Abstract

High-sensitivity acceleration sensors have been independently developed by our research group to detect vibrations that are > 10 dB smaller than those detected by conventional commercial sensors. This study is the first to measure high-frequency micro-vibrations in muscle fibers, termed micro-mechanomyogram (MMG) in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PwPD) using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. We specifically measured the extensor pollicis brevis muscle at the base of the thumb in PwPD and healthy controls (HC) and detected not only low-frequency MMG (< 15 Hz) but also micro-MMG (≥ 15 Hz), which was preciously undetectable using commercial acceleration sensors. Analysis revealed remarkable differences in the frequency characteristics of micro-MMG between PwPD and HC. Specifically, during muscle power output, the low-frequency MMG energy was greater in PwPD than in HC, while the micro-MMG energy was smaller in PwPD compared to HC. These results suggest that micro-MMG detected by the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor provides crucial information for distinguishing between PwPD and HC. Moreover, a deep learning model trained on both low-frequency MMG and micro-MMG achieved a high accuracy (92.19%) in classifying PwPD and HC, demonstrating the potential for a diagnostic system for PwPD using micro-MMG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acceleration sensors based on microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) have been investigated and widely used in various electronic systems and medical applications1,2. Achieving high performance in MEMS accelerometers requires technological advancements that enable micro-G (1G = 9.8 m s−2) level sensing in a small sensor size3,4. Unlike conventional silicon-based MEMS accelerometers5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, our research is the first globally to propose and develop a multilayer metal-based MEMS accelerometer, using gold as its main component, realizing a highly sensitive acceleration data measurement system17,18,19,20. Specifically, we developed an acceleration sensor with great sensitivity to vibration than commercial sensors as previously reported21,22. Consequently, the noise floor was reduced by over 10 dB,and sensitivity was improved compared to commercial sensors21, allowing our acceleration sensor to detect information previously hidden beneath the noise floor of commercial acceleration sensors. Moreover, we successfully measured weak muscle vibrations in a healthy young individual by attaching our highly sensitive acceleration sensor to the skin, identifying a phenomenon we term micro-mechanomyogram (micro-MMG)21,22. Micro-MMG represents the micro-vibration component of the MMG, where MMG is defined as the oscillations associated with the long-axis shortening and lateralization of muscle fibers23. Surprisingly, micro-MMG could only be measured using our high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, not with commercial sensors. This type of micro-vibration from the body holds remarkable potential as a new information carrier.

Micro-vibrations from the body have the potential to be valuable in clinical diagnosis for detecting signs of disease. Parkinson’s disease (PD), an incurable progressive neurodegenerative disorder often accompanied by characteristic body vibrations24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, is caused by dopamine-secreting cell degeneration in the substantia nigra, thereby depleting the dopamine supply. No definitive treatment for PD exists, and as the disease is progressive, early detection and treatment are crucial. The disease typically manifests as motor symptoms, including limb tremors, impaired postural reflexes, muscle rigidity, and immobility. These visible motor symptoms, including impaired postural reflexes and tremors, are accompanied by mechanical body vibrations. Therefore, previous researchers have attempted to classify PD by measuring body vibrations using acceleration sensors. Jeon et al33,34. measured acceleration data in the tremor frequency range using two common inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensors attached to the wrist and middle finger of patients with PD (PwPD) and employed traditional machine learning models. Similarly, Kim et al35. measured acceleration data in the tremor frequency band using two common IMU sensors attached to the wrist and middle finger of PwPD and developed a deep learning model. These studies have reported a relationship between visible motor symptoms and MMGs as muscle vibrations in PwPD. However, the measurement of muscle vibrations in PwPD using high-sensitivity acceleration sensors and the exploration of their importance as information carriers have yet to be investigated.

Given the aforementioned information, the key issue remaining is that the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor has not yet been applied to the measurement of muscle vibrations in PwPD. Furthermore, the characteristics of micro-MMG related to PD and its potential for PD diagnosis have not been clarified. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to measure muscle vibrations in PwPD using the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and investigate the potential of micro-MMG in PD diagnosis. The first approach involves measuring muscle vibrations in PwPD with the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and investigating the characteristics of micro-MMG. In particular, we focus on analyzing vibration characteristics, including micro-vibrations in the high-frequency band, which can be measured for the first time using this sensor. We also compare the characteristics of the high-frequency micro-MMG, newly emphasized in this study, with the low-frequency MMG that has traditionally received attention. The second approach involves investigating the potential for classifying PD using a deep learning model trained on a dataset of muscle vibrations from PwPD. Crucially, this dataset includes both micro-MMG and low-frequency MMG, used simultaneously for analysis.

Methods

To measure micro-MMG, a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor was used to simultaneously measure and analyze the patient’s motor symptoms and micro-MMG. This clarified the characteristics of motor symptoms and micro-MMG in PwPD compared with healthy controls (HC). The participants were PwPD diagnosed by a PD specialist and HC as age-matched healthy older adult participants. This allowed us to compare the characteristics of PwPD and HC. As a sensor for measuring micro-MMG, a sensor module equipped with both a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and a commercial acceleration sensor was used by storing it in a sensor box. This allowed the micro-MMG measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor to be compared with MMG data measured using a commercial acceleration sensor.

The target for measuring MMG data was the extensor pollicis brevis muscle, which has a previously established record for measuring MMG data21, as well as the hand in which motor symptoms occur in PwPD. Hence, we are the first to measure micro-MMG in PwPD. Regarding the measurement conditions, in PwPD, both resting and exercise tremors, each with different characteristics, are noted as separate diagnostic findings27. Two conditions were used: the Rest condition, which involved relaxation and weakness and no exercise, and the Pinch condition, which involved muscular output as exercise, making it possible to analyze changes in the characteristics of PwPD and HC MMG data between these conditions. The measurement procedure involved attaching a sensor box with a sensor module to the extensor pollicis brevis muscle of the participant, measuring MMG data using a sensor module, and collecting time-series data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and a commercial acceleration sensor. MMG data were subjected to frequency analysis based on power spectral density (PSD), and the PSD distributions were compared between PwPD and HC. Moreover, using the energy value based on the integral processing of the PSD in the frequency direction, the energy difference value of the Pinch condition for the Rest condition was calculated and used as an evaluation index, and the statistically significant difference between the characteristics of PD and HC was investigated.

Next, we proceeded to build a diagnosis system using motor symptoms and micro-MMG as information sources. To achieve this, we built a system that automatically classified PwPD and HC using information on both the patient’s motor symptoms and micro-MMG measured simultaneously using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. Specifically, since information on both motor symptoms and micro-MMG could be measured using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, a dataset was created using the MMG data measured under the Rest and Pinch conditions as input data and the binary labels of PD and HC based on the epidemiological data for the diagnosis results of a PD specialist doctor as training data. Subsequently, to examine the effectiveness of using motor symptoms and micro-MMG as information sources for PD classification, a dataset was created based on motor symptoms which consisted of low frequency MMG data, a dataset based on micro-MMG, which consisted of high-frequency MMG data, and a dataset based on both motor symptoms and micro-MMG, which consisted of both low and high-frequency MMG data. Since these datasets entailed time-series classification problems, we evaluated the classification accuracy using the multivariate long short-term memory-fully convolutional networks (MLSTM-FCNs) for time series classification36, a typical deep learning model that shows high performance in this field.

Method for measurement of micro-mechanomyogram and motor symptoms

Measurement system

We used a high-resolution, small-sized, high-sensitivity acceleration sensor developed by our research group21,22. It is generally known that the sensitivity of capacitive MEMS acceleration sensor depends on Brownian noise, a type of thermomechanical noise6. This Brownian noise is inversely related to the mass of the proof mass5. In conventional silicon (Si)-based MEMS accelerometers, the size of the capacitive MEMS accelerometer has been increased to achieve low Brownian noise. Conversely, our research group21 focused on the fact that the density of gold (19.3 g cm−3) is approximately 10 times higher than that of Si (2.3 g cm−3) and found that improving the sensitivity of capacitive MEMS acceleration sensors is possible. Gold was used as the proof mass material to achieve a small sensor size. The previous study then developed a gold-proof mass-based capacitive MEMS acceleration sensor using multi-layer metal technology17,19,20,37. Hence, our research group was able to create a highly sensitive acceleration sensor with Brownian noise of less than 200 µG/√Hz (1 G = 9.8 m s−2).

Based on the developed high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, we implemented a sensor module for measuring MMG21,22. Figure 1a shows a block diagram of a sensor module consisting of the developed high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, a capacitance digital converter AD7745 (Analog Devices Inc.), and a commercial acceleration sensor MPU6050 (TDK InvenSense Inc.)38 as a reference acceleration sensor and demonstrates the device itself. These devices were installed on a module board (20 × 15 mm). The developed high-sensitivity sensor was manufactured using multi-layer metal technologies such as gold plating and sacrificial film processes. Sensing data are transferred to a microcontroller via an inter-integrated circuit interface and then to a computer via Universal Serial Bus (USB) communication. This allows the personal computer (PC), via the microcontroller, to record time-series data on vibrations in the sensor module part measured simultaneously by both a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor (sampling frequency: 87.2 Hz) and a commercial acceleration sensor (sampling frequency: 90 Hz).

High-sensitivity acceleration sensor and experimental setup. (a) High-sensitivity acceleration sensor and sensor module21,22. (b) Power spectral density of noise floor in the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor21,22. (c) Experimental scene including sensor box housing sensor module, microcontroller, and PC. Note that this figure is included in the published paper with written informed consent from the participant in the figure. (d) Sensor module position on flexor pollicis brevis muscle. (e) Measurement conditions consisting of Rest and Pinch conditions. CDC, capacitance digital converter; I2C, inter-integrated circuit; PC, personal computer; USB, Universal Serial Bus.

Since the noise floor level of the sensor module was an important factor for detecting micro-MMG, a previous study used the frequency PSD of acceleration (dB/Hz−1) to evaluate the noise floor level21. Experimental results showed that the noise floor of our highly sensitive acceleration sensor was < 100 µG/√Hz, and the noise floor of the commercial acceleration sensor was approximately 200 µG/√Hz. As shown in Fig. 1b, the commercially available sensor has a noise floor of -70 [dB/Hz] (≒10×log10([200 µG/√Hz]2), while the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor has a noise floor of <-80 [dB/Hz] (≒10×log10([100 µG/√Hz]2) and > 10 dB/Hz. A reduction in the noise floor level has been shown.

Measurement target and measurement conditions

MMG was measured using the muscle belly of the superficial head of the flexor pollicis brevis muscle, because the fingers are one of the representative body parts in which motor symptoms in PwPD are likely to occur. Signs of PD are observed in peripheral micro movements and tremor features25,27. Moreover, a previous study suggested that MMG can be measured by attaching an acceleration sensor to the flexor pollicis brevis muscle in the palm of the hand; therefore, we focused on this for the target position of measuring MMG21. Therefore, a sensor box in which a sensor module containing a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and a commercial acceleration sensor to be compared was housed and fixed was attached to the dominant hand of a sitting experiment participant (Fig. 1c): note that this figure is included in the published paper with written informed consent from the participant in the figure). Specifically, it was attached on the skin surface of the muscle belly of the superficial head of the flexor pollicis brevis muscle located at the base of the thumb of the finger (Fig. 1d).

Two conditions were investigated: a resting state in which no force was applied to the flexor pollicis brevis muscle of the finger and the muscle is relaxed (Rest condition) (top of Fig. 1e), and a pinching state in which force was applied and the muscle exercised (Pinch condition) (bottom of Fig. 1e). These two types of conditions were used as measurement conditions. The characteristics of finger muscle vibration in PwPD differ between cases in which the finger muscles are at rest without movement (hand vibration at rest) and cases in which the finger muscles are active (hand vibration during exercise)25,27. Therefore, by measuring the MMG data for the extensor pollicis brevis under both the Rest and Pinch conditions using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and analyzing the muscle sound data, we investigated whether the micro-MMG contain information related to PD. In the Rest condition, participants placed their arms on a designated table and relaxed and rested. In the Pinch condition, the participants placed their arms on the table and pinched a designated member with force between their thumb, index finger, and middle finger. To maintain force on the fingers, clothespins with a cube sandwiched between the backs as the designated member were used (bottom of Fig. 1e). The cube was made by cutting an eraser, and its size was a rectangular parallelepiped of 22 × 22 × 10 mm. Therefore, during the Pinch condition, the participants maintained a distance of 22 mm between their thumb and other fingers and applied force in the direction of pinching the clothespin. Acceleration data for the Rest and Pinch conditions were measured three times each for each participant.

Measurement procedure

Experiments were conducted based on the experimental procedure shown in the block chart in Fig. 2a. First, the location of the extensor pollicis brevis muscle of the participant’s dominant hand was identified. A sensor box containing a sensor module including a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and a commercial acceleration sensor was placed on the skin at the extensor pollicis brevis muscle. The sensor box was fixed to the palm of the hand using tape. The microcontroller, to which the sensor box is connected via a USB cable, was fixed to the forearm with a Velcro band. The microcontroller was further connected to a PC via a USB cable. After completing these preparations, the acceleration data for both the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and the commercial acceleration sensor could be measured simultaneously and recorded on the PC (Fig. 2b).

The participants were provided with verbal instructions regarding the measurement conditions by the experimenter, and the posture of their hands and fingers was prepared on the table, according to the measurement conditions. For the measurement conditions, either the Rest or Pinch condition was randomly taught based on counterbalance. Next, measurement of acceleration data using both the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and commercial acceleration sensor began simultaneously. Immediately after the start of the measurement, the experiment participant followed the experimenter’s cues and returned the forearm to its original position by flexing and extending the forearm while keeping the elbow on the table. This forearm bending and stretching movement was performed to synchronize the measurement start timings of the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and the commercial acceleration sensor. After the forearm returned to the table, acceleration data were measured for 30 s using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and commercial acceleration sensor. After 30 s, the measurement was stopped. These experimental procedures were repeated until the acceleration data for the Rest and Pinch conditions were measured three times each.

Experimental participants

Twenty-eight right-handed participants without musculoskeletal disorders participated in the experimental task: 10 healthy individuals without neurological disorders and 18 PwPD. The HC group consisted of 10 healthy older adult participants (mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age: 71.3 (± 6.0) years old; height: 165.6 (± 6.7) cm; weight: 63.9 (± 8.7) kg; sex: seven men and three women). The PD group consisted of 18 PwPD (mean [± SD] age: 70.2 (± 8.5) years old; height: 164.3(± 8.9) cm; weight: 56.2 (± 12.0) kg; sex: 11 men and 7 women, modified Hoehn–Yahr (HY) scale: 2.3 [± 0.9]). Patients diagnosed with PD by a PD specialist participated. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanto Central Hospital and Tokyo Institute of Technology Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent before participation. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations.

Evaluation index

The dataset to be analyzed was created using epidemiological data labels of the participants and MMG data as acceleration data for the extensor pollicis brevis muscle. Epidemiological data labels for participants were determined based on the diagnosis based on modified-HY by a PD specialist physician. Two labels, PD and HC, were used. MMG data for the extensor pollicis brevis muscle were measured using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and a commercial acceleration sensor. There were 10 and 18 participants in the HC and PD groups, respectively. For each participant in the experiment, MMG data for the Rest condition were measured three times as were MMG data for the Pinch condition. Therefore, 30 and 54 data samples for HC MMG and PD MMG, respectively, were included for each of the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor and commercial acceleration sensor.

For analysis of MMG data, preprocessing and frequency analysis were performed. In preprocessing of 30 s of MMG data, 15 s of data from 10 s after the start of measurement were extracted for analysis. Thereafter, 15 s of MMG data were subjected to a fourth-order Butterworth bandpass filter (5–35 Hz). Next, the frequency characteristics of MMG data were analyzed by frequency analysis. Regarding the interpretation of MMG data, previous MMG related studies have suggested the effectiveness of frequency PSD39.

Here, f is the frequency, Sxx(f) is PSD based on a periodogram considering the signal length of finite time series data, x is MMG data as discrete time series data, N is the number of time series data, n is an index of time series data, e is Napier’s number, i is an imaginary unit, Δt is a sampling period, and T (=(N-1)/Δt) is a finite signal length of time series data. Note that the window size as the signal length of time-series data was 256. The unit of PSD is [(m/s2)2/Hz]. The Nyquist frequency of the MMG data was 43.6 Hz for a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor (sampling frequency: 87.2 Hz) and 45 Hz for a commercially available acceleration sensor (sampling frequency: 90 Hz).

Moreover, to further compare the characteristics of MMG data between HC and PD, an energy difference value was calculated by subtracting the energy value of the Rest condition from that of the Pinch condition. Each energy value was obtained by integrating the PSD on the frequency axis. Specifically, the energy value in the frequency ranges from fp [Hz] to fq [Hz] in muscle sound data (E[fp, fq]) is calculated using the following formula. The unit of E(fp, fq) is [(m/s2)2].

Therefore, the energy difference value in the frequency ranges from fp [Hz] to fq [Hz] of the MMG data for the Pinch condition with respect to the MMG data for the Rest condition is calculated by the following formula:

Here, \(\:{E}_{Rest}\left({f}_{p},{f}_{q}\right)\) and \(\:{E}_{Pinch}\left({f}_{p},{f}_{q}\right)\) are the energy values in the frequency interval from fp [Hz] to fq [Hz] for the Rest and Pinch conditions, respectively. For each participant, nine data samples were created by combining three MMG data for the Rest condition and three MMG data for the Pinch condition (Fig. 3a). This energy difference value was calculated based on the nine data samples in combination of MMG data in the Rest and Pinch conditions. Therefore, 90 data samples for HC MMG data (10 [HC participants] × 3 [MMG data for the Rest condition] × 3 [MMG data for the Pinch condition]) and 162 pieces data samples for PD MMG data (18 [PD participants] × 3 [MMG data for the Rest condition] × 3 [MMG data for the Pinch condition]) were used in the analysis of the energy difference value. Generally, some data samples were excluded because the frequency energy of muscle output in an exercise state is generally higher than that in a resting state. Specifically, in the 5–35 Hz frequency band, if the total frequency energy of MMG in the Rest condition was higher than that in the Pinch condition, the data sample was excluded. Hence, the number of data samples to be analyzed included 77 and 138 data samples for HC and PD MMG data, respectively.

Dataset and deep learning model. (a) Dataset in experiment for combination between mechanomyogram (MMG) data for Rest and Pinch conditions in each participant. (b) Multivariate long short-term memory-fully convolutional networks (MLSTM-FCNs) for time series classification as a representative classification model36. There are three types of datasets for inputting MLSTM-FCNs: (b1) low-MMG dataset case, (b2) micro-MMG dataset case, and (b3) low- and micro-MMG dataset case.

Method for micro-mechanomyogram-based PD classification

Data preprocess and dataset construction

We investigated the construction of an automatic classification system for PD based on MMG data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. Specifically, the following classifier dataset, classification model, and classifier evaluation method were used.

Three types of classifier datasets were prepared: micro-MMG, low-MMG, and low- and micro-MMG datasets. All datasets consisted of input and teacher data used in the training and evaluation phases of the classification of PD. The teacher data used the epidemiological data labels of the participants and was determined based on the diagnosis based on modified-HY by a PD specialist doctor. Two labels, PD and HC, were used. This teacher data were commonly used in all three datasets.

The input dataset for the micro-MMG dataset was MMG data for the Rest and Pinch conditions of PD and HC, respectively, which were measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. In data preprocessing, normalization was performed on all MMG data. Next, the 15–35 Hz frequency component corresponding to micro-MMG was extracted from the MMG data for the Rest and Pinch conditions using a fourth-order Butterworth bandpass filter. Then, a data sample was created that combined the micro-MMG data for the Rest and Pinch conditions. This data sample entailed a combination of three micro-MMG data each from the Rest and Pinch conditions for each participant (Fig. 3a). Therefore, 90 data samples of HP micro-MMG data (10 [HC participants] × 3 [micro-MMG data for the Rest condition] × 3 [micro-MMG data for the Pinch condition]) and 162 pieces of PD micro-MMG data (18 [PD participants] × 3 [micro-MMG data for the Rest condition] × 3 [micro-MMG data for the Pinch condition]) were prepared as the input data for micro-MMG dataset. Therefore, the input data for the micro-MMG dataset was a two-dimensional vector that was a combination of one-dimensional vectors of micro-MMG data for the Rest and the Pinch conditions.

The input data for the low-MMG dataset was created using the same protocol as the input data for the micro-MMG dataset, with the difference being that the 5–15 Hz frequency components corresponding to low-MMG were extracted in the process of a fourth-order Butterworth bandpass filter. Therefore, the input data for the low-MMG dataset was a two-dimensional vector that was a combination of one-dimensional vectors of low-MMG data for the Rest and Pinch conditions.

The low- and micro-MMG dataset was a combination of both the micro-MMG and low-MMG datasets. Therefore, the input data were four-dimensional vectors combining a two-dimensional vector as input data for the micro-MMG dataset and a two-dimensional vector as input data for the low-MMG dataset.

Some data samples were excluded because the frequency energy of muscle output in an exercise state is generally greater than that in a resting state. Specifically, in the frequency band of 5–35 Hz, if the total frequency energy of MMG in the Rest condition was larger than that in the Pinch condition, this data sample was excluded. Hence, the number of data samples to be analyzed included 77 and 138 data samples for HC and 13 PD MMG data, respectively. Therefore, the number of data samples included for analysis was 215 (77 + 138) data samples in total for each of the low-MMG dataset, the micro-MMG dataset, and the low- and micro-MMG dataset.

Classification model and evaluation index

We used MLSTM-FCNs for time series classification as a representative classification model36 (Fig. 3b). MLSTM-FCNs proposes that the accuracy of time-series classification problems can be improved by using an FCN and LSTM in parallel, which have shown strong results in time-series classification data problems. Indeed, the performance was previously evaluated with demonstrated high performance on time series classification problems using biological time series. Specifically, Karim et al40. evaluated long short-term memory-fully convolutional networks (LSTM-FCNs) for one-channel input of timeseries using University of California, Riverside (UCR) time series datasets41that include time series classification problem datasets. The datasets for evaluation were based on time series classification problems, including biological information-related time series Electrooculogram Horizontal Signal, Electrooculogram Vertical Signal within UCR time series datasets. The results showed that LSTM-FCNs, which integrate LSTM block and FCN block, exhibited higher performance versus models using only LSTM block and FCN block. Karim et al36. constructed MLSTM-FCNs by applying multi-channel input of timeseries to LSTM-FCNs. Hence, MLSTM-FCNs demonstrated higher performance versus LSTM-FCNs in evaluations targeting time series classification problems including biological information-related time series (electrocardiogram, electroencephalogram).

We dealt with a time series classification problem in which the input data was a time series of MMG data as biological information, and the binary categories of PD and HC were used as training data. Therefore, we determined that MLSTM-FCNs was the most appropriate classification model and used this model in the experiment. The hyperparameters of MLSTM-FCNs used in this study follow previous research36. The convolution blocks have kernel sizes of 8, 5, and 3, and parameters that include 128, 256, and 128 filters. We used the shape of the input data as “(T, C).” Here, T represents the duration and C represents the number of data channels. Specifically, T is 1308, which is the data length in 15 s of MMG data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor (1308 = 87.2 [Hz] × 15[s]). C is 2 with usage of the low-MMG dataset and the micro-MMG dataset. C is 4 with usage of the low- and micro-MMG dataset.

For the evaluation index, 5-fold cross validation based on the division of participants was used to evaluate the performance of the trained classification model42,43. There are two methods of separating training and test data in cross-validation: subject-wise and record-wise44. In this study, we adopted the subject-wise method to ensure that the training and test datasets do not contain the same individual’s information, closely resembling real-world application scenarios. Performance was evaluated using accuracy, F1-score, recall, and precision metrics.

Results

Measurement of micro-mechanomyogram and motor symptoms in PD

Micro-MMG measured using high-sensitivity acceleration sensor

Figure 4a is an example of the PSD of MMG data as acceleration data measured under a relaxed Rest condition with a sensor box attached to the extensor pollicis brevis muscle of the HC. Focusing on the PSD (blue line) of MMG data measured with a commercial acceleration sensor, a characteristic distribution is shown below 15 Hz, while it becomes flat in the region ≥ 15 Hz, which is similar to the noise floor of the commercial acceleration sensor (-70 dB/Hz). This means that commercial acceleration sensors cannot detect MMG data in a region < -70 dB/Hz, and especially MMG data in a region ≥ 15 Hz which is hidden below the noise floor. Alternatively, when focusing on the PSD (orange line) of MMG data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, a characteristic distribution below 15 Hz is shown, similar to that of commercial acceleration sensors. Surprisingly, in the region above 15 Hz, a characteristic shape of the frequency distribution can be seen in the region with a PSD level even < -70 dB/Hz. This indicates that MMG in the region of ≥ 15 Hz was not measured by commercial acceleration sensors, only by high-sensitivity acceleration sensors.

Example of the frequency power spectral density of mechanomyogram data as acceleration data measured by commercial acceleration sensor and high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. (a) Age-matched healthy controls (HC) in the Rest condition. (b) Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in the Rest condition. (c) HC in the Pinch condition. (d) Patients with PD in the Pinch condition. MMG, mechanomyogram.

The frequency characteristics of MMG data detected in the frequency range ≥ 15 Hz are micro-vibration components of MMG that were first measured by measuring muscle sound data using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. Therefore, we defined MMG with high-frequency components of ≥ 15 Hz as “micro-MMG”, in contrast to MMG with low frequency components of < 15 Hz as “low-MMG,” which can be measured conventionally. Surprisingly, micro-MMG were not only detected in the MMG data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor under the Rest condition in which the extensor pollicis brevis of the HC is relaxed (Fig. 4a), but also detected under the Pinch condition with muscle output from the extensor digitorum muscle (Fig. 4b). Moreover, in HC and in PwPD, by using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor in the extensor pollicis brevis muscle under the Rest condition (Fig. 4c) and Pinch condition (Fig. 4d), micro-MMG were detected in the area below the noise floor (-70 dB/Hz) of a commercial acceleration sensor. Therefore, in both HC and PwPD, the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor detected MMG frequency characteristics < the noise floor (-70 dB/Hz) of commercial acceleration sensors, indicating that investigating whether micro-MMGs contain information about PD is possible by separating and analyzing MMG data measured with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor into low-frequency MMG below 15 Hz (low-MMG), which were previously detected, and MMG above 15 Hz (micro-MMG).

Comparison of MMG frequency PSD distribution between PD and HC

We investigated whether micro-MMG contained information about PD. Specifically, the average PSD of MMG data was calculated, and the Rest and Pinch conditions were compared separately for HC (Fig. 5a) and PwPD (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the characteristics of the average PSD in the Rest and Pinch conditions differed between HC (Fig. 5a) and PwPD (Fig. 5b). In the average PSD of MMG data, for HC (Fig. 5a), there was a small change in the increase in PSD in the Pinch versus Rest conditions in low-MMG below 15 Hz. In contrast, there was a large increase in the PSD value in the Pinch versus Rest conditions for micro-MMG of ≥ 15 Hz. Alternatively, in PwPD (Fig. 5b), unlike HC (Fig. 5a), there was a large change in the increase in PSD in the Pinch versus Rest conditions in low-MMG below 15 Hz. In contrast, there was a small increase in the PSD value in the Pinch versus Rest conditions for micro-MMG of ≥ 15 Hz.

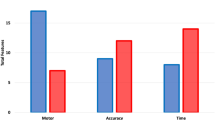

Average frequency power spectral density of mechanomyogram data as acceleration data measured by high-sensitivity acceleration sensor in age-matched HC and patients with PD, differential energy value analysis result, and classification performance between PD and HC based on MMG. (a) Average PSD in HC. (b) Average PSD in patients with PD. (c) Differential energy value of Pinch condition relative to Rest condition in MMG. (d) Classification performance in accuracy by using low-MMG dataset, micro-MMG dataset, and low- and micro-MMG dataset, respectively. HC, healthy controls; MMG, mechanomyogram; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PSD, power spectral density.

These results indicate that different HC and PD characteristics were detected in low-MMG and micro-MMG, respectively, suggesting that the signal sources for low-MMG and micro-MMG differ. The low-MMG frequency band below 15 Hz corresponds to the frequency band of hand tremors based on motor symptoms in PwPD45,46. Therefore, micro-MMG is considered a new information source, different from hand tremors caused by PD motor disorders. The relationship between low-MMG, which is based on hand tremor information, and micro-MMG, which is a new source of information regarding PD motor symptoms, may provide important information for the diagnosis of PD. Therefore, micro-MMG may be used as a different information source that contributes to the classification of HC and PwPD.

Statistical analysis for comparing MMG frequency energy characteristic between PD and HC

Furthermore, we investigated whether micro-MMG and low-MMG (hand tremors) are related to PD. Figure 5c; Table 1 present the results of the comparison of energy difference values for MMG data between HC and PwPD in both the low-MMG below 15 Hz and micro-MMG above 15 Hz. The energy difference value is calculated by subtracting the energy value of the Rest condition from that of the Pinch condition. Note that the energy value was obtained by integrating the PSD of MMG data by frequency. The results of a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance revealed a significant interaction (F = 10.88, p < 0.01). There was also a was significant main effect of {HC, PD} (F = 4.83, p < 0.05), and of {Low-MMG, Micro-MMG} (F = 84.28, p < 0.001). A subtest using multiple comparisons based on Shaffer’s method revealed a significant difference in the energy difference value in low-MMG between HC (8.89 [± 7.23]×10−6[(m/s2)2]) and PD (15.48 [± 20.21]×10−6[(m/s2)2]) (p < 0.01). A significant difference also was observed in the energy difference value in micro-MMG between HC (1.96 [± 2.40]×10−6[(m/s2)2]) and PD (0.78 [± 1.00]×10−6[(m/s2)2]) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant difference was observed in the energy difference value of HC between low-MMG and micro-MMG (p < 0.001). Similarly, a significant difference was observed in the energy difference value of PD between low-MMG and micro-MMG (p < 0.001), indicating that low-MMG, which is based on hand tremor information, and micro-MMG, which is a new information source regarding PD motor symptoms, have different characteristics between HC and PwPD, suggesting that the unique information of low-MMG and micro-MMG are different information sources for classifying PwPD from HC.

Classification of PD based on micro-MMG and motor symptoms

From the viewpoint of the statistical analysis results for comparing MMG frequency energy characteristic between PD and HC, it was suggested that the unique information of low-MMG, which was based on hand tremor information, and micro-MMG, which was a new information source regarding PD motor symptoms, were different information sources for classifying PwPD from HC. Accuracy and F1-score were used to evaluate PD classification performance. Furthermore, recall and precision, which are important in clinical application, were used for evaluation.

Accuracy, F1-score, recall, and precision as evaluation results are shown in Fig. 5d; Table 2. When the low-MMG dataset was used, the accuracy and F1-score of PD classification results were 87.08% and 86.46%, respectively. Alternatively, when the micro-MMG dataset was used, the accuracy and F1-score of the PD classification results were 82.42% and 81.65%, respectively. Surprisingly, when a low- and micro-MMG dataset combining both low-MMG and micro-MMG was used, the accuracy and F1-score of the PD classification results were 92.19% and 91.92%, respectively. Therefore, by utilizing MMG data that includes micro-MMG in addition to the conventionally measurable low-MMG, maximum performance in PD classification was achieved.

Recall and precision, which are important, in especially clinical evaluation, were also evaluated. Recall is a classifier’s ability to find all truthful cases in a class. Precision evaluates a classifier’s ability to identify only the truthful cases for each class. When the low-MMG dataset was used, the recall and precision of PD classification results were 85.08% and 88.13%, respectively. Alternatively, when the micro-MMG dataset was used, the recall and precision of the PD classification results were 77.07% and 87.41%, respectively. Surprisingly, when a low- and micro-MMG dataset combining both low-MMG and micro-MMG was used, the recall and precision of the PD classification results were 91.38% and 92.55%, respectively. Therefore, the results suggest that the use of MMG data that includes micro-MMG in addition to the conventionally measurable low-MMG leads to high performance in tests to identify symptoms of PD.

Discussion

We aimed to achieve diagnosis using both motor symptoms and micro-MMG in PwPD as information sources regarding signs of PD. Accordingly, we first analyzed the relationship between micro-MMG and PD motor symptoms and investigated the effectiveness of micro-MMG as an information source. We then investigated the realization of a PD classification system by using micro-MMG and motor symptoms as information sources. Therefore, we built a PD classification system with the deep learning model of MLSTM-FCNs for PD diagnosis assistance by using low-MMG and micro-MMG as information sources.

We are the first to measure micro-MMG in PwPD using a highly sensitive acceleration sensor developed by our research group. By using a mass made of gold material, this high-sensitivity acceleration sensor has a noise floor that is approximately 10 dB lower than conventionally used commercial acceleration sensors and can measure vibrations as acceleration data with higher sensitivity21. Previously, MMG data were measured in a young, healthy individual by attaching a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor to the skin near the extensor pollicis brevis muscle located at the base of the thumb. The possibility of measuring MMG data with high sensitivity was demonstrated. In contrast, this study succeeded in measuring micro-MMG in PwPD for the first time.

By attaching a highly sensitive acceleration sensor to the extensor pollicis brevis muscle of the fingers of PwPD and age-matched HC, this sensor detected the following two types of information. The first is the vibration component of low-MMG, which is MMG data in the 5–15 Hz frequency band, which can be measured with commercially available acceleration sensors. This MMG data below 15 Hz corresponds to the frequency band of hand vibrations based on motor symptoms in PwPD47. The second is the micro-vibration component of MMG data in the high-frequency band of ≥ 15 Hz, which can be measured for the first time using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. In contrast to the former low-MMG, this study defined the micro-vibration components in the high-frequency band of MMG as “micro-MMG.” Therefore, micro-MMG, which is the micro-vibration region of MMG that cannot be detected with commercial acceleration sensors, can now be detected with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. This means that high-sensitivity acceleration sensors can simultaneously measure hand vibrations as low-MMG, which are motor symptoms in PwPD, and micro-MMG as new information source to identify symptoms of PD.

Additionally, we analyzed the characteristics of both motor symptoms and micro-MMG in PwPD and HC and elucidated their effectiveness as information sources. A high-sensitivity acceleration sensor was placed on the skin near the extensor pollicis brevis muscle located at the base of the thumb. MMG data was measured under the Rest condition, which is a relaxed state with no muscle output, and the Pinch condition, which involves muscle output. The analysis results of the frequency characteristics of MMG using PSD, the characteristics of MMG data differed between HC and PwPD. Specifically, the differences in the characteristics of low-MMG and micro-MMG between HC and PwPD were compared in the analysis of frequency energy difference values. In low-MMG, which is related to hand vibration motor symptoms with PD, the energy difference value between the Pinch and Rest conditions in PwPD was significantly larger than that in HC, suggesting that when muscle output occurs to the extensor pollicis brevis muscle, the energy of the vibration component associated with the hand vibration due to motor symptoms increases in PwPD versus HC. Alternatively, for micro-MMG, the energy difference value between the PD Rest and Pinch conditions was significantly smaller versus HC. Therefore, these findings suggest that when muscle output occurs to the extensor pollicis brevis muscle, the energy of the vibration component related to micro-MMG is reduced in PwPD than in HC.

These results suggest that the signal sources of low-MMG and micro-MMG, which are associated with hand tremors in motor symptoms, differ. Measuring MMG data with a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor means that information from two different signal sources can be used simultaneously. This indicates the possibility that both low-MMG and micro-MMG, which can be measured simultaneously using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, can be used as different information sources that contribute to the classification of HC and PwPD. The possibility of measuring MMG in healthy, young individuals using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor has already been demonstrated in case studies21. However, there has been no report that provides not only information on visible motor symptoms, such as impaired postural reflexes and tremors, but also information on micro-MMG simultaneously observed for the diagnosis of PD. The evidence from this study suggests the possibility of simultaneously measuring motor symptoms and micro-MMG. Using both motor symptoms and micro-MMG as information sources contributes to ultra-accurate classification of PwPD.

Currently, there are no reports on the physiological mechanisms of micro-MMG as MMG in the high-frequency band above 15 Hz. Therefore, further investigation from this perspective and elucidation of these mechanisms are expected in the future. However, as a supplementary consideration, we reviewed findings from previous research on electromyography (EMG) as an electrophysiological phenomenon related to MMG. A previous electro-physiological study48 simultaneously measured peripheral EMG of the upper extremities and basal ganglia electrical activity via deep brain electrodes in PwPD, analyzing the relationship between these two bioelectrical signals. Specifically, simultaneous recordings of local field potentials in the subthalamic nucleus and wrist EMG were obtained in PwPD. The effects of dopaminergic status and exercise on long-range beta functional connections between the basal ganglia and lower motor neurons were then investigated. The results showed long-range coherence in specific frequency regions, suggesting a functional coupling between deep brain and peripheral muscle activities. Such findings from previous research on the electrical aspects of muscle fibers may be important in elucidating the neuro-scientific mechanism of micro-MMG as tiny mechanical vibrations of muscle fibers.

Moreover, this study succeeded in constructing a system that can automatically classify PwPD and HC with high accuracy using both low-MMG and micro-MMG information related to hand tremors due to motor symptoms. Specifically, by using MLSTM-FCNs, a representative deep learning model, we achieved a classification accuracy of 92.19% for PwPD by using both low-MMG and micro-MMG signals as information sources. This is the highest classification accuracy measured by a single acceleration sensor. Previous studies have developed a classification system for PwPD using only hand vibrations as low-MMG34,35. Specifically, two IMU sensors were used: one worn on the wrist and the other on the middle finger. Acceleration data in the hand tremor frequency range was used in a machine learning or deep learning model to classify PD with an accuracy of approximately 85%. In contrast, we showed that using MMG data measured by a single high-sensitivity acceleration sensor achieved performance > 85%. This method can be realized only by measurements based on this small-sized highly sensitive acceleration sensor and is considered effective in clinical applications since it places a lesser burden on PwPD. This suggests the effectiveness of micro-MMG as a micro-vibration component in the high-frequency band of MMG data in an automatic PD classification system. This novel finding may lead to the development of an ultra-early detection system for PD. Furthermore, this study marks the first worldwide to measure high-frequency micro-vibrations of muscle fibers, referred to as micro-MMG, in PwPD using the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. Independently developed by our research group, this sensor can detect vibrations that are more than 10 dB smaller than those detected by conventional commercial sensors21,22. The findings indicate that a new frontier in detecting information carriers of new biological conditions using the high-sensitivity acceleration sensor has been opened.

Limitations

This research has some limitations. First, we classified PwPD and age-matched HC with the highest classification accuracy to date. However, as a further challenge, we intend to take on more difficult tasks, including applying our findings to the classification of mild PD and HC and the process of PD onset. Second, we clarified that low-MMG, caused by hand vibrations caused by motor symptoms in PwPD, and micro-MMG, which are micro-vibration components in the high-frequency band of MMG data, are different signal sources. However, the mechanism by which this occurs has not been clarified in this study, and future studies should elucidate the mechanism by which micro-MMG is generated. Third, in this study, statistically significant differences were observed in the data from a given number of experimental participants. Further verification with a larger set of data will be important in reconfirming and further developing the results of this study. Fourth, since the scale of clinical data collection from PwPD is limited, further utilization of data augmentation in deep learning techniques is another challenge for future studies.

Conclusion

The high-sensitivity acceleration sensors independently developed by our research group are capable of detecting vibrations that are more than 10 dB smaller than those detected by conventional commercial sensors. This study is the first worldwide to measure high-frequency micro-vibrations of muscle fibers, referred to as micro-MMG, in PwPD using a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor. In conclusion, this study represents a significant advancement in comprehending the intricacies of body vibration characteristics in PwPD. The introduction of a high-sensitivity acceleration sensor, surpassing the capabilities of existing commercial sensors, has enabled the identification of micro-MMG in the extensor pollicis brevis muscle of PwPD, previously imperceptible through conventional acceleration sensors. Our findings unveil pronounced distinctions in the frequency characteristics of micro-MMG between PwPD and HC. Specifically, during muscle power output in the extensor pollicis brevis muscle, PwPD exhibited a marked increase in low-frequency-MMG energy, contrasting with the patterns observed in HC. Simultaneously, the high-frequency-MMG in PwPD was notably diminished compared with HC. Of particular significance is the successful application of a deep learning model trained on micro-MMG data. This model demonstrated a remarkable classification accuracy of 92.19%, providing compelling evidence for its potential integration into practical PD diagnosis assistive systems. This breakthrough enhances our understanding of PD and opens avenues to develop a PD diagnosis system specifically tailored to micro-MMG patterns, a promising frontier in the realm of neurodegenerative disease research. The implications of this research extend beyond this study, contributing valuable insights to the broader scientific community and paving the way for innovative diagnostic tools and strategies. In the future, we expect that the range of applications of the technology for detecting information carriers of new biological conditions using the sensor we developed will be expanded. Furthermore, it is expected that micro-MMG will be applied in new applications that provide ultra-early detection of PD.

Data availability

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

21 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15060-2

References

Laine, J. & Mougenot, D. Benefits of MEMS Based Seismic Accelerometers for Oil Exploration. TRANSDUCERS 2007–2007 International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference, 1473–1477 (2007).

Shaeffer, D. K. MEMS inertial sensors: a tutorial overview. IEEE Commun. Mag. 51, 100–109 (2013). (DOI 10.1109/MCOM.2013.6495768).

Scudero, S., D’Alessandro, A., Greco, L. & Vitale, G. MEMS technology in seismology: A short review. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Environmental Engineering, 1–5 (2018) (DOI (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/EE1.2018.8385252).

Krishnan, G., Kshirsagar, C. U., Ananthasuresh, G. K. & Bhat, N. Micromachined high-resolution accelerometers. J. Indian Inst. Sci.87, 333–361 (2007).

Boser, B. E. & Howe, R. T. Surface micromachined accelerometers. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 31, 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1109/4.494198) (1996).

Lemkin, M. & Boser, B. E. A three-axis micromachined accelerometer with a CMOS position-sense interface and digital offset-trim electronics. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 34, 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1109/4.753678) (1999).

Wu, J., Fedder, G. K. & Carley, L. R. A low-noise low-offset capacitive sensing amplifier for a 50-/spl mu/g//spl radic/Hz monolithic CMOS MEMS accelerometer. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits. 39, 722–730 (2004).

Amini, B. V. & Ayazi, F. Micro-gravity capacitive silicon-on-insulator accelerometers. J. Micromech Microeng. 15, 2113–2120. https://doi.org/10.1088/0960-1317/15/11/017) (2005).

Kulah, H., Chae, J., Yazdi, N. & Najafi, K. Noise analysis and characterization of a sigma-delta capacitive microaccelerometer. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 41, 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2005.863148) (2006).

Abdolvand, R., Amini, B. V. & Ayazi, F. Sub-micro-gravity in-plane accelerometers with reduced capacitive gaps and extra seismic mass. J. Microelectromech Syst.16, 1036–1043. https://doi.org/10.1109/JMEMS.2007.900879) (2007).

Qu, H., Fang, D. & Xie, H. A monolithic CMOS-MEMS 3-axis accelerometer with a low-noise, low-power dual-chopper amplifier. IEEE Sens. J.8, 1511–1518. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2008.923582) (2008).

Dong, Y., Zwahlen, P., Nguyen, A. M., Rudolf, F. & Stauffer, J. M. High performance inertial navigation grade sigma-delta MEMS accelerometer. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/PLANS.2010.5507135 (2010). Location and Navigation Symposium.

Tan, S. S. et al. An integrated low-noise sensing circuit with efficient bias stabilization for CMOS MEMS capacitive accelerometers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I. 58, 2661–2672. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2011.2142990) (2011).

Homeijer, B. et al. Hewlett Packard’s seismic grade MEMS accelerometer (IEEE, 20112011) 24th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2011.5734492).

Tsai, M. H., Liu, Y. C., Liang, K. C. & Fang, W. Monolithic CMOS–MEMS pure oxide tri-axis accelerometers for temperature stabilization and performance enhancement. J. Microelectromech Syst.24, 1916–1927. https://doi.org/10.1109/JMEMS.2015.2452270) (2015).

Zhu, W., Zhang, Y., Meng, G., Wallace, C. S. & Yazdi, N. A CMOS-integrated four-quadrant symmetric micro-g accelerometer (IEEE, 20162016) 29th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) (https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2016.7421783).

Machida, K. et al. A novel semiconductor capacitive sensor for a single-chip fingerprint sensor/identifier LSI. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 48, 2273–2278. https://doi.org/10.1109/16.954466) (2001).

Yamane, D. et al. APCOT. A novel mems inertial sensor with out-of-plane differential sensing structure by multi-layer metal technology. Asia and the Pacific Conference of Transducers and Micro-NanoTechnology 299, 2016 (2016).

Yamane, D. et al. Design of sub-1 g microelectromechanical systems accelerometers. Appl. Phys. Lett.104https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4865377) (2014).

Konishi, T. et al. Novel sensor structure and its evaluation for integrated complementary metal oxide semiconductor microelectromechanical systems accelerometer. Jpn J. Appl. Phys.52https://doi.org/10.7567/JJAP.52.06GL04) (2013).

Onishi, A. et al. Suppressed drift and low-noise sensor module with a single-axis gold proof-mass MEMS accelerometer for micro muscle sound measurement. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 61, SD1028. https://doi.org/10.35848/1347-4065/ac5b25 (2022).

Koga, T. et al. High-sensitivity inertial sensor module to measure hidden micro muscular sounds. Proceedings of the of the 2019 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Nara, Japan, Oct 17–19, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/BIOCAS.2019.8919151.

Watakabe, M., Mita, K., Akataki, K. & Ito, K. Reliability of the mechanomyogram detected with an accelerometer during voluntary contractions. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput.41, 198–202 (2003). (DOI 10.1007/BF02344888) (Pubmed:12691440).

Dorsey, E. R. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Neurol.17, 939–953 (2018).

Balestrino, R. & Schapira, A. H. V. Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Neurol.27, 27–42 (2020). (DOI 10.1111/ene.14108) (Pubmed:31631455).

De Rijk, M. C. et al. A population perspective on diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 48, 1277–1281. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.48.5.1277) (1997). (Pubmed:9153457).

Armstrong, M. J. & Okun, M. S. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA. 323, 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.22360) (2020). (Pubmed:32044947).

Tolosa, E., Wenning, G. & Poewe, W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol.5, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70285-4) (2006). (Pubmed:16361025).

Rajput, A. H., Rozdilsky, B. & Rajput, A. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis in parkinsonism—a prospective study. Can. J. Neurol. Sci.18, 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0317167100031814) (1991). (Pubmed:1913360).

Poewe, W. et al. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.13) (2017).

Hoehn, M. M. & Yahr, M. D. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 17, 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.17.5.427) (1967). (Pubmed:6067254).

Goetz, C. G. et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 19, 1020–1028 (2004). (DOI 10.1002/mds.20213) (Pubmed:15372591).

Jeon, H. et al. Automatic classification of tremor severity in Parkinson’s disease using a wearable device. Sensors (Basel) 17, (2017) (DOI (2067). https://doi.org/10.3390/s17092067) (Pubmed:28891942).

Jeon, H. et al. High-accuracy automatic classification of parkinsonian tremor severity using machine learning method. Physiol. Meas.38, 1980–1999. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6579/aa8e1f) (2017). (Pubmed:28933707).

Kim, H. B. et al. Wrist sensor-based tremor severity quantification in Parkinson’s disease using convolutional neural network. Comput. Biol. Med.95, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.02.007) (2018). (Pubmed:29500984).

Karim, F., Majumdar, S., Darabi, H. & Harford, S. Multivariate LSTM-FCNs for time series classification. Neural Netw.116, 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2019.04.014) (2019). (Pubmed:31121421).

Yamane, D. et al. Asia and the Pacific Conference of Transducers and Micro-NanoTechnology, 2016. Kanazawa, Japan. June 26–29 299.

InvenSense Inc. MPU-6000 and MPU-6050 product specification, document number: PS-MPU-6000A-00. Revision: 3.4. https://invensense.tdk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/MPU-6000-Datasheet1.pdf (InvenSense Inc., 2013).

Ibitoye, M. O., Hamzaid, N. A. & Zuniga, J. M. Abdul Wahab, A. K. A. Mechanomyography and muscle function assessment: a review of current state and prospects. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol Avon). 29, 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.04.003) (2014). (Pubmed:24856875).

Karim, F., Somshubra, M. R. & Houshang, D. Insights into LSTM fully convolutional networks for time series classification. Preprint at.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1902.10756 (2019).

Dau, H. A. et al. The UCR Time Series Classification Archive (2018). https://www.cs.ucr.edu/~eamonn/time_series_data_2018/

Kuhn, M. & Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling13 (Springer, 2013).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning 1st edn (Springer, 2013).

Tougui, I., Jilbab, A. & El Mhamdi, J. E. Impact of the choice of cross-validation techniques on the results of machine learning-based diagnostic applications. Healthc. Inf. Res.27, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2021.27.3.189) (2021). (Pubmed:34384201).

Prochazka, A. & Trend, P. S. Instability in human forearm movements studied with feed-back-controlled muscle vibration. J. Physiol.402, 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017213) (1988). (Pubmed:2976825).

Brown, T. I., Rack, P. M. & Ross, H. F. Different types of tremor in the human thumb. J. Physiol.332, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014404) (1982). (Pubmed:7153923).

Marusiak, J., Jaskólska, A., Kisiel-Sajewicz, K., Yue, G. H. & Jaskólski, A. EMG and MMG activities of agonist and antagonist muscles in Parkinson’s disease patients during absolute submaximal load holding. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.19, 903–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.03.003) (2009). (Pubmed:18456512).

Ramirez Pasos, U. E. et al. Levodopa modulates functional connectivity in the upper beta band between subthalamic nucleus and muscle activity in tonic and phasic motor activity patterns in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci.13, 223. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00223) (2019). (Pubmed:31312129).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST CREST [Grant Number JPMJCR21C5], JST COI-NEXT [Grant Number JPMJPF2101], JSPS KAKENHI [Grant Number 22K17630], and JST SPRING [Grant Number JPMJSP2106].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JQ, HU, RS, CG, TO, and YM contributed to the study conception and design. RS, TO, HI, KM, MS, and YM developed and implemented the experimental systems. RS, TO and SO conducted the experiment. JQ, HU, RS, CG, TO, and YM performed feature analysis and statistical analysis. JQ, HU, and YM built a deep learning model and evaluated its performance. All authors discussed and interpreted the results. JQ and HU drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The title, author byline, and contributions section were changed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quan, J., Uchitomi, H., Shigeyama, R. et al. Application of high-sensitivity acceleration sensor detecting micro-mechanomyogram and deep learning for Parkinson’s disease classification. Sci Rep 14, 22941 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74526-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74526-x