Abstract

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27 guidelines are the recommended and most commonly used protocols for broth microdilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. However, these guidelines are limited to the use of 96-well assay plates, limiting assay capacity. With the increased risk of fungal resistance emerging in the community, it is important to have alternative protocols available, that offer higher throughput and can screen more than eight to ten potential antifungal compounds per plate. This study presents an optimised broth microdilution minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method for testing the susceptibility of yeasts in an efficient high throughput screening setup, with minimal growth variability and maximum reproducibility. We extend the M27 guidelines and optimise the conditions for 384-well plates. Validation of the assay was performed with ten clinically used antifungals (fluconazole, amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, posaconazole, voriconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole, caspofungin diacetate, anidulafungin and micafungin) against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistant fungal infections have increased considerably in the last decade, leading to the World Health Organisation (WHO) to issue a fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action1. They are caused by nosocomial organisms and opportunist pathogens. Candida albicans is the most prevalent fungal species present in the human microbiota, it colonises mucosal surfaces, such as the gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity, reproductive tract and skin of healthy adults2. However, variations in the host immune response or resident microbiota can enable C. albicans to overgrow and cause infection3. C. albicans is recognised as one of the most frequent human pathogens discovered in immunocompromised patients, as a consequence of advanced age, infection or immunosuppressive therapy4,5, and is one of four pathogens in the ‘critical priority group’ in the 2022 WHO fungal report. In addition to C. albicans, other species such as Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis (WHO ‘high priority’), Candida parapsilosis (WHO ‘high priority’), Candida krusei and Candida auris (WHO ‘critical priority’) can cause debilitating and recurring infections in these mucosal surface areas5,6. In recent years, there has been an increase of emerging Candida infections reported worldwide, caused by species such as Candida guilliermondii, Candida kefyr, Candida rugosa, Candida dubliniensis, and Candida famata7. The National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNISS) has reported Candida species as one of the most common nosocomial bloodstream pathogen with a high estimated mortality rate (45%), with the high mortality most likely due to ineffective diagnostic techniques, inappropriate antifungal treatment7 and increasing antifungal resistance.

Cryptococcus neoformans (WHO ‘critical priority’) is an environmental microbe that lives in a yeast-like form, and is the pathogen responsible of causing life-threatening infections like cryptococcosis and meningoencephalitis. People are infected with C. neoformans from the environment, most likely by inhalation of infectious particles8. In healthy hosts, the primary infections can be asymptomatic. Serious illness arises in cases of deficiency or absence of intact cell-mediated immunity, and typically infections are found in immunocompromised patients9, people undergoing prolonged treatment with corticosteroids10 or immunosuppressive therapies and patients with advanced AIDS11,12. Some infections can be caused by reactivation of latent infection. C. neoformans has well-defined virulence factors, as well as the capability to grow at 37°C, to form a polysaccharide capsule and to produce spores13. It is also able to “replicate intracellularly and can escape the intracellular state without being killed or killing the host cell”9. Cryptococcus is the most common cause of meningitis in adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated 181,000 deaths globally in 201412, representing 15% of AIDS related deaths due to cryptococcal meningitis.

C. albicans and C. neoformans have developed a set of strategies to survive in hostile hosts. Antifungal resistance is based on adaptation mechanisms in the presence of toxic drugs, and include: mutations of drug targets reducing affinity for the drug, overexpression of the targeted protein, expression of an efflux system, degradation of the drugs and finally pleiotropic drug responses7,14. The treatment for infections caused by C. albicans and C. neoformans predominantly relies on a single class of antifungals known as azoles. The worldwide deployment of azoles, combined with the fungistatic nature of these drugs has contributed to the rise of azole resistance in clinical isolates14. Fluconazole resistant C. neoformans strains have been the most common, arising from AIDS patients undergoing long-term azole therapy10. The clinical relevance of these strains has contributed to the urgency to find new antifungals that can target these strains.

Drug discovery projects are often initiated with a high throughput screening campaign, testing hundreds of thousands to millions of chemically diverse compounds. In order to increase the number of antifungals available in the clinic, it is important to improve the throughput of Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AST) available15 and scale testing to a high throughput screening format to increase the chances of finding more efficient and diverse therapies. The guidelines of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) describe methods to measure antimicrobial susceptibility for Candida and Cryptococcus spp in 96 well plates16, suggesting Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 media with MOPS (3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid) buffer incubated at 35 °C for 48 h for C. albicans and 72 h for C. neoformans. However, other committees such as the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)17 and several publications have proposed different conditions. The suggestions include different conditions for temperature (30 °C and 35 °C), agitation and static conditions, different inoculum preparation and initial inoculum density (103, 104, and 105 CFU/mL)15, alternative media17, and different incubation times18. It is worth noting that both CLSI and EUCAST provide guidelines which are primarily aimed to test the susceptibility of new clinical isolates against known antimicrobials, and not so much for testing novel compounds against known isolates, in a high throughput screening approach in which generally tests single concentration for primary screening and dose response testing only for confirmational screening.

In this study we compared conditions from the CLSI guidelines with conditions described in the literature, such as alternative temperature, media and incubation time, and we applied them to a 384 well plate format for high throughput screening. The study was able to select optimal conditions for the screening against C. albicans and C. neoformans, in 384 well plates with absorbance readout, as measured by optimal growth and by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) profile against a panel of antifungals.

Results

Growth curves in 384 well plates

Both strains, C. albicans (ATCC 90028) and C. neoformans (ATCC 208821), were suspended and diluted to a final concentration of 2.5 × 103 CFU/mL in fresh Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) broth and RPMI-1640 with MOPS Medium. The suspension was added to polystyrene (PS) and non-binding surface polystyrene (NBS) 384 well plates and placed in an incubator at 30 °C and 35 °C. The growth of the yeast was thereby measured in two ways, by measuring the turbidity of each well by an absorbance at a wavelength of 630 nm (OD630), and by taking samples from the wells and counting the colony forming units (CFU) on Yeast Extract-Peptone Dextrose (YPD) agar plates. Both measurements were taken at 0, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h time points.

The CFU/mL counts displayed very little differences for both fungal species, when using either YNB or RPMI as growth media. In contrast, the OD630 readouts using the same growth conditions exhibited substantial differences between the two media. For both species, using the YNB media resulted in higher OD630 reads compared to RPMI.

Spectrometric turbidity measurement is a fast and simple surrogate method to measure antimicrobial growth, allowing the scale up of growth inhibition assays to be conducted as high throughput screening in 96 or 384 well microtiter plates without the need for manual growth/no-growth assessment. The method is, however, dependent on the specific assay setup, including labware, final test volume and absorbance reader. To exclude possible effects from the labware, all assays were repeated in standard polystyrene (PS) 384-well plates (Appendix Figs. 1 and 2), giving similar results as when using the NBS 384-well plates.

A further limitation of measuring antimicrobial growth by absorbance is that, the linearity of turbidity is limited to a narrow range of microbial CFU. For bacteria such as E. coli, OD600 values of 0.1 and 1.0 correspond to a narrow range of 108 and 109 CFU/mL, with small variations between different experimental setup. Similarly, for fungi such as C. albicans, OD630 values of 0.1 and 1.0 correspond to 107 and 108.5 CFU/mL19. In this sense, the two-fold difference in OD630 values seen between the YNB and RPMI media would correspond to a CFU/mL difference equivalent to 2 × 107 to 4 × 107, which is close to the experimental error of the CFU measurement. In addition, different media and plate surfaces will also affect the morphology of the fungi, leading to different turbidity values at similar CFU concentrations20,21.

In the context of high throughput screening for growth inhibition, the quality of the screen is not such much defined by the absolute measurement of CFU/mL, but by the separation between growth (> 107 CFU/mL) and no growth (< 103–105 CFU/mL, depending on the limit of detection). The Z’-factor is thereby used as a quality control of the assay performance, calculated as the ratio between 3 times the sum of variation of positive and negative controls, and the difference between positive and negative controls22.

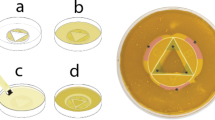

Edge effect in 384 well plates

As 384-well plates have an elevated risk to introduce edge effects in growth due to reduced well volumes (100 µL in standard 96 well plate, 50 µL in 384 well plate), we monitored the edge effect from the growth curve experiments, by calculating the average percentage OD630 values of the edge wells compared to the wells in the middle (Appendix Formula 1 and 2). As Fig. 1 shows, the edge effect was more prominent for C. neoformans than C. albicans. But more surprisingly, the edge effect was mainly dependent on the plate type. Even though the overall growth was similar between the plate types, the PS plates displayed a noticeably higher edge effect for both species. The non-binding surface (NBS) plates displayed a low average edge effect of -3.6% and 3.9% for C. albicans and C. neoformans respectively. These edge effects are within the variations of the wells in the middle, with average Z-scores for the edge wells at 0.38 and 0.42, for C. albicans and C. neoformans respectively (Appendix Table 2). In comparison, when using PS plates the average edge effect was much higher, with 14.9% (Z-Score: 0.71) and 50.7% (Z-Score: 2.71) of additional growth for C. albicans and C. neoformans respectively. For C. neoformans these edge wells lay outside the 99% confidence interval and are classified as significant outliers.

For high throughput screening against C. neoformans using the NBS plate would provide a significant performance improvement for either media, while against C. albicans NBS plates would be preferred over PS plates, as long as YNB media is used.

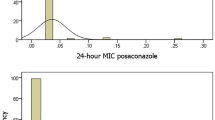

Antifungal susceptibility testing in 384-well plates

The CLSI standard for antifungal susceptibility test has facilitated the establishment of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints for a number of antifungals, such as fluconazole, amphotericin, itraconazole, voriconazole, and against a number of Candidaspp sppspecies. To validate our high throughput method for the measurement of MIC values, we conducted dose response screens of several antifungals against both strains, using YNB and RPMI at 35 °C, and using different incubation times (36, 48 and 72 h).

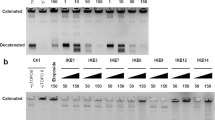

After incubation, optical density was measured at 630 nm (OD630) for C. albicans growth. For C. neoformans we initially measured OD630, which however resulted in poor assay performance parameters with Z’-factor at an average of only 0.32. To improve the assay performance we conducted the assay with the addition of resazurin (final concentration of 0.01%) after incubation and the measurement of the difference in optical density between 570 and 600 nm (OD570 − 600) resulting in an improved average Z’-factor of 0.64. Any reported MIC assay against C. neoformans in YNB was conducted with the addition of resazurin (Table 1). We determined the MIC for each antifungal compound by calculating the percentage of inhibition of each well using media only as negative (100% inhibition) and fungi only as positive control (0% inhibition), and classifying active from non-active wells by using a threshold of 80% inhibition (Tables 1 and 2). For MIC2 a threshold of 50% inhibition was used (Appendix Tables 3 and 5) to represent the half activity equivalent to CLSI score 2.

Most of the antifungals tested against C. albicans and C. neoformans were within the range of expected values, obtained from the literature, in both medias. An exception was caspofungin which, due to its lipophilic chemical structure, had better activity in NBS plates than PS plates (literature values are primarily in PS plates). We have previously described the effect of NBS plates on the antibacterial MIC of some antibiotics23. Furthermore, the CLSI M60: Performance standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts reports significant variability in results of in vitro testing of caspofungin MIC between laboratories24. The MIC of ketoconazole against C. neoformans ATCC 208821 H99 in YNB were higher than the reference MIC. Other papers have suggested the same outcome, in which higher ketoconazole MIC results were observed against C. neoformans25,26. An additional MIC was done using the same methodology with PS plates and YNB media to validate NBS results and also chosen conditions (Appendix Tables 4 and 6 ). Comparison of MIC results is limited due to the lack of literature data available for the two strains used. The CLSI M60 Performance standards only provides MIC values for amphotericin B, fluconazole, and 5-flucytosine, against C. albicans ATCC 90028. Further, the CLSI MIC values were determined using the broth macrodilution method, rather than the broth microdilution method. Since 5-flucytosine is a prodrug, used in combination with amphotericin B for treatment of cryptococcosis, there are limited reference MIC values for the drug alone against C. neoformans27.

High throughput screening performance

As part of the Community for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery (COADD)39,40, we tested a library of more than 300,000 compounds for antifungal activity, using these optimised assay conditions. The assay has been performed on over 5,500 NBS 384-well plates. The assay against C. albicans had a very good and consistent assay performance, with an average Z’-Factor of 0.94 (Stdev = 0.08; 2862 plates) and a rejection rate of 2.2% (64 plates) due to low Z’-Factor’s (< 0.25) or inconsistency in automatic dispensing of either compound solution or fungal broth. For the assay against C. neoformans the performance was slightly lower, displaying more variations, with an average Z’-Factor of 0.76 (Stdev = 0.16; 2701 plates), however with similar low rejection rate of 2.8%.(79 plates).

Discussion

Incubation time

The CLSI M27 guidelines recommend taking note of the difference in end point readings, since the difference between readings at 24 and 48 h may be more clinically relevant for some Candida strains, hence this study tested 24, 36 and 48 h incubation for C. albicans. In our experiments, there was no notable difference in the MIC values between these incubation periods. However, the extent of the OD630 values increased notably from 24 to 36 h while remaining constant for the period from 36 to 48 h, with only small increase in the CFU/mL counts (Fig. 2). Based on these observations, we selected the 36 h time point, close to the end of the exponential phase, as the optimum incubation period for C. albicans.

Figure 3 shows that C. neoformans is in exponential phase even after 72 h of incubation according to the OD630 readout, even though the CFU/mL counts do not differ significantly after 36 h incubation time. Visual inspection of the 384-well plates after 72 h incubation indicated a reduction of the liquid media by around 50% through evaporation. Based on these results, 36 h incubation time was chosen for high throughput antifungal screening, as this showed an acceptable evaporative media loss of around 15%, but still produced a large enough difference in OD between positive and negative controls to determine accurate inhibition values for single concentration primary screening.

Media

The results for C. albicans (Table 2) high throughput antifungal screening showed a comparable range of MIC values using all tested medias, however YNB had more consistent values across all replicates. Additionally, YNB had significant higher OD630 readouts, providing a larger difference between positive and negative controls and more statistical significance to the calculation of inhibition .

C. neoformans also had significantly increased OD630 readings (Fig. 3) and more reproducible MIC results with YNB when compared with RPMI (Table 1), and with both 80% and 50% inhibition-cutoff MIC analysis remaining constant in YNB (Appendix Table 5). Meanwhile, the MIC analysis using 80% or 50% inhibition-cutoff varied approximately two to three fold in RPMI, with both C. neoformans and C. albicans, due to a more gradual dose response curve in RPMI, compared to more steeper dose response in YNB. However, 80% inhibition-cutoff MIC values across all media types and for the majority of tested antifungals were within the ranges currently presented in the literature. Based on these observations, we selected YNB media as the optimum media for both C. albicans and C. neoformans.

Endpoint readout

The addition of resazurin to C. neoformans plates before reading was included to aid the accuracy of the calculated optical density separation between positive and negative controls. Although C. neoformans has a significantly higher OD when grown in YNB compared to RPMI, the OD630 measurement at the 36 h time point was too low to provide a highly significant separation between positive and negative controls (Z’-factors > 0.5). This is especially important for primary screening at single compound concentrations, which relies on good Z’-factors to select actives for further dose response confirmation. To maintain the 36 h incubation time chosen for its advantages in limiting evaporative loss and edge effect, resazurin was added to the 384-well plates and growth inhibition measured by calculating the difference in absorbance between 570 and 600 nm. The addition of resazurin was done by bulk dispensers or liquid handling robots, with reading the plates after a short incubation time. This adds only little resources and time to the high-throughput screening workflow for C. neoformans while simultaneously improving the quality control of each screen.

In summary, this study concludes that YNB media, incubated at 35 °C for 36 h, in 384 well-NBS plates are the optimal conditions to run high throughput antifungal screening for non-fermentative yeast like C. albicans and C. neoformans, using either OD630 or OD570 − 600 with the addition of resazurin. Using these validated conditions we have been able to test over 300,000 compounds against these two yeast species, while also testing selected compounds against a range of different Candida and Cryptococcus species and clinical isolates with similar assay performances.

While the assay conditions of using YNB media and NBS plates could be applied to other yeast or filamentous fungi, the incubation time may need to be optimised to provide an absorbance readout suitable for high throughput screening, consistent across a 384-well plate format and with statistically significant separation between growth and no growth.

Methods

Strains and antifungals

Strains tested were purchased from the ATCC collection, Candida albicans (Robin) ATCC® 90028, Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (H99) ATCC® 208821. The species were confirmed using the VITEK 2 Compact system and YST identification card. The strains C. albicans and C. neoformans were cultured for 24 and 48 h, respectively, from a fresh glycerol stock onto YPD agar at 35 °C. The strains were then maintained on YPD agar and kept at 4 °C before being used for inoculum preparation for the assays.

Fluconazole (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. 8929), amphotericin B (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. A4888 as powder; Sigma Aldrich Cat No. A2942 as solution in deionized water), 5-fluorocytosine (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. F7129), posaconazole (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. 32103), voriconazole (Cayman Chemical Cat No. 15633), ketoconazole (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. K1003), itraconazole (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. I6657), caspofungin diacetate (Sigma Aldrich No. SML0425), anidulafungin (Carbosynth Cat No. FA16270) and micafungin sodium (Carbonsynth Cat No. FM34148) were purchased from the indicated suppliers. All antifungals were prepared fresh, at 1.28 mg/mL in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from powder stocks. The exception was amphotericin B, in which both the powder form and solution stock of 250 µg/mL were included.

Growth curve assay

Colonies from each culture were re-suspended in 5 mL of sterile water and adjusted to a density of OD = 0.3–0.4 at 530nm (OD530) wavelength, resulting in a yeast stock suspension of 107 cells per mL. These stock suspensions were diluted to the final concentration of 2.5 × 103 CFU/mL in fresh YNB broth (Becton Dickinson Cat No. 233520) supplemented with 2% glucose, or RPMI1640 culture medium (Sigma Cat No. R6504-10 × 1 L) with the addition of 0.165 mol/L MOPS buffer.The RPMI-1640 media was adjusted to a pH of 7, with the addition of 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide, according to CLSI guidelines.

48 µL of the stock suspensions were dispensed, using an automated 16 channel pipette, into each well of the compound containing NBS 384-well plates (Corning Cat No. 3640) and PS 384-well plates (CorningCat No. 3680) in duplicate (n = 2). Fresh media was used as a negative control in the last column. Plates were covered and incubated at 30 °C and 35 °C.

Growth of C. albicans and C. neoformans was determined measuring absorbance at OD630, at 0, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h time points, measured using a Biotek Synergy HTX plate reader. Growth curves were generated using an average of the OD630 values across all corresponding growth wells on each plates (n = 176 wells on 384-well plates with two media conditions and two columns of media only controls). Upon inoculation of the 384-well growth curve plates, a 20 µL sample from each yeast stock suspension was taken and streaked out on YPD agar plates to measure a baseline CFU/mL of the 0 h time point. Subsequently, at each following time point, 20 µL of each strain was taken from the 384-well growth plates for all conditions. The C. albicans culture was diluted 1:10000 for time points 18 h, 24 h and 36 h, and 1:100000 for time points 48 h and 72 h. The C. neoformans culture was diluted 1:1000 for all time points 18 h to 72 h. The samples were struck out on YPD agar and incubated at 35 °C, and after 36 h the colonies were counted to determine the CFU/mL for each condition.

High throughput antifungal screening

Based on the results of the growth curve and subsequent literature search, only specific time points were chosen for each strain to compare MIC results and validate an optimal high throughput screening method for both C. albicans and C. neoformans.

For C. albicans, we chose to compare microbroth dilution using YNB media incubated at 35 °C for 36 h in 384 well plates versus using RPMI-1640 incubated at 35 °C for 48 h, as specified in the CLSI guidelines. For C. neoformans, we chose to compare microbroth dilution using YNB media incubated at 35 °C for 36 h in 384 well plates versus using RPMI-1640 incubated at 35 °C for 72 h, as specified in the CLSI guidelines. Fungal strains and subsequent fungi suspension were prepared in the same manner as the growth curve.

The antifungal standards were added to a 384-well deep well polypropylene V-bottom plate (PerkinElmer Cat No. 6008690), in duplicate, at 10 times the final test concentration. The compounds were then serially diluted two-fold in 20% DMSO, 16 times down the wells of the plate. The Biomek liquid handling robot was used to stamp 5 µL from each well of the 384 well deep well polypropylene V-bottom plate, containing the antifungal standards, into NBS 384 well plates (Corning Cat No.3640) and PS 384-well plates (Corning Cat No. 3680). Then, 45 µL of the fungi suspension in each media was added to the compound-containing 384 well plates, giving a final cell concentration of 2.5 × 103 CFU/mL and a final compound concentration range from 16 µg/mL to 0.00049 µg/mL. All plates were covered with lids and incubated under the described conditions, without shaking.

All tested antifungals had a final DMSO concentration of 2% or lower. For all plates, a DMSO control was added to ensure inhibition was not caused by DMSO concentration. All plates included a positive and negative growth control column in order to calculate inhibition percentage using absorbance.

Growth inhibition of C. albicans was determined by measuring absorbance at OD630, while the growth inhibition of C. neoformans was determined measuring the difference in absorbance OD570 − 600, after the addition of resazurin (0.001% final concentration) and a 5 min short incubation time. All absorbance values were obtained using a Biotek Synergy HTX plate reader. In both cases, the percentage of growth inhibition was calculated for each well, using the negative growth control (media only) and positive growth control (fungi without inhibitors) on the same plate. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration at which growth was fully inhibited, defined by an inhibition ≥ 80% and ≥ 50%.

Data availability

All relevant data are available in the Supplementary Material or from the corresponding author upon request to the following email: j.zuegg@uq.edu.au.

References

World Health Organization. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens list to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action (Geneva, 2022).

Erdogan, A. & Rao, S. S. Small intestinal fungal overgrowth. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 17, 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-015-0436-2 (2015).

Nobile, C. J. & Johnson, A. D. Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330 (2015).

Anderson, M. Z. & Bennett, R. J. Budding off: bringing functional genomics to Candida albicans. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 15, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/bfgp/elv035 (2016).

Naglik, J. R. et al. Differential expression of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase B genes in humans correlates with active oral and vaginal infections. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1086/376536 (2003).

Pappas, P. G. et al. Clinical practice Guideline for the management of Candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Diseases: Official Publication Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 62, e1–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ933 (2016).

Spampinato, C. & Leonardi, D. Candida infections, causes, targets, and resistance mechanisms: traditional and alternative antifungal agents. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013 (204237). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/204237 (2013).

Gibson, J. F. & Johnston, S. A. Immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans and C. Gattii during cryptococcosis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 78, 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2014.11.006 (2015).

Rohatgi, S. & Pirofski, L. A. Host immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans. Future Microbiol. 10, 565–581. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.14.132 (2015).

Kwon-Chung, K. J. et al. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 4, a019760. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a019760 (2014).

Rajasingham, R. et al. The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: A modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1748–1755. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00499-6 (2022).

Rajasingham, R. et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: An updated analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 873–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30243-8 (2017).

Heung, L. J. Innate Immune responses to Cryptococcus. J. Fungi (Basel). 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030035 (2017).

Shapiro, R. S., Robbins, N. & Cowen, L. E. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 213–267. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00045-10 (2011).

Zaragoza, O. et al. Process analysis of variables for standardization of antifungal susceptibility testing of nonfermentative yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 1563–1570. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01631-10 (2011).

Rex, J. H. et al. M27 A3 Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard—Third Edition (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2008).

Balouiri, M., Sadiki, M. & Ibnsouda, S. K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 6, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005 (2016).

Chen, J., Wan, Z. & Li, R. Modified colorimetric assay for susceptibility testing of azole antifungal drugs against Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 1790–1793 (2004).

Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L., Cuenca-Estrella, M., Diaz-Guerra, T. M. & Mellado, E. Standardization of antifungal susceptibility variables for a semiautomated methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2513–2517. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.7.2513-2517.2001 (2001).

Nadeem, S. G., Shafiq, A., Hakim, S. T., Anjum, Y. & Kazm, S. U. Effect of Growth Media, pH and temperature on yeast to Hyphal Transition in Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol.3, 185–192 (2013).

Upadhya, R., Lam, W. C., Hole, C. R., Vasselli, J. G. & Lodge, J. K. Cell wall composition in Cryptococcus neoformans is media dependent and alters host response, inducing protective immunity. Front. Fungal Biol. 4https://doi.org/10.3389/ffunb.2023.1183291 (2023).

Kümmel, A. et al. Integration of multiple readouts into the z’ factor for assay quality assessment. J. Biomol. Screen. 15, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087057109351311 (2010).

Kavanagh, A., Ramu, S., Gong, Y., Cooper, M. A. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. Effects of Microplate Type and Broth Additives on Microdilution MIC susceptibility assays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01760-18 (2019).

CLSI. Performance standards for Antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 1st ed. CLSI Supplement M60. (2017).

Hoeprich, P. D. & Merry, J. M. Influence of culture medium on susceptibility testing with BAY n 7133 and ketoconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 24, 269–271. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.24.2.269-271.1986 (1986).

Pfaller, M. A. et al. Collaborative investigation of variables in susceptibility testing of yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34, 1648–1654. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.34.9.1648 (1990).

Billmyre, R. B., Clancey, A., Li, S., Doering, L. X., Heitman, J. & T. L. & 5-fluorocytosine resistance is associated with hypermutation and alterations in capsule biosynthesis in Cryptococcus. Nat. Commun. 11, 127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13890-z (2020).

Nyilasi, I. et al. In vitro synergistic interactions of the effects of various statins and azoles against some clinically important fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 307, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01972.x (2010).

Mallie, M. et al. In vitro susceptibility testing of Candida and Aspergillus spp. to voriconazole and other antifungal agents using Etest: results of a French multicentre study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 25, 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.11.010 (2005).

Wiederhold, N. P., Najvar, L. K., Bocanegra, R. A., Kirkpatrick, W. R. & Patterson, T. F. Caspofungin dose escalation for invasive candidiasis due to resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 3254–3260. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01750-10 (2011).

Nussbaumer-Proll, A., Matzneller, P., Eberl, S. & Zeitlinger, M. Pulmonary surfactant impacts in vitro activity of selected antifungal drugs against Candida krusei and Candida albicans. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-024-04799-7 (2024).

Keerativasee, S. et al. Heteroresistance to fluconazole among isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans in Northern Thailand. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 7, 4096–4102. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2013.5958 (2013).

Gast, C. E., Basso, L. R. Jr., Bruzual, I. & Wong, B. Azole resistance in Cryptococcus gattii from the Pacific Northwest: investigation of the role of ERG11. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5478–5485. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02287-12 (2013).

Lu, R. Y. et al. New triazole NT-a9 has potent antifungal efficacy against Cryptococcus neoformans In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01628-19

Ding, H. et al. BG40018: a promising drug candidate for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 10, 14401–14407 (2017).

Pianalto, K. M., Billmyre, R. B., Telzrow, C. L. & Alspaugh, J. A. Roles for stress response and cell Wall Biosynthesis pathways in Caspofungin Tolerance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics. 213, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.119.302290 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Spiro[benzoxazine-piperidin]-one derivatives as chitin synthase inhibitors and antifungal agents: design, synthesis and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 243, 114723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114723 (2022).

Li, M., Liao, Y., Chen, M., Pan, W. & Weng, L. Antifungal susceptibilities of Cryptococcus species complex isolates from AIDS and non-AIDS patients in Southeast China. Braz J. Infect. Dis. 16, 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1413-8670(12)70301-x (2012).

Blaskovich, M. A., Zuegg, J., Elliott, A. G. & Cooper, M. A. Helping chemists Discover New Antibiotics. ACS Infect. Dis. 1, 285–287. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00044 (2015).

Zuegg, J., Hansford, K. A., Elliott, A. G., Cooper, M. A. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. How to stimulate and facilitate early stage Antibiotic Discovery. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1302–1304. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00163 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Studies were conducted by the Community for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery, funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) and The University of Queensland (Australia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.E., M.A.T.B., J.F. and J.Z. conceived the study. A.K., G.L., M.A. and H.F. performed the experiments. H.F., A.K., G.L. and J.Z. analysed the resultant data. A.G.E. and J.Z. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Floyd, H.E.E., Kavanagh, A.M., Lowe, G.J. et al. Standardisation of high throughput microdilution antifungal susceptibility testing for Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. Sci Rep 14, 23407 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74068-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74068-2