Abstract

While prior research has found that leaders tend not to abuse subordinates equally, empirical studies exploring the differentiation phenomenon of abusive supervision still remain limited. Drawing on relative deprivation theory, the differentiation of abusive supervision is defined as the two operational indicators of relative abusive supervision and abusive supervision variability according to the dual influence this differentiation imposes on both individuals and groups. How the interactive effect of relative abusive supervision and abusive supervision variability impacts employees’ behaviors is examined and the solution to the abusive supervision differentiation dilemma is explored. The results of a two-wave empirical study including 254 employees from 84 groups demonstrate that focal employee relative abusive supervision negatively influences task performance and organizational citizenship behavior via relative deprivation. This effect is amplified when the group has lower levels of abusive supervision variability. This study contributes to a better understanding of abusive supervision in groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s fast-paced business environment, the occurrence of abusive supervision in the workplace has increased1. According to Tepper et al. (2011), about 13% of employees in the USA are abused to varying degrees by their supervisors2. In China, the famous feudal saying of “noblemen hold a higher position than their subjects” still applies between leaders and subordinates, which increases the occurrence of abusive supervision in organizations3. A survey conducted by zhaopin.com involving over ten thousand Chinese workers showed that more than 49% of employees encounter “emotional office abuse” from their leaders.

To date, prior studies on abusive supervision have mainly focused on its harmful effects at the individual level4,5. However, as abusive supervision happens in a social environment6, how the same leader abuses various colleagues will affect the reaction of focal employees7. This finding is consistent with the results of Matta et al. (2015), who showed that how a leader treats a specific focal employee compared to other group members provides a clue about the status of this focal employee in the group8. Thus, the available understanding of how focal employees respond to abusive supervision may be incomplete without also considering the context of colleagues who may or may not be abused.

Recent research has indicated that leaders prefer to be selective in whom to abuse9,10, implying an uneven distribution of abusive leadership. This phenomenon deserves more consideration in groups where the same leader supervises multiple employees. Moreover, the differentiation of abusive supervision for group members must impact the attitudes and behaviors of employees11. Despite the importance of social contexts for the response of focal employees, research exploring the influence of social comparison of abusive supervision on the cognitions, emotions, and behaviors of a focal employee in a group has been limited12.

We propose that relative levels of abusive supervision may impact the perceptions of focal employees, thus affecting the extent to which abusive supervision harms them. In a sense, the social comparison of abusive supervision within a group plays a more critical role for the attitudes and behaviors of focal employees than absolute abuse13. More importantly, this perspective also clarifies why different employees within a team react differently to the same degree of abusive supervision. However, most research on abusive supervision has focused on the impact of the absolute value of abuse supervision on employees, while ignoring the impact of the effect of social comparison under abusive supervision.

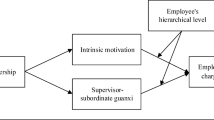

To discuss social comparison under abusive supervision, the two notions of employee relative abusive supervision (RAS) at the individual level, and a dispersion composition conceptualization at the group level called abusive supervision variability (ASV) are proposed. Both can be understood as the embodiment of the social comparison of abusive supervision at different levels of the theory. Although both forms of abusive supervision originate from the same source, they are independent of each other. Relying on these two concepts, a theoretical model is developed that illustrates how the differentiation of abusive supervision in a group influences the attitudes and behaviors of focal employees (see Fig. 1).

Drawing from the relative deprivation theory14, we propose that RAS—i.e., the extent to which a focal employee suffers higher levels of abusive supervision compared with other group members15—positively affects employee perceptions of relative deprivation. We also hypothesize that ASV—i.e., the extent of the dispersion of abusive supervision within a group11—weakens the correlation between RAS and relative deprivation. In addition, relative deprivation theory14argued that the relative deprivation perceived by employees is likely to further influence their subsequent work attitudes and behaviors. Given that job performance is a crucial indicator of individual and organizational effectiveness, the downstream consequences of RAS and ASV on job performance—including task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)16—mediated by focal employee perceptions of relative deprivation are also examined. Job performance serves as a comprehensive measure encompassing an employee’s ability to execute tasks, meet job expectations, and contribute positively to organizational goals. By examining the impact of RAS on task performance and OCB through the lens of relative deprivation, the research provides valuable insights into how the differential abuse of employees by supervisors can influence their actual work outcomes.

This paper contributes to the literature by highlighting the contextual nature of abusive supervision. Firstly, the relative levels of abusive supervision are examined, which creates unique issues that are less apparent and unlikely to be addressed by previous raw score approaches to abusive supervision (e.g., Tepper et al., 2017)17or prior group-level operations that focus on the average abuse score within a group (e.g., the abusive supervision climate)18. Secondly, relative deprivation theory is introduced to explain how leadership behavior can be transformed into subordinate behavior through emotional repercussion; moreover, the mediator of relative deprivation between RAS and job performance is also explored. Although prior research has examined the affective mechanism of abusive supervision (e.g., negative affect)19, studies that consider the role of the discrete emotional response to RAS are relatively limited10. Thirdly, employees are always nested within a group, and both the work performance and behavior of the individual employee are primarily rooted in the background of the group20. Initial evidence is provided in support of the cross-level interaction effect between RAS and ASV, thus enriching the literature on the contextualization effect of abusive supervision.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Relative deprivation theory

Festinger (1954) argued that people often use social comparison to recognize their own status and abilities21. Stouffer (1949) put forward the construct of relative deprivation from social comparison22. More recently, Smith et al. (2012) systematically interpreted relative deprivation theory, showing that by comparing the self with the reference object, individuals infer the superiority or inferiority of their status, which may produce a sense of relative deprivation14. Relative deprivation originates from social comparison—a common phenomenon that is deeply embedded in the organizational structure23. Therefore, when focal employees compare themselves with other group members and think that they are at a disadvantage in the work unit within an organization, they will form a sense of relative deprivation.

As a kind of continuous destructive leadership style, abusive supervision often causes tension between group leaders and employees and leads subordinates to think that leaders do not attach enough importance to them. Such leaders tend to trigger the social comparison process in group members who suffer abuse to get to know their RAS within the group, judge their relative status, and decide whether to generate relative deprivation24, which affects their job attitudes and behaviors25.

Relative abusive supervision and relative deprivation

RAS refers to the individual level phenomenon that emerges while group members try to judge their relative position in the team via comparison with peers; specifically, RAS refers to the extent of difference between the perceived abusive supervision of focal employees compared with the mean abusive supervision directed toward all other members of the group15. Only by choosing the mean value of group abuse as the reference point can the relative position of individual abuse in the group be reflected; if one or a few colleagues in the group are selected for comparison, such information cannot be obtained26. In addition, social comparative theorists have also found that individuals prefer to pick the “mean” or the whole group as a reference object27.

While both RAS and abusive supervision originate from the same organizational phenomenon, certain differences are apparent: first, the connotation differs. Abusive supervision refers to the absolute value of abuse perceived by subordinates, which excludes group situations and isolated consideration; RAS refers to the relative value of abusive supervision after group members put exposed abuse into group situations for social comparison. Second, theory levels differ. Abusive supervision is at the individual level of the theory, while RAS is at the individual-within-group level of the theory.

Employees not only perceive the absolute value of the abuse their leaders direct toward them but also perceive the relative value of abuse by comparison with other group members. This serves as the basis for a series of outcomes such as perceived leadership support, job satisfaction, and status in the group28. Relative deprivation theory suggests that when an individual compares the current environment to a specific reference or a certain psychological standard, once that individual perceives to be at a disadvantage, he/she will feel deprived29. Based on this logic, when focal employees compare themselves with other members of the group, they find that their RAS is higher; then, they will feel that they are at a relative disadvantage in the group and perceive a lower social status compared to other group members, resulting in feelings of relative deprivation30. Moreover, the larger the discrepancy, the more likely it is to lead to the emergence of negative emotions31. Thus, we infer that there is a positive relationship between RAS and relative deprivation.

Hypothesis 1

RAS is positively associated with relative deprivation.

The moderating role of abusive supervision variability

Social comparison of abusive supervision is also reflected at the group level. In this study, ASV is used to reflect the different contextual effects that occur when a leader directs different levels of abuse toward employees who belong to the same group; ASV refers to the dispersion of abusive supervision within a group11. It represents a process in which leaders adopt different modes of abuse for different employees, ultimately forming differentiated contexts and showing group characteristics. Specifically, abuse disperses in high abuse supervision variability groups, while in low abuse supervision variability groups, abuse converges.

The moderation effect of ASV can be further recognized by the “frog-pond effect,” an idea derived from a social comparative perspective32. The “frog-pond effect” refers to the idea that when placed into a large pond, a large frog appears to be smaller than when placed into a small pond. Salancik & Pfeffer (1978) suggested that various items of information in the work context provide clues for employees to construct and interpret a particular work event, thus affecting both their cognition and attitude33. Research on the “frog pond effect” showed that the significance of the behaviors of organizational members to others depends on the universality or rarity of these specific behaviors within the social background34. ASV provides individuals with “differentiated” background information, which may inadvertently become an external source of information that affects their further judgment and perception35. Moreover, the differentiated context inevitably triggers the social comparison process among members, leading to the formation of RAS, which reflects the relative position of a specific individual within the group. If the level of abusive supervision variability is high, leaders treat their members differently, thus creating a differentiated atmosphere, which impacts the group members’ perception of abusive supervision. In turn, these perceptions serve as a lens through which focal employees explain abusive behavior. Therefore, it can be inferred that under different levels of ASV, the behavior of focal employees with high levels of RAS may vary.

As an illustration, focal employees in a group compare the degree of abuse they are subjected to with the degree others are subjected to and thus obtain RAS. Subsequently, they will compare relative values horizontally within the team and gauge the differences in leaders’ treatment of different members; in turn, they will judge the particularity of the abuse they suffered and their position within the team. Consistent with prior research, we reason that the distribution of abusive supervision varies across different groups9,36; for instance, while certain leaders abuse all employees equally, others treat different employees in a more differentiated way. This phenomenon (i.e., differentiation in abusive supervision) potentially impacts the influencing mechanism of an individual’s relative abuse. As a team contextual variable, this can provide critical external information and even criteria for individuals’ cognition, comparison, and judgment, thus influencing the role of RAS35.

Specifically, the same level of RAS will be more prominent in groups with low ASV; namely, the effect of RAS will be “amplified” under low levels of ASV. In this case, the individual may perceive stronger dissatisfaction and prejudice from the leader, and thus, the sense of deprivation caused by high levels of relative abuse will be enhanced. On the contrary, when leaders subject their employees to differentiated levels of abuse, the difference in relative abuse is slim; thus, the impact on individual perception is relatively weak regardless of the nature of abusive supervision.

To the best of our knowledge, this cross-level moderating effect has not been addressed in the existing literature on abusive supervision. However, a similar effect has been observed in a study by Le & Gonzalez (2012)37, which examined the interaction between leader-member exchange (LMX) and differentiation of LMX at the group level. Additionally, variability in justice has been shown to undermine the benefits typically associated with employees’ perceptions of interpersonal justice38. These findings suggest a broader pattern in which differentiated background information acts as an external source influencing employees’ further judgment and perception. This pattern may also be applicable to variability contexts of abusive supervision, despite differences in the specific constructs of leadership behavior. Moreover, Peng et al. (2014) found that when colleagues are also subjected to abuse, the negative effects of individual abuse are mitigated39, which also implies the moderating effect of ASV. The perception of differentiation in abusive supervision may trigger social comparisons among team members6and foster negative emotions toward peers perceived to have experienced less abuse39. For instance, in contexts with low ASV, employees who perceive relative abusive supervision may feel singled out for abuse or envy others who face relatively less abuse10. These experiences can ultimately lead to feelings of relative deprivation. Therefore, we argue that in groups with low levels of ASV, the effect of focal employees’ RAS on their relative deprivation and behaviors will be magnified.

Hypothesis 2

ASV moderates the direct effect of RAS on relative deprivation, in such a way that the positive effects are stronger when ASV is low, compared to when it is high.

Consequences of relative deprivation

Relative deprivation theory holds that relative deprivation reflects the perception of one’s inferior position after comparison to a reference object40. The perception of this individual’s inferior position will further cause adverse emotional reactions such as discontent and resentment14, thereby affecting attitudes and behaviors41. When focal employees feel deprived in such a way, they tend to generate adverse perceptions (e.g., a sense of unfairness) and negative emotions (e.g., depression) in the workplace. Consequently, it directly affects their efforts to perform required tasks (i.e., task performance) and their desire to go above and beyond the normal requirements of an organization (i.e., organizational citizenship behavior (OCB))42.

Borman & Motowidlo (1997) defined job performance as “work activities that contribute directly or indirectly to the organization’s core goals“43. In comparison, Ingold et al. (2015) divided job performance into task performance and OCB and proved that such a division holds scientific rationality16. Therefore, in reference to the division of job performance by Ingold et al. (2015), in this study, job performance is divided into task performance and OCB. Based on the reciprocity principle, Xu et al. (2012) also found that when employees suffer abuse from their superiors, they will respond to perceived inequalities in the organization by reducing their input into the organization, such as by decreasing task performance and out-of-role behavior44.

Therefore, we propose that when the RAS of focal employees is higher than that of other members of the group, they will feel a lower social status compared to other members and suffer relative deprivation, which undermines their job performance.

Hypothesis 3

RAS negatively affects employees’ task performance (H3a) and OCB (H3b) by increasing employees’ relative deprivation.

Hypothesis 4

ASV moderates the indirect effect of RAS on employees’ task performance (H4a) and OCB (H4b) by increasing employees’ relative deprivation in such a way that the negative effects are stronger when ASV is low, compared to when ASV is high.

Method

Sample and procedure

Participants were employees and immediate leaders of five medium-sized electronic manufacturing firms in a Chinese city. These particular firms were chosen because the authors collaborated with the managers of these firms before. Because of these social connections, the team was able to gain assistance during the data collection process. To control for common method bias, data were collected from employees and leaders at two time points over three months. To ensure sufficient communication between leaders and employees, respondents must be full-time employees who have worked in the team for more than six months. Following the suggestion of Mathieu et al. (2012)45, our questionnaires were initially distributed to 336 employees and 118 immediate leaders to ensure that the final sample size of the individual level sample was greater than 250 and the team level is greater than 51. The study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanchang University and were in line with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study. Participants were ensured that their personal data collected in and during the study remain confidential and that they can request the research team to withdraw their data from the study at any time. At time point 1, employees reported demographic information (i.e., age, gender, and tenure in the team) and assessed perceived abusive supervision by the leader. At time point 2 (3 months after time point 1), employees rated their relative deprivation level, and leaders were asked to assess their demographic information as well as evaluate the task performance and OCB of each member.

Surveys were recovered from 305 employees and 118 leaders at time point 1, as well as from 283 employees and 112 leaders at time point 2, resulting in a response rate of 93% for employees and of 95% for leaders. We deleted the invalid questionnaires that excessive items are missed or ticking the same option consecutively for the vast majority of questions. In addition, to ensure the validity of variables at the group level, the samples with fewer than two group members were excluded36. A final matched sample of 254 subordinates and 84 leaders was obtained for subsequent hypotheses testing and data analysis. A drop-out analysis was conducted, and missing samples presented no significant difference in demographic information. A multilevel statistical power test of cross-level interactions was conducted through a Monte Carlo program executable in R, justifying a large statistical power at the conventional alpha level of 0.05 and number of Monte Carlo replications of 100045. In the final sample, the group size ranged from a minimum of 3 to a maximum of 8. The average number of members in each group was 4.02 (SD = 1.08). Among leaders, most were male (72.3%), with ages mostly ranging from 31 to 35 years (29.5%) and 36 to 40 years (29.5%), and the average tenure as a leader was 12.8 years. Among employees, the average team tenure was 7.7 years, 67.1% were male, and most were aged 25–30 and 31–35 years (27.9% and 23.3%, respectively).

Measures

Abusive supervision and relative deprivation were measured using a seven-point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. For task performance and OCB, a similar five-point scale was adopted.

RAS and ASV

At time point 1, each employee assessed their own perception of abusive supervision using the measure developed by Tepper (2000), which consists of 15 items46. A sample item is “My superior often ridicules me”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.96.

According to Bliese et al. (2018)47—who proposed that the operationalization of group-mean centering can be used to assess the relative position in a group of individual variables—RAS was calculated by computing the value of focal employee perception of abusive supervision minus the group mean.

Drawing on the dispersion composition model48where individual-level rates are aggregated to reflect a group-level construct and following prior research (e.g., Todorova et al., 2015; Ogunfowora, 2013)11,49, the ASV score was operationalized for each group as the standard deviation of abusive supervision within a group. Because ASV is a group-level construct aggregated from individual perceptions of abusive subversion, the intraclass correlation (ICC1) for abusive supervision was calculated to be 0.28, which exceeds the threshold of 0.12, thus justifying its aggregation to the group level50.

Relative deprivation

At time point 2, group members assessed their relative deprivation using the five-item scale of Cho et al. (2014) (e.g., “I feel that I am unfairly treated”;= 0.87)41.

Task performance

The leaders evaluated the task performance of their subordinates at time point 2 through the five-item scale from Ingold et al. (2015)16. A sample item is “This employee achieves the objectives of the job.” ( = 0.84).

OCB

The OCB of the subordinate as reported by group leaders was measured at time point 2, using 14 items developed by Ingold et al. (2015)16. A sample item is “This employee often criticizes colleagues.” (α = 0.86).

Control variables

We controlled for subordinates’ gender and tenure at the individual level, as employees may respond differently to different genders and tenures when they are subjected to unfair treatment or interpersonal abuse51,52. At the group level, following prior studies, group size (i.e., the number of employees in the group) and group experience (i.e., the average tenure of group members) were controlled18.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents correlations among the research variables examined in this study. The correlations were moderate between RAS, the two dependent variables, and the proposed mediating mechanism of relative deprivation.

Confirmatory factor analyses

The confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to to test the measurement model and determine the validity of the questionnaire (see Table 2). The five-factor model (RAS, ASV, relative deprivation, task performance and OCB) fitted the data well (\(\:{\mathcal{X}}^{2}/\text{d}\text{f}\)= 1.55 < 3, p < .01, RMSEA = 0.05 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.06 < 0.08, CFI = 0.90 > 0.90, TLI = 0.90 > 0.90), and the fit was superior to that of alternative models.

Analytic strategy

Given the nested nature of the data (i.e., 254 employee-leader dyads were nested within 84 groups) and the fact that this study involved multilevel effects, multilevel analysis was conducted using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to test models53,54. Then, following the suggestion of Bliese et al. (2018)47, the Monte Carlo bootstrapping approach was applied to calculate the confidence intervals for hypothesized cross-level indirect effects.

The proportions of within- and between-group variance were tested for dependent variables. The ICC1 value for task performance was 0.20 > 0.12, for OCB, ICC1 = 0.29 > 0.12, indicating that a considerable portion of variance was nested in the group level which justified the use of multilevel analysis.

Hypotheses testing

The results of multilevel analyses are presented in Table 3. After including controls, Model 1 shows that RAS was positively related to relative deprivation (b = 0.48, p < .01), thus supporting H1.

Model 2 in Table 3 shows that the interactive effect of RAS and ASV on relative deprivation was significant (b = − 0.48, p < .05). A simple slopes test was also conducted to reflect the moderated effect more intuitively. Figure 2 shows that the positive direct effect of RAS on relative deprivation was stronger when the group has a lower ASV (slope = 0.51, p < .01) than when its ASV is high (slope = 0.16, p < .01), and the difference between them was significant (b = − 0.35, p < .01). This result supports H2.

Model 4 and Model 6 in Table 3 show that relative deprivation was both negatively related to task performance (b = − 0.16, p < .01) and OCB (b = − 0.19, p< .01). The mediation effects were further estimated using a bootstrapping method55. The indirect relationships mediated by relative deprivation between RAS and task performance (b = − 0.17, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [-0.28, − 0.09]), as well as between RAS and OCB (b = − 0.20, 95% SE = 0.05, CI = [-0.30, − 0.12] were significant, thereby supporting both Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

To test Hypothesis 4, the conditional indirect effect was examined using a Monte Carlo bootstrapping method56. The results showed that ASV moderated the indirect effect of RAS on task performance through relative deprivation was stronger when the group has a lower ASV (b = − 0.08, 95% bias-corrected CI = [-0.17, − 0.05]) than when ASV is high (b = − 0.03, 95% bias-corrected CI = [-0.15, 0.12]), and the difference between them was significant (b = 0.06, 95% bias-corrected CI = [0.00, 0.19]). It was similar on OCB that the indirect effect of RAS on task performance was stronger when ASV is low (b = − 0.10, 95% bias-corrected CI = [-0.17, − 0.05]) than when ASV is high (b = − 0.06, 95% bias-corrected CI = [-0.15, 0.12]), and the difference between them was significant (b = 0.07, 95% bias-corrected CI = [0.00, 0.19]). Thus ASV significantly moderated the indirect effect of RAS, supporting Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

Discussion

This study tested a model that clarifies how differentiation in abusive supervision on different levels affects employee performance using a muti-wave study including 254 employees and 85 leaders. The results show that ASV moderates the negative effect of RAS on task performance and OCB via relative deprivation. These effects of RAS are stronger when groups demonstrate lower levels of ASV. This study makes three contributions to the literature on abusive supervision, which are detailed in the following.

Theoretical implications

First, previous studies on the consequences of abusive supervision have commonly adopted the raw score approach (e.g., Mackey et al., 2019)5, while a relative perspective was rarely employed. While Schaubroeck et al. (2016) showed that in a group, if the behavior of the leader impacts employee perception of intragroup status, intragroup variation will be considered in that behavior15. Thus, our statistical model examined the individual-within-group component of abusive supervision (i.e., RAS). The research perspective is expanded to include the essence of the negative impact of abusive supervision: Employee perceived unfair treatment or relative deprivation is generated in comparison with other group members, making the research more convincing. This perspective also responds to the call by Martinko et al. (2013) to examine the perception component of abusive supervision57. Compared to abusive supervision, RAS is more harmful as it leads employees to infer their intragroup status and feel relatively deprived, which in turn undermines employee work outcomes.

Second, drawing on relative deprivation theory, this paper explains why a higher focal employee perception of abusive supervision compared to that of other group members results in more detrimental effects on job outcomes. These results prove that RAS perceived by employees can reduce their task performance and OCB by increasing their relative deprivation. Although prior studies have examined the affective mechanism of abusive supervision (e.g., negative affect)57, studies rarely explored the role of target-specific emotions in the response to RAS10. This verification of the relative deprivation mechanism provides a new theoretical perspective for the leadership dilemma, which unlocks a better understanding of the effectiveness of leadership from the perspective of intragroup social comparison. This enriches the understanding of the leadership process in the field.

Third, integrating relative deprivation theory with the “frog-pool effect” perspective, we provide initial evidence supporting the cross-level interaction effect between RAS and ASV. This evidence enriches the literature on the contextualization effect of abusive supervision. Prior research insisted that a studied phenomenon can only be clarified by disclosing the effect of the surroundings on the phenomenon58. The present study echoes the research demands of the above scholars and explored the moderating role of ASV. In addition, previous studies have shown that abusive supervision can exist at both individual and group levels. Few group-level studies on abusive supervision have been based only on a direct consensus construct (i.e., the abusive supervision climate)59. Further, few studies on abusive supervision used the current dispersion-based approach, while recent studies on other topics, such as research on LMX differentiation, have proved that group processes can be better understood when dispersion constructs are used37. Thus, this paper highlights the importance of using a dispersion construct (ASV) in groups for the future development of abusive supervision research.

Practical implications

This research provided practical contributions by shedding light on the differentiation phenomenon of abusive supervision, a relatively unexplored area in empirical studies. By utilizing the framework of relative deprived theory and introducing operational indicators of RAS and ASV, the study offered a nuanced understanding of how negative leadership impact group members within an group context. In a group, employees often intentionally or unintentionally compare how they are treated by their supervisors compared to other members to infer their relative position and adjust their work attitudes and behaviors accordingly. The findings emphasized that the negative influence of focal employees’ RAS on task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is mediated by the perception of relative deprivation. Managers should not only focus on the absolute value of abuse but also on the role of social comparison and carefully handle their relationship with subordinates. Leaders should avoid letting individuals in a group feel that they have been mistreated or abused specifically. Organizations must also articulate explicit policies asserting zero tolerance for leaders selectively subjecting certain employees (such as non-conformist individuals) to abuse.

Our study found that the negative effects of equivalent levels of RAS experienced by focal employees are more pronounced in groups with low levels of ASV. In other words, our study found that in certain cases, low ASV are not a good thing. While leaders are often said to be “give everyone an even bowl of water”. Our results told managers that, at least from the perspective of enhancing in-role performance or stimulating OCB, the equal is not the better when dealing with subordinates. It is just the expression of the ideal state from the perspective of morality and fairness. In the actual management, it is impossible and unnecessary to fully fairness, which will harm the effectiveness of the group. However, leaders must not use differentiated abuse as a political means to try to abuse each member in varying degrees, which will lead to conflicts within the group and make members feel psychological separation, which is the most disadvantageous way for groups. Therefore, on the premise of having to carry out abusive supervision, moderate differential abuse should also be implemented. Although the negative effect of relative abusive supervision is lowered when abusive supervision variability is high, we are by no means encouraging collective abuse in the group. Instead, we showcase that group context matters, and recommend that organizations and groups pursue ways to create a favorable environment where the negative consequences of relative deprivation may be alleviated.

In addition, although we did not find any direct evidence for this, we believe that leaders should not enact abusive supervision because of their own emotions or personalities. The reason is that it easily happens that employees think that the abuse they suffer is not due to their own behavior, which causes them to feel relative deprivation60. Maybe a leader should use job ability as the main criterion. Abusive supervision according to job ability can motivate members to believe that they can gain a higher position by improving their job performance, thus mobilizing the enthusiasm of all employees in the group.

Limitations and future directions

This study has certain limitations that open avenues for future research. First, data were collected in two waves where supervisors and employees were matched. While this research design controlled for common method variance or same source bias to a certain extent, the measurement of abusive supervision is sensitive and can produce a social approval effect. Therefore, different methods (such as in-depth interviews and field experiments) can be used to measure the abuse of supervisors in future research to explore the mechanism of abusive supervision. Second, the study sample is limited to five companies in one specific city. Although it is beneficial to control the scale, geography, and industry impact, this approach also somewhat limits the external validity of the model. Future studies can conduct more extensive surveys to further test the conclusions. Third, our study adopted a group-centric perspective, positing that the comparison between the level of abuse experienced by focal employees and that experienced by other group members determines their perceived relative deprivation and performance. However, aside from comparisons with others, focal employees also engage in a comparison of past experiences with present ones. Therefore, it is imperative to incorporate a temporal perspective into the study of abusive supervision. Future research could investigate whether differentiation in abusive supervision over time dimensions might impact subsequent employee coping behaviors.

Data availability

All data included in the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author through their email address upon reasonable request.

References

Hershcovis, M. S. Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my! A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. J. Organizational Behav.32 (3), 499–519 (2011).

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E. & Duffy, M. K. Predictors of abusive supervision: Supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Acad. Manag. J.54 (2), 279–294 (2011).

Boisot, M. & Child, J. The iron law of fiefs: bureaucratic failure and the problem of governance in the Chinese economic reforms. Adm. Sci. Q.33 (4), 507–527 (1988).

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R. & Martinko, M. J. Abusive supervision: a meta-analysis and empirical review. J. Manag.43 (6), 1940–1965 (2017).

Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Maher, L. P. & Wang, G. Leaders and followers behaving badly: a meta-analytic examination of curvilinear relationships between destructive leadership and followers’ workplace behaviors. Pers. Psychol.72 (1), 3–47 (2019).

Hannah, S. T. et al. Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviors: a moderated mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol.98 (4), 579–592 (2013).

Wang, C., Feng, J. & Li, X. Allies or rivals: how abusive supervision influences subordinates’ knowledge hiding from colleagues. Manag. Decis.59 (12), 2827–2847 (2021).

Matta, F. K., Scott, B. A., Koopman, J. & Conlon, D. E. Does seeing eye to eye affect work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior? A role theory perspective on LMX agreement. Acad. Manag. J.58 (6), 1686–1708 (2015).

Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., Harris, R. B. & Cast, M. An investigation of abusive supervision, vicarious abusive supervision, and their joint impacts. J. Soc. Psychol.153 (1), 38–50 (2013).

Ogunfowora, B., Weinhardt, J. M. & Hwang, C. C. Abusive supervision differentiation and employee outcomes: the roles of envy, resentment, and insecure group attachment. J. Manag.47 (3), 623–653 (2021).

Ogunfowora, B. When the abuse is unevenly distributed: the effects of abusive supervision variability on work attitudes and behaviors. J. Organizational Behav.34 (8), 1105–1123 (2013).

Kim, J. K., LePine, J. A., Zhang, Z. & Baer, M. D. Sticking out versus fitting in: a social context perspective of ingratiation and its effect on social exchange quality with supervisors and teammates. J. Appl. Psychol.107 (1), 95–108 (2022).

Johns, G. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad. Manage. Rev.31 (2), 386–408 (2006).

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M. & Bialosiewicz, S. Relative deprivation: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality Social Psychol. Rev.16 (3), 203–232 (2012).

Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C. & Hannah, S. T. The role of peer respect in linking abusive supervision to follower outcomes: dual moderation of group potency. J. Appl. Psychol.101 (2), 267–278 (2016).

Ingold, P. V., Kleinmann, M., König, C. J. & Melchers, K. G. Transparency of assessment centers: lower criterion-related validity but greater opportunity to perform? Pers. Psychol.69, 467–497 (2015).

Tepper, B. J., Simon, L. & Park, H. M. Abusive supervision. Annual Rev. Organizational Psychol. Organizational Behav.4, 123–152 (2017).

Priesemuth, M., Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L. & Folger, R. Abusive supervision climate: a multiple-mediation model of its impact on group outcomes. Acad. Manag. J.57 (5), 1513–1534 (2014).

Pan, S. Y. & Lin, K. J. Who suffers when supervisors are unhappy? The roles of leader–member exchange and abusive supervision. J. Bus. Ethics. 151 (3), 799–811 (2018).

Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J. & Oldham, G. R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: where should we go from here? J. Manag.30 (6), 933–958 (2004).

Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat.7 (2), 117–140 (1954).

Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., DeVinney, L. C., Star, S. A. & Williams, R. M. Jr The American Soldier: Adjustment during Army Life Vol. 1 (Princeton University Press, 1949).

Greenberg, J., Ashton-James, C. E. & Ashkanasy, N. M. Social comparison processes in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum Decis. Process.102 (1), 22–41 (2007).

Wood, J. V. What is social comparison and how should we study it? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.22 (5), 520–537 (1996).

Lin, X. et al. Psychological contract breach and destructive voice: the mediating effect of relative deprivation and the moderating effect of leader emotional support. J. Vocat. Behav.135, 103720 (2022).

Hu, J. I. A. & Liden, R. C. Relative leader–member exchange within team contexts: how and when social comparison impacts individual effectiveness. Pers. Psychol.66 (1), 127–172 (2013).

Moore, D. A. Not so above average after all: when people believe they are worse than average and its implications for theories of bias in social comparison. Organ. Behav. Hum Decis. Process.102 (1), 42–58 (2007).

Zhao, C., Gao, Z. & Liu, Y. Worse-off than others? Abusive supervision’s effects in teams. J. Managerial Psychol.33 (6), 418–436 (2018).

Davis, J. A. A formal interpretation of the theory of relative deprivation. Sociometry. 22 (4), 280–296 (1959).

Gabriel, A. S., Diefendorff, J. M., Chandler, M. M., Moran, C. M. & Greguras, G. J. The dynamic relationships of work affect and job satisfaction with perceptions of fit. Pers. Psychol.67 (2), 389–420 (2014).

Ilies, R. & Judge, T. A. Goal regulation across time: the effects of feedback and affect. J. Appl. Psychol.90 (3), 453–467 (2005).

Davis, J. A. The campus as a frog pond: an application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. Am. J. Sociol.72 (1), 17–31 (1966).

Salancik, G. R. & Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q.23 (2), 224–253 (1978).

Thibault, J. W. & Kelley, H. H. The social psychology of groups (John Wiley, 1959).

Liao, H., Liu, D. & Loi, R. Looking at both sides of the social exchange coin: a social cognitive perspective on the joint effects of relationship quality and differentiation on creativity. Acad. Manag. J.53 (5), 1090–1109 (2010).

Ma, L. & Qu, Q. Differentiation in leader–member exchange: a hierarchical linear modeling approach. Leadersh. Q.21 (5), 733–744 (2010).

Le Blanc, P. M. & González-Romá, V. A team level investigation of the relationship between leader–Member Exchange (LMX) differentiation, and commitment and performance. Leadersh. Q.23 (3), 534–544 (2012).

Matta, F. K., Scott, B. A., Guo, Z. Y. & Matusik, J. G. Exchanging one uncertainty for another: Justice variability negates the benefits of justice. J. Appl. Psychol.105 (1), 97–110 (2020).

Peng, A. C., Schaubroeck, J. M. & Li, Y. Social exchange implications of own and coworkers’ experiences of supervisory abuse. Acad. Manag. J.57 (5), 1385–1405 (2014).

Walker, I. & Smith, H. J. (eds) Relative Deprivation: Specification, Development, and Integration (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Cho, B., Lee, D. & Kim, K. How does relative deprivation influence employee intention to leave a merged company? The role of organizational identification. Hum. Resour. Manag.53 (3), 421–443 (2014).

Hu, J. et al. There are lots of big fish in this pond: the role of peer overqualification on task significance, perceived fit, and performance for overqualified employees. J. Appl. Psychol.100 (4), 1228–1238 (2015).

Borman, W. C. & Motowidlo, S. J. Task performance and contextual performance: the meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform.10 (2), 99–109 (1997).

Xu, E., Huang, X., Lam, C. K. & Miao, Q. Abusive supervision and work behaviors: the mediating role of LMX. J. Organizational Behav.33 (4), 531–543 (2012).

Mathieu, J. E., Aguinis, H., Culpepper, S. A. & Chen, G. Understanding and estimating the power to detect cross-level interaction effects in multilevel modeling. J. Appl. Psychol.97, 951–966 (2012).

Tepper, B. J. Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manag. J.43 (2), 178–190 (2000).

Bliese, P. D., Maltarich, M. A. & Hendricks, J. L. Back to basics with mixed-effects models: nine take-away points. J. Bus. Psychol.33 (1), 1–23 (2018).

Chan, D. Functional relationships among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: a typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol.83, 234–246 (1998).

Todorova, G., Qu, Y., Dasborough, M. T. & Zhou, M. With a Little Help from My Friends: Abusive Supervision, Team Member Exchange, and Creativity. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2015, No. 1, p. 12868). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management. (2015).

James, L. R. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J. Appl. Psychol.67 (2), 219–229 (1982).

Aquino, K. & Douglas, S. Identity threat and antisocial behavior in organizations: the moderating effects of individual differences, aggressive modeling, and hierarchical status. Organ. Behav. Hum Decis. Process.90 (1), 195–208 (2003).

Lam, C. K., Huang, X. & Chan, S. C. The threshold effect of participative leadership and the role of leader information sharing. Acad. Manag. J.58 (3), 836–855 (2015).

Liden, R. C., Erdogan, B., Wayne, S. J. & Sparrowe, R. T. Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: implications for individual and group performance. J. Organizational Behavior: Int. J. Industrial Occup. Organizational Psychol. Behav.27 (6), 723–746 (2006).

Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, Y. F., Congdon, R. T. & du Toit, M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling (Scientific Software International, 2011).

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D. & Hayer, A. F. Addressing moderated mediated hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res.42 (1), 185–227 (2007).

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J. & Zhang, Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol. Methods. 15 (3), 209–233 (2010).

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R. & Mackey, J. A review of abusive supervision research. J. Organizational Behav.34 (S1), S120–S137 (2013).

Bamberger, P. Beyond contextualization: using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Acad. Manag. J.51 (5), 839–846 (2008).

Jiang, W. & Gu, Q. How abusive supervision and abusive supervisory climate influence salesperson creativity and sales team effectiveness in China. Manag. Decis.54 (2), 455–475 (2016).

Crosby, F. A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychol. Rev.83 (2), 85–113 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20242BAB20011), the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Project of the Ministry of Education (24YJC630241); the Project Funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M741518), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XH and MT wrote the main manuscript text, DY designed the idea and prepared the tables and figures. HX and ZZ run the analyses. All authors performed and administered the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanchang University and were in line with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was signed and obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, H., Togola, M., Zhang, Z. et al. A relative deprivation perspective of the differentiation of abusive supervision in groups. Sci Rep 14, 22828 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74386-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74386-5