptability. Another avenue for research could involve extending our proposed method to other medical imaging modalities, such as CT, MRI, and ultrasound, to broaden its impact. Additionally, testing our proposed method using different self-supervised learning frameworks, such as DINO and MAE, would increase the validity of our approach. Further, investigating the interpretability of the learned representations could offer clinicians valuable insights and enhance the practical applicability of our method in clinical settings. Finally, developing strategies to optimize the computational efficiency of our multimodal framework, such as model compression techniques or more efficient data integration methods, would be beneficial for practical deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Code availability

We make our codebase publicly accessible following the guidelines for reproducibility in research65 on GitHub at: https://github.com/nyuad-cai/CXR-EHR-MSN

Change history

27 September 2024

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the author name Alejandro Guerra-Manzanareswas incorrectly indexed. The original Article has been corrected.

References

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Taleb, A. et al. 3d self-supervised methods for medical imaging. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 18158–18172 (2020).

Lan, Z. et al. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.11942 (2019).

Jing, L. & Tian, Y. Self-supervised visual feature learning with deep neural networks: A survey. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 43, 4037–4058 (2020).

Shurrab, S. & Duwairi, R. Self-supervised learning methods and applications in medical imaging analysis: A survey. PeerJ Computer Science 8, e1045 (2022).

Xie, Y., Zhang, J., Liao, Z., Xia, Y. & Shen, C. Pgl: prior-guided local self-supervised learning for 3d medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.12640 (2020).

Azizi, S. et al. Big self-supervised models advance medical image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 3478–3488 (2021).

Zhang, X., Zhao, Z., Tsiligkaridis, T. & Zitnik, M. Self-supervised contrastive pre-training for time series via time-frequency consistency. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.08496 (2022).

Kiyasseh, D., Zhu, T. & Clifton, D. A. Clocs: Contrastive learning of cardiac signals across space, time, and patients. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 5606–5615 (PMLR, 2021).

Kinakh, V., Taran, O. & Voloshynovskiy, S. Scatsimclr: self-supervised contrastive learning with pretext task regularization for small-scale datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 1098–1106 (2021).

Bardes, A., Ponce, J. & LeCun, Y. Vicreg: Variance-invariance-covariance regularization for self-supervised learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.04906 (2021).

Gidaris, S., Singh, P. & Komodakis, N. Unsupervised representation learning by predicting image rotations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.07728 (2018).

Noroozi, M. & Favaro, P. Unsupervised learning of visual representations by solving jigsaw puzzles. In European conference on computer vision, 69–84 (Springer, 2016).

Zhang, R., Isola, P. & Efros, A. A. Colorful image colorization. In European conference on computer vision, 649–666 (Springer, 2016).

Pathak, D., Krahenbuhl, P., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Efros, A. A. Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2536–2544 (2016).

Bromley, J., Guyon, I., LeCun, Y., Säckinger, E. & Shah, R. Signature verification using a” siamese” time delay neural network. Advances in neural information processing systems6 (1993).

Van den Oord, A., Li, Y. & Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv e-prints arXiv–1807 (2018).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International conference on machine learning, 1597–1607 (PMLR, 2020).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 9729–9738 (2020).

Grill, J.-B. et al. Bootstrap your own latent: A new approach to self-supervised learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.07733 (2020).

Chen, X. & He, K. Exploring simple siamese representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 15750–15758 (2021).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Caron, M. et al. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 9650–9660 (2021).

Assran, M. et al. Masked siamese networks for label-efficient learning. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 456–473 (Springer, 2022).

Jamaludin, A., Kadir, T. & Zisserman, A. Self-supervised learning for spinal mris. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, 294–302 (Springer, 2017).

Zhuang, X. et al. Self-supervised feature learning for 3d medical images by playing a rubik’s cube. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 420–428 (Springer, 2019).

Holmberg, O. G. et al. Self-supervised retinal thickness prediction enables deep learning from unlabelled data to boost classification of diabetic retinopathy. Nature Machine Intelligence 2, 719–726 (2020).

Hervella, Á. S., Ramos, L., Rouco, J., Novo, J. & Ortega, M. Multi-modal self-supervised pre-training for joint optic disc and cup segmentation in eye fundus images. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 961–965 (IEEE, 2020).

Li, X. et al. Rotation-oriented collaborative self-supervised learning for retinal disease diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (2021).

Ross, T. et al. Exploiting the potential of unlabeled endoscopic video data with self-supervised learning. International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery 13, 925–933 (2018).

Sowrirajan, H., Yang, J., Ng, A. Y. & Rajpurkar, P. Moco pretraining improves representation and transferability of chest x-ray models. In Heinrich, M. et al. (eds.) Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, vol. 143 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 728–744 (PMLR, 2021).

Chen, X., Yao, L., Zhou, T., Dong, J. & Zhang, Y. Momentum contrastive learning for few-shot covid-19 diagnosis from chest ct images. Pattern recognition 113, 107826 (2021).

Sriram, A. et al. Covid-19 prognosis via self-supervised representation learning and multi-image prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.04909 (2021).

Van der Sluijs, R., Bhaskhar, N., Rubin, D., Langlotz, C. & Chaudhari, A. S. Exploring image augmentations for siamese representation learning with chest x-rays. In Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, 444–467 (PMLR, 2024).

Kline, A. et al. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: A scoping review. npj Digital Medicine 5, 171 (2022).

Cui, M. & Zhang, D. Y. Artificial intelligence and computational pathology. Laboratory Investigation 101, 412–422 (2021).

Xu, K. et al. Multimodal machine learning for automated icd coding. In Machine learning for healthcare conference, 197–215 (PMLR, 2019).

Hayat, N., Geras, K. J. & Shamout, F. E. Medfuse: Multi-modal fusion with clinical time-series data and chest x-ray images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.07027 (2022).

Stahlschmidt, S. R., Ulfenborg, B. & Synnergren, J. Multimodal deep learning for biomedical data fusion: a review. Briefings in Bioinformatics 23, bbab569 (2022).

Venugopalan, J., Tong, L., Hassanzadeh, H. R. & Wang, M. D. Multimodal deep learning models for early detection of alzheimer’s disease stage. Scientific reports 11, 3254 (2021).

Mauvais-Jarvis, F. et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. The Lancet 396, 565–582 (2020).

Adams, A. et al. The influence of patient’s age on clinical decision-making about coronary heart disease in the usa and the uk. Ageing & society 26, 303–321 (2006).

Leslie, A., Jones, A. & Goddard, P. The influence of clinical information on the reporting of ct by radiologists. The British journal of radiology 73, 1052–1055 (2000).

Cohen, M. D. Accuracy of information on imaging requisitions: does it matter?. Journal of the American College of Radiology 4, 617–621 (2007).

Huang, S.-C., Pareek, A., Seyyedi, S., Banerjee, I. & Lungren, M. P. Fusion of medical imaging and electronic health records using deep learning: a systematic review and implementation guidelines. NPJ digital medicine 3, 136 (2020).

Baltrušaitis, T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 41, 423–443 (2018).

Ngiam, J. et al. Multimodal deep learning. In Proceedings of the 28th international conference on machine learning (ICML-11), 689–696 (2011).

Krishnan, R., Rajpurkar, P. & Topol, E. J. Self-supervised learning in medicine and healthcare. Nature Biomedical Engineering 6, 1346–1352 (2022).

Vu, Y. N. T. et al. Medaug: Contrastive learning leveraging patient metadata improves representations for chest x-ray interpretation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.10663 (2021).

Tiu, E. et al. Expert-level detection of pathologies from unannotated chest x-ray images via self-supervised learning. Nature Biomedical Engineering 6, 1399–1406 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Jiang, H., Miura, Y., Manning, C. D. & Langlotz, C. P. Contrastive learning of medical visual representations from paired images and text. In Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, 2–25 (PMLR, 2022).

Johnson, A. E. et al. Mimic-cxr-jpg, a large publicly available database of labeled chest radiographs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.07042 (2019).

Irvin, J. et al. Chexpert: A large chest radiograph dataset with uncertainty labels and expert comparison. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 33, 590–597 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Chestx-ray8: Hospital-scale chest x-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2097–2106 (2017).

Johnson, A. E. et al. Mimic-iv, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Scientific data 10, 1 (2023).

Garrido, Q., Balestriero, R., Najman, L. & Lecun, Y. Rankme: Assessing the downstream performance of pretrained self-supervised representations by their rank. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10929–10974 (PMLR, 2023).

Huang, L., Zhang, C. & Zhang, H. Self-adaptive training: Bridging supervised and self-supervised learning. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence (2022).

Puth, M.-T., Neuhäuser, M. & Ruxton, G. D. On the variety of methods for calculating confidence intervals by bootstrapping. Journal of Animal Ecology 84, 892–897 (2015).

He, K. et al. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 16000–16009 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 248–255 (Ieee, 2009).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 (2017).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Micikevicius, P. et al. Mixed precision training. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.03740 (2017).

Verma, A. & Tapaswi, M. Can we adopt self-supervised pretraining for chest x-rays? arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12931 (2022).

Simkó, A., Garpebring, A., Jonsson, J., Nyholm, T. & Löfstedt, T. Reproducibility of the methods in medical imaging with deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.11146 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This article is supported by Tamkeen under the NYU Abu Dhabi Research Enhancement Fund, the NYUAD Center for AI & Robotics (CG010), Center for Interacting Urban Networks (CG001), and Center for Cyber Security (G1104). We would also like to thank Billy Sun for his contributions in the early phase of the research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and A.G.M. designed the computational framework and extracted the relevant features for the study. S.S carried out model training and evaluation. A.G.M. contributed to the interpretation of the results. F.E.S. supervised all elements of the project. S.S. and A.G.M. contributed towards drafting the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shurrab, S., Guerra-Manzanares, A. & E. Shamout, F. Multimodal masked siamese network improves chest X-ray representation learning. Sci Rep 14, 22516 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74043-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74043-x

This article is cited by

-

Multimodal vision-language models in chest x-ray analysis: a study of generalization, supervision, and robustness

Biomedical Engineering Letters (2025)