Abstract

The aim of this study was to retrospectively determine the effects of applying different treatment methods to the bony access window on the healing outcomes in lateral sinus floor elevation (SFE). Lateral SFE with implant placement was performed in 131 sinuses of 105 patients. The following three treatment methods were applied to the bony access window: application of a collagen barrier (group CB), repositioning the bone fragment (group RW) and untreated (group UT). Radiographic healing in the window area, augmented bone height changes and marginal bone level changes were examined. Mixed logistic and mixed linear models were analyzed. Over 4.3 ± 1.4 years of follow-up, the implant survival rate was 100% in groups CB and UT, and 96.9% in group RW. The treatment applied to the window did not significantly influence the radiographic healing in the window area, augmented bone height changes or marginal bone level changes (p > 0.05). The healed window areas had generally flat morphologies and were fully corticalized. The mean changes in the augmented bone were less than 1.5 mm in all groups. Marginal bone level changes were minimal. In conclusion, Healing outcomes were not different among three different methods to treat the bony access window in lateral SFE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indications for dental implant treatment have expanded widely, and now most treatment plans for missing teeth involve the use of implants1. However, some local tissue conditions require additional augmentation procedures to be performed simultaneously with implant placement or separately for reasons such as to ensure mastication load-bearing capability, mechanical or biological stability, and aesthetics. In the posterior maxilla, reduced bone height is a predominant issue due to maxillary sinus pneumatization2,3. The introduction of sinus floor elevation (SFE) procedures has increased the feasibility of attaining a sufficient amount of bone for supporting an implant4,5.

Different SFE procedures can be chosen according to the residual bone height6. Studies have demonstrated that successful transcrestal SFE is possible when the residual bone height is ≥ 5 mm7,8,9. When the residual bone height is ≤ 4 mm, lateral SFE is recommended for increasing the treatment predictability (for detaching the sinus membrane sufficiently and grafting bone-substitute material properly)10,11. A current drive for minimal invasiveness has further highlighted the usefulness of transcrestal SFE12, but lateral SFE is still performed due to the restricted visibility of and accessibility to the sinus membrane when performing transcrestal SFE.

Several approaches are used to make the bony access window in the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus during lateral SFE13. This bony window allows direct access to the sinus membrane and sinus cavity. After completing the grafting of bone-substitute material in the sinus cavity, it is recommended to cover the bony access window in order to prevent soft-tissue infiltration into and the migration of graft material out of the sinus cavity9,14,15. The role of a barrier over the window in lateral SFE is similar to that in guided bone regeneration. Such a barrier protects the augmented sinus cavity to promote a desirable cell population and space maintenance6,9,14. Furthermore, the maxillary sinus is influenced by respiratory action. For example, air pressure from the nasal cavity transferred to the sinus can push the bone-substitute material, which can be minimized by adding a barrier over the bony window area15. There are two ways to cover the window: The first is using a barrier membrane (predominantly collagen membrane) to cover the access window and neighbouring area, overlapping the window margin by > 2 mm13, The second is to deploy the bone fragment that is detached from the window site when a bony access window is made using a surgical bur or piezoelectric device. This detached fragment can be repositioned at the window site instead of using a barrier membrane16.

However, some authors have questioned the need for a barrier over the access window. A recent preclinical study using a rabbit sinus found no statistically significant differences in new bone formation or total augmented area between groups with and without a barrier membrane17. Similar results have also been found in a few clinical studies. Barone et al. (2013) found similar new bone formation in the groups with and without membrane coverage (30.7% vs. 28.1%) in core biopsy specimens18. Imai et al. (2020) found that the changes in augmentation height and area after 9 months of healing did not differ significantly between groups with and without membrane coverage (0.6 mm vs. 0.8 mm and 10–11% vs. 15–20%, respectively)19.

The available data regarding treatments applied to the access window were mainly derived from comparisons between two groups16,18,20,21 and results obtained in studies involving a single group22,23. Moreover, the samples in these studies have been relatively small. Hence, it remains necessary to elucidate the effects of applying various treatments to the bony access window in larger samples. This information would facilitate the ability to choose the best—or at least an acceptable—option from alternative clinical options in individual cases.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to retrospectively determine the effects of three different approaches for treating the bony access window in lateral SFE.

Results

Lateral SFE was performed in 131 sinuses of 105 patients aged 62.1 ± 11.1 years, comprising 62 males and 43 females, with 266 implants placed simultaneously with lateral SFE. The patients included 77 non-smokers. The follow-up period was 4.3 ± 1.4 years (Table 1).

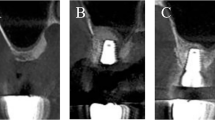

The 131 sinuses comprised 33, 24 and 64 in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively. Sinus membrane perforation was detected in 54 sinuses, but no patients reported abnormal sino-nasal symptoms after the initial healing period. The residual bone height was 2.7 ± 0.9 mm at T0 (2.3 ± 0.8, 3.2 ± 0.8 and 2.8 ± 0.8 mm in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively). Immediately after lateral SFE (T1), the bone height (between the bone crest and the top of the augmented bone) increased to 17.4 ± 2.7 mm (17.2 ± 2.6, 17.8 ± 2.7 and 17.3 ± 2.8 mm in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively), and decreased slightly to 16.4 ± 2.8 mm (16.2 ± 2.7, 17.0 ± 2.7 and 16.3 ± 3.0 mm, respectively) after final prosthesis insertion (T2). At the last follow-up visit (T3), small but continuous decreases in the bone height were measured (15.8 ± 2.7, 16.4 ± 2.9 and 15.9 ± 3.0 mm, respectively) (Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2).

The most common morphology in the bony window area was flat (60.6%, 82.4% and 68.8% in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively), followed by a protruded appearance (33.3%, 17.6% and 28.1% in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively), with a depressed appearance being infrequent (with none in group RW). Unintegrated bone-substitute particles were rarely observed in all groups. No scattering of the particles out of the sinus cavity was observed. Most areas were fully corticalized (90.9%, 85.3% and 73.4% in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively), with only two sites appearing to lack corticalization (one in each of groups CB and UT). The extents of protrusion of the healed window area were 0.4 ± 0.6, 0.4 ± 0.7 and 0.5 ± 0.7 mm in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively (Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2).

Two implants failed in one of the patients (in group RW), which was due to a loss of osseointegration. Each failure occurred prior to final prosthesis insertion. The marginal bone level was stable for the remaining 264 of the 266 implants. The overall change in the marginal bone level was 0.1 ± 0.5 mm: 0.1 ± 0.4 and 0.2 ± 0.6 mm at the mesial and distal aspects, respectively (Table 1).

Mixed logistic models

In the mixed logistic models, sex, smoking and residual bone height at T0 significantly influenced sinus membrane perforation (p < 0.05), with odds ratios of 0.23 (vs. male), 6.84 (vs. non-smoker) and 0.64 (for increasing the bone height by 1.0 mm), respectively (Appendix 1).

The treatment applied to the bony access window did not significantly influence the radiographic healing (both morphology and corticalization) of the bony access window area (p > 0.05) (Appendices 2, 3). However, the morphology was significantly influenced by sex, DM, smoking, implant length and diameter, sinus angle and width, lateral wall thickness, and residual bone height at T0 (p < 0.05).

Mixed linear models

In the mixed linear models, the changes in the height of the augmented bone were not significantly influenced by the treatment applied to the bony access window (p > 0.05). The changes between T1 and T3 were significantly influenced by the lateral wall thickness (with less shrinkage for a thicker wall), while those between T2 and T3 were significantly influenced by the type of bone-substitute material (with more shrinkage for the Osteon 3 than the Osteon 2 material) (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Data are mean ± standard-deviation or n values. CV, cardiovascular diseases; DM, diabetes mellitus; O1, Osteon I; O2, Osteon 2; O3, Osteon 3; T0, before lateral sinus floor elevation (SLE); T1, immediately after lateral SFE/simultaneous implant placement; T2, after final prosthesis insertion; T3, at the last follow-up visit.

The extent of protrusion of the healed window area was not significantly associated with the treatment applied to the bony access window (p > 0.05), but it was significantly influenced by DM and the sinus width (p < 0.05) (Appendix 4).

The marginal bone level change was significantly influenced by DM and the treatment applied to the bony access window (p < 0.05) (Appendix 5). However, the changes were less than 0.5 mm in all cases.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of using three different approaches to treat the bony access window in lateral SFE: barrier membrane, repositioned bone fragment and no coverage. It was demonstrated that (1) the treatment methods applied to the bony access window did not influence the augmented bone height, marginal bone level or implant survival, (2) the radiographic healing in the window area did not differ significantly among the groups, (3) smoking and the residual bone height at baseline significantly influenced sinus membrane perforation, and (4) certain factors significantly affected the marginal bone level but they appeared to be clinically negligible.

The use of a barrier membrane to cover the bony access window has been advocated. Several systematic reviews have demonstrated higher implant survival rates or lower failure rates of implants in an augmented sinus with barrier membrane coverage than in a sinus without such coverage9,14,24,25. The rationale of using a barrier membrane is consistent with the concept of guided bone regeneration. In this context, the bone fragment that is detached from the lateral sinus wall to gain access the sinus cavity can be repositioned. Even though the repositioned fragment does not completely cover the access window (due to the presence of cutting lines along the outline of the window), its presence may reduce soft-tissue ingrowth and act as an osteopromotive substrate16,23. Moreover, utilizing the available bone fragment decreases the treatment cost relative to using a barrier membrane. A few studies that have compared using a barrier membrane and repositioning the bone fragment have found no difference between these two approaches in terms of bone-to-implant contact ratio, intrasinus bone levels, amount of new bone formation or patient discomfort16,26.

Despite the above evidence, some may question the need for using a barrier membrane or repositioned bone fragment to cover the access window. The following factors are important to consider when addressing this question: (1) there is considerable healing sources for maxillary sinus from the surrounding bone walls and even the sinus membrane, and (2) the sinus is shaped like a bowl, which makes it suitable for containing bone-substitute material in a stable manner. It is particularly interesting that some clinical and preclinical studies have found no differences in vital bone formation and the augmented dimensions between sinuses with and without the use of a barrier membrane17,18,19. In line with those previous observations, the present study found no significant differences in the changes in the augmented bone height and implant survival among the three groups. The reductions in bone height were 1.3 ± 2.2 mm (over 4.8 ± 1.4 years), 1.4 ± 1.8 mm (over 3.6 ± 1.2 years) and 1.4 ± 1.6 mm (over 4.4 ± 1.4 years) in groups CB, RW and UT, respectively. Other studies using similar synthetic bone-substitute materials have found comparable changes: 0.27 ± 1.08 and 0.89 ± 1.39 mm at 35 and 72 months, respectively27, 2.24 ± 2.41 mm at 36 months28 and 6.6% at 6 months29.

Only two implants failed in the present study, both in group RW, resulting in the survival rate of implants being 100% in groups CB and UT, and 96.9% in group RW. Due to the low incidence, it was not feasible to statistically analyze the association between implant failure and selected variables in this study (including the treatment applied to the bony access window).

The present study evaluated radiographic healing in the bony access window area using both morphology and corticalization. A flat morphology was most common in each group. However, the incidence of protruded morphology was higher in groups CB and UT than in group RW, without a significant difference between them. Pressure from the sinus membrane post-SFE might have been responsible for this healing outcome. However, the mean extent of the protrusion was less than 1.0 mm in all groups, and such protrusion did not differ significantly among the groups. Different results have been obtained previously15, with bone graft material being displaced out of the sinus by 0.5 ± 0.4 mm with a barrier membrane and 3.8 ± 3.1 mm without a membrane. This discrepancy between the results regarding radiographic healing might be due to the follow-up being considerably longer in the present study (4.3 ± 1.4 years) than in the study of Ohayon et al. (6 months). A longer follow-up is very likely to result in any displaced material being resorbed over time.

In terms of corticalization, the incidence of full corticalization was higher in groups CB and RW than in group UT. Molnár and colleagues (2022) performed re-entry (for implant placement) at 6 months after lateral SFE with the application of a barrier membrane or a repositioned bone fragment to the window16. Those authors observed that the bone-substitute particles were imbedded in the newly formed bone and the repositioned bone fragments were fully integrated in the respective sites. In the present study all implants were placed simultaneously with SFE, and thus direct observations were not possible. On CBCT images, bone-substitute particles-like pieces were rarely observed at the cortical bone level in all groups, indicating favourable integration of the particles with newly formed bone. However, it should be noted that there can be some differences between clinical and radiographic observations due to the resolution of CBCT. The follow-up period and defect characteristics (sufficient bone walls and favorable shape) might have contributed to these observations.

Other factors influencing the radiographic morphology in the healed window area were smoking, sinus angle and width, lateral wall thickness, and residual bone height at T0. A habit that exerts pressure on the sinus membrane and anatomical conditions can influence healing in the bony window area, but such influences appeared not to be associated with implant stability or survival.

It is worth mentioning that some factors were related to sinus membrane perforation, with smoking and residual bone height in particular being identified as risk factors in systematic reviews30,31. It is suspected that the condition of the sinus membrane deteriorates to make it susceptible to perforation and tearing32. An association between a reduced bone height and increased risk of sinus membrane perforation can be explained by a higher tension of the membrane during attempting to detach the sinus membrane to an increased extent33.

In the present study, three bone substitute materials (O1, O2 and O3) were used. All materials were biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP), composed of beta-tricalcium phosphate (beta-TCP) and hydroxyapatite (HA), with different ratios in each material. O1 comprises 70% HA + 30% beta TCP, O2 30% HA + 70% beta TCP, and O3 60% HA + 40% beta TCP. One can argue that those differences may influence the radiographic bone height changes due to different characteristics of components: beta-TCP resorbs fast and replaces with newly formed bone, but HA resorbs slowly and plays a role in maintaining dimensional stability. In preclinical models, heterogeneous findings were noted in terms of new bone formation and dimensional stability depending on the ratio of HA and beta-TCP34,35: significant difference in the former one using the mandible in minipig, but no significant effect in the latter using the sinus in the rabbit. However, it is more probable that the different ratios would not significantly impact sinus augmentation because the sinus cavity is a containing-type defect, which indicates that it is more favorable for new bone formation and dimensional maintenance17. A few clinical studies are available for BCPs with different HA: beta-TCP ratios, and thus, it is hard to conclude whether different HA: beta-TCP ratios lead to a significant difference in sinus augmentation (even though, in the present study, statistically significant shrinkage of the radiographic bone height between T2 and T3 was noted for the Osteon 3 compared to the Osteon 2). In other clinical studies, BCPs yielded 0.89 ± 1.39 mm of height loss at 72 months 27 and 15.7% of volume loss at 6 months36.

The change in marginal bone level was less than 0.5 mm over 4.3 ± 1.4 years of follow-up in this study, which indicates successful integration and functioning of the implants in the augmented sinuses. It is also worth mentioning that regular implant maintenance programs contributed to such favorable marginal bone stability.

There were some limitations in this study. First, the groups were not randomly assigned due to the retrospective design, and so bias might have been present. Second, histological evaluations were not performed. Third, the window size was not exactly the same for each patient, but the size inevitably varied depending on the number of implants to be placed and the local anatomical situation. Fourth, all surgeries were performed by a single experienced surgeon. While this helped to improve the consistency of the outcomes, it might have adversely affected the external validity.

In conclusion, within the limitation of this study, implant survival, radiographic healing in the window area, augmented bone height changes and marginal bone level changes were not different among the three methods of treatment applied to the bony access window in lateral SFE.

Methods

Study design

This study included patients who underwent lateral SFE between January 2016 and December 2020. All patients were treated by the same experienced periodontist (W.-B.P.) in a private clinic. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research and Ethics Committee Hanyang University Hospital (HYUH 2023-04-019). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Institutional Review Board (Hanyang University Hospital) waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The present study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The STROBE guidelines were observed while preparing this manuscript.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

1.

Good general health.

-

2.

Older than 20 years.

-

3.

Presence of an edentulous posterior maxilla with maxillary sinus pneumatization.

-

4.

Residual bone height < 5 mm.

-

5.

Adequate oral hygiene and periodontal condition for implant treatment.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

1.

Systematic disease contraindicating dental surgery, such as uncontrolled metabolic disease, or head/neck radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

-

2.

Local sino-nasal conditions contraindicating SFE.

-

3.

Untreated periodontal diseases.

-

4.

Heavy smoker (> 10 cigarette per day).

A total of 105 patients (131 sinuses) met those criteria.

Study groups

The following study groups were established based on the treatments applied to the bony access window:

-

1.

Group CB (collagen barrier): covering the bony window with a collagen barrier.

-

2.

Group RW (repositioned window): repositioning the bone fragment that was detached from the lateral wall of the sinus.

-

3.

Group UT (untreated): leaving the window to heal without any treatment.

Surgical procedures

All patients were administered 2.0 g of amoxicillin orally 1 h before surgery. Under local anaesthesia using 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine, a mucoperiosteal flap was elevated to expose the lateral surface of the maxillary sinus. A surgical round bur was used to prepare a bony access window. The outline of the bony window was grooved carefully, followed by gentle pushing or hammering using an osteotome to induce greenstick fractures. Subsequently, the bone fragment within the access window was carefully detached from the sinus membrane. The size of the access window varied somewhat between the cases, but generally fell within the following ranges: mesio-distal length of 15–20 mm and apico-coronal height of 6–10 mm. After the bony access window had been prepared, the sinus membrane was carefully elevated from the sinus bone walls using sinus curettes (DASK kit, Dentium, Seoul, Korea). Synthetic bone-substitute material was then grafted (Osteon 1; O1, Osteon 2; O3 or Osteon 3; O3, Genoss, Suwon, Korea). Simultaneous implant placement (Implantium, Dentium) was performed in all cases. The microthreaded portion of the implant helped obtain a sufficient level of primary implant stability, especially in cases of low bone quality and very limited residual bone. Depending on the case, undersized drilling was performed to increase primary stability further. When residual bone height was less than 2 mm, sub-crestal implant placement was avoided.

After bone grafting and implant placement, a cross-linked collagen barrier (Genoss Collagen Membrane, Genoss) was applied to the window and its nearby surrounding area in group CB, with the barrier extending 2–3 mm beyond the window margin. In group RW the detached bone fragment was repositioned, while no other treatment was performed in group UT. In case of bony deficiency (other than the sinus), guided bone regeneration was performed using the same bone substitute material and collagen barrier. The flaps were sutured for submerged healing using non-resorbable suture material (Fig. 3).

In 54 (41.2%) of 131 sinuses, sinus membrane perforation was detected while detaching the bony window and elevating the sinus membrane. The size of the perforation varied roughly between 2 and 4 mm. After elevating the sinus membrane, a Prichard periosteal elevator was inserted under the elevated membrane to hold it up and to protect the perforated area37. In most cases the perforated area was spontaneously covered when folding the membrane during the elevation process. Bone-substitute material was then gently grafted while taking care to minimize the pressure applied to the sinus membrane. No other treatment was applied, such as covering the perforated site with a collagen barrier.

The patients were prescribed antibiotics (amoxicillin 250 mg, Ildong Pharmaceutical Co. Seoul, Korea) and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (Etodol® 200 mg, Yuhan Co. Seoul, Korea) for 7 days (thrice a day). They were instructed to rinse their mouths with 0.12% chlorhexidine solution (Hexamedine, Bukwang Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea). In the case of membrane perforation, the duration of medication was extended to 14 days.

At 4–6 months post-sinus augmentation/implant placement, implant sites were uncovered, and healing abutments were connected. After 1–2 months, final prostheses were delivered. All patients were recommended to visit the dental clinic at least twice per year for an implant maintenance program.

Data collection and measurement

The following data were collected from the patients’ records: age, sex, systemic diseases (diabetes mellitus [DM] or cardiovascular diseases), smoking, implant length and diameter, and bone-substitute material.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans were performed at several time points pre- and post-operatively for each patient. For the CBCT scans, the following time points were chosen for evaluating the bone height (residual bone height plus augmented bone height): before lateral SFE (T0), immediately after lateral SFE (T1), after final prosthesis insertion (T2) and at the last follow-up visit (T3). For performing the measurements, the CBCT images were superimposed using computer software (OnDemand3D, CyberMed, Irvine, CA, USA) to find the best-matched sections. Then, on the same sagittal sections, the height of apico-coronal bone was measured along the long axis of the implant37,38. The changes in augmented bone height were calculated between different time points (Fig. 4).

The lateral wall thickness, the angle between the lateral and medial walls of the sinus, and the width of sinus (3 mm above the bottom of the sinus floor) were also measured at T0. At T3, the radiographic healing in the bony access window area was assessed using the CBCT scans. The healing outcome was classified based on morphology (flat, protruded or depressed) and corticalization (full or partial). Moreover, protrusion or depression of the final surface of the healed window area was measured with respect to the adjacent bone surface (Fig. 4).

Marginal bone level changes between T2 and T3 on the mesial and distal sides of implants were also calculated, and those values were averaged (Fig. 4).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using standard statistical software (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary NC). Data are presented as mean ± standard-deviation or median and interquartile range. The data in the current dataset were analysed at the patient and implant levels, since some patients underwent multiple implant placement.

We applied a mixed binomial logistic model for sinus membrane perforation, a mixed multinomial logistic model for radiographic healing in the window area and mixed linear models for the changes in the augmented bone height and marginal bone level. The independent variables in those models included sex, systemic diseases, smoking, treatments applied to the bony access window, bone-substitute material, age, implant diameter and length, sinus width, sinus angle, lateral wall thickness and residual bone height at T0. A difference was considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Quirynen, M., Herrera, D., Teughels, W. & Sanz, M. Implant therapy: 40 years of experience. Periodontol 2000. 66, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12060 (2014).

Lim, H. C. et al. Factors affecting maxillary sinus pneumatization following posterior maxillary tooth extraction. J. Periodontal Implant Sci.51, 285–295. https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2007220361 (2021).

Sharan, A. & Madjar, D. Maxillary sinus pneumatization following extractions: a radiographic study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 23, 48–56 (2008).

Boyne, P. J. & James, R. A. Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. J. oral Surg.38, 613–616 (1980).

Tatum, H. Maxillary and sinus implant reconstructions. Dental Clin. N. Am.30, 207–229 (1986).

Lundgren, S. et al. Sinus floor elevation procedures to enable implant placement and integration: techniques, biological aspects and clinical outcomes. Periodontol 2000. 73, 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12165 (2017).

Pjetursson, B. E. & Lang, N. P. Sinus floor elevation utilizing the transalveolar approach. Periodontol 2000. 66, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12043 (2014).

Pjetursson, B. E. et al. Maxillary sinus floor elevation using the (transalveolar) osteotome technique with or without grafting material. Part I: Implant survival and patients’ perception. Clin. Oral Implants Res.20, 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01704.x (2009).

Pjetursson, B. E., Tan, W. C., Zwahlen, M. & Lang, N. P. A systematic review of the success of sinus floor elevation and survival of implants inserted in combination with sinus floor elevation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 35, 216–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01272.x (2008).

Gatti, F. et al. Maxillary sinus membrane elevation using a Special Drilling System and hydraulic pressure: a 2-Year prospective cohort study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent.38, 593–599. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.3403 (2018).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Effectiveness of hydraulic pressure-assisted sinus augmentation in a rabbit sinus model: a preclinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 26, 1581–1591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04131-z (2022).

Farina, R., Franzini, C., Trombelli, L. & Simonelli, A. Minimal invasiveness in the transcrestal elevation of the maxillary sinus floor: a systematic review. Periodontol 2000. 91, 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12464 (2023).

Wallace, S. S. et al. Maxillary sinus elevation by lateral window approach: evolution of technology and technique. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract.12, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1532-3382(12)70030-1 (2012).

Duttenhoefer, F. et al. Long-term survival of dental implants placed in the grafted maxillary sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment modalities. PLoS One. 8, e75357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075357 (2013).

Ohayon, L., Taschieri, S., Friedmann, A. & Del Fabbro, M. Bone graft displacement after Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation with or without Covering Barrier membrane: a retrospective computed tomographic image evaluation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 34, 681–691. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.6940 (2019).

Molnár, B. et al. Comparative analysis of lateral maxillary sinus augmentation with a xenogeneic bone substitute material in combination with piezosurgical preparation and bony wall repositioning or rotary instrumentation and membrane coverage: a prospective randomized clinical and histological study. Clin. Oral Investig. 26, 5261–5272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-022-04494-x (2022).

Sim, J. E. et al. Effect of the size of the bony access window and the collagen barrier over the window in sinus floor elevation: a preclinical investigation in a rabbit sinus model. J. Periodontal Implant Sci.52, 325–337. https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2105560278 (2022).

Barone, A. et al. A 6-month histological analysis on maxillary sinus augmentation with and without use of collagen membranes over the osteotomy window: randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res.24, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02340.x (2013).

Imai, H. et al. Tomographic Assessment on the influence of the Use of a Collagen Membrane on dimensional variations to protect the Antrostomy after Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 35, 350–356. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.7843 (2020).

Moon, Y. S. et al. Comparative histomorphometric analysis of maxillary sinus augmentation with absorbable collagen membrane and osteoinductive replaceable bony window in rabbits. Implant Dent.23, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0000000000000031 (2014).

Tawil, G., Barbeck, M., Unger, R., Tawil, P. & Witte, F. Sinus floor elevation using the lateral Approach and Window Repositioning and a xenogeneic bone substitute as a Grafting Material: a histologic, histomorphometric, and Radiographic Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 33, 1089–1096. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.6226 (2018).

Cho, Y. S., Park, H. K. & Park, C. J. Bony window repositioning without using a barrier membrane in the lateral approach for maxillary sinus bone grafts: clinical and radiologic results at 6 months. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 27, 211–217 (2012).

Kim, J. M. et al. Benefit of the replaceable bony window in lateral maxillary sinus augmentation: clinical and histologic study. Implant Dent.23, 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0000000000000070 (2014).

Del Fabbro, M., Wallace, S. S. & Testori, T. Long-term implant survival in the grafted maxillary sinus: a systematic review. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent.33, 773–783. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.1288 (2013).

Wallace, S. S. & Froum, S. J. Effect of maxillary sinus augmentation on the survival of endosseous dental implants. A systematic review. Ann. Periodontol. 8, 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.328 (2003).

Johansson, L. A., Isaksson, S., Bryington, M. & Dahlin, C. Evaluation of bone regeneration after three different lateral sinus elevation procedures using micro-computed tomography of retrieved experimental implants and surrounding bone: a clinical, prospective, and randomized study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 28, 579–586. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.2892 (2013).

Cha, J. K. et al. Maxillary sinus augmentation using biphasic calcium phosphate: dimensional stability results after 3–6 years. J. Periodontal Implant Sci.49, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2019.49.1.47 (2019).

Kim, D. H., Ko, M. J., Lee, J. H. & Jeong, S. N. A radiographic evaluation of graft height changes after maxillary sinus augmentation. J. Periodontal Implant Sci.48, 174–181. https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2018.48.3.174 (2018).

Mordenfeld, A., Lindgren, C. & Hallman, M. Sinus floor augmentation using Straumann(R) BoneCeramic and Bio-oss(R) in a Split Mouth Design and later Placement of implants: a 5-Year report from a longitudinal study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res.18, 926–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12374 (2016).

Krennmair, S. et al. Risk factor analysis affecting sinus membrane perforation during lateral window maxillary sinus elevation surgery. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 35, 789–798. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.7916 (2020).

Wang, X., Ma, S., Lin, L. & Yao, Q. Association between smoking and schneiderian membrane perforation during maxillary sinus floor augmentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res.25, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.13146 (2023).

von Arx, T., Fodich, I., Bornstein, M. M. & Jensen, S. S. Perforation of the sinus membrane during sinus floor elevation: a retrospective study of frequency and possible risk factors. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 29, 718–726. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.3657 (2014).

Schwarz, L. et al. Risk factors of membrane perforation and postoperative complications in sinus floor elevation surgery: review of 407 augmentation procedures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg.73, 1275–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.01.039 (2015).

Jensen, S. S. et al. Evaluation of a novel biphasic calcium phosphate in standardized bone defects: a histologic and histomorphometric study in the mandibles of minipigs. Clin. Oral Implants Res.18, 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01417.x (2007).

Lim, H. C., Zhang, M. L., Lee, J. S., Jung, U. W. & Choi, S. H. Effect of different hydroxyapatite:beta-tricalcium phosphate ratios on the osteoconductivity of biphasic calcium phosphate in the rabbit sinus model. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 30, 65–72. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.3709 (2015).

Ohe, J. Y. et al. Volume stability of hydroxyapatite and beta-tricalcium phosphate biphasic bone graft material in maxillary sinus floor elevation: a radiographic study using 3D cone beam computed tomography. Clin. Oral Implants Res.27, 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12551 (2016).

Park, W. B. et al. Changes in sinus mucosal thickening in the course of tooth extraction and lateral sinus augmentation with surgical drainage: a cone-beam computed tomographic study. Clin. Oral Implants Res.34, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.14019 (2023).

Park, W. B. et al. Long-term effects of sinus membrane perforation on dental implants placed with transcrestal sinus floor elevation: a case-control study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res.23, 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.13038 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W-B. P., J-H. C. and H-C. L. designed the study.W-B. P. acquired the data.J-H. C. and S-I. S. analyzed the data.Y.H. and J-Y. H. interpretated data.W-B. P. and S-I. S. drafted the manuscript.Y.H. and H-C. L. critical revised the manuscriptAll authors approced the final manuscipt.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, WB., Herr, Y., Chung, JH. et al. Comparison of three approaches for treating the bony access window in lateral sinus floor elevation: a retrospective analysis. Sci Rep 14, 22888 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74076-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74076-2