Abstract

Root rot is a serious soil-borne fungal disease that seriously affects the yield and quality of Panxa ginseng. To develop a sustainable strategy for alleviating ginseng root rot, an herb-based soil amendment is suggested in this study. Mixed powers of medicinal herbs (MP) and corn stalks (CS) were used as soil amendments, respectively, along with a control group (CK) without treatment. The application of MP and CS led to significant relief from ginseng root rot. The disease index (%) represents both the incidence rate and symptom severity of the disease. The disease index of the MP and CS group was 18.52% and 25.93%, respectively, lower than that of CK (40.74%). Correspondingly, three soil enzyme activities improved; the antifungal components in the soil increased; and the relative abundances of root rot pathogens decreased in response to MP Soil enzyme activities were negatively correlated with disease grades. MP group also led to possible interactive changes in the communities of soil fungi and chemical components. In conclusion, our results suggest that the use of herb-based soil amendments has significant potential as an ecological and effective approach to controlling root rot disease of ginseng by the changing rhizosphere fungal community and soil compositions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer (hereinafter referred to as ginseng) is a valuable plant with high edible and medical uses1,2,3. Currently, ginseng is intensively cultivated in farmland to meet the increasing demand for medicine production. Like most crops, continuous cropping of ginseng has negative impacts on soil physicochemical properties4 and the soil microbial community5. This leads to frequently occurring soil-borne fungal diseases6. Root rot is a serious soil-borne fungal disease that limits the growth of ginseng and causes yield reductions of more than 20%7. The occurrence of root rot causes stunted plant development, resulting in dead, dry, scaly, and blackened roots. In severe cases, only the epidermal part of the root remains8. Root rot is primarily caused by the fungus genus Fusarium9, such as Fusarium oxysporum10,11, and Fusarium solani, as well as other fungi like Cylindrocarpon destructans12, Ilyonectria13 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa14. Due to the persistence and virulence, root rot can worsen the issue of replanting in the same soil.

Currently, the application of chemical pesticides is one of the most widely used methods, which reduces pests and diseases and increases crop yield15,16,17. Applying pesticides is one of the most crucial practices for disease control in ginseng cultivation. However, the commonly used chemical pesticides were not specifically designed for ginseng, so their effectiveness in controlling ginseng disease is often unstable. Furthermore, due to physicochemical properties and resistance to biodegradation, chemical pesticides are not environment-friendly18. The fungicides difenoconazole and tebuconazole, when applied to the soil, reduce the diversity and complexity of the soil bacterial community19. A similar situation also occurs in the repetition of carbendazim20. At the same time, the chemical residues in the soil and even in ginseng roots21, are harmful to the safety of medicine22. The biological control methods, including organic fertilizer, botanical pesticide and microbial agent, are eco-friendly and have the potential to reduce disease incidence while improving soil conditions23,24. It is also a possible strategy to aid or substitute chemical method25. However, its efficacy requires further investigation.

Healthy soil is one of the important environmental factors that affect plant growth26. The application of soil amendments is one of the important measures to improve the degree of soil health27, which effectively improves the soil nutrient status or the microbial community26,28 and reduces the occurrence of diseases26,29. As a kind of agricultural waste, corn stalk is widely used for soil improvement30,31,32. The corn stalk returned to the soil or used as organic fertilizer plays an important role in maintaining soil moisture33,34, increasing soil organic matter35, increasing crop grain yield, and altering micro-ecosystem of the soil36,37. Likewise, herbs with certain medicinal effects, which are easily accessible and environmentally friendly, can also be used as soil amendments. Compared to corn stalks, medicinal herbs contain antibiotic components. For example, the components of Astragalus membranaceus38 and Epimedium acuminatum39 possessed potent antifungal activity, and Osthenol showed effective antifungal activity for Fusarium40, which was similar to the function of essential oils of Cinnamomi cortex41,42. The component of Atractylodis rhizoma plays an important role in protective activity against Candida-infected mice43. The application of herbs with antibiotic components to the soil can reduce the richness of soil pathogens and thus inhibit the development of root diseases in ginseng. In addition, ginseng grown in the wild communities interacts with numerous other plants and forms a mixed population with allelopathy. The addition of herbs to the soil is a way to establish allelopathy and imitate the original habitats of wild ginsengs just like natural fostering44.

In this study, we proposed a new type of herb-based soil amendment, which is a mixed powder of herbs (astragali radix, cnidii fructus, atractylodis rhizome, epimedii folium, and cinnamomi cortex). The incidence and severity of ginseng root rot were observed and calculated, and the composition of the microbial community and the soil compositions were analyzed in response to this herb-based soil amendment. We hypothesized that the herb-based soil amendment (1) can reduce the incidence and severity of ginseng root rot and (2) result in a healthier soil community for ginseng production. Using this new type of soil amendment, the study provides a new idea of soil improvement for the alleviating of root rot in ginseng cultivation.

Results

Reduction of the incidence and severity of ginseng root rot

After harvest, we found that root rot disease was very common within ginseng planted on farmland (Fig. 1A), and the incidence of root rot was greater than 80% in each group. This accords with the previous observation6,45 that soils under continuous cropping have a high incidence of root rot. Only three ginsengs (one in each group) were completely healthy (Disease grade 0) in the three groups, and for other ginsengs, the infection was not lethal as only one ginseng in the CK group was observed at Disease grade 5 (most severe disease grade) (Fig. 1A, B). In the CK group, eight out of nine ginsengs were observed as diseased ones (~ 88.9%), and more than half are at disease grade higher than 3 with incomplete main roots (Fig. 1A, B). However, the ginsengs of CS and MP treatments were slightly infected. Both the CS and MP groups had smaller lesion areas on the ginsengs compared to that of the CK group (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the lesion areas of the MP group were smaller compared to CS and MP treatments. Most of the ginsengs in the MP group (7 out of 9, ~ 77.8%) were healthy or slightly infected at Disease grade 1, and ginsengs in the CS group were mostly moderately infected at Disease grade 2 or 3 (Fig. 1A, B). In general, the average disease grades and the disease index of ginsengs in the three groups from high to low were: CK, CS, and MP (Fig. 1C), showing that MP and CS treatments inhibit the root disease from being severe, and MP was more effective than CS.

The occurrence of root rot disease of Panax ginseng in response to MP, CS and CK treatments. Symptoms of panax ginseng root under different treatments (A). The numbers at the bottom indicate the disease grade of each ginseng. The frequency of disease grade in response to different treatments (B). The average disease grade and disease index of different treatments (C). *Disease index = ∑[(Xi × Si) / (Smax × N)] ×100%. Xi is the number of ginseng plants with disease; Si is the degree of disease; Smax is the highest degree of disease in the diseased ginseng plants; N is the total number of ginseng plants.

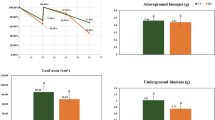

Differences in plant growth were observed between the three groups. Ginseng root diameter was reduced by ~ 22% in the CS or MP groups compared to the CK group with a statistical difference (One-way ANOVA, P < 0.05) (Tab. S1). There was no significant difference in plant height, stem diameter, root length, and root fresh weight, while these indicators have a trend toward a higher value in MP compared with CK. The intercellular CO2 concentration of CK is significantly higher than that of CS and MP (Tab. S2). There were no significant differences in the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate among the three groups.

Increases in soil enzyme activities

The responses of soil pH value, organic matter, and enzyme activities to the herb-based soil amendments were analyzed. The soil pH value and organic matters of the three groups were not significantly changed by MP or CS treatments compared to CK (Table 1). However, remarkable increases in the activities of urease, acid phosphatase, and sucrase were observed in MP and CS treatments compared to CK (Table 1).

Alteration in the composition of ginseng rhizosphere soil

Among all 985 soil compositions (SCs) identified, there were nine classes: benzenoids (BZ), lipids and lipid-like molecules (LL), nucleosides nucleotides and analogues (NN), organic acids and derivatives (OA), organoheterocyclic compounds (OC), organic nitrogen compounds (ON), organic oxygen compounds (OO), phenylpropanoids and polyketides (PP), and unclassed (UN). LL dominated the largest proportion, accounting for 10.15% of all SCs, followed by OC (9.85%) and OA (7.41%). Compared to CK, there were 50 SCs significantly affected by CS (35 increased and 15 decreased), and 51 MP (40 increased and 11 decreased) (Fig. 2A, Tab. S3). Among them, 14 SCs were significantly affected by both MP and CS treatments with the same increasing or decreasing trends (Fig. 2A).

The changes of soil compositions in response to different treatments. Venn diagram of soil compositions that were significantly different between MP and CK and between CS and CK (A). Heatmap of the 87 SCs that were significantly regulated by MP of CS compared to the CK (B). Partial least squares Discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) plots of the soil compositions (C). *The 14 SCs that were significantly affected by both MP and CS were marked in bold. On the left side of the figure ①–③ indicates different clustering modules. The majuscule at the end of the names represents different chemical composition classes. (PP = phenylpropanoids and polyketides, OC = organoheterocyclic compounds, OO = organic oxygen compounds, ON = organic nitrogen compounds, OC = organic acids and derivatives, NN = nucleosides nucleotides and analogues, LL = lipids and lipid-like molecules, B = benzenoids, UN = unclassed)

The relative contents of SCs that were significantly affected by CS or MP were shown in Fig. 2B. The compositions of the three replications of each treatment were first clustered, and MP and CS were clustered before CK (Fig. 2B), showing a closer chemical property of MP and CS than to CK. Based on each component, three clusters were observed (①–③, Fig. 2B). There were 19 SCs in Fig. 2B cluster ①, which mainly belong to PP, OC, OO, OA, BZ, and LL. The SCs in cluster ① were decreased in CS or MP groups, compared to CK group. Among them, there were seven SCs belonging to the common 14 SCs affected by both MP and CS treatments. There were 32 SCs in cluster ②, which were increased by MP or CS compared to CK, except three SCs in CS group belonging to UP and PP. These SCs belong mainly to OC, NN, PP, BZ, and UN. The last cluster ③ contained 36 SCs, which were strongly increased by CS and lightly by MP, compared to CK. These compositions belong mainly to NN, LL, OC, OA, PP, ON, BZ, and UN.

The results of the partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) (Fig. 2C) showed significant changes in the aggregation positions of the MP group and the CS group compared to the CK group, indicating that the application of plant material to the soil changed the chemical properties of the soil. The changes may also be consequences caused by soil microbes in response to the addition of plant herb-based soil amendments.

Changes in the fungal composition of ginseng rhizosphere soil

In this study, the fungal community of the soil of the ginseng rhizosphere was sequenced and analyzed. A total of 1814 OTUs were obtained from soil samples of all three treatments. The majority of soil microbes (Fig. 3A) were Ascomycota (71.29%~80.25%), Basidiomycota (4.77%~10.79%), Mortierellomycota (10.73%~6.18%), Mucoromycota (2.22%~8.17%), and Chytridiomycota (0.54%~0.10%) (Fig. 2A).

Effects of herb-based soil amendments on the richness and relative abundances of fungal communities. Fungal community compositions of rhizosphere soil under different treatments at the phylum (A) and genus level (the relative abundance of top 20 genera) (B). Heatmap of the relative abundance of top 20 genera of fungi (C). * indicate significant differences compared to the CK (T-test, P< 0.05).

Fungi in the soil samples, at the genus level, consisted mainly of Humicola (3.42 ~ 41.07%), Albifimbria (1.12 ~ 41.67%), Mortierella (4.15 ~ 12.98%), Fusarium (1.82 ~ 17.77%), and so on (Fig. 3C). Considering the relative abundances of the top 20 genera of fungi identified in samples, significant differences in the abundances of Saitozyma, Humicola, Trichoderma, Plectosphaerella were observed between the three treatments (Fig. 3B, C). Saitozyma is from the Tremellomycetes (Basidiomycota), and the other three are from Sordariomycetes (Ascomycota). After treatment of MP or CS, the relative abundances of Athelia, Fusarium, Plectosphaerella, and Pseudogymnoascus were reduced in the rhizosphere compared to those in CK (Fig. 3B, C). The relative abundances in CK, CS, and MP group were 7.85%, 4.97%, and 6.03%, respectively. On the contrary, the relative abundances of Trichoderma, Pseudopithomyces, Albifimbria, and Chaetomium were increased in response to MP or CS treatment than CK (Fig. 2B, C). In the MP group, the relative abundances of Mortierella, Humicola, Trichoderma, Pseudopithomyces, and Sampaiozyma were higher than those of CK and CS, and the relative abundance of Alternaria and Saitozyma was lower than those of CK and CS (Fig. 3B, C).

Shifts in fungal diversity of ginseng rhizosphere soil

The diversity indices of Ace, Chao, Shannon, and Simpson were calculated to analyze the richness and diversity of the soil fungal communities in response to the application of herb-based soil amendments (Table 2). The Simpson and Shannon indices of MP or CS were lower than those of the CK, but the differences were not significant at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA. The Chao1 and ACE indices of MP were significantly lower than those in CK. This indicated a reduction in fungal diversity in response in MP and CS treatments to the soil.

Data of relative abundances of all samples were used to generate a dendrogram using an unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) cluster analysis (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4A, the samples were clustered under their respective component branches, indicating that the differences between the treatments in the samples were greater than the differences within each treatment. Thus, the composition of the fungal community in the rhizosphere of ginseng strongly affected the soil amendments. This was also supported by the partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) (Fig. 4B), in which the fungal communities were well separated into three main groups of CK, MP, and CS.

Soil fungal diversity of rhizosphere soil and biomarkers in response to different treatments. UPGMA cluster analysis of soil fungal community (A). PLS-DA analysis of the fungal OTUs in CK, CS, and MP soils (B). LEfSe analysis of all fungi (C). *The yellow node represents the species with no significant difference of relative abundance in different soils. The node diameter is proportional to the relative abundance, and each layer node represents domain, phylum, class, order, family, and genus from the inside to outside. LDA > 3.5)

The result of the LEfSe analysis of the contribution of species is shown in Fig. 4C (LDA score > 3.5). LEfSe analysis is used to analyze the differences between treatments and to find out the main groups of fungi, which are helpful for developing biomarkers for different treatments. The CK group contained six rich fungal branches, including Trametes, Polyporaceae, Plectosphaerella, Simplicillium, Mycenella, and Pseudocercospora (Fig. 4C). The CS group contained seven rich fungal branches, including genera of Agaricales, Bolbitiaceae, Diloszegia, which were of the Agaricus order, and other four fungi of different genera Waitea, Conocybe, Stachybotrys, and Curvularia. The MP group contained three rich fungal branches of Sordariomycetes, Sordariales, and Chaetomiaceae. Coincidentally, they all belong to the Sordariomycetes.

Functional changes in the fungal community of ginseng rhizosphere soil

FUNGuild was used to predict the functional and trophic modes of the specific fungal community. In the Trophic mode of Funguild (Fig. 5A), the highest proportion was Pathotroph-Saprotroph-Symbiotroph 16.47–24.32%. In the Guild mode of FUNGuild, the functional prediction of the fungal communities of the MP treatment was mainly related to the Animal Pathogen (15.4%), followed by the Endophyte (12.2%) and the Plant Pathogen (2.8%). In response to CS treatment, three main species in function prediction of fungal communities are the Animal Pathogen (15.8%), the Plant Pathogen (8.9%), and the Endophyte (7.3%). The functional prediction of the fungal communities of CK is mainly related to the Animal Pathogen (17.9%), the Endophyte (9.2%), the Plant Pathogen (8.2%), and the Epiphyte (4.7%), suggesting that the existence of the Animal Pathogen and the Epiphyte may aid the plant pathogen in infecting the hosts. In the Guild mode of FUNGuild (Fig. 5B), there were significant differences in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal, Dung Saprotroph, Ectomycorrhizal, Lichen Parasite, and Soil Saprotroph among the three treatments. There were no significant differences between CK and CS in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal, and Dung Saprotroph, but the relative abundance of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal, and Dung Saprotroph in CK was significantly higher than that of MP. The relative abundance of Soil Saprotroph was significantly lower in CS and MP than in CK. In the classification of Ectomycorrhizal, the relative abundance of CS was significantly higher than that of MP. The relative abundance of Lichen Parasite in CS was significantly higher than that of CK and MP.

Correlation of soil properties, fungal community, and soil composition

As shown in Fig. 6A, there was a positive correlation found in the activities of the three soil enzymes (urease, sucrase, and acid phosphatase), and they were negatively correlated to the disease severity. This indicated that the occurrence of root rot was related to low soil enzyme activity. The organic matter of the soil was positively correlated with the activities of the three enzymes (Fig. 6A), showing the relationship between soil fertility and soil enzyme activity. The activities of the three soil enzymes were also negatively correlated with Chao1 index, ACE, and root diameter (Fig. 6A), suggesting an interaction between soil enzyme activity and fungus abundance. In addition, a negative correlation between fresh weight of root and Simpson and Shannon Indexes was observed (Fig. 6A).

Correlation analysis between soil environmental factors, fungi communities, and oil compositions. Correlation Analysis of soil environmental factors (person, P < 0.05) (A). Heatmap fungal communities (genus, top 20 of relative abundance) and the classes of soil compositions that are significantly affected by MP or CS (person) (B). * refers to the significant difference with P < 0.05. ** refers to the significant difference with P < 0.01. *** refers to the significant difference with P< 0.001.

A correlation analysis of the top 20 relative abundant genera of fungi in all three treatments and all classes of the SCs differentially affected by MP or CS treatments was conducted (Fig. 6B). The genera of Albifimbria, Conocybe, Rhizopus, and Waitea, the abundances of which were significantly higher in CS than in CK (Fig. 3C), were positively correlated with OC, ON, OA, NN, and BZ (Fig. 6B). In addition, the abundances of Coniochaeta and Paraphaeosphaeria, which were significantly lower in CS than in CK or MP, were negatively correlated with BZs (Fig. 6B). The abundances of Ilyonectria, Plectosphaerella, and Pseudogymnoascus were positively correlated with OO and LL (Fig. 6B). The abundances of Mortierella, Humicola, Pseudopithomyces, and Saitozyma, which were higher in MP than in CK, showed a positive correlation with PP and other UNs (Fig. 6B). These results suggested an interaction affected by MP treatment between SCs and microorganisms.

Discussion

Many studies demonstrated the benefits of using herb-based soil amendments, as they can improve soil nutrients, repair soil, and inhibit pathogenic microorganisms by altering soil properties46,47,48. The addition of humic acid improved the yield and quality of continuous cropping peanut due to the improved physicochemical properties and enzymatic activities of the soil49. However, herb-based materials with medicinal functions were rarely used as soil amendments for cultivation. In this study, the most significant changes in ginsengs were the alleviation of root rot after the application of the herb-based soil amendments. The soil amendments significantly reduced the incidence and severity of ginseng root rot. Specifically, MP treatment resulted in a reduction in the disease index by 54.5% of ginseng root rot.

The herbs of MP contain a variety of components, like flavonoids(astragali radix50, cinnamomi cortex51, epimedii folium52), saponins (astragali radix50), phenylpropanoid (cinnamomi cortex53), terpenoids (atractylodis rhizoma54), organic acid (epimedii folium55, cinnamomi cortex56), and so on. And the application of these herbs altered the soil. After MP and CS treatments, soil organic matter tended to increase (Table 1), indicating a higher soil fertility. MP promoted the composition of OC, OA, and PP in the soil and decreased BZ and PP in the soil. Especially, coumarins and isoflavonoids (which belong to PP) were notably increased by MP. Coumarins were growth promotion stimulators observed among the high abundance factors responding to abiotic stress in inoculated mulberry57. Similarly, in the study of chlorine dioxide repressed potato germination, the upregulated SCs were composed mainly of coumarins57. These results suggest that increased antifungal components are beneficial for reducing the occurrence of ginseng root rot. Interestingly, the contents of carbendazim (which belong to OC) and flavonoids (which belong to PP) in MP were significantly reduced Carbendazim is an organoheterocyclic fungicide and is widely used throughout the world, however, with the risks of causing environmental pollution58. Flavonoids are reported to have inhibition effects on Fusarium59. The decrease in carbendazim in MP treatment suggested that the addition of herbal powders could reduce the chemical risks to the environment by the degradation of carbendazim, and inhibit the occurrence of root rot in other ways. Despite the decrease in antifungal substances, such as flavones and triterpenoids, the disease index of MP is lower than that of CK group. Therefore, we speculate that the use of herb-based soil amendment is beneficial to the soil by increasing antifungal ingredients. Pteridines and derivatives (which belong to OC) and phenolic compounds (which belong to BZ) produced in plants were improved by salt stress60 or water stress61 with antifungal activities. Therefore, the increase in phenolic compounds, commonly involved in plant’s biotic stress as defensive responses62, in this study suggests that adding herb-based soil amendment was conducive to the response to stress from a deteriorating environment.

Although soil organic matter improved in the MP group (Table 1), ginseng growth was not strongly affected by adding soil amendments. The root diameter of CK group was larger than that of MP group (Tab. S1), which may be a compensatory increase. The root length and root fresh weight of MP group tended to increase after MP treatment (Tab. S1, not significantly). This suggested that the herb-based soil amendments contributed to the longitudinal growth of the main root of ginseng.

By the application of herb-based soil amendments, the fungal diversity was changed. The values of the Shannon Index and Simpson index were not significantly affected, but values of Chao1 index and Ace index were decreased significantly (Table 2). The Chao1 and Ace indices mainly represented the abundance of the fungal community63. Thus, the richness of fungal community was reduced by MP amendment, while the incidence and severity of ginseng root rot was also reduced by MP treatment. Thus, we assume that herb-based soil amendments reduced pathogenic fungi, resulting in a healthier soil environment for ginseng growth. Based on our results, the relative abundances of Fusariums and Ilyonectria decreased in MP group. The genera Fusariums and Ilyonectria are among the most common fungal genera in the ginseng rhizosphere64 and are reported to be the pathogenic fungi of ginseng root rot65,66. The relative abundances of Fusariums and Ilyonectria in MP grouop were lower than those in CK group in this study (Fig. 3), and this could be the reason for the alleviation of root rot, as the abundance of Fusarium was positively correlated with the incidence of plant disease67,68.

Based on the UMPGA cluster tree and the PLS-DA analysis, herb-based soil amendments significantly affected the composition of the soil fungal community, as evidenced by the reduction of functional abundance predicted by FUNGuild (Fig. 5A). The Soil Saprotroph and Dung Saprotroph of the Guild mode of FUNGuild were reduced by the application of MP (Fig. 5B), and thus we assumed that Soil Saprotroph and Dung Saprotroph were related to the decay and the spread of plants infected by pathogens. Fusarium was not only the soil saprotroph, but also known as phytopathogens that cause rot root in various plants67,69,70. The abundances of llyonectria and Plectosphaerella decreased in MP compared to CK (Fig. 3B). This suggested that the application of MP inhibited the abundance of pathogenic fungi, which is in accordance with the results of function prediction of the fungi community.

Biomarkers found by the analysis of LEfSe (Fig. 4C) helped to identify key fungal communities between treatments. The biomarkers in MP have obvious subordination, suggesting that attention should be paid to Sordariomycetes, Sordariales, and Chaetomiaceae. It may also be related to the improvement of plant resistance and the reduction of disease occurrence. The isolated endophytic fungi from R. roxburghii suggested that endophytic Sordariomycetes from R. roxburghii were potential sources to explore antimicrobial agents71. Maize soils in different cropping patterns show that Sordariales is more abundant in the organic farming system than the conventional farming system72. Sordariales have been reported with antifungal activities in the study of fungal community succession across a gradient from bulk soil to the plant endosphere of diseased and healthy lisianthus73. Hung et al.74 reported that the application of Chaetomiaceae spores to pomelo seedlings inoculated with Phytophthora nicotianae reduced the extent of root rot and increased plant weight. Chaetomiaceae was significantly enriched in non-continuous cropping soil compared to continuous-cropping soil75. Thus, the application of MP materials to soil promotes the growth of Sordariomycetes, Sordariales, and Chaetomiaceae, which inhibit the growth of fungi, aiding the reduction of the occurrence of root rot. After the application of corn stalks, seven biomarkers were identified by LEfSe analysis. Among them, three were of Agaricus order and were mainly involved in the decomposition and maintenance of the organic balance of the soil. The addition of corn straw to the soil can promote the circulation and utilization of soil organic matter76,77, and this therefore benefits plant growth. Interestingly, according to the results of the LEfSe analysis, Pseudocercospora from Ascomycota was identified only in the soil of the CK Group, and not in the soil of the other two treatments. The fungi of this genus are the pathogens of Sigatoka disease78. Therefore, the biomarkers of the CK soil were pathogenic fungi, indicating there were more pathogenic fungi in the continuously cultivated soil of ginseng.

The interactions between soil nutrient content, enzyme activity, and microbial biomass jointly regulate plant growth79. In this study, we found a significant correlation between the activities of the soil enzymes of sucrase and acid phosphatase, and they were negatively correlated with the occurrence of root rot disease grade(Fig. 6A). The increase of soil enzyme activities is beneficial to the soil nutrient cycling, and improves the microbial environment to reduce root diseases79,80. Therefore, the addition of herb-based soil amendments has the potential to inhibit ginseng root rot by increasing soil enzyme activities. Although significant changes in root fresh weight were not observed, a negative correlation was observed between root fresh weight and Simpson and Shannon Indices (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that the higher the diversity of soil rhizosphere fungi, the more unfavorable it is to increase the fresh weight of the roots. The direct effect of fungal diversity on ginseng growth is still not clear, and the correlation is related to the increase in pathogen species of rhizosphere fungi, leading to an increase in root rot disease.

Enzymatic activities are expected to enhance soil nutrient availability in order to meet the demand for microbial metabolism81,82. Abundant nutrients attract more microorganisms and simultaneously increase soil enzyme activity83. Soil sucrase promotes saccharose catabolism, which provides a carbon source for microbes, thus promoting their growth84. Urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbonic acid, and plays an important role in the nitrogen cycling driven by soil microorganisms85. Acid phosphatase secreted by soil microorganisms plays a critical role in soil P cycle and determines the availability of this element86. The altered soil properties and enzyme activity inevitably affected soil microorganisms and plant roots87. Therefore, the significantly increased activities of sucrase, urease, and acid phosphatase in this study are supposed to be related to the increase in available nutrients in the soil, such as saccharose, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, which play important roles in the promotion of plant root growth. Furthermore, the enzyme activity, plant growth, and the accumulation of beneficial soil microorganisms formed a benign cycle, which improved the level of soil health and reduced the occurrence of root rot.

The changes in soil chemical compounds were highly correlated with the changes in the abundance of soil fungi in response to the application of CS (Figs. 3C and 6). The abundances of Alternaria, Sampaiozyma, Phizopus, Aspergillus, Waitea, Conocybe, Chaetomium and Albifimbria showed an increasing trend in response to CS treatment (Fig. 3C), and were positively related to the composition of OC, ON, OA NN, and BZ (Fig. 6). ON and NN are important bioactive compounds in favor of plant growth88,89. OA90 and BZ91 have been proven to play roles in stress resistance or antifungal activity in plants. The relative abundances of Mortierella, Humicola, Saitozyma, Trichoderma, and Pseudogymnoascus increased with the application of MP (Fig. 3C). They are known to inhibit plant pathogens92, decompose dead plant biomass93, and degrade phenylurea herbicides94. The increase in the relative abundances of these fungi was beneficial in reducing the pathogenic fungus and increasing the soil organic matter. Meanwhile, they were positively correlated with the compositions of PP and UN, and were not significantly or tended to be correlated with other SCs. In particular, among the soil compositions correlated to the MP-induced fungi, UNs were of a great proportion. This indicated that the changes in SCs caused by MP treatment were unclear to a great extent and needed further investigation. These unclassed compounds have the potential to be the key substance that limits the spread and severity of ginseng root rot.

In this study, a type of herb-based soil amendment was suggested, and it effectively alleviated ginseng root rot in continuous cropping soil. The following effects were observed by the application of the herb-based soil amendment: (1) significantly increased soil enzyme activity; (2) decreased the pathogenic fungi community in soil; and (3) increased SCs with antifungal activity of the rhizosphere soil. Our findings suggest that the use of herb-based soil amendments has significant potential as a sustainable and effective approach for root rot prevention and control in ginseng. It provides a new strategy for ecological planting on the reduction of using chemical pesticides. However, only five herbs with equal proportions were used in this experiment and the effects of other antifungal herbs with unequal proportions are worth investigation. Additionally, this experiment was conducted in pots with continuous cropping soil. Further research should focus on refining the application of herb-based soil amendments in field conditions and elucidating the mechanisms underlying their suppressive effect on soil-borne diseases, which can benefit the cultivation of ginseng on the farmland, solving the continuous planting issue.

Materials and methods

Study sites and study design

The experiment was carried out in Jingyu County, Jilin Province (126.8 °E, 42.39 °N). The area belongs to the monsoon climate zone. The annual average temperature was 2.6 °C, the annual average precipitation was about 827 mm, and the average annual sunshine hours were about 2300 h. Chernozem soil that had been used for continuous ginseng cultivation for 4 years was collected in the field and then placed in the open air for 6 months before this experiment. The physical and chemical properties of the soil are as follows: organic matter content = 58.87 g kg−1, pH = 5.75, total nitrogen content = 2.6 g kg−1, total phosphorus content = 1.15 g kg−1, total potassium = 15.67 g kg−1, alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen = 234.82 mg kg−1, available phosphorus = 7.43 mg kg−1, available kalium133.67 mg kg−1.

Forty-five 4-year-old healthy ginsengs (provided by Baishan Lincun Traditional Chinese Medicine Co., Ltd.) were dug from the field and potted (one ginseng per pot; the pot is 25 cm in height with diameter of 22 cm). These pots were placed under sunshade cloths in the field(the same environment as filed grown ginsengs) on June 21st 2022. The distance from the arched top of the sunshade cloths to the ground surface was 2.5 m. And the openings were designed on the bottom (without sunshade cloths from ground to 70 cm) to improve internal ventilation conditions. The grown environment of the potted ginsengs was the same as ginsengs cultivated in the farmland. The potted ginsengs were divided into 3 groups, with 15 of each. One group was used for herb material treatment (MP), one for corn stalk treatment (CS), and the other group was used as control without treatments. Before potting, 5 kg of soil was added to each pot. For the MP group, the soil in each pot was mixed with powders (10 g of each) of astragali radix, cinnamomi cortex, cnidii fructus, atractylodis rhizoma and epimedii folium (Tab. S4). All these plant materials are commercially used as Chinese herbal medicine (China Pharmacopoeia Committee, 202095), and were purchased from an herbal medicine pharmacy (Anguo Wanzongtang Traditional Chinese Medicine Co., Ltd.). The main chemical composition of herbal mixture in MP treatment includes: (1) flavonoids, including formononetin, calycosin, ononin, icariin, epimedin; (2) phenylpropanoids, including cinnamyl alcohol, cinnamaldehyde, osthole, bergapten, imperatorin; (3) terpenoids, including atractylodin, atractylone, atractylenolide; (4) saponins, including astragalosides; (5) saccharides, including astragali radix polysaccharides, atractylodis rhizoma polysaccharide; (6) organic acids, including cinnamic acid. The confirmation and quality control of these herbal medicines were based on the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. For the CS group, the particle size was 2 cm, and 100 g of dry corn stalk (Jiangsu Surui Straw Processing Factory), were added and mixed with the soil in each pot. The dosage was mostly based on previous planting experience of ginseng96,97, that 6–8 kg/m2 was recommended. The CS dosage used in this study was calculated accordingly, that 100 g per pot approximately equaled to 6.58 kg/m2 of the field dosage. All ginsengs were collected on September 21st 2022. After potting, all pots were placed in the field. The grown environment of the potted ginsengs was the same as ginsengs cultivated in the field. The irrigation, fertilization, pest control, and soil management were consistent with local production practices.

Measurement of plant and the gas exchange

Plant height and stem diameter of each plant were also measured on the 60th day after transplanting. Six plants were randomly selected from each group and the net photosynthesis, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and substomatal CO2 concentrations were measured on the largest leaf of each plant using LI-6800 (LI-COR, USA). The built-in red and blue light source was set to be 300 µmol m−2 s−1. The CO2 concentration in the blade chamber is controlled by the carbon dioxide cylinder, and the specific numerical value was set at 400 µmol mol−1. The temperature of the blade chamber was set at 29 °C, the relative humidity was set at 55%, and the flow rate was set at 500 µmol s−1.

Collection of plant and soil materials

Nine plants randomly selected from each group were collected on September 21st 2022. The length, diameter, and fresh weight of the main root of each ginseng were recorded. Meanwhile, soil samples from the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere of each ginseng were collected respectively. The non-rhizosphere soil of each ginseng was divided into two parts after evenly stirring in the pot. For the first part of the non-rhizosphere soil of 9 ginsengs, every three samples were mixed into one, and the 3 mixed samples were air dried for the determination of soil organic matter and pH value. For the second part of the non-rhizosphere soil of 9 ginsengs, 5 randomly selected samples were stored at 4 °C to determine the enzyme activity of the soil. The root-attached soil of ginseng was regarded as rhizosphere soil and sampled after gently shaking the root system. All soils in the rhizosphere were collected within 5 mm of the surface of each root. The rhizosphere soils were from the 9 randomly selected plants, every 3 mixed into one sample. Rhizosphere soil samples were transported back to the laboratory in refrigerated containers at −78.5 °C and stored at −80 °C for the analysis of soil fungal community and soil compositions.

Determination of root rot disease index

The severity of root rot in ginseng was visually assessed on a scale of 0 to 5 (Fig. S1) as follows: 0 (healthy roots); 1 (< 1/5 of the root surface decayed or the fiber root was slightly decayed); 2 (~ 1/5 of the root surface decayed or >1/5 of the fiber root decayed); 3 (~ 1/3 of the main root surface decayed or >1/3 of the fiber root decayed/missing); 4 (~ 1/2 of the main root surface decayed/missing or >1/2 of the fiber root decayed/missing); 5 (> 1/2 of the main root surface and interior decayed, the main root is incomplete or without fiber roots).

The disease index was calculated as follows98:

Xi is the number of ginseng plants with disease; Si is the degree of disease; Smax is the highest degree of disease in the diseased ginseng plants; N is the total number of ginseng plants.

Determination of soil properties and soil enzyme activities

Soil organic matter was detected using an external heating method with potassium dichromate-concentrated sulfuric acid99. The power of hydrogen in the soil (pH) was detected using a PB-10 pH meter (Sartorius AG, Germany). Soil urease activity was assessed by colorimetric analysis of sodium phenate-sodium hypochlorite100. Sucrase activity was determined using the colorimetric method with 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid100. Acid phosphatase activity was estimated using the disodium phenylphosphate colorimetric method100.

Soil composition analysis

Soil samples were frozen dried using H1650-W (Eppendorf, Germany) prior to extraction. Samples were extracted by 1000µL of methanol, and the supernatant was concentrated to dry in vacuum. The samples were then dissolved with 150µL 2-chlorobenzalanine 80% methanol solution, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. The extracted samples were used for LC-MS detection. Soil composition analysis was performed at Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Chromatographic separation was performed using a Thermo Ultimate 3000 system that was equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC® HSS T3 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The ESIMSn experiments were executed using the Thermo Q Exactive mass spectrometer with a spray voltage of 3.8 kV and − 2.5 kV in positive and negative modes, respectively. The sheath and auxiliary gases were set at 30 and 10 arbitrary units, respectively. The capillary temperature was 325 ◦C. The analyzer scanned over a mass range of m/z 81–1000 for the full scan at a mass resolution of 70,000. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) MS/MS experiments were performed by an HCD scan. The normalized collision energy was 30 eV. Unnecessary information in the MS/MS spectra was removed by dynamic exclusion.

The correlation analysis of the components between treatments was performed by R and the heatmap was drawn by the R package pheatmap101. For a preliminary visualization of differences between different groups of samples, the unsupervised dimensionality reduction method principal component analysis (PCA) was applied in all samples using R package models102. The correlation heatmap was drawn using R corrplot package103.

Soil fungal community analysis

The microbial DNA was extracted using HiPure Soil DNA Kits (Magen, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The rDNA target region of the ribosomal RNA gene was amplified by PCR using primers ITS_1F_KYO2 (5′-TAGAGGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAA-3′) and ITS86R (5′-TTCAAAGATTCGATGATTCAC-3′). The rDNA target region of the ribosomal RNA gene was amplified by PCR. The amplicons were purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, U.S.) and quantified using the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA). The purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar and paired-end sequenced (PE250) on an Illumina platform according to the standard protocols. The raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number PRJNA1035276.

Raw data containing adapters or low-quality reads were filtered using FASTP104 (version 0.18.0). Clean tags were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of ≥ 97% similarity using UPARSE105 (version 9.2.64) pipeline. All chimeric tags were removed using the UCHIME algorithm104 and finally obtained effective tags for further analysis. The stacked bar plot of the community composition was visualized in the R project ggplot2 package106 (version 2.2.1). The heatmap of species abundance was plotted using pheatmap package (version 1.0.12)101 in R project. The biomarker features in each group were screened by LEfSe software107 (version 1.0) in R project. The functional group (guild) of the Fungi was inferred using FUNGuild108 (version 1.0).

Statistical data analysis

Data reported in this study were analyzed using IBM SPSS 27 software (IBM, USA). To determine whether there were significant differences between the treatment and control groups, ANOVA was performed. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. The graphs were drawn with Origin 2021 Pro (Origin, USA), and the image typesetting was performed with Adobe Photoshop 2023 (Adobe, USA).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Raw microbiome metagenomic sequences are available under the identification PRJNA1035276 in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive.

References

Yun, T. K. Panax ginseng—A non-organ-specific cancer preventive? Lancet Oncol. 2, 49–55 (2001).

Wang, X. S., Hu, M. X., Guan, Q. X., Men, L. H. & Liu, Z. Y. Metabolomics analysis reveals the renal protective effect of Panax ginseng C. A. Mey in type 1 diabetic rats. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 20, 378–386 (2022).

He, M. et al. The difference between white and red ginseng: Variations in ginsenosides and immunomodulation. Planta Med. 84, 845–854 (2018).

Chen, P. et al. Phase changes of continuous cropping obstacles in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) production. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 155, 103626 (2020).

Arafat, Y. et al. Long-term monoculture negatively regulates fungal community composition and abundance of tea orchards. Agronomy 9, 466 (2019).

Song, X. et al. Characteristics of soil fungal communities in soybean rotations. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 926731 (2022).

Farh, M. E. A. et al. Pathogenesis strategies and regulation of ginsenosides by two species of Ilyonectria in Panax ginseng: Power of speciation. J. Ginseng Res. 44, 332–340 (2020).

Rahman, M. & Punja, Z. K. Factors influencing development of root rot on ginseng caused by Cylindrocarpon destructans. Phytopathology 95, 1381–1390 (2005).

Baudy, P. et al. Environmentally relevant fungicide levels modify fungal community composition and interactions but not functioning. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117234 (2021).

Lee, S. G. Fusarium species associated with ginseng (Panax ginseng) and their role in the root-rot of ginseng plant. Res. Plant. Dis. 10 (2004).

Li, Q., Yan, N., Miao, X., Zhan, Y. & Chen, C. The potential of novel bacterial isolates from healthy ginseng for the control of ginseng root rot disease (Fusarium oxysporum). PLoS One. 17, e0277191 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Transcriptome analyses of the ginseng root rot pathogens Cylindrocarpon destructans and Fusarium solani to identify radicicol resistance mechanisms. J. Ginseng Res. 44, 161–167 (2020).

Farh, M. E. A. et al. Discovery of a new primer set for detection and quantification of Ilyonectria mors-panacis in soils for ginseng cultivation. J. Ginseng Res. 43, 1–9 (2019).

Gao, J., Wang, Y., Wang, C. W. & Lu, B. H. First report of bacterial root rot of ginseng caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in China. Plant. Dis. 98, 1577 (2014).

Cheng, H. et al. Bio-activation of soil with beneficial microbes after soil fumigation reduces soil-borne pathogens and increases tomato yield. Environ. Pollut. 283, 117160 (2021).

Li, B., Wang, S., Zhang, Y. & Qiu, D. Acid soil improvement enhances disease tolerance in citrus infected by Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3614 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Microbial fertilization improves soil health when compared to chemical fumigation in sweet lily. J. Fungi (Basel) 8, 847 (2022).

Cha, K. M. et al. Canola oil is an excellent vehicle for eliminating pesticide residues in aqueous ginseng extract. J. Ginseng Res. 40, 292–299 (2016).

Han, L., Kong, X., Xu, M. & Nie, J. Repeated exposure to fungicide tebuconazole alters the degradation characteristics, soil microbial community and functional profiles. Environ. Pollut. 287, 117660 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Response of soil bacterial community to repeated applications of carbendazim. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 75, 33–39 (2012).

Xiao, J. et al. Analysis of exposure to pesticide residues from traditional Chinese medicine. J. Hazard. Mater. 365, 857–867 (2019).

Ryu, H. et al. Biological control of Colletotrichum panacicola on Panax ginseng by Bacillus subtilis HK-CSM-1. J. Ginseng Res. 38, 215–219 (2014).

Song, M., Yun, H. Y. & Kim, Y. H. Antagonistic Bacillus species as a biological control of ginseng root rot caused by Fusarium cf. incarnatum. J. Ginseng Res. 38, 136–145 (2014).

Tian, G. et al. Application of vermicompost and biochar suppresses Fusarium root rot of replanted American ginseng. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105, 6977–6991 (2021).

Niem, J. M., Billones-Baaijens, R., Stodart, B. & Savocchia, S. Diversity profiling of grapevine microbial endosphere and antagonistic potential of endophytic Pseudomonas against grapevine trunk diseases. Front. Microbiol. 11, 477 (2020).

Shen, G., Zhang, S., Liu, X., Jiang, Q. & Ding, W. Soil acidification amendments change the rhizosphere bacterial community of tobacco in a bacterial wilt affected field. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 9781–9791 (2018).

Hammerschmiedt, T. et al. Assessing the potential of biochar aged by humic substances to enhance plant growth and soil biological activity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 8, 46 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Structural and predicted functional diversities of bacterial microbiome in response to sewage sludge amendment in coastal mudflat soil. Biology (Basel) 10, 1302 (2021).

Andreo-Jimenez, B. et al. Chitin- and keratin-rich soil amendments suppress Rhizoctonia Solani disease via changes to the soil microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e00318–e00321 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Straw soil conditioner modulates key soil microbes and nutrient dynamics across different maize developmental stages. Microorganisms 12, 295 (2024).

Xin, J., Yan, L. & Cai, H. Response of soil organic carbon to straw return in farmland soil in China: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 359, 121051 (2024).

Song, D. et al. Soil nutrient and microbial activity responses to two years after maize straw biochar application in a calcareous soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 180, 348–356 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Impact of straw management on seasonal soil carbon dioxide emissions, soil water content, and temperature in a semi-arid region of China. Sci. Total Environ. 652, 471–482 (2019).

Zhang, J. Study on the effect of straw mulching on farmland soil water. J. Environ. Public Health 3101880 (2022).

Zhang, W., Yang, S., Chang, A., Jia, L. & E, J. Effects of straw mulching combined with nitrogen application on soil organic matter content and atrazine digestion. Sci. Rep. 12, 15909 (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. Comparison of the responses of soil fungal community to straw, inorganic fertilizer, and compost in a farmland in the loess plateau. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0223021 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Wang, N., Yu, M., Yu, J. & Xue, L. Rhizosphere and straw return interactively shape rhizosphere bacterial community composition and nitrogen cycling in paddy soil. Front. Microbiol. 13, 945927 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Insulin-modulating, insecticidal, and antifungal cysteine-rich peptides from Astragalus Membranaceus. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 194–204 (2019).

Cheng, H. et al. Extraction, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Epimedium Acuminatum Franch. Polysaccharide. Carbohydr. Polym. 96, 101–108 (2013).

Montagner, C. et al. Antifungal activity of coumarins. Z. Naturforsch C J. Biosci. 63, 21–28 (2008).

Brnawi, W., Hettiarachchy, N., Horax, R., Kumar-Phillips, G. & Ricke, S. Antimicrobial activity of leaf and bark cinnamon essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella typhimurium in broth system and on celery. J. Food Process. Preserv. 43, e13888 (2019).

Perczak, A. et al. Antifungal activity of selected essential oils against Fusarium Culmorum and F. Graminearum and their secondary metabolites in wheat seeds. Arch. Microbiol. 201, 1085–1097 (2019).

Inagaki, N. et al. Acidic polysaccharides from rhizomes of atractylodes lancea as protective principle in Candida-infected mice. Planta Med. 67, 428–431 (2001).

Li, X. et al. Sustainable utilization of traditional Chinese medicine resources: Systematic evaluation on different production modes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 218901 (2015).

Xiao, C., Yang, L., Zhang, L., Liu, C. & Han, M. Effects of cultivation ages and modes on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere soil of Panax ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 40, 28–37 (2016).

Liu, B. et al. Comparison of efficacies of peanut shell biochar and biochar-based compost on two leafy vegetable productivity in an infertile land. Chemosphere 224, 151–161 (2019).

Noronha, F. R., Manikandan, S. K. & Nair, V. Role of coconut shell biochar and earthworm (Eudrilus Euginea) in bioremediation and palak spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) growth in cadmium-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manage 302, 114057 (2022).

Yusoff, S. F. et al. Antifungal activity and phytochemical screening of vernonia amygdalina extract against botrytis cinerea causing gray mold disease on tomato fruits. Biology (Basel) 9, 286 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Humic acid fertilizer improved soil properties and soil microbial diversity of continuous cropping peanut: a three-year experiment. Sci. Rep. 9, 12014 (2019).

Song, S. S. et al. Role of simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on biotransformation and bioactivity of astragalosides from Radix Astragali. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 231, 115414 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Development of an ionic liquid-based microwave-assisted method for simultaneous extraction and distillation for determination of proanthocyanidins and essential oil in cortex cinnamomi. Food Chem. 135, 2514–2521 (2012).

Hou, M. et al. Icariside I reduces breast cancer proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis probably through inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 76, 499–513 (2024).

Yuan, P., Shang, M. & Cai, S. Study on fingerprints of chemical constituents of cinnamomi ramulus and cinnamomi cortex. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 37, 2917–2921 (2012).

Zhao, Y. et al. Predictive analysis of quality markers of atractylodis rhizoma based on fingerprint and network pharmacology. J. AOAC Int. 106, 1402–1413 (2023).

Liu, X., He, X. Y., Liu, B. L. & Song, P. S. Determination of 13 chemical components of Epimedii Folium in pharmacopoeia by UPLC method combined with quantitative analysis of multicomponents by single-marker. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 49, 981–988 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Identification of differential compositions of aqueous extracts of cinnamomi ramulus and cinnamomi cortex. Molecules 28, 2015 (2023).

Zheng, X. et al. Integrated analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals the mechanism of chlorine dioxide repressed potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber sprouting. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 887179 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. Ecological risks, toxicities, degradation pathways and potential risks to human health. Chemosphere 314, 137723 (2023).

Förster, C. et al. Biosynthesis and antifungal activity of fungus-induced O-methylated flavonoids in maize. Plant. Physiol. 188, 167–190 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Salt stress improves thermotolerance and high-temperature bioethanol production of multi-stress-tolerant Pichia kudriavzevii by stimulating intracellular metabolism and inhibiting oxidative damage. Biotechnol. Biofuels 14, 222 (2021).

Rajha, H. N. et al. A comparative study of the phenolic and technological maturities of red grapes grown in Lebanon. Antioxid. (Basel) 6, 8 (2017).

Kumar, D., Yusuf, M. A., Singh, P., Sardar, M. & Sarin, N. B. Modulation of antioxidant machinery in α-tocopherol-enriched transgenic Brassica juncea plants tolerant to abiotic stress conditions. Protoplasma 250, 1079–1089 (2013).

Liao, C. et al. Effect of lactic acid bacteria, yeast, and their mixture on the chemical composition, fermentation quality, and bacterial community of cellulase-treated Pennisetum sinese silage. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1047072 (2022).

Goodwin, P. H. The rhizosphere microbiome of ginseng. Microorganisms. 10, 1152 (2022).

Guan, Y. M. et al. Multi-locus phylogeny and taxonomy of the fungal complex associated with rusty root rot of Panax ginseng in China. Front. Microbiol. 11, 618942 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Regulating root fungal community using mortierella alpina for fusarium oxysporum resistance in Panax ginseng. Front. Microbiol. 13, 850917 (2022).

Shen, Z. et al. Banana Fusarium wilt disease incidence is influenced by shifts of soil microbial communities under different monoculture spans. Microb. Ecol. 75, 739–750 (2018).

Zhou, D. et al. Deciphering microbial diversity associated with Fusarium wilt-diseased and disease-free banana rhizosphere soil. BMC Microbiol. 19, 161 (2019).

Coleman, J. J. The Fusarium solani species complex: ubiquitous pathogens of agricultural importance. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 17, 146–158 (2016).

Chen, S., Yu, H., Zhou, X. & Wu, F. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedling rhizosphere Trichoderma and Fusarium Spp. communities altered by vanillic acid. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2195 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Multigene phylogeny, diversity and antimicrobial potential of Endophytic Sordariomycetes from Rosa roxburghii. Front. Microbiol. 12, 755919 (2021).

Ares, A. et al. Effect of low-input organic and conventional farming systems on maize rhizosphere in two portuguese open-pollinated varieties (OPV), ‘Pigarro’ (Improved Landrace) and ‘SinPre’ (a composite cross population). Front. Microbiol. 12, 636009 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Plant pathological condition is associated with fungal community succession triggered by root exudates in the plant-soil system. Soil Biol. Biochem. 151, 108046 (2020).

Hung, P. M., Wattanachai, P., Kasem, S. & Poeaim, S. Efficacy of Chaetomium species as biological control agents against Phytophthora nicotianae root rot in citrus. Mycobiology 43, 288–296 (2015).

Cui, R. et al. The response of sugar beet rhizosphere micro-ecological environment to continuous cropping. Front. Microbiol. 13, 956785 (2022).

Cen, R. et al. Effect mechanism of biochar application on soil structure and organic matter in semi-arid areas. J. Environ. Manag. 286, 112198 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Effect of crop straw biochars on the remediation of Cd-contaminated farmland soil by hyperaccumulator Bidens pilosa L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 219, 112332 (2021).

Chang, T., Salvucci, A., Crous, P. W. & Stergiopoulos, I. Comparative genomics of the sigatoka disease complex on banana suggests a link between parallel evolutionary changes in Pseudocercospora fijiensis and pseudocercospora eumusae and increased virulence on the banana host. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005904 (2016).

Duan, C. et al. Rhizobium Inoculation enhances the resistance of alfalfa and microbial characteristics in copper-contaminated soil. Front. Microbiol. 12, 781831 (2021).

Baazeem, A. et al. Vitro antibacterial, antifungal, nematocidal and growth promoting activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and its secondary metabolites. J. Fungi (Basel) 7, 331 (2021).

Sinsabaugh, R. L. et al. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol. Lett. 11, 1252–1264 (2008).

Yu, Z. et al. Soil bacterial community shifts are driven by soil nutrient availability along a teak plantation chronosequence in tropical forests in China. Biology (Basel) 10, 1329 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Rhizosphere microbial community diversity and function analysis of cut chrysanthemum during continuous monocropping. Front. Microbiol. 13, 801546 (2022).

Ruan, Y. Sucrose metabolism: Gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 65, 33–67 (2014).

Bhaduri, D., Saha, A., Desai, D. & Meena, H. N. Restoration of carbon and microbial activity in salt-induced soil by application of peanut shell biochar during short-term incubation study. Chemosphere 148, 86–98 (2016).

Chodak, M., Sroka, K. & Pietrzykowski, M. Activity of phosphatases and microbial phosphorus under various tree species growing on reclaimed technosols. Geoderma 401, 115320 (2021).

Zhan, Y., Yan, N., Miao, X., Li, Q. & Chen, C. Different responses of soil environmental factors, soil bacterial community, and root performance to reductive soil disinfestation and soil fumigant chloropicrin. Front. Microbiol. 12, 796191 (2021).

Du, L. et al. Comparative characterization of nucleotides, nucleosides and nucleobases in Abelmoschus manihot roots, stems, leaves and flowers during different growth periods by UPLC-TQ-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1006, 130–137 (2015).

Lu, J. et al. Fermentation characteristics of Mortierella alpina in response to different nitrogen sources. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 164, 979–990 (2011).

Igamberdiev, A. U. & Eprintsev, A. T. Organic acids: The pools of fixed carbon involved in redox regulation and energy balance in higher plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 1042 (2016).

Mi, Y. et al. Enhanced antifungal and antioxidant activities of new chitosan derivatives modified with Schiff base bearing benzenoid/heterocyclic moieties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 208, 586–595 (2022).

Hosseyni Moghaddam, M. S., Safaie, N., Soltani, J. & Pasdaran, A. Endophytic association of bioactive and halotolerant Humicola fuscoatra with halophytic plants, and its capability of producing anthraquinone and anthranol derivatives. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 113, 279–291 (2020).

Stursová, M., Zifčáková, L., Leigh, M. B., Burgess, R. & Baldrian, P. Cellulose utilization in forest litter and soil: Identification of bacterial and fungal decomposers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80, 735–746 (2012).

Badawi, N. et al. Metabolites of the phenylurea herbicides chlorotoluron, diuron, isoproturon and linuron produced by the soil fungus Mortierella Sp. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2806–2812 (2009).

Chinese Pharmacopoeia China Pharmacopoeia Commission. China Pharmacopoeia Committee (China Medico-Pharmaceutical Science & Technology Publishing House, 2020).

Wang, H. et al. Effects of different application rates of maize straw on the yield of ginseng in farmland soil. Ren. Shen Yan Jiu 31, 35–36 (2019).

Yin, M., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, L. Effects of different soil improvement treatment on total saponins content in stem and leaf of Panax ginseng cultivated in farmland soil. Hu Bei Nong Ye Ke Xue. 51, 4302–4307 (2015).

Jiao, X. et al. Effects of maize rotation on the physicochemical properties and microbial communities of American ginseng cultivated soil. Sci. Rep. 9, 8615 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. Alkylamide profiling of pericarps coupled with chemometric analysis to distinguish prickly ash pericarps. Foods 10, 866 (2021).

Guan, S. Y., Zhang, D. & Zhang, Z. Soil Enzyme and Its Research Methods (China Agriculture, 1986).

Kolde, R. & Kolde MR. package‘pheatmap’. Rpackage 1 (2015).

Warnes, G. R. et al. gmodels: Various R Programming Tools for Model Fitting (2022).

Wei, T., Simko, V. & Levy, M. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician. 56, e24 (2017).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. WIREs Computational Stats 3, 180–185 (2011).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 20, 241–248 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “Fundamental Research Funds for the Central public welfare research institutes” (ZZ15-YQ-031, ZXKT21033), and the “Scientific and technological innovation project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences” (CI2021A04505). The authors express their great thanks to the editorial staff and reviewers for their time and attention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. L: Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Writing-original draft. Y. C: Investigation. G.Z: Investigation. Yanguo. C: Resources. N. Zhang: Resources. D. Y: Writing-review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition. X. L: Writing-review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Chen, Y., Zhao, G. et al. Herbal materials used as soil amendments alleviate root rot of Panax ginseng. Sci Rep 14, 23825 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74304-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74304-9