Abstract

Previous studies have yielded inconsistent results regarding the association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the risk of cognitive impairment (CI). This study aimed to investigate the longitudinal association of CKD with CI risk in the Chinese middle-aged and older population. A total of 16,515 CI-free participants 45 years of age or older including 15,595 without CKD and 920 with CKD were followed from 2011 until 2018 (median [interquartile range]: 7 [5.5-7]) to detect incident CI. Over the follow-up, 648 participants developed CI. Data were analyzed using multi-adjusted Cox proportional hazard regression and Laplace regression. The incidence rate (IR) of CI was significantly higher in individuals with CKD at 11.46 per 1,000 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.90 to 14.76) than in those without CKD at 6.38 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 5.89 to 6.92). Compared to those without CKD, the hazard ratios of those with CKD was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.19 to 2.04) for CI. Participants with CKD in the middle-aged group (45–54 years) exhibited a heightened risk of CI in age-stratified analyses. CKD accelerated the onset of CI by 1.24 years (10th percentile difference [PD]; 95% CI, -2.03 to -0.43, p < 0.01). The findings from this study revealed a significantly increased risk of CI in individuals with CKD, especially in middle-aged population, where the risk appeared to be more pronounced. This observation underscores the importance of early detection and intervention strategies to alleviate the potential cognitive decline associated with CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health issue with a rising prevalence that poses significant challenges to healthcare systems1. It is associated with a range of complications, including cardiovascular disease, anemia, and bone disorders2,3,4. Recent research has also highlighted a potential link between CKD and cognitive dysfunction, a condition that can severely impact the quality of life and independence of affected individuals5,6,7.

Cognitive dysfunction in the context of CKD is characterized by impairments in memory, executive function, and processing speed8,9. Although the exact mechanisms remain to be fully clarified, vascular damage, uremic toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation may contribute to the disease2,10. Despite the growing interest in this area, the literature on the relationship between CKD and cognitive impairment has yielded inconsistent results, with some studies reporting a significant association and others finding no clear link11,12,13,14.

This inconsistency may be due to methodological differences across studies, including variations in the definition of CKD, assessment of cognitive function, and the study populations7,15. In addition, many previous studies have been cross-sectional or have had short follow-up periods, which limits the ability to establish causality and to understand the progression of cognitive decline in relation to CKD16,17.

Given these limitations, there is a clear need for further research to better understand the relationship between CKD and cognitive dysfunction. The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) provides an ideal platform for such an investigation. This national survey, with its comprehensive and longitudinal design, offers a rich source of data on the health and well-being of midlife and older Chinese adults18.

This study aimed to investigate the association between CKD and incident cognitive impairment in the Chinese middle-aged and older population. This research will provide valuable insights into the temporal relationship between CKD and cognitive decline.

Materials and methods

Study population

CHARLS constitutes a representative sample of middle-aged and elderly individuals in China. The study’s methodology and design have been previously described in detail18. Launched from June 2011 to March 2012, the baseline survey implemented a multistage and stratified sampling strategy, enrolling 17,708 participants aged 45 and above from 450 villages in 28 provinces. Data collection was conducted through structured questionnaires administered in individual interviews. Follow-up assessments were conducted biennially, with physical examinations and blood sample collection every four years. The study received ethics approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University, Beijing (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided informed consent. By 2018, CHARLS had successfully completed three rounds of follow-up assessments. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

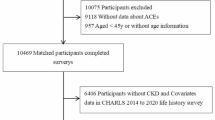

The present study represented a secondary analysis of data from the CHARLS, spanning from 2011 to 2018.Participants were exclusively selected from the CHARLS’s Wave 1 cohort. 194 cases with incomplete follow-up information and 56 participants with no follow-up data were excluded from the analysis to minimize potential bias. In addition, 620 individuals without baseline data on chronic kidney diseases were excluded. 323 patients with CI at baseline were excluded prior to the commencement of the study. Consequently, the final analysis encompassed a sample size of 16,515 participants. The participant selection process was depicted in supplementary Fig. 1.

The analysis revealed several potential confounders that necessitated adjustment at baseline, including sociodemographic factors (age, gender, marital status, and educational attainment), lifestyle and health behaviors (smoking and alcohol intake, along with the individual body mass index [BMI]), and diagnoses of various chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease [CVD], and stroke). Participants were surveyed regarding their medical diagnoses of the abovementioned chronic diseases. If the respondents provided an affirmative response or were currently taking medications for the management of chronic conditions, such as antihypertensive drugs, hypoglycemic agents, insulin injections, or lipid-lowering medications, they were categorized as having the respective chronic diseases.

Participants’ ages were categorized into three groups: 45–54, 55–64, and 65 years and older. Marital status was classified into two categories: married or cohabiting and other (encompassing separated, divorced, never married, widowed, or married but separated individuals). Education was stratified into three levels: below lower secondary, upper secondary or vocational, and tertiary. The smoking status was dichotomized into smoker and nonsmoker. Alcohol consumption was divided into drinkers and non-drinkers. BMI was allocated into four categories: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0 kg/m2), overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI < 28.0 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m2).

Identification of the CI and CKD

The primary endpoint of this study was CI, encompassing Alzheimer’s disease, brain atrophy, Parkinson’s syndrome, and other memory-related disorders, with the specific etiology of CI remaining unspecified. CI status was determined through interviews conducted by trained personnel who inquired, “Have you been diagnosed with a memory-related condition, such as Alzheimer’s disease, brain atrophy, or Parkinson’s disease, by a medical professional?” Positive responses prompted further inquiry regarding the timing of diagnosis and current medication use. The presence of CKD was determined at the baseline survey with the query: “Have you been diagnosed with kidney disease, excluding renal tumors and cancer, by a physician?” Affirmative responses resulted in the classification of participants as having CKD, followed by an inquiry into the timing of their diagnosis. The diagnostic criteria for CKD and CI, based on self-reported diagnoses, are consistent with those used in previous studies that have utilized the CHARLS dataset19,20.

Statistical analyses

We utilized the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to verify the normality of the continuous variables in our large sample study. Subsequently, Depending on whether the continuous variables exhibit normality, either the t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For categorical variables, the chi-square test was employed. Missing values were addressed through multiple imputation using chained equations implemented via the “mice” package in R.

The primary endpoint of this study was the incidence of CI, whereas the secondary endpoint was all cause mortality. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival were assessed using a stratified log-rank test. The association between CKD and the risk of CI during the follow-up period was evaluated using Cox proportional hazard regression, excluding patients with prevalent CI at baseline. Data were censored at the earliest occurrence of CI, death, or July 2018. Proportional hazard assumptions were confirmed using Schoenfeld residual plots. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Three adjusted models were developed: Model 1 included adjustments for age and gender; Model 2 added adjustments for education, marital status, lifestyle habits including smoking, drinking, and BMI; and Model 3 further incorporated comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD, and stroke.

Using Stata software, we calculated the incidence rates (IRs) of CKD leading to CI or mortality, expressed as incidents per 1,000 person-years with their corresponding 95% CIs. Laplace regression was applied to model the time to incident CI or mortality in relation to kidney status, which evaluated the variability in time to events. As less than 11% of cohort participants experienced the outcomes, we analyzed the median time (in years) until the initial 10% of the cohort faced CI or mortality. This analysis was conducted using the “laplacereg” command in Stata.

Stratified and interaction analyses were conducted to evaluate the varying impact of kidney disease across distinct subgroups, using baseline characteristics as covariates. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was reapplied after stratification by age, sex, BMI, presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cvd, and stroke. Statistical significance of the interaction was determined by including interaction terms and the execution of likelihood ratio tests.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted. To alleviate the impact of confounding variables, inverse probability weights (IPW) were computed for each participant. The effectiveness of the weighting was assessed by evaluating the standardized mean difference (SMD) of covariates between the weighted populations, with SMD < 0.1 indicating an adequate balance of covariates across groups. The main analysis was subsequently conducted using the weighted data. The Fine and Gray competing risk model was applied to assess the competing risk of mortality relative to the occurrence of CI. The main analyses were repeated in a population that excluded individuals who developed CI within the first 2 years of the follow-up period. To mitigate the risk of including CI events attributable to comorbid chronic conditions, the main analyses were also conducted in a cohort that excluded participants with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, CVD, and stroke at baseline.

We employed two-sided P-values, with the level of significance set at α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.3) and Stata statistical software (version 17.0).

Results

Social demographic characteristics of participants

The study population was categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of CKD at baseline, as detailed in Table 1. The average age of the participants did not exhibit significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.737). A significantly higher proportion of males was identified within the CKD group (52.61% vs. 48.42%, p = 0.015). No significant differences in educational attainment, marital status, alcohol consumption, smoking status, or BMI were detected between the groups (p > 0.05). However, a markedly elevated prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, CVD, and stroke was observed in individuals with CKD (p < 0.01). Comprehensive data were provided in Table 1.

Associations between CKD and the risk of CI

Over a median follow-up period of 7 years (interquartile range [IQR], 5.5 to 7.0 years), 648 participants developed CI. The IR of CI was significantly higher in individuals with CKD at 11.46 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 8.90 to 14.76) than in those without CKD at 6.38 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 5.89 to 6.92). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves indicated a lower probability of survival in the CKD cohort, indicating an elevated risk of CI (p < 0.001, Fig. 1A). The Cox proportional hazard models further supported the association (Table 2). In the initial model (Model 1), adjusted for age and sex, the HR for CI in the CKD group was 1.85 (95% CI, 1.42 to 2.42). Subsequent adjustments for education, marital status, alcohol consumption, smoking, and BMI (Model 2) minimally altered HR to 1.84 (95% CI, 1.41 to 2.40). Further adjustments for comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, CVD, and stroke (Model 3) yielded a modestly reduced but still significant HR of 1.56 (95% CI, 1.19 to 2.04). Laplace regression analysis predicted that CI onset would occur 1.24 years earlier in CKD patients than in non-CKD participants (10th percentile difference [PD]; 95% CI, -2.03 to -0.43, p < 0.01, Fig. 2A).

Associations between CKD and mortality

1,667 participants died during the follow-up period. The IR of mortality was markedly elevated in the CKD group (20.42; 95% CI, 17.07 to 24.51) versus the non-CKD group (16.01; 95% CI, 15.23 to16.83). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that individuals with CKD exhibited a lower survival probability than those without CKD (p < 0.001, Fig. 1B). The cox regression analysis results showed that the HR value was 1.34 (95% CI, 1.11–1.61) in Model 1 and then slightly decreased to 1.25 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.51) in the fully adjusted model 3 (Table 2). Laplace regression analysis showed that the risk of mortality in CKD individuals was not significantly higher than that in non-CKD individuals (10th PD 0.11, 95%CI, -0.69 to 0.47, p = 0.71, Fig. 2B).

Stratified analysis

In age-stratified analyses (45–54 years: n = 6065; 55–64 years: n = 6173; >= 65 years: n = 4277), participants with CKD in the midlife group (45–54 years) exhibited a heightened risk of CI. This association progressively diminished with advancing age, losing statistical significance among those aged 65–74 years. Furthermore, no significant interaction between CKD and age on mortality risk was identified (p = 0.85). Similarly, no significant interactions were observed between CKD and either sex or BMI on the risks of both CI and mortality (p > 0.05, as depicted in Fig. 3). In combination with hypertension, diabetes, and stroke, the risk of CI or death in patients with CKD did not reach statistical significance, although the risk was increased compared with the risk in the absence of these conditions (p > 0.05, Fig. 3).

Sensitivity analysis

IPW analyses were employed to standardize the baseline covariates between participants with and without CKD. The participant characteristic after the IPW adjustment was detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The findings from the IPW analyses were in alignment with the principal results (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, a competing risks analysis was performed to account for the impact of death on the occurrence of CI. The results of this analysis were consistent with the main results and presented in Supplementary Table 3. When participants who developed CI within the first 2 years of follow-up or those with concurrent hypertension or diabetes were excluded, the incidence of CI remained significantly higher among CKD participants than among their non-CKD counterparts (Supplementary Tables 4, 5, 6). However, the statistical significance of this risk was lost after excluding patients with comorbid CVD (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that 648 participants experienced CI, and 1,667 individuals died within a national longitudinal cohort study during a median follow-up of 7 years. The incidence rates for both CI and mortality were significantly higher in the CKD cohort than in those without CKD. After full adjustment, the HRs for CI and mortality in the CKD group were 1.56 (95% CI, 1.19 to 2.04) and 1.25 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.51), respectively. Additionally, the risk of CI incidence was greater among midlife individuals than among aged adults. The onset of CI was anticipated to occur 1.24 years earlier in patients with CKD than in those without (10th percentile difference [PD]; 95% CI, -2.03 to -0.43).

The results of our study, which demonstrated a significant association between CKD and CI, were consistent with the findings of several longitudinal studies. one recent study showed that the HRs of those with impaired kidney function was 1.48 (95% CI,1.15 to 1.90)/1.44 (95% CI,1.10 to1.88) for dementia/Alzheimer’s dementia compared with those with normal kidney function in a community-based cohort21. The result from Framingham Heart Study suggested that CKD was associated with a higher risk of incident dementia (HR = 1.53, 95%CI,1.02 to 2.29) and vascular dementia (HR = 2.78, 95%CI,1.16 to 6.68)22. One systematic review showed that worse kidney function (classification based on urinary albumin creatinine ratio [UACR]) was related to a greater risk of global brain cognitive disorder (RR = 1.28, 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.36) by analysis of 28 prior longitudinal studies7. These studies have collectively contributed to the growing body of evidence supporting a link between CKD and cognitive health.

However, research results on the increased risk of CI in the CKD population are not consistent. The emergence of this discrepancy may be attributable to several factors. First, CI may be related to the severity or stage of CKD. Studies had shown that the risk of developing CI significantly increased only in patients with severe CKD (stage 4), whereas this risk was not significant in patients with mild to moderate CKD (stage 3a and b)23,24,25. Second, there is no unified standard for renal function assessment indicators among patients with CKD. It had been shown that estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)cys offered improved sensitivity over eGFRcr in the determination of renal function and associated risk of CI26,27. Another study showed that a higher urinary albumin to creatinine ratio, but not a lower eGFR, was associated with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia7. Finding more accurate renal function markers or optimizing existing evaluation indicators requires further research.

Our findings highlighted the importance of age as a modifying factor in incident CI among patients with CKD. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, it was observed that the HR for incident dementia among patients with CKD in midlife (age 54–74 years) was significantly higher (HR = 3.44, 95% CI, 2.33 to 5.08) compared to that in aged patients (age 70–90 years) (HR = 1.93, 95% CI, 1.20 to 3.11)28. Another community-based study indicated that while there was a trend toward a gradual decrease in the risk of dementia among patients with CKD as age increases, no statistically significant difference was observed17. Midlife individuals with CKD had a greater risk of CI incidence than aged individuals in our study, suggesting that early interventions may be particularly beneficial in the demographics. This insight can guide public health strategies and healthcare practices to focus on midlife patients with CKD for preventive measures against CI.

Recent research from the UK Biobank indicates that among individuals with a high genetic risk for dementia, characterized by the presence of the ApoE ε4/ε4 or ε3/ε4 genotypes, the association between CKD and the risk of developing dementia appears to be weaker compared to those with a normal (ε3/ε3) or lower (ε2/ε2 or ε3/ε2) genetic risk29. Additionally, a study conducted in a Chinese population suggests that there is no significant interaction between the risk of developing dementia in CKD patients and the presence of the APOE-ε4 allele30. Therefore, the role of the APOE-ε4 allele in increasing the risk of dementia in CKD patients requires further investigation.

This study has several strengths. First, the results could be extrapolated to a larger Chinese population because of the use of CHARLS dataset, a nationally representative study with a sizable sample size. Second, the long follow-up period allowed for a comprehensive, longitudinal examination of the connection between CKD and CI. Third, to identify the real relationship between CKD and CI, the researchers cautiously adjusted for various potential confounders, including lifestyle and sociodemographic factors. Finally, the addition of stratum and sensitivity analyses strengthened the study’s overall strength and increased the validity of the conclusions drawn from it.

This study acknowledged a few limitations. First, selection bias may have been created by excluding participants whose primary variable data were incomplete, which would have affected the generalizability of the results. Second, recall bias may be introduced by relying solely on self-reported data for CKD, which could affect the accuracy of the information gathered. Third, even after accounting for a variety of potential confounders, the results might have been impacted by the lack of control over variables like the urine albumin to creatinine ratio or estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Conclusions

In summary, our research findings revealed a significantly increased risk of CI in individuals with CKD, especially in middle-aged population, where the risk appeared to be more pronounced. This observation underscores the importance of early detection and intervention strategies to alleviate the potential cognitive decline associated with CKD. Further investigation is necessary to understand the underlying mechanisms contributing to this heightened susceptibility and to develop targeted approaches for the preservation of cognitive function in patients with CKD.

Data availability

The CHARLS data used in this work are publicly available; they are unrestricted use data that any researcher can obtain from the CHARLS website. The URL is https://charls.charlsdata.com/.

Abbreviations

- CHARLS:

-

Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- CI:

-

Cognitive Impairment

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- HRs:

-

Hazard Ratios

- CIs:

-

Confidence Intervals

- IPW:

-

Inverse Probability Weights

- SMD:

-

Standardized Mean Difference

- PD:

-

Percentile Difference

- eGFR:

-

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

References

Francis, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6

Ketteler, M. et al. Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder: Synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2017 clinical practice Guideline Update. Ann. Intern. Med. 168, 422–430 (2018).

Levin, A. Therapy for Anemia in chronic kidney disease - new interventions and new questions. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 1657–1658 (2021).

Zoccali, C. et al. Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 733–746 (2023).

Janelidze, S., Barthélemy, N. R., He, Y., Bateman, R. J. & Hansson, O. Mitigating the associations of kidney dysfunction with blood biomarkers of Alzheimer Disease by using phosphorylated tau to total tau ratios. JAMA Neurol. 80, 516–522 (2023).

Lau, W. L. & Fisher, M. New insights into cognitive decline in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 214–215 (2023).

Tang, X. et al. Association of kidney function and brain health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 82, 101762 (2022).

Kurella Tamura, M. et al. Loss of executive function after dialysis initiation in adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 91, 948–953 (2017).

Mendley, S. R. et al. Duration of chronic kidney disease reduces attention and executive function in pediatric patients. Kidney Int. 87, 800–806 (2015).

Viggiano, D. et al. Mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction in CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 452–469 (2020).

Helmer, C. et al. Chronic kidney disease, cognitive decline, and incident dementia: the 3 C study. Neurology. 77, 2043–2051 (2011).

Koop-Nieuwelink, C. et al. Kidney function and the risk of stroke and dementia: the Rotterdam Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 67, 821–826 (2019).

Kurella Tamura, M. et al. Cognitive impairment and progression of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 68, 77–83 (2016).

Tseng, T. J., Yen, Y. T., Yang, Y. H., Chen, Y. H. & Chan, T. C. Association between the occurrence of albuminuria and the risk of early dementia among older people upon health examination: a community-based cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 10, e041664 (2020).

Deckers, K. et al. Dementia risk in renal dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Neurology. 88, 198–208 (2017).

Scheppach, J. B. et al. Association of kidney function measures with signs of Neurodegeneration and Small Vessel Disease on Brain magnetic resonance imaging: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 81, 261–269e1 (2023).

Stocker, H. et al. Association of kidney function with development of Alzheimer Disease and other dementias and dementia-related blood biomarkers. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2252387 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68 (2014).

Jiang, B. et al. Association of Self-Reported Nighttime Sleep Duration with chronic kidney disease: China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Am. J. Nephrol. 54, 249–257 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Temporal trends and disparities of population attributable fractions of modifiable risk factors for dementia in China: a time-series study of the China health and retirement longitudinal study (2011–2018). Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 47, 101106 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Association of impaired kidney function with dementia and brain pathologies: a community-based cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 2765–2773 (2023).

Kelly, D. M. et al. Impaired kidney function, cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive disorders: the Framingham Heart Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. gfae079 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfae079

Foster, R. et al. Cognitive impairment in Advanced chronic kidney disease: the Canadian Frailty Observation and interventions Trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 44, 473–480 (2016).

Grasing, M., Kennedy, K., Sarnak, M. J., Burns, J. M. & Gupta, A. Mild to moderate decrease in eGFR and cognitive decline in older adults. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 37, 1499–1506 (2022).

Zijlstra, L. E. et al. The association of kidney function and cognitive decline in older patients at risk of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal data analysis. BMC Nephrol. 21, 81 (2020).

Guerville, F. et al. Kidney function and cognitive decline in older adults: examining the role of Neurodegeneration. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 651–659 (2021).

Paterson, E. N. et al. Association of renal impairment with cognitive dysfunction in the Northern Ireland Cohort for the Longitudinal Study of Ageing (NICOLA). Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 36, 1492–1499 (2021).

Scheppach, J. B. et al. Albuminuria and estimated GFR as risk factors for dementia in midlife and older age: findings from the ARIC Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, 775–783 (2020).

Yeh, T. S. et al. Kidney function, albuminuria, and their modification by genetic factors and risk of incident dementia in UK Biobank. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 138 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Kidney function and dementia risk in community-dwelling older adults: the Shanghai Aging Study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 13, 21 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research staff and all of the CHARLS participants for their participation in data collection. This analysis uses data or information from the Harmonized CHARLS dataset and Codebook, Version D as of June 2021 developed by the Gateway to Global Aging Data. The development of the Harmonized CHARLS was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG030153, RC2 AG036619, R03 AG043052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and S.W. H.X. contributed to the conception and design of the study. Y.S., S.W., C.W, and H.Z. performed the statistical analysis of the data. Y.S., X.G, and Y. G contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.S. and S.W. wrote the first draft of the article. Z.G, H.X., and Z.W. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shang, Y., Wang, S., Wei, C. et al. Association of chronic kidney disease with cognitive impairment risk in middle-aged and older adults: the first longitudinal evidence from CHARLS. Sci Rep 14, 23265 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74420-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74420-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between baseline cardio-kidney-metabolic syndrome, its transition and cognitive impairment: result from CHARLS study

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)

-

Intradialytic cognitive and physical exercise for enhancing cognitive function in haemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Renal Replacement Therapy (2025)