Abstract

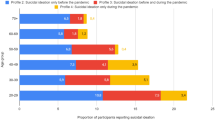

Despite the significant impact of the COVID–19 pandemic on various factors related to adolescent mental health problems such as stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, research on this topic has been insufficient to date. This study is based on the Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web–based Survey from 2006 to 2022. We analyzed the mental health problems of adolescents based on questionnaires with medical interviews, within five income groups and compared them with several risk factors. A total of 1,138,804 participants were included in this study, with a mean age (SD) of 15.01 (0.75) years. Of these, 587,256 were male (51.57%). In 2022, the recent period from the study, the weighted prevalence of stress in highest income group was 40.07% (95% CI, 38.67–41.48), sadness was 28.15% (26.82–29.48), suicidal ideation was 13.92% (12.87–14.97), and suicide attempts was 3.42% (2.90–3.93) while the weighted prevalence of stress in lowest income group was 62.77% (59.42–66.13), sadness was 46.83% (43.32–50.34), suicidal ideation was 31.70% (28.44–34.96), and suicide attempts was 10.45% (8.46–12.45). Lower income groups showed a higher proportion with several risk factors. Overall proportion had decreased until the onset of the pandemic. However, a significant increase has been found during the COVID–19 pandemic. Our study showed an association between household income level and the prevalence of mental illness in adolescents. Furthermore, the COVID–19 pandemic has exacerbated mental illness among adolescents from low household income level, underscoring the necessity for heightened public attention and measures targeted at this demographic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, South Korea has been identified as having the highest rates of adolescent suicide within the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, leading to a significant surge in interest regarding mental health problems among adolescents1. Cultural shift due to exposure to diverse social media, the COVID–19 pandemic, and rising individualism have drawn public attention to mental health problems of adolescents2. Given this perspective, deeper investigations are needed to identify the factors negatively affecting mental health of adolescents. Most studies have primarily focused on adolescents themselves by investigating academic stress or their own mental problems, but there is a need for deeper investigations into socioeconomic factors1,3,4,5. Therefore, we aimed to focus on household income inequality, an essential factor that impacts adolescents to manage their own lives3.

Since the onset of the COVID–19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns, individuals have experienced increased stress and anxiety due to fears of infection and disruptions to daily routines6. Additionally, many have faced social isolation, loneliness, and reduced access to therapeutic services, leading to declines in both physical and mental health7. These negative effects have been especially pronounced among adolescents, who have shown a significant rise in negative mental health indicators8,9.

This shift highlights the necessity to examine the influence of external factors, especially household income level, on the psychological well-being of adolescents during these unprecedented times10. Understanding the association between these factors and adolescent mental health and how this relationship has changed since the pandemic is of paramount importance. Identifying these correlations is crucial for creating more equitable support systems that address the unique challenges faced by vulnerable populations during crises like the COVID–19 pandemic4,5,11,12.

Adolescence represents a critical period for personal development, marked by the formation of distinct personalities13. The mental health status during this formative period not only shapes an individual’s core values but also has a lasting impact on their life trajectory. Consequently, ensuring the maintenance of adolescent mental well-being throughout these crucial years is imperative for fostering a healthy transition into adulthood14.

The process of identity formation during adolescence is significantly influenced by interactions with the surrounding environment such as family and peers15. However, due to global social distancing policies, including school closures and home-based education during the COVID–19 pandemic, as seen in South Korea, social interactions among adolescents have been significantly reduced, leading to a negative impact on their mental health16,17. This necessitates a comprehensive view of surrounding circumstances in research. Consequently, our study aimed to discover how household income level can influence the mental health of adolescents in South Korea before and during the COVID–19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This study is based on the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS). This web-based survey was annually conducted by Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency and reviewed by the Korean Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health and Welfare18. Total of 1,138,804 youth enrolled in middle and high schools (aged 12 to 18) participated in the survey from 2006 to 2022. All of the students voluntarily participated in the survey (mean response rate, 95%).19 The sampling methodology was executed in a structured three-phase process. First, it delineated the population based on geographical and educational parameters. Second, methods of proportional allocation were employed to distribute the samples. The final step employed stratified cluster sampling through the utilization of schools and classrooms as the primary and secondary sampling units, respectively. This approach significantly reduced the potential for sampling discrepancies. Furthermore, incorporating weighting adjustments facilitated a comprehensive representation of the Korean adolescent demographics.

KYRBS data were anonymous, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency (2014-06EXP-02-P-A) and by the local law of the Population Health Promotion Act 19 (117058) from the Korean government. All the participants (or their parents or legal guardians in the case of children under 16) provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Covariates

Household income level was classified as five levels by categorizing the subjective perception of the survey participants, as captured by the question, ‘Please indicate your household’s socioeconomic position’. Other variables included grade (7–9th [middle school] and 10–12th [high school]), sex, residential area (rural and urban), recent alcohol consumption (yes and no), smoking status (yes and no), parental educational attainment (high school diploma or less, bachelor’s degree or higher), school performance (high, middle, and low). Following regions are included in rural (Chungbuk, Chungnam, Gangwon, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, and Jeju) and others are included in urban (Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, Gwangju, Gyeonggi, Incheon, Seoul, Sejong, and Ulsan)20. Recent alcohol intake was categorized as consuming alcohol at least once in the past month. Concurrently, the definition of smoking status encompassed individuals who had smoked any form of cigarette product at least once over the past month21. Additionally, the highest educational attainment of the parents was identified as the highest level of education achieved by either parent.

End points

We investigated how adolescents’ mental health indicators have changed and assessed whether the COVID–19 pandemic has had an impact on these trends. Since the first confirmed case of COVID–19 in South Korea was reported in January 2020, we divided the entire timeline into eight periods. The pre-pandemic era was divided into five periods: period 1 (2006–2008), period 2 (2009–2011), period 3 (2012–2014), period 4 (2015–2017), and period 5 (2018–2019).

In 2020, the country experienced its first major outbreak, leading to strict social distancing measures, including school closures and remote learning22,23. In 2021, despite vaccination efforts, South Korea faced larger waves of infections and many preventive measures remained while some restrictions were eased. In 2022, with the emergence of the Omicron variant, South Korea experienced its highest-ever COVID–19 prevalence rate. Despite this, the mortality rate was 0.13%, the lowest among the 30 countries with the highest case counts24. However, South Korea also transitioned to a “living with COVID–19” strategy, gradually lifting most restrictions. Thus, the pandemic era was also divided into three periods: period 6 (2020), period 7 (2021), and period 8 (2022)21.

The main purpose of our study is to investigate perceived stress level, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in relation to the household income level1,9. To evaluate stress levels, participants were asked to respond to the following question: “How much stress do you typically experience?”. Responses were scored from 1 to 5, and we recategorized scores as low, middle, and high. In the case of sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, respondents were categorized into two groups: yes or no. To assess this, questions were asked respectively: “Have you experienced sadness or despair in the past 12 months that was severe enough to interrupt your daily activities for a continuous period of two weeks?“, “Have you seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months?”, and “Have you attempted suicide in the past 12 months?”2,17,19,25. Household income level is divided into five categories: high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, low. Furthermore, we initially compared the trends of these indicators based on household income level and conducted more detailed examinations based on sex, grade, residential area, recent alcohol consumption, smoking status, parents’ highest educational level, and school performance before and during the COVID–19 pandemic.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the KYRBS data to investigate the national trends in stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts during the past 17 years. All missing data in the ‘age’ covariate were imputed using the standardized mean value of the same year. Regression analysis was used to check the importance of changes over time and patterns. The findings were shared as weighted odds ratios (wORs), or as weighted β-coefficients with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Binary logistic regression and beta difference (βdiff) were employed to compare 2019 to 2020, 2020 to 2021, and 2021 to 202220. Moreover, the βdiff was calculated to evaluate the change in prevalence of depression and suicide attempts before and during the pandemic. We compared the shift in risk factors in the years following the onset of the COVID–19 pandemic (2019–2022) using Fisher’s exact test for types of data that fit into categories. We described the comparison among the household income levels to determine whether the difference was statistically significant, utilizing the odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval26. For all our data analysis, we used SAS software (version 9.4; Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We considered results statistically significant if the two-sided p-value < 0.05.27

Results

Between 2006 and 2022, the KYRBS included a total of 1,138,804 adolescents, comprising 587,256 males (51.57%) and 551,548 females (48.43%). The participants had a mean age [SD] of 15.01 [1.75] years. Among them, 583,626 (51.25%) were middle school students, and 555,178 (48.75%) were high school students. The crude and weighted baseline characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table1 and Table S1.

The overall and weighted prevalence of perceived stress levels, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt is presented in Table1, Table S2, and Table S3. In the most recent survey conducted in 2022, the prevalence of stress levels among participants from high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, and low-income groups were 40.07% (95% CI, 38.67 to 41.48), 38.82% (37.91 to 39.73), 40.41% (39.61 to 41.21), 52.10% (50.47 to 53.73), and 62.77% (59.42 to 66.13), respectively. Similar patterns were observed for sadness [28.15% (26.82 to 29.48), 27.13% (26.32 to 27.94), 27.49% (26.80 to 28.18), 37.64% (36.07 to 39.20), 46.83% (43.32 to 50.34)], suicidal ideation [13.92% (12.87 to 14.97), 12.58% (11.94 to 13.22), 13.27% (12.76 to 13.78), 22.25% (20.87 to 23.64), 31.70% (28.44 to 34.96)], and suicide attempt [3.42% (2.90 to 3.93), 2.14% (1.87 to 2.41), 2.14% (1.87 to 2.41), 3.79% (3.18 to 4.41), 10.45% (8.46 to 12.45)]. These results suggest that adolescents from lower-income households are more likely to experience elevated stress, sadness, and suicidal behavior. However, uniquely in the case of suicide attempts, the highest income group showed a higher value in comparison with the middle and middle-high income groups (Table 2).

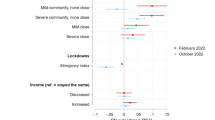

Not just in 2022, but throughout various periods, a consistent relationship was observed between household income levels and mental health indicators. Furthermore, all four mental health indicators experienced a decline prior to the COVID–19 pandemic, followed by a notable increase during the pandemic, illustrating a U-shaped curve as depicted in Fig. 1. In the period of the pandemic, there was an escalation in perceived stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt when compared to the year before. As a reference, the middle income group shows an increasing pattern among four indicators: stress (wOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.17), sadness (1.07; 1.02 to 1.13), suicidal ideation (1.20; 1.02 to 1.13), and suicide attempt (1.10; 0.95 to 1.27) when comparing 2021 with 2020, and similarly, stress (1.20; 1.14 to 1.26), sadness (1.10; 1.05–1.16), suicidal ideation (1.13; 1.06 to 1.21), and suicide attempt (1.22; 1.06 to 1.40) when comparing 2022 with 2021 (Table3 and Table S4).

From 2006 to 2022, significant risk factors for mental health indicators included female sex, high school enrollment, urban residency, alcohol consumption, smoking, higher educational levels of parents, and superior academic performance of students (Table S5). Especially, female sex, alcohol consumption, and smoking status represents tremendous effect to the indicators. Within the middle income group, as a reference point, female sex participants have overall odds ratios (OR) of 1.68 (1.60 to 1.75), 1.63 (1.56 to 1.71), 1.65 (1.60 to 1.69), 1.99(1.71 to 2.32) for stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, respectively, compared to male sex participants. Additionally, for drinking, the OR values are 1.40 (1.31 to 1.50), 1.98 (1.85 to 2.12), 1.91 (1.86 to 1.97), 3.05 (2.56 to 3.63). Similarly, for smoking participants, the OR values are 1.56 (1.37 to 1.77) for stress, 2.50 (2.21 to 2.83) for sadness, 2.08 (2.00 to 2.17) for suicidal ideation, and 5.06 (3.98 to 6.45) for suicide attempts.

Discussion

Key findings

This study is the first long-term follow-up over 17 years to examine the relationship between household income level and mental health among adolescents, as well as their trends. Our findings showed that lower household income levels are associated with mental health indicators such as stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among Korean adolescents. Furthermore, our study indicated that the COVID–19 pandemic has significantly altered the trend in adolescent mental well-being. While there was a decreasing pattern of negative mental health indicators in the pre-pandemic era, there was a surge and a shift to an increasing pattern during the pandemic. This underscores the substantial impact of the COVID–19 pandemic on adolescent mental well-being, emphasizing the need to address not only physical symptoms like respiratory issues but also the mental health challenges faced by adolescents. In addition, we identified the most significant risk factors for negative mental health as being female, alcohol consumption, and smoking status.

Plausible mechanism

We found that students from lower-income households tended to experience higher levels of stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. This could stem from feelings of relative deprivation compared to their peers and the recent social trend that places high importance on wealth28. Adolescents from lower-income households may feel disconnected from their higher-income peers, which can lead to low self-esteem and psychologically depressive thoughts and behaviors.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues by highlighting and intensifying existing inequalities. During lockdown periods, lower-income students were more likely to experience cramped living conditions, limited privacy, and difficulties accessing online education, potentially intensifying feelings of stress and isolation29. Additionally, lower-income families were more likely to experience job losses or reduced work hours during the pandemic, further increasing financial stress and its impact on adolescent mental health30.

In addition, parental psychological distress, rather than socioeconomic status itself, could contribute to these outcomes31. Parental care is crucial for the development of adolescents’ identity, and poor parental care can lead to psychological instability in their children. In collectivistic cultures like Korea, family plays a significant role in interpersonal relationships, and poor family function is closely linked to poor mental health in children32. This phenomenon can result in adolescents feeling isolated, with fewer peers around them33. School factors also play a role, as adolescents’ self-esteem related to school social capital has a similar impact on their mental health as parental factors34. Another potential mechanism is the increased academic pressure in lower-income families, where adolescents might feel a greater need to succeed academically to improve their future prospects35.

Additionally, female sex, alcohol consumption, and smoking status are established risk factors for poor mental health in previous studies. This trend is particularly pronounced among adolescents from low-income backgrounds36,37,38. These adolescents may engage in these risky behaviors as coping mechanisms to deal with the heightened stress and psychological burden they face, which further exacerbates their mental health issues39. The interplay between these factors creates a vicious cycle that is difficult to break, underscoring the need for targeted interventions that address both the socioeconomic and behavioral aspects of adolescent mental health.

These combined factors contribute to the negative mental health outcomes observed in adolescents from lower-income households.

Comparison with previous studies

Several studies have reported the association between household income and adolescents’ mental health, including research in Kenya (n = 2,195), Norway (n = 1,354,393), Canada (n = 29,722), and Germany (n = 2,111)10,40-42. While these studies indicated an association between lower household income levels and increased instances of mental illness among adolescents, they were limited by their small sample sizes and the broad range of participant ages, which included both children and adolescents. In contrast, our investigation is distinguished by its large population-based design, specifically focusing on the age group of 12 to 18 years. Furthermore, our research extends over 17 years, providing insights into the long-term trends and patterns concerning the mental well-being of adolescents. Additionally, we divided income into five groups, which provides a detailed understanding of the impact of income inequality on adolescents’ mental health in South Korea. This approach allows the government or society to implement political interventions and support programs tailored to the specific needs of each income group. By considering both the COVID–19 pandemic and income levels, our study offers a comprehensive understanding of how external factors like the pandemic differently affect each income group. This underscores the necessity of a comprehensive understanding when examining the impact of the pandemic on changes in mental health indicators.

Policy implications

Several previous studies have mainly focused on predicting and preventing suicidal behavior in adolescents and identifying related factors43. However, our study emphasizes that perceived stress levels and sadness are also crucial indicators of adolescents’ mental health, as they can lead to suicidal behavior44. Adolescents are vulnerable and can be influenced by various factors, so it is essential for governments and schools to focus on these negative mental health indicators45. Especially, we discovered female sex, alcohol, and smoking are significant risk factors for the negative mental health indicators. Therefore, find the reason why lower income female students are fragile to mental illness and solution for this. Also, school- or society-based substances abuse prevention programs, like alcohol and tobacco, needed to be prepared delicately for the risky teenagers46.

Moreover, numerous efforts aimed at improving adolescents’ mental health have led to a reduction in the overall incidence of mental health issues among this group47,48. However, the advent of the pandemic has precipitated a significant increase in these mental health challenges2,17. This issue demands urgent and serious discussion and resolution. Addressing the mental health of adolescents is critical, necessitating a collaborative effort from both governments and educational institutions to support students afflicted with mental health conditions. Early identification of mental health issues in each student and the provision of counseling services are essential steps49. Furthermore, encouraging physical activity and in-person social interactions among students, away from the digital confines of smartphones and SNS, is crucial50. In addition, there’s a need to promote the cultivation of social connections that were severed during the lockdowns imposed by the COVID–19 pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between household income and adolescents’ mental health indicators using a South Korean database. Moreover, our research is distinguished by its long-term and large population-based approach, encompassing data from multiple countries. This database enabled us to identify trends both before and during the COVID–19 pandemic. Consequently, we were able to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between income and mental health, as well as how these trends were affected by the pandemic. Additionally, we identified several risk factors, including female sex, alcohol consumption, and smoking status, which further worsened the relationship between income and mental health.

However, our study also has several limitations. First, the KYRBS is conducted among school students, which introduces a bias by excluding non-school students who are homeschooled or have dropped out. Second, the data represents subjective responses rather than objective metrics, which is a limitation inherent to survey-based cohort studies. Adolescents may lack awareness of their household income, potentially introducing biases into their responses. In addition, due to the sensitivity surrounding mental health issues in Korean society, participants might have felt pressured to provide socially acceptable answers, potentially underreporting their symptoms, even though the survey was anonymous. This pressure, combined with the potential reluctance to discuss sensitive topics, could also exacerbate non-response bias, as certain participants might avoid or skip questions they find uncomfortable. Third, the KYRBS dataset utilized does not include a temporal component, preventing us from analyzing the causal relationship between depression and other variables. Finally, since this study is based entirely on pre-existing survey data with predefined questions, it is challenging to explore the specific reasons and mechanisms by which household income levels affect adolescents’ mental health.

Even though we have various limitations, this study still has advantages.

Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate how household income levels affect adolescents’ mental health problems using a long-term, large nationwide survey-based cohort study. The findings indicate the potential association, suggesting that lower-income are more vulnerable to stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among Korean adolescents. Despite that various policies temporarily reduced mental health problems among adolescents, this trend surged with the onset of the COVID–19 pandemic. This is based on evidence that lockdown policies have impacted various aspects of the lives of lower-income adolescents, such as limited access to online education, reduced privacy, and increased feelings of isolation compared to their higher-income peers. As this study is based on survey data to identify associations, future research should investigate the mechanisms by which income influences negative mental health indicators. Furthermore, given that the mental health indicators assessed are related to other psychiatric conditions such as depression, this study provides crucial baseline data for developing policies aimed at the prevention and support of adolescents experiencing mental health challenges.

Data availability

The data are available on reasonable request. Study protocol, statistical code: available from DKY (email: yonkkang@gmail.com). Data set: available from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency through a data use agreement.

Change history

18 July 2025

This article has been updated to amend the license information.

References

Kwak, C. W. & Ickovics, J. R. Adolescent suicide in South Korea: risk factors and proposed multi-dimensional solution. Asian J. Psychiatr. 43, 150–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.05.027 (2019).

Kang, J. et al. National trends in depression and suicide attempts and COVID-19 pandemic-related factors, 1998–2021: a nationwide study in South Korea. Asian J. Psychiatr. 88, 103727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103727 (2023).

Quon, E. C. & McGrath, J. J. Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 33, 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033716 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. Psychosocial alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic and the global burden of anxiety and major depressive disorders in adolescents, 1990–2021: challenges in mental health amid socioeconomic disparities. World J. Pediatr.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-024-00837-8 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Global public concern of childhood and adolescence suicide: a new perspective and new strategies for suicide prevention in the post-pandemic era. World J. Pediatr.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-024-00828-9 (2024).

Pfefferbaum, B. & North, C. S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl. J. Med. 383, 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017 (2020).

Goldschmidt, T. et al. Psychiatric presentations and admissions during the first wave of Covid-19 compared to 2019 in a psychiatric emergency department in Berlin, Germany: a retrospective chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04537-x (2023).

Kose, S. et al. Child and adolescent psychiatric emergency admissions before, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic: an interrupted time series analysis from Turkey. Asian J. Psychiatr. 87, 103698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103698 (2023).

Woo, H. G. et al. National trends in sadness, suicidality, and COVID-19 pandemic-related risk factors among South Korean adolescents from 2005 to 2021. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2314838. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14838 (2023).

Kinge, J. M. et al. Parental income and mental disorders in children and adolescents: prospective register-based study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 1615–1627. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab066 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Short- and long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes in long COVID in South Korea and Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01895-8 (2024).

Cheong, C. et al. National trends in counseling for stress and depression and COVID-19 pandemic-related factors among adults, 2009–2022: a nationwide study in South Korea: stress, depression, and pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 337, 115919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115919 (2024).

Topolewska-Siedzik, E. & Cieciuch, J. Trajectories of identity formation modes and their personality context in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 775–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0824-7 (2018).

Ragnhildstveit, A. et al. Transitions from child and adolescent to adult mental health services for eating disorders: an in-depth systematic review and development of a transition framework. J. Eat. Disord. 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-00984-3 (2024).

Keen, R. et al. Prospective associations of Childhood Housing Insecurity with anxiety and depression symptoms during Childhood and Adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 177, 818–826. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.1733 (2023).

Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 4, 421. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30109-7 (2020).

Lee, J., Ko, Y. H., Chi, S., Lee, M. S. & Yoon, H. K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Korean adolescents’ Mental Health and Lifestyle factors. J. Adolesc. Health. 71, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.05.020 (2022).

Lee, J. H. et al. National trends in sleep sufficiency and sleep time among adolescents, including the late-COVID-19 pandemic, 2009–2022: a nationally representative serial study in South Korea. Asian J. Psychiatr. 93, 103911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2024.103911 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Data Resource Profile: the Korea Youth Risk Behavior web-based Survey (KYRBS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1076–1076e. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw070 (2016).

Oh, J. et al. Hand and oral Hygiene practices of South Korean adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2349249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49249 (2023).

Shin, H. et al. Estimated prevalence and trends in smoking among adolescents in South Korea, 2005–2021: a nationwide serial study. World J. Pediatr. 19, 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00673-8 (2023).

Kim, S., Kim, Y. J., Peck, K. R. & Jung, E. School opening Delay Effect on Transmission dynamics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Korea: based on Mathematical modeling and Simulation Study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 35, e143. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e143 (2020).

Kang, J. et al. South Korea’s responses to stop the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Infect. Control. 48, 1080–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.003 (2020).

Lim, S. & Sohn, M. How to cope with emerging viral diseases: lessons from South Korea’s strategy for COVID-19, and collateral damage to cardiometabolic health. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 30, 100581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100581 (2023).

Lee, J., Jang, H., Kim, J. & Min, S. Development of a suicide index model in general adolescents using the South Korea 2012–2016 national representative survey data. Sci. Rep. 9, 1846. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38886-z (2019).

Park, J. et al. National trends in asthma prevalence in South Korea before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 1998–2021. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 53, 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.14394 (2023).

Choi, J. et al. Sadness, counseling for sadness, and sleep time and COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea: Rapid review and a post-hoc analysis. Life Cycle. 3, e18. https://doi.org/10.54724/lc.2023.e18 (2023).

Lv, M., Zhang, M., Huang, N. & Fu, X. Effects of Materialism on Adolescents’ Prosocial and Aggressive Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Empathy. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100863 (2023).

Masonbrink, A. R. & Hurley, E. Advocating for children during the COVID-19 School closures. Pediatrics. 146https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1440 (2020).

Gassman-Pines, A., Ananat, E. O. & Fitz-Henley, J. 2 COVID-19 and parent-child Psychological Well-being. Pediatrics. 146https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-007294 (2020).

Yang, M., Carson, C., Creswell, C. & Violato, M. Child mental health and income gradient from early childhood to adolescence: evidence from the UK. SSM Popul. Health. 24, 101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101534 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. The relationship of family functioning and suicidal ideation among adolescents: the Mediating Role of Defeat and the moderating role of meaning in life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315895 (2022).

Hjalmarsson, S. & Mood, C. Do poorer youth have fewer friends? The role of household and child economic resources in adolescent school-class friendships. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 57, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.08.013 (2015).

Bai, X. et al. Subjective family socioeconomic status and peer relationships: mediating roles of self-esteem and perceived stress. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 634976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.634976 (2021).

Hosseinkhani, Z., Hassanabadi, H. R., Parsaeian, M., Karimi, M. & Nedjat, S. Academic stress and adolescents Mental Health: a Multilevel Structural equation modeling (MSEM) Study in Northwest of Iran. J. Res. Health Sci. 20, e00496. https://doi.org/10.34172/jrhs.2020.30 (2020).

Hahad, O. et al. The association of smoking and smoking cessation with prevalent and incident symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 313, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.083 (2022).

Yoon, Y., Eisenstadt, M., Lereya, S. T. & Deighton, J. Gender difference in the change of adolescents’ mental health and subjective wellbeing trajectories. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 32, 1569–1578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01961-4 (2023).

Mäkelä, P., Raitasalo, K. & Wahlbeck, K. Mental health and alcohol use: a cross-sectional study of the Finnish general population. Eur. J. Public. Health. 25, 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku133 (2015).

Li, M. et al. The relationship between harsh parenting and adolescent depression. Sci. Rep. 13, 20647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48138-w (2023).

Pinchoff, J. et al. How has COVID-19-Related income loss and Household Stress Affected Adolescent Mental Health in Kenya? J. Adolesc. Health. 69, 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.023 (2021).

Benny, C. et al. Income inequality and mental health in adolescents during COVID-19, results from COMPASS 2018–2021. PLoS One. 18, e0293195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293195 (2023).

Reiss, F. et al. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS One. 14, e0213700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213700 (2019).

Kim, H. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of suicidal thinking in adolescents by derivation and validation in 3 independent Worldwide cohorts: Algorithm Development and Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e55913. https://doi.org/10.2196/55913 (2024).

Liu, R. T. & Spirito, A. Suicidal behavior and stress generation in adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7, 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618810227 (2019).

Brown, B. et al. Associations between Neighborhood resources and Youth’s response to reward omission in a Task modeling negatively biased environments. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2024.05.011 (2024).

Feinberg, M. E. et al. Long-term effects of adolescent substance Use Prevention on participants, partners, and their children: Resiliency and outcomes 15 years later during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Sci. 23, 1264–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01384-2 (2022).

Gijzen, M. W. M., Rasing, S. P. A., Creemers, D. H. M., Engels, R. & Smit, F. Effectiveness of school-based preventive programs in suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 298, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.062 (2022).

Liu, X. Q. & Wang, X. Adolescent suicide risk factors and the integration of social-emotional skills in school-based prevention programs. World J. Psychiatry. 14, 494–506. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i4.494 (2024).

Lustig, S. et al. The impact of school-based screening on service use in adolescents at risk for mental health problems and risk-behaviour. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 32, 1745–1754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01990-z (2023).

Chao, M., Lei, J., He, R., Jiang, Y. & Yang, H. TikTok use and psychosocial factors among adolescents: comparisons of non-users, moderate users, and addictive users. Psychiatry Res. 325, 115247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115247 (2023).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT; RS-2023-00248157) and the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) support program (IITP-2024-RS-2024-00438239) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Dong Keon Yon had full access to all data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript before submission. Study concept and design: JC, JP, HJ, JH, and DKY; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: JC, JP, HJ, JH, and DKY; drafting of the manuscript: JC, JP, HJ, JH, and DKY; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: JC, JP, HJ, JH, and DKY; study supervision: DKY. DKY supervised the study and served as the guarantor. JC, JP, and HJ contributed equally as first authors. JH, LS, and DKY contributed equally as corresponding authors. LS and DKY is the senior author. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria, and that no one meeting the criteria has been omitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, J., Park, J., Lee, H. et al. National trends in adolescents’ mental health by income level in South Korea, pre– and post–COVID–19, 2006–2022. Sci Rep 14, 25021 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74073-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74073-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Death recollection moderates stress-influenced depression in Thai boarding school students

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

Sex differences in peer victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2025)