Abstract

We present a new seismotomography investigation providing a 3-D overall model of Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs for Mt. Etna, the largest and most active volcano in Europe. We estimated and jointly evaluated P- and S-wave velocity patterns together with the Vp/Vs ratio, particularly useful to discriminate the presence of groundwater, gas, and melts and thus very precious for volcano investigations. We applied the LOTOS software to ~ 4600 crustal earthquakes that occurred in the Etnean area during the last 26 years, the longest time-interval ever analysed for Mt. Etna. This wide dataset has allowed us to characterize the volcano velocity structure getting over possible singularities due to specific eruptive phases. Our results further refined the high velocity body widely recognized in the south-eastern sector of Mt. Etna by furnishing new clues on the possible former magma pathways. Moreover, the obtained 3D seismic velocity model depicted new anomalies revealing the presence of: (i) two shallow underground aquifers in the northern Etnean sector; (ii) a volume of strongly fractured rocks filled of fluids along the eastern flank; (iii) a quite deep region of probable fluid accumulation apparently not linked to the volcanic activity in the western sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seismic tomography based on arrival times of the P- and S-waves from local earthquakes is a powerful tool actively used for studying volcanic systems. For several volcanoes around the world, tomography allowed to successfully reconstruct the shallow-depth volcanic structure (see e.g., Refs.1,2,3,4). Tomographic analyses have furnished, in particular, accurate pictures of the feeding systems and very precious constraints for modelling the volcanic processes also highlighting that each volcano has some peculiar features that makes it unique. In the last decades, tomographic studies have strongly benefited from the strengthening of seismic networks and computational progresses that, particularly for volcanic regions, allowed to carefully reconstruct 3D velocity models by furnishing P- and S-wave velocities and the Vp/Vs ratio, a key parameter to discriminate the presence of groundwater, gas, and melts (Refs.5,6,7, among others). On these grounds, in the present study we collected data from more than 4600 earthquakes recorded between 1997 and 2022 in order to perform a new tomographic inversion of Mt. Etna (South Italy) by applying the software LOTOS8.

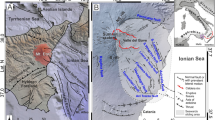

Mt. Etna is the largest and most active volcano in Europe9. It is a composite strato-volcano rising 3300 m above the sea level in eastern Sicily (Fig. 1). Mt. Etna is located at the intersection between several major structural units, where the Apennine–Maghrebian thrust belt, the Hyblean Plateau of the Africa foreland and extensional structures on the western side of the Ionian basin coexist (Fig. 1). Its activity primarily consists of nearly continuous degassing from summit craters, strombolian phases of highly variable intensity, and frequent basaltic lava flows, representing a main source of volcanic hazard in the area. Moreover, flank eruptions during which the magma bypasses the central plumbing system, intrudes as dikes and erupts along the volcano flanks, periodically occur. This kind of event produces a massive deformation affecting the entire morphology of the edifice (e.g., Refs.10,11,12). In particular, in the last decade it has experienced a significant increase in eruption frequency together with the development of some of the most energetic paroxysmal sequences recorded at Mt. Etna in recent times13. These include the three-year-long sequence of lava fountaining occurred between 2011 and 201314 and the very recent sequence of eruptions that took place between December 2020 and February 202215. Moreover, also during the writing of this paper, some episodes of explosions with ash emissions were recorded.

(a) Simplified structural map of Mt. Etna. The main geological structures are labeled: PFS = Pernicana Fault System; TFS = Timpe Fault System; TTFS = Trecastagni - Tremestieri Fault System; ASAF = Acireale – S. Alfio Fault System; SGAF = S. Gregorio – Acitrezza Fault. CC stands for Central Craters. The traces of Alcantara and Simeto rivers are shown as blue curves. Iso-elevation lines with 200 m spacing are also reported. In the bottom left inset is reported a simplified tectonic map of the Calabrian Arc region, redrawn with modifications from Neri et al.16. The solid curve indicates the present-day location of the Ionian subducting system, the sawtooth pattern points in the direction of subduction. Black sawteeth are associated to the in-depth continuous slab, while white sawteeth are related to the slab detachment domain17,18,19. The white arrow shows the sense of the subducting slab rollback. The black arrows indicate the Africa-Europe convergence in the study area according to Nocquet20. Gray belt and converging arrows in the southern Tyrrhenian sea mark the present-day location of the accommodation of the Africa-Europe convergence. “A-M” stands for Apennine-Maghrebian thrust belt (b) Sketch view of the main results coming from previous seismic velocity tomographies for the Etnean region (see text for details). HVp and LVp stand for high P-wave velocity and low P-wave velocity, respectively. The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

In this area several tomographic investigations have been performed by using different input data, grid resolutions and inversion techniques (e.g., Refs.1,10,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28). Referring especially to seismic velocity tomographies, while the P-wave velocity distribution has been extensively investigated, lower attention has been paid in previous studies to S-wave velocity and Vp/Vs ratio. Concerning the latter, most of the available studies have been mainly focused on specific phases of volcanic activity aiming to highlight temporal changes in the Vp/Vs patterns rather than to reconstruct the overall 3D model (e.g., Refs.1,29,30,31). This is why we addressed our tomographic investigation just to reconstruct an all-embracing “phase-independent” 3-D velocity model for the Mt. Etna region that (i) provides P- and S-wave velocity distributions together with the Vp/Vs pattern and (ii) it is derived by a 26 year-long period of data (i.e., the widest time-interval analyzed to date) largely enclosing several volcanic phases. By jointly evaluating Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs distributions, we can furnish a comprehensive picture of the main structural features of Mt. Etna. By using a so long dataset we aim to better characterize the 3D seismic velocity models and the related features untying our investigation from specific volcanic phases (i.e., “phase-independent” model), thus furnishing new contributions to the current research on the internal structure of Mt. Etna.

Previous knowledge on Mt. Etna volcanic system from seismic velocity analyses

Since the second half of the past century, many investigations have been carried out in the Etnean area. The pioneering studies were addressed principally to investigate the deepest portion of the Mt. Etna plumbing system, searching for the possible existence of magma reservoirs. With this regard, Machado32 hypothesized the presence of a very big elliptical magma chamber, with WSW-ENE orientation, located at a depth of about 5 km, and extending from Mt. Etna to approximately the Messina Strait. Afterwards, Sharp et al.21, by analysing travel time residuals, found beneath the volcano a NNE elongated ellipsoidal body characterized by P-wave low velocities at the depth of about 20 km, roughly consistent with the results obtained by Machado32. However, on the basis of their results, Sharp et al.21 stated that the discovered anomaly was most representative of the presence of a series of fissures containing melt, rather than of the existence of a completely molten chamber, in the ‘classical’ sense. Few years earlier, Rittmann33 had denied the existence of a single magma chamber beneath Mt. Etna by observing the chemical variations within single lava flows.

In the last ca. 50 years the study of Mt. Etna volcanic structure has been enriched with several tomographies focused on the reconstruction of the seismic wave velocity models. To evaluate the state of art concerning the knowledge of the 3D velocity structure of Mt. Etna, we reported in Table 1 the main information useful to describe the previous tomographic studies. Table 1 clearly shows the evolution of the performed investigations both in terms of data density, temporal extent and inversion method. We may note that P-wave velocity pattern was deeply investigated since 1980 leading to identify some well-defined anomalies widely shared in the literature (see e.g., the high velocity body discussed in the following). Concerning the S-wave velocity and Vp/Vs ratio, the first analyses started about at the beginning of this century, with some preliminary attempts partially limited by the quality and density of S-data (e.g., Refs.10,23,24,25,34). After these studies, the seismic network improvements and the related increase of available data has led to perform analyses of the Vp/Vs model1,30,31 mainly aimed at highlighting temporal changes of the velocity pattern in correspondence with specific phases of volcanic activity, rather than to furnish a 3D model of the overall volcanic structure (Table 1).

In spite of the different methods, datasets and resolutions, a prominent and commonly inferred feature highlighted by previous investigations is represented by the large high-Vp body located under the central sector of the volcano in the upper 10 km b.s.l., approximately (Fig. 1b; see e.g., Refs.1,10,22,23,24, among others), and usually interpreted as an old magmatic body now completely solidified. Cardaci et al.22 and Scarpa35 reconstructed the high Vp body until 4 km depth (b.s.l.), just close to a gravimetric high36. Villaseñor et al.23 clearly showed the superposition of the volcanic high Vp intrusion on the pre-existing upper crustal structure, highlighting that the crystalline basement is characterized by a rapid velocity increase below about 12 km depth. Aloisi et al.10 further refined the geometry of the high Vp-body and pointed out that the low level of seismicity that characterizes it well correlates with its interpretation as a solidified magmatic body. Laigle et al.25 hypothesized the existence of zones containing portion of melt or fractured inside the high-Vp body and Chiarabba et al.24 proposed that magma ascends the crust within relatively small conduits (Fig. 1b) and, moreover, that it is stored before eruptions at depth shallower than 9 km within the broad high-velocity region.

In the Etnean region also some low velocity anomalies with different size and location have been proposed by several authors. Low P-wave velocities in volcanic framework are usually attributed to rocks being either chemically or thermally altered due to the transit of magmatic and hydrothermal fluids. At depths lower than 10 km, Cardaci et al.22 identified some low Vp anomalies that they associated to the location of an intricate network of fractures mostly filled with magma crossing the basement rocks. Chiarabba et al.’s24 results clearly show that the high velocity body is surrounded by a ring of low velocity anomalies, from 0 to 9 km depth (Fig. 1b) interpreted as the regional Apenninic structure surrounding and hosting the main intrusive bodies beneath the central-western portion of Mt. Etna. Similarly, Giampiccolo et al.30 observed low Vp anomalies around the central intrusive mesh down to 9–12 km depth. Other circumscribed low velocity areas have been identified, particularly along the western border of the high-velocity body, and interpreted as zones of crustal weakness through which magma may migrate to the surface (e.g., Refs.4,10,23). However, not very large low P-wave velocity anomalies interpretable as big, melted magma chamber were found in the 0–18 km depth range (e.g., Refs.1,4,10,24,30).

Concerning the Vp/Vs ratio, Patanè et al.1 and De Gori et al.31 performed time-repeated tomographies using data of earthquakes that occurred in relatively short time intervals (about 2 years) in order to investigate the 2002–2003 flank eruption1 and the melt accumulation phase started in 201926, respectively (Table 1). Also, Giampiccolo et al.30, although furnishing a synthetic description of the obtained 3D models, have mainly focused their analysis on the transient changes in the Vp and Vp/Vs patterns specifically related to the 2018 intrusive period. They highlighted some low Vp and high Vp/Vs anomalies around the central intrusive mesh suggesting the existence of wide volumes of over-pressured fluids, and shallow low Vp/Vs anomalies suggesting the presence of broad gas-dominated volumes within the upper portion of the body.

Data and methods

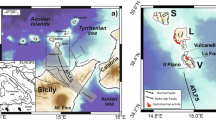

To perform the tomographic inversion, we applied the LOTOS algorithm8 to the local seismicity recorded at permanent and temporary stations managed by Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (www.ingv.it; Fig. 2a). We collected arrival times from earthquakes that have occurred in the Etnean region between January 1997 and December 2022 in the depth range 0–25 km, without selection in magnitude, and having a total number of P and S picks per event larger or equal 12. The obtained dataset consisted of 4630 crustal earthquakes (Fig. 2b). Following a selection procedure already successfully applied in previous studies (e.g., Refs.7,37,38), after locating the sources in a 1D starting model35, we excluded earthquakes with travel-time residuals greater than 1.5s and 2s for P and S readings, respectively. Therefore, for the tomographic inversion 4304 events have been used having on average 15 P- and 8 S-wave picks (70% of events present more than 16 readings). The dataset corresponds to a total of 63,711 P and 35,263 S arrival times, and the related ray tracing distribution ensures that the volume of our interest (dashed box in Fig. 2b) is well sampled by the seismic rays both for P- and S-data. To better frame our tomographic investigation in the context defined by the previous ones, we report in Table 1 the main features of our dataset and inversion settings.

(a) Map of the seismic stations used in the present study (red triangles). The black box encloses the tomographic inversion area. (b) Enlarged view of the inversion region. The epicentral distribution of the starting inversion earthquake dataset is shown. Earthquakes are reported with different symbols and colours according to their magnitude (see legend). The dashed black line encloses the area with the highest tomographic resolution, corresponding to the maps of Figs. 3 and 4, and 5. The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

By using the LOTOS algorithm8, the inversion procedure starts with preliminary source locations based on the grid search method with the use of travel times computed in a 1D starting velocity model. Different 1D velocity models22,23,24,35,39 have been tested to find the most suitable one, i.e. the model that furnishes the highest number of relocated events and the maximum number of used readings by also providing the minimum arrival-time rms. Source locations in the 3D velocity model use 3D ray tracer based on the bending method, which ensures fast stable calculations of travel times of seismic rays between any two points in the study volume. Station corrections are also estimated during the inversion procedure. Velocity parameterization is performed using nodes distributed within the study area according to the ray coverage. In this study, the volume was sampled with a regular horizontal step of 2 km and vertical grid spacing, that is dependent on data density, not smaller than 2 km. To reduce the effect of the grid geometry on the results, we performed the inversions by using grids with four different orientations (i.e., 0°, 22°, 45°and 67°). The models computed for these grids were averaged in a regular mesh used as an updated 3D velocity model in the next iterations8. By following the approach suggested by Koulakov8, we tested different settings of damping and smoothing in order to define the optimal inversion parameters (Figs. S1 and S2). The total number of iterations performed in our study was five. At this stage, the reduction of the average residuals for both P- and S-wave were small enough (i.e., < 1%) to consider the computation stable and the results well constrained. At the end of the process, we obtained the 3D distributions of P- and S-wave velocity patterns, and the Vp/Vs ratio was then computed by dividing the obtained values of Vp and Vs. The final average residuals for P and S data were 0.20s and 0.29s, respectively, corresponding to a reduction of ∼35% and ∼34% with respect to the starting dataset. The final station corrections are very low (about less than 0.005s for P- and S-wave), thus indicating that the tomographic results well reproduce the local velocity structure. The obtained Vp and Vs patterns are reported as percentage variation with respect to the 1D starting model (Figs. 3 and 4) and as absolute values (Fig. S3). The Vp/Vs ratio is shown in Fig. 5.

P-wave velocity model obtained in the present study reported in terms of percentage variation with respect to the optimal 1D reference model. In each map, the number in the low-left corner indicates the b.s.l. depth in km. Color scale has been saturated at + 15%. The white curves enclose the area of percentage variation ≥ + 15%. Dashed ellipses mark the anomalies identified on the basis of the Vp/Vs pattern shown in Fig. 5 and discussed in the text. Iso-elevation lines with 500 m spacing are reported. Black lines are the main faults lying in the area (see Fig. 1 and the related caption for further details). Four vertical sections are also shown (see the profiles in the upper-left map). Pins mark the intersection points between the four profiles. The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

S-wave velocity model obtained in the present study reported in terms of percentage variation of S-wave velocities with respect to the optimal 1D reference model. In each map, the number in the low-left corner indicates the b.s.l. depth in km. Color scale has been saturated at + 15%. The white curves enclose the area of percentage variation ≥ + 15%. Dashed ellipses mark the anomalies identified on the basis of the Vp/Vs pattern shown in Fig. 5 and discussed in the text. Iso-elevation lines with 500 m spacing are reported. Black lines are the main faults lying in the area (see Fig. 1 and the related caption for further details). Four vertical sections are also shown (see the profiles in the upper-left map). Pins mark the intersection points between the four profiles. The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

Maps of the tomographic model obtained in the present study reported in terms of Vp/Vs ratio. In each map, the number in the low-left corner indicates the b.s.l. depth in kmIso-elevation lines with 500 m spacing are reported. Red lines are the main faults lying in the area (see Fig. 1 and the related caption for further details). The labeled ellipses mark the high Vp/Vs anomalies identified in the present study and discussed in the text. Four vertical sections are also shown (see the profiles in the upper-left map). Pins mark the intersection points between the four profiles. The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

In order to carefully evaluate resolution and reliability of the obtained results, we performed a series of synthetic tests whose detailed description and results are reported in the Supplemental Material. In particular, we carried out an odd/even test (Fig. S4) performed running inversions by using subsets of the real dataset used for our investigation. The obtained velocity patterns appear very similar to those retrieved in the main inversion, indicating the robustness of the results obtained with the whole dataset. We also performed a standard checkerboard test by introducing periodic positive and negative velocity anomalies with amplitudes of ± 10% with respect to the 1D starting model and anomaly size of 4 km (Fig. S5), being comparable to the dimension of the anomalies detected in the present study. P and S anomalies appear robustly reconstructed in most parts of the study area in the investigated depth range (Fig. S5), highlighting the good quality and resolution of the obtained results.

In addition, spike tests aimed at reproducing anomalies fairly comparable with those detected by the tomographic inversion have also been performed by constructing different synthetic models (see Figs. S6 and S7 in the supplementary material). The results of these tests point out that the modelled anomalies of Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs were properly retrieved along both the horizontal and vertical directions, indicating a good capability to correctly depict the velocity structure.

Therefore, the results of all the performed tests show that the inversion parameters, which were identical for real and synthetic data inversions, provide optimal quality reconstructions and that the above discussed anomalies are located in well resolved areas, therefore they can be considered as reliable observations and not artefacts introduced by the inversion process.

Results and discussions

We computed a complete “phase-independent” 3D velocity model for the Etnean region providing Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs distributions (Figs. 3 and 4, and 5). The overall velocity patterns obtained in this work allowed us both to refine the main features described in previous papers and to identify new previously undetected anomalies, mainly depicted starting from by evaluating the Vp/Vs distribution.

Refining of previous findings

Concerning the main velocity anomaly already discussed in the literature and summarized in a previous section, the high P-wave velocity body located in the southeastern sector of Mt. Etna is clearly shown at all investigated depths (0–10 km, Fig. 3). Our results highlight that (i) the high Vp anomaly is characterized by a low level of seismic activity, (ii) it is also associated to a high Vs pattern and therefore, to a relatively low Vp/Vs ratio, and (iii) it appears visibly elongated in-depth toward S-SE along the flank of the volcano. These features further support the widely shared interpretation of this high velocity anomaly as an old magmatic body now completely cooled (e.g., Refs.10,22,40). Referring to the possible presence of melted material and/or feeding conduits in this volume, our results furnished particularly high Vs values (∆Vs ≥ 15%) with consequent low Vp/Vs (ca. 1.60, on average), thus we tend to exclude the possible presence of a big magma chamber or wide feeding conduits filled with magmatic fluids. Therefore, in this sector melted materials, when present, should occupy quite small volumes (i.e., not large enough to be resolved by this tomographic investigation). This feature is plausible and expected, somehow confirming the geological observations on the narrowness (meter scale) of the adducting conduits at the main craters (see e.g., Ref.41 and references therein). Moreover, it is also compatible with the previous hypothesis of the existence of networks of “abyssal fissures” or melt-filled fractures (see e.g., Refs.25,33) and it is in perfect agreement with the absence of differentiated members in the Etnean products, both recent and historical42.

We also note that the well depicted in-depth elongation of the high Vp body towards S-SE (see Fig. 3), not yet highlighted by previous studies, may indicate that the deep region from which the magma migrated toward the surface in the past was probably located south-east of the volcano edifice. At the southeastern flank of Mt. Etna lies a well-developed tectonic system that several authors considered as the on-shore prolongation of major structural discontinuities located in the Ionian off-shore (i.e., the Malta escarpment and the Alfeo-Etna fault system, Fig. 1; Refs.23,43,44). Moreover, along this major tectonic alignment, crustal structures such as releasing bends, pull-apart basins and extensional horsetails have been observed both offshore and on-land, where they probably represented the pathway for magma uprising from depth44. On this regard, Neri et al.45, by simulating crustal magma pathways beneath eastern Sicily have found non-vertical tracks confirming that the Etnean volcanism has been fed laterally from the eastern sector, as proven by the remains of the volcanic eruptive centres, presently located in the Ionian off-shore. Thus, our reconstruction of the deep geometry of the high Vp body seems to further supports this hypothesis.

In addition, we notice the presence of a quite small and not so pronounced anomaly of relatively increased Vp/Vs located inside the high-velocity body, at a depth of 2–3 km below the central crater and characterized by intense seismicity (see section BB’ in Fig. 5). As said above, no large magma storages are expected at shallow depths beneath Mt. Etna, and the magma transport may occur from large depths through a system of fractures, which should not be revealed as prominent seismic velocity anomalies. In this framework, this anomaly of relatively high Vp/Vs beneath the central craters area could deserve further investigations, being possible evidence of how the effect of fracturing might significantly change the integral velocity below the summit.

Finally, the obtained P-wave velocity model shows diffused areas of low Vp around the main high Vp body (Fig. 3 and S3), as already observed by previous authors (see Refs.22,24,30, among others). In correspondence with the low Vp zones, our results mainly show low values of Vs (Fig. 4), low-to-average Vp/Vs (Fig. 5), and moderate seismic activity, signatures compatible with regions of crustal weakness4,10,23.

New inferences from the joint evaluation of the Vp, Vs, and Vp/Vs patterns

It is well known that seismic velocities mainly depend on several parameters like rock fabric, temperature, pressure, fluid content, porosity or crack shape and distribution, and that they are able to provide relevant information about the structural features of volcano feeding systems. As the Vp/Vs ratio distribution is often considered one of the most informative parameters in volcanic investigations, since, at crustal level, it appears highly sensitive to the content of gases, fluids and melts within the rocks, we use the Vp/Vs pattern (Fig. 5) as guideline to discuss the following new results. In a general frame of low-to-medium Vp/Vs values, we highlight the presence of circumscribed well-constrained high Vp/Vs anomalies.

At the shallowest layer (i.e., 0 km), it is noteworthy the presence of two well depicted zones of high Vp/Vs in the northern sector of Mt. Etna (1a and 1b in Fig. 5). These anomalies, never found in previous tomographies, are due to low-to-average Vp and very low Vs values and show small extension both horizontally and vertically (Figs. 3 and 4). Since the obtained Vp values can be associated to the existence of volcanic rocks and very low Vs may be due to the presence of considerable amounts of fluids, the two small shallow anomalies (1a and 1b in Fig. 5) might be associated with underground aquifers caused by meteoric water penetrating into the volcano edifice. Similar velocity patterns are very typical features in volcanic regions commonly interpreted as zones of consolidated but highly permeable magmatic rocks composing the volcanic edifices and highly saturated with meteoric fluids5,46,47,48,49,50. This interpretation well agrees with resistivity and magnetotelluric analyses performed in the Etnean region51,52. These authors identified, in close correspondence to the easternmost high Vp/Vs anomaly (1b in Fig. 5), a low resistivity area reflecting the presence of a highly fractured zone (see e.g., the Pernicana Fault, PFS in Fig. 1a) where meteoric fluids easily infiltrate the ground until they reaching the hydrothermal reservoir51. Also, the sector where the western high Vp/Vs anomaly lies (1a in Fig. 5) appears to be characterized by resistivity values comparable to those observed to the East52. Moreover, its limited extension in depth (as anomaly 1b) and the similarity with anomaly 1b also concerning the velocity and resistivity patterns led us to hypothesize the presence of meteoric fluid circulations in this volume too. This interpretation finds a confirmation in the corresponding presence of many springs feeding the two main rivers of the region located at the foot of Mt. Etna, in the north-western and in the north-eastern side, respectively (Simeto and Alcantara rivers, Fig. 1a).

A high Vp/Vs anomaly (2 in Fig. 5), produced by moderately high Vp and low Vs variations (Figs. 3 and 4), is clearly detectable in the 0–10 km depth interval along the eastern flank of Mt. Etna, in a sector characterized by intense seismicity and several fault systems (Fig. 1a). Siniscalchi et al.52 found in the same area (Timpe, TFS in Fig. 1a) a drastic flexure of the intermediate conductive layer pointing downward and eastward (from 3 to 10 km bsl). The same authors observed that this feature is located close to a possible low-density body already observed in a 3D gravimetric investigation of the Etnean area53, and interpreted it as a volume of intensely fractured sedimentary rocks, whose surface expression coincides with the area of intersection of several fault segments (Fig. 5). The presence of a fluids could be held responsible for the observed velocity patterns: Vs would be strongly reduced due to the presence of fluid-filled cracks, while Vp does not significantly change being minimally affected by the presence of fluids (see also Ref.54). Considering that P- and S-wave velocities vary significantly as a function of rock saturation and lithostatic pressure, we remark that in fluid-saturated rocks at low effective pressure (i.e. upper crustal depths), cracks are open, and fluids can circulate within a well-developed system of fractures thus determining the observed high Vp/Vs values (Ref.55, and references therein). According to several authors46,47,56, meteoric water may not propagate at depths comparable with those of the observed high Vp/Vs anomaly (ca. 10 km). We therefore suggest that the obtained velocity pattern may reflect the rise of large quantity of fluids through the deeply dissected upper crust; this is also in good agreement with the presence in this sector of Mt. Etna of natural thermal springs mainly related to deep sources54,57,58.

In the western side of the study region, in the 6–10 km depth range, a high Vp/Vs zone associated with moderately low Vp and low Vs is detectable (anomaly 3 in Figs. 3 and 4, and 5). This volume is characterized by very low seismic activity with earthquakes mainly located at its south-eastern boundary. Signatures similar to this anomaly have been interpreted, in other volcanic regions, as an indication for sedimentary rocks modified by the presence of fluids (Ref.59, and references therein). As a matter of fact, the existence of this high Vp/Vs zone below 6 km, on the western flank of Mt. Etna, does not seem to find any direct correlation with the volcanic activity. It is possible to infer that, at such depth, discontinuities within the geological succession of the sedimentary Etnean basement, which has undergone orogenic compression and isostasy, could allow the rise and likely the accumulation of fluids not necessarily associated to the volcanic activity.

Conclusions

The 3D seismic velocity patterns obtained through our tomographic inversion has allowed us to add further details on already known anomalies and to identify new previously undetected ones.

Concerning the former, our results highlighted that the high P-wave velocity body previously identified by several authors beneath the south-eastern sector of Mt. Etna is characterized by high Vs and relatively low Vp/Vs and is visibly elongated in-depth toward S-SE along the flank of the volcano. The Vs and Vp/Vs patterns seem to exclude the possible presence of a big magma chamber or of wide feeding conduits filled with magmatic fluids in this area, leading to hypothesize that melted materials, when present, should occupy quite small volumes. The existence of high velocity below a basaltic volcano like Mt. Etna is a quite typical feature. Moreover, such a consolidated medium behaves in a brittle way and is favourable for forming fractures enabling fast transport of low-viscosity basaltic materials from large depths60. Furthermore, the observed S-SE in-depth elongation (Fig. 6) suggests that the deep region from which the former magma migrated toward the surface was located south-southeast of the volcano edifice where the well-developed tectonic system of the Malta-Escarpment is located. The red dotted line in Fig. 6 schematically represents the possible system of fractures within the rigid body served as magma conduits.

Sketch view of the main results obtained in the present study reporting: (i) the SSE elongated high P-wave velocity body (wide blue area in figure); (ii) the location of the shallow aquifers detected on the northern side of Mt. Etna (i.e., the two small light-blue anomalies at very shallow depths); (iii) the high Vp/Vs anomaly identified on the eastern flank of the volcano (wide red-to-green area on the right); (iv) the high Vp/Vs region between 6 and 10 km on the western side of Mt. Etna (small red-to-green area on the left). For each feature, the corresponding Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs patterns are reported. The red dashed line in the high velocity body indicate the possible former pathway for magma uprising (see text for further details). The Figure has been managed by using the softwares QGIS (version 3.10, https://qgis.org/), GMT (version 6, https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022, www.coreldraw.com).

Focusing on the new anomalies, not identified in previous tomographies, at the shallowest layer it is noteworthy the presence of two circumscribed volumes characterized by high Vp/Vs. Their correspondence with low resistivity areas51,52 indicate that these anomalies can be associated to underground aquifers caused by meteoric water penetrating the volcano edifice (Fig. 6).

Moreover, a high Vp/Vs anomaly produced by moderately high Vp and low Vs values and characterized by intense seismicity is clearly detectable along the eastern flank of Mt. Etna, in the 0–10 km depth interval (Fig. 6). It represents a volume of strongly fractured sedimentary rocks, through which a large amount of fluids may rise thus determining low Vs and high Vp/Vs values.

Finally, on the western side of the study region, in the 6–10 km depth range, a high Vp/Vs area associated with moderately low Vp, low Vs and very low seismic activity is detectable (Fig. 6). The velocity patterns suggest an accumulation of fluids, probably not associated to the volcanic activity, even if further investigations are necessary to better solve and understand this previously unknown anomalous region.

The new insights derived from the tomographic results point out the relevance of exploiting the increase and the quality improvement of both data and techniques in order to furnish continuous updates of the seismic velocity structures, also by means of different approaches and perspectives. In this framework, our results have clearly proven the advantage of providing a comprehensive “phase-independent” 3-D model that encompasses specific volcanic phases and makes also possible to joint interpret Vp, Vs and Vp/Vs patterns, in order to provide a more complete modeling of the main features of Mt. Etna.

Data availability

Earthquake data are available on the INGV institutional website (http://www.ingv.it). The LOTOS code can be downloaded from http://www.ivan-art.com/science/LOTOS. Figures reported in this paper have been managed by using the sofwares QGIS (version 3.10), GMT (version 6), and CorelDraw (Technical Suite 2022). Data not available on these websites can be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Patanè, D., Barberi, G., Cocina, O., De Gori, P. & Chiarabba, C. Time-resolved seismic tomography detects magma intrusions at mount etna. Sci. (1979) 313, 821–823 (2006).

Kiser, E. et al. Magma reservoirs from the upper crust to the Moho inferred from high-resolution vp and vs models beneath Mount St. Helens, Washington State, USA. Geology 44, 411–414 (2016).

Widiyantoro, S. et al. Seismic imaging and petrology explain highly explosive eruptions of Merapi Volcano, Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 8, (2018).

Díaz-Moreno, A. et al. New Insights on Mt. Etna’s Crust and Relationship with the Regional Tectonic Framework from Joint Active and Passive P-Wave Seismic Tomography. Surveys in Geophysics vol. 39 57–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-017-9425-3 (2018).

Kuznetsov, P. Y. et al. Structure of volatile conduits beneath gorely volcano (Kamchatka) revealed by local earthquake tomography. Geosci. (Switzerland) 7, (2017).

Vargas, C. A. et al. Breathing of the Nevado Del Ruiz volcano reservoir, Colombia, inferred from repeated seismic tomography. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

Totaro, C. et al. New insights on the active degassing system of the Lipari–Vulcano complex (South Italy) inferred from local earthquake Tomography. Sci. Rep. 12, (2022).

Koulakov, I. LOTOS code for local earthquake tomographic inversion: Benchmarks for testing tomographic algorithms. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 99, 194–214 (2009).

Chester, D. K., Duncan, A. M., Guest, J. E. & Kilburn, C. R. J. Mount Etna: The Anatomy of a Volcano (Chapman & Hall, 1985).

Aloisi, M., Cocina, O., Neri, G., Orecchio, B. & Privitera, E. Seismic tomography of the Crust underneath the Etna Volcano, Sicily. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 134 (2002).

Aloisi, M. et al. A new dyke intrusion style for the Mount Etna May 2008 eruption modelled through continuous tilt and GPS data. Terra Nova 21, 316–321 (2009).

Palano, M., Pezzo, G. & Chiarabba, C. Magma budget, plutonic growth and lateral spreading at Mt. Etna. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, (2024).

Giuffrida, M., Cardone, M., Zuccarello, F. & Viccaro, M. E. 2011–2022: Discoveries from a decade of activity at the volcano. Earth-Science Reviews vol. 245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104563 (2023).

Giuffrida, M. & Viccaro, M. Three years (2011–2013) of eruptive activity at Mt. Etna: Working modes and timescales of the modern volcano plumbing system from micro-analytical studies of crystals. Earth-Science Reviews vol. 171, 289–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.06.003 (2017).

Calvari, S. et al. Explosive paroxysmal events at Etna Volcano of Different Magnitude and intensity explored through a multidisciplinary monitoring system. Remote Sens. (Basel) 14, (2022).

Neri, G., Orecchio, B., Scolaro, S. & Totaro, C. Major Earthquakes of Southern Calabria, Italy, into the Regional Geodynamic context. Front. Earth Sci. (Lausanne) 8, (2020).

Neri, G., Orecchio, B., Totaro, C., Falcone, G. & Presti, D. Subduction beneath southern Italy close the ending: results from seismic tomography. Seismol. Res. Lett. 80, (2009).

Neri, G. et al. How lithospheric subduction changes along the calabrian Arc in southern Italy: geophysical evidences. Int. J. Earth Sci. 101, (2012).

Orecchio, B., Presti, D., Totaro, C. & Neri, G. What earthquakes say concerning residual subduction and STEP dynamics in the calabrian Arc region, south Italy. Geophys. J. Int. 199, (2014).

Nocquet, J. M. Present-day kinematics of the Mediterranean: A comprehensive overview of GPS results. Tectonophysics vol. 579 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2012.03.037 (2012).

Sharp, A. D. L., Davis, P. M. & Gray, F. ARTICLES a low Velocity Zone beneath Mount Etna and Magma Storage. Nature vol. 287 (1980).

Cardaci, C., Coviello, M., Lombardo, G., Patan6, G. & Scarpa, R. Seismic tomography of Etna Volcano. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 56 (1993).

Villaseñor, A. et al. Three-dimensional P-wave velocity structure of Mt. Etna, Italy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 1975–1978 (1998).

Chiarabba, C., Amato, A., Boschi, E. & Barberi, F. Recent seismicity and tomographic modeling of the Mount Etna plumbing system. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 105, 10923–10938 (2000).

Laigle, M. et al. Mount Etna dense array local earthquake P and S tomography and implications for volcanic plumbing. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 105, 21633–21646 (2000).

Castro-Melgar, I., Prudencio, J., Del Pezzo, E., Giampiccolo, E. & Ibáñez, J. M. Shallow Magma Storage beneath Mt. Etna: evidence from New Attenuation Tomography and existing velocity models. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, (2021).

Magnoni, F. et al. Adjoint tomography of the Italian lithosphere. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, (2022).

Giampiccolo, E., Tuvè, T., Bianco, F. et al. Depth and spatial variation of the shear wave attenuation parameters in the Shallow Crust and Lower Crust/Upper Mantle of Mt. Etna (Italy). Pure Appl. Geophys.181, 171–187 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-023-03400-0.

Alparone, S. et al. Intrusive mechanism of the 2008–2009 Mt. Etna eruption: constraints by tomographic images and stress tensor analysis. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 229–230, 50–63 (2012).

Giampiccolo, E., Cocina, O., De Gori, P. & Chiarabba, C. Dyke intrusion and stress-induced collapse of volcano flanks: the example of the 2018 event at Mt. Etna (Sicily, Italy). Sci. Rep. 10, (2020).

De Gori, P. et al. Re-pressurized magma at Mt. Etna, Italy, may feed eruptions for years. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, (2021).

Machado, F. The messina earthquake of 1908 and the magma chamber of Etna. Bull Volcanol. 28, 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02596939 (1965).

Rittmann, A. & Sato, M. Structure and evolution of Mount Etna. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. 274, 5–16 (1973).

De Luca, G., Filippi, L., Patanè, G., Scarpa, R., & Vinciguerra, S. Three-dimensional velocity structure and seismicity of Mt. Etna Volcano, Italy. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 79 (1997).

Scarpa, R. Geophysical Exploration in Areas of Complex Geology. J. Appl. Geophys. 30 (1993).

Loddo, M. et al. Application of gravity and Deep Dipole Geoelectrics in the volcanic area of Mt. Etna (Sicily). J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 39 (1989).

Totaro, C., Koulakov, I., Orecchio, B. & Presti, D. Detailed crustal structure in the area of the southern Apennines-calabrian Arc border from local earthquake tomography. J. Geodyn. 82, (2014).

Totaro, C. et al. Seismotomographic detection of major structural discontinuity in northern Sicily. Ital. J. Geosci. 136, (2017).

Hirn, A., Nercessian, A., Sapin, M. & Ferrucci, F. & Wittlinger, G. Seismic Heterogeneity of Mt Etna: Structure and Activity. Geophys. 1. Inr vol. 105. https://academic.oup.com/gji/article/105/1/139/667029 (1991).

Cristofolini, R., Lentini, F., Patanè, G. & Rasa, R. Integrazione Di Dati Geologici, geofisici e petrologici per la stesura di un profilo crostale in corrispondenza dell’Etna. Bollettino Della Società Geologica Italiana (1979).

Scudero, S., De Guidi, G. & Gudmundsson, A. Size distributions of fractures, dykes, and eruptions on Etna, Italy: implications for magma-chamber volume and eruption potential. Sci. Rep. 9, (2019).

Ferlito, C. & Lanzafame, G. The role of supercritical fluids in the potassium enrichment of magmas at Mount Etna volcano (Italy). Lithos 119, 642–650 (2010).

Hirn, A., Nicolich, R., Gallart, J., Laigle, M. & Cernobori, L. EPSL Roots of Etna Volcano in faults of Great earthquakes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 148 (1997).

Gambino, S. et al. Transtension at the Northern termination of the Alfeo-Etna Fault System (Western Ionian Sea, Italy): seismotectonic implications and relation with Mt. Etna Volcanism. Geosci. (Switzerland) 12, (2022).

Neri, M., Rivalta, E., Maccaferri, F., Acocella, V. & Cirrincione, R. Etnean and Hyblean volcanism shifted away from the Malta Escarpment by crustal stresses. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 486, 15–22 (2018).

Hurwitz, S. Groundwater flow, heat transport, and water table position within volcanic edifices: implications for volcanic processes in the Cascade Range. J. Geophys. Res. 108, (2003).

Bushenkova, N. et al. Tomographic images of Magma chambers beneath the Avacha and Koryaksky volcanoes in Kamchatka. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 9694–9713 (2019).

Komzeleva, V. et al. Sources of the eruption of Kambalny volcano (Southern Kamchatka) in March 2017 inferred from local earthquake tomography. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 420, (2021).

Koulakov, I. et al. Anatomy of the Bezymianny volcano merely before an explosive eruption on 20.12.2017. Sci. Rep. 11, (2021).

Koulakov, I., Komzeleva, V., Smirnov, S. Z. & Bortnikova, S. B. Magma-Fluid interactions beneath Akutan Volcano in the Aleutian Arc based on the results of local earthquake Tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, (2021).

Siniscalchi, A. et al. Insights into fluid circulation across the Pernicana Fault (Mt. Etna, Italy) and implications for flank instability. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 193, 137–142 (2010).

Siniscalchi, A. et al. Flank instability structure of Mt. Etna inferred by a magnetotelluric survey. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth vol. 117. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008657 (2012).

Schiavone, D. & Loddo, M. 3-D density model of Mt. Etna Volcano (Southern Italy). J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 164, 161–175 (2007).

Nugraha, A. D. et al. Joint 3-D tomographic imaging of vp, vs and Vp/Vs and hypocenter relocation at Sinabung volcano, Indonesia from November to December 2013. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 382, 210–223 (2019).

Valoroso, L., Improta, L., De Gori, P. & Chiarabba, C. Upper crustal structure, seismicity and pore pressure variations in an extensional seismic belt through 3-D and 4-D VP and V P/VS models: the example of the val d’Agri area (southern Italy). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116, (2011).

Ferrara, V. & Pappalardo, G. The hydrogeological map of the etna volcanic massif as useful tool for groundwater resources management. Italian J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 1, 77–89 (2008).

Sortino, F., Giammanco, S., Bonfanti, P. & Bottari, C. Stress-induced changes in hydrothermal gas discharges along active faults near Mt. Etna volcano (Sicily, Italy). Tectonophysics 836, (2022).

Bottari, C., Capizzi, P. & Sortino, F. Unraveling the seismic source in Archaeoseismology: A Combined Approach on Local Site effects and Geochemical Data Integration. Heritage 7, 427–447 (2024).

Muksin, U., Bauer, K. & Haberland, C. Seismic vp and Vp/Vs structure of the geothermal area around tarutung (north sumatra, Indonesia) derived from local earthquake tomography. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 260, 27–42 (2013).

Ferlito, C. Mount Etna volcano (Italy). Just a giant hot spring! Earth-Science Reviews vol. 177 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.004 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions that allowed us to significantlyimprove the article.The Authors acknowledge the support of the APC central fund of the University of Messina.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T. conceived and coordinated the research; performed the tomographic inversion. C.T., S.S., D.P., and B.O. analysed the tomographic results and evaluated their resolution and reliability. M.A. and C. F. framed the results into the geophysical and volcanological feature of the study area. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Totaro, C., Aloisi, M., Ferlito, C. et al. 3D seismic velocity models from local earthquake tomography furnish new insights on the Mount Etna volcano (Southern Italy). Sci Rep 14, 28469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74349-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74349-w